Highlights

-

•

Gastric Schwannoma is a rare neoplasm of stomach.

-

•

It mimic clinically and radiologically with Gastric GIST.

-

•

Immunohistochemical study can differentiate these two tumors.

Keywords: GIST, Schwannoma, Immunohistochemichal study, CD117, S100

Abstract

Introduction

Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) is the commonest mesenchymal tumor of GI tract and 60–70% of it seen in the stomach, whereas Gastric schwannoma is a benign, slow growing and one of the rare neoplasms of stomach. Age distribution, clinical, radiological features and gross appearance of both tumors are similar.

Presentation of case

We report a rare case of gastric schwannoma in a 20-year-old girl, who underwent subtotal gastrectomy with the suspicion of a GIST preoperatively but later confirmed to be gastric schwannoma postoperatively after immunohistochemical study.

Discussion

Accordingly, the differential diagnosis for gastric submucosal mass should be gastric schwannoma. Furthermore, Gastric schwannoma is a benign neoplasm with excellent prognosis after surgical resection, whereas 10–30% of GIST has malignant behavior. Therefore, it is important to distinguish between gastric schwannoma and GIST so as to make an accurate diagnosis for optimally guide treatment options.

Conclusion

Due to the paucity of gastric schwannoma, the index of suspicion for this diagnosis is low. So it is important to include gastric schwannoma in the differential diagnosis when preoperative imaging studies reveal submucosal exophytic gastric mass and after resection of the tumor with a negative margin, it should be sent for immunohistochemical study for confirmation of diagnosis.

1. Introduction

Both Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) and Schwannoma belong to the family of mesenchymal tumors of gastrointestinal tract [1]. Among these neoplasms, GIST is the commonest and 60–70% of it seen in the stomach [2], [3]. Schwannoma is one of the rare neoplasms of GI tract and stomach is the most common site, accounting for only 0.2% of all gastric tumors and 4% of all benign gastric neoplsms [4]. Accordingly, both are taken as differential diagnosis for each other.

2. Case report

A 20-year-old female presented with symptoms of dyspepsia like early satiety, fullness of stomach after taking small meal and heart burn for last six months. Two months later she noticed a lump in the upper abdomen which was not associated with pain or vomiting. There was no other significant past medical or surgical history. On examination she was mild pallor, with a firm, non tender lump of size 6cm × 5 cm present in the epigastrium having ill defined margin, uneven surface and moving with respiration. Rest of the abdomen was normal.

