Abstract

Background

Paliperidone extended-release (paliperidone ER) is an approved oral antipsychotic medication (dosing range 3–12 mg/day) for treatment of schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder in adults.

Methods

In this 3-arm, double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled, parallel-group study, paliperidone ER 1.5 mg was assessed to determine the lowest efficacious dose in patients (N = 201) with acute schizophrenia. Paliperidone ER 6 mg was included for assay sensitivity.

Results

Patients (intent-to-treat analysis set) had a mean age of 39.4 years; 74% were men, 43% Asian, and 40% black. The baseline mean (SD) Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) total score was 92.6 (13.02) and the mean (SD) change from baseline to endpoint was: placebo group, –11.4 (20.81); paliperidone ER 1.5 mg group, –8.9 (23.31); and paliperidone ER 6 mg group, –15.7 (26.25). Differences between paliperidone groups versus placebo were not significant (paliperidone ER 1.5 mg [p = 0.582], paliperidone ER 6 mg, [p = 0.308]). Safety results of paliperidone ER 1.5 mg and placebo were comparable. The most frequently reported treatment emergent adverse events (≥10%) were: placebo group—headache (15.6%) and psychotic disorder (14.1%); paliperidone ER 1.5 mg group—insomnia (13.6%); and paliperidone ER 6 mg group—headache (11.4%), insomnia (10%), and tremor (10%).

Conclusions

In this study, paliperidone ER 1.5 mg did not demonstrate efficacy in patients with acute schizophrenia. A markedly high placebo response was noted. Assay sensitivity with the 6 mg dose was not established. Paliperidone ER 1.5 mg was generally tolerable with a safety profile comparable to placebo.

Keywords: Antipsychotic, extended-release, lowest effective dose, paliperidone, schizophrenia

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a chronic condition requiring consistent, long-term treatment. As for all long-term treatment strategies, a balance of optimal efficacy and minimal risk of adverse events must be considered for the patient.1

Paliperidone extended-release (ER) is an atypical once-daily antipsychotic, approved in the United States (US), the European Union, and many other countries for the treatment of schizophrenia in adults. In addition, in the US it is approved for schizoaffective disorder in adults.2 The recommended dose range for paliperidone ER is 3 to 12 mg once daily, which was established in short-term studies of paliperidone ER for the treatment of schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder.3-7 The current 6-week, phase 4, double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled, parallel-group study was designed to evaluate the efficacy, safety, and pharmacokinetics of a low dose of paliperidone ER (1.5 mg/day) compared with placebo in adult patients with schizophrenia to determine the lowest effective dose and potentially mitigate the risk of certain dose-related adverse effects.

Materials and Methods

Patients

Consenting men and women (≥18 years) with an established diagnosis of schizophrenia (as per the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition [DSM-IV]) for at least one year before screening, having an acute exacerbation of the disease, with a documented Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) total score between 70 and 120 (at screening and baseline), and who had agreed to voluntary hospitalization for a minimum of 8 days were enrolled.

Main exclusion criteria included: primary DSM-IV Axis I diagnosis other than schizophrenia, DSM-IV diagnosis of active substance dependence within 6 months before screening, history of neuroleptic malignant syndrome, circumstances that could increase the risk of the occurrence of torsade de pointes or sudden death, or any medical condition that could potentially alter the absorption, metabolism, or excretion of the study drug (e.g., Crohn’s, liver, or renal disease). Other exclusion criteria were: a significant risk of suicidal, homicidal, or violent ideation or behavior, use of the disallowed medications or hypersensitivity or intolerance to risperidone or paliperidone, injection of a depot antipsychotic within 120 days before screening, or use of paliperidone palmitate within 10 months before screening, and women who were pregnant, nursing, or planning to become pregnant.

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles that have their origin in the Declaration of Helsinki and that are consistent with Good Clinical Practices and applicable regulatory requirements. All patients provided written informed consent before entering the study.

Study Medication

Paliperidone ER 1.5 mg and paliperidone ER 6 mg were provided as capsule-shaped longitudinal compressed tablets consisting of two drug layers and a push layer with a Push-Pull™ delivery system (proprietary OROS® pump technology), designed to deliver 1.5 mg and 6 mg of paliperidone, respectively. The patients took once-daily dose of identically appearing overencapsulated paliperidone ER tablets (1.5 mg, or 6 mg), or matching overencapsulated placebo tablets.

Study Design, Randomization, and Blinding

This was a randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled, fixed-dose study conducted from September 2007 through November 2008 at 22 sites across 3 countries: United States, India, and Taiwan.

This study consisted of a screening period of up to 5 days for washout of disallowed medications, followed by a 6-week double-blind treatment period, and a follow-up visit 7 days later. Eligible patients were randomly assigned (1:1:1) to receive fixed oral doses of paliperidone ER (1.5 mg or 6 mg,) or placebo, based on a computer-generated randomization schedule and stratified by study center. Hospitalization was required for at least the first 8 days of study drug administration. The dose was administered daily in the morning for a 6 week period (days 1 to 42). As the paliperidone ER 6 mg dose has already been approved based on the same primary end point, this dose was included in this study to compare with placebo for the purpose of establishing assay sensitivity.

