Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

The main objective of this study was to investigate whether maternal adiponectin regulates fetal growth through the endocrine system in the fetal compartment.

Methods

Adiponectin knockout (Adipoq−/−) mice and in vivo adenovirus-mediated reconstitution were used to study the regulatory effect of maternal adiponectin on fetal growth. Primary human trophoblast cells were treated with adiponectin and a specific peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα) agonist or antagonist to study the underlying mechanism through which adiponectin regulates fetal growth.

Results

The body weight of fetuses from Adipoq−/− dams was significantly greater than that of wild-type dams at both embryonic day (E)14.5 and E18.5. Adenoviral vector-mediated maternal adiponectin reconstitution attenuated the increased fetal body weight induced by maternal adiponectin deficiency. Significantly increased blood glucose, triacylglycerol and NEFA levels were observed in Adipoq−/− dams, suggesting that nutrient supply contributes to maternal adiponectin-regulated fetal growth. Although fetal blood IGF-1 concentrations were comparable in fetuses from Adipoq−/− and wild-type dams, remarkably low levels of IGF-binding protein 1 (IGFBP-1) were observed in the serum of fetuses from Adipoq−/− dams. IGFBP-1 was identified in the trophoblast cells of human and mouse placentas. Maternal fasting robustly increased IGFBP-1 levels in mouse placentas, while reducing fetal weight. Significantly low IGFBP-1 levels were found in placentas of Adipoq−/− dams. Adiponectin treatment increased IGFBP-1 levels in primary cultured human trophoblast cells, while the PPARα antagonist, MK886, abolished this stimulatory effect.

Conclusions/interpretation

These results indicate that, in addition to nutrient supply, maternal adiponectin inhibits fetal growth by increasing IGFBP-1 expression in trophoblast cells.

Keywords: Adiponectin, Fetus, Growth, IGF-binding protein, Placenta

Introduction

Obesity is an important risk factor of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular diseases. Despite efforts to fight obesity in the last decade, the prevalence of adult obesity in the USA is still increasing [1]. Results from recent epidemiological studies have indicated that the origins of obesity can be traced to intrauterine fetal development and growth [2]. A new paradigm for the gestational origins of obesity is based on the strong association of a high prevalence of obesity and metabolic defects in later life with high or low birthweight [3–5]. Birthweight is a key marker of fetal growth and is routinely measured. Therefore, elucidating how fetal growth is controlled by the intrauterine metabolic environment will provide mechanistic insight into the gestational origins of obesity.

Nutrient supply is essential for fetal growth. However, the importance of the hormonal system in regulating fetal growth is also well documented [2, 4, 6]. Studies have demonstrated that the fetal IGF system plays a central role in regulating fetal growth [7, 8]. Severe intrauterine and postnatal growth retardation were observed in individuals with an IGF1 mutation and in Igf1 or Igf2 knockout mice [8–12]. Unlike in adults, IGF expression in the fetal compartment is not controlled by growth hormone [7]. IGF-1 is expressed in several fetal tissues, where it stimulates cell growth through endocrine and paracrine effects. IGF-2 is mainly expressed in trophoblast cells, where it enhances fetal growth by promoting placental growth and nutrient transport via autocrine and/or paracrine pathways [8]. Therefore, IGF-1 is the main circulating hormone affecting fetal growth. A family of six IGF-binding proteins (IGFBPs) serves as carriers of IGF-1 in the circulation. Due to their high affinity for IGF, IGFBPs also control the activity of IGFs by modulating their bioavailability. During pregnancy, IGFBP-1 is the predominant binding protein for IGFs in the fetal circulation [13–15]. Fetal blood IGFBP-1 levels inversely correlate with birthweight [14, 16]. Maternal overexpression of Igfbp1 inhibits mouse and rat fetal growth [13, 17–19]. Interestingly, although IGFs play an important role in intrauterine growth restriction and development of obesity in later life induced by maternal nutrient deficiency [7, 20], it is unknown whether the IGF system is involved in altered fetal growth resulting from maternal obesity.

Adiponectin is an adipocyte-secreted hormone that plays an important role in glucose and lipid metabolism [21]. Some human studies have found that maternal blood adiponectin levels are inversely correlated with offspring birthweight [22, 23]. In line with these correlative studies, the Jansson and Powell group showed that infusing full-length recombinant adiponectin to increase maternal adiponectin inhibits fetal growth in mice [24].However, endogenous adiponectin forms multimers and maternal adiponectin is significantly reduced during late normal gestation [23, 25]. Furthermore, the correlation between maternal adiponectin level and birthweight was not identified in studies of pregnant women with and without gestational diabetes [26, 27]. Therefore, it is necessary to use other experimental systems to verify the regulatory effect of maternal adiponectin on fetal growth. In addition, it is not clear whether maternal adiponectin regulates fetal growth through the endocrine system in the fetal compartment.

Methods

Materials

Glucose oxidase/Peroxidase (PGO), WY14643, DNase I, collagenase, Percoll and Fao hepatoma cells were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). Fao cells were derived from a rat hepatoma and no contamination was present. MK886 was obtained from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Rabbit anti-p-IGF-1Rβ and rabbit anti-IGF-1Rβ antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA, USA). Rabbit anti-glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and HRP-linked secondary antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Goat anti-IGFBP-1 and the mouse anti-IGF-1 (total) Luminex kit were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA). The mouse diabetes multiplex assay kit was obtained from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA, USA). NEFA and triacylglycerol (TG) assay kits ware purchased from Wako Diagnostics (Richmond, VA, USA). FBS, NuPAGE gels, SuperScript III reverse transcriptase, Trizol, trypsin and the oligo(dT)12–18 primer were obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Rabbit serum and diaminobenzidine were obtained from Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, CA, USA). All antibodies were validated by their manufacturers.

