Abstract

Objectives

To pilot efficacy and safety data of quetiapine-XR monotherapy or adjunctive therapy to antidepressant(s) in the acute treatment of MDD with current generalized anxiety disorder (GAD).

Methods

The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview was used to ascertain the diagnosis of DSM-IV Axis I disorders. Eligible patients were randomly assigned to quetiapine-XR or placebo for up to 8 weeks. Changes from baseline to endpoint in Hamilton Depression Rating Scale-17 items (HAMD-17), Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A), Clinical Global Impression-Severity (CGI-S), Quick Inventory of Depression Symptomatology-16 items Self-Report (QIDS-16-SR) total scores, and other outcome measures were analyzed with the last observation carried forward strategy and/or mixed-effects modeling for repeated measures.

Results

Of the 34 patients screened, 23 patients were randomized to receive quetiapine-XR (n = 11) or placebo (n = 12), with 5 and 4 completing the study, respectively. The mean dose of quetiapine-XR was 154 ± 91 mg/d. The change from baseline to endpoint in the total scores of HAMD-17, HAM-A, QIDS-16-SR, and CGI-S were significant in the quetiapine-XR group, but only the change in HAM-A total score was significant in the placebo group. The differences in these changes between the two groups were only significant in CGI-S scores, with the rest of numerical larger in the quetiapine-XR group. The most common side effects from quetiapine-XR were dry mouth, somnolence/sedation, and fatigue.

Conclusions

In this pilot study, quetiapine-XR was numerically superior to placebo in reducing depressive and anxiety symptoms in patients with MDD and current GAD. Large sample studies are warranted to support or refute these preliminary findings.

Keywords: major depressive disorder, comorbid generalized anxiety disorder, randomized placebo-controlled trial, quetiapine-XR

Introduction

Comorbidity in major depression disorder (MDD) is the rule rather than the exception, with comorbid generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) appearing to be among the most prevalent.1–4 Comorbidity anxiety affects the course of MDD2 with more symptomatic distress and more severe and recurrent episodes.2,5 Patients with MDD and comorbid anxiety disorder(s) commonly have poorer psychosocial functioning, more suicidal behaviors,6,7 longer chronic courses,8 and alcohol use disorders.9–12

Meanwhile, a growing body of literature demonstrates that patients with MDD and comorbid anxiety commonly receive inadequate-treatments.13 However, there is no guideline or consensus on pharmacological treatment for comorbid anxiety disorders (ADs) like GAD in MDD. Moreover, pharmacological and psychological treatments were recommended previously based on the data from patients with relatively “pure” MDD.14 More importantly, there is no efficacy data to support the best selection of antidepressants in MDD accompanying anxiety. Benzodiazepines, a second-line medication for some ADs, can be used in the treatment of anxiety in MDD, but may be riskier to prescribe for those with anxiety and substance use disorder.15 Undoubtedly, long-term treatment with a benzodiazepine in patients with MDD and GAD may increase not only the total healthcare costs but also the risk for abuse or dependence.16

Previous studies have shown that patients with MDD with comorbid anxiety symptoms were less likely to respond traditional antidepressant treatments.17–20 In a post-hoc analysis of the efficacy and tolerability of once-daily venlafaxine-XR (75–225 mg/d), and fluoxetine (20–60 mg/d) versus placebo in patients with MDD and concomitant anxiety, Silverstone and Salinas reported that venlafaxine-XR, but not fluoxetine, was superior to placebo in depressive symptoms in a subset of patients with MDD and GAD. In contrast, both medications were superior to placebo in non-comorbid depressed patients.21 Moreover, the onsets of efficacy to response were also slower with both medications in comorbid patients than in non-comorbid patients.

Aforementioned evidence suggests that data from “pure” populations of patients with MDD or GAD may not be generalizable to a comorbid population of patients with MDD. Studies of quetiapine-XR in bipolar depression have also shown that quetiapine-XR was less effective in patients with bipolar depression and comorbid GAD and/or panic disorder than in those with relatively “pure” bipolar depression.22–24

Previous studies have shown that typical and atypical antipsychotics were superior to placebo and as effective as benzodiazepines in the treatment of primary GAD.25–27 Quetiapine-XR (extended release) monotherapy was superior to placebo in the treatment of patients with “pure” GAD28,29 or “pure” MDD.30,31 More recently, post-hoc analyses of those pivotal studies have shown that quetiapine-XR was superior to placebo in reducing anxiety symptoms in patients with MDD,30 agitation and sleep disturbances in mood disorders.32 It remains unclear if quetiapine-XR has similar efficacy and safety in patients with MDD and current GAD. This study was undertaken to pilot the safety and efficacy data of quetiapine-XR versus placebo in a cohort of patients with MDD and current GAD.

Methods

The study was conducted in the Mood and Anxiety Clinic within the Mood Disorders Program at Case Western Reserve University/University Hospitals Case Medical Center, Cleveland, Ohio from February, 2008 to August, 2011. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) at University Hospital Case Medical Center approved all study procedures. Written informed consent was obtained from each subject before any study-related procedures were performed.

