Abstract

Increased fibronectin (FN) expression has an important role during liver fibrosis. The present study examined FN expression in rats subjected to carbon tetrachloride (CCl4)-induced liver fibrosis. In addition, the potential mechanisms underlying fibrogenesis were investigated by exposing hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) to transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), which is a known inducer of myofibroblastic transformation of HSCs. Briefly, a rat model of liver fibrosis was created by administering intraperitoneal injections of CCl4. Furthermore, HSC-T6 cells were stimulated with increasing doses of recombinant TGF-β over 24 h. Hepatic fibrosis gradually increased following CCl4 administration in vivo. Western blotting and immunohistochemistry demonstrated that fibronectin (FN), TGF-β and α-smooth muscle actin (SMA) expression was increased following CCl4 injection, and the maximum expression levels were observed at 8 weeks. Once CCl4 treatment had been terminated, the expression levels of FN, TGF-β and α-SMA progressively declined to near baseline levels. Western blotting and quantitative polymerase chain reaction demonstrated that FN expression was gradually increased in response to TGF-β-stimulation of HSCs; maximum expression was achieved 12 h post-treatment (P<0.01 vs. the baseline). In conclusion, these findings indicated that FN expression is an early and progressive event that occurs during liver fibrogenesis in vivo and in vitro.

Keywords: fibronectin, liver fibrosis, myofibroblast, transforming growth factor-β

Introduction

Liver fibrosis results from dysregulation of the normal healing process and scar formation, and is a common and potentially severe consequence of virtually all chronic liver diseases (1). Diseases that may lead to liver fibrosis include: Viral and autoimmune hepatitis, drug injury, iron deposition, alcohol consumption and biliary obstruction.

Fibronectin (FN), which is produced by hepatic stellate cells (HSCs), is a multifunctional glycoprotein and extracellular matrix (ECM) component that is present in the cell membrane and cytoplasm (2,3). FN is required in vitro for collagen matrix assembly, and can be used to support other matrix proteins (4–6). In addition, FN is associated with cell cycle progression, participates in cell adhesion and proliferation, and has an important role in fibrotic progression (7). Although collagen is the main ECM component of fibrotic tissue, excessive FN deposition occurs prior to collagen deposition. Increased expression of the FN isoforms EIIIA and EIIIB occurs during wound healing and tissue repair. These tissue-remodeling processes are associated with liver fibrogenesis, and the expression of these isoforms is often considered an important indicator of ECM accumulation (8–10). Kawelke et al (11) reported that FN protects against excessive liver fibrosis by modulating stellate cell availability and the responsiveness of stellate cells to active transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β). In addition, Kawelke et al (11) demonstrated that loss of FN expression leads to increased stellate cell activation at baseline and following TGF-β stimulation. Altrock et al (12) reported that interference in collagen deposition, via FN matrix formation inhibitors, decreased fibrosis and improved liver function.

Since FN appears to have an important role in liver fibrogenesis, FN expression may be considered a critical factor mediating the long-term consequences of several chronic liver diseases. Therefore, the present study aimed to determine FN expression patterns during hepatic fibrogenesis using in vitro and in vivo models. The former was conducted with HSCs, which were stimulated with TGF-β, and the process of fibrogenesis of these cells mimicked acute hepatitis; the latter model was the CCl4 rat model, used to mimic the process of chronic liver injury, such as chronic hepatitis.

Materials and methods

Animals

A total of 50 healthy male Wistar rats (age, 6–8 weeks; weight, 180–200 g) were obtained from the Laboratory Animal Center of the Academy of Military Medical Sciences (Beijing, China). The rats were housed in a temperature- and humidity-controlled facility under a 12 h light-dark cycle, and were given ad libitum access to a standard laboratory diet and tap water. The experimental procedures and ethical requirements of the present study conformed to the Laboratory Animal Management Regulations of the People's Republic of China. All experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Experimental Committee of Beijing Friendship Hospital affiliated with Capital Medical University (Beijing, China).

Carbon tetrachloride (CCl4)-induced liver fibrosis rat model and sample collection

The 50 rats were randomly divided into the normal control group (n=6) and the liver fibrosis model group (n=44). The liver fibrosis model group received intraperitoneal injections of 0.15 ml/100 g 50% CCl4 in olive oil (5:5, v/v) twice weekly for eight weeks. Rats in the normal control group received intraperitoneal injections of the same volume of physiological saline over the same period. Reversal of liver fibrosis was investigated for 4 weeks after the final intraperitoneal injection. Rats were sacrificed at 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 and 12 weeks. Seven rats were sacrificed at each time point. Two rats succumbed without investigator intervention during week 12. All rats from the normal group were sacrificed during week 8.