Experimental animals

Adiponectin knockout (Adipoq−/−) mice were from a C57BL/6 background [28]. C57BL/6 mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). Ten- to 12 week-old nulliparous female mice were randomly assigned for mating. Adipoq−/− and wild-type (WT) mice were cross mated (Fig. 1a); the point at which pregnancy was indicated by the presence of a vaginal plug was assigned embryonic day (E)0.5. To reconstitute adiponectin, 1 × 109 plaque-forming units of purified adenoviral vectors encoding adiponectin or green fluorescent protein (GFP) (named Ad-Adipoq and Ad-gfp, respectively) were injected into Adipoq−/− dams through the tail vein at E15.5 [29]. Placentas and fetuses were collected via Caesarean section at E14.5 or E18.5. Pregnant C57BL/6 mice were fasted overnight (~14 h) and fetal tissue samples were collected at E18.5. All mouse experiments were carried out under Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care guidelines with approval from the University of California San Diego Animal Care and Use Committee. Blood glucose levels were determined using the glucose oxidase/peroxidase method with a standard curve, following manufacturer’s instruction. Blood TG and NEFA concentrations were measured using kits from Wako, following manufacturer’s instructions. Blood IGF-1 and insulin levels were determined using Luminex assay kits, as per manufacturers’ instruction. Mouse body composition was measured by Echo-MRI (Houston, TX, USA). Fetal blood insulin was measured using a mouse diabetes multiplex assay kit.

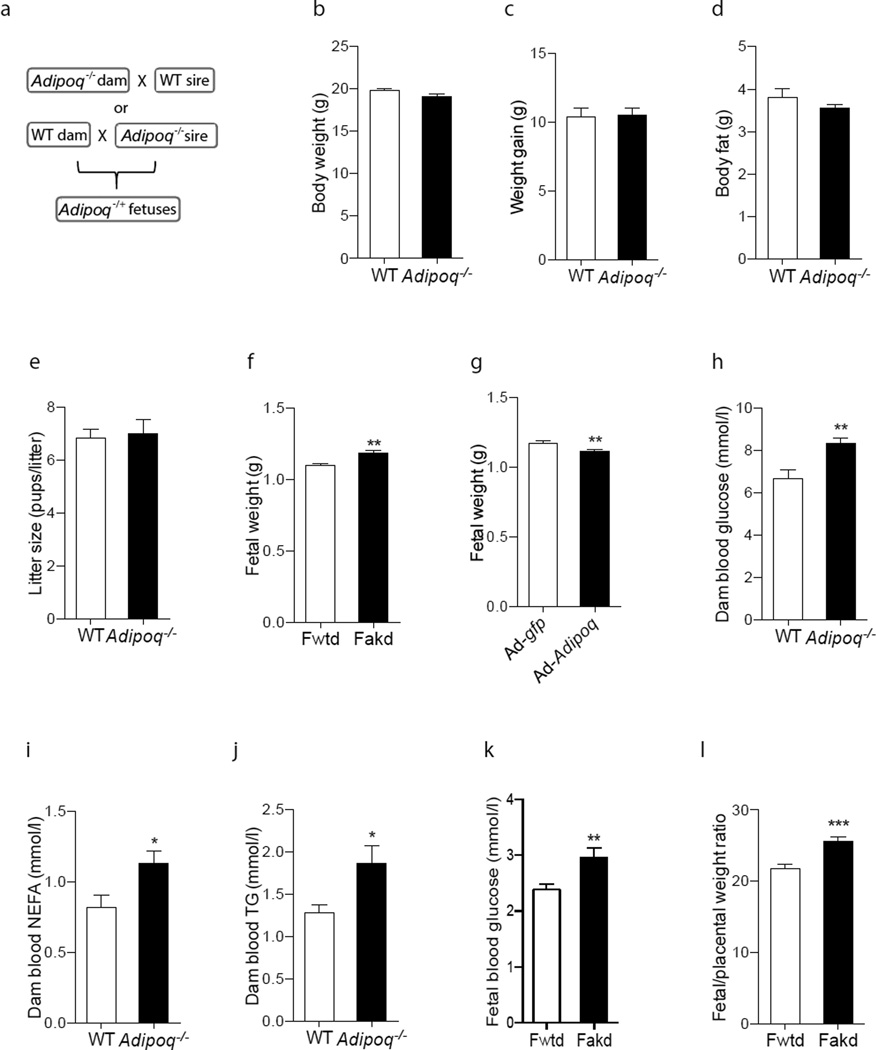

Fig. 1.

Effects of maternal adiponectin on fetal body weight. (a) Schematic diagram showing the production of Adipoq−/+ fetuses. For this, 10–12 week-old nulliparous Adipoq−/− and WT female mice were mated with WT or Adipoq−/− male mice. (b) Maternal body weight. (c) Gestational weight gain was calculated by the difference in body weight between E0.5 and E18.5 (with pups). (d) Maternal body fat, (e) litter size and (f) fetal body weight were determined after removal of fetuses through Caesarean section at E18.5. (g) At E15, Adipoq−/− dams (n=6) were transduced with purified Ad-gfp or Ad-Adipoq through tail vein injection. Fetal samples were collected and weighed at E18.5. (h,k) Blood glucose, (i) NEFA and (j) TG levels were measured using glucose oxidase or assay kits. (l) Fetal:placental weight ratios were calculated using samples at E18.5. (b, d) Maternal body composition was determined by EchoMRI. (b–e, h–j) n=8–10; (f, g, l) n=45–72; (k) n=12. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001

Human primary trophoblast cell culture

Healthy term human placentas were obtained from the University of California San Diego (UCSD) Perinatal Biobank for use in a UCSD Institutional Review Board approved protocol. All patients gave informed consent for the collection and use of placental tissue. Villous tissue was used for isolating trophoblast cells using a three-enzyme digestion and a Percoll gradient approach, as previously described [30]. Briefly, chorionic villi were minced, washed in PBS, and subjected to three sequential digestions: Digestion I: 300 U/ml DNase I, 150 U/ml collagenase and 50 U/ml hyaluronidase (Stemcell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada); Digestions II and III: 0.25% trypsin (wt/vol.) and 300 U/ml DNase I. The pelleted cells from the second and third digests were pooled and resuspended in HBSS, and separated on a Percoll gradient. Purified primary trophoblast cells were seeded on 6-well culture plates overnight in Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium containing 10% (vol./vol.) FBS. After culture for 24 h, cells were treated with the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα) agonist WY14643 or the PPARα antagonist MK886, for 12 h. For adiponectin treatment, a Fao hepatoma cell and primary trophoblast co-culture system was used [31]. Fao cells were transduced with adenoviral vectors in insert wells for 12 h to induce Adipoq expression and adiponectin secretion. After co-culture, protein and mRNA were extracted from the primary trophoblast cells.

Plasmid constructs and generation of adenovirus vectors

Adenoviruses encoding mouse adiponectin or GFP were constructed using the pAd/CMV/V5-Dest vector (Invitrogen). Construction and purification of the viral vectors were carried out as previously described [32].

