Abstract

Although social and nonsocial fear are discernable as early as preschool, little is known about their distinct associations with developmental outcomes. For example, fear has been identified as a predictor of social anxiety problems, but no work has examined whether social and nonsocial fear make independent contributions to risk. We investigated the extent to which early social and non-social fear were associated with socially anxious behaviors during kindergarten. To do this, we identified distinct trajectories of social and nonsocial fear across toddlerhood and preschool. Only social fear was associated with socially anxious behaviors at ages 2 and 5. Because the ability to regulate fear contributes to the degree to which fearful children are at risk for anxiety problems, we also tested whether an early-developing aspect of self-regulation modulated associations between early fear and kindergarten socially anxious behaviors. Specifically, we tested whether inhibitory control differentially modulated associations between early levels of social and nonsocial fear and socially anxious behaviors during kindergarten. Associations between trajectories of early social fear and age 5 socially anxious behaviors were moderated by individual differences in inhibitory control. Consistent with previous research showing associations between overcontrol and anxiety symptoms, more negative outcomes were observed when stable, high levels of social fear across childhood were coupled with high levels of inhibitory control. Results suggest that the combination of social fear and overcontrol reflect a profile of early risk for the development of social inhibition and social anxiety problems.

Keywords: Social Fear, Nonsocial Fear, Inhibitory Control, Social Anxiety Risk

Heightened temperamental fearfulness is an early risk factor for Social Anxiety Disorder (Buss, 2011; Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2009; Volbrecht & Goldsmith, 2010). Recently, fear in social contexts was shown to be unique from nonsocial fear (Dyson, Klein, Olino, Dougherty, & Durbin, 2011; Scarr & Salapatek, 1970). The unique developmental trajectories of different types of fear have not been delineated, making it difficult to understand whether distinguishing between developing social and nonsocial fear might enhance our understanding of the links between early fear and early risk for disorder. Identifying how non-fear characteristics may modulate associations between early fearfulness and socially anxious behaviors would also further enhance our understanding of the nature of early risk. Currently, self-regulatory behaviors, which may be necessary for dampening fear responses, have been linked to both mitigated (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 1995; Moffitt et al., 2011) and exacerbated (e.g., Brooker et al., 2011; Kiel & Buss, 2011) anxiety risk. Distinguishing between social and nonsocial fear, which have largely been combined in prior research, may help to clarify the nature of associations among fear, self-regulation, and early risk.

To address gaps in the current literature, we examined early trajectories of social and nonsocial fear and their unique associations with early social inhibition, defined as withdrawal and avoidance in novel social contexts (Rubin & Asendorpf, 1993), and early socially anxious behaviors. We also tested an early-developing aspect of self-regulation, inhibitory control (i.e., the ability to inhibit a prepotent behavioral response (Rothbart & Bates, 1998)), as a moderator of associations between social and nonsocial fear and early risk.

Developmental Trajectories of Fear and Risk for Anxiety Problems

Goldsmith and Campos (1982) define temperament as individual differences in propensities for experiencing the primary emotions. Greater temperamental fear, assessed through observations of fear behaviors (e.g., fear expressions, freezing, crying, etc.), is linked to increased risk for anxiety problems in typically-developing children (Buss, 2011). Temperamentally fearful children are at particular risk for Social Anxiety Disorder, though other anxiety diagnoses are not uncommon (Biederman et al., 2001; Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2009). Similar risk exists for related fear-based constructs. For example, behaviorally inhibited children, a group characterized by extreme levels of fear and reactivity to novelty during infancy, are at high risk for anxiety problems during adolescence (Biederman et al., 2001; Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2009). Similarly, shy children, characterized both by fear and social-evaluative concerns (Rubin & Asendorpf, 1993), are at greater risk for anxiety problems relative to non-shy children (Volbrecht & Goldsmith, 2010). We focus our report on temperamental fearfulness, the basic common unit linking fear with broader constructs such as inhibition and shyness.

There is limited stability between early fear and later disorder (Clauss & Blackford, 2012), which has made it difficult to determine which children are most at risk. Thus, efforts to refine the aspects of early fear that may be most relevant for long-term risk are increasing. Such efforts have included mapping trajectories of developing fear, using temporal information to aid in predicting risk. On average, fearfulness increases during infancy (Brooker et al., 2013; Gartstein et al., 2010), before declining over time (Côté, Tremblay, Nagin, Zoccolillo, & Vitaro, 2002). Atypical trajectories, including sustained high levels of fear or steeper-than-average increases in early fear are associated with a greater risk for disorder. For example, steep increases in infant fear in the first year of life are associated with more severe anxious behaviors in toddlerhood (Gartstein et al., 2010). Similarly, the link between early fear and anxiety risk is strongly tied to stability in high levels of fear from 2 to 7.5 years of age (Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2009; Hirshfeld et al., 1992).

Early fear is a particularly robust predictor of Social Anxiety Disorder (Hirshfeld-Becker et al., 2007), suggesting that the development of social fear may be of particular importance for identifying early risk for social anxiety problems. Consistent with a definition of social fear as distress in the presence of novel social partners, the literature on developing social fear focuses primarily on early fear of strangers. Mirroring the normative trajectory of more global fear measures, stranger fear increases in the first year of life (Emde, Gaensbauer, & Harmon, 1976; Sroufe, 1977). During late childhood and adolescence, social-evaluative fears also increase (Westenberg, Gullone, Bokhorst, Heyne, & King, 2007), though it is unclear whether this trajectory is linked to social fear during infancy. To our knowledge, only one study has isolated developmental trajectories of social fear, reporting four independent patterns between 6 and 36 months of age (Brooker et al., 2013). Although most infants followed the normative trajectory of increasing stranger fear, a substantial number followed a trajectory of sustained, high levels of fear over time similar to that associated with risk for social anxiety problems (Hirshfeld et al., 1992). However, because no comparison was made to nonsocial fear, it is unclear whether these trajectories are specific to developing social fear or whether they reflect fear development more broadly. We examined this in the current study.

Relative to social fear, less is known about nonsocial fear development, defined as distress in the presence of objects or nature. One cross-sectional study found that 30% – 40% of infants responded with fear to the presentation of novel objects by 7 months of age, well before stranger fear emerged (Scarr & Salapatek, 1970). This work also suggested that nonsocial fear was stable in the first year of life. Presumably, fearfulness toward unfamiliar objects would become adaptive later in development, as children's mobility and independence continued to increase. While this has not yet been investigated empirically, theories about fear development have suggested that unique critical periods may exist for the maturation of different types of fear (Bronson, 1965; Hebb, 1946; Hess, 1959).

Despite possible differences across development, social and nonsocial fear measures are most frequently composited in multi-method assessments of a single fear construct (Buss, 2011; Fox, Henderson, Rubin, Calkins, & Schmidt, 2001; Goldsmith, 1996; Rothbart, Ahadi, Hershey, & Fisher, 2001). Thus, developmental differences in associations between different types of fear and social anxiety risk are not well understood. Cross-sectional, empirical studies have shown a distinction between social and nonsocial fear in infants and young children, suggesting that anxious behaviors are more strongly associated with social than with nonsocial fear (Dyson et al., 2011; Scarr & Salapatek, 1970). However, the possibility that developmental trajectories may further distinguish the roles of social and nonsocial fear in early risk for social anxiety problems remains untested. We addressed this in the current study.

Inhibitory Control and Risk for Anxiety Problems

Although distinguishing trajectories of social and nonsocial fear will be important for fully understanding the nature of early risk, inconsistent relations between early fear and problems with social anxiety may also indicate the presence of moderators in child outcomes. Regulatory aspects of temperament may be particularly important to examine. Inhibitory control is an early-appearing dimension of self-regulation and comprises one facet of broader regulatory constructs such as effortful control, cognitive control, and executive function. Defined as the ability to inhibit a dominant or prepotent behavioral response (Rothbart & Bates, 2006), inhibitory control can be measured as early as infancy through paradigms that stress the suppression of inappropriate or incorrect responses (Kochanska, Murray, Jacques, Koenig, & Vandegeest, 1996). In the current study, we adopt this view of inhibitory control as an early-developing facet of self-regulation.

Inhibitory control emerges for most children in the second year of life (Kochanska, Murray, & Harlan, 2000; Rothbart & Bates, 2006), increases throughout childhood (Williams, Ponesse, Schachar, Logan, & Tannock, 1999), and remains relatively stable thereafter. Increases in inhibitory control are thought to depend primarily on the maturation of structures that support control over behavior, including the prefrontal cortex and anterior cingulate (Posner & Rothbart, 1998; Rothbart & Ahadi, 1994).