Concomitant Medications

Antiparkinsonian medications (benztropine, biperiden), beta-adrenergic blockers only to treat treatment-emergent akathisia and hypertension, antidepressants (except for nonselective or irreversible monoamine oxidase inhibitors) if they had been used at a stable dose for at least 3 months before screening, and oral benzodiazepines at the permitted maximum daily doses, were allowed.

Study Assessments

Efficacy Assessments

The primary efficacy endpoint was the change in the PANSS total score from baseline to the end of the double-blind treatment period (day 43 or last postbaseline assessment). The secondary efficacy endpoints included the change from baseline to the end of double-blind treatment period in Personal and Social Performance (PSP) Scale, in Clinical Global Impression-Severity (CGI-S) score and Medical Outcomes Study Short Form Health Survey-36 (MOS SF-36).8 A trained clinician administered these scales at the scheduled visits and the same person administered the scales at all visits.

Safety Assessments

Safety assessments included recording and monitoring of treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs), clinical laboratory tests, vital sign measurements, physical examination findings, 12-lead electrocardiograms, and extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) rating scales—Simpson and Angus Rating Scale (SAS);9 Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale (BARS);10 and Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS).11

Pharmacokinetic Assessments

Blood samples were collected for pharmacokinetic (PK) analysis on day –1 (blank for study drug), and day 8 (1–2 hours predose, 1–3 hours postdose, and 6 hours postdose). The plasma concentrations of paliperidone were determined using a validated liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry LC-MS/MS method, at Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development, N.V., Beerse, Belgium.

Analysis Sets

All the efficacy analyses were performed on the intent-to-treat (ITT) analysis set, which included all randomized patients who received at least 1 dose of double-blind study medication and provided both the baseline and at least 1 postbaseline efficacy assessment (PANSS, PSP, or CGI-S, MOS SF-36) during the double-blind phase. The safety analysis set included all patients who were randomized and received at least one dose of double-blind study medication. The all-randomized analysis set (including all randomly assigned patients regardless of whether or not treatment was received) provided the completion and withdrawal information. The per-protocol analysis set excluded ITT patients with major protocol violations. Pharmacokinetic analysis was performed as planned. No population PK analysis was performed.

Statistical Evaluations

The primary efficacy variable was analyzed using an ANCOVA model, with treatment and country as factors, and baseline PANSS total score as a covariate. The least-squares means (LSM) were estimated and compared between the placebo and paliperidone ER 1.5 mg treatment groups. A 2-sided 95% confidence interval (CI) was presented for the difference of the LSMs between paliperidone ER 1.5 mg group and the placebo group. Although not preplanned, this information was also provided for paliperidone ER 6 mg vs. the placebo groups, so as to assess assay sensitivity of the study. Hence, no multiplicity adjustment was made for treatment comparisons. Summary statistics (N, mean, SD, median, and range) for the primary efficacy variable were reported for all 3 treatment groups. For the secondary variables (CGI-S, PSP, MOS SF-36), an ANCOVA model similar to that for the primary variable was applied to the change from baseline values, for both last observation carried forward (LOCF) and observed case data, at each time point of evaluation and at endpoint. The covariate was the associated baseline score. For CGI-S, the ANCOVA was based on the ranked changes (and unranked baseline score).

Sample Size Determination

A sample size of 65 patients per treatment group provided 87.5% power to detect a treatment difference of at least 11 points between paliperidone ER 1.5 mg and placebo in the change from baseline to the 6-week endpoint in PANSS total score. A standard deviation of 20 points in the change from baseline in PANSS total score was assumed. With an estimate of approximately 3% of randomly assigned patients who would discontinue before providing either a baseline or postbaseline PANSS total score measurements, the number of randomly assigned patients was 67 in each treatment group, with a total sample size of 201 patients for 3 treatment groups. The above power and sample size calculations were based on a 2-sided hypothesis with a 5% level of significance.

Safety results were summarized using descriptive statistics.

Pharmacokinetics Analyses

Descriptive statistics were calculated for the plasma concentrations of paliperidone obtained on day –1 and day 8 (1 to 2 hours predose, 1 to 3 hours postdose, and 6 hours postdose). No formal statistical comparison of PK results between dose groups was performed. For the 136 patients who were randomly assigned to paliperidone ER (1.5 mg group: 66 patients, 6 mg group: 70 patients), a total of 490 scheduled PK blood samples were taken. Of these 490 samples, 483 samples were analyzed for paliperidone plasma concentrations; 481 samples of which were included in the PK analysis (2 samples were excluded due to missing dosing information). PK data were analyzed only for all patients in the paliperidone treatment groups with available plasma concentrations. Placebo samples were available but were not analyzed.

