Summary

Background

There is a dearth of effective community-based interventions to increase HIV testing and uptake of antiretroviral therapy (ART) among pregnant women in hard–to-reach resource-limited settings. We assessed whether a faith-based intervention, the Healthy Beginning Initiative (HBI), would increase uptake of HIV testing and ART among pregnant women as compared to health facility referral.

Methods

This trial was conducted in southeast Nigeria, between January 20, 2013, and August 31, 2014. Eligible churches had at least 20 annual infant baptisms. Forty churches (clusters), stratified by number of infant baptisms (<80 vs. >80) were randomized 1:1 to intervention (IG) or control (CG). Three thousand and two (3002) self-identified pregnant women aged 18 and older participated. Intervention included heath education and onsite laboratory testing implemented during baby shower in IG churches, while participants in CG churches were referred to health facilities. Primary outcome (confirmed HIV testing) and secondary outcome (receipt of ART during pregnancy) were assessed at the individual level.

Findings

Antenatal care attendance was similar in both groups (IG=79.4% [1309/1647] vs. CG=79.7% [1080/1355], P=0.8). The intervention was associated with higher HIV testing (CG=54.6% [740/1355] vs. IG =91.9% [1514/1647]; [AOR= 11.2; 95% CI: 8.77-14.25, P-value=<0.001]. Women in the IG were significantly more likely to be linked to care prior to delivery (P<0.01) and more likely to have received ART during pregnancy (P=0.042) compared to those in the CG.

Interpretation

Culturally-adapted, community-based programs such as HBI can be effective in increasing HIV screening and ART among pregnant women in resource-limited settings.

Funding

National Institute of Health and President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief

INTRODUCTION

Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) has the highest burden of the human immunodeficiency virus and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) in the world. Although SSA countries account for 13% of the world population, it is home to 71% of persons living with HIV globally. Due to a plethora of biological, cultural, and economic factors, women are disproportionately affected by HIV, and represent over half of all adults living with HIV in SSA.1

Although mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) of HIV has almost been eliminated in many high-income countries, it remains an important source of new HIV infection in SSA countries. According to the 2014 report of the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), SSA accounted for 87% of the 1.5 million pregnant women living with HIV and 91% of children living with HIV worldwide. In spite of improved effort and the availability of simple, relatively inexpensive and highly effective antiretroviral (ARV) regimens for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV (PMTCT), 32% of pregnant women did not receive antiretroviral therapy for PMTCT resulting in an estimated 210,000 new child infections.1

Nigeria is one of 21 priority countries in SSA that together with India, account for 90% of pregnant women infected with HIV. In 2013, Nigeria had a HIV testing rate of less than 20% among pregnant women and accounted for 26% of all new child infections in the 21 priority countries.1-3 Identification of HIV-infected pregnant women through routine HIV screening remains a critical step necessary to initiate interventions designed for PMTCT. Currently, most pregnant women access clinics through the healthcare system to undertake HIV screening and receive available PMTCT interventions. Such a clinic-based approach is challenging when only 35% of deliveries occur in hospitals and only 2.9% of healthcare facilities have effective PMTCT programs.4 Thus, finding new approaches to translate evidence-based interventions in PMTCT to sustainable community-based programs is imperative to realize the WHO/PEPFAR goal of eliminating new pediatric HIV infections by 2015.2

Ranked number one among 53 other nations in church attendance, Nigeria has extensive network of faith-based institutions, and faith plays a significant role in the social life of Nigerians. Religious leaders in Nigeria are knowledgeable about HIV and can harness their position for HIV prevention.5-7 Building on this background, we developed the Healthy Beginning Initiative (HBI), a culturally adapted, family-centered approach that relies on the widely distributed religious infrastructure and church-based community networks to promote individual testing, tracking and retention of participants.

A cluster randomized trial of 40 churches was conducted in southeast Nigeria. We considered randomizing each individual patient, but the likelihood of contamination posed a threat to internal validity; thus, individual pregnant women were nested within the church. The communities where the churches were located had similar ethnic group composition, culture, language and church attendance. We also considered a cross-over design, but the possibility of withdrawing an intervention if it was effective would make this design problematic. The primary outcome measure was confirmed HIV testing and the secondary outcome was antiretroviral therapy (ART) for pregnant women identified to be HIV-infected. We hypothesized that pregnant women randomized to the intervention group (IG) will have a higher rate of HIV testing and receipt of ART compared to those randomized to control group (CG).