Study Design

This study was a randomized, double-blind, 8-week comparison of quetiapine-XR monotherapy or adjunctive therapy to antidepressant(s) versus placebo monotherapy or adjunctive therapy to antidepressant(s) in the acute treatment of MDD comorbid with current GAD. All patients who discontinued the study due to any reason received 3 monthly routine clinical care gratis visits.

Study Subjects

Males and females from 18 to 65 years old who met DSM-IV criteria for major depression disorder, currently depressed with Hamilton Depression Rating Scale-17 items (HAMD-17) total score ≥ 18 at screening and baseline visits, and a current history of GAD with a Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A) total score ≥ 18 at screening and baseline visits were eligible. In addition, patients were required to be in good physical health. Patients were excluded if they had: 1) Severe medical or neurological problems; 2) Severe personality disorder; 3) Current suicidal risk judged by a physician; 4) Known history of intolerance or hypersensitivity to any of the medications involved in the study; 5) Treatment with quetiapine ≥ 100 mg/day in the 6 months prior to randomization; 6) Known lack of response to quetiapine in a dosage of ≥ 100 mg/day for 4 weeks at any time, as judged by the investigator; 7) DSM-IV criteria for substance use disorder confirmed by the Substance Use Disorder Module of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID), for any substance except for caffeine and nicotine, with substance abuse within last 30 days or substance dependence within last 90 days; 8) Concurrent obsessive-compulsive disorder; 9) Use of any cytochrome P450 3A4 inhibitors or cytochrome P450 inducers in 14 days; 10) Unable to wean off benzodiazepines or other unpermitted medication; 12) Female patients who were pregnant, planning to be pregnant or breastfeeding.

Prescreening and Screening Phase

An Extensive Clinical Interview was performed to confirm the diagnosis of MDD and GAD to determine if the inclusion and exclusion criteria were met.33 During the screening visit, all Axis I disorders were ascertained with the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) performed by a Master’s-level prepared research assistant.

Eligible subjects were randomized within 28 days after the screening visit. With the exception of antidepressants including selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and selective serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SSNIs), all other medications were discontinued at least 5 half-lives prior to randomization. The permitted medication(s) was maintained at a stable dose for a minimal 2 week period.

Randomization and Double-Blind Treatment Phase

Random assignment to each arm was balanced for gender, male versus female. The study medications were started at 50 mg for day 1 and day 2, increased to 150 mg at day 3 and day 4, and finally increased to 300 mg/d at day 5 and onward. For those who could not tolerate 300 mg/d, a 50 mg decrement per week was allowed to a minimum of 150 mg/d. For those who could not tolerate 150 mg/d, they were discontinued from the study. Assessments were performed week 0, 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8.

Concomitant Medications

Rescue medication for sleep such as Zopidem (Ambien 5–10 mg/d or Ambien-CR 6.25–12.5 mg/d) was permitted during the washout period and the double-blinded phase. Except for the aforementioned antidepressant(s), no other medication was allowed.

Primary and Secondary Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was the change from baseline to the end of study (EOS) in HAMD-17 total scores. Secondary outcome measures included: mean changes from baseline to EOS in total scores of the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A), Clinical Global Impression-Severity (CGI-S), Quick Inventory of Depression Symptomatology— 16 item self-report (QIDS-16-SR),34 the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (Q-LES-Q),35 and the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS). For those with panic disorder and/or social phobia, the Panic Disorder Severity Scale (PDSS),36 and Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS) were used to measure the severity of panic or social anxiety symptoms. Secondary outcomes also included the response rate (≥50% reduction in HAMD-17 or HAM-A total score from baseline to endpoint) and remission rate (HAMD-17 total score or HAM-A total score < 7 at endpoint).

Safety Monitoring

Safety was monitored by assessing adverse events (AEs), including extrapyramidal symptoms (Parkinsonism) as measured with the Simpson Angus Scale (SAS),37 akathisia as measured with the Barnes Akathisia Scale (BARS),38 the Frequency, Intensity, and Burden of Side Effects Rating scale (FIBSER).39 In addition, clinical laboratory assessments and physical exam performed at baseline were repeated at the endpoint.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics, percentage, mean and standard deviation were obtained for the patients’ demographic and baseline clinical characteristics. The primary and secondary efficacy analyses were performed on the intent-to-treat (ITT) population, i.e., all randomized patients who received at least 1 dose of study medication and had at least 1 post-baseline assessment. Treatment effects were tested using a two-tailed α-level of 0.05. Data were analyzed using SAS software (SAS version 9.2, SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

As specified a priori of the primary outcome measure, the change in HAMD-17 total scores over the 8-week treatment period was performed using the last observation carry forward (LOCF) strategy and a mixed-effects model of repeated measures (MMRM). A first-order autoregressive, variance-covariance structure was assumed in the MMRM model.

