Abstract

Purpose

Given the public’s trust and the opportunities to observe and address social determinants of health, physicians are well suited to be health advocates, a key role in the CanMEDS physician competency framework. As some physicians find it difficult to fulfill this role, the authors explored the experiences and influences that led established physicians to be health advocates.

Method

The authors used a phenomenological approach to explore this topic. From March to August 2014, they interviewed 15 established physician health advocates, using a broad definition of health advocacy—that it extends beyond individual patient advocacy to address the root causes of systemic differences in health. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. The transcripts were coded and the data categorized into clusters of meaning, then into themes. Data analysis was conducted iteratively, with data collection continuing until no new information was gathered.

Results

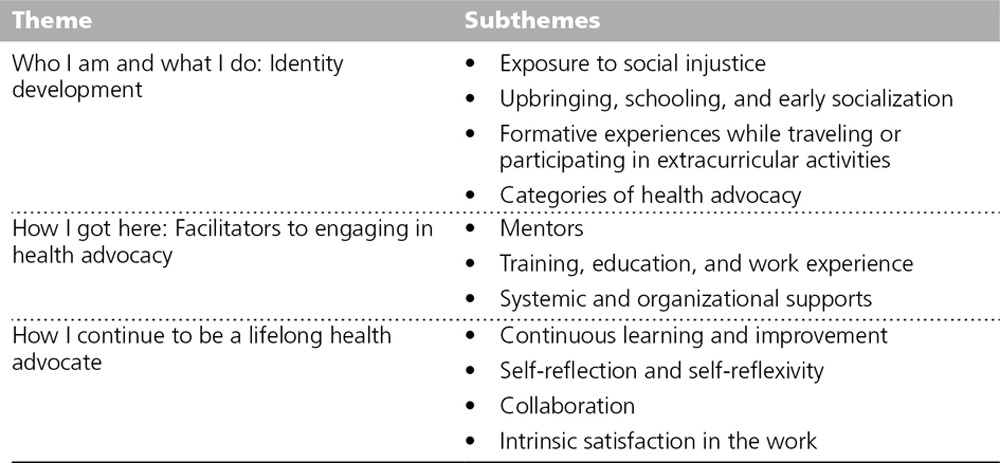

Participants described the factors that contributed to the development of their health advocate identity (i.e., exposure to social injustice, upbringing, schooling, specific formative experiences) and those that facilitated their engagement in health advocacy work (i.e., mentors, training, systemic and organizational supports). They also highlighted how they continue in their role as lifelong advocates (i.e., continuous learning and improvement, self-reflection and self-reflexivity, collaboration, intrinsic satisfaction in the work).

Conclusions

Many factors allow physician health advocates to establish and sustain a commitment to improve the health of their patients and the broader population. Medical schools could use these findings to guide curriculum development related to teaching this physician competency.

Repeatedly, physicians have been called to fulfill the role of health advocate for their patients.1–3 Health advocacy involves awareness and action that extends beyond the clinical presentations of individual patients to a concern for patient populations and the social determinants of health. Given the public’s trust in physicians and the opportunities available to them to observe and act to address the effects of social determinants, physicians are ideally suited for the role of health advocate.1

Competency frameworks and professionalism charters offer a more expansive definition of health advocacy and recognize physicians’ responsibility to fulfill this role. Health advocacy is one of the seven essential competencies in the CanMEDS physician competency framework from the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada (RCPSC).2,3 According to the RCPSC, in this role:

Physicians contribute their expertise and influence as they work with communities or patient populations to improve health. They work with those they serve to determine and understand needs, speak on behalf of others when required, and support the mobilization of resources to effect change.2

Similar definitions of health advocacy are included in the American Medical Association’s Declaration of Professional Responsibility4 and in the American Board of Internal Medicine’s charter on medical professionalism.5

Despite recognition of the importance of the health advocate role, a variety of barriers prevent physicians from assuming it, including time constraints, inadequate remuneration, absence of formal curriculum, lack of mentors, and the loss of empathy during medical training.6–8 Nevertheless, some physicians are passionately committed to health advocacy. Preliminary studies have indicated that early exposure to injustice, parental influence, role modeling, and internal motivators may be important factors affecting physicians’ pursuit of health advocacy work.6

Building on these findings, the primary objective of this study was to identify and explore pivotal experiences and influences that led physicians to be health advocates, according to a group of physicians with health advocacy experience. A secondary objective was to identify opportunities for the development of health advocacy curricula to train physicians to be more inclined, and better prepared, to engage in this important aspect of medical practice.