METHODS

Trial Design

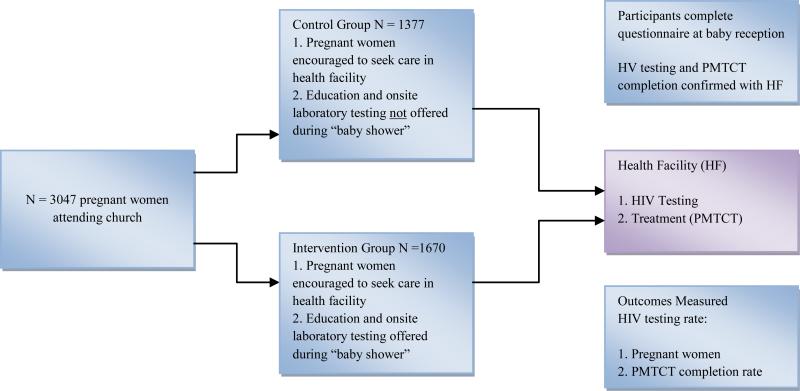

This two-arm cluster randomized trial design evaluated the effect of a congregation-based HBI that provided free, integrated on-site laboratory tests during a church-organized baby shower as the intervention group [IG] versus a clinic-based referral approach as the control group [CG] on the rate of HIV testing and receipt of ART among pregnant women. Randomization occurred at the level of the clusters (churches) while outcome data was collected at the individual (participant) level. Forty churches in Enugu State, southeast Nigeria, were enrolled and randomly assigned to either the IG (N = 20 churches) or the CG (N = 20 churches). Participants in churches randomized to IG received health education and were offered an HIV test as part of an integrated (hemoglobin, malaria, syphilis, HIV, sickle cell genotype, hepatitis B) on-site laboratory test during church-organized baby shower program. During the baby shower, participants in churches randomized to the CG were referred to the closest healthcare facility for HIV testing and prenatal care. Participants completed an investigator-administered questionnaire to collect information on HIV testing. HIV testing and receipt of ART was confirmed with the healthcare facility for participants in CG churches. On-site HIV testing data and health facility data were used to confirm HIV testing and receipt of ART for participants in IG churches (Figure 1). Participants in both IG and CG received three study visits; one at baseline (recruitment), one during the baby shower, and one at six to eight weeks after delivery for the baby reception.

Figure 1.

Overview of HBI

Study setting and participants

Enugu State in southeast Nigeria was selected for a number of reasons: first, its population is culturally and ethnically related and predominately Christian, with church attendance approaching 90%5,6; second, the overall state HIV sero-prevalence of 5.1% is close to the national average of 4.1%; third, the participating churches were widely distributed and represented variations in the prevalence rate of HIV across the state of 4% to 8% (6% average). We focused on a congregation-based intervention as such interventions have been used effectively in health promotion in communities where faith plays a significant role, such as Nigeria with 87% reporting religious service attendance at least once a week.5, 6, 8-12 Faith-based organizations (FBOs) are already involved in general HIV education and awareness in Nigeria and their role increased with implementation of the 2010-2015 National Strategic Framework.7,13,14

We evaluated 200 churches and collected data on infant baptism for the three years preceding the study (2010, 2011 and 2012). Infant baptism was used as an indirect measure of the potential size of pregnant women in the churches. In most cases, we selected one church in each community to maintain a distance between participating sites. Most of the communities were at least 5km (3.1 miles) apart with some as far as 20km (12.5 miles) apart. Self-identified pregnant women 18 years and older that attended any of the study sites were eligible to participate. Women were encouraged to participate with their male partners, but could still participate if their male partner chose not to participate. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Nevada, Reno, and the Nigerian National Health Research Ethics Committee.

Staff recruitment and training

For this study, the funding agencies mandated that we have a local PEPFAR supported partner working in the area of the proposed research. Our local partner - Prevention, education, treatment, Training and Research-Global Solutions (PeTR-GS), working with Sunrise Foundation, a local non-governmental organization (NGO), conducted training workshops for all study staff and church-based volunteer health advisors. They received training on the study protocol, including how to obtain informed consent, data collection forms, and confidentiality. Additionally, study staff received information on HIV counseling, delivery of HIV test results and post-test counseling. Although priests were not actively involved in the main intervention, they received basic information on HIV transmission, MTCT, PMTCT, and HIV counseling methodology.

Recruitment of participants

Prayer Sessions

Recruitment began following randomization of the churches. Each Sunday, the priest asked pregnant women and their male partners in the congregation to step to the altar for prayers. He prayed for a healthy pregnancy, successful delivery, and encouraged pregnant women to seek care at a health facility during their pregnancy. He introduced HBI and the study team as a program supporting pregnant women in the congregation during pregnancy, and described the program's objectives. Pregnant women and their male partners were encouraged to participate.

Description of the intervention

Baby Shower

Held one Sunday each month for pregnant women and their families. Participants were provided with information on the six conditions included in the integrated tests. Participants also received a “Mama Pack” provided by the church and distributed by their male partner or by the clergy. The Mama Pack contained basic essentials of benefit to a pregnant woman during delivery including sanitary pads, clean razor blade, alcohol and gloves. It was given to all participating pregnant women bearing in mind that less than 50% of them will deliver in a health facility. Free integrated laboratory tests were offered to pregnant women during the baby shower, including tests for hemoglobin, malaria, sickle cell genotype, HIV, hepatitis B, and syphilis. This integrated testing was designed to reduce stigma associated with HIV-only testing. Women identified as HIV+ were linked to PeTR-GS comprehensive HIV program. One advantage of this approach was avoiding duplicate testing by providing copies to participants to make available to staff at health facilities where they attended prenatal care.

Baby Reception

Held one Sunday every two to three months to celebrate births with baby gifts and refreshments. Participants completed a post-delivery questionnaire to ascertain and document HIV testing during pregnancy, and pregnancy outcome. It also provided an opportunity for follow-up with women needing ongoing care post-delivery.

Description of the control condition/usual care

Prayer sessions, Baby Showers and Baby Receptions were conducted in churches randomized to CG similar to churches in IG with the exception that the intervention(Health education on health conditions and on-site integrated laboratory testing) was not provided during baby showers. Participants in CG churches were encouraged to attend prenatal care at the health facilities where they had access to HIV testing as is usual practice. The health facilities were partners in the research through collaboration with our local PEPFAR supported partner PETR-GS. Participants were asked to bring copies of their prenatal tests to research staff and were made aware that their laboratory tests would be confirmed with health facilities.