Results

Patient Characteristics and Disposition

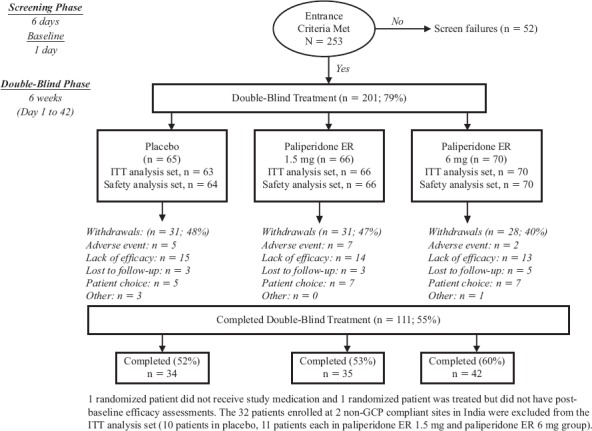

In total, 201 patients were randomly assigned to 1 of 3 treatment groups and 111 (55%) of the randomly assigned patients completed the study, with a completion rate of 53% to 60% in the paliperidone ER groups (Figure 1). The safety analysis set included 200 patients, the ITT analysis set included 167 patients, and the per protocol analysis set included 147 patients. Following an internal systems audit conducted by the sponsor, Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development, two sites in India were found to not have been Good Clinical Practice compliant. Thus, the 32 patients enrolled at these investigational sites were excluded from the intent-to-treat analysis set and the per protocol analysis set in the subsequent analyses.

Figure 1.

Patient Accounting

The most common reasons for premature discontinuation from the study were: lack of efficacy (21%), patient choice (9%), and adverse event (7%) (Figure 1). Psychiatric disorders were the most common adverse events leading to discontinuation. The percentage of patients who discontinued due to lack of efficacy was slightly higher in the placebo (23%) and paliperidone ER 1.5 mg groups (21%) than the paliperidone ER 6 mg group (19%).

Demographics and baseline characteristics were comparable among groups with the exception that the paliperidone ER 6 mg had a relatively lower percentage of black patients 16 (27%) compared to placebo 27 (51%) and paliperidone ER 1.5 mg groups 24 (44%) (Table 1). Patients (ITT analysis set) had a mean (SD) age of 39.4 (11.68) years, 74% were men, and majority of the patients were Asian (43%) or black (40%). Prior atypical antipsychotic use (69%) was more common than typical antipsychotic drug use (19%); risperidone was the most commonly used atypical antipsychotic in the 3 treatment groups (20% to 31% patients). Prior anti-EPS medications were administered to 22% of patients. The mean (SD) PANSS total score at baseline was 92.6 (13.02). The median duration of exposure was similar among the three treatment groups (41 days for placebo and paliperidone ER 1.5 mg groups, 42 days for paliperidone ER 6.0 mg group).

Table 1. Demographics and Baseline Characteristics (Intent-to-Treat Analysis Set).

| PLACEBO (N = 53) | PALIPERIDONE ER 1.5 mg (N = 55) | PALIPERIDONE ER 6 mg (N = 59) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Men | 39 (74) | 43 (78) | 41 (69) |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| White | 6 (11) | 8 (15) | 11 (19) |

| Black | 27 (51) | 24 (44) | 16 (27) |

| Asian | 20 (38) | 22 (40) | 30 (51) |

| Other1 | 0 | 1 (2) | 2 (3) |

| Age (Years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 36.4 (10.72) | 41.1 (11.58) | 40.7 (12.24) |

| Weight (kg) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 79.2 (26.29) | 77.8 (24.83) | 73.1 (22.02) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 27.3 (9.41) | 26.7 (8.22) | 26.2 (7.19) |

| Age at diagnosis of schizophrenia (yrs) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 24.5 (7.39) | 24.7 (8.57) | 25.4 (9.59) |

| Schizophrenia type, n (%) | |||

| Disorganized | 0 | 1 (2) | 1 (2) |

| Paranoid | 44 (83) | 46 (84) | 52 (88) |

| Undifferentiated | 9 (17) | 8 (15) | 6 (10) |

| Prior antipsychotic use, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 44 (83) | 46 (84) | 53 (90) |

| No | 9 (17) | 9 (16) | 6 (10) |

| Baseline CGI-S, n (%) | |||

| Mild | 1 (2) | 0 | 1 (2) |

| Moderate | 22 (42) | 26 (47) | 30 (51) |

| Marked | 23 (43) | 25 (45) | 24 (41) |

| Severe | 7 (13) | 4 (7) | 3 (5) |

| Extremely severe | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) |

Other: American Indian/Alaskan Native (1 in each paliperidone ER group); Not specified for 1 patient (paliperidone ER 6 mg group).

For placebo, N = 52, for age at diagnosis of schizophrenia.