The effect size was calculated by the net changes in the HAMD-17 or HAMA total scores of quetiapine-XR from baseline to the endpoint over placebo divided by pooled standard deviation. The significance of the change from baseline to endpoint in HAMD-17 or other rating scale total score within the group or between groups was examined with ANOVA or ANCOVA. Chi-Square or Fisher’s exact test (n < 5) was used to analyze categorical data of treatment differences, and baseline demographic and illness characteristics.

Results

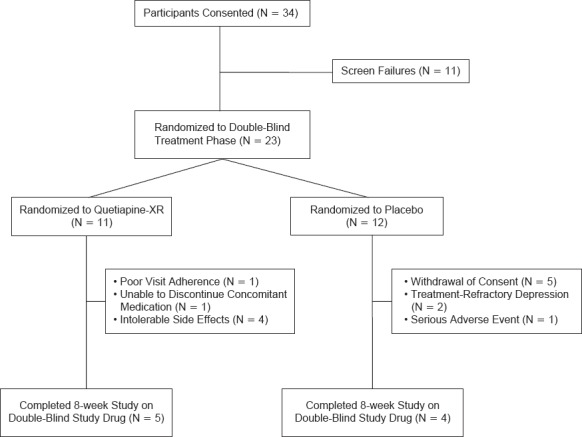

There were 34 patients screened, 23 were randomized, and 9 patients completed the 8-week study with 5 in quetiapine-XR group and 4 in placebo group, respectively (Figure 1). The most common reason for discontinuation was intolerable side effects in quetiapine-XR group and withdrawal of consent in placebo group (Figure 1). The mean dose of quetiapine-XR was 154 ± 91 mg/d (50–300 mg/d). In the 23 randomized patients, 9 were on adjunctive therapy (4 in quetiapine-XR group and 5 in placebo group) and 14 were on monotherapy (7 each in quetiapine-XR group and placebo group). There were no significant differences between two groups in the number of patients who received monotherapy or adjunctive therapy.

Figure 1.

Study Flow Chart of Patient Recruitment

Baseline Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

As shown in Table 1, there were no significant differences between quetiapine-XR and placebo groups in age, gender, marital status, and education level, but a significant number of African-American patients were randomized to placebo than to quetiapine-XR. There were no significant differences between the two treatment arms in the age at first depressive episode, the total number of mood episodes, the number of hospitalizations, and the number of previous suicide attempts. The proportion of patients with a history of comorbid anxiety disorders, substance use disorders, eating disorder, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder was similar. The rates of early childhood trauma and previous psychotropic medication use were also similar.

Table 1. Baseline Demographics and Historical Correlates.

| VARIABLES | QUETIAPINE-XR (N = 11) | PLACEBO (N = 12) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGE | MEAN | SD | MEAN | SD |

| 48.7 | 8.92 | 52.7 | 14.81 | |

| N | % | N | % | |

| Male | 3 | 27.27 | 3 | 25.00 |

| Female | 8 | 72.73 | 9 | 75.00 |

| Black or African-American | 8 | 72.73 | 3 | 25.00 |

| White or Caucasian | 3 | 27.27 | 9 | 75.00 |

| Single | 8 | 81.82 | 4 | 33.33 |

| Married | 1 | 9.09 | 3 | 25.00 |

| Completed High School | 3 | 27.27 | 5 | 41.67 |

| Completed College or higher | 4 | 36.36 | 2 | 16.67 |

| History of Social Phobia | 6 | 54.55 | 3 | 27.27 |

| History of Panic Disorder | 5 | 45.45 | 5 | 45.45 |

| History of PTSD | 0 | 0.00 | 2 | 18.18 |

| History of OCD | 1 | 9.09 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Agoraphobia without panic | 2 | 18.18 | 6 | 54.55 |

| Specific phobia | 1 | 9.09 | 0 | 0.00 |

| History of alcohol use disorder | 2 | 16.67 | 5 | 41.67 |

| History of drug use disorder | 3 | 27.27 | 6 | 50.00 |

| History of ADHD | 1 | 9.09 | 1 | 9.09 |

| Eating Disorder | 2 | 18.18 | 0 | 0 |

| History of Verbal Abuse | 5 | 45.45 | 3 | 27.27 |

| History of Physical Abuse | 3 | 27.27 | 4 | 36.36 |

| History of Sexual Abuse | 1 | 9.09 | 1 | 9.09 |

| Previous antidepressant treatment | 3 | 11.54 | 5 | 9.52 |

| Previous antipsychotic use | 0 | 0.00 | 3 | 5.77 |

| Previous benzodiazepine | 2 | 7.69 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Previous stimulants | 1 | 3.85 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Other Psych medications | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 1.92 |

Abbreviations: ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; N, number of patients; OCD, obsessive compulsive disorder; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; SD, standard deviation; XR, extended release.