Aims and outcome measures

The primary aim was to determine difference in HIV testing between the two groups and define the predictors for HIV testing. The primary outcome measure was confirmed HIV testing during pregnancy. HIV testing among women in churches randomized to CG were confirmed at the health facility where pregnant women reported prenatal care. Although we are aware of the potential limitations with confirming HIV test results at health facilities, we were also conscious of the unreliability of self-reported HIV testing. Given confidence in our ability to confirm most HIV tests performed at surrounding health facilities, we chose to use confirmed HIV test for both groups as primary outcome measure.

The secondary aims were to evaluate the effect of HBI on the rate of PMTCT completion among HIV-infected pregnant women measured by linkage to care and receipt of ART for HIV-infected pregnant women and on the rate of HIV testing among male partners. This manuscript reports study findings on the impact of HBI on HIV testing among pregnant women and PMTCT completion among HIV-infected pregnant women. Findings on the impact of HBI on male partner testing will be reported separately.

Sample Size

There were two important sample size estimates. First is N, the number of pregnant women and K, the number of churches, with the pregnant women nested within the K churches. Power calculations were performed using the module Inequality Tests for Two Proportions in a Cluster-Randomized Design in PASS 11, which implements methods of Donner and Klar.15 That module approximates power for simple two-sample binomial tests for data collected in clusters with non-zero intra-cluster correlation (ICC). With ICC at 0.10, we would need a sample size to have enough sample to recruit at least 140 HIV infected women. After considering factors like HIV prevalence rate among women and drop rate, the sample size designed as approximately 2,700 total pregnant women (1350 per group). A detailed sample size calculation and analysis plan has been described previously.16

Randomization

Recruitment occurred at the level of the churches and participants (in that order), while randomization occurred only at the church level. A total of 40 churches were selected and ranked according to size based on number of infant baptisms (indirect number of pregnant women). Randomization of churches occurred 1:1 in 4 cohorts of 10 churches following the ranking order (largest to smallest). The sequence of randomization was generated by the study biostatistician, Dr. Wei Yang, MD, PhD, and kept in a sealed opaque envelope away from the study sites in accordance with CONSORT guidelines.17 Once the sites were recruited and baseline information on churches collected (e.g., type, size of congregation), the sites were informed of their randomization group and assigned a code. Participants followed the randomization of the church they attend. Because of the nature of the intervention, it was impossible to blind the participants, community health nurses, volunteer health advisors, and study coordinators to the group assignment.

Statistical Methods

Our hypothesis test for differences in two binomial proportions at follow-up and data was analyzed with following statistical tests. The chi-square statistic was used to assess differences in HIV-Test proportions. The Student's t-test was used to assess differences in continuous data. Multilevel analysis generalized linear mixed models (GLIMMIX) were implemented with that procedure using a logit link function and the binomial distribution. These are multilevel models allowing incorporation of covariates and confounders for the individual (such as age, education level, previous HIV testing) and cluster-level (church) covariates and confounders such as size of church and congregation type (Anglican or Catholic). Adjusted Odds Ratios (ORs) between HIV-tested and HIV-non-tested were obtained controlling above mentioned covariates and potential confounding factors All statistical significance tests were set as P-value < 0.05 and tests were 2-sided. Statistical Analysis Systems (SAS-9.4) was used for the analyses.

Role of the Funding Source

The funding agencies played no role in the study conception, design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of the report. The corresponding author, Dr. Ezeanolue, had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. All authors vouch for the completeness and accuracy of data and data analyses and for the fidelity of the study to the protocol.