Traditional theories assume that greater inhibitory control is inherently adaptive. In general, greater inhibitory control appears to enable the down-regulation of negative emotions (Saarni, 1984). Individual differences in inhibitory control are most frequently examined in association with externalizing outcomes, with most research reporting negative associations between inhibitory control and childhood externalizing problems (Buss, Kiel, Morales, & Robinson, 2014; Kochanska & Knaack, 2003).

Links between inhibitory control and internalizing problems, such as anxiety, are less clear. At least one study has reported that greater inhibitory control is associated with fewer internalizing symptoms (Eisenberg et al., 2001). This work assessed, using both parent-reported and observed control, links between the measures of delay and persistence and internalizing symptoms in a cross-sectional sample of children (Mage = 73.58 months). In contrast, other work has shown positive associations between inhibitory control and internalizing behaviors (Murray & Kochanska, 2002). This work focused on broad assessments of observed control from toddlerhood through school age, incorporating delay and persistence along with slowing down, response inhibition, and effortful attention.

Although both approaches offer important information about links between regulation and children's behavior problems, Murray and Kochanska's longitudinal design included children as young as age 2, making it more likely to capture variability in developing social fear as it peaks and declines early in life. Thus, associations between developing social fear and inhibitory control that are related to early risk may have been more evident via a longitudinal design that includes the toddler period. Thus, this was the approach used in the current study.

The implication of using different behavioral composites is less clear. Broad assessments of inhibitory control indicate associations between low levels of control and a range of problematic outcomes (Moffitt et al., 2011). However, recent developmental neuroscience research supports the notion that anxiety risk, in particular, is associated with behavioral over-control and hyper-monitoring (Brooker & Buss, 2014; Santesso, Segalowitz, & Schmidt, 2006; Torpey, Hajcak, & Klein, 2009). Practically, this suggests that the inhibition of behaviors or responses when such inhibition is unnecessary may be maladaptive. Such ideas align with developmental psychopathology theory, from which links between over-control and risk for internalizing problems have been posited (Nigg, 2000).

It is important to note that the degree to which behaviors such as inhibitory control are truly adaptive is dependent on context, goals, and outcomes. Perspectives on emotion regulation have underscored the importance of one's ability to accurately perceive changing contextual demands and flexibly apply regulatory strategies (Bonanno & Burton, 2013; Kashdan & Rottenberg, 2010; Ryan, La Guardia, Solky-Butzel, Chirkov, & Kim, 2005). Given evidence that social and nonsocial fear are distinct constructs, may follow unique developmental pathways, and are elicited by unique contextual demands (Dyson et al., 2011; Scarr & Salapatek, 1970), the utility of inhibitory control as a regulator of fear responses may not be universal (Bonanno & Burton, 2013). For these reasons, the degree to which fear composites have mixed social versus nonsocial assessments of fear may be contributing to mixed results in the literature. Thus, a final aim of the current study was to test early inhibitory control as a moderator of longitudinal links between both social and nonsocial fear and social anxiety risk.

The Current Study

In sum, we addressed three primary aims. First, we isolated separate trajectories of social and nonsocial fear across the toddler and preschool years given that these ages (1) overlap with both previous work on longitudinal trajectories of fear and prior work distinguishing social from nonsocial fear, (2) may capture critical periods of fear development, (3) evidence broad individual differences in fear, and (3) produce associations between fear and risk for social anxiety problems. Based on previous work suggesting cross-sectional differences in the observations of social and nonsocial fear across early development (Scarr & Salapatek, 1970), we hypothesized that social and nonsocial fear would follow distinct developmental trajectories across toddlerhood and preschool.

Second, we tested whether trajectories of social and nonsocial fear uniquely predicted behaviors indicative of social anxiety. Based on previous work by Dyson and colleagues (2011), we hypothesized that trajectories of social fear would be more strongly associated with socially anxious behaviors than would trajectories of nonsocial fear. Specifically, we expected that children with stable, high levels of social fear over time would show the greatest number of socially anxious behaviors.

Finally, we tested whether inhibitory control moderated associations between fear trajectories and socially anxious behaviors. We decided a priori to test inhibitory control as a moderator of both the association between social fear and socially anxious behaviors and also the association between nonsocial fear and socially anxious behaviors. Given the relevance of social fear to anxiety symptoms (Dyson et al., 2011) and recent evidence linking early overcontrol with early fear (Brooker & Buss, 2014; Murray & Kochanska, 2002), we expected that trajectories of high social fear coupled with high inhibitory control would be associated with greater numbers of socially anxious behaviors at age 5. We expected less robust associations between nonsocial fear and inhibitory control in relation to socially anxious behaviors.

Method

Participants

Participants were 111 2-year-olds (M = 2.00; range 1.5–2.5; 55% boys) recruited from a Midwestern US city and surrounding rural county. Only families with infants weighing more than 5.5 lbs. at birth, as noted in birth records published in local newspapers, were contacted for recruitment. Consistent with the area from which they were recruited, the sample was largely middle-class (Hollingshead index: M = 48.84; SD = 10.55; range 17–66) and predominantly (90.1%) non-Hispanic European American (3.6% African-American, 3.6% Hispanic, 1.8% Asian-American, 0.09% Indian-American). Most parents were married (< 2% divorced or single-parent at first assessment; 6% at final assessment).

Follow-up assessments were conducted via mail at ages 3 and 4 (total follow-up of 95 children; 86% participation). Follow-up assessments also occurred during the kindergarten year. As part of this, participants, unfamiliar to one another, returned to the laboratory in groups of 3–4 same-sex peers (85% participation). Families who did and did not participate in follow-up assessments did not differ (Buss, 2011). One child received a diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder during the follow-up period and was excluded from analyses.

Procedures

Recruitment

Families were mailed letters describing the study and asking that they return an informational postcard if interested in participating. Parents who returned the postcard were contacted via phone to schedule a time to visit the laboratory.

Questionnaires

The primary caregiver completed a battery of questionnaires assessing child temperament along with early child mental and physical health at child ages 2, 3, and 4. Parents completed the same questionnaire battery one-month prior to kindergarten entry (Age 5 Fall) and in the spring of the kindergarten year (Age 5 Spring).

Age 2 laboratory visit

At age 2, children participated in six laboratory episodes from the toddler version of the Laboratory Temperament Assessment Battery (Lab-TAB; Buss & Goldsmith, 2000). The order of episodes was partially counterbalanced such that children did not participate in consecutive episodes that targeted the same emotion (i.e., 2 consecutive fear episodes); an equal number of girls and boys completed each episode order. Parents remained present throughout the laboratory episodes in order to avoid inducing child distress due to parent-child separation. The Puppet Show and Clown episodes each lasted approximately 3 minutes. In these episodes, either two friendly puppets or a friendly, unfamiliar female experimenter dressed as a clown presented a series of age-appropriate toys and invited toddlers to play. The Stranger Approach and Stranger Working episodes each lasted approximately 2 minutes. In Stranger Approach, an unfamiliar male experimenter entered the room and attempted to engage the child in conversation while gradually approaching the child, eventually sitting down within 2 feet of him/her. In Stranger Working, an unfamiliar female experimenter entered the room holding a clipboard, walked to a desk at the far end of the room, and pretended to “work.” She only interacted with the child if the child initiated conversation. The Spider and Robot episodes each lasted approximately one minute. In Spider, the child sat opposite a large spider mounted on a remote-controlled vehicle. An unseen experimenter in a control room manipulated the spider so that it gradually approached the child, coming all the way up to him/her. In Robot, children sat facing a platform containing a remote-controlled toy robot. An experimenter in a different room manipulated the robot so that it appeared to move independently around the platform. All episodes were video-recorded through a one-way mirror.

Age 5 laboratory visit

At age 5, an experimenter led children, in groups of 3–4 unfamiliar, same-aged, same-sex peers, into a room filled with age-appropriate toys. Similar to previous procedures designed to tap anxious behaviors (Coplan, Rubin, Fox, Calkins, & Stewart, 1994), children were told that they could play with the toys however they liked. The experimenter then left the room and children were allowed to engage in unstructured play for 15 minutes. The episode was recorded through a one-way mirror.