Efficacy Findings

Primary Efficacy Parameter

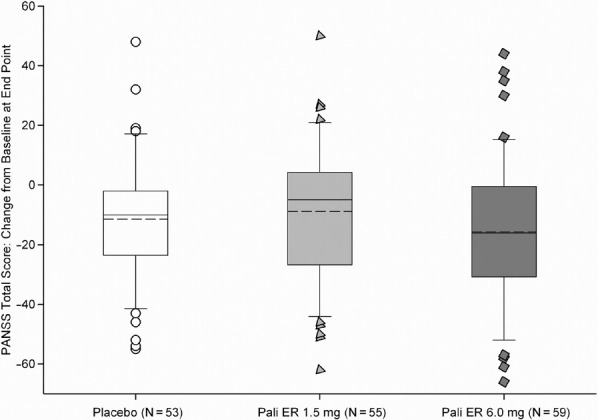

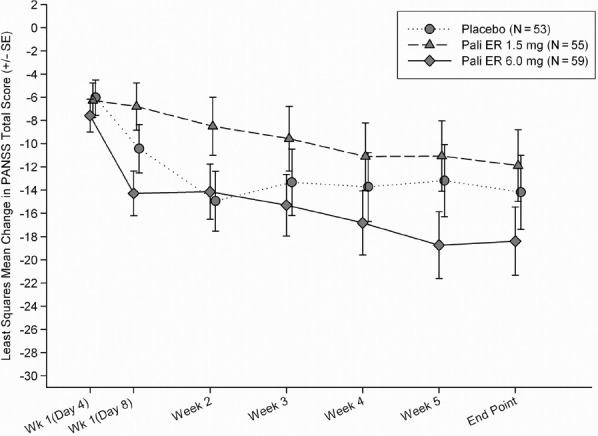

Although the mean improvement at endpoint in the PANSS total score for the placebo group was higher than in the paliperidone ER 1.5 mg group, the difference between groups was not significant (p = 0.582) (Figure 2A). The LSM difference [95% CI] from placebo was 2.3 (–5.95, 10.55) (Figure 2B). The LSM difference (95% CI) of paliperidone ER 6 mg from placebo for the change in PANSS total score was –4.2 (–12.34, 3.92). In the per protocol analysis set, the greatest improvement from baseline was seen in the paliperidone ER 6 mg group, followed by placebo and paliperidone ER 1.5 mg groups. The differences between placebo and each paliperidone dose group were not significant in these per protocol analysis and were consistent with the results observed in the ITT population. To further assess the sensitivity of the results, longitudinal analysis of PANSS total score was performed with treatment, time, country, and a treatment-by-time interaction term as factors and baseline PANSS total score as a covariate. This analysis revealed a significant time effect (p < 0.0001), significant treatment-by-time interaction effect (p = 0.007) and a non-significant treatment effect (p = 0.398) indicating that the change from baseline in PANSS total score depended on time, and that the difference between treatments varied over time. Placebo showed a greater decrease from baseline compared to paliperidone ER 1.5 mg at all time points except at week 4 and week 6. Paliperidone ER 6 mg group showed the greatest mean improvement compared to placebo and the paliperidone ER 1.5 mg group at all time points except at week 2, where the highest mean improvement was observed in the placebo group. There was a significant treatment by country interaction (p = 0.049). In addition, a significant treatment-by-region interaction was observed when the 3 countries were categorized into India and non-India (p = 0.021). Further exploration of the treatment-by-region interaction using the 2-sided Gail-Simon test indicated that the interaction is quantitative (i.e., there is a variation in magnitude, but not direction, of the treatment effect in the 2 regions) for either of the 2 paliperidone ER doses (paliperidone ER 1.5 mg versus placebo: p = 0.166; paliperidone ER 6 mg versus placebo: p = 0.324). Because the paliperidone ER 6 mg did not show a significant improvement compared with placebo, assay sensitivity was not established.

Figure 2A.

Change from Baseline to Endpoint in the PANSS Total Score (LOCF) (Intent-to-Treat Analysis Set)

Figure 2B.

Least-Squares Mean Change from Baseline in the PANSS Total score Over Time (LOCF) (Intent-to-Treat Analysis Set)

Secondary Efficacy Parameters

There was no statistical difference between paliperidone ER 1.5 mg and placebo for the change from baseline to endpoint in the CGI-S score (p = 0.653), the PSP score (p = 0.957), and the MOS SF-36 physical and mental component summary scores (p = 0.237 and p = 0.448, respectively) (Table 2).

Table 2. Change from Baseline to Endpoint (LOCF) in Secondary Outcome Measures (Intent-to-Treat Analysis Set).