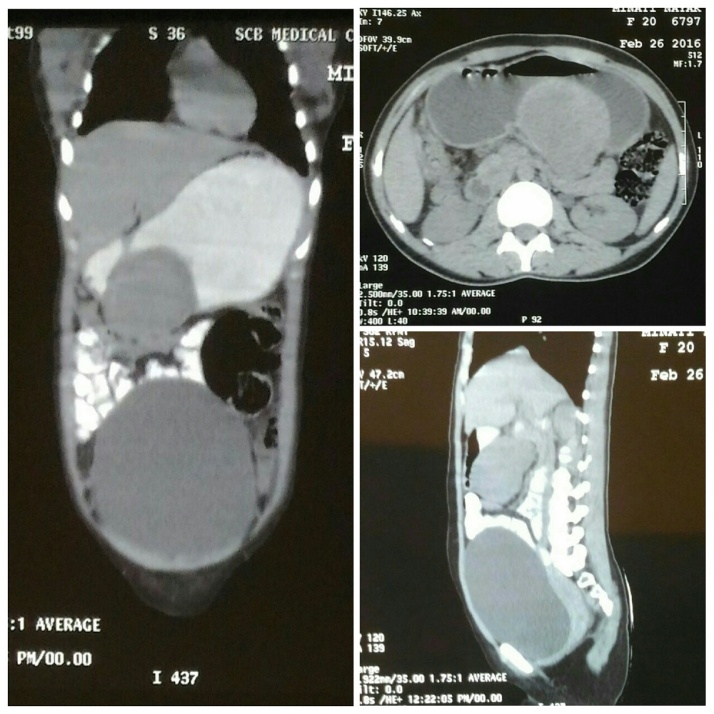

Ultrasonography (USG) of the abdomen revealed a well defined heterogeneously hypoechoiec SOL measuring 6.1cm × 5.8 cm with internal vascularity posterior to body of stomach suggestive of Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor (GIST). USG guided FNAC of the lesion revealed sheets of neoplastic cells over a hemorrhagic background suggestive of GIST. Upper GI Endoscopy was normal except for a healed duodenal ulcer scar. Contrast enhanced CT scan of the abdomen revealed intensely enhancing heterogeneous, well defined, rounded, exophytic soft tissue lesion of size 7cm × 6.2cm × 8 cm arising from greater curvature of stomach abutting the pancreas and superior mesenteric vein, possibly GIST (Fig. 1). So a pre op diagnosis, “Gastric GIST” was made on the basis of clinical and radiological finding and the patient was taken up for surgery.

Fig. 1.

Contrast enhanced CT scan of the abdomen showing intensely enhancing heterogeneous, well defined, rounded, exophytic soft tissue lesion arising from greater curvature of stomach.

With the patient in supine position the abdomen was opened through an upper-midline incision. We proceeded into the lesser sac after dividing the gastrocolic omentum and the pathology identified. An exophytic growth of size approximately 7cm × 6cm × 8 cm present involving the body and antrum of the stomach nearer to the greater curvature, which was firm in consistency and having a nodular surface (Fig. 2). Then the stomach was mobilized and a subtotal gastrectomy with omentectomy done followed by antecolic, antiperistaltic gastro-jejunostomy and jejuno-jejunostomy. The cut section of the tumor revealed yellowish white, solid, homogeneous surface (Fig. 3). The resected specimen sent for histopathological study.

Fig. 2.

Intra operative photograph of the exophytic growth involving the body and antrum of the stomach nearer to the greater curvature, having a nodular surface.

Fig. 3.

Resected omentum and subtotal gastrectomy specimen with the nodular growth which on cut section having a solid, homogenous and yellowish white surface.

The post operative period was uneventful and she discharged on 10th post op day. During the follow up after 3 months, she was absolutely asymptomatic.

