To the editor:

Myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) comprise a heterogeneous group of hematologic disorders characterized by clonal overproduction of differentiated myeloid cells, propensity to thrombosis, hemorrhage, and increased risk of leukemia. Three MPN subtypes, polycythemia vera (PV), essential thrombocythemia (ET), and primary myelofibrosis (PMF) are considered as the “classical BCR-ABL1–negative MPNs,” and they share many clinical and molecular features. Although most cases of MPN are sporadic, several previous studies have shown familial clustering of the disease1-3 and increased risk of MPN in relatives.4 Somatic mutations have been associated with MPN, most notably disease causing, mutually exclusive mutations in Janus kinase 2 (JAK2), calreticulin (CALR), and myeloproliferative leukemia (MPL) genes. Somatic JAK2 mutations are present in ∼60% of MPN cases,5,6 MPL mutations occur somatically in ∼1% to 5% of cases,7 and somatic CALR mutations are found in ∼20% to 30% of ET and PMF.8,9 Familial MPN is clinically indistinguishable from sporadic MPN, and displays frequent somatic JAK2 and CALR mutations.2,3,10-12 Other genes that frequently mutate somatically in MPN, such as TET2,13 DNMT3A,14 and ASXL1,15 do not significantly contribute to familial MPN and in the majority of familial cases the causative germline mutation is unknown.16,17

The role of common germline variants in MPN predisposition has been established. Specifically, the JAK2 “GGCC” haplotype increases the risk to develop JAK2-mutant MPN by several fold.18 Another germline variant in telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) (rs2736100) increases the risk of all molecular subtypes of MPN by approximately twofold.19,20 Both of these single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) contribute to familial clustering of the disease, although they can explain only a minor proportion of it.19 Recently several additional common variants conferring susceptibility to MPN have been identified.21

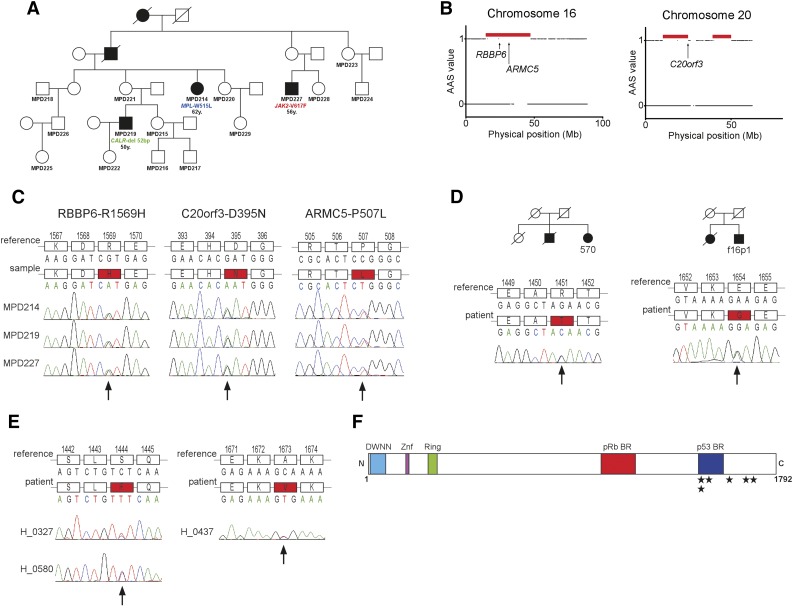

In order to identify the germline mutation predisposing to MPN, we studied an Australian pedigree of English ancestry (Northern England) with 5 members in 4 generations diagnosed with MPN. DNA was available from 3 affected members (Figure 1A). Each of the 3 members of the family had a different MPN-specific somatic mutation (JAK2-V617F, MPL-W515L, and CALR-type 1; Figure 1A). To map the candidate disease loci in the pedigree, we applied a nonparametric algorithm, segregation exclusion analysis (see supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood Web site), and identified 12 shared genomic regions with a total size of 217.87 Mb among the 3 affected subjects (Figure 1B; supplemental Table 1). As one of these genomic regions was likely to carry the disease-causing mutation, we next applied exome sequencing. After reference alignment, a number of filtering criteria were applied to the detected variants (supplemental Figure 2). We performed Sanger sequencing of all the 18 final candidate variants and confirmed DNA variants segregating with the disease in three genes (RBBP6, C20orf3, and ARMC5) (Figure 1C; supplemental Table 2).

Figure 1.