| EFFICACY MEASURE | PLACEBO | PALIPERIDONE ER 1.5 mg | PALIPERIDONE ER 6 mg |

|---|---|---|---|

| CGI-S, Median (Range) | |||

| n | 53 | 55 | 59 |

| Baseline | 5.0 (3; 6) | 5.0 (4; 6) | 4.0 (3; 7) |

| Change from baselinea | −1.0 (−2; 1) | 0.0 (−3; 2) | 0.0 (−3; 1) |

| p-value (minus placebo) | 0.653 | ||

| PSP Score, Mean (SD) | |||

| n | 49 | 47 | 56 |

| Baseline | 49.9 (13.71) | 47.3 (12.68) | 47.9 (14.05) |

| Change from baselineb | 2.0 (15.58) | 2.7 (12.14) | 5.1 (12.43) |

| p-value (minus placebo) | 0.957 | ||

| MOS SF-36, Mean (SD) | |||

| n | 50 | 49 | 56 |

| Physical component summary scale | |||

| Baseline | 51.5 (7.98) | 48.3 (8.94) | 49.4 (6.93) |

| Change from baselineb | 0.2 (7.27) | 0.1 (9.37) | 0.8 (9.93) |

| p-value (minus placebo) | 0.237 | ||

| Mental component summary scale | |||

| Baseline | 40.3 (12.01) | 42.3 (13.42) | 37.7 (9.61) |

| Change from baselineb | 3.9 (13.86) | 1.0 (11.98) | 6.2 (14.06) |

| p-value (minus placebo) | 0.448 |

PSP−Personal and Social Performance Scale; and CGI-S−Clinical Global Impression-Severity;

MOS SF-36−Medical Outcomes Study Short Form Health Survey-36.

Negative change in score indicates improvement.

Positive change in score indicates improvement.

Safety and Tolerability Findings

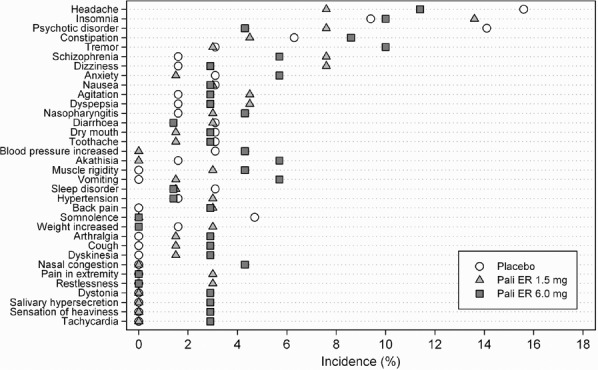

Overall, TEAEs occurred at similar rates among the paliperidone ER 1.5 mg (64%) and paliperidone ER 6 mg groups (69%) and the placebo group (73%). The most commonly reported TEAEs (≥10%) were headache (15.6%) and psychotic disorder (14.1%) in the placebo group, insomnia (13.6%) in the paliperidone ER 1.5 mg group, and headache (11.4%), insomnia (10%), and tremor (10%) in the paliperidone ER 6 mg group. The TEAEs noted more frequently in the paliperidone ER 1.5 mg group than the placebo group (≥5% difference) were schizophrenia and dizziness (7.6% vs 1.6% for both events) (Figure 3). The incidences of akathisia (5.7%) and tremor (10%) were reported more commonly in the paliperidone ER 6 mg dose group than in either the placebo (akathisia: 2%; tremor: 3%) or paliperidone ER 1.5 mg (akathisia: none; tremor: 3%) groups.

Figure 3.

Treatment-Emergent Adverse Events Experienced by at Least 2% of Patients in Any Treatment Group (Safety Analysis Set)

No patients died during the study. The incidence of serious adverse events (SAE) was higher in the placebo (10.9%) and paliperidone ER 1.5 mg groups (10.6%) compared with that in the paliperidone ER 6 mg group (7.1%); all the SAEs were psychiatric disorders. The incidence of TEAEs leading to a permanent discontinuation of study medication was lower in the paliperidone ER 6 mg (2.9%) group than in the placebo group (7.8%) and the paliperidone ER 1.5 mg group (10.6%). This imbalance was mainly attributable to psychotic disorder, the most common TEAE leading to discontinuation in the placebo (6.3%) and paliperidone ER 1.5 mg (6.1%) treatment groups.

There was a low incidence of TEAEs related to abnormal ECG findings (1 patient each in the placebo and paliperidone ER 6 mg groups. Tachycardia was reported only in the paliperidone ER 6 mg group (2 patients). One of the events resolved and the other was reported as persisting. No action was taken with study drug for the tachycardia in either patient. No patient was discontinued for a cardiac-related AE. A maximum increase from baseline of >60 ms in QTcLD (QTc interval calculated using the linear-derived formula) was observed for 1 patient (paliperidone ER 6 mg group) (average predose: 371 ms; maximum post baseline: 468 ms; change from baseline of 97 ms).

The incidence of EPS-related TEAEs was higher in the paliperidone ER 6 mg group compared with those in the placebo and paliperidone ER 1.5 mg groups. Tardive dyskinesia, dystonia, oculogyric crisis, and trismus events occurred only in the paliperidone ER 6 mg group. At endpoint, the median changes for SAS and AIMS scores were 0 in all treatment groups and majority of patients in each treatment group (range 85.3%–98.4%) scored 0 (absent) in the global clinical rating score for akathisia from the BARS. The use of anti-EPS medication during the double-blind period was reduced from baseline usage in the placebo (8% vs 17%) and paliperidone ER 1.5 mg (15% vs 23%) groups but remained similar (21% vs 21%) for the paliperidone ER 6 mg group. Only one patient (placebo group) was noted with glucose metabolism-related TEAE (increased blood glucose level). There were no TEAEs associated with hyperprolactinemia reported during the study.