Immunohistochemistry

Human and mouse placenta biopsy samples were fixed in 10% (vol./vol.) neutral-buffered formalin, processed and paraffin embedded. After washing, samples were heated in 0.1 mol, pH 6.0 citrate buffer for 15 min at 95°C to induce antigen retrieval. They were further blocked with 2% (vol./vol.) normal rabbit serum with 1% (wt/vol.) BSA in PBS for 2 h in a humid chamber at room temperature (RT). Sections were incubated with 10 µg/ml anti-IGFBP-1 primary antibody or rabbit serum (negative control) overnight at 4°C. After washing, samples were overlaid with 1 µg/ml biotinylated rabbit anti-goat antibody (KPL, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) for 2 h at RT and then treated with an immunoperoxidase system for 1 h at RT. Sections were visualised by incubation with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine at RT for 1.5 min and counterstained with haematoxylin (Richard-Allan Scientific, Kalamazoo, MI, USA).

Western blotting and quantitative real-time PCR

Protein samples were extracted from placentas, livers or cultured cells and were separated by SDS-PAGE (using NuPAGE gels). After blotting, proteins were detected with anti-IGFBP1, anti-IGF-1Rβ, anti-p-IGF-1Rβ and anti-GAPDH antibodies (most at 1:1000 dilution; see figure legends). Protein bands were quantified using Quantity One software (Bio-Rad).

Total RNA was prepared from tissues or cells using Trizol, and cDNA was synthesised using SuperScript III reverse transcriptase and oligo(dT)12–18 primer. Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) was performed using an Mx3000p Real-Time PCR system (Stratagene, San Diego, CA, USA) with specific primers for Igf-2Igf-2R and Igfbp1 (see electronic supplementary material [ESM] Table 1). Gene expression was normalised to 18S rRNA levels.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as means ± SEM. Statistical analyses were performed using Student’s t tests or ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni post hoc testing using GraphPad Prism 6 (La Jolla, CA, USA). Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

Results

Maternal adiponectin inhibits fetal growth

Adiponectin cannot pass through the placental barrier [33]. We mated WT dams with Adipoq−/− sires or Adipoq−/− dams with WT sires (Fig. 1a). All fetuses were therefore Adipoq−/+. Pregravid body weights were similar in Adipoq−/− and WT dams (Fig. 1b). During pregnancy, all dams gained a similar amount of weight (Fig. 1c) and had comparable body fat at E18.5 (Fig. 1d). Litter sizes were similar in Adipoq−/− and WT dams (Fig. 1e). Body weight was significantly higher in fetuses from Adipoq−/− dams (Fakd) than in fetuses from WT dams (Fwtd) at both E14.5 (data not shown) and E18.5 (Fig. 1f). We used adenoviral vector-mediated in vivo gene transduction to reconstitute maternal adiponectin in Adipoq−/− dams [34]. Similar to in non-pregnant mice [34], adiponectin protein levels at 3 days after Ad-Adipoq viral vector injection were significantly increased in dam’s blood (data not shown). Our results showed that the body weight was significantly lower in fetuses from adiponectin-reconstituted dams compared with the fetuses from Ad-gfp-treated Adipoq−/− dams (Fig. 1g). Together, these data demonstrate that maternal adiponectin inhibits fetal growth.

Nutrient supply is essential for fetal growth

Interestingly, blood glucose, NEFA and TG concentrations in Adipoq−/− dams were significantly higher than in WT dams (Fig. 1h–j). Our results also showed that fetal blood glucose (Fig. 1k), but not TG and NEFA (data not shown), was significantly increased in fetuses of Adipoq−/− dams. In contrast, adiponectin reconstitution robustly decreased maternal blood glucose, TG and NEFA concentrations and fetal blood glucose levels (ESM Fig. 1). These data indicate that adiponectin plays an important role in maintaining maternal energy homeostasis. Since maternal metabolism directly affects fetal nutrient supply, these results also lead us to postulate that reducing the fetal nutrient supply might be one of the underlying mechanisms through which maternal adiponectin inhibits fetal growth. In line with this hypothesis, the fetal/placental weight ratio, which represents placental nutrient transport efficiency, was significantly increased in Fakd (Fig. 1l). A separate project is underway to investigate how adiponectin regulates maternal metabolism and the role of placental nutrient supply in fetal growth regulation by maternal adiponectin.