Identification of the germline mutation causing MPNs in the Australian family and screening in other MPN cases. (A) Family tree of the Australian family. The patients with mutations in JAK2, MPL, and CALR are marked. Below the mutations, the age at diagnosis is indicated. (B) Genomic regions shared by the 3 affected members in the family identified by the segregation exclusion analysis (red horizontal bars). Arrows indicate the physical position of the candidate genes RBBP6, ARMC5, and C20orf3. (C) Validation of the mutations in RBBP6, ARMC5, and C20orf3 segregating with the disease in the pedigree. The locations of mutations are marked with an arrow. (D) The RBBP6 mutations found in familial cases of MPNs. The respective family trees are shown. For both families, DNA was available only from 1 member and the segregation of the mutation with MPN was not possible to establish. (E) The 2 unique RBBP6 mutations found in 3 sporadic cases of MPNs. (F) The schematic structure of the RBBP6 protein with known and predicted domains. The locations of the detected mutations that are not observed in healthy controls are shown with stars. AAS, absence of allele-sharing; BR, binding region; DWNN, domain with no name; Mb, megabase pair; Znf, zinc finger domain.

To identify which of the RBBP6, C20orf3, and ARMC5 variants is the one predisposing to MPN, we examined healthy subjects for the presence of the candidate variants. Based on this analysis, ARMC5-P507L was excluded due to 7% frequency in healthy controls, whereas RBBP6-R1569H and C20orf3-D395N were not found in any of the over 700 healthy controls.

Next, we sequenced the exons carrying the identified RBBP6 and C20orf3 mutations in an additional 66 MPN families. This analysis yielded two unique mutations in RBBP6 (E1654G and R1451T; Figure 1D) and 1 polymorphism in C20orf3 (P406L) present in 4% of the healthy subjects. Unfortunately, for both familial cases with the RBBP6 mutation, the DNA sample was available from only 1 affected member; therefore we could not obtain data on the mutation segregation with MPN for these 2 additional families. We used Polyphen 2 and SIFT mutation prediction tools to assess the possible effects of the mutations on protein function. RBBP6-R1569H is predicted to be damaging by both tools, whereas C20orf3-D395N mutation is benign (supplemental Table 3). In conclusion, C20orf3 is unlikely to be involved in familial MPN, whereas RBBP6 mutations remain strong candidates for familial predisposition to MPN.

Due to the low penetrance associated with RBBP6 mutations, establishing the family history of MPN may often be difficult. Therefore, we screened for RBBP6 mutations in 490 sporadic MPN cases. In this analysis, we identified 2 unique germline mutations (S1444F and A1673V) in 3 apparently unrelated subjects and 1 polymorphism (I1661V) present in 0.5% of healthy controls (Table 1; Figure 1E). Overall, we identified 5 different germline RBBP6 mutations associated with MPN and not detected in the general population (Table 1; Figure 1F).

Table 1.

Summary of unique RBBP6 variants in familial and sporadic MPN cases

| Pedigree | Sample | Diagnosis | JAK2/MPL/CALR | cDNA change | Amino acid change | Polyphen 2 score | Polyphen 2 prediction | In healthy controls |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | MPD214 | ET | MPL-W515L | c.4706G>T | R1569H | 0.766 | Possibly damaging | 0/715 |

| MPD219 | PMF | CALR-Type 1 | c.4706G>T | R1569H | — | — | — | |

| MPD227 | PMF | JAK2-V617F | c.4706G>T | R1569H | — | — | — | |

| 2 | f16p1 | PMF | JAK2-V617F | c.4961A>G | E1654G | 0.375 | Benign | 0/649 |

| 3 | 570 | PMF | JAK2-V617F | c.4352G>C | R1451T | 0.942 | Probably damaging | 0/642 |

| Sporadic | H_0327 | PV | JAK2-Ex12del | c.4331C>T | S1444F | 0.976 | Probably damaging | 0/650 |

| Sporadic | H_0580 | ET | JAK2-V617F | c.4331C>T | S1444F | 0.976 | Probably damaging | 0/650 |

| Sporadic | H_0437 | PV | — | c.5018C>T | A1673V | 0.010 | Benign | 0/607 |

cDNA, complementary DNA; del, deletion; Ex12del, exon 12 deletion E543-D544.