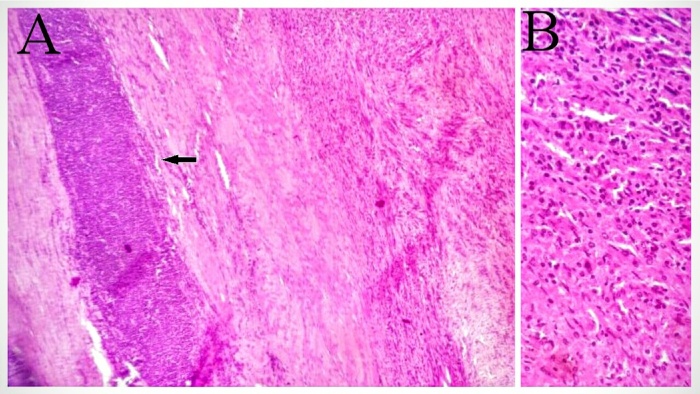

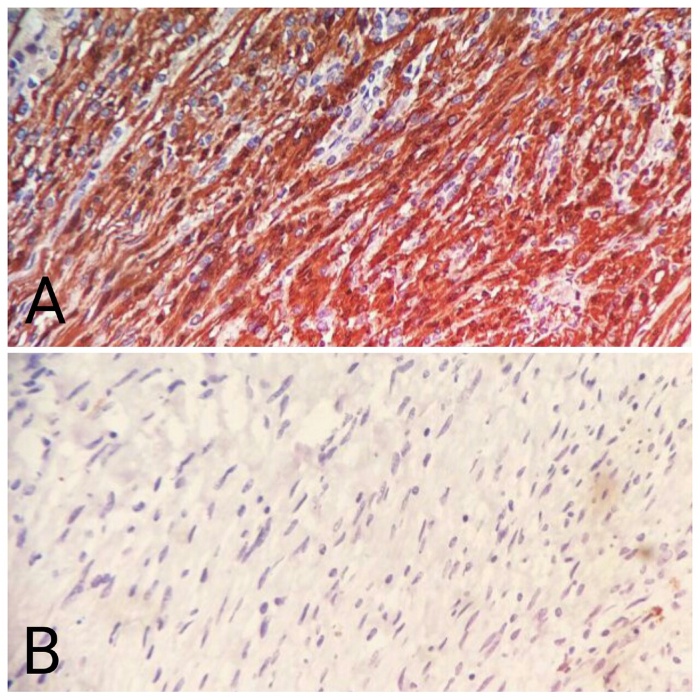

The final pathological study revealed that the resected tumor mass was arising from the layers of stomach with submucosal proliferation of spindle cells with interlacing and curling bundles with plump to slender nuclei, mild nuclear atypia and eosinophilic cytoplasm with stromal collagenisation (Fig. 4B). The tumor cell nest showed peripheral cuff of lymphoid cells (Fig. 4A) as well as scattered lymphocytes and plasma cells. There was sparse mitotic activity (<5/50 HPF). The tumor cells were immunoreactive with S100 protein (Fig. 5A), but lack of immunoreactivity with CD117 (Fig. 5B). So the histopathological features and immunohistochemical staining pattern were consistent with Gastric Schwannoma instead of GIST.

Fig. 4.

A: Proliferation of spindle cells with interlacing and curling bundles with stromal collagenisation and having peripheral cuff of lymphoid cells (arrow). (H&E × 40). B: Spindle cells having plump to slender nuclei, mild nuclear atypia and eosinophilic cytoplasm with stromal collagenisation. (H&E × 100).

Fig. 5.

A: Immunohistochemical study of tumor cells showing strong S100 positivity. B: Immunohistochemical study of tumor cells showing CD117 (c-kit) negativity.

3. Discussion

Gastrointestinal (GI) mesenchymal tumors consist mainly a spectrum of spindle cell tumors which include gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs), leiomyomas or leiomyosarcomas, and schwannomas [1]. Among these neoplasms, GISTs are the most common and 60–70% of them seen in the stomach [2], [3]. Schwannomas are benign, slow-growing, encapsulated nerve-sheath tumors arising from schwann cells, meant for the myelin sheath formation in the peripheral nervous system. They can occur anywhere along the course of the peripheral nerve, but commonly it occurs in the head and neck region, rarely in the GI tract [5]. Gastrointestinal schwannomas are usually non-encapsulated, but well demarcated tumors [6]. Within the GI tract stomach is the most common site for schwannoma accounting for only 0.2% of all gastric tumors and 4% of all benign gastric neoplsms [4]. Gastric schwannomas are usually intramural (65%), but they can be intraluminal or subserosal. The tumors arise most commonly from the body of the stomach (50%) followed by the antrum (32%) and the fundus (18%) [7].

Gastric Schwannomas occur more frequently in the fifth to sixth decades of life with a female predominance [8], [9]. They are often asymptomatic and can be discovered incidentally through upper GI endoscopy or cross-sectional imaging. The most common presenting symptom is an episode of upper GI bleeding, secondary to the growing submucosal mass compromising the blood supply to the overlying mucosa followed by ulceration secondary to ischemia or from a reduced tolerance to the gastric acidity [4], [5]. Presence of a submucosal intra luminal mass near the pylorus may cause gastric outlet obstruction. If the tumor shows exophytic growth, then patient may present with a palpable epigastric mass [10], as in our case.