Primary Outcome

After the 8-week treatment, the HAMD-17 total scores decreased significantly in the quetiapine-XR group, from 22.64 ± 4.01 at baseline to 14.18 ± 8.17 at the endpoint (p = 0.0078). In contrast, the change from baseline to endpoint of HAMD-17 total scores in the placebo group was not significant, from 24.73 ± 4.36 at baseline to 19.36 ± 8.55 at the endpoint (p = 0.837). The difference in the change from baseline and endpoint in HAMD-17 between the two groups was not significant (LOCF) either with AVONA or ANCOVA, 8.45 ± 8.58 for the quetiapine-XR and 5.36 ± 8.77 for the placebo group, respectively. MMRM analysis also found no significance between two groups (Table 2). The Cohen’s d effect size of the difference in HAMD-17 total score between quetiapine-XR and placebo was 0.43.

Table 2. Changes from Baseline to Endpoint in Primary and Secondary Outcome Measures (MMRM).

| QUETIAPINE-XR (N = 11) | PLACEBO (N = 11) | QUETIAPINE-XR VS. PLACEBO | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BASELINE | ENDPOINT | BASELINE | ENDPOINT | DIFFERENCE IN CHANGES | |||||||||||

| VARIABLES | MEAN | SD | MEAN | SD | MEAN | SD | MEAN | SD | LS MEAN | P | |||||

| HAMD-17 | 22.6 | 4.0 | 14.2 | 8.2 | 24.6 | 4.2 | 19.7 | 8.2 | 3.5 | 0.333 | |||||

| HAMA | 25.5 | 4.6 | 14.2 | 9.5 | 26.1 | 5.9 | 17.8 | 8.7 | 2.9 | 0.406 | |||||

| CGI-S | 4.5 | 0.7 | 3.4 | 1.0 | 4.3 | 0.5 | 4.1 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.036 | |||||

| QIDS-16-SR | 15.0 | 6.2 | 9.3 | 5.5 | 14.3 | 4.2 | 12.2 | 7.3 | 3.7 | 0.214 | |||||

| Q-LES-Q | 21.6 | 5.9 | 26.4 | 13.4 | 21.6 | 7.0 | 25.1 | 9.2 | 21.3 | 0.830 | |||||

| SDS | 15.3 | 8.5 | 13.8 | 11.5 | 21.0 | 4.7 | 19.2 | 6.3 | 0.1 | 0.971 | |||||

| YMRS | 6.1 | 2.8 | 6.3 | 6.3 | 4.9 | 1.6 | 5.1 | 3.4 | 20.02 | 0.993 | |||||

| N | % | N | % | ||||||||||||

| HAMD response | 4 | 36.36 | 3 | 27.27 | n/a | 1.000 | |||||||||

| HAMA response | 6 | 54.55 | 4 | 36.36 | n/a | 0.3918 | |||||||||

| HAMD+HAMA response | 3 | 27.27 | 3 | 27.27 | n/a | 0.6699 | |||||||||

| HAMD remission | 2 | 18.18 | 0 | 0 | n/a | 0.4762 | |||||||||

| HAMA remission | 5 | 45.45 | 2 | 18.18 | n/a | 0.3615 | |||||||||

| HAMD+HAMA remission | 2 | 18.18 | 0 | 0 | n/a | 0.4762 | |||||||||

Notes: Response ≥ 50% improvement in HAMD-17 or HAMA total score; Remission defined as HAMD-17 total score or HAMA total score < 7 at endpoint of the study.

Abbreviations: CGI-S, Global Clinical Impression-Severity; HAMA, Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; HAMD-17, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale—17 items; N, number of patients; MMRM, Mixed-Effects Model of Repeated Measures; QIDS-16-SR, 16 item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology—Self Report; Q-LES-Q, Quality of Life, Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire; SD, standard deviation; SDS, Sheehan Disability Scale; XR, extended release; YMRS, Young Mania Rating Scale.

Secondary Outcomes

In the quetiapine-XR group, the changes form baseline to endpoint in HAM-A, CGI-S, and QIDS-16 total scores were also significant, from 25.45 ± 4.61 to 14.18 ± 17.73 (p = 0.0031), from 4.55 ± 0.69 to 3.36 ± 1.03 (p = 0.0048), and from 15.00 ± 6.21 to 9.73 ± 5.44 (p = 0.047), respectively. In the placebo group, only the change in HAM-A score from baseline to endpoint was significantly different, from 26.82 ± 5.56 to 17.73 ± 9.08 (p = 0.0103). In between-group comparisons, only the change from baseline to endpoint in CGI-S was significantly larger in the quetiapine-XR group compared to that in the placebo group (Table 2). The Cohen’s d effect size of the difference in HAM-A total scores between quetiapine-XR and placebo was 0.32.

There were no significant differences in changes from baseline to endpoint in YMRS, Q-LES-Q, SDS, PDSS and LSAS in either group or magnitudes of changes in these variables from baseline to endpoint between the two groups.

Response rates based on ≥ 50% reduction in HAMD-17 and/or HAM-A total scores were not significantly different between two groups although the quetiapine-XR group had numerical higher rates of response than the placebo group, 36.36% versus 27.27% for depression response and 54.55% versus 36.36% for anxiety response (Table 2). Similarly, the rates of remission based on HAMD-17 and/or HAM-A , 7 were also not significantly different between the two group although, again, the quetiapine-XR group had numerical higher rates of remission than the placebo group, 18.18% versus 0% for depression remission and 45.45% versus 18.18% for anxiety remission. There were also no significant differences in responder rates between those who were on monotherapy and those who were on adjunctive therapy within the treatment group.