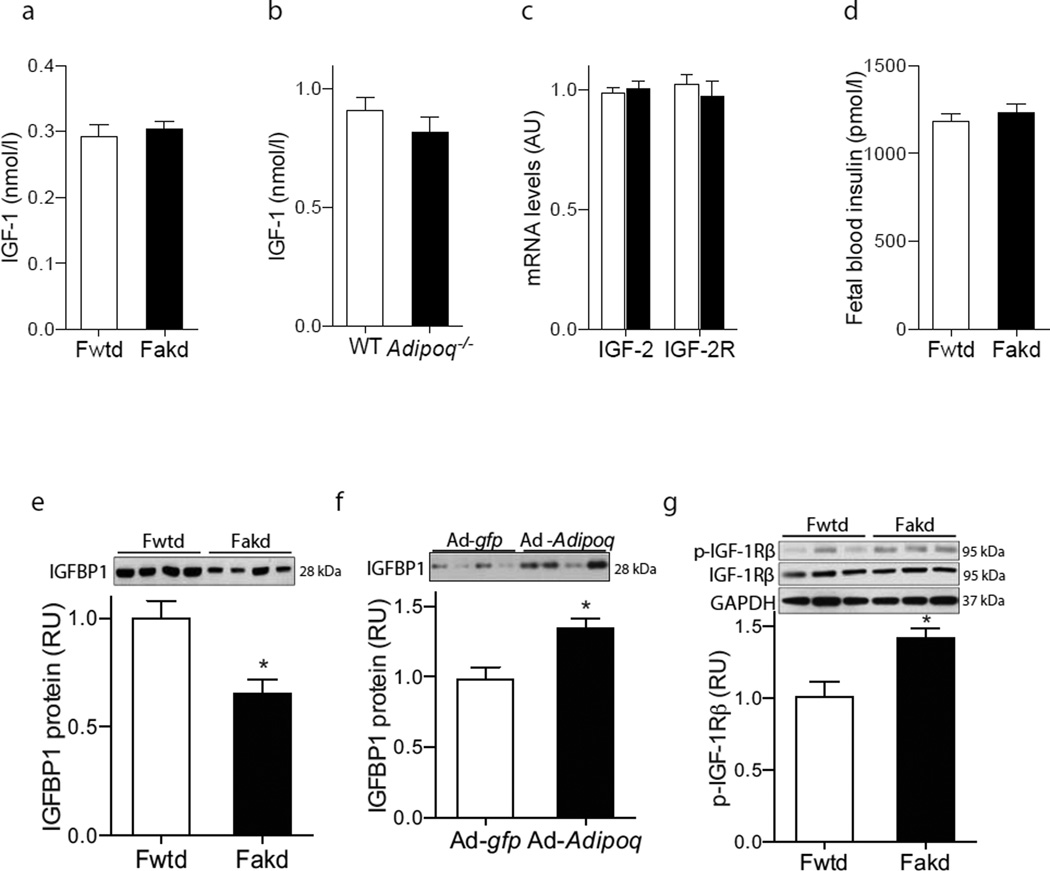

Adiponectin increases fetal blood IGFBP-1 protein levels

The fetal IGF system plays a central role in fetal growth [7, 8]. We measured blood total IGF-1 protein concentrations in both fetuses and dams, and levels of IGF-2 and its receptor in placentas from the cross-breeding studies described above. There was no significant difference in the total IGF-1 concentration of either fetal or maternal blood (Fig. 2a,b). Igf-2 and Igf-2 receptor (Igf-2R) mRNA levels in placentas were similar in Fakd and Fwtd (Fig. 2c). These results suggest that maternal adiponectin deficiency has no significant effect on fetal blood IGF-1 concentration or placental IGF-2 expression. Insulin is another hormone that regulates fetal growth [35]. However, despite increases in fetal blood glucose (Fig. 1k), no significant alteration in the fetal blood insulin concentration was detected in Fakd (Fig. 2d), which may be due to the lack of response by fetal beta cells to glucose [35].

Fig. 2.

Maternal adiponectin has no effect on blood IGF-1 concentration but increases IGFBP-1 protein levels in fetal blood. (a, b) Blood total IGF-1 concentrations were analysed in (a) fetuses (n=12) and (b) dams (n=8). (c) mRNA levels of Igf2 and Igf2r were determined using qPCR with a relative quantification assay (white bar, Fwtd; filled bar, Fakd). (d) Fetal blood insulin was measured using a mouse diabetes multiplex assay kit (n=12). (e, f) IGFBP-1 protein levels in fetal serum samples from Adipoq−/− or adiponectin-reconstituted and control dams (n=12) were measured by western blotting with specific antibodies. (g) Levels of phosphorylated or total IGF-1Rβ protein were determined in fetal livers at E18.5 (n=6) by western blotting. RU, relative units. *p<0.05

IGF-1 bioactivity is also tightly controlled by IGFBP-1 in fetuses [13–15]. A remarkable decrease in IGFBP-1 protein levels was found in the serum of Fakd (Fig. 2e). Maternal adiponectin reconstitution significantly increased fetal blood IGFBP-1 protein levels (Fig. 2f). Since fetal blood IGFBP-1 levels inversely correlate with birthweight [14, 16] and transgenic overexpression of IGFBP-1 inhibits mouse and rat fetal growth [13, 17–19], we propose that IGFBP-1 mediates adiponectin-induced inhibition of fetal growth. Consistent with this notion, we observed a significant increase in IGF-1 receptor β phosphorylation in fetal livers from Adipoq−/− dams (Fig. 2g), suggesting increased IGF-1 bioavailability and activity in fetuses of Adipoq−/− dams.

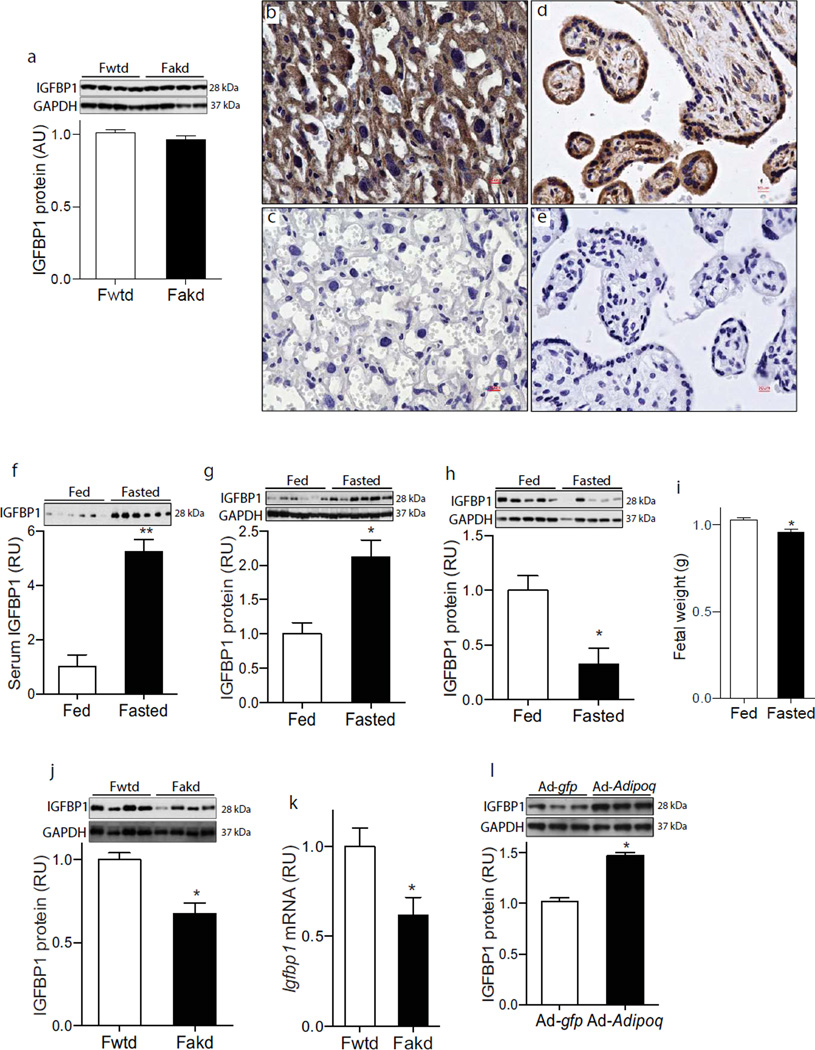

Adiponectin increases IGFBP-1 expression in mouse placentas

The liver is reported to be the major fetal mouse tissue that secretes IGFBP-1 into the circulation; however, the study did not include placentas [36]. Our results showed that maternal adiponectin gene knockout had no significant effect on fetal liver IGFBP-1 protein (Fig.3a) and mRNA levels (ESM Fig. 2a). These results indicate that the decrease in blood IGFBP-1 levels in Adipoq−/−, dams is likely caused by a mechanism independent of liver IGFBP-1 expression.