Apart from the 3 affected members, 8 additional healthy family members carried RBBP6-R1569H in the Australian pedigree, consistent with the expected low penetrance.16 Because common germline SNPs have been shown to contribute to familial MPN,19 we checked all members of the family for JAK2 GGCC haplotype and the rs2736100_C risk variant in TERT (supplemental Table 4). As expected, from the affected members only the one with JAK2-V617F mutation was heterozygous for JAK2 GGCC haplotype, whereas 2 affected members were heterozygous for TERT risk variant and the third one was homozygous for the TERT risk allele. Although it is not possible to draw any solid conclusions based on a single family, we noticed a trend in JAK2 GGCC haplotype and TERT SNP distribution similar to the pattern we observed in our previous study.19 The risk allele frequencies for both JAK2 GGCC haplotype and TERT rs2736100 were higher in RBBP6-R1569H mutant MPN patients compared with RBBP6-R1569H mutant unaffected members (16.67% vs 6.25% for JAK2 GGCC haplotype, 66.67% vs 50.00% for TERT SNP).

We have identified germline RBBP6 mutations in ∼5% of familial MPN cases (3/67) and in ∼0.6% of sporadic cases (3/490) where family history is unknown. The low penetrance present in MPN pedigrees suggests that the disease is triggered by some stochastic factors, perhaps the acquisition of somatic mutations. In addition, common germline predisposition factors, such as JAK2 GGCC haplotype and TERT rs2736100 SNP, seem to have an additive effect on the MPN risk in RBBP6 mutation carriers.

RBBP6 is a RING finger E3 ubiquitin ligase located in the nucleus. It has been reported to ubiquitinate and degrade p53, in association with MDM2.22 Because the RBBP6 mutations identified in our study were all located in the vicinity of its p53-binding domain (Figure 1F), they may affect p53 functions. It is likely that mutant RBBP6 causes an elevation in somatic mutagenesis rates through inhibition of p53 function and deregulation of cell cycle. The existence of somatic mutations in three hallmark MPN genes (JAK2, MPL, and CALR) in a single family might be due to elevated mutagenesis in RBBP6 mutation carriers. Alternatively, RBBP6 mutations might enhance JAK-STAT signaling by a yet unknown mechanism, providing “fertile ground” for MPN development.

We cannot completely exclude the possibility that another unidentified mutation might be segregating with MPN phenotype in the family we studied due to insufficient coverage of some genomic regions by exome sequencing or the mutation being located in a noncoding region. However, our data suggests that RBBP6 is a candidate gene for MPN susceptibility in a subset of pedigrees with familial MPN. The question how RBBP6 mutations predispose predominantly to MPN phenotype remains elusive. There are examples of germline mutations in cancer-associated genes causing a specific familial phenotype, eg, retinoblastoma23 (RB1), neurofibromatosis24 (NF1), melanoma25 (CDKN2A), and others. Similarly, germline RBBP6 mutations may predominantly predispose toward myeloproliferative phenotypes.

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

Authorship

Acknowledgments: The studies performed in Vienna were supported by grants from the Austrian Science Fund (FWF2812-B20 and FWF4702-B20) and the MPN Research Foundation. E.H. was supported by the Ray and Bill Dobney Foundation. Studies performed in Pavia were funded by a grant from Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC, Milano) “Special Program Molecular Clinical Oncology 5 × 1000” to AIRC-Gruppo Italiano Malattie Mieloproliferative, project number 1005. E.R. received funding from the Italian Society of Experimental Hematology and the Italian Ministry of Health for Young Investigators.

Contribution: A.S.H. and R.K. conceived and designed the experiments; A.S.H., R.G., C.K., R.J., T.K., T.B., J.D.M.F., B.G., A.C.M., K.P., and K.L.B. performed the experiments; A.S.H., R.G., C.K., A.S., R.J., T.K., D.C., J.D.M.F., F.P.B., J.C., K.L.B., and R.K. analyzed the data; A.S.H., A.S., F.P.B., and J.C. performed the statistical analysis; H.G., E.R., F.P., D.P., R.H., J.C., K.L.B., G.S.-F., M.C., E.H., and R.K. contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools; A.S.H. and R.K. wrote the paper; and all authors contributed to the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Robert Kralovics, CeMM Research Center for Molecular Medicine of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Lazarettgasse 14, AKH BT 25.3, 1090 Vienna, Austria; e-mail: rkralovics@cemm.oeaw.ac.at.