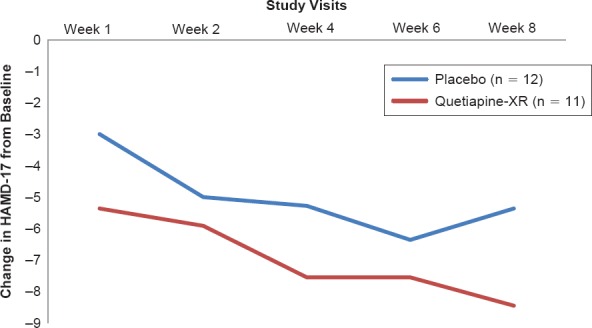

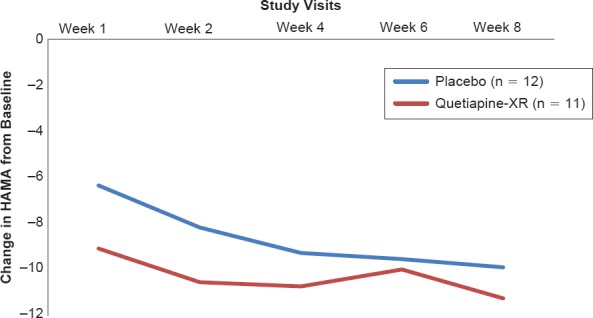

Visit Changes in HAMD-17 and HAM-A

As shown in Figure 2A, the treatment-by-time interaction indicated a greater reduction in the HAMD-17 total score in the quetiapine-XR group than in the placebo group, but there were no significant differences between two groups in changes in HAMD-17 total score at each visit. Similarly, the treatment-by-time interaction showed a greater reduction in HAM-A total score in the quetiapine-XR group than in the placebo group, but there were no significant differences between two groups in changes in HAM-A total score at each visit (Figure 2B).

Figure 2A.

Changes from Baseline at Scheduled Visits in Hamilton Depression Rating Scale—17 item Total Scores

Adverse Events

Adverse events experienced by total patients during the double-blind treatment phase are summarized in Table 3. The rate of dry mouth was significantly higher in the quetiapine group than that in the placebo, 54.55% versus 8.33% (p = 0.0549). The rate of fatigue was trended higher in the quetiapine group than that in the placebo 45.45% versus 16.67% (p = 0.0612). The rate of reported sedation/somnolence was significantly higher in the quetiapine group than that in the placebo 36.36% versus 0% (p = 0.0372). Four patients in quetiapine-XR group and one patient in placebo group discontinued the study due to intolerable adverse events (p = 0.1176). The laboratory results including fasting glucose, fasting lipids, and thyroid function and vital signs were also not significantly different.

Table 3. Adverse Events During Study Period.

| QUETIAPINE-XR | PLACEBO | |

|---|---|---|

| Total Incidences of side effects | 30 | 16 |

| Dry mouth | 6 | 1 |

| Fatigue | 5 | 2 |

| Somnolence/sedation | 4 | 0 |

| Other GI side effects | 3 | 2 |

| Headaches | 3 | 0 |

| Other neurological side effects | 2 | 3 |

| Dizziness | 1 | 2 |

| Anxiety | 1 | 0 |

| Jitteriness | 1 | 0 |

| Blurred vision | 1 | 0 |

| Crying | 1 | 0 |

| Insomnia | 0 | 3 |

| Increased appetite | 0 | 1 |

| Irritability | 1 | 0 |

| Rage | 1 | 0 |

| Suicide attempt | 0 | 1 |

Abbreviation: XR, extended release.

Discussion

The findings from this pilot study are consistent with most previous studies in relatively “pure” populations of patients with major depressive disorder30,31,40–42 or generalize anxiety disorder,28,29 in which quetiapine-XR were significantly superior to placebo in reducing depressive and anxiety symptoms. Although the difference in changes from baseline to endpoint in CGI-S score between quetiapine-XR and placebo was the only variable significantly different between the two groups, the changes in HAMD-17, HAM-A, and QIDS-16-SR scores showed a similar trend, suggesting that quetiapine-XR was more effective than placebo in reducing depressive and anxiety symptoms in this comorbid group of patients (Table 2).