Fig. 3.

IGFBP-1 levels in trophoblast cells and the effect of maternal adiponectin on placental IGFBP-1 content. (a) IGFBP-1 protein levels were determined by western blotting of fetal liver samples (E18.5) from WT or Adipoq−/− dams obtained under normal feeding conditions (n=12). (b, c) The placental labyrinth of C57BL/6 mice at E18.5 and (d, e) the villous fraction of term human placentas were probed with (b, d; brown colour) an anti-IGFBP-1 antibody or (c, e) normal rabbit serum. Images were captured with magnification ×40. (f–j) Pregnant C57BL/6 mice were fasted overnight or fed before tissue collection at E18.5 (n=8). IGFBP-1 levels were determined by western blotting in (f) fetal blood, (g) placental or (h) fetal liver samples. (i) Overnight fasting reduced fetal weight (n=54–68). (j) IGFBP-1 levels were measured by western blotting in placental tissue samples from WT or Adipoq−/− dams (n=8). (k) Igfbp1 mRNA levels were measured by qPCR in placenta samples from WT or Adipoq−/− dams (n=8). (l) IGFBP-1 levels were measured by western blotting in placental tissue samples from Ad-gfp or Ad-Adipoq-transduced Adipoq−/− dams (n=8). RU, relative units. *p<0.05, **p<0.01

IGFBP-1 is also expressed in human decidual cells and the mouse endoderm yolk sac [37]. In the present study, immunohistochemical analysis detected IGFBP-1-positive syncytiotrophoblast cells in both mouse labyrinthine and human chorionic villi (Fig.3b–e). Furthermore, overnight maternal fasting robustly increased fetal blood IGFBP-1 protein levels and placental IGFBP-1 expression (Fig. 3f,g). Surprisingly, fetal liver IGFBP-1 protein (Fig. 3h) and mRNA levels (ESM Fig. 2b) were significantly reduced after maternal fasting. Most importantly, in contrast to the increased placental and blood IGFBP-1 protein levels, fetal body weight was remarkably reduced after maternal overnight fasting (Fig. 3i). Together, these results suggest that the placenta is an important source of fetal blood IGFBP-1. As shown in Fig. 3j,k, IGFBP-1 protein and mRNA levels were significantly decreased in placentas from Adipoq−/− dams. In contrast, maternal adiponectin reconstitution significantly increased IGFBP-1 protein levels in placentas (Fig. 3l). These results indicate that adiponectin increases IGFBP-1 gene expression in mouse placentas.

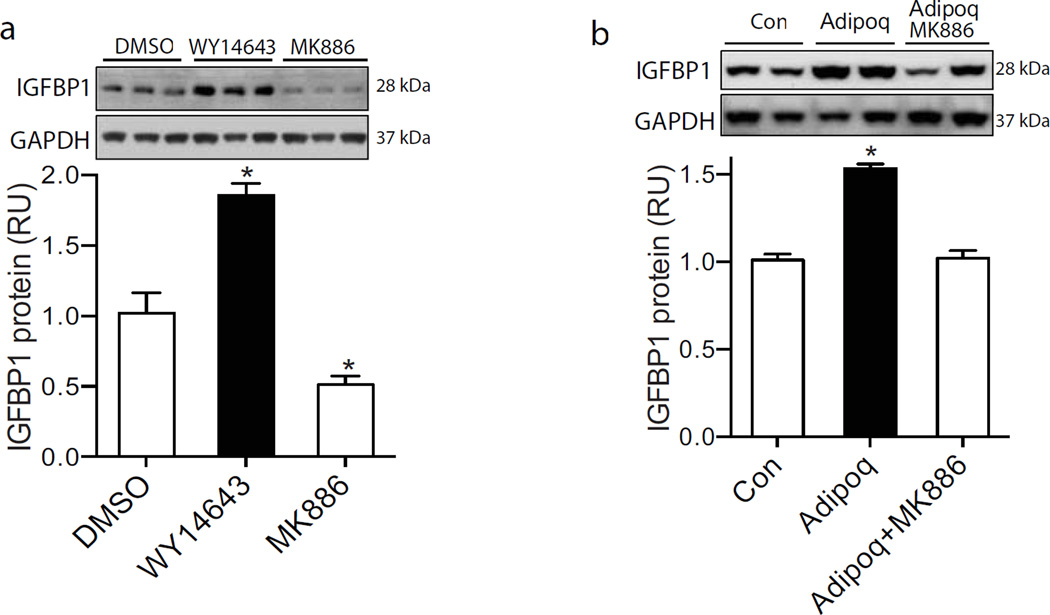

Adiponectin increases IGFBP-1 gene expression through PPARα

PPARα is a member of the PPAR transcription factor family, and is expressed in both human and rodent placentas [38, 39]. PPARα binds to the promoter region and upregulates IGFBP1 transcription in a variety of cell types [40, 41]. Adiponectin increases PPARα expression and transcriptional activity in both hepatocytes and trophoblasts [42, 43]. We therefore treated primary human trophoblast cells with the PPARα agonist WY14643 and antagonist MK886. The levels of IGFBP-1 protein were significantly increased in WY14643-treated cells and robustly decreased in MK886-treated trophoblast cells (Fig. 4a). These results indicate that PPARα upregulates IGFBP-1 gene expression in trophoblast cells.

Fig. 4.