All rats were euthanized under anesthesia using 1% sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg, i.p). Blood samples were collected for liver function tests. In addition, liver specimens were collected, divided into three parts and subjected to the following analyses: i) mRNA extraction using TRIzol for reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) analyses; ii) protein expression analysis of fibrotic indices using western blotting; and iii) histological and immunohistochemical analyses.

Cell culture

The HSC-T6 immortalized rat cell line (Tumor Cell Bank of Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Beijing, China) was cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), 100 IU/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin (Beijing Suolaibao Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). Cells were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. All experiments were carried out 24 h after the cells were seeded.

Cells were divided into two groups: The control group and the transforming growth factor (TGF)-β group. Recombinant human TGF-β (Sigma -Aldrich; Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany) was used, since it is a major fibrogenic mediator in the liver (13,14). TGF-β was administered to the cultured cells at 0, 1, 2, 5, 10 and 20 ng/ml for 0, 1, 3, 6, 12, 24 and 48 h. Cells were exposed to starvation conditions using FBS-free medium for 24 h prior to treatment with recombinant human TGF-β.

FN immunofluorescence assay

Cells were plated at a density of 3×105 cells/well in six-well plates, and were allowed to adhere overnight. The cells were then cultured in serum-free medium for an additional 24 h at 37°C. Subsequently, cells were rinsed in phosphate-buffered saline (3×10 min), and were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (40 min, 37°C) and 3% H2O2 (30 min, 37°C). Following fixation, cells were blocked with 1% FBS (40 min, 37°C) and were incubated overnight at 4°C with rabbit anti-mouse elastin primary antibody (FN; 1:100; sc-9068; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas, TX, USA). Goat anti-rabbit fluorescein isothiocyanate probes (1:200; bs-0295G-FITC; BIOSS, Beijing, China) were used as secondary antibodies at 37°C for 1 h. The cell nuclei were stained using 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.). Immunofluorescence was analyzed using a fluorescence microscope. Cells incubated with normal rabbit serum instead of the primary antibody served as a negative control.

Liver function test

Blood samples were centrifuged at 1,200 × g for 5 min at 4°C to separate serum from the blood. Serum aspartate transaminase (AST) and alanine transaminase (ALT) (15) activities were determined by the Clinical Laboratory (Beijing Friendship Hospital, Beijing, China).

RNA extraction and RT-qPCR

Total RNA was extracted from frozen liver samples or cultured cells using TRIzol® (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocol. RT was performed using random primers, Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus Reverse Transcriptase and RNase inhibitor (Fermentas; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The expression levels of all transcripts were normalized to the expression of the housekeeping gene, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), in the same sample. PCR was performed using Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and an ABI 7500 platform (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). RNase-free DNase (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA) was used to eliminate the contamination of genomic DNA. The first cDNA strand was synthesized by the RT reaction in a reaction mixture of 20 µl containing 4 µl MgCl2, 3 µl 10X RT buffer, 2 µl dNTP mixture, 0.5 µl recombinant RNase inhibitor, 0.6 µl AMV reverse transcriptase, 1 µl oligo dT-Adaptor primer and 5 µg RNA sample. The RT reaction product was then used for the amplification of cDNA with the SYBR Master Mix reaction system (total, 10 µl) including 1 µl upstream primers, 1 µl downstream primers, 1 µl cDNA and 7 µl diethylpyrocarbonate-treated water. PCR was conducted as follows: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 min, 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 sec and 64°C for 30 sec, followed by 95°C for 15 sec, 60°C for 1 min, 95°C for 15 sec and a final extension step at 60°C for 15 sec. Data were analyzed according to the 2−ΔΔCq method, as described by Livak and Schmittgen (16). The following primer pairs were used: FN, forward 5′-CCAGCCTACGGATGACTC-3′, reverse 5′-AATGACCACTGCCAAAGC-3′; and GAPDH, forward 5′-GGCACAGTCAAGGCTGAGAATG-3′, and reverse 5′-ATGGTGGTGAAGACGCCAGTA-3′ [Sangon Biotech (Shanghai) Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China].