The difference in changes of HAMD-17 total score was 3.6 points which are larger than those of previous studies in “pure” MDD patients. A Meta-analysis of previous studies of quetiapine-XR in “pure’ MDD found that the mean difference in changes from baseline to endpoint between quetiapine-XR 50–300 mg/d monotherapy and placebo was 2.46 points.41 However, the difference between placebo and a fixed dose of quetiapine-XR 150 mg/d monotherapy or adjunctive therapy to antidepressant was from 2.68 to 3.43 points.43–45 A flexible dose study showed that quetiapine-XR 150–300 mg/d monotherapy resulted in 3.39 point difference between the active treatment and placebo.46

In contrast, the difference (9.1%) in response rates between quetiapine-XR and placebo in the present study was lower than those of previous studies based on ≥ 50% improvement in MADRS scores, ranging from 11.5% difference to 20.9% difference between quetiapine-XR and placebo.43–46 These data suggest that the antidepressant efficacy of quetiapine-XR in patients with MDD and comorbid current GAD may not be as effective as that in patients with relatively “pure” MDD.

The mean difference in the reduction of anxiety symptom (a HAM-A total score of 2.9 points) between quetiapine-XR and placebo in the present study was also consistent with previous studies in patients with “pure” GAD,47–49 in which the difference in the reduction of HAM-A total score between quetiapine-XR 50–300 mg/d and placebo ranged from 0.77 to 3.6 points.26 A fixed dose of quetiapine-XR 150 mg/d produced large differences from 2.44 to 3.66 points.26 The 0.32 Cohen’s D effect size in the present study is exactly the same as that of quetiapine-XR 150 mg/d in patients with MDD and baseline HAM-A total score < 26 points.30 Anxiety symptoms in relatively “pure” MDD patients were also significantly reduced with quetiapine-XR compared to placebo.44,45 The difference in changes between quetiapine-XR and placebo was from 1.78 points to 2.35 points. These data suggest that quetiapine-XR in patients with MDD and GAD may be as effective as in patients with “pure” GAD in reducing anxiety symptoms.

The speed of action for reducing depressive symptoms of quetiapine-XR relative to placebo in the present study is also consistent with previous studies of quetiapine-XR in “pure” MDD patients (Figure 2). At the end of week 1, the difference in HAMD-17 total score reduction was 2.36 points which were similar to the 2.2 to 2.7 point difference at the end of week 1 of two previous studies in patients with “pure” MDD.45 Post-hoc analyses of previous quetiapine-XR studies in “pure” MDD did not find significant differences in response to quetiapine-XR treatment relative to placebo between those with low anxiety symptoms and those with high anxiety symptoms.50,51

These findings appear to be contradictory to previous studies with traditional antidepressants,17–21 i.e., patients with anxious depression or MDD and GAD are less likely to respond to treatments and more likely to take a longer time to respond. This discrepancy may be due to the key difference in sedative/hypnotic effect between traditional antidepressants and quetiapine-XR, suggesting that patients with MDD and GAD or high anxiety level may benefit more from quetiapine-XR than from traditional antidepressants.

In terms of safety and tolerability, the present study showed similar findings as previous quetiapine-XR studies in MDD or GAD as dry mouth and somnolence/sedation as the most common side effects.52,53 Previously, we have shown that patients with MDD or GAD had similar sensitivity to quetiapine-XR related to side effect, but patients with GAD did not tolerate to quetiapine-XR as well as those with MDD as reflected with a smaller number needed to treat for the discontinuation due to adverse event relative to placebo.53 It remains unclear if patients with MDD and GAD have similar tolerability as those with MDD or those with GAD although there were 4 patients in quetiapine-XR group discontinued the study due to intolerable side effects and none in the placebo group.

Limitations

Although this was the first double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial in patients with MDD and current GAD without a recent SUD, OCD, or PTSD, this study was limited by enrolling a small number of patients. Using GAD as an index comorbid anxiety disorder may limit the generalizability of this study to patients with other comorbid anxiety disorder(s) although large number of patients with social phobia, panic disorder and/or agoraphobia (Table 1). It is further limited by even lower numbers of patients completing the study.

Conclusion

In this study of comorbid patients with MDD and GAD, quetiapine-XR reduced depressive and anxiety symptoms more than placebo in patients with MDD and GAD with an estimated Cohen d effect size of 0.43 and 0.32, respectively. Quetiapine-XR was less tolerable than placebo. Large studies are warranted to support or refute these preliminary findings. More importantly, there is an urgent need to conduct randomized, controlled studies in MDD with comorbid anxiety disorder(s) and with or without a substance use disorder to identify effective treatments for highly comorbid populations.

Figure 2B.

Changes from Baseline at Scheduled Visits in Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale Total Scores

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by AstraZeneca Pharmaceutical Company via an Investigator Initiated study.

