Abstract

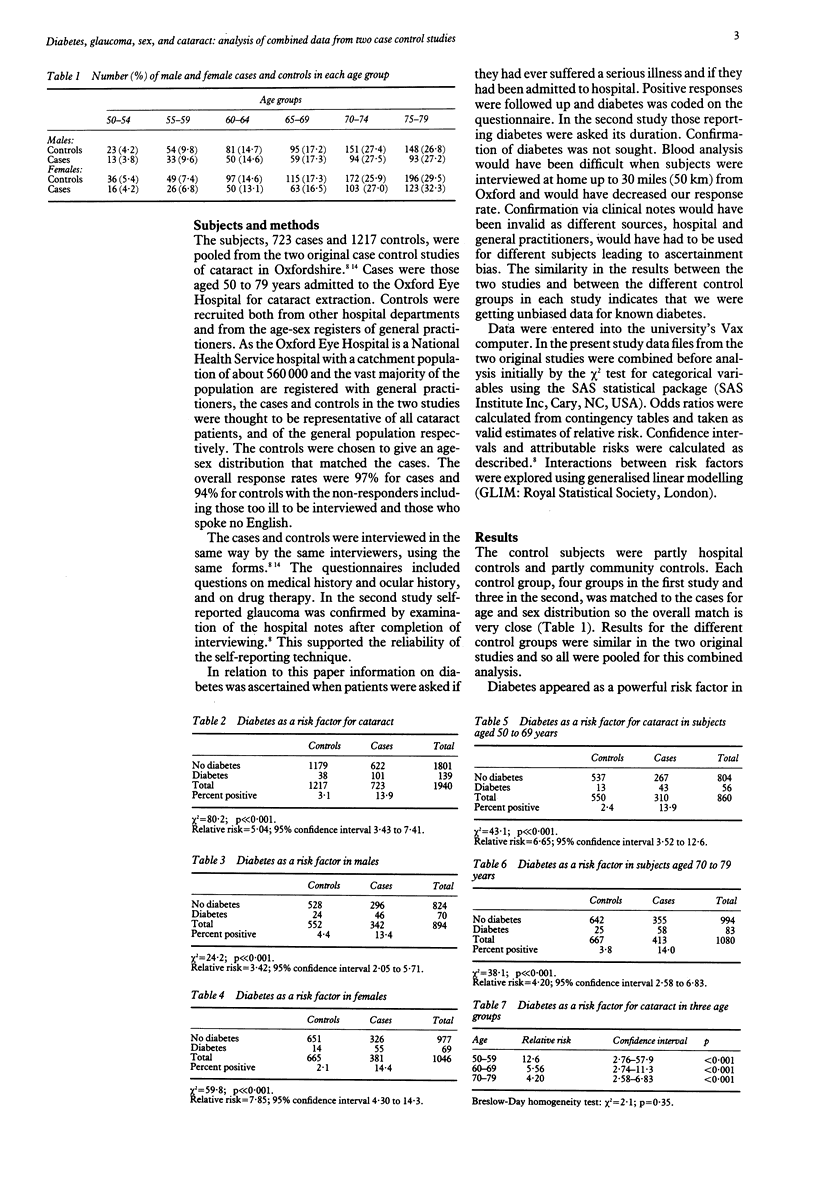

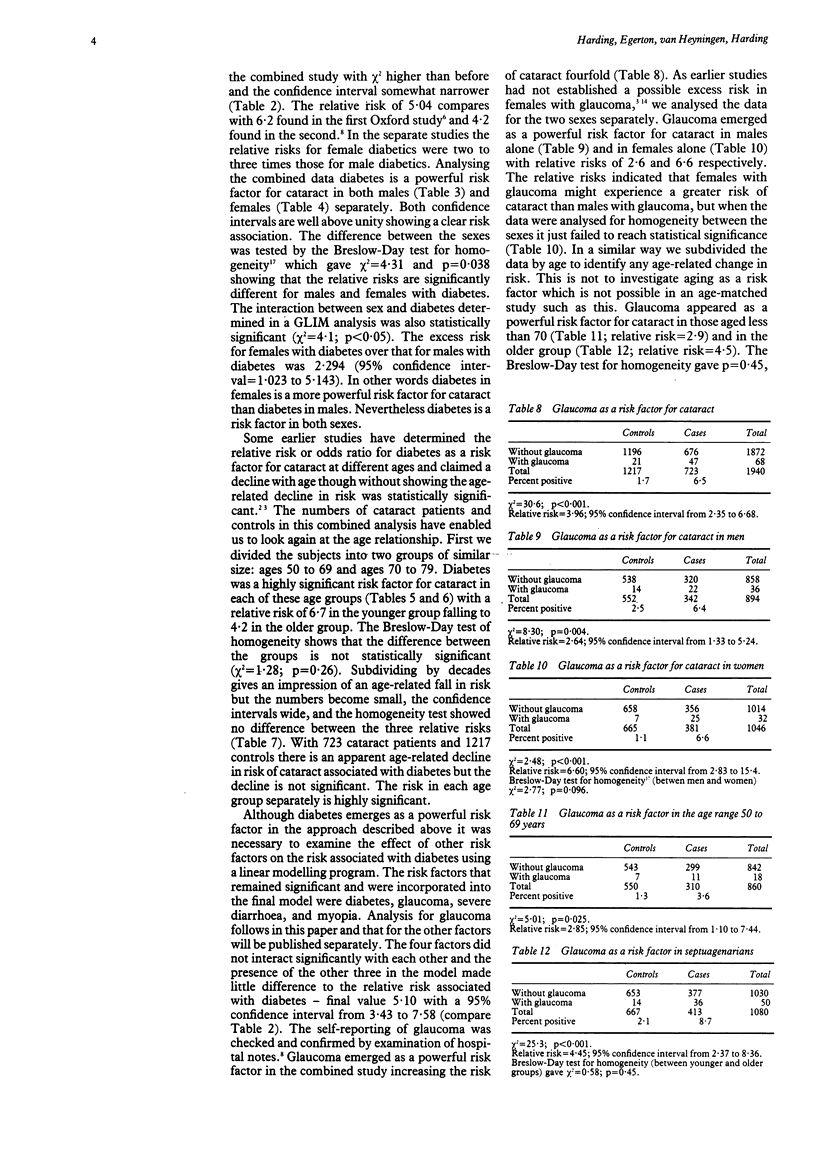

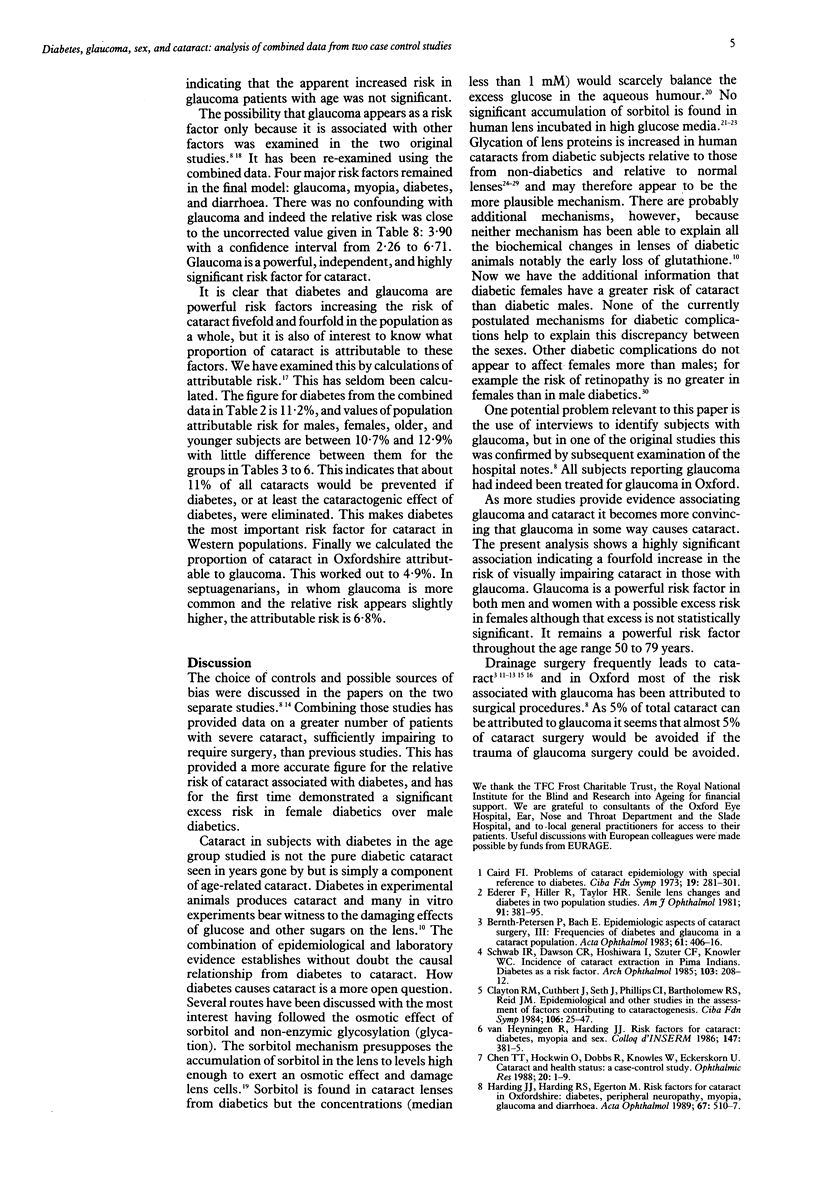

Data from two case control studies in Oxfordshire were combined and analysed. The combined study covered 1940 subjects, 723 cases, and 1217 controls, between the ages of 50 and 79 with a response rate of 97% for cases and 94% for controls. Diabetes was shown to be a powerful and highly significant risk factor for cataract with a relative risk of 5.04. More than 11% of cataracts in Oxfordshire are attributable to diabetes. The relative risk did not increase significantly with age within the range 50 to 79 years but was higher in females than in males. For females with diabetes the relative risk was 7.85 with 95% confidence interval from 4.30 to 14.3 compared with 3.42 with confidence interval from 2.05 to 5.71 for males with diabetes. Diabetes remained a powerful risk factor when other identified risk factors had been controlled for. No known mechanism for the development of diabetic complications provides an explanation for the excess risk in females. Combination of the two studies led to better estimates of the relative risk of glaucoma as a risk factor for cataract (3.96 with 95% confidence interval from 2.35 to 6.68). The relative risk appeared to be greater in women than in men but this difference was not statistically significant. There was no significant change in risk with age. Glaucoma is a powerful and independent risk factor for cataract in both sexes and may be responsible for 5% of all cataracts in our area.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Ansari N. H., Awasthi Y. C., Srivastava S. K. Role of glycosylation in protein disulfide formation and cataractogenesis. Exp Eye Res. 1980 Jul;31(1):9–19. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(80)90086-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernth-Petersen P., Bach E. Epidemiologic aspects of cataract surgery. III: Frequencies of diabetes and glaucoma in a cataract population. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1983 Jun;61(3):406–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1983.tb01439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T. T., Hockwin O., Dobbs R., Knowles W., Eckerskorn U. Cataract and health status: a case-control study. Ophthalmic Res. 1988;20(1):1–9. doi: 10.1159/000266246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke M. P., Vernon S. A., Sheldrick J. H. The development of cataract following trabeculectomy. Eye (Lond) 1990;4(Pt 4):577–583. doi: 10.1038/eye.1990.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton R. M., Cuthbert J., Seth J., Phillips C. I., Bartholomew R. S., Reid J. M. Epidemiological and other studies in the assessment of factors contributing to cataractogenesis. Ciba Found Symp. 1984;106:25–47. doi: 10.1002/9780470720875.ch3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ederer F., Hiller R., Taylor H. R. Senile lens changes and diabetes in two population studies. Am J Ophthalmol. 1981 Mar;91(3):381–395. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(81)90293-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding J. J., Harding R. S., Egerton M. Risk factors for cataract in Oxfordshire: diabetes, peripheral neuropathy, myopia, glaucoma and diarrhoea. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1989 Oct;67(5):510–517. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1989.tb04101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kador P. F., Kinoshita J. H. Diabetic and galactosaemic cataracts. Ciba Found Symp. 1984;106:110–131. doi: 10.1002/9780470720875.ch7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasai K., Nakamura T., Kase N., Hiraoka T., Suzuki R., Kogure F., Shimoda S. I. Increased glycosylation of proteins from cataractous lenses in diabetes. Diabetologia. 