Highlights

-

•

An intrauterine contraceptive device (IUD) is a long acting, highly effective, economic and reversible method of contraception.

-

•

Common complications include failed insertion, pain, vasovagal reactions, infection, menstrual abnormalities and expulsion. Although uncommon, uterine embedment and perforation may occur.

-

•

The current paper reported the first case of migrated IUCD to inguinal cannel.

Keywords: Intrauterine device, Migration, Perforation, Inguinal canal

Abstract

Introduction

A large number of complications are reported with the use of IUD. Migration to inguinal region has not been mentioned in literature. We report a rare case of migrated IUD to inguinal canal.

Case report

A 25-year-old lady presented with a painfull mass in the left inguinal region. Diagnostic work up showed migrated IUD to inguinal region. Operation was done and the impacted IUD with surrounding granuloma was retrieved.

Discussion

When the string of the IUD is no longer visible at the external os of the cervix, radiological scan must be performed, this should begin with a sonographic examination and plain abdominal radiography may be used to localize the IUD.

Conclusion

IUD Migration may occur to unusual area and perforation can be misdiagnosed as non-witnessed expulsion.

1. Introduction

An intrauterine contraceptive device (IUD) is a long acting, highly effective, economic and reversible method of contraception used worldwide with almost 108 million users in 1999 [1]. Currently, the most used devices are either Copper IUD or Mirena (Levonorgestrel) IUD [1], [2]. Common complications include failed insertion, pain, vasovagal reactions, infection, menstrual abnormalities and expulsion. Although uncommon, uterine embedment (whereby the IUD is located in the myometrium) and perforation (whereby any or the entire IUD is located beyond the uterine serosa) occur in approximately 1 in 1000 insertions [1].

Perforation of the uterus, although rare, is a serious complication. A literature review of the 18 years until 1999 showed 165 reported cases distributed at the following sites: the omentum (27%), the rectosigmoid (26%), the peritoneum (24%), the appendix (0.05%), the small bowel (0.01%), the adnexa and the iliac vein (0.006%) [2], [3], [4], migration to the bladder is uncommon and has been reported in only 31 cases [4], [5], [6]. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of migrated IUD to inguinal region. The work has been written in accordance of Care guide line [7].

2. Case report

A 25-year-old lady presented to our department with left painful inguinal mass of six months duration. The pain was increasing with forward, hip flexion and local pressure, no significant urinary or gastrointestinal symptoms. Obstetric history revealed (Gravida 3, Para 3 and Abortion 0), all labors were normal vaginal deliveries, three months after her second delivery, IUD has been inserted, post procedure ultrasonography showed the IUD in proper position, but four months later she got unplanned pregnancy where ultrasonography this time failed to localize the missed IUD inside or outside the uterine cavity. It had been diagnosed as non-witnessed expulsion. The pregnancy proceeded uneventfully. Four months after delivery, another IUD had been inserted for her.

On examination, the patient had a left inguinal firm to hard mass, 4×4 cm in size, located just above and laterals to the level of the internal inguinal ring. Negative cough impulse, no palpable regional lymph nodes.

Ultrasonography showed a complex cystic mass 3×3 cm at the mid inguinal canal, CT scan confirmed the mass to be a migrated IUD (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Abdomino-pelvic contrast enhanced computed tomography showing a cystic mass with the IUD (arrowed) in the extraperitoneal fat at the left side of the pelvis.

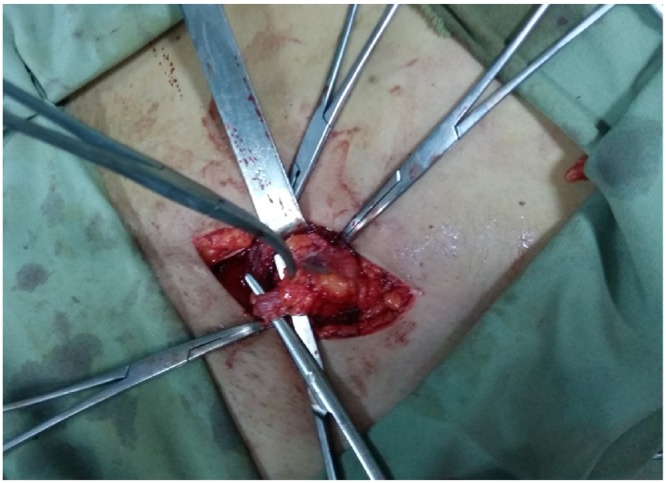

Under general anesthesia, left inguinal incision done, dissection and isolation of the round ligament done (Fig. 2). There was a hard mass just lateral to the deep inguinal ring adherent to the round ligament with the IUD string and main stalk were visible within the mass (Fig. 3), dissection completed from the surrounding tissue and the underlying adhesion of wrapped omentum, the mass totally excised (Fig. 4). The patient referred to gynecologist for removal of the second IUD.

Fig. 2.

Isolation of the round ligament and the mass.

Fig. 3.

The IUD string and main stalk are visible.

Fig. 4.

the mass totally excised with IUD inside.