References

- 1.Gili M, García Toro M, Armengol S et al. Functional impairment in patients with major depressive disorder and comorbid anxiety disorder. Can J Psychiatry. 2013;58(12):679–686. doi: 10.1177/070674371305801205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mergl R, Seidscheck I, Allgaier AK et al. Depressive, anxiety, and somatoform disorders in primary care: prevalence and recognition. Depress Anxiety. 2007;24(3):185–195. doi: 10.1002/da.20192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) JAMA. 2003;289(23):3095–3105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gao K, Wang Z, Chen J et al. Should an assessment of Axis I comorbidity be included in the initial diagnostic assessment of mood disorders? Role of QIDS-16-SR total score in predicting number of Axis I comorbidity. J Affect Disord. 2013;148(2-3):256–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cyranowski JM, Schott LL, Kravitz HM et al. Psychosocial features associated with lifetime comorbidity of major depression and anxiety disorders among a community sample of mid-life women: the SWAN mental health study. Depress Anxiety. 2012;29(12):1050–1057. doi: 10.1002/da.21990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pfeiffer PN, Ganoczy D, Ilgen M et al. Comorbid anxiety as a suicide risk factor among depressed veterans. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26(8):752–757. doi: 10.1002/da.20583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gao K, Ming R, Wang Z et al. Differential associations of the number of comorbid conditions and the severity of depression and anxiety with self-reported suicidal ideation and attempt in major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder. J Depression Anxiety. 2015;4(1):173. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mittal D, Fortney JC, Pyne JM et al. Predictors of persistence of comorbid generalized anxiety disorder among veterans with major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(11):1445–1451. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10m05981blu. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bet PM, Hugtenburg JG, Penninx BW et al. Treatment inadequacy in primary and specialized care patients with depressive and/or anxiety disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2013;210(2):594–600. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boschloo L, Vogelzangs N, van den Brink W et al. Depressive and anxiety disorders predicting first incidence of alcohol use disorders: results of the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA) J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(12):1233–1240. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12m08159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Angst J. Depression and anxiety: implications for nosology, course, and treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58(Suppl. 8):3–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reich J, Warshaw M, Peterson LG et al. Comorbidity of panic and major depressive disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 1993;27(Suppl. 1):23–33. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(93)90015-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Economic Working Group Advisory Board. Undertreatment of depression and comorbid anxiety translates into costly mismanagement of resources and poor patient outcomes. Manag Care. 2005;14(7 Suppl.):1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anderson IM, Ferrier IN, Baldwin RC et al. Evidence-based guidelines for treating depressive disorders with antidepressants: a revision of the 2000 British Association for Psychopharmacology guidelines. J Psychopharmacol. 2008;22(4):343–396. doi: 10.1177/0269881107088441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brunette MF, Noordsy DL, Xie H et al. Benzodiazepine use and abuse among patients with severe mental illness and co-occurring substance use disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54(10):1395–1401. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.10.1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berger A, Edelsberg J, Treglia M et al. Change in healthcare utilization and costs following initiation of benzodiazepine therapy for long-term treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:177. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Souery D, Oswald P, Massat I et al. Clinical factors associated with treatment resistance in major depressive disorder: results from a European multicenter study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(7):1062–1070. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu Z, Chen J, Yuan C et al. Difference in remission in a Chinese population with anxious versus nonanxious treatment-resistant depression: a report of OPERATION study. J Affect Disord. 2013;150(3):834–839. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee TS, Nkouibert Assam P, Gersing KR et al. The effectiveness of antidepressant monotherapy in a naturalistic outpatient setting. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2012;14(5) doi: 10.4088/PCC.12m01364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shelton RC, Hollon SD, Wisniewski SR et al. Factors associated with concomitant psychotropic drug use in the treatment of major depression: a STAR*D Report. CNS Spectr. 2009;14(9):487–498. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900023555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Silverstone PH, Salinas E. Efficacy of venlafaxine extended release in patients with major depressive disorder and comorbid generalized anxiety disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(7):523–529. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v62n07a04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suppes T, Datto C, Minkwitz M et al. Effectiveness of the extended release formulation of quetiapine as monotherapy for the treatment of acute bipolar depression. J Affect Disord. 2010;121(1-2):106–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sheehan DV, Harnett-Sheehan K, Hidalgo RB et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of quetiapine XR and divalproex ER monotherapies in the treatment of the anxious bipolar patient. J Affect Disord. 2013;145(1):83–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gao K, Wu R, Kemp DE et al. Efficacy and safety of quetiapine-XR as monotherapy or adjunctive therapy to a mood stabilizer in acute bipolar depression with generalized anxiety disorder and other comorbidities: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(10):1062–1068. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13m08847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gao K, Muzina D, Gajwani P et al. Efficacy of typical and atypical antipsychotics for primary and comorbid anxiety symptoms or disorders: a review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(9):1327–1340. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gao K, Sheehan DV, Calabrese JR. Atypical antipsychotics in primary generalized anxiety disorder or comorbid with mood disorders. Expert Rev Neurother. 2009;9(8):1147–1158. doi: 10.1586/ern.09.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Katzman MA. Current considerations in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. CNS Drugs. 2009;23(2):103–120. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200923020-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sheehan DV, Svedsäter H, Locklear JC et al. Effects of extended-release quetiapine fumarate on long-term functioning and sleep quality in patients with Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD): data from a randomized-withdrawal, placebo-controlled maintenance study. J Affect Disord. 2013;151(3):906–913. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Endicott J, Svedsäter H, Locklear JC. Effects of once-daily extended release quetiapine fumarate on patient-reported outcomes in patients with generalized anxiety disorder. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2012;8:301–311. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S32320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Montgomery SA, Altamura AC, Katila H et al. Efficacy of extended release quetiapine fumarate monotherapy in elderly patients with major depressive disorder: secondary analyses in subgroups of patients according to baseline anxiety, sleep disturbance, and pain levels. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;29(2):93–105. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0000000000000007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Katila H, Mezhebovsky I, Mulroy A et al. Randomized, double-blind study of the efficacy and tolerability of extended release quetiapine fumarate (quetiapine XR) monotherapy in elderly patients with major depressive disorder. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(8):769–784. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baune BT. New developments in the management of major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder: role of quetiapine. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2008;24(6):1181–1191. doi: 10.2147/ndt.s3238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gao K, Verduin ML, Kemp DE et al. Clinical correlates of patients with rapid-cycling bipolar disorder and a recent history of substance use disorder: a subtype comparison from baseline data of 2 randomized, placebo-controlled trials. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(7):1057–1063. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Ibrahim HM et al. The 16-Item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS), clinician rating (QIDS-C), and self-report (QIDS-SR): a psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54(5):573–583. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01866-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Endicott J, Nee J, Harrison W et al. Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire: a new measure. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1993;29(2):321–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shear MK, Rucci P, Williams J et al. Reliability and validity of the Panic Disorder Severity Scale: replication and extension. J Psychiatr Res. 2001;35(5):293–296. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(01)00028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simpson GM, Angus JW. A rating scale for extrapyramidal side effects. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1970;((Suppl. 212)):11–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1970.tb02066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barnes TR. A rating scale for drug-induced akathisia. Br J Psychiatry. 1989;154:672–676. doi: 10.1192/bjp.154.5.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wisniewski SR, Rush AJ, Balasubramani GK et al. Self-rated global measure of the frequency, intensity, and burden of side effects. J Psychiatr Pract. 2006;12(2):71–79. doi: 10.1097/00131746-200603000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weisler R, McIntyre RS. The role of extended-release quetiapine fumarate monotherapy in the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. Expert Rev Neurother. 2013;13(11):1161–1182. doi: 10.1586/14737175.2013.846520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maneeton N, Maneeton B, Srisurapanont M et al. Quetiapine monotherapy in acute phase for major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trials. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:160. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang G, McIntyre A, Earley WR et al. A randomized, double-blind study of the efficacy and tolerability of extended-release quetiapine fumarate (quetiapine XR) monotherapy in patients with major depressive disorder. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2014;10:201–216. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S50248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weisler R, Joyce M, McGill L et al. Extended release quetiapine fumarate monotherapy for major depressive disorder: results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. CNS Spectr. 2009;14(6):299–313. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900020307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cutler AJ, Montgomery SA, Feifel D et al. Extended release quetiapine fumarate monotherapy in major depressive disorder: a placebo- and duloxetine-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(4):526–539. doi: 10.4088/jcp.08m04592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bauer M, El-Khalili N, Datto C et al. A pooled analysis of two randomised, placebo-controlled studies of extended release quetiapine fumarate adjunctive to antidepressant therapy in patients with major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord. 2010;127(1-3):19–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bortnick B, El-Khalili N, Banov M et al. Efficacy and tolerability of extended release quetiapine fumarate (quetiapine XR) monotherapy in major depressive disorder: a placebo-controlled, randomized study. J Affect Disord. 2011;128(1-2):83–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bandelow B, Chouinard G, Bobes J et al. Extended-release quetiapine fumarate (quetiapine XR): a once-daily monotherapy effective in generalized anxiety disorder. Data from a randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled study. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2010;13(3):305–320. doi: 10.1017/S1461145709990423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Khan A, Joyce M, Atkinson S et al. A randomized, double-blind study of once-daily extended release quetiapine fumarate (quetiapine XR) monotherapy in patients with generalized anxiety disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(4):418–428. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e318224864d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Merideth C, Cutler AJ, She F et al. Efficacy and tolerability of extended release quetiapine fumarate monotherapy in the acute treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: a randomized, placebo controlled and active-controlled study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;27(1):40–54. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0b013e32834d9f49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thase ME, Demyttenaere K, Earley WR et al. Extended release quetiapine fumarate in major depressive disorder: analysis in patients with anxious depression. Depress Anxiety. 2012;29(7):574–586. doi: 10.1002/da.21970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bandelow B, Bauer M, Vieta E et al. Extended release quetiapine fumarate as adjunct to antidepressant therapy in patients with major depressive disorder: pooled analyses of data in patients with anxious depression versus low levels of anxiety at baseline. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2014;15(2):155–166. doi: 10.3109/15622975.2013.842654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gao K, Ganocy SJ, Gajwani P et al. A review of sensitivity and tolerability of antipsychotics in patients with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia: focus on somnolence. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(2):302–309. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gao K, Kemp DE, Fein E et al. Number needed to treat to harm for discontinuation due to adverse events in the treatment of bipolar depression, major depressive disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder with atypical antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(8):1063–1071. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09r05535gre. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]