RESULTS

Recruitment

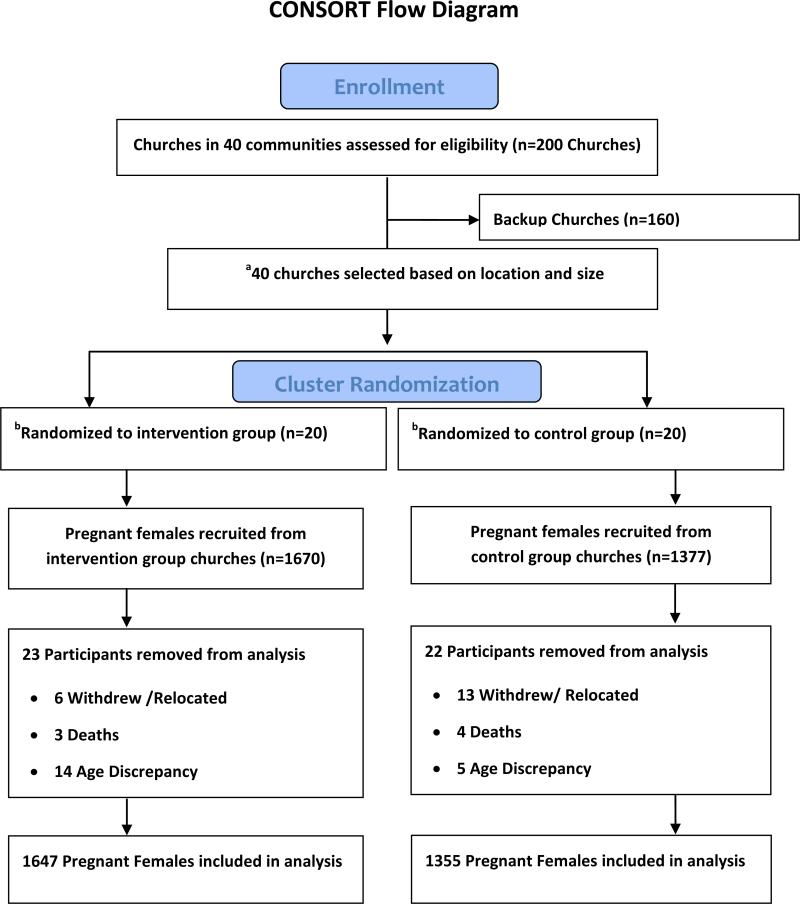

We began enrollment on January 20, 2013 and completed enrollment by September 29, 2013. Follow-up of enrolled participants was completed on August31, 2014. Of the 3047 pregnant women enrolled across 40 churches (20 in the IG and 20 in the CG), 45 participants were excluded from final analysis due to the following reasons: withdrew from the study (5), relocated (14), died (7) or conflicting age in the pre- and post-delivery questionnaire that indicate they are younger than study required age of 18 year old (19). Thus, a total 3002 enrolled participants were included in the final analysis (Figure 2). Results showed that observed ICC was 0.14 which indicated that clustering effects existed and parishioners within the same church could be expected to exhibit correlations. Therefore multilevel analysis using generalized linear mixed models (GLIMMIX) were implemented with that procedure using a logit link function and the binomial distribution.

Figure 2. Healthy Beginning Initiative Participant flow chart.

a. Selected church has to be centrally located in the community and had at least 20 infant baptisms performed each year for the past 3 years.

b. Additional 44 smaller churches close to coordinating churches were assigned to intervention group and an additional 23 smaller backup churches close to coordinating churches were assigned to control group. These smaller churches follow the randomization group of the main coordinating church using a spoke and wheel approach.

Baseline characteristics

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of study participants. In general, participants from both control and intervention groups have similar demographics, including family size, marital status, number of previous pregnancies, antenatal care attendance during pregnancy and distance to the nearest health facility. Some demographic factors show statistically significance differences. For example, the control group were 0.4 years older, are more likely to have tertiary level education (20.55% [512/1348] vs. 14.39% [235/1633]), are more likely to have full time employment (37.68% [506/1343] vs. 35.68% [573/1606]), more reside in urban areas (34.6% [466/1346] vs. 21.8% [356/1632]) and more likely to have previously tested for HIV (73.9% [1001/1355] vs. 60.8% 1001/1647]).

Table 1.

Subject Baseline Characteristics

| Characteristic | Total | Control Group | % | Intervention Group | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Subjects | 3002 | 1355 | 1647 | |||

| Age | Mean (STD) | 29.7 (5.8) | 29.3 (5.9) | |||

| Age Group | 16-24.9 | 665 | 288 | 21.27 | 377 | 23.24 |

| 25-34.9 | 1793 | 831 | 61.37 | 962 | 59.31 | |

| 35+ | 518 | 235 | 17.36 | 283 | 17.45 | |

| Marital Status | Divorced | 2 | 2 | 0.15 | 0 | 0 |

| Married | 2809 | 1278 | 94.32 | 1531 | 92.96 | |

| Separated | 15 | 7 | 0.52 | 8 | 0.49 | |

| Single | 176 | 68 | 5.02 | 108 | 6.56 | |

| Education Level | None/Primary | 778 | 330 | 24.48 | 448 | 27.43 |

| Secondary | 1691 | 741 | 54.97 | 950 | 58.18 | |

| Tertiary | 512 | 277 | 20.55 | 235 | 14.39 | |

| Employment | Full Time | 1079 | 506 | 37.68 | 573 | 35.68 |

| Part Time | 671 | 270 | 20.1 | 401 | 24.97 | |

| Unemployed | 1199 | 567 | 42.22 | 632 | 39.35 | |

| Family Size | <=2 | 484 | 227 | 16.93 | 257 | 15.94 |

| 3-6 | 2070 | 935 | 69.72 | 1135 | 70.41 | |

| >=7 | 399 | 179 | 13.35 | 220 | 13.65 | |

| Distance to Health Facility | 0-5km | 1015 | 486 | 36.32 | 529 | 32.55 |

| 5-10 km | 1149 | 520 | 38.86 | 629 | 38.71 | |

| 10-15 km | 506 | 211 | 15.77 | 295 | 18.15 | |

| 15+ km | 293 | 121 | 9.04 | 172 | 10.58 | |

| Residency Area | Rural | 2156 | 880 | 65.38 | 1276 | 78.19 |

| Urban | 822 | 466 | 34.62 | 356 | 21.81 | |

| Age at Frist Pregnancy | < 24.9 | 1849 | 805 | 61.64 | 1044 | 67.35 |

| 25-34.9 | 963 | 474 | 36.29 | 489 | 31.55 | |

| 35+ | 44 | 27 | 2.07 | 17 | 1.1 | |

| Number of Previous Pregnancies | 0 | 401 | 168 | 12.89 | 233 | 14.97 |

| 1-3 | 1633 | 758 | 58.17 | 875 | 56.23 | |

| 4+ | 825 | 377 | 28.93 | 448 | 28.79 | |

| Did Mother Receive Antenatal Care? | No | 613 | 275 | 20.3 | 338 | 20.52 |

| Yes | 2389 | 1080 | 79.7 | 1309 | 79.48 | |

| Self-Reported Previous HIV Testing | No | 1000 | 354 | 26.13 | 646 | 39.22 |

| Yes | 2002 | 1001 | 73.87 | 1001 | 60.78 | |

HIV testing among pregnant women (primary outcome)