Western blot analysis

Liver tissues and cultured HSCs were homogenized in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer and were centrifuged as previously described (17). The supernatants were considered whole-cell lysates. Total protein concentration was determined using a Bicinchoninc Acid Protein Assay kit (Pierce; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Proteins (~80 µg) were separated by 8% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and were transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes by electroblotting. Subsequently, the membranes were incubated for 3 h with 5% non-fat dry milk at 37°C, followed by an overnight incubation at 4°C with mouse anti-FN polyclonal antibody (1:600; sc-8422; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), rabbit anti-TGF-β antibody (1:800; ab92486; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), rabbit anti-α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) antibody (1:800; ab5694; Abcam) and mouse anti-β-actin monoclonal antibody (1:800; ab8226; Abcam). Following the overnight incubation, membranes were incubated for 1 h at 37°C with peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibodies (1:6,000 in Tris-buffered saline containing 1% Tween; sc-2005; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.). Enhanced chemiluminescence (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) was used to detect immunoreactive bands. Finally, densitometric analysis of the bands was performed using Image Lab software, version 4.0 (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA).

Histopathology and immunohistochemistry

Liver samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin and sectioned at 3 µm. The tissue sections were then stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) or Masson's trichrome, and were examined for changes in liver pathology. The histopathological scores for fibrosis were evaluated according to previously published criteria (18), as follows: 0, Normal liver; 1, increased collagen matrix accumulation without septa formation (small stellate expansions of the portal fields); 2, formation of incomplete septa from the portal tract to the central vein (septa that do not interconnect with each other); 3, complete but thin septa interconnecting with each other to divide the parenchyma into separate fragments; and 4, similar to grade 3, except for the presence of thick septa (complete cirrhosis).

Immunohistochemical analysis of paraffin-embedded sections was performed using a microwave-based antigen retrieval method, as described previously (19), and antibodies against FN were used (mouse polyclonal; 1:100; sc-8422; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.). In brief, histological sections were heated for 60 min at 60°C, deparaffinized with xylene and rinsed in a reducing gradient of alcohol. Subsequently, antigens were retrieved with citrate buffer in a microwave oven. Subsequent to treatment with hydrogen peroxide at 37°C for 30 min to block endogenous peroxidase activity, the sections were incubated with the primary antibody overnight at 4°C and then incubated with the secondary antibody (PV-9002; OriGene Technologies, Inc., Beijing, China) for 30 min at room temperature. Finally stained sections were developed using diaminobenzidine and were counterstained with hematoxylin and a BX43 optical microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) was used for analysis. FN expression was analyzed using a quantitative image analysis system (Image-Pro Plus 6.0; Media Cybernetics Inc., Rockville, MD, USA). Briefly, 10 fields were randomly selected from each section and positive signals within the section were highlighted, measured and expressed as a percentage of the positive areas within the entirety of the examined liver tissue.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were performed using SPSS software (SPSS version 17.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), and the differences between multiple groups were evaluated using one-way analysis of variance and the least significant difference test was used for multiple comparisons. Results are presented as the mean ± standard deviation and experiments were repeated 6 times. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Liver pathology in CCl4-treated mice

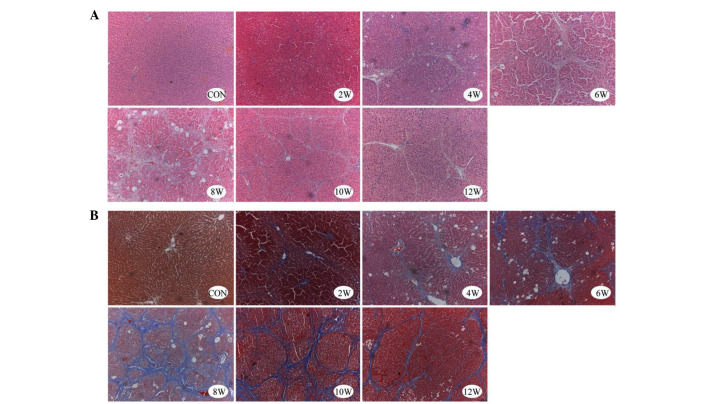

In the liver samples of the control group, normal lobular architecture was observed with hepatic cords radiating from the central veins, and the absence of regenerated collagen fibers, as detected by H&E and Masson's trichrome staining. Conversely, liver samples from the experimental group (2–12 weeks) exhibited severe fibrosis. Morphological alterations in the experimental group included thick fibrotic septa, fatty degeneration, enlarged hepatocytes with nodular arrangement, focal inflammatory changes, thickened vessel walls and early capillarization (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Representative microscopic images of liver sections from control and carbon tetrachloride-treated rats. Tissues were stained for collagen deposition with (A) hematoxylin and eosin, and (B) Masson's trichrome. Original magnification, ×100. CON, control.