Adiponectin enhanced the IGFBP-1 expression in trophoblast cells via PPARα. (a) IGFBP-1 levels in primary trophoblast cells treated overnight with a PPARα agonist WY14643 (5 µmol/l) or antagonist MK886 (10 µmol/l) were analysed by western blotting. (b) Adiponectin was ectopically expressed in Ad-Adipoq-transduced Fao cells. Insert wells containing transduced Fao cells were co-cultured overnight with trophoblast cells. MK886 was then added to one group of adiponectin-treated cells (Adipoq). IGFBP-1 protein levels in trophoblast cells were analysed by western blotting (n=6). RU, relative units. *p<0.05 vs control cells (Con)

Using the co-culture system and primary human trophoblast cells, we demonstrated that IGFBP-1 protein levels were robustly increased in adiponectin-treated cells (Fig. 4b), which supports our in vivo findings that maternal adiponectin increased IGFBP-1 expression in the placenta. Most importantly, this stimulatory effect was abolished by MK886 treatment (Fig. 4b). Therefore, these studies demonstrate that adiponectin increases IGFBP-1 gene expression in trophoblast cells via PPARα.

Discussion

Adiponectin is an adipocyte-derived hormone that has been suggested to mediate maternal obesity-altered fetal growth [23, 44]. Recent studies, including our work, demonstrated that adiponectin is not expressed in the placenta and cannot pass through the placental barrier [23, 33]. Furthermore, our animal study also revealed that adiponectin is not present within the fetal compartment in early life [33]. Although it is still unclear when and where adiponectin expression is initiated in the human fetus, a significant increase in fetal blood adiponectin levels occurs in the last trimester [27, 45]. In contrast, maternal adiponectin expression is significantly decreased in late pregnancy [25]. Therefore, at delivery, the neonatal blood adiponectin level is four- to sevenfold higher than the level in the mothers’ blood [45]. The opposing changes in adiponectin expression in maternal and fetal tissues during late pregnancy may explain why birthweights are inversely correlated with maternal blood adiponectin concentrations but positively associated with cord blood adiponectin concentrations [22, 23, 27, 45]. These correlations also suggest that maternal and fetal adiponectin may regulate fetal growth via different mechanisms. Therefore, we designed the present study to address whether and, if so, how maternal regulation of fetal growth occurs. By crossing Adipoq−/− and WT mice, we created adiponectin-deficient and WT dams in which all fetuses were genetically identical. This system allowed us to exclude the possible effects of fetal adiponectin. We found that body weight was significantly higher in Fakd than in Fwtd at both E14.5 and E18.5. Furthermore, maternal adiponectin reconstitution reversed the change in fetal weight to within the normal range. Therefore, these results demonstrate that maternal adiponectin suppresses fetal growth, consistent with the results of maternal adiponectin infusion [24]. The effects of fetal adiponectin on fetal growth are beyond the scope of the current study. Although our previous study revealed that fetal adiponectin increases hepatic de novo lipogenesis [33], which might provide substrates for the rapid expansion of fetal tissue at late gestation, studies designed to specifically verify the regulatory effects of fetal adiponectin on fetal growth are required.

Nutrient supply is essential for fetal growth. Previous studies showed that maternal adiponectin inhibits the expression and activity of several key amino acid transporters in trophoblast cells by suppressing insulin–mTOR signalling [24, 43]. The present study does not provide evidence that adiponectin affects placental amino acid transport. However, our results showed that adiponectin deficiency robustly increased maternal and fetal blood glucose concentrations and the fetal/placental weight ratio, supporting the idea that inhibiting placental nutrient transport might be one of the mechanisms through which maternal adiponectin suppresses fetal growth. The finding that maternal blood glucose, TG and NEFA levels in Adipoq−/− dams is significantly altered also indicates that maternal adiponectin plays a very important role in maintaining maternal metabolism homeostasis. We propose that maternal adiponectin limits fetal nutrient supply by reducing placental nutrient transport and nutrient availability at the placenta. This hypothesis is being tested in a separate study.

Fetal growth is rigorously regulated by fetal hormones, in addition to nutrient supply [7, 35]. The IGF system plays a central role in regulating fetal growth [9–12]. In addition to regulation via changes in protein levels, IGF activity is controlled by bioavailability via the high affinity binding of IGFBPs [7]. Although IGFBP-3 is the most abundant binding protein in human blood, the regulatory effects of IGFBP-3 on fetal growth are still uncertain [46–48]. In contrast to IGFBP-1, human studies have reported that cord blood IGFBP-3 concentrations do not inversely correlate, and may even positively correlate, with birthweight [46–49]. IGFBP-1 is the dominant IGF-binding protein in rodent fetal blood [13–15]. IGFBP-1 inhibits fetal growth by reducing IGF-1 bioavailability and activity [9, 12]. The results of our study indicate that maternal adiponectin increases fetal blood IGFBP-1 levels. Interestingly, although Fakd exhibited a higher growth rate, the blood total IGF-1 concentrations were similar in both Fakd and Fwtd (Fig. 2a). These results suggest that maternal adiponectin reduces IGF-1 bioavailability in the fetus. Increased IGF-1 receptor phosphorylation in Fakd livers supports this notion. Therefore, we propose that maternal adiponectin suppresses fetal growth by increasing IGFBP-1, thereby reducing IGF-1 bioavailability in fetal blood.

Another important finding of this study is the regulatory effect of maternal adiponectin on IGFBP-1 levels in trophoblast cells. To identify which fetal tissue mediates adiponectin-increased blood IGFBP-1 protein, we compared levels of IGFBP-1 in the livers of Fakd and Fwtd, because the liver is considered the main source of fetal blood IGFBP-1 [36]. However, no notable alteration of IGFBP-1 protein and mRNA levels was detected in fetal livers from an Adipoq−/− dam (Fig. 3a and ESM Fig. 2a) or after maternal adiponectin reconstitution (data not shown). These results indicate that the fetal liver is not responsible for the adiponectin-dependent increase in IGFBP-1 levels in fetal blood. These data also indicate that one or more other tissues secrete IGFBP-1 into fetal blood. We found that IGFBP-1 is expressed in trophoblast cells in both human and mouse placentas. Overnight fasting dramatically increased IGFBP-1 expression in placentas, accompanied by a fourfold increase in fetal blood IGFBP-1 protein levels and a significant reduction in fetal body weight, indicating that the placenta is another source of fetal blood IGFBP-1. We also found a significant difference in IGFBP-1 expression in placentas from Adipoq−/− and WT dams. Elevated IGFBP-1 protein was detected in placentas of maternal adiponectin-reconstituted dams and adiponectin-treated primary human trophoblast cells. In addition, a PPARα-specific antagonist abolished adiponectin-induced IGFBP-1 expression in primary trophoblast cells. Adiponectin is known to increase PPARα-dependent transcriptional activity in various cells, including trophoblasts [42]. Together, our results demonstrate that adiponectin enhances IGFBP-1 expression in trophoblast cells via PPARα. Since trophoblast cells are the main component of the interface between the maternal and fetal compartments, our finding provides a new mechanism for fetal growth regulation by maternal hormones. The placenta is an endocrine organ that secretes several hormones into the maternal blood and plays a key role in maintaining pregnancy. The discovery of IGFBP-1 in trophoblast cells extends the endocrine function of the placenta into the fetal system. However, the mechanisms by which trophoblast IGFBP-1 affects fetal growth remain to be elucidated. We also appreciate that there are significant differences in placental tissue structure between mice and humans. Therefore, further studies are required to verify the physiological function of this new component of placental endocrine system in fetal growth and its origins. The questions of how much trophoblast cell-expressed IGFBP-1 can be secreted into fetal compartments, especially in humans, whether IGFBP-1 interacts with IGF-2 locally and how this interaction regulates placenta development and nutrient transport still need to be addressed.