1983 Jul;25(1):36–38. doi: 10.1007/BF00251894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein R., Klein B. E., Moss S. E., Davis M. D., DeMets D. L. The Wisconsin epidemiologic study of diabetic retinopathy. II. Prevalence and risk of diabetic retinopathy when age at diagnosis is less than 30 years. Arch Ophthalmol. 1984 Apr;102(4):520–526. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1984.01040030398010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laatkainen L. Late results of surgery on eyes with primary glaucoma and cataract. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1971;49(2):281–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1971.tb00952.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman S., Moran M. Sorbitol generation and its inhibition by Sorbinil in the aging normal human and rabbit lens and human diabetic cataracts. Ophthalmic Res. 1988;20(6):348–352. doi: 10.1159/000266750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang J. N., Hershorin L. L., Chylack L. T., Jr Non-enzymatic glycosylation in human diabetic lens crystallins. Diabetologia. 1986 Apr;29(4):225–228. doi: 10.1007/BF00454880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oimomi M., Maeda Y., Hata F., Kitamura Y., Matsumoto S., Baba S., Iga T., Yamamoto M. Glycation of cataractous lens in non-diabetic senile subjects and in diabetic patients. Exp Eye Res. 1988 Mar;46(3):415–420. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(88)80029-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PIRIE A., VANHEYNINGEN R. THE EFFECT OF DIABETES ON THE CONTENT OF SORBITOL, GLUCOSE, FRUCTOSE AND INOSITOL IN THE HUMAN LENS. Exp Eye Res. 1964 Jun;3:124–131. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(64)80027-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pande A., Garner W. H., Spector A. Glucosylation of human lens protein and cataractogenesis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1979 Aug 28;89(4):1260–1266. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(79)92144-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao G. N., Cotlier E. Free epsilon amino groups and 5-hydroxymethylfurfural contents in clear and cataractous human lenses. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1986 Jan;27(1):98–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab I. R., Dawson C. R., Hoshiwara I., Szuter C. F., Knowler W. C. Incidence of cataract extraction in Pima Indians. Diabetes as a risk factor. Arch Ophthalmol. 1985 Feb;103(2):208–212. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1985.01050020060020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer R. N., Rosenthal G. Comparison of cataract incidence in normal and glaucomatous population. Am J Ophthalmol. 1970 Mar;69(3):368–371. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(70)92266-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szmyd L., Jr, Schwartz B. Association of systemic hypertension and diabetes mellitus with cataract extraction. A case-control study. Ophthalmology. 1989 Aug;96(8):1248–1252. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(89)32759-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor H. R., Muñoz B. Risk factors for cataract. Br J Ophthalmol. 1989 Jul;73(7):579–580. doi: 10.1136/bjo.73.7.579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe J. K., Chylack L. T., Jr Glucose metabolism by human cataracts in culture. Exp Eye Res. 1986 Aug;43(2):243–249. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(86)80092-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Heyningen R., Harding J. J. A case-control study of cataract in Oxfordshire: some risk factors. Br J Ophthalmol. 1988 Nov;72(11):804–808. doi: 10.1136/bjo.72.11.804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]