Measures

Parent-reported social and nonsocial fear

Children's levels of social and nonsocial fear were defined as typical levels of fear in social (i.e., people) and nonsocial (i.e., objects or nature) contexts according to parent reports. Primary caregivers completed age-appropriate temperament questionnaires at child ages 2 (Toddler Behavior Assessment Questionnaire (TBAQ); Goldsmith, 1996), 3, 4, and 5 years (Fall and Spring; Children's Behavior Questionnaire (CBQ); Rothbart et al., 2001). Questions from the TBAQ object fear and CBQ fear scales are highly overlapping, asking about children's fears of the dark, loud noises, storms, and either real (e.g., bugs) or pretend “monsters.” Sample questions from the 10-item scale on the TBAQ included “When a dog or other large animal approached your child, how often did s/he cling to you?” and “When hearing loud noises, how often did s/he become distressed?” Sample questions from the 6-item scale on the CBQ included “Is frightened by “monsters” seen on TV or at movies” and “Is afraid of loud noises.” Because questions focus on children's fear in response to nonsocial stimuli, these scales were used as age-appropriate measures of nonsocial fear.

Questions from the TBAQ social fear and CBQ shyness scales are similarly overlapping, asking about children's comfort and levels of activity and interaction with familiar and unfamiliar individuals. Sample questions from the 10-item scale on the TBAQ included “When your child was approached by a stranger when you and s/he were out, how often did your child show distress or cry?” and “When one of the parents' friends who did not have daily contact with your child visited the home, how often did your child talk much less than usual?” Sample questions from the 6-item scale on the CBQ included “Acts shy around new people” and “Sometimes turns away shyly from new acquaintances.” Because of their focus on children's fear responses to social interactions, these scales were used as age-appropriate measures of social fear.

TBAQ and CBQ scales have demonstrated construct equivalence over time (Goldsmith, Buss, & Lemery, 1997) and have been used together to model longitudinal fear development (Brooker et al., 2013). Given suggestions that it is necessary to adjust longitudinal measures to remain sensitive to developmental stage (Knight & Zerr, 2010), we prioritized construct definitions based on temperament theory in our examination of the development of social and nonsocial fear; thus, unadjusted raw TBAQ and CBQ scores were used1.

The TBAQ and CBQ asked parents to rate, on identical seven-point scales, the frequency with which their child has displayed numerous behaviors during the previous month (1 = never; 7 = always). The reliability of all scales was high (mean α = 0.77 across scales and ages).

Anxious behaviors

Observed dysregulated fear at age 2

Dysregulated fear was defined as a mismatch between observed fear and both (a) normative patterns of fear across episodes and (b) the incentive properties of emotion-eliciting contexts (Cole, Michel, & Teti, 1994). Based on this definition, dysregulated fear was derived from patterns of observed fear across emotion-eliciting episodes at age 2. Because dysregulated fear is intended to contrast children's displays of fear across contexts, it is most beneficial to include a variety of contexts in its calculation. As a result, both nonsocial and social contexts are included in its calculation.

Facial fear, bodily fear, freezing, and proximity to caregiver in each of the 6 laboratory episodes were reliably (κ > .65; agreement > 80%) micro-coded on a second-by-second basis for each episode. Facial fear was coded using the AFFEX system, which differentiates emotion expressions based on three regions of the face (Izard, Dougherty, & Hembree, 1983). Fear was coded when brows were straight and raised, eyes were open wide, and mouth was open with corners pulled back. Bodily expressions of fear were coded when activity was diminished, children remained still/rigid for more than two consecutive seconds, and/or muscles appeared tensed or trembling. Proximity to caregiver was scored when the child was within approximately 2 ft. of their caregiver. A PCA was conducted for each episode. In each analysis, a factor emerged which accounted for approximately 25% of the variance in the original variables and included the duration or timing of each fear behavior. Fear behaviors were thus composited into a single variable for each episode (ICCs: 0.61 – 0.73) that indexed the proportion of time that children were engaged in fear behaviors.

As reported previously (Buss, 2011), comparisons of fear composites revealed that the Spider and Robot episodes elicited the most fear (M = 37.79, SD = 17.48) while Clown and Puppet Show elicited the least fear (M = 23.49, SD = 22.92). Based on this pattern, episodes were ordered according to the average amount of fear elicited by the episode (lowest to highest). Episode ordering took into account only levels of fear; episode ordering did not distinguish between social and nonsocial fear. Ordered in this way, a typical pattern of fear across contexts would be such that children generally showed the least fear in the Clown and Puppet Show episodes, more fear in the Stranger Approach and Stranger Working episodes, and the most fear in the Robot and Spider episodes. That is, children would typically show increases in fear as the episodes increased in putative threat.

In order to characterize individual patterns of fear dysregulation, multilevel models were used to create an individual slope of observed fear across the 6 episodes for each child. On average, children showed increases, in fearfulness across episodes (Buss, 2011). Because increases in fear was expected across the episodes, more positive slope values indicated better regulation/less dysregulation, as fearfulness remained consistent with eliciting contexts (Cole et al., 1994) and normative patterns of emotion across contexts. Flat (i.e., consistently high or consistently low fear, despite changes in threat) or more negative (i.e., decreasing fear despite increasing threat) slope values indicated greater fear dysregulation. We categorized dysregulated fear as an anxious behavior given its consistency with diagnostic criteria describing unnecessarily high levels of fear and avoidance that interfere with typical or normative function (DSM-5, 2013).

Socially anxious behaviors with peers at age 5

The Play Observation Scale was used to code children's behavior during free play with their peers (Rubin, 2001). Engagement in solitary, parallel, and group play was coded along with instances of anxious and aggressive behaviors. Data were scanned for groups that were outliers on behaviors that may have influenced the presence of anxious behaviors (e.g, aggressiveness). No groups were found to fit this description. The total proportion of each behavior was entered into a PCA. Three factors emerged that accounted for 70.64% of the variance in the original variables. The first factor (average loading = 0.77) reflected anxious behaviors with peers and had high positive loadings for reticent behaviors (watching others play without engaging, playing in parallel to others, avoiding conversations), anxious behaviors (displays of wariness), and hovering (watching other children play nearby [<3 ft]). This factor was defined as a socially anxious behavior given its consistency with diagnostic criteria describing excessive fear and avoidance of interacting with others (Social Anxiety Disorder; DSM-5, 2013). Regression-based factor scores reflecting anxious behaviors with peers were saved during the analysis. Additional factors reflected aggressive behaviors and solitary play, neither of which were explored further.

Parent-reported social inhibition at age 5

During the age 5 mailing, primary caregivers completed the MacArthur Health Behavior Questionnaire (HBQ; Essex et al., 2002), which assesses a variety of behaviors that index mental and physical health in children. Respondents rated, on a three-point scale (0 = never true, 2 = often or very true), the degree to which behaviors were characteristic of their child in the past six months. Given study hypotheses, we focused on the Social Inhibition scale, which contained 3 items (α = 0.72) asking parents to rate the degree to which their child was shy with strangers, unfamiliar adults, and other children. Scale scores served as a measure of anxious behaviors, given the role of the HBQ in providing developmentally-sensitive assessments of precursors to adult symptoms consistent with social anxiety disorder (DSM-5, 2013; Essex et al., 2002).

Inhibitory Control

Inhibitory control at age 2 was assessed using both parent report and observational methods. During the laboratory visit, children participated in a Snack Delay episode, comprising six trials requiring children to wait between 0 and 30 sec before eating a treat placed in front of them. Trained coders scored the number of seconds the child was able to wait on each trial and a total wait score reflecting inhibitory control was calculated (κ = 0.89).

A scale of inhibitory control is also included on the TBAQ. Thus, parents provided ratings (1 = never; 7 = always) of children's ability to wait or suppress impulsivity in normative situations requiring behavioral control. The scale's internal consistency was high (α = 0.82).

On average, children were able to wait during Snack Delay trials (Mtrials = 4.45, SD = 1.58) and substantial variability was seen in the number of seconds that each child was able to wait (Msec = 11.56, SD = 4.92). A PCA suggested that a single component comprising children's observed and parent-reported inhibitory control accounted for 59.13% of the variance in the original variables (factor scores = 0.77). Thus, a standardized composite was formed to index inhibitory control per the definition of inhibitory control as the ability to suppress a prepotent response in the service of employing a subdominant response (Rothbart & Bates, 1998).