Table 2 shows rates of HIV testing between control group and intervention group, and between other related factors. HIV testing rate among pregnant women in IG was 91.92% [1514/1647] compared to 54.61% [740/1355] among women in CG. Factors associated with having significantly higher HIV testing rate were full-time or part-time employment compared to unemployment (76.65% [827/1079] or 77.79% [522/671] vs. 72.56% 870/1199]), younger age at first pregnancy (16-24.9, 25-34.9 vs. 35+: 74.09% [1370/1849], 78.09% [752/963] vs. 63.64% [28/44]), and lower number of previous pregnancy (0, 81.3% [326/401] vs. 1-3, 74.04% [1229/1660] vs. 4+, 76.07% [607/798]).

Table 2.

Predictors of HIV testing among pregnant women

| Total Subjects (N) | Tested (N) | Rate (%) | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confirmed HIV Test | Control | 1355 | 740 | 54.61 | <0.001* |

| Intervention | 1647 | 1514 | 91.92 | ||

| Age Group | <24.9 | 665 | 492 | 73.98 | 0.753 |

| 25-34.9 | 1793 | 1350 | 75.29 | ||

| 35+ | 518 | 392 | 75.68 | ||

| Marital Status | Divorced | 2 | 2 | 100 | 0.615 |

| Married | 2809 | 2114 | 75.26 | ||

| Separated | 15 | 10 | 66.67 | ||

| Single | 176 | 128 | 72.73 | ||

| Education Level | None/Primary | 778 | 576 | 74.04 | 0.448 |

| Secondary | 1691 | 1272 | 75.22 | ||

| Tertiary | 512 | 395 | 77.15 | ||

| Employment | Full Time | 1079 | 827 | 76.65 | 0.017* |

| Part Time | 671 | 522 | 77.79 | ||

| Unemployed | 1199 | 870 | 72.56 | ||

| Family Size | <=2 | 484 | 359 | 74.17 | 0.736 |

| 3-6 P | 2070 | 1560 | 75.36 | ||

| >=7 | 399 | 305 | 76.44 | ||

| Distance to Health Facility | 0-5km | 1015 | 758 | 74.68 | 0.277 |

| 5-10 km | 1149 | 854 | 74.33 | ||

| 10-15 km | 506 | 394 | 77.87 | ||

| 15+ km | 293 | 229 | 78.16 | ||

| Residency Area | Rural | 2156 | 1635 | 75.83 | 0.260 |

| Urban | 822 | 607 | 73.84 | ||

| Age at First Pregnancy | <24.9 | 1849 | 1370 | 74.09 | 0.013* |

| 25-34.9 | 963 | 752 | 78.09 | ||

| 35+ | 44 | 28 | 63.64 | ||

| Number of Previous Pregnancies | 0 | 401 | 326 | 81.3 | 0.009* |

| 1-3 | 1660 | 1229 | 74.04 | ||

| 4+ | 798 | 607 | 76.07 | ||

| Ever Tested for HIV (self-Reported) | No | 1000 | 729 | 72.90 | 0.051 |

| Yes | 2002 | 1525 | 76.17 | ||

Results were considered statistically significant when P<0.05.

Adjusted Odds Ratio for not getting HIV test among pregnant women

Table 3 shows the odds ratios after controlling all demographic factors and other potential predictors for having no HIV testing among pregnant women. The odds for pregnant women not had HIV tested in control group were 11.2 times higher than that in intervention group (aOR: 11.18, 95% confidence interval: 8.78-14.25 and P< 0.0001) after controlling for age, educational level, employment, area of residence, age at first pregnancy, number of previous pregnancies and a history of previous HIV testing. Other significant or marginally significant factors for not getting an HIV test include full-time employment, lower number of previous births and previous HIV testing.

Table 3.

Adjusted Odds Ratio for No HIV Testing among Pregnant Women

| Variable | aOR | 95% C.I. | 95% C.I | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control vs. Intervention | 11.180 | 8.772 | 14.249 | <0.001* |

| Age group 35+ vs <24.9yr | 1.129 | 0.758 | 1.681 | 0.552 |

| Age group 25-34.9 vs <24.9 yr | 1.008 | 0.760 | 1.336 | 0.958 |

| Education Level Secondary vs. None | 0.982 | 0.764 | 1.263 | 0.888 |

| Education Level Tertiary vs. None | 0.870 | 0.608 | 1.245 | 0.445 |

| Working Part-Time vs. Full-Time | 0.964 | 0.729 | 1.274 | 0.795 |

| Working Unemployed vs. Full-Time | 1.264 | 1.006 | 1.588 | 0.045* |

| Distance to Healthcare Facility 5-10KM vs. 0-5KM | 1.159 | 0.762 | 1.401 | 0.212 |

| Distance to Healthcare Facility 10-15KM vs. 0-5KM | 1.159 | 0.919 | 1.462 | 0.835 |