In conclusion, our results provide further experimental evidence that maternal adiponectin suppresses fetal growth. Our study also reveals that maternal adiponectin increases IGFBP-1 protein levels in fetal blood by increasing IGFBP-1 expression in trophoblast cells. We propose that, in addition to modulating the fetal nutrient supply, maternal adiponectin inhibits fetal growth by reducing IGF-1 bioavailability in the fetal compartment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute of Health grants (HD069634 DK095132) and an American Diabetes Association grant (no. 1–16-IBS-272), which were awarded to JSh.

Abbreviations

- Ad-gfp

Adenoviral vector encoding green fluorescent protein

- Ad-Adipoq

Adenoviral vector encoding adiponectin

- E

Embryonic day

- Fakd

Fetuses from Adipoq−/− dams

- Fwtd

Fetuses from wild-type dams

- GAPDH

Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GFP

Green fluorescent protein

- IGFBP-1

IGF-binding protein 1

- PPARα

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α

- RT

Room temperature

- TG

Triacylglycerol

- WT

Wild-type

Footnotes

Duality of interest statement

The authors declare that there is no duality of interest associated with this manuscript.

Contribution statement

JSh designed the study, and WWH and MP contributed to the study design and discussion; JSc designed and created viral vectors for in vivo transduction, LQ, J-SW, SL, ZG and MMZ contributed to data acquisition and analysis and drafting the article; JSh interpreted the data; and JSh wrote the manuscript, with a significant contribution from JSc. All authors approve the final version of this paper. JSh is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