The changes in fasting glucose levels from normal to high (<100 mg/dL to ≥126 mg/dL) were observed in 2 (4.5%) patients in the placebo group, 2 (5.4%) in the paliperidone ER 1.5 mg group and 3 (7.0%) in the paliperidone ER 6 mg group (Table 3).

Table 3. Change from Baseline to Endpoint in Different Laboratory Parameters (Safety Analysis Set).

| PLACEBO (N = 64) | PALIPERIDONE ER 1.5 mg (N = 66) | PALIPERIDONE ER 6 mg (N = 70) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose (mmol/L), Mean (SD) | |||

| n | 56 | 55 | 60 |

| Change from baseline | −0.0 (1.21) | 0.1 (0.98) | 0.1 (3.81) |

| Glucose | |||

| n | 44 | 37 | 43 |

| Change from normal to higha | |||

| (<100 mg/dL to ≥126 mg/dL), n (%) | 2 (4.5%) | 2 (5.4%) | 3 (7.0%) |

| Prolactin, (ng/ml), Mean (SD) | |||

| n | 54 | 52 | 60 |

| Change from baseline | −0.1 (10.89) | 18.6 (37.47) | 51.4 (65.60) |

| Prolactin, (ng/ml) in men, Mean (SD) | |||

| n | 40 | 39 | 38 |

| Change from baseline | −1.1 (9.28) | 6.9 (15.04) | 22.9 (21.15) |

| Prolactin, (ng/ml) in women, Mean (SD) | |||

| n | 14 | 13 | 22 |

| Change from baseline | 3.0 (14.54) | 53.6 (59.03) | 100.6 (85.43) |

| Weight (Kg), Mean (SD) | |||

| n | 56 | 58 | 64 |

| Change from baseline | 0.6 (3.09) | 2.7 (18.27) | 0.5 (2.75) |

| Weight Decrease ≥ 7%, n (%) | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | 4 (6) |

| Weight Increase ≥ 7%, n (%) | 3 (5) | 4 (7) | 2 (3) |

change from baseline to the maximum post-baseline value.

Mean weight increased from baseline to endpoint by 0.7% in the placebo and paliperidone ER 6 mg groups and 2.5% in the paliperidone ER 1.5 mg group. The higher mean percent weight increase in the 1.5 mg group is likely a data error in one patient whose recorded weight increase is reported as 138 kg from baseline. There were no clinically relevant changes from baseline in clinical laboratory parameters in any of the treatment groups.

Pharmacokinetic Findings

The mean plasma concentrations of paliperidone were dose proportional (Table 4).

Table 4. Actual Plasma Concentrations of Paliperidone ER:Descriptive Statistics.

| ACTUAL PLASMA CONCENTRATION (ng/mL) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | MEAN | (SD) | %CV | MEDIAN | |||||||

| Paliperidone ER 1.5 mg | |||||||||||

| Day −1 | Predose | 64 | BQL | (−) | - | BQL | |||||

| Day 8 | Predose | 56 | 5.08 | 3.65 | 71.8 | 4.48 | |||||

| 1-3 hr postdose | 54 | 4.95 | 3.51 | 71 | 4.53 | ||||||

| 6 hr postdose | 54 | 4.87 | 3.53 | 72.5 | 4.47 | ||||||

| Paliperidone ER 6 mg | |||||||||||

| Day −1 | Predose | 68 | BQL | (−) | - | BQL | |||||

| Day 8 | Predose | 61 | 27.4 | 19.3 | 70.3 | 21.6 | |||||

| 1-3 hr postdose | 62 | 26.3 | 19.5 | 74.1 | 20 | ||||||

| 6 hr postdose | 62 | 24.3 | 16.6 | 68.4 | 19 | ||||||

BQL−below quantifiable limit.

Discussion

Efficacy of the low dose of paliperidone ER 1.5 mg was not demonstrated in this placebo- and active-controlled study in schizophrenia. Overall, the placebo response observed in the primary efficacy measurement was notably greater than that observed in any of the previous paliperidone ER studies. Although paliperidone ER 6 mg showed a numerically larger improvement compared with placebo, the difference was not significant. The per-protocol analysis results were consistent with those observed for the ITT population in the primary analysis. Hence, assay sensitivity was not established. However, the mean improvement from baseline in PANSS total score in the paliperidone ER 6 mg group in this phase 4 study (–15.7) was similar to that from the pivotal phase 3 studies (–15.7 and –17.9) that established efficacy at this dose.3-5,12 An imbalance in race was noted in this study, with a higher percentage of black patients (51%) and lower percentage of white patients (11%) in placebo compared with paliperidone ER 1.5 mg group (black [44%]; white [15%]) and paliperidone ER 6 mg group (black [27%]; white [19%]). While there is a suggestion in the literature of greater percentage reduction in PANSS scores in black patients13 as well as a lower placebo response in white patients14 with psychotropic medication, a race bias has not been consistently demonstrated in placebo controlled trials investigating the treatment of schizophrenia.15 The absence of assay sensitivity in this study may in part be due to the markedly greater mean improvement in the placebo group and the slightly larger variability of the changes in PANSS total score in the paliperidone ER 6.0 mg group observed in this study versus the pooled data in these groups from previous studies.3-5 However, even if the placebo group had shown similar change from baseline as in the earlier pooled studies (mean [SD] –4.8 [21.95])16 the 1.5 mg group would still not have differed statistically from placebo. In addition, the safety profile (adverse events and reasons for discontinuation) of the 1.5 mg dose closely resembles that of placebo, suggesting comparable potency. Thus, although this study did not conclusively establish the lowest effective dose, it would appear that 1.5 mg/day is not an efficacious dose.