| Distance to Healthcare Facility 15+KM vs. 0-5KM | 1.033 | 0.762 | 1.401 | 0.895 |

| Household Size 4-6 vs. <=3 | 0.801 | 0.581 | 1.105 | 0.177 |

| Household Size >=7 vs. <=3 | 0.731 | 0.473 | 1.129 | 0.158 |

| Living Area Urban vs. Rural | 0.833 | 0.655 | 1.060 | 0.138 |

| Age of first pregnancy group 35+ vs <24.9 yr | 1.040 | 0.435 | 2.487 | 0.929 |

| Age of first pregnancy group 25-34.9. vs < 24.9 yr | 0.748 | 0.579 | 0.965 | 0.025* |

| Number of Previous Births 1-3 vs. 0 | 1.657 | 1.157 | 2.373 | 0.006* |

| Number of Previous Births 4+ vs. 0 | 1.443 | 0.933 | 2.232 | 0.099 |

| Self-Reported Previous HIV Testing Yes vs No | 1.711 | 1.358 | 2.156 | <0.001* |

Results were considered statistically significant when P<0.05.

** Adjusted Odds Ratios (aOR) were based on multilevel analysis generalized linear mixed models (GLIMMIX) model with covariates of demographics, previous birth and previous HIV testing.

Result of HIV testing, linkage to care and ART

Seventy-three women in this study had a positive HIV test. We did not reach the preset number (140 HIV+ pregnant women) for this aim. The prevalence of HIV among this population was 2.43% (73/3002) without a significant difference between the control and intervention groups. Eighty-two percent (34/41) of the IG and 44% (14/32) of the CG were linked to care prior to delivery. Women in the IG were significantly (P<0.01) more likely to be linked to care prior to delivery and odds ratio calculations showed that linkage to care was 6.2 times higher in the IG than in the CG. Significantly (P=0.042) more women in the IG (64.9% [24/41]) accessed care and received ART during pregnancy compared to the CG (40% [12/32]). Women in the IG were 2.8 times more likely to have accessed care during pregnancy. Eighty-four percent [61/73] of all women are currently accessing care with no significant difference between groups (Table 4).

Table 4.

Outcomes of HIV Testing and Linkage to Care

| Characteristic | Total | % | Control Group | % | Intervention Group | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV Positive | 73 | 2.43 | 32 | 2.36 | 41 | 2.49 |

| Linked to care | 48 | 47.90 | 14 | 43.80 | 34 | 82.90 |

| ART during pregnancy | 36 | 53.70 | 12 | 40.00 | 24 | 64.90 |

| Currently accessing care | 61 | 83.60 | 28 | 87.50 | 33 | 80.50 |

* Results were considered statistically significant when P<0.05.

DISCUSSION

Our study findings show that a culturally adapted, congregation-based approach delivered by trained volunteer health advisors can be used effectively to increase HIV testing among pregnant women. HIV counseling and testing is an important entry point for most forms of HIV prevention and control including PMTCT. While barriers to HIV testing have been identified at the patient, provider and health systems levels, barriers at the health systems level have been identified to have the most adverse impact to HIV testing among pregnant women.18,19

Data from Nigeria indicate that in 2013, only 17.1% of women aged 15-49% received an HIV test in the past 12 months and knew their result.3 Lack of knowledge, low perception of personal risk, access, cost, stigma and the fact that most women do not access prenatal care early in pregnancy are commonly identified barriers.20-22 HBI was designed to overcome these barriers. Our finding is consistent with other studies which show that well-developed community-based approaches that decentralize testing beyond health facilities and consistently made HIV tests available in environments that reduce these barriers,23-25 have led to increased HIV testing.26-30

We believe that several factors contributed to the magnitude of the effect seen in our study with regard to HIV testing. For example: (a) Prayer sessions were useful for early identification of pregnant women. This provides multiple opportunities to offer HIV counseling and testing; (b) the integrated and onsite approach to laboratory testing provided during church–organized baby showers was reported by participants as a significant factor in the reduction of stigma associated with HIV-only testing approach; (c) involvement of male partners (who presented the mama packs to their spouses) removed the preconception of “a women only affair” and presented the baby showers as a family-oriented program. Male involvement has been shown to be a critical factor in pregnant women's acceptance of HIV testing.31

The strength of our study includes the fact that it took into consideration several factors that may affect HIV testing in Nigeria. Considering the role of faith among Nigerians, we collaborated with faith-based organizations that have well-established social networks and are already involved in current efforts to address HIV/AIDS in the study communities.32 Most communities in Nigeria have at least one worship center even when there are no accessible health facilities. Recent studies show that church-based clinics and hospitals play significant role in prenatal care and deliveries for pregnant women, and that priests rank highly among persons to whom a pregnant woman is most likely to disclose her HIV status.7 We identified and used evidence-based elements of a successful program in communities where faith plays a prominent role.33,34

Churches were used as venues to identify pregnant women, implement the intervention and for post-delivery follow up, and thus, served as the study venue. This is similar to the use of CVS, Walgreens, etc. for influenza immunization in the US.35 These neighborhood stores are used because they are easily accessible, widely distributed and as highly patronized as worship centers in most resource-limited settings. HBI is currently being adapted for implementation in Mosques in Northern Nigeria and Hindu Temples in India. We expect to see similar result as these venues serve similar function as the churches or neighborhood stores in the US. Although community-based testing has been successfully utilized for HIV testing in our study environment, it was associated with significant loss to follow up as individuals with positive test result could not be identified due to lack of identifying information such as social security numbers or government issued identification with addresses.