Diagnostic modalities include upper GI endoscopy, computed tomography (CT) scan, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), ultrasonography, endoluminal ultrasonography (EUS) and upper gastro intestinal barium study. But all these investigations provide only limited information about the tumor. The definitive diagnosis of gastric schwannoma is determined only after histopathological and immunohistochemical examination [8]. Endoscopy helps to define the exact location of intraluminal submucosal tumors. Endoscopic needle biopsy is useful to establish a definite diagnosis of a submucosal tumor, but GISTs are having theoretical risk of hemorrhage or tumor rupture which is associated with poor prognosis [11]. On contrast enhanced CT scan, in contrast to GIST, gastric schwannomas appear mostly as homogenous, strongly contrast-enhanced tumors without signs of hemorrhage, necrosis, cystic changes or calcification [12]. MRI provides further information about the exact location of the tumor and its relation to the surrounding structures. Gastric shwannomas appear on MRI as strongly enhancing tumors. On T1 weighted images, they have low to medium signal intensity whereas high signal intensity on T2 weighted Images [13]. EUS is useful for visualizing the submucosal lesions of the stomach. The endosonographic features of schwannomas include homogeneous hypoechoic internal echoes with a marginal halo corresponding to the peritumoral lymphoid cuff in histopathological examination [14]. Transabdominal ultrasonography is helpful for larger tumors. USG-guided percutaneous core biopsy is also one of the possible method to obtain a precise preoperative diagnosis [7].

The typical histologic features of gastric schwannoma are proliferated spindle cells usually arranged in interlacing and curling bundles and presence of peritumoral lymphoid cuff [15], [16], as in our case. Gastric schwannoma differs histologically from other soft tissue schwannoma by absence of capsulation and rarity of nuclear palisading, xanthoma cells, vascular hyalinization and dilatation [15]. The histology of gastric schwannomas is similar to other mesenchymal tumours such as GIST, leiomyoma and leiomyosarcoma and these can be differentiated by the aid of Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining. Positive desmin and smooth muscle actin stains indicate leiomyoma or leiomyosarcoma, positive CD34 and CD117 (c-kit) indicate GIST and positive S100 indicate Schwannoma [1], [2], [15], [16]. Thus, in our case, the positivity for S100 and negativity for CD117 marker confirmed the diagnosis of Gastric Schwannoma.

Surgical resection is considered as the treatment of choice in patients with gastric schwannoma. Depending upon the size, location and surrounding involvement of the tumor local extirpation, wedge resection, partial, subtotal or even total gastrectomy are acceptable surgical procedures with a low recurrence rate [17]. Nowadays laparoscopic techniques are also used [18].

Both gastric schwannomas and gastric GISTs are similar in age of occurrence, clinical features, gross and histological appearance. But they differ in prognosis [1], [2], [4], [8], [9], [16]. The former is having an excellent prognosis [6], [8], [9], whereas 10–30% of GISTs are malignant [1], [2], [19]. As most of the diagnostic modalities cannot always provide enough information to differentiate between these two tumors, ultimately the definitive diagnoses of GISTs and gastric schwannomas require immunohistochemical studies which only can be performed on the surgical specimen.

4. Conclusion

Though gastric schwannoma is a rare tumor of stomach, it is important that we should consider it in the differential diagnosis when preoperative imaging studies reveal a submucosal exophytic gastric mass. According to most of the literatures it is a slow growing benign neoplasm and in contrast to GIST, rarely undergoes malignant transformation and has a good prognosis. So every submucosal mass lesion of the stomach should be sent for histopathology and immunohistochemical study after complete margin negative surgical resection for confirmation of diagnosis and further planning of treatment.

Conflict of interest

The Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical approval

Not applicable. No research study involved.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author contributions

Dr Sudhir Kumar Mohanty: the conception and design of the study, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article, revising it critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be submitted.

Dr Kumarmani Jena: the conception and design of the study, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article, revising it critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be submitted.

Dr Tanmaya Mahapatra: the conception and design of the study, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article, revising it critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be submitted.

Dr Jyoti Ranjan Dash: acquisition of data, drafting the article, final approval of the version to be submitted.

Dr Dibyasingh Meher: acquisition of data, drafting the article, final approval of the version to be submitted.

Dr Ajax John: acquisition of data, drafting the article, final approval of the version to be submitted.

Dr Manjushree Nayak: acquisition of data, done the immunohistochemical study and reporting, final approval of the version to be submitted.

Dr Shafqat Bano: acquisition of data, done the histopathological study and reporting, final approval of the version to be submitted.

Registration of research studies

No research study involved.

Guarantor of submission

The corresponding author is the guarantor of submission.

Contributor Information

Sudhir Kumar Mohanty, Email: sudhirsandhya2021@gmail.com.

Kumarmani Jena, Email: drmaniinbbsr@gmail.com.