The hepatic lobule structure persisted beyond 4 weeks; however, in the CCl4 treatment group the appearance of the hepatic lobules became disorganized, and were characterized by fibrous septa, severe fatty degeneration, hydropic degeneration and focal necrosis. After 6 and 8 weeks of CCl4 treatment, pseudolobules, and inflammatory cell infiltration into the portal areas and fibrous septa were observed. At 12 weeks (or 4 weeks after the final CCl4 injection), fibrous septa began to attenuate or exhibit discontinuous shapes, with some of the fibrous septa becoming barely visible (Fig. 1).

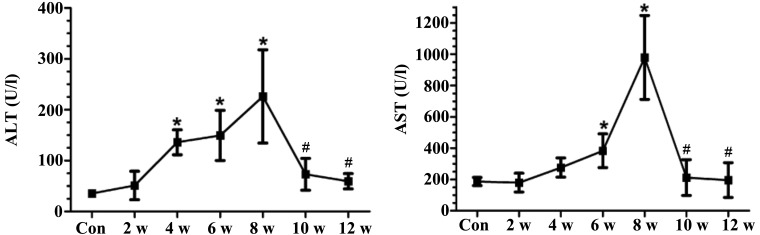

Changes in serum indices of liver function

Treatment with CCl4 (2–8 weeks) resulted in a significant elevation in AST and ALT levels. However, at 10 weeks (2 weeks after the final CCl4 injection), AST and ALT levels were markedly lower compared with those measured at 8 weeks (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Serum ALT and AST activities of carbon tetrachloride-treated and control rats. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation of experiments performed in duplicate (n=6). *P<0.05 vs. the Con group; #P<0.05 vs. the 8 w group. ALT, alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate transaminase; Con, control.

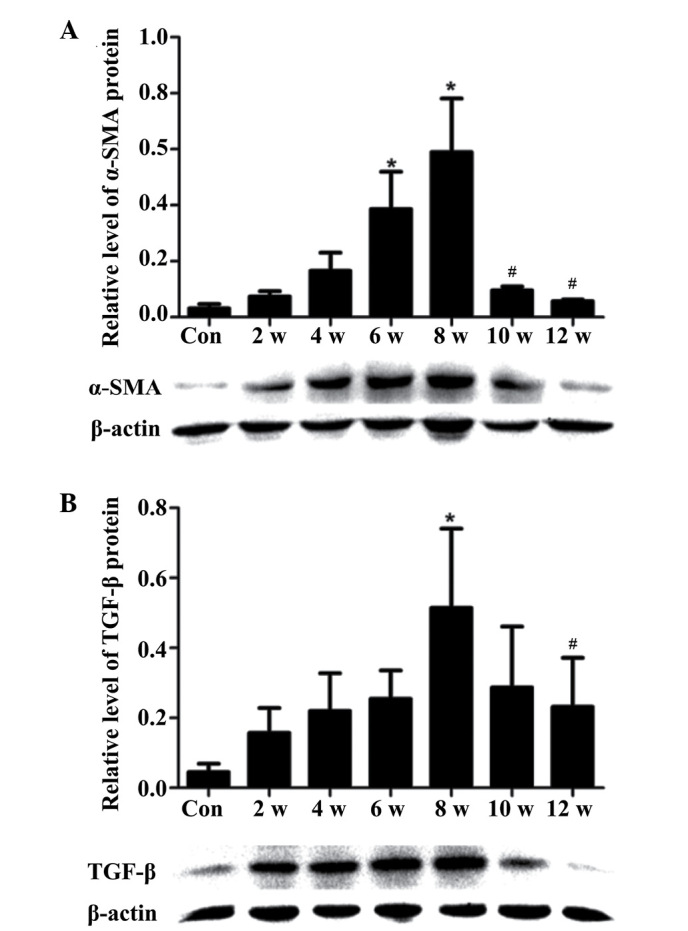

α-SMA and TGF-β protein expression in vivo

α-SMA expression in HSCs reflects myofibroblast-like cell activation, has been directly linked to experimental liver fibrogenesis, and is indirectly associated with fibrosis in chronic human liver disease (20).

The expression levels of α-SMA were increased in the CCl4 treatment group compared with in the control group. However, when CCl4 treatment ceased, protein expression returned to baseline levels (Fig. 3A). In addition, the expression levels of TGF-β were elevated in the CCl4 treatment group (2–8 weeks), and this increase corresponded with the degree of liver fibrosis (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Protein expression levels of α-SMA and TGF-β in carbon tetrachloride-treated and control rats. (A) α-SMA and (B) TGF-β protein expression levels were detected in the liver by western blotting. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation from 6 rats. *P<0.05 vs. the Con group; #P<0.05 vs. the 8 w group. Con, control; α-SMA, α-smooth muscle actin; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-β.