A full cost-effectiveness analysis was embedded within the trial and results will be reported separately. However, there are a number of factors that other researchers and frontline public health professionals should consider in trying to replicate or implement HBI to scale in other settings. They should consider the costs associated with the Mama Packs given to the pregnant women as well as the cost of integrated laboratory tests. Nevertheless, it is important to know that these costs are within the range reported by programs that demonstrated the effectiveness of conditional and unconditional cash transfers in HIV prevention.36,37 Also, the testing algorithm comprised routine tests offered to pregnant women during prenatal care. The decision to include a partial intervention (baby showers in CG churches) may have led to higher HIV screening rate than would otherwise be expected for those communities. We chose this approach because ethical concerns related to study designs (e.g., when control churches do not receive any intervention) are known to be barriers against effective implementation of congregation-based health programs. The sample size and number of study sites were based on infant baptism records, but our intervention may have impacted people outside of the study center, especially in the intervention group where onsite integrated testing was offered.

Recruitment to the trial ended in 2013, but the communities elected to continue the program due to its popularity among pregnant women, lay health advisors and priests. Each of the participating sites were provided mama packs and cost of testing for sickle cell is being defrayed by Healthy Sunrise Foundation, a non-profit organization. HIV testing is provided free through our local PEPFAR supported partner PeTR-GS. We are collecting data on HBI activities from the 40 churches that participated in the initial trial to assess sustainability. The United States International Agency for Development (USAID) and UNICEF has visited various communities where HBI is active and are in discussion with the Nigerian National AIDS Control Agency to disseminate the program to the states with the highest HV prevalence in the country.

The odds for pregnant women in control group not being tested for HIV is 11.2 times higher than pregnant women in intervention group, showing that simple culturally-adapted, community-based programs such as HBI can be used effectively to increase HIV screening among pregnant women in resource-limited setting.

Acknowledgements

The research was co-funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) under award number R01HD075050 to Echezona Ezeanolue, MD. The funding agencies played no role in the study conception, design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of the report. The corresponding author, Dr. Ezeanolue, had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. Trial was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, identifier number NCT 01795261. Full study operating procedure manual is t available on website. We are grateful to HealthySunrise Foundation, Bishop John Okoye (Catholic Bishop of Awgu diocese), Arch. Bishop Emmanuel Chukwuma (Anglican Bishop of Enugu), Bishop Callistus Onaga (Catholic Bishop of Enugu) and Arch. Bishop Amos Madu (Anglican Bishop of Oji-River). Their support was instrumental to the successful implementation of HBI. HBI implementation would not have been possible without the support and tireless effort of the priests in the participating churches. The church-based Volunteer Health Advisors took ownership of the program and made the process of recruitment and implementation smooth for our study team and participants. This study would have been impossible to conduct without the support of PeTR-GS (our PEPFAR-supported partner) staff and volunteers.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributors

EEE, MCO, COE, WY and GO contributed to the study design and trial protocol. Patient recruitment and acquisition of data was done by EEE, MCO, AO, AGO, AH, DP and JE. All authors contributed to organization, conduct of study, data analysis and interpretation of study data. EEE and JE prepared the draft manuscript and all authors subsequently reviewed the output and made revisions.

Declaration of interests

We declare that we have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Joint United Nations Programmes on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) The Gap Report. Joint United Nations Programmes on HIV/AIDS; Geneva Switzerland: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joint United Nations Programmes on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) 2013 progress report on the global plan towards the elimination of new HIV infections among children by 2015 and keeping their mothers alive. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; Geneva: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Agency for Control of AIDS (NACA) Federal Republic of Nigeria: Global AIDS response country progress report. NACA; Abuja, Nigeria: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Population Commission (NPC) [Nigeria] and ICF Macro . Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2008. Abuja, Nigeria: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pew Research Center [June 13, 2012];Tolerance and Tension: Islam and Christianity in Sub-Saharan Africa. 2010 http://www.pewforum.org/files/2010/04/sub-saharan-africa-full-report.pdf.

- 6.Swanbrow D. [Jan, 13, 2014];Study of worldwide rates of religiosity, church attendance. 1997 http://www.ns.umich.edu/Releases/1997/Dec97/chr121097a.html.