The mean paliperidone plasma concentrations were consistent with historical data.3-5,12 The small difference in mean paliperidone concentrations between the predose and the postdose timepoint reflect the low peak-to-trough variation. The mean dose-normalized plasma paliperidone concentrations were comparable between the treatment groups, confirming the dose-proportional pharmacokinetics in the dose range of 1.5 and 6 mg.17

The highest incidence of TEAEs overall was in the placebo group (73%) compared with the paliperidone ER 1.5 mg (64%) and the 6 mg (69%) groups. However, the proportion of serious TEAEs and the TEAEs leading to discontinuations was greater in the placebo and the paliperidone ER 1.5 mg groups; mainly attributable to the psychotic disorders (>2 patients) in these two groups. The safety profile of paliperidone ER 1.5 mg and placebo was comparable. Overall, paliperidone ER at the doses evaluated was generally tolerable in the treatment of schizophrenia and no new safety signals were detected. No patients died during the study. The incidence of movement disorder-related TEAEs in the paliperidone ER 1.5 mg group were similar to placebo (≤2 patients for each EPS-related TEAE) and slightly higher in the 6 mg group (≤7 patients for each EPS-related TEAE). In line with the EPS-related TEAEs, no changes were noted in the EPS scores. Kinon et al., reported that fewer detectable TEAEs can lead to increased placebo response as it is more difficult for the patient to guess his/her treatment assignment.18 Similarly in our study we observed lower incidence of TEAEs in the paliperidone ER 6 mg group and a higher response in the placebo and paliperidone ER 1.5 mg arms. Also the percentage of patients who withdrew from the study due to lack of efficacy was slightly higher in placebo group (23%) versus paliperidone ER 1.5 mg (21%) and paliperidone ER 6 mg groups (19%). The safety results are consistent with those of previous 6 week, placebo-controlled studies,3-5,12 and a pooled analysis of 52-week studies for paliperidone ER in schizophrenia.19

The cardiometabolic events associated with the second generation antipsychotics have generated substantial concerns.20 However, there were no reports of glucose-related TEAEs observed in this study. The higher mean percent weight increase of 2.5% in the 1.5 mg group is likely a data error in one patient whose recorded weight increase is reported as 138 kg from baseline. Lipid levels were not measured in this study. No treatment-emergent abnormal QT intervals were noted for any patient during the study, except for one occurrence of QTcLD change from baseline of 97 ms in a woman in the paliperidone ER 6 mg group. Overall, the low incidences of cardiometabolic events such as weight gain or glucose-related TEAEs support a favorable benefit-risk profile for paliperidone ER.

Conclusions

The current study, designed to determine the minimum effective dose of paliperidone ER, did not demonstrate efficacy of paliperidone ER 1.5 mg in adult patients with acute schizophrenia. A markedly high placebo response was noted comparable with earlier studies of paliperidone ER (3–15 mg)3-5,12 and assay sensitivity using the 6 mg dose could not be established. Paliperidone ER was generally tolerable in this study.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Madhavi Patil (SIRO Clinpharm Pvt. Ltd.) provided writing assistance and Dr. Wendy P. Battisti (Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development, L.L.C.) provided additional editorial support for this manuscript.

The authors thank the study participants, without whom this study would not have been accomplished, as well as the following investigators for their participation in this study:

India: Jhanwar, Venu Gopal, M.B.B.S., M.D.; Chandra Sekhar, Kammammettu M.D., D.P.M.; Parkhi, Sandeep, M.B.B.S., M.D.; Ramakrishna, Podaralla, M.B.B.S., M.D.; Taiwan: Cheng, Jror-Serk, M.D.; Lan, Tsuo-Hung, Ph.D.; Lin, Chaucer, Ph.D.; Ouyang Wen-Chen, M.D., Ph.D.; Wang, Chen-Pang, M.D.; United States of America: Borenstein, Jeffrey, M.D.; Brenner, Ronald, M.D.; Cutler, Andrew J., M.D.; Garcia, Donald J., M.D.; Knapp, Richard D., D.O.; Litman, Robert E., M.D.; Lowy, Adam F., M.D.; Marandi, Morteza, M.D.; Noori, Darius, M.D.; Riesenberg, Robert A., M.D.; Walling, David, P., Ph.D.

Footnotes

Registration

This study is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT00524043)

Study Support

Funded by Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development, L.L.C., Raritan, N.J., USA. The sponsor also provided a formal review of this manuscript.