Plan for Analysis

To test the hypothesis that that social and nonsocial fear would follow distinct developmental trajectories across toddlerhood and preschool, we examined heterogeneity in the development of social and nonsocial fear using Latent Class Growth Analyses (LCGA; MPlus Version 4: Muthén & Muthén, 2006), which identifies latent classes whose trajectories differ from the overall sample by relaxing the assumption that all individuals are drawn from a single population (Jung & Wickrama, 2008; Muthén, 2004). Doing so allows for the emergence of different groups that follow their own developmental trajectories. Models were centered at the first assessment age and slopes reflecting changes in social or nonsocial fear were estimated for each group. Relative to assessments at ages 2–4, the final two assessments were spaced unequally (spring and fall of the kindergarten year); this was accounted for in the growth weight parameters. Analyses began with a 1-class solution and progressed until additional classes no longer improved model fit. All final models were judged to be of adequate fit as suggested by fit indices.

The LCGA approach was selected above a continuous-measure approach for two reasons. First, LCGA allows for subsets of groups that follow qualitatively distinct patterns relative to the overall sample. That is, not all members of the sample are assumed to follow the trajectory that is indicated by the mean-level change, as is the case with traditional growth models. Thus, this approach allows us to identify the presence and nature of non-normative fear development over time. Second, to the extent that the current work is intended to inform targeted programs of prevention and intervention, LCGA approaches can lead to practical cutoffs for identifying children who are most at risk.

Following the LCGA, we tested the hypothesis that that stable, high levels of social fear over time would be associated with the greatest number of socially anxious behaviors using Analyses of Variance (ANOVAs). Trajectories of social and nonsocial fear were included in separate models to examine the specificity of findings to social fear. Significant effects in separate models were compared using effect sizes.

Finally, we used hierarchical regression models to test the hypothesis that high levels of inhibitory control coupled with trajectories of high social fear would predict greater numbers of socially anxious behaviors at age 5. Analyses focused on age 5 anxious behaviors in order to take advantage of the longitudinal nature of the data, allowing for stronger inferences than would cross-sectional data.

Missing Data

Rates of missing data ranged from 9.1% children missing observed social and nonsocial fear at age 2 to 47.1% of children missing parent-reported fearfulness at the age 4 assessment. On average, roughly 25% of data were missing from assessments. An analysis of patterns of missing data suggested that data were missing completely at random (Little's MCAR χ2 (262)=268.90, p > 0.10). Under these conditions, it is appropriate to employ a Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML) procedure to account for missing data in the estimation of LCGA classes in Mplus (Graham, 2009). Given that the highest proportion of missing data was in measures used in the creation of latent profile groups rather than validation or outcome measures (i.e., most validation and outcome variables had less than 10% missing values), subsequent analyses using profile groupings were conducted as complete-case analyses.

Results

Descriptive Statistics, Bivariate Associations, and Sex Differences

Means and bivariate correlations are shown in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. Nonsocial fear was significantly correlated at adjacent assessments, but correlations decreased as time between assessments increased and became more variable.

Table 1.

Means and standard deviations for primary variables

| n | Min | Max | M | SD | t | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age 2 Social Fear | 107 | 1.60 | 6.00 | 3.44 | 1.04 | 0.23 |

| Age 3 Social Fear | 68 | 1.33 | 6.00 | 3.69 | 1.11 | −0.13 |

| Age 4 Social Fear | 64 | 1.00 | 6.00 | 3.33 | 1.24 | −2.33* |

| Age 5 Social Fear (Fall) | 81 | 1.00 | 6.17 | 3.44 | 1.36 | −0.42 |

| Age 5 Social Fear (Spring) | 78 | 1.00 | 6.17 | 3.32 | 1.31 | −0.40 |

| Age 2 Nonsocial Fear | 107 | 1.00 | 4.20 | 2.16 | 0.65 | −1.95† |

| Age 3 Nonsocial Fear | 68 | 1.83 | 6.17 | 3.45 | 0.91 | 1.00 |

| Age 4 Nonsocial Fear | 64 | 1.50 | 6.00 | 3.70 | 1.06 | 0.32 |

| Age 5 Nonsocial Fear (Fall) | 81 | 1.17 | 6.67 | 3.73 | 1.18 | −0.36 |

| Age 5 Nonsocial Fear (Spring) | 78 | 1.67 | 6.50 | 3.60 | 1.10 | 0.58 |

| Age 2 Inhibitory Control | 95 | −2.29 | 2.30 | 0.01 | 1.00 | −1.85† |

| Age 2 Observed Social Fear | 110 | 1.00 | 4.50 | 2.57 | 0.89 | 0.11 |

| Age 2 Observed Nonsocial Fear | 110 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 2.85 | 0.91 | −2.25* |

| Age 2 Dysregulated Fear | 111 | −3.31 | 25.04 | 14.12 | 5.59 | 0.40 |

| Age 5 Social Inhibition | 82 | 0.00 | 2.00 | 0.74 | 0.49 | −0.50 |

| Age 5 Anxious Behaviors with Peers | 70 | −1.04 | 5.30 | 0.00 | 1.00 | −0.63 |

Note: t is the result of an independent-samples t-test comparing scores for boys and girls.

p < 0.10,

p < 0.05.

Table 2.

Bivariate Associations

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. | 13. | 14. | 15 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age 2 Social Fear | |||||||||||||||

| 2. Age 3 Social Fear | 0.29* | ||||||||||||||

| 3. Age 4 Social Fear | 0.25* | 0.57** | |||||||||||||

| 4. Age 5 Social Fear (F) | 0.30** | 0.57** | 0.75** | ||||||||||||

| 5. Age 5 Social Fear (S) | 0.30** | 0.57** | 0.75** | 0.82** | |||||||||||

| 6. Age 2 Nonsocial Fear | 0.45** | 0.21† | 0.26* | 0.25* | 0.24* | ||||||||||

| 7. Age 3 Nonsocial Fear | −0.18 | 0.23† | 0.19 | 0.15 | 0.17 | 0.01 | |||||||||

| 8. Age 4 Nonsocial Fear | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.20 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.43** | ||||||||

| 9. Age 5 Nonsocial Fear (F) | 0.24* | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.25* | 0.19† | 0.14 | 0.31* | 0.64** | |||||||

| 10. Age 5 Nonsocial Fear (S) | −0.01 | −0.02 | −0.09 | −0.01 | −0.03 | 0.09 | 0.38** | 0.49** | 0.66** | ||||||

| 11. Inhibitory Control | −0.01 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.06 | −0.07 | −0.25† | −0.14 | −0.25* | |||||

| 12. Observed Social Fear | 0.25** | 0.42** | 0.33** | 0.35** | 0.40** | 0.25** | −0.02 | −0.05 | 0.07 | −0.09 | 0.01 | ||||

| 13. Observed Nonsocial Fear | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.21 | 0.29** | 0.31** | 0.25** | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.03 | −0.16 | 0.02 | 0.16 | |||

| 14. Dysregulated Fear | −0.22* | −0.33** | −0.30* | −0.32** | −0.42** | −0.29** | 0.07 | 0.19 | 0.13 | 0.23* | −0.09 | −0.59** | −0.39** | ||

| 15. Social Inhibition | 0.26* | 0.42** | 0.58** | 0.73** | 0.63** | 0.22* | 0.08 | −0.03 | 0.09 | −0.18 | 0.22† | 0.25* | 0.35** | −0.34** | |

| 16. Anxious Behaviors with Peers | 0.20† | 0.29* | 0.40** | 0.29* | 0.32** | 0.15 | −0.11 | −0.21 | −0.04 | −0.06 | 0.10 | 0.32** | 0.14 | −0.26* | 0.33** |

Note:

p < 0.10,

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01

Independent samples t-tests (Table 1) revealed greater parent-reported social fear for girls (M = 3.76, SD = 1.40) than boys (M = 3.04, SD = 1.04) and greater observed nonsocial fear for girls (M = 3.07, SD = 0.89) than boys (M = 2.69, SD = 0.91) at age 2. Thus, sex was used as a covariate in all regression and ANOVA models.