- 7.Ucheaga DN, Hartwig KA. Religious leaders' response to AIDS in Nigeria. Glob Public Health. 2010;5(6):611–25. doi: 10.1080/17441690903463619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell MK, Hudson MA, Resnicow K, Blakeney N, Paxton A, Baskin M. Church-based health promotion interventions: evidence and lessons learned. Annu Rev Public Health. 2007;28:213–34. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeHaven MJ, Hunter IB, Wilder L, Walton JW, Berry J. Health programs in faith-based organizations: are they effective? Am J Public Health. 2004;94(6):1030–6. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.6.1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drake BF, Shelton RC, Gilligan T, Allen JD. A church-based intervention to promote informed decision making for prostate cancer screening among African American men. J Natl Med Assoc. 2010;102(3):164–71. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30521-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abanilla PK, Huang KY, Shinners D, et al. Cardiovascular disease prevention in Ghana: feasibility of a faith-based organizational approach. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89(9):648–56. doi: 10.2471/BLT.11.086777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lasater T, Becker D, Hill M, Gans K. Synthesis of findings and issues from religious-based cardiovascular disease prevention trials. Annals of Epidemiology. 1997;7:S46–S53. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aguwa J. Religion and HIV/AIDS prevention in Nigeria. Crosscurrents. 2010;60(2):208–23. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muñoz-Laboy M, Garcia J, Moon-Howard J, Wilson PA, Parker R. Religious responses to HIV and AIDS: understanding the role of religious cultures and institutions in confronting the epidemic. Glob Public Health. 2011;6(Suppl 2):S127–31. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2011.602703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Donner A, Klar N. Design and analysis of cluster randomization trials in health research. Arnold; London: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ezeanolue EE, Obiefune MC, Yang W, Obaro SK, Ezeanolue CO, Ogedegbe GG. Comparative effectiveness of congregation- versus clinic-based approach to prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission: study protocol for a cluster randomized controlled trial. Implement Sci. 2013;8:62. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Altman DG, Schulz KF, Moher D, et al. The revised CONSORT statement for reporting randomized trials: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134(8):663–94. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-8-200104170-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kinuthia J, Kiarie JN, Farquhar C, et al. Uptake of prevention of mother to child transmission interventions in Kenya: health systems are more influential than stigma. J Int AIDS Soc. 2011;14:61. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-14-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aizire J, Fowler MG, Coovadia HM. Operational issues and barriers to implementation of prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) interventions in Sub-Saharan Africa. Curr HIV Res. 2013;11(2):144–59. doi: 10.2174/1570162x11311020007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Monjok E, Smesny A, Essien EJ. HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination in Nigeria: review of research studies and future directions for prevention strategies. Afr J Reprod Health. 2009;13(3):21–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hardon A, Vernooij E, Bongololo-Mbera G, et al. Women's views on consent, counseling and confidentiality in PMTCT: a mixed-methods study in four African countries. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:26. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adegbola O. Gestational age at antenatal booking in Lagos University Teaching Hospital (LUTH). Nig Q J Hosp Med. 2009;19(3):162–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bello FA, Ogunbode OO, Adesina OA, Olayemi O, Awonuga OM, Adewole IF. Acceptability of counselling and testing for HIV infection in women in labour at the University College Hospital, Ibadan, Nigeria. Afr Health Sci. 2011;11(1):30–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okonkwo KC, Reich K, Alabi AI, Umeike N, Nachman SA. An evaluation of awareness: attitudes and beliefs of pregnant Nigerian women toward voluntary counseling and testing for HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21(4):252–60. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.0065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Onah HE, Ibeziako N, Nkwo PO, Obi SN, Nwankwo TO. Voluntary counselling and testing (VCT) uptake, nevirapine use and infant feeding options at the University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;28(3):276–9. doi: 10.1080/01443610802042639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coates TJ, Kulich M, Celentano DD, et al. Effect of community-based voluntary counselling and testing on HIV incidence and social and behavioural outcomes (NIMH Project Accept; HPTN 043): a cluster-randomised trial. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2(5):e267–77. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70032-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ackerman Gulaid L, Kiragu K. Lessons learnt from promising practices in community engagement for the elimination of new HIV infections in children by 2015 and keeping their mothers alive: summary of a desk review. J Int AIDS Soc. 2012;15(Suppl 2):17390. doi: 10.7448/IAS.15.4.17390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marcos Y, Phelps BR, Bachman G. Community strategies that improve care and retention along the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV cascade: a review. J Int AIDS Soc. 2012;15(Suppl 2):17394. doi: 10.7448/IAS.15.4.17394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sekandi JN, Sempeera H, List J, et al. High acceptance of home-based HIV counseling and testing in an urban community setting in Uganda. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:730. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suthar AB, Ford N, Bachanas PJ, et al. Towards universal voluntary HIV testing and counselling: a systematic review and meta-analysis of community-based approaches. PLoS Med. 2013;10(8):e1001496. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aluisio A, Richardson BA, Bosire R, John-Stewart G, Mbori-Ngacha D, Farquhar C. Male antenatal attendance and HIV testing are associated with decreased infant HIV infection and increased HIV-free survival. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;56(1):76–82. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181fdb4c4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iwelunmor J, Ezeanolue EE, Airhihenbuwa CO, Obiefune MC, Ezeanolue CO, Ogedegbe GG. Socio-cultural factors influencing the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in Nigeria: a synthesis of the literature. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:771. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Williams MV, Palar K, Derose KP. Congregation-based programs to address HIV/AIDS: elements of successful implementation. J Urban Health. 2011;88(3):517–32. doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9526-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coleman JD, Lindley LL, Annang L, Saunders RP, Gaddist B. Development of a framework for HIV/AIDS prevention programs in African American churches. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2012;26(2):116–24. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.0163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ferris AH, McAndrew TM, Shearer D, Donnelly GF, Miller HA. Embracing the convenient care concept. Postgrad Med. 2010;122(1):7–9. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2010.01.2093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cluver L, Boyes M, Orkin M, Pantelic M, Molwena T, Sherr L. Child-focused state cash transfers and adolescent risk of HIV infection in South Africa: a propensity-score-matched case-control study. Lancet Glob Health. 2013;1(6):e362–70. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70115-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de Walque D, Dow W, Nathan R, Medlin C. Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, RESPECT Project Team. Evaluating conditional cash transfeers to prevent HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in Tanzania. 2010 Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]