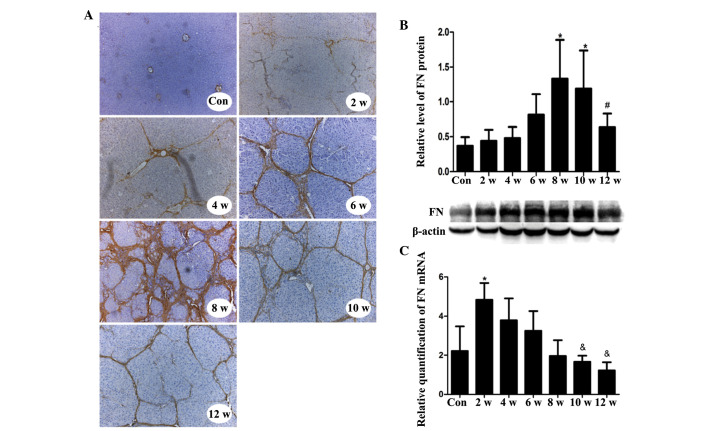

In vivo location, and hepatic mRNA and protein expression levels of FN during hepatic fibrogenesis

Markedly increased FN staining was detected in hepatocytes, sinusoidal areas, extracellular spaces, and portal and central areas in the experimental group tissues compared with in the control tissues, as determined by immunohistochemical staining of FN in liver sections. FN expression increased with increasing fibrosis, and peaked during week 8. However, after week 8 and the discontinuation of CCl4 treatment, FN staining gradually decreased (Fig. 4A). The criterion used to assess FN positivity was yellow or brown staining in the cell membrane or mesenchyme.

Figure 4.

In vivo FN mRNA and protein expression in CCl4-treated and control rats, and the location of FN in liver tissue during the course of hepatic fibrogenesis. (A) FN staining in liver sections from control and CCl4-treated rats. One representative image from each time point is shown. Original magnification, ×200. (B) Protein expression levels of FN in the liver, as detected by western blotting. (C) mRNA expression levels of FN relative to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase, as detected by quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Each sample was analyzed in duplicate (n=6/group). Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. *P<0.05 vs. the Con group; #P<0.05 vs. the 8 w group; &P<0.05 vs. the 2 w group. Con, control; CCl4, carbon tetrachloride; FN, fibronectin.

The protein expression levels of FN in CCl4-injured liver tissues gradually increased during the course of liver fibrogenesis. As detected by western blotting, FN expression reached its maximal point during week 8, after which expression gradually decreased (Fig. 4B). The mRNA expression levels of FN rapidly increased to a maximum level during the first 2 weeks. After the first 2 weeks, expression gradually fell (Fig. 4C).

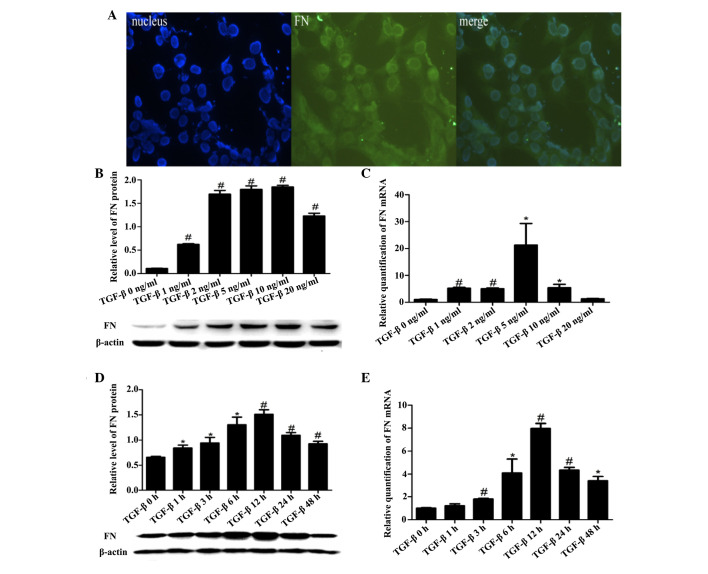

In vitro location, and mRNA and protein expression levels of FN in HSC-T6 cells

Immunofluorescence assays demonstrated that FN was primarily located in the cytoplasm of HSC-T6 cells (Fig. 5A). TGF-β stimulation upregulated the mRNA and protein expression levels of FN in HSC-T6 cells in a dose- and time-dependent manner (Fig. 5B–E).