References

- 1.Ogden CL, Fryar CD, Flegal KM. National Center for Health Statistics. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2015. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2011–2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oken E. Fetal origins of obesity. Obesity research. 2003;11:496–506. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rooney K, Ozanne SE. Maternal over-nutrition and offspring obesity predisposition: targets for preventative interventions. Int J Obes (Lond) 2011;35:883–890. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freinkel N. Banting Lecture 1980. Of pregnancy and progeny. Diabetes. 1980;29:1023–1035. doi: 10.2337/diab.29.12.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barker DJ, Thornburg KL. The obstetric origins of health for a lifetime. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2013;56:511–519. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e31829cb9ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dimasuay KG, Boeuf P, Powell TL, Jansson T. Placental responses to changes in the maternal environment determine fetal growth. Front Physiol. 2016;7:12. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2016.00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Randhawa R, Cohen P. The role of the insulin-like growth factor system in prenatal growth. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism. 2005;86:84–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2005.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Constancia M, Hemberger M, Hughes J, et al. Placental-specific IGF-II is a major modulator of placental and fetal growth. Nature. 2002;417:945–948. doi: 10.1038/nature00819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baker J, Liu JP, Robertson EJ, Efstratiadis A. Role of insulin-like growth factors in embryonic and postnatal growth. Cell. 1993;75:73–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walenkamp MJ, Losekoot M, Wit JM. Molecular IGF-1 and IGF-1 receptor defects: from genetics to clinical management. Endocrine development. 2013;24:128–137. doi: 10.1159/000342841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeChiara TM, Efstratiadis A, Robertson EJ. A growth-deficiency phenotype in heterozygous mice carrying an insulin-like growth factor II gene disrupted by targeting. Nature. 1990;345:78–80. doi: 10.1038/345078a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Powell-Braxton L, Hollingshead P, Warburton C, et al. IGF-I is required for normal embryonic growth in mice. Genes & Development. 1993;7:2609–2617. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.12b.2609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ben Lagha N, Seurin D, Le Bouc Y, et al. Insulin-like growth factor binding protein (IGFBP-1) involvement in intrauterine growth retardation: study on IGFBP-1 overexpressing transgenic mice. Endocrinology. 2006;147:4730–4737. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chard T. Insulin-like growth factors and their binding proteins in normal and abnormal human fetal growth. Growth regulation. 1994;4:91–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gupta MB. The role and regulation of IGFBP-1 phosphorylation in fetal growth restriction. J Cell Commun Signal. 2015;9:111–123. doi: 10.1007/s12079-015-0266-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holly JM, Perks CM. Insulin-like growth factor physiology: what we have learned from human studies. Endocrinology and metabolism clinics of North America. 2012;41:249–263. v. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crossey PA, Pillai CC, Miell JP. Altered placental development and intrauterine growth restriction in IGF binding protein-1 transgenic mice. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:411–418. doi: 10.1172/JCI10077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gay E, Seurin D, Babajko S, Doublier S, Cazillis M, Binoux M. Liver-specific expression of human insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1 in transgenic mice: repercussions on reproduction, ante-and perinatal mortality and postnatal growth. Endocrinology. 1997;138:2937–2947. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.7.5282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rajkumar K, Barron D, Lewitt MS, Murphy LJ. Growth retardation and hyperglycemia in insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1 transgenic mice. Endocrinology. 1995;136:4029–4034. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.9.7544274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tosh DN, Fu Q, Callaway CW, et al. Epigenetics of programmed obesity: alteration in IUGR rat hepatic IGF1 mRNA expression and histone structure in rapid vs. delayed postnatal catch-up growth. American journal of physiology Gastrointestinal and liver physiology. 2010;299:G1023–G1029. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00052.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee B, Shao J. Adiponectin and energy homeostasis. Reviews in endocrine & metabolic disorders. 2014;15:149–156. doi: 10.1007/s11154-013-9283-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jansson N, Nilsfelt A, Gellerstedt M, et al. Maternal hormones linking maternal body mass index and dietary intake to birth weight. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2008;87:1743–1749. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.6.1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aye IL, Powell TL, Jansson T. Review: Adiponectin--the missing link between maternal adiposity, placental transport and fetal growth? Placenta. 2013;34(Suppl):S40–S45. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2012.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosario FJ, Schumacher MA, Jiang J, Kanai Y, Powell TL, Jansson T. Chronic maternal infusion of full-length adiponectin in pregnant mice down-regulates placental amino acid transporter activity and expression and decreases fetal growth. J Physiol. 2012;590:1495–1509. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.226399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Catalano PM, Hoegh M, Minium J, et al. Adiponectin in human pregnancy: implications for regulation of glucose and lipid metabolism. Diabetologia. 2006;49:1677–1685. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0264-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Soheilykhah S, Mohammadi M, Mojibian M, et al. Maternal serum adiponectin concentration in gestational diabetes. Gynecological endocrinology: the official journal of the International Society of Gynecological Endocrinology. 2009;25:593–596. doi: 10.1080/09513590902972109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chan TF, Yuan SS, Chen HS, et al. Correlations between umbilical and maternal serum adiponectin levels and neonatal birthweights. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2004;83:165–169. doi: 10.1111/j.0001-6349.2004.0298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nawrocki AR, Rajala MW, Tomas E, et al. Mice lacking adiponectin show decreased hepatic insulin sensitivity and reduced responsiveness to peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma agonists. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:2654–2660. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505311200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qiao L, MacLean PS, Schaack J, et al. C/EBPalpha regulates human adiponectin gene transcription through an intronic enhancer. Diabetes. 2005;54:1744–1754. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.6.1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li Y, Moretto-Zita M, Soncin F, et al. BMP4-directed trophoblast differentiation of human embryonic stem cells is mediated through a ΔNp63+ cytotrophoblast stem cell state. Development. 2013;140:3965–3976. doi: 10.1242/dev.092155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qiao L, Kinney B, Schaack J, Shao J. Adiponectin inhibits lipolysis in mouse adipocytes. Diabetes. 2011;60:1519–1527. doi: 10.2337/db10-1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qiao L, Zou C, van der Westhuyzen DR, Shao J. Adiponectin reduces plasma triglyceride by increasing VLDL triglyceride catabolism. Diabetes. 2008;57:1824–1833. doi: 10.2337/db07-0435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qiao L, Yoo HS, Madon A, Kinney B, Hay WW, Shao J. Adiponectin enhances mouse fetal fat deposition. Diabetes. 2012;61:3199–3207. doi: 10.2337/db12-0055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qiao L, Yoo HS, Bosco C, et al. Adiponectin reduces thermogenesis by inhibiting brown adipose tissue activation in mice. Diabetologia. 2014;57:1027–1036. doi: 10.1007/s00125-014-3180-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Milner RD, Hill DJ. Fetal growth control: the role of insulin and related peptides. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1984;21:415–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1984.tb03229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Kleffens M, Groffen CA, Dits NF, et al. Generation of antisera to mouse insulin-like growth factor binding proteins (IGFBP)-1 to-6: comparison of IGFBP protein and messenger ribonucleic acid localization in the mouse embryo. Endocrinology. 1999;140:5944–5952. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.12.7168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carter AM, Nygard K, Mazzuca DM, Han VK. The expression of insulin-like growth factor and insulin-like growth factor binding protein mRNAs in mouse placenta. Placenta. 2006;27:278–290. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang Q, Fujii H, Knipp GT. Expression of PPAR and RXR isoforms in the developing rat and human term placentas. Placenta. 2002;23:661–671. doi: 10.1053/plac.2002.0855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wieser F, Waite L, Depoix C, Taylor RN. PPAR action in human placental development and pregnancy and its complications. PPAR research. 2008;2008:527048. doi: 10.1155/2008/527048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Degenhardt T, Matilainen M, Herzig KH, Dunlop TW, Carlberg C. The insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 1 gene is a primary target of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:39607–39619. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605623200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van der Meer DL, Degenhardt T, Vaisanen S, et al. Profiling of promoter occupancy by PPARalpha in human hepatoma cells via ChIP-chip analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:2839–2850. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aye IL, Gao X, Weintraub ST, Jansson T, Powell TL. Adiponectin inhibits insulin function in primary trophoblasts by PPARalpha-mediated ceramide synthesis. Molecular endocrinology. 2014;28:512–524. doi: 10.1210/me.2013-1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jones HN, Jansson T, Powell TL. Full-length adiponectin attenuates insulin signaling and inhibits insulin-stimulated amino acid transport in human primary trophoblast cells. Diabetes. 2010;59:1161–1170. doi: 10.2337/db09-0824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aye IL, Rosario FJ, Powell TL, Jansson T. Adiponectin supplementation in pregnant mice prevents the adverse effects of maternal obesity on placental function and fetal growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:12858–12863. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1515484112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sivan E, Mazaki-Tovi S, Pariente C, et al. Adiponectin in human cord blood: relation to fetal birth weight and gender. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:5656–5660. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Giudice LC, de Zegher F, Gargosky SE, et al. Insulin-like growth factors and their binding proteins in the term and preterm human fetus and neonate with normal and extremes of intrauterine growth. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80:1548–1555. doi: 10.1210/jcem.80.5.7538146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lappas M. Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 1 and 7 concentrations are lower in obese pregnant women, women with gestational diabetes and their fetuses. Journal of perinatology : official journal of the California Perinatal Association. 2015;35:32–38. doi: 10.1038/jp.2014.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Klauwer D, Blum WF, Hanitsch S, Rascher W, Lee PD, Kiess W. IGF-I, IGF-II, free IGF-I and IGFBP-1,-2 and-3 levels in venous cord blood: relationship to birthweight, length and gestational age in healthy newborns. Acta paediatrica (Oslo, Norway : 1992) 1997;86:826–833. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1997.tb08605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hung TY, Lin CC, Hwang YS, Lin SJ, Chou YY, Tsai WH. Relationship between umbilical cord blood insulin-like growth factors and anthropometry in term newborns. Acta paediatrica Taiwanica = Taiwan er ke yi xue hui za zhi. 2008;49:19–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.