Method

We employed a phenomenological approach9,10 to explore the lived experiences of physician health advocates. We began by e-mailing physicians, who were nominated by our principal investigator (M.L.) because they were well known within the university community as health advocates whose work extended beyond individual patient advocacy. We then used snowball and maximum variation sampling to recruit additional participants from other disciplines across Canada. We also asked participants to recommend physician health advocates from different disciplines and locations. We sought participant diversity in geography (urban vs. rural), discipline, and number of years in practice.

From March to August 2014, a research assistant (P.V.) experienced in qualitative research conducted one-on-one, semistructured interviews in person or by phone. Eight family physicians and seven specialists (four internal medicine, two public health, one psychiatry) were interviewed; six (40%) were women. Years in practice ranged from 3 to 35, with an average of 17.5 years (median of 19 years). Participants provided written informed consent prior to being interviewed and were offered a small honorarium in the form of a gift card.

Using a semistructured interview guide (see List 1), we asked participants to share accounts of their experiences and to describe the factors that led them to become health advocates. In keeping with the expanded understanding of health advocacy, we asked participants to use the following operational definition while discussing their health advocate role:

List 1. Semistructured Interview Guide From a Study of the Experiences and Factors That Led 15 Physicians to Be Health Advocates, 2014.

-

Tell me a little bit about yourself.

Probes: Tell me about your practice, your field of medicine, length of time in practice, etc.

-

How would you define health advocacy?

Probes: What are the characteristics or qualities of a good/effective health advocate? What roles does a health advocate play?

-

We’re defining advocacy as: “Action by a physician to promote those social, economic, educational, and political changes that ameliorate the suffering and threats to human health and well-being that he or she identifies through his or her professional work and expertise.”1 This definition emphasizes a role beyond individual advocacy to address the root causes of systemic health problems. Please describe your own involvement in health advocacy.

Probes: Tell me the story of how you became a health advocate. How did you become involved in advocacy? When did you become involved? Has this role changed? Please provide examples of your health advocacy.

-

What specific factors led to you becoming a health advocate?

Probes: What contributed to this? What got you involved? Please describe your training in health advocacy (informal or formal)? What experiences during your medical training may have motivated you to participate in health advocacy? What mentors/role models have inspired your work in health advocacy?

What keeps you involved in health advocacy?

What do you think would be important to teach medical students in order to improve health advocacy competencies?

Other comments?

Action by a physician to promote those social, economic, educational, and political changes that ameliorate the suffering and threats to human health and well-being that he or she identifies through his or her professional work and expertise.1

We used probes to obtain further details during discussions (see List 1). Interviews ranged from 41 to 73 minutes and were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Data were deidentified by assigning transcripts a confidential study number. Immediately following each interview, the research assistant (P.V.) wrote field notes regarding observational or contextual details not captured by the audio recording. These notes informed the ongoing analysis and helped us formulate an understanding of the data.

Transcript data were entered into NVivo 10 (QSR International; Melbourne, Australia) for organization and coded line by line by the research assistant (P.V.). Data then were categorized into themes representing experiences and factors of interest. As the analysis proceeded, early codes (i.e., units of meaning) were refined and grouped into broader themes. For example, the code “exposure to suffering” evolved into “exposure to social injustice” and then was subsumed under the theme “Who I am and what I do: Identity development.” The code “establishment” became part of the theme “How I got here: Facilitators to engaging in health advocacy.” Data analysis was iterative and collaborative—all but one author participated (M.L., P.L., P.V., M.M.). The results of the analysis informed subsequent data collection—we refined the research questions, developed targeted interview questions, and guided the sampling strategy to obtain a more complete picture of the emerging themes. We ceased data collection when no new information related to the research questions was being gathered.

The University of Toronto research ethics board granted ethics approval to this project.

Results

Our phenomenological approach to the research questions yielded an interesting spectrum of perspectives among participants. After defining the preliminary codes, or units of meaning, we clustered our findings into three main themes: (1) Who I am and what I do: Identity development; (2) How I got here: Facilitators to engaging in health advocacy; and (3) How I continue to be a lifelong health advocate. These themes are listed in Table 1 and described in detail below.

Table 1.

Themes and Subthemes From a Study of the Experiences and Factors That Led 15 Physicians to Be Health Advocates, 2014

Who I am and what I do: Identity development

Participants indicated the importance of deeply ingrained values and ethical commitments, specifically to social justice and care for the vulnerable, which were rooted in their personal experiences. They described a variety of starting points for developing these commitments, including their upbringing, schooling, and specific formative experiences traveling or participating in extracurricular activities.