3. Discussion

The exact mechanism by which IUD perforations occur is unclear and various etiologic theories exist. It may occur at the time of insertion (may be from sound dilatation), and the device is released beyond the serosa. Transmural migration may happen after a correct insertion. Finally, embedment may occur at the time of insertion, which predisposes to trans-mural migration and ultimate perforation [1], [3], [8]. Other rare mechanisms have been reported, including trans-tubal migration and trans-cervical perforation [1], [8]. If the string of an IUD could not be recognized by the patient or the examiner, there are three explanations: The IUD is still in the uterus, but the strings are broken or curled up, the IUD has been expelled or the uterus is completely or partially perforated and the IUD is in the uterine wall or the abdominal cavity [8]. In this case, expulsion was suspected as pregnancy occurred and the ultrasonography failed to localize the device. The risk factors for uterine perforation include: type of IUD (copper containing devices seems to cause larger number of perforation), Insertion technique, lack of clinical experience, immobile uterus, retroverted uterus, myometrial defects, either pre-existing or iatrogenic, lactation, the IUD being placed <6months post-partum, Nulliparity and previous miscarriage [1], [3], [4], [5], [8], [9]. The present case had history of copper IUD insertion 4 months after delivery. Symptoms of perforation and/or embedment range from asymptomatic to severe abdominal pain and abnormal vaginal bleeding, rarely distant intra-abdominal migration may result in injury to various pelvic and abdominal structures [1]. Our patient presented with painful inguinal mass for 6 month duration.

When the string of the IUD is no longer visible at the external os of the cervix, radiological scan must be performed, this should begin with a sonographic examination (trans-abdominal and/or trans-vaginal) [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [8], [10]

All IUDs are radio-opaque; therefore, plain abdominal radiography may be used to localize the IUD [4], [10], [11]. Single photon emission computed tomography with computed tomogramphy have a major role in achieving an exact diagnosis in difficult cases [11]. This case presented with inguinal mass and the ultrasonography showed a cystic lesion that necessitated further evaluation by CT scan which showed the exact site of the migrated IUD near the anterior abdominal wall at the level of left inguinal canal (Fig. 1). This finding and Concerns about extensive adhesions as well as lack of laparoscopic experience at our center had leaded us to prefer open technique for IUD retrieval and the device removed successfully. This procedure looks to have shorter duration, less need for equipments (more cost effective) and fewer major complications than laparoscopic removal [2], [3], [9].

4. Conclusion

IUDs are safe and effective form of reversible contraception; however migration may occur to unusual area and perforation can be misdiagnosed as non witnessed expulsion. We recommend full clinical and radiological assessment of lost IUDs.

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

Approval has been given by Ethical committee of Sulaymaiyah university. No:40. 2016.

Consent

Informed consent has been taken from the patient.

Author contribution

Design and idea: Ismaeel Aghaways, Saman Wahid Anwer, Rawa Hama Ghareeb Ali, Falah Sabir and Fahmi H. Kakamad.

Drafting: Saman Wahid Anwer, Rawa Hama Ghareeb Ali, Ismaeel Aghaways.

Data aquision: Rawa Hama Ghareeb Ali, Saman Wahid Anwer, Fahmi H. Kakamad.

Final revision: Ismaeel Aghaways, Saman Wahid Anwer, Rawa Hama Ghareeb Ali, Falah Sabir and Fahmi H. Kakamad.

Registration of research studies

Research registry 1508.

Guarantor

The corresponding author is the guarantor of submission.

References

- 1.Ferguson C.A., Costescu D., Jamieson M.A., Jong L. Transmural migration and perforation of a levonorgestrel intrauterine system: a case report and review of the literature. Contraception. 2016;83:81–86. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2015.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ertopcu K., Nayki C., Ulug P., Nayki U., Gultekin E., Donmez A., Yildirim Y. Surgical removal of intra-abdominal intrauterine devices at one center in a 20-year period. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2015;128:10–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2014.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miranda L., Settembre A., Cuccurullo P. Laparoscopic removal of an intraperitoneal translocated intrauterine contraceptive device. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care. 2003;8:122–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Esfahani M.R., Abdar A. Unusual migration of intrauterine device into bladder and calculus formation. Urol. J. (Tehran) 2007;4:49–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mudassir Maqbool Wani, Tarique Hussain Ashraf, Adil Rashid Shah Intrauterine contraception device migration presenting as an abdominal mass. J. Case Rep. 2015;5(1):156–159. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guvel Sezgin, Tekin M. Ilteris, Ferhat Kilinc. Bladder stones around a migrating and missed intrauterine contraceptive device. Int. J. Urol. 2001;8:78–79. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2042.2001.00249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gagnier J., Kienle G., Altman D.G., Moher D., Sox H., Riley D.S., The CARE group The CARE guidelines: consensus-based clinical case report guideline development. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2016;67:46––51. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carmody K., Schwartz B., Chang A. Extrauterine migration of a MIRENA intrauterine device: a case report. J. Emergency Med. 2011;41(2):165–166. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2010.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ozdemir O., Sari M., Sen E. Intrauterine contraceptive device migration to the sigmoid colon: case report. Medicine Science. 2015;4(2):2257–2262. [Google Scholar]

- 10.El-khalek A.M.A., Zaghloul K., Samy M. A rare site of intrauterine contraceptive device migration. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2016;198:156–178. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2015.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morland D., Mathelin C., Wattiez A. Bone single photon emission computed tomography with computed tomography disclosing chronic uterine perforation with intrauterine device migration into the anterior wall of the bladder: a case report. J. Med. Case Rep. 2013;7:154. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-7-154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]