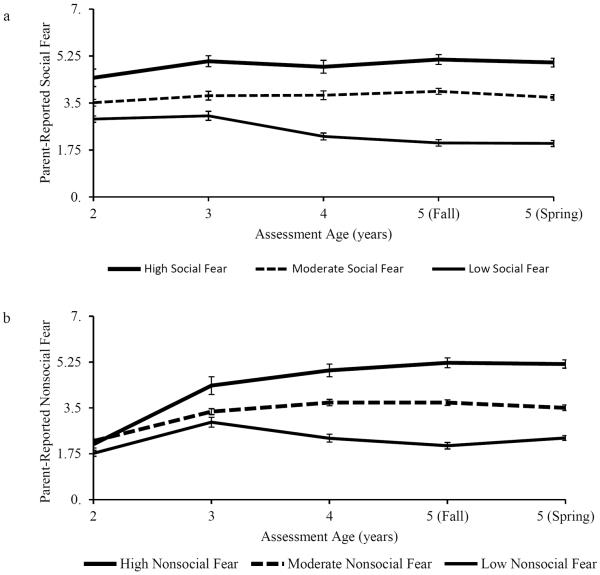

Trajectories of Social Fear in Early Childhood

Comparisons of LCGA models based on parent ratings of social fear suggested that a 3-class model fit the data best (Table 3). The average probability for membership in latent classes was high (M = 0.86). The first class (n = 20) was reported as having high social fear across all assessments (Figure 1a). A second class (n = 52) was reported as having moderate social fear across all assessments. A third class (n = 39) was reported as having low social fear across all assessments. Thus, children were divided into three groups (i.e., high social fear, moderate social fear, or low social fear); each child was placed into the group for which his/her probability of membership was highest. Sex was unrelated to social fear group (χ2[2] = 0.86, p > 0.10).

Table 3.

Fit statistics for latent class growth models

| Classes | AIC | BIC | Entropy | Bootstrapped Ratio Testa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Fear | ||||

| 2 | 1166.80 | 1193.89 | 0.74 | 138.15** |

| 3 | 1132.35 | 1167.58 | 0.71 | 40.45 ** |

| 4 | 1130.56 | 1173.92 | 0.66 | 7.79 |

| Nonsocial Fear | ||||

| 2 | 1118.31 | 1145.41 | 0.55 | 37.76** |

| 3 | 1106.19 | 1141.41 | 0.61 | 18.12 ** |

| 4 | 1109.06 | 1152.41 | 0.66 | 3.130 |

Note: Best-fitting models are bolded.

Parametric Bootstrapped Likelihood Ratio Test for n vs n-1 classes.

p<.01.

Figure 1.

Latent trajectories of (a) social and (b) nonsocial fear from 2 to 5 years of age

To verify the independence of groups, we used a Univariate ANOVA to test for group differences in parent-reported social fear at each assessment. That is, we tested whether groups reflected meaningful differences in parents' original ratings. This test revealed significant differences between groups in parent-reported social fear at ages 2 (F2, 103 = 16.87, p < 0.01, ηp2 = 0.23), 3 (F2, 64 = 24.07, p < 0.01, ηp2 = 0.43), 4 (F2, 60 = 47.98, p < 0.01, ηp2 = 0.62), and in the fall (F2, 77 = 123.50, p < 0.01, ηp2 = 0.76) and spring (F2, 73 = 134.54, p < 0.01, ηp2 = 0.79) of the kindergarten year. Post-hoc tests showed that all three groups differed in social fear at each assessment; the high social fear group was always reported as having the highest levels of social fear and the low social fear group was always reported as having the lowest levels of social fear.

Trajectories of Nonsocial Fear in Early Childhood

The process for deriving the nonsocial fear trajectory groups was identical to that for deriving the social fear groups. Comparisons of LCGA models for nonsocial fear suggested that a 3-class model fit the data best (Table 3). The average estimated probability for membership in latent classes was high (M = 0.85). All classes showed relatively similar levels of nonsocial fear at age 2 (Figure 1b). Over time, steep increases followed by high levels of nonsocial fear across assessments were reported for one of the classes (n = 17). Moderate increases followed by moderate levels of nonsocial fear across assessments were reported for a second class (n = 81). A third class (n = 14) was reported as having low, stable levels of nonsocial fear across all assessments. Thus, children were divided into three groups (i.e., high nonsocial fear, moderate nonsocial fear, low nonsocial fear); each child was placed into the group for which his/her probability of membership was highest. Sex of child was unrelated to nonsocial fear trajectory group (χ2[2] = 0.27, p > 0.10). Nonsocial fear group was also unrelated to social fear group (χ2[4] = 6.84, p > 0.10), suggesting that trajectories did not simply reflect global levels of fear.

Again, we used a Univariate ANOVA to test for group differences in parent-reported nonsocial fear at each assessment to determine whether groupings reflected meaningful differences in parents' original ratings of nonsocial fear. Significant group differences in nonsocial fear were seen at ages 2 (F2, 103 = 3.78, p < 0.01, ηp2 = 0.07), 3 (F2, 64 = 11.70, p < 0.01, ηp2 = 0.27), 4 (F2, 60 = 29.22, p < 0.01, ηp2 = 0.49), and during the fall (F2, 77 = 72.78, p < 0.01, ηp2 = 0.65) and spring (F2, 73 = 63.89, p < 0.01, ηp2 = 0.64) of the kindergarten year. Post-hoc tests showed that at age 2, only the low and moderate groups differed from one another in levels of nonsocial fear, with the moderate group reported as having greater levels of nonsocial fear than the low fear group. At age 3, all comparisons except that between the low and moderate groups were significant; the high fear group was reported as having greater levels of nonsocial fear than the other two groups. At ages 4 and 5, all groups were significantly different from one another in levels of nonsocial fear; the high and low fear groups were reported as having the highest and lowest levels of nonsocial fear, respectively. Thus, consistent with Hypothesis 1, social fear and nonsocial fear appeared to follow distinct developmental trajectories between ages 2 and 5.

Associations between Trajectory Groups and Children's Anxious Behaviors

We then used a Univariate ANOVA to test hypotheses about unique associations between social fear groups, nonsocial fear groups, and our measure of anxious behaviors at age 2. Social fear group was significantly associated with slopes of dysregulated fear (F2, 106 = 6.54, p < 0.01, ηp2 = 0.11). Follow up tests suggested that both the high (t89 = 2.30, p < 0.05, d = 0.50) and moderate (t57 = 3.65, p < 0.01, d = 0.96) social fear groups showed more dysregulated fear than the low social fear group. The high social fear group showed moderately more dysregulated fear than the moderate social fear group (t70 = 1.79, p < 0.10, d = 0.46). Nonsocial fear groups were not associated with slopes of dysregulated fear at age 2 (F2, 106 = 2.19, p > 0.10). Consistent with Hypothesis 2, this pattern of results suggests that a trajectory of high, stable social fear during toddlerhood and preschool was associated with the greatest amount of dysregulated fear.

Next, we used Univariate ANOVAs to test associations between social fear, nonsocial fear, and anxious behaviors at age 5. Anxious behaviors with peers and parent-reported social inhibition were predicted in separate models2. Social fear group significantly predicted anxious behaviors with peers (F2, 66 = 4.52, p < 0.05, ηp2 = 0.12). The high social fear group showed more anxious behaviors with peers than both the low (t37 = −2.75, p < 0.01, d = 0.92) and moderate (t43 = −2.09, p < 0.05, d = 0.62) social fear groups. The low and moderate social fear groups did not differ in the numbers of anxious behaviors displayed with peers (t54 = −0.66, p > 0.10). Nonsocial fear groups were unrelated to anxious behaviors with peers (F2, 66 = 0.68, p > 0.10). Again, consistent with Hypothesis 2, results suggest that a trajectory of high, stable social fear during toddlerhood and preschool was associated with the greater numbers of socially anxious behaviors at age 5.

Social fear trajectory groups also significantly predicted parent reported social inhibition at age 5 (F2, 78 = 29.91, p < 0.05, ηp2 = 0.43). Children in the high social fear group were reported as greater in social inhibition at age 5 relative to both the low (t44 = −7.37, p < 0.01, d = 2.51) and moderate (t50 = −2.49, p < 0.01, d = 83) social fear groups. Children in the moderate social fear group were also reported as showing greater social inhibition at age 5 than children inthe low social fear group (t64 = −5.67, p < 0.01, d = 1.40). Nonsocial fear trajectory groups did not differ in parent-reported social inhibition at age 5 (F2, 78 = 0.04, p > 0.10). Similar to previous findings, these results are consistent with Hypothesis 2, suggesting that high, stable social fear during toddlerhood and preschool predicted the greatest amount of social inhibition at age 5.