References

- 1.Kralovics R, Stockton DW, Prchal JT. Clonal hematopoiesis in familial polycythemia vera suggests the involvement of multiple mutational events in the early pathogenesis of the disease. Blood. 2003;102(10):3793–3796. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rumi E, Passamonti F, Pietra D, et al. JAK2 (V617F) as an acquired somatic mutation and a secondary genetic event associated with disease progression in familial myeloproliferative disorders. Cancer. 2006;107(9):2206–2211. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bellanné-Chantelot C, Chaumarel I, Labopin M, et al. Genetic and clinical implications of the Val617Phe JAK2 mutation in 72 families with myeloproliferative disorders. Blood. 2006;108(1):346–352. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-12-4852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Landgren O, Goldin LR, Kristinsson SY, Helgadottir EA, Samuelsson J, Björkholm M. Increased risks of polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia, and myelofibrosis among 24,577 first-degree relatives of 11,039 patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms in Sweden. Blood. 2008;112(6):2199–2204. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-143602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.James C, Ugo V, Le Couédic JP, et al. A unique clonal JAK2 mutation leading to constitutive signalling causes polycythaemia vera. Nature. 2005;434(7037):1144–1148. doi: 10.1038/nature03546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kralovics R, Passamonti F, Buser AS, et al. A gain-of-function mutation of JAK2 in myeloproliferative disorders. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(17):1779–1790. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pikman Y, Lee BH, Mercher T, et al. MPLW515L is a novel somatic activating mutation in myelofibrosis with myeloid metaplasia. PLoS Med. 2006;3(7):e270. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klampfl T, Gisslinger H, Harutyunyan AS, et al. Somatic mutations of calreticulin in myeloproliferative neoplasms. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(25):2379–2390. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1311347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nangalia J, Massie CE, Baxter EJ, et al. Somatic CALR mutations in myeloproliferative neoplasms with nonmutated JAK2. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(25):2391–2405. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1312542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lundberg P, Nienhold R, Ambrosetti A, Cervantes F, Pérez-Encinas MM, Skoda RC. Somatic mutations in calreticulin can be found in pedigrees with familial predisposition to myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood. 2014;123(17):2744–2745. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-01-550863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maffioli M, Genoni A, Caramazza D, et al. Looking for CALR mutations in familial myeloproliferative neoplasms. Leukemia. 2014;28(6):1357–1360. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rumi E, Harutyunyan AS, Pietra D, et al. Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro Gruppo Italiano Malattie Mieloproliferative Investigators. CALR exon 9 mutations are somatically acquired events in familial cases of essential thrombocythemia or primary myelofibrosis. Blood. 2014;123(15):2416–2419. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-01-550434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delhommeau F, Dupont S, Della Valle V, et al. Mutation in TET2 in myeloid cancers. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(22):2289–2301. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ley TJ, Ding L, Walter MJ, et al. DNMT3A mutations in acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(25):2424–2433. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1005143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carbuccia N, Murati A, Trouplin V, et al. Mutations of ASXL1 gene in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Leukemia. 2009;23(11):2183–2186. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olcaydu D, Rumi E, Harutyunyan A, et al. The role of the JAK2 GGCC haplotype and the TET2 gene in familial myeloproliferative neoplasms. Haematologica. 2011;96(3):367–374. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2010.034488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saint-Martin C, Leroy G, Delhommeau F, et al. French Group of Familial Myeloproliferative Disorders. Analysis of the ten-eleven translocation 2 (TET2) gene in familial myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood. 2009;114(8):1628–1632. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-01-197525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olcaydu D, Harutyunyan A, Jäger R, et al. A common JAK2 haplotype confers susceptibility to myeloproliferative neoplasms. Nat Genet. 2009;41(4):450–454. doi: 10.1038/ng.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jäger R, Harutyunyan AS, Rumi E, et al. Common germline variation at the TERT locus contributes to familial clustering of myeloproliferative neoplasms. Am J Hematol. 2014;89(12):1107–1110. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oddsson A, Kristinsson SY, Helgason H, et al. The germline sequence variant rs2736100_C in TERT associates with myeloproliferative neoplasms. Leukemia. 2014;28(6):1371–1374. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tapper W, Jones AV, Kralovics R, et al. Genetic variation at MECOM, TERT, JAK2 and HBS1L-MYB predisposes to myeloproliferative neoplasms. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6691. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li L, Deng B, Xing G, et al. PACT is a negative regulator of p53 and essential for cell growth and embryonic development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(19):7951–7956. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701916104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee WH, Bookstein R, Hong F, Young LJ, Shew JY, Lee EY. Human retinoblastoma susceptibility gene: cloning, identification, and sequence. Science. 1987;235(4794):1394–1399. doi: 10.1126/science.3823889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wallace MR, Marchuk DA, Andersen LB, et al. Type 1 neurofibromatosis gene: identification of a large transcript disrupted in three NF1 patients. Science. 1990;249(4965):181–186. doi: 10.1126/science.2134734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hussussian CJ, Struewing JP, Goldstein AM, et al. Germline p16 mutations in familial melanoma. Nat Genet. 1994;8(1):15–21. doi: 10.1038/ng0994-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]