Author Contributions

All authors met International Council of Medical Journal Editors criteria and all those who fulfilled those criteria are listed as authors. All authors had access to the study data, provided direction and comments on the manuscript, made the final decision about where to publish these data, and approved submission to the journal. Specifically, Drs. Coppola, Singh, Nuamah, Gopal, Hough, Palumbo and Ms. Melkote and Lannie contributed to study design, data interpretation, and analysis. Ms. Melkote, Dr. Nuamah and Ms. Lannie oversaw the statistical analyses and provided interpretation of the data. Dr Patil (see acknowledgments) developed the first draft with the direction from all authors and editorial assistance was provided by Dr. Battisti.

Disclosures

Drs. Coppola, Singh, Nuamah, Gopal, Hough, Palumbo and Ms. Melkote are employees of Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development L.L.C. Ms. Lannie is an employee of Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development, Division of Janssen Pharmaceutica NV, Beerse, Belgium.

References

- 1.Lublin H, Eberhard J, Levander S. Current therapy issues and unmet clinical needs in the treatment of schizophrenia: a review of the new generation antipsychotics. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005;20(4):183–198. doi: 10.1097/00004850-200507000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Invega® Prescribing Information. last update July 2009. Available at http://www.janssen.com/janssen/shared/pi/invega Accessed on 18 Jan, 2010.

- 3.Davidson M, Emsley R, Kramer M, Ford L, Pan G, Lim P et al. Efficacy, safety and early response of paliperidone extended-release tablets (paliperidone ER): results of a 6-week, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Schizophr Res. 2007;93(1-3):117–130. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kane JM, Canas F, Kramer M, Ford L, Gassmann-Mayer C, Lim P et al. Treatment of schizophrenia with paliperidone extended-release tablets: a 6-week placebo-controlled trial. Schizophr Res. 2007;90(1-3):147–161. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marder SR, Kramer M, Ford L, Eerdekens E, Lim P, Eerdekens M et al. Efficacy and safety of paliperidone extended-release tablets: results of a 6-week, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62(12):1363–1370. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Canuso C, Lindenmayer JP, Carothers J. Randomized,double-blind placebo-controlled study of two dose ranges of paliperidone ER in the treatment of subjects with schizoaffective disorder. 64th Annual Convention and Scientific Program of the Society of Biological Psychiatry (SOBP), Vancouver, Canada Biological Psychiatry. 2009:213–4S. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Canuso C, Schooler N, Kosik-Gonzalez C. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of flexible-dose paliperidone ER in the treatment of patients with schizoaffective disorder. 64th Annual Convention and Scientific Program of the Society of Biological Psychiatry (SOBP), Vancouver, Canada. Biological Psychiatry. 2009:213S. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Russo J, Trujillo CA, Wingerson D, Decker K, Ries R, Wetzler H et al. The MOS 36-Item Short Form Health Survey: reliability, validity, and preliminary findings in schizophrenic outpatients. Med Care. 1998;36(5):752–756. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199805000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simpson G, Angus J. A rating scale for extrapyramidal side effects. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1970;212:11–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1970.tb02066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barnes TR. A rating scale for drug-induced akathisia. Br J Psychiatry. 1989;154:672–676. doi: 10.1192/bjp.154.5.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guy W. Vol. 338. Rockville, MD: National Institute of Mental Health; 1976. AIMS Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale, Early Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit (ECDEU), Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology, Rev Ed; pp. 534–537. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kramer M, Simpson G, Maciulis V et al. Paliperidone extended-release tablets for prevention of symptom recurrence in patients with schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;27(1):6–14. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e31802dda4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Emsley RA, Roberts MC, Rataemane S et al. Ethnicity and treatment response in schizophrenia: a comparison of 3 ethnic groups. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:9–14. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v63n0103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen D, Consoli A, Bodeau N et al. Predictors of placebo response in randomized controlled trials of psychotropic drugs for children and adolescents with internalizing disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2010;20(1):39–47. doi: 10.1089/cap.2009.0047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lawson WB, Herman BK, Loebel A et al. Ziprasidone in black patients with schizophrenia: analysis of four short-term, double-blind studies. CNS Spectr. 2009 Sep;14(9):478–486. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900023543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meltzer HY, Bobo WV, Nuamah IF et al. Efficacy and tolerability of oral paliperidone extended-release tablets in the treatment of acute schizophrenia: pooled data from three 6-week, placebo-controlled studies. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(5):817–829. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boom S, Talluri K, Janssens L et al. Single- and multiple-dose pharmacokinetics and dose proportionality of the psychotropic agent paliperidone extended release. J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;49(11):1318–1330. doi: 10.1177/0091270009339190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kinon BJ, Potts AJ, Watson SB. Placebo response in clinical trials with schizophrenia patients. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2011;24:107–113. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32834381b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Emsley R, Berwaerts J, Eerdekens M et al. Efficacy and safety of oral paliperidone extended-release tablets in the treatment of acute schizophrenia: pooled data from three 52-week open-label studies. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(6):343–356. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0b013e328314e1f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.American Diabetes Association. Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs and obesity and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(2):596–601. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.2.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]