Latent Trajectories of Fear, Inhibitory Control, and Anxious Behaviors

In our final set of analyses, we used hierarchical regression models to test the hypothesis that levels of inhibitory control at age 2 moderated links between fear trajectory groups and children's anxious behaviors at age 5. Fear trajectory groupings, rather than continuous fear variables, were included in these analyses given the indication of the LCGA models that heterogeneity in fear and fear processes existed across groups. Analyses focused only on age 5 behaviors, tested as outcomes in separate models, so that all models tested unique longitudinal outcomes. To create a more stringent test of the longitudinal contributions of social and non-social fear to age 5 outcomes, social and non-social fear were tested as simultaneous predictors of child outcomes. A 4-step model was used for each outcome measure: sex of child and age 2 fearfulness were entered into the first step as covariates. Main effects for social fear group (dummy coded; Aiken & West, 1991), nonsocial fear group (dummy coded) and inhibitory control were entered in the second step. The interactions between dummy codes for nonsocial fear groups and inhibitory control were entered in the third step. Interactions between dummy codes for social fear groups and inhibitory control were entered in the fourth step. Interactions between social fear groups and inhibitory control were entered last given hypothesized associations between social fear and inhibitory control for children's outcomes. The interactions between inhibitory control and fear groups were considered significant if a significant change in R2 resulted from the addition of the interaction terms (Step 3 for nonsocial fear, Step 4 for social fear). Moderation analyses are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Simple effects of social and nonsocial fear groups controlling for sex of child, age 2 fear, inhibitory control, and interactions between fear groups and inhibitory control

The change in R2 suggested that nonsocial fear groups and inhibitory control did not interact to predict anxious behaviors with peers (ΔR2 = 0.06, p > 0.05) or parent-reported inhibition (ΔR2 = 0.03, p > 0.05) at age 5. However, a significant change in R2 in the final step of the model predicting socially anxious behaviors with peers suggested an interaction between social fear group and inhibitory control predicting anxious behaviors at age 5 (ΔR2 = 0.10, p < 0.05). Probing this interaction at low (−1 SD) and high (+1 SD) levels of inhibitory control revealed that when levels of inhibitory control were low, neither the low social fear group (B = −0.18, SE(B) = 0.46, p > 0.10) nor the high social fear group (B = −0.11, SE(B) = 0.52, p > 0.10) differed from the moderate fear group in age 5 anxious behaviors with peers. However, when levels of inhibitory control were high at age 2, the high social fear group showed more anxious behaviors with peers at age 5 (B = 2.05, SE(B) = 0.62, p < 0.01) than did the moderate group3. The low and moderate social fear groups did not differ in anxious behaviors with peers at high levels of inhibitory control (B = −0.17, SE(B) = 0.43, p > 0.05).

For the model predicting parent reported social inhibition at age 5, a nonsignificant, change in R2 suggested that neither nonsocial fear group (ΔR2 = 0.00, p > 0.05) nor social fear group (ΔR2 = 0.02, p > 0.05) interacted with inhibitory control to predict childhood social inhibition. Rather, the main-effects only model in Step 2 suggested that social fear groups (High: B = 0.21, SE(B) = 0.12, p < 0.10, Low: B = −0.55, SE(B) = 0.10, p < 0.01) and inhibitory control (B = 0.11, SE(B) = 0.04, p = 0.01) were independent predictors of parent-reported social inhibition at age 5. Similar to the results of the one-way ANOVA, parents reported more social inhibition in the high social fear group and less social inhibition in the low social fear group relative to the moderate group. Similarly, greater inhibitory control at age 2 was associated with greater parent-reported inhibition at age 5. Thus, results were consistent with the expectation that high levels of inhibitory control and high social fear predicted greater numbers of socially anxious behaviors at age 5, although these effects were compounded only for observed behaviors with peers.

Discussion

We addressed three primary aims in the current work. First, we identified trajectories of development for social and nonsocial fear between 2 and 5 years of age. Consistent with the hypotheses that social and nonsocial fear would follow distinct developmental trajectories across toddlerhood and preschool, social and nonsocial fear trajectories were unrelated, underscoring their roles as unique scientific constructs that reflect distinct emotion processes early in life.

Second, we tested whether early trajectories of social and nonsocial fear predicted children's socially anxious behaviors at ages 2 and 5. Greater anxious behaviors, based on criteria for Social Anxiety Disorder, were derived from both observational and parent-report measures. Overall, trajectories of high, stable social fear across preschool and early childhood predicted greater numbers of socially anxious behaviors at both 2 and 5 years of age. Trajectories of nonsocial fear did not predict anxious behaviors, underscoring the importance of distinguishing between social and nonsocial fear development in association with putative risk for social anxiety early in life.

Finally, we tested whether early inhibitory control moderated links between trajectories of fear and socially anxious behaviors at age 5. Social fear and inhibitory control made independent contributions to children's social behaviors at age 5 and interacted to predict behaviors in the laboratory. Children showed greater anxious behaviors with peers when levels of both social fear and inhibitory control were high. Such findings suggest that combined propensities for overcontrol and high levels of social fear may be detrimental. Again, nonsocial fear was unrelated to children's anxious behaviors at age 5.

Distinguishing Trajectories of Social and Nonsocial Fear

Extending previous work dissociating types of fear in children, we found little overlap between developmental trajectories of social and nonsocial fear between 2 and 5 years of age. Social fear groups reflected stable individual differences in severity, rather than shape, of developing social fear. This finding is consistent with previous work that identified four trajectories of social fear between 6 and 36 months of age (Brooker et al., 2013): stable, high social fear; steeply increasing social fear; normative, slowly increasing social fear; and decreasing social fear. Notably, by age 36 months, levels of social fear in the decreasing group were not different from those in the normative group (i.e., slowly increasing social fear). Thus, it is reasonable to expect, given the first age of assessment in the current work, that only three patterns of developing social fear would be visible. Together, these studies suggest that differences in the shape of social fear development may occur during infancy, while differences in social fear during preschool and early childhood are associated largely with severity.

In contrast, preschool and early childhood appear to be an important time for the development of individual differences in nonsocial fear. This was evident in two primary ways. First, levels of nonsocial fear were largely uncorrelated across nonadjacent assessments. This suggests a high degree of change over time, particularly for periods of more than 12 months. Although occasional suggestions arise that temperament traits, such as fear, should always evidence high levels of continuity, leading theorists have long agreed that the expression of temperament evolves dynamically across the life span, with less continuity expected during periods of developmental change (Goldsmith et al., 1987). Notably, the period of developmental change elucidated here was not apparent in prior work, which largely focused on nonsocial fear during the first year of life (Scarr & Salapatek, 1970).

We also found that independence among trajectory groups was not fully achieved until age 4. Research on emerging emotions in infants has suggested that social fear can be reliably elicited earlier than nonsocial fear (Kagan, Kearsley, & Zelazo, 1978). This developmental sequence may be adaptive in that it promotes the development of an attachment relationship and infant safety early in life (Sroufe, 1977). As such, it may be the case that the critical periods of development for social and nonsocial fear are also distinct. While this claim cannot be validated by a single study, our work suggests that this possibility be considered in future research.

Social, but not Nonsocial, Fear Trajectories Predict Children's Socially Anxious Behaviors

High, stable levels of social fear across early childhood were associated with greater dysregulated fear, more anxious behaviors during free play with peers, and more parent-reported social inhibition. No such associations were found for nonsocial fear. Notably, outcome measures were derived through separate data collection methods and included different ages of assessment. Socially anxious behaviors were selected as developmentally-appropriate correlates of diagnostic criteria for Social Anxiety Disorder, which has shown the most robust associations with early fearfulness. Accordingly, dysregulated fear, anxious behaviors during early peer play, and greater parent-reported social inhibition have each been linked to an increased risk for Social Anxiety Disorder (Buss, 2011; Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2009; Coplan et al., 1994). Importantly, despite some evidence for elevated symptoms (Buss et al., 2013), children in the current study are quite young and largely without clinical diagnoses. Thus, our findings suggest that differentiating levels of early social and nonsocial fear may help to refine predictions of risk rather than identify the presence of clinical symptoms. This, of course, is preferable given our larger goal of informing programs of targeted prevention and intervention.

We also note that a substantial proportion of children were classified as low in social or nonsocial fear over time. These children showed the lowest levels of dysregulated fear at age 2 and parent-reported inhibition at age 5. Although this suggests minimal levels of anxiety risk in low-fear children, our data do not offer insight about other developmental outcomes for these children. For example, low levels of fear have been associated with greater early risk for externalizing problems (Colder, Mott, & Berman, 2002). Investigating putative outcomes associated with low levels of fearfulness may be an important avenue for future research.