Figure 5.

FN location, and mRNA and protein expression in HSC-T6 cells. (A) FN immunofluorescence localization in HSC-T6 cells. Blue, nucleus (left); green, target protein (middle); merged green and blue image (right). Magnification, ×40. (B) Protein expression levels of FN in the HSC-T6 cells, as detected by western blotting. (C) mRNA expression levels of FN in HSC-T6 cells, as detected by RT-qPCR. FN expression was normalized to GAPDH (internal control). (B and C) Six concentrations of TGF-β (0, 1, 2, 5, 10 and 20 ng/ml) were assayed. (D) Protein expression levels of FN in the HSC-T6 cells, as detected by western blotting. (E) mRNA expression levels of FN in HSC-T6 cells, as detected by RT-qPCR. FN expression was normalized to GAPDH (internal control). (D and E) Seven time points (0, 1, 3, 6, 12, 24 and 48 h) were assayed, and HSC-T6 cells were stimulated with TGF-β (5 ng/ml). Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. *P<0.05 vs. the Con group; #P<0.01 vs. the Con group. Con, control; HSC, hepatic stellate cells; FN, fibronectin; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-β.

Discussion

Liver fibrosis is a category of interest in liver disease research due to its importance in the natural history of chronic liver diseases. Previous studies have revealed that hepatic fibrogenesis is a dynamic process, and that the capacity for recovery exists from any degree of fibrosis, including established cirrhosis (21,22).

The present study induced hepatic fibrosis in male Wistar rats via intraperitoneal injections of CCl4. This regimen induced major fibrosis, which regressed following the discontinuation of CCl4 treatment. Decreased serum ALT and AST activities, and TGF-β and α-SMA protein levels were detected following the discontinuation of CCl4 treatment, mimicking the clinically observed expression patterns.

The progression of liver fibrosis is characterized by the gradual accumulation of ECM proteins in injured tissue, and HSCs have a crucial role in this fibrotic response (23). Upon liver injury, quiescent HSCs are activated and transdifferentiate into myofibroblast-like cells. These myofibroblast-like cells are characterized by increased proliferation and excessive deposition of ECM proteins (24). In addition, activated HSCs are able to upregulate the expression of cytoskeletal proteins, including α-SMA. Therefore, α-SMA is considered a marker of HSC activation, which may reflect the degree of liver fibrosis (25,26). Alterations to the hepatic architecture occur due to the combined increase in cytoskeletal protein synthesis and the inability to break down these proteins, resulting in liver fibrosis and, eventually, cirrhosis (27). The results of the present study suggested that HSC activation indirectly indicated the level of ECM deposition and the degree of liver fibrosis. In the present study, α-SMA expression was detected at various time points following CCl4 injection, and the results demonstrated that α-SMA expression increased in response to CCl4 treatment, in a time-dependent manner. However, when CCl4 treatment was terminated, α-SMA protein expression returned to baseline. These results suggested that liver fibrosis can be reversed.

Increasing evidence has indicated that TGF-β is a key mediator of liver fibrosis (14,28,29). Myofibroblast differentiation of HSCs is induced by TGF-β, and TGF-β induction results in increased ECM protein production (30). Thus, it is suggested that TGF-β serves an important role in morphogenesis, proliferation and differentiation of cells, and is good for cell repair. With fibrosis of the liver, the expression of TGF-β will increase in order to repair the damaged liver tissue. Thus, TGF-β expression is increased in damaged liver compared with the normal liver.

FN is a non-collagenous glycoprotein with several functions. FN is produced and secreted by fibroblasts, endothelial cells, macrophages and hepatocytes in vivo (31), and its expression is closely associated with hepatic fibrosis, cellular damage, differentiation and repair. In the present study, FN expression increased with increasing CCl4 levels, and decreased when CCl4 injections ceased. Furthermore, FN expression levels were associated with the degree of hepatic fibrosis; however, it was also confirmed that liver fibrosis could be reversed. The present study also demonstrated that FN expression varied during the process of fibrogenesis according to the type of hepatitis (acute or chronic).

In acute hepatitis, fibroblasts proliferate and FN levels increase after liver injury (32,33). Conversely, in chronic hepatitis, FN levels increase due to fibrous tissue hyperplasia; however, due to significant FN deposition in the fibrous tissue, the FN content of the liver appears to fall after the formation of liver fibrosis (34). Nevertheless, the total deposition of FN consistently reflects the degree of liver fibrosis and the degree of ECM deposition, and is an important marker of hepatic fibrosis.