Tanmaya Mahapatra, Email: drtanmaya1987@gmail.com, tanmaya_mahapatra2000@yahoo.com.

Jyoti Ranjan Dash, Email: drjrd88@gmail.com.

Dibyasingh Meher, Email: dibyasingh54@gmail.com.

Ajax John, Email: dr.ajaxjohn00@gmail.com.

Manjushree Nayak, Email: dr.manjushreenayak@gmail.com.

Shafqat Bano, Email: shafqat.bano@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Nishida T., Hirota S. Biological and clinical review of stromal tumors in the gastrointestinal tract. Histol. Histopathol. 2000;15(4):1293–1301. doi: 10.14670/HH-15.1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miettinen M., Majidi M., Lasota J. Pathology and diagnostic criteria of gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs): a review. Eur. J. Cancer. 2002;38:39–51. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(02)80602-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miettinen M., Sobin L.H., Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the stomach: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetics study of 1765 cases with nlong-term follow-up. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2005;29(1):52–68. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000146010.92933.de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Melvin W.S., Wilkinson M.G. Gastric schwannoma: clinical and pathologic considerations. Am. Surg. 1993;59:293–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raber M.H., des Plantes C.M.P.Z., Vink R., Klaase J.M. Gastric schwannoma presenting as an incidentaloma on CT-scan and MRI. Gastroenterol. Res. 2010;3(6):276–280. doi: 10.4021/gr245w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miettinen M., Shekitka K.M., Sobin L.H. Schwannomas in the colon and rectum: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 20 cases. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2001;25:846–855. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200107000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruneton J.N., Drouillard J., Roux P., Ettore F., Lecomte P. Neurogenic tumors of the stomach. Report of 18 cases and review of the literature. Rofo. 1983;139:192–198. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1055869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin C.S., Hsu H.S., Tsai C.H., Li W.Y., Huang M.H. Gastric schwannoma. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 2004;67:583–586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoon H.Y., Kim C.B., Lee Y.H., Kim H.G. Gastric schwannoma. Yonsei Med. J. 2008;49:1052–1054. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2008.49.6.1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Snyder R.A., Harris E., Hansen E.N., Merchant N.B., Parikh A.A. Gastric schwannoma. Am. Surg. 2008;74:753–756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arolfo S., Teggia P.M., Nano M. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: thirty years experience of an Institution. World J. Gastroenterol. 2011;17:1836–1839. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i14.1836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levy A.D., Quiles A.M., Miettinen M., Sobin L.H. Gastrointestinal schwannomas: CT features with clinicopathologic correlation. Am. J. Roentenol. 2005;184:797–802. doi: 10.2214/ajr.184.3.01840797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karabulut N., Martin D.R., Yang M. Gastric schwannoma: MRI findings. Br. J. Radiol. 2002;75:624–626. doi: 10.1259/bjr.75.895.750624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jung M.K., Jeon S.W., Cho C.M., Tak W.Y., Kweon Y.O., Kim S.K., Choi Y.H., Bae H.I. Gastric schwannomas: endosonographic characteristics. Abdom. Imaging. 2008;33:388–390. doi: 10.1007/s00261-007-9291-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Voltaggio L., Murray R., Lasota J., Miettinen M. Gastric schwannoma: a clinicopathologic study of 51 cases and critical review of the literature. Hum. Pathol. 2012;43:650–659. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2011.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sarlomo-Rikala M., Miettinen M. Gastric Schwannoma: a clinico-pathological analysis of six cases. Histopathology. 1995;27:355–360. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1995.tb01526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bandoh T., Isoyama T., Toyoshima H. Submucosal tumors of the stomach: a study of 100 operative cases. Surgery. 1993;113:498–506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Basso N., Rosato P., De Leo A., Picconi T., Trentino P., Fantini A. Laparoscopic treatment of gastric stromal tumors. Surg. Endosc. 2000;14:524–526. doi: 10.1007/s004640000021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perez E.A., Livingstone A.S., Franceschi D. Current incidence and outcomes of gastrointestinal mesenchymal tumors including gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2006;202(4):623–629. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]