Additionally, it will be important to understand how additional distinctions between social and nonsocial fear can help to refine current measures of fear. As previously mentioned, literatures on both behavioral inhibition and dysregulated fear have largely composited social and nonsocial fear measures to produce a single outcome measure. Our findings, along with previous work (Dyson et al., 2011), raise the possibility that slopes of dysregulated fear produced by measures of fear in only social contexts would differ from dysregulated fear assessed in only nonsocial contexts. More importantly, our results suggest that slopes of dysregulated fear in social contexts may be of greater consequence for the development of social anxiety over time. Thus, this is another potentially important avenue for future research.

Inhibitory Control Moderates Links between Social Fear and Anxious Behaviors

We found that inhibitory control moderated associations between trajectories of social fear and anxious behaviors at age 5. Greater inhibitory control at age 2 predicted more anxious behaviors with peers at age 5 when coupled with stable, high levels of social fear. Unexpectedly, moderation was not observed for parent-reported anxious behaviors. Although a small correlation was present between parent-reported inhibition and observed anxious behaviors during kindergarten, these constructs are clearly non-redundant. Parental reports of child behavior may reflect broader characterizations of children's behaviors relative to observational measures (Seifer, Sameroff, Barrett, & Krafchuk, 1994). It is possible that our laboratory assessment highlights the difficulty that high fear children have initiating interaction with new groups of peers rather than an overall absence of peer relationships. Indeed, although fearful preschoolers are generally less likely to engage in social activities, parents do report engagement in structured, dyadic play with a single friend (Coplan, DeBow, Schneider, & Graham, 2009).

Our findings lend support to prior assertions that the nature and context in which control is exerted is important for child outcomes (Cole et al., 1994; Eisenberg, Smith, Sadovsky, & Spinrad, 2004). Optimal outcomes appear to rely on the flexible modulation of emotion and behavior across contexts in a way that balances highly-restricted and highly impulsive behaviors (Bonanno & Burton, 2013; Ryan & Deci, 2006). Our work extends theoretical distinctions by suggesting that when more “automatic” tendencies for over-control are coupled with stable, high levels of fear, risk for internalizing problems is compounded in young children. An important implication of this is that interventions targeted at enhancing self-control may be detrimental, rather than helpful, for highly fearful children. This idea has been noted previously (Moffitt et al., 2011), but is infrequently discussed.

Limitations

Despite its contributions, the current study is not without limitations. Profiles of early social and nonsocial fear development were based on parent-report questionnaires. Given that, as previously asserted, parental-report measures may not fully correspond to observed behaviors, analyses conducted with observational data may suggest somewhat different trajectories of fear development. Discrepancies due to differences in measurement and their implications for child outcomes will be important to determine in future research.

Similarly, analyses are based on a moderately-sized sample. Developmental scientists continue to balance conducting multi-trait, multi-method assessments in smaller samples with collecting less-intensive approaches in larger samples. Clearly, our work prioritizes the former approach. Concerns about sample size can be at least partially subdued by the use of multiple fit indices to determine the correct LCGA model. At least one study has reported that as sample sizes approach 100 participants, such as in ours, the likelihood of correctly selecting a 3 versus 2 class model ranges from 80% to 91% for individual indices. Moreover, simulations suggest that small sample sizes more frequently contribute to the selection of too few rather than too many classes (Yang, 2006). Thus, although we maintain confidence in the latent classes reported here, it is possible that smaller classes exist in the population that have not yet been identified.

In addition, the current sample is one of low risk for psychopathology, and the current work does not include clinical outcomes for the children described as putatively at risk according to levels of fear and inhibition. Initial diagnoses of Social Anxiety Disorder tend to occur during adolescence (Burke, Burke, Regier, & Rae, 1990), making it difficult to predict the proportion of children in the current sample who will develop disorder. As such, the degree to which the current results generalize to high-risk individuals is unknown.

Finally, the measures in the current study differ somewhat from the work by Dyson and colleagues (2011). Although such discrepancies are occasionally viewed unfavorably, we view this as a strength of the current work. The agreement across both sets of findings regarding social fear provide a conceptual replication without reliance on specific measures and assessments.

Conclusions

In sum, levels of social fear uniquely predicted individual differences in children's socially anxious behaviors measured via observations and parent report across a three-year period. Moreover, social fear, but not nonsocial fear, interacted with early inhibitory control to predict socially anxious behaviors, such that trajectories of high social fear coupled with greater inhibitory control appeared to put children at greatest risk for anxious behaviors by age 5. While additional work is needed, our results suggest that measures that distinguish social fear from other types of fear will be most useful for identifying children who are at high risk for developing problems with social anxiety. These findings expand on theoretical and empirical work that elucidates trajectories of early risk and move us closer to identifying specific profiles of risk for anxiety problems in young children.

Acknowledgments

Data collection for this project was supported by R03 MH67797 and R01 MH75750 from the National Institute of Mental Health (PI: Buss). The writing of this manuscript was supported by K01 MH100240 from the National Institute of Mental Health (PI: Brooker) and R15 HD076158 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (PI: Kiel). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

We thank the families who devoted their time to participating in this study and the staff members of the Emotion Development Lab who helped with the recruitment of study participants and data collection.

Footnotes

Additional concerns about measures are further alleviated by the fact that not all trajectory groups showed change from age 2 to age 3, when the TBAQ was replaced by the CBQ.

Results are identical if age 5 outcomes are included together in a MANOVA.

Identical results were seen at mean and high levels of inhibitory control, suggesting that effects were linear.

References

- Biederman J, Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Rosenbaum JF, Herot C, Friedman D, Snidman N, Faraone SV. Further evidence of association between behavioral inhibition and social anxiety in children. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158(10):1673–1679. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.10.1673. http://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.158.10.1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Burton CL. Regulatory flexibility: An individual differences perspective on coping and emotion regulation. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2013;8(6):591–612. doi: 10.1177/1745691613504116. http://doi.org/10.1177/1745691613504116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronson G. The hierarchical organization of the central nervous system: Implications for learning processes and critical periods in early development. Behavioral Science. 1965;10(1):7–25. doi: 10.1002/bs.3830100103. http://doi.org/10.1002/bs.3830100103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooker RJ, Buss KA. Toddler Fearfulness Is Linked to Individual Differences in Error-Related Negativity During Preschool. Developmental Neuropsychology. 2014;39(1):1–8. doi: 10.1080/87565641.2013.826661. http://doi.org/10.1080/87565641.2013.826661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooker RJ, Buss KA, Lemery-Chalfant K, Aksan N, Davidson RJ, Goldsmith HH. The development of stranger fear in infancy and toddlerhood: normative development, individual differences, antecedents, and outcomes. Developmental Science. 2013;16(6):864–878. doi: 10.1111/desc.12058. http://doi.org/10.1111/desc.12058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooker RJ, Neiderhiser JM, Kiel EJ, Leve LD, Shaw DS, Reiss D. The Association Between Infants' Attention Control and Social Inhibition is Moderated by Genetic and Environmental Risk for Anxiety. Infancy. 2011;16(5):490–507. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7078.2011.00068.x. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7078.2011.00068.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss KA. Which fearful toddlers should we worry about? Context, fear regulation, and anxiety risk. Developmental Psychology. 2011;47(3):804–819. doi: 10.1037/a0023227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss KA, Goldsmith HH. Manual and normative data for the Laboratory Temperament Assessment Battery - Toddler Version. University of Wisconsin-Madison, Department of Psychology; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Buss KA, Kiel EJ, Morales S, Robinson E. Toddler Inhibitory Control, Bold Response to Novelty, and Positive Affect Predict Externalizing Symptoms in Kindergarten. Social Development. 2014;23(2):232–249a. doi: 10.1111/sode.12058. http://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chronis-Tuscano A, Degnan KA, Pine DS, Perez-Edgar K, Henderson HA, Diaz Y, Fox NA. Stable early maternal report of behavioral inhibition predicts lifetime social anxiety disorder in adolescence. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;48(9):928–935. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181ae09df. http://doi.org/10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181ae09df. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clauss JA, Blackford JU. Behavioral inhibition and risk for developing social anxiety disorder: A meta-analytic study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2012;51(10):1066–1075.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.08.002. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colder CR, Mott JA, Berman AS. The interactive effects of infant activity level and fear on growth trajectories of early childhood behavior problems. Development and Psychopathology. 2002;14(01):1–23. doi: 10.1017/s0954579402001013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM, Michel MK, Teti LO. The Development of Emotion Regulation and Dysregulation: A Clinical Perspective. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1994;59(2–3):73–102. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5834.1994.tb01278.x. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coplan RJ, DeBow A, Schneider BH, Graham AA. The social behaviours of inhibited children in and out of preschool. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2009;27(4):891–905. doi: 10.1348/026151008x396153. http://doi.org/10.1348/026151008X396153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coplan RJ, Rubin KH, Fox NA, Calkins SD, Stewart SL. Being Alone, Playing Alone, and Acting Alone: Distinguishing among Reticence and Passive and Active Solitude in Young Children. Child Development. 1994;65(1):129–137. http://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.ep9406130684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Côté S, Tremblay RE, Nagin D, Zoccolillo M, Vitaro F. The development of impulsivity, fearfulness, and helpfulness during childhood: patterns of consistency and change in the trajectories of boys and girls. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2002;43(5):609–618. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00050. http://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diagnostic and staitistical manual of mental disorders. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dyson MW, Klein DN, Olino TM, Dougherty LR, Durbin CE. Social and Non-Social Behavioral Inhibition in Preschool-Age Children: Differential Associations with Parent-Reports of Temperament and Anxiety. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 2011;42(4):390–405. doi: 10.1007/s10578-011-0225-6. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-011-0225-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, Spinrad TL, Fabes RA, Shepard SA, Reiser M, Guthrie IK. The Relations of Regulation and Emotionality to Children's Externalizing and Internalizing Problem Behavior. Child Development. 2001;72(4):1112–1134. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00337. http://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Murphy B, Maszk P, Smith M, Karbon M. The Role of Emotionality and Regulation in Children's Social Functioning: A Longitudinal Study. Child Development. 1995;66(5):1360–1384. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00940.x. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Smith CA, Sadovsky A, Spinrad TL. Effortful control: Relations with emotion regulation, adjustment, and socialization in childhood. In: Baumeister RF, Vohs KD, editors. Handbook of self-regulation: Research, theory, and applications. The Guilford Press; New York, New York: 2004. pp. 259–282. [Google Scholar]