The in vivo experiments conducted in the present study were designed to simulate chronic hepatitis, and the results indicated that the mRNA expression levels of FN peaked as early as at 2 weeks. The time lag between FN mRNA expression and the expression of the corresponding protein may be related to the time required for FN synthesis in the liver. The detected upregulated mRNA levels may represent activation of the promoter or enhancer, or of upstream transcription factors; however, whereas protein levels are usually coupled to the biological function of the proteins themselves, this is not always true for the corresponding mRNA levels.

The in vitro experiments conducted in the present study were designed to more closely represent the conditions present during acute hepatitis. The results indicated that FN mRNA expression corresponded with FN protein expression, with peak mRNA and protein expression values observed in response to the same concentration and duration of TGF-β stimulation. The above results indicate that the protein expression may not be consistent with the corresponding RNA expression in the chronic hepatitis model, however, in the acute hepatitis model, the expression of these two indexes tended to be consistent.

In conclusion, the present study confirmed the reversibility of liver fibrosis. This was true even after the establishment of cirrhosis. The results indicated that FN may have an early and critical role during the process of liver fibrogenesis. The in vivo and in vitro models exhibited marked differences in FN expression, and these differences may closely resemble those between chronic and acute human hepatitis.

Acknowledgments

The present study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81300334) and the WBE Liver Fibrosis Foundation (grant no. CFHPC20120145). The authors would like to thank Medjaden Bioscience Limited for assisting in the preparation of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Cong M, Liu T, Wang P, Fan X, Yang A, Bai Y, Peng Z, Wu P, Tong X, Chen J, et al. Antifibrotic effects of a recombinant adeno-associated virus carrying small interfering RNA targeting TIMP-1 in rat liver fibrosis. Am J Pathol. 2013;182:1607–1616. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xu G, Niki T, Virtanen I, Rogiers V, De Bleser P, Geerts A. Gene expression and synthesis of fibronectin isoforms in rat hepatic stellate cells. Comparison with liver parenchymal cells and skin fibroblasts. J Pathol. 1997;183:90–98. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199709)183:1<90::AID-PATH1105>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matsui S, Takahashi T, Oyanagi Y, Takahashi S, Boku S, Takahashi K, Furukawa K, Arai F, Asakura H. Expression, localization and alternative splicing pattern of fibronectin messenger RNA in fibrotic human liver and hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 1997;27:843–853. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(97)80322-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sottile J, Hocking DC. Fibronectin polymerization regulates the composition and stability of extracellular matrix fibrils and cell-matrix adhesions. MolBiol Cell. 2002;13:3546–3559. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-01-0048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Velling T, Risteli J, Wennerberg K, Mosher DF, Johansson S. Polymerization of type I and III collagens is dependent on fibronectin and enhanced by integrins alpha 11beta 1 and alpha 2beta 1. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:37377–37381. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206286200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roeb E, Matern S. Fibronectin-a key substance in pathogenesis of liver cirrhosis? Leber Magen Darm. 1993;23:239–242. In German. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manabe R, Oh-e N, Sekiguchi K. Alternatively spliced EDA segment regulates fibronectin-dependent cell cycle progression and mitogenic signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:5919–5924. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.9.5919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krzyzanowska-Gołab D, Lemańska-Perek A, Katnik-Prastowska I. Fibronectin as an active component of the extracellular matrix. Postepy Hig Med Dosw (Online) 2007;61:655–663. In Polish. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leite AR, Corrêa-Giannella ML, Dagli ML, Fortes MA, Vegas VM, Giannella-Neto D. Fibronectin and laminin induce expression of islet cell markers in hepatic oval cells in culture. Cell Tissue Res. 2007;327:529–537. doi: 10.1007/s00441-006-0340-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mòdol T, Brice N, Ruiz de Galarreta R, García Garzón A, Iraburu MJ, Martínez-Irujo JJ, López-Zabalza MJ. Fibronectin peptides as potential regulators of hepatic fibrosis through apoptosis of hepatic stellate cells. J Cell Physiol. 2015;230:546–553. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kawelke N, Vasel M, Sens C, Av A, Dooley S, Nakchbandi IA. Fibronectin protects from excessive liver fibrosis by modulating the availability of and responsiveness of stellate cells to active TGF-β. PLoS One. 2011;6:e28181. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Altrock E, Sens C, Wuerfel C, Vasel M, Kawelke N, Dooley S, Sottile J, Nakchbandi IA. Inhibition of fibronectin deposition improves experimental liver fibrosis. J Hepatol. 2015;62:625–633. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parsons CJ, Takashima M, Rippe RA. Molecular mechanisms of hepatic fibrogenesis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22(Suppl 1):S79–S84. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Inagaki Y, Okazaki I. Emerging insights into Transforming growth factor beta Smad signal in hepatic fibrogenesis. Gut. 2007;56:284–292. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.088690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reitman S, Frankel S. A colorimetric method for the determination of serum glutamic oxalacetic and glutamic pyruvic transaminases. Am J Clin Pathol. 1957;28:56–63. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/28.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta DeltaC(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang X, Yang J, Li Y, Liu Y. Both Sp1 and Smad participate in mediating TGF-beta1-induced HGF receptor expression in renal epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;288:F16–F26. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00318.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ruwart MJ, Wilkinson KF, Rush BD, Vidmar TJ, Peters KM, Henley KS, Appelman HD, Kim KY, Schuppan D, Hahn EG. The integrated value of serum procollagen III peptide over time predicts hepatic hydroxyproline content and stainable collagen in a model of dietary cirrhosis in the rat. Hepatology. 1989;10:801–806. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840100509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lan HY, Mu W, Nikolic-Paterson DJ, Atkins RC. A novel, simple, reliable, and sensitive method for multiple immunoenzyme staining: Use of microwave oven heating to block antibody crossreactivity and retrieve antigens. J Histochem Cytochem. 1995;43:97–102. doi: 10.1177/43.1.7822770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carpino G, Morini S, Ginanni Corradini S, Franchitto A, Merli M, Siciliano M, Gentili F, Onetti Muda A, Berloco P, Rossi M, et al. Alpha-SMA expression in hepatic stellate cells and quantitative analysis of hepatic fibrosis in cirrhosis and in recurrent chronic hepatitis after liver transplantation. Dig Liver Dis. 2005;37:349–356. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sohrabpour AA, Mohamadnejad M, Malekzadeh R. Review article: The reversibility of cirrhosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36:824–832. doi: 10.1111/apt.12044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brenner DA. Reversibility of liver fibrosis. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2013;9:737–739. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bataller R, Brenner DA. Liver fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:209–218. doi: 10.1172/JCI24282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Foo NP, Lin SH, Lee YH, Wu MJ, Wang YJ. α-Lipoic acid inhibits liver fibrosis through the attenuation of ROS-triggered signaling in hepatic stellate cells activated by PDGF and TGF-α. Toxicology. 2011;282:39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2011.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Friedman SL. Hepatic stellate cells: Protean, multifunctional, and enigmatic cells of the liver. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:125–172. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00013.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bae MA, Rhee SD, Jung WH, Ahn JH, Song BJ, Cheon HG. Selective inhibition of activated stellate cells and protection from carbon tetrachloride-induced liver injury in rats by a new PPARgamma agonist KR62776. Arch Pharm Res. 2010;33:433–442. doi: 10.1007/s12272-010-0313-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Svegliati-Baroni G, De Minicis S, Marzioni M. Hepatic fibrogenesis in response to chronic liver injury: Novel insights on the role of cell-to-cell interaction and transition. Liver Int. 2008;28:1052–1064. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meindl-Beinker NM, Dooley S. Transforming growth factor-beta and hepatocyte transdifferentiation in liver fibrogenesis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23(Suppl 1):S122–S127. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.05297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arauz J, Zarco N, Segovia J, Shibayama M, Tsutsumi V, Muriel P. Caffeine prevents experimental liver fibrosis by blocking the expression of TGF-β. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;26:164–273. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3283644e26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gressner AM, Weiskirchen R. Modern pathogenetic concepts of liver fibrosis suggest stellate cells and TGF-beta as major players and therapeutic targets. J Cell Mol Med. 2006;10:76–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2006.tb00292.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mosesson MW. Fibrinogen and fibrin and structure and functions. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3:1894–1904. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wielockx B, Lannoy K, Shapiro SD, Itoh T, Itohara S, Vandekerckhove J, Libert C. Inhibition of matrix metalloproteinases blocks lethal hepatitis and apoptosis induced by tumor necrosis factor and allows safe antitumor therapy. Nat Med. 2001;7:1202–1208. doi: 10.1038/nm1101-1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leu JI, Crissey MA, Taub R. Massive hepatic apoptosis associated with TGF-beta1 activation after Fas ligand treatment of IGF binding protein-1-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:129–139. doi: 10.1172/JCI200316712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kandemir O, Polat G, Sahin E, Bagdatoglu O, Camdeviren H, Kaya A. Fibronectin levels in chronic viral hepatitis and response of this protein to interferon therapy. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51:811–814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]