- Emde R, Gaensbauer T, Harmon R. Emotional expression in infancy: A bbiobehavioral study. International University Press; New Y: 1976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essex M, Boyce WT, Goldstein LH, Armstrong JM, Kraemer H, Kupfer DJ, The MacArthur Assessment Battery Working Group The Confluence of mental, physical, social, and academic difficulties in middle childhood. II: Developing the MacArthur Health and Behavior Questionnaire. Journal of the American Academy of Child. 2002;41(5):588–603. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200205000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox NA, Henderson HA, Rubin KH, Calkins SD, Schmidt LA. Continuity and Discontinuity of Behavioral Inhibition and Exuberance: Psychophysiological and Behavioral Influences across the First Four Years of Life. Child Development. 2001;72(1):1–21. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00262. http://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gartstein MA, Bridgett DJ, Rothbart MK, Robertson C, Iddins E, Ramsay K, Schlect S. A latent growth examination of fear development in infancy: Contributions of maternal depression and the risk for toddler anxiety. Developmental Psychology. 2010;46(3):651–668. doi: 10.1037/a0018898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith HH. Studying temperament via construction of the Toddler Behavior Assessment Questionnaire. Child Development. 1996;67(1):218–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith HH, Buss AH, Plomin R, Rothbart MK, Thomas A, Chess S, McCall RB. Roundtable: What Is Temperament? Four Approaches. Child Development. 1987;58(2):505–529. http://doi.org/10.2307/1130527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith HH, Buss KA, Lemery KS. Toddler and childhood temperament: Expanded content, stronger genetic evidence, new evidence for the importance of environment. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33(6):891–905. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.6.891. http://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.33.6.891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebb DO. On the nature of fear. Psychological Review. 1946;53(5):259–276. doi: 10.1037/h0061690. http://doi.org/10.1037/h0061690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess EH. Two conditions limiting the critical age for imprinting. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology. 1959;52(5):515–518. doi: 10.1037/h0049164. http://doi.org/10.1037/h0049164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Biederman J, Henin A, Faraone SV, Davis S, Harrington K, Rosen JF. Behavioral inhibition in preschool children at risk is a specific predictor of middle childhood social anxiety: A five-year follow-up. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics. 2007;28(3):225–233. doi: 10.1097/01.DBP.0000268559.34463.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirshfeld DR, Rosenbaum JF, Biederman J, Bolduc EA, Faraone SV, Snidman N, Kagan J. Stable behavioral inhibition and its association with anxiety disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1992;31(1):103–111. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199201000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izard CE, Dougherty LM, Hembree EA. A system for identifying affect expressions by holistic judgments (AFFEX) Instructional Resources Center, University of Delaware; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Kagan J, Kearsley RB, Zelazo P. Infancy: Its place in human development. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan TB, Rottenberg J. Psychological flexibility as a fundamental aspect of health. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30(7):865–878. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.001. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiel EJ, Buss KA. Toddlers' Duration of Attention Toward Putative Threat. Infancy. 2011;16(2):198–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7078.2010.00036.x. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7078.2010.00036.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Zerr AA. Informed theory and measurement equivalence in child development research. Child Development Perspectives. 2010;4(1):25–30. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-8606.2009.00112.x. [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Knaack A. Effortful Control as a Personality Characteristic of Young Children: Antecedents, Correlates, and Consequences. Journal of Personality. 2003;71(6):1087–1112. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.7106008. http://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6494.7106008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Murray K, Harlan ET. Effortful control in early childhood: Continuity and change, antecedents, and implications for social development. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36(2):220–232. http://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.36.2.220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Murray K, Jacques TY, Koenig AL, Vandegeest KA. Inhibitory Control in Young Children and Its Role in Emerging Internalization. Child Development. 1996;67(2):490–507. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1996.tb01747.x. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE, Arseneault L, Belsky D, Dickson N, Hancox RJ, Harrington H, Caspi A. A gradient of childhood self-control predicts health, wealth, and public safety. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2011;108(7):2693–2698. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010076108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray K, Kochanska G. Effortful Control: Factor Structure and Relation to Externalizing and Internalizing Behaviors. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;30(5):503–514. doi: 10.1023/a:1019821031523. http://doi.org/10.1023/A:1019821031523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigg JT. On inhibition/disinhibition in developmental psychology: Views from cognitive and personality psychology and a working inhibition taxonomy. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126(2):220–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.220. http://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner MI, Rothbart MK. Attention, self-regulation and consciousness. Philosopical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B. 1998;353:1915–1927. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1998.0344. http://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.1998.0344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Ahadi SA. Temperament and the development of personality. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1994;103(1):55–68. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.103.1.55. http://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.103.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Ahadi SA, Hershey KL, Fisher P. Investigations of temperament at three to seven years: The Children's Behavior Questionnaire. Child Development. 2001;72(5):1394–1408. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00355. http://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Bates JA. Temperament. In: Eisenberg N, editor. Handbook of child psychology. 5th ed. Vol. 3. Wiley; New York: 1998. pp. 105–176. Vol. Social, emotional, and personality development. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Bates JE. Temperament in children's development. In: Eisenberg N, editor. Handbook of child psychology: Vol 3. Social, emotional, and personality development. 6th ed Wiley; New hyork: 2006. pp. 99–166. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Asendorpf JB. Social withdrawal, inhibition, and shyness in childhood: Conceptual and definitional issues. In: Rubin KH, Asendorpf JB, editors. Social withdrawal, inhibition, and shyness in childhood. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; New York: 1993. pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-Regulation and the Problem of Human Autonomy: Does Psychology Need Choice, Self-Determination, and Will? Journal of Personality. 2006;74(6):1557–1586. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2006.00420.x. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2006.00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM, La Guardia JG, Solky-Butzel J, Chirkov V, Kim Y. On the interpersonal regulation of emotions: Emotional reliance across gender, relationships, and cultures. Personal Relationships. 2005;12(1):145–163. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1350-4126.2005.00106.x. [Google Scholar]

- Saarni C. An Observational Study of Children's Attempts to Monitor Their Expressive Behavior. Child Development. 1984;55(4):1504–1513. http://doi.org/10.2307/1130020. [Google Scholar]