Participants provided numerous examples of this theme related to their upbringing and early socialization, specifically describing the influence of their parents.

My mother was a Jewish concentration camp victim. And something in her experience and her personality, which I think influenced my personality, led me to an intense identification with the vulnerable and disadvantaged, discriminated against … and then along with that, a feeling that I should try to do something about it. (#015)

Others referred to the early influences of religion or religious schooling: “But also I went to a Catholic school, and it was part of our formation. We had a whole course on social justice, and it was a whole year long” (#007).

In multiple cases, participants described specific, noteworthy, formative experiences, during which they were directly confronted with the suffering of others who were less fortunate than themselves. One participant described the experience of volunteering overseas in a children’s oncology unit as part of a high school extracurricular program: “We were exposed to vulnerable populations. When you’re 16 years old and you’re getting to know children who are dying, it has an impact on you” (#009).

All these experiences collectively contributed to defining participants’ identity as health advocates. Who they were as health advocates was reflective of their understanding of health advocacy and was consistent with the operational definition in the interview guide.1 They articulated in detail the basic idea of actions taken to address the “social, economic, educational, and political changes.”1 Participants described three basic categories of health advocacy: (1) activities extending beyond the health care system to improve the health of individuals (e.g., using community resources to facilitate continuity of care for patients); (2) population health activities to address broad determinants of health (e.g., being part of a collective to advocate to the government for immigrant health); and (3) activities to improve the organization and funding of health care to ensure that patients receive optimal care (e.g., presentations to policy makers). Ultimately, participants considered advocacy to be giving voice to the disenfranchised.

How I got here: Facilitators to engaging in health advocacy

Early engagement and establishment of this work, facilitated by mentorship, training, and organizational support, prepared participants for their health advocate role. Through references to their experiences and history, participants described the factors they thought were important to developing the skills and perspectives needed to transition from an inclination towards health advocacy work to active engagement in such activities.

Most participants described the influence of mentors, not only whether but also how they approached advocacy. Mentors (sometimes physicians, sometimes not) were cited as exemplars, guiding participants’ development and demonstrating how advocacy work could be actualized: “When I got into academic medicine, I had some superb role models, and my role models … were people who would challenge existing beliefs and dogma.… They had a vision about how health care could be better delivered” (#015).

Other participants referred to examples of training, education, and work experience that afforded them the skills and understanding needed for health advocacy work. However, we found no single pattern regarding when or how these skills were developed. In one case, a participant thought that the basic skills needed for advocacy work had been learned in adolescence but were continuously developed through higher education and then practice.

I look to my time in that youth movement, growing up, actually, as being the biggest piece of my training. That was very focused on an empowerment-based educational model for youth.… I carried that forward into what I do. Certainly, some of the basic writing and critical argumentation skills that I got through an arts undergrad degree have been very helpful.… And a lot of other stuff just comes from on the job. (#002)

Participants also highlighted systemic and organizational factors that influenced the extent to which they, or physicians in general, were able to establish health advocacy as a regular part of practice. On a broad policy level, for example, one participant described how political support from major physician organizations provided official sanction of the health advocate role.

The National College, the College of Family Physicians, the Royal College, the Canadian Medical Association all came out with an open letter to the minister asking him to revoke or rescind the cuts. And that makes an incredible difference, to have the legitimacy of Canada’s large health care organizations. It really provides a tremendous amount of support for clinicians who are doing advocacy work. (#003)

At a more immediate level, the organizations and supervisors with whom participants worked encouraged and validated their health advocacy activities. Examples included systems for bestowing recognition, leadership support, and protected time for health advocacy.

Then actually, the chief of my own department, whose primary mentorship to me has been to create space in my workplace for me to do this work, and has validated that it is a legitimate way for me to spend my time in an academic practice plan, meaning I get paid. I’m seen as a contributor to the work of our group. (#001)

How I continue to be a lifelong health advocate

Participants described the factors contributing to their maturation and endurance as health advocates. No single common trajectory to advanced, effective, and enduring advocacy was offered, but some important factors were identified that participants thought made them more able to sustain their advocacy work. Those factors included continuously learning and improving, being self-reflective and self-reflexive, embracing a collaborative effort, and finding intrinsic satisfaction in the work. These elements seemed critical to entrenching participants in their advocacy work, thus sustaining their efforts over time.

First, participants indicated the importance of learning from previous advocacy efforts and continually reinvesting in their commitment to this work.

There’s a concept from the EQ literature that I like, called constructive discontent, and I think that’s important. So to be constructive and positive, but to never be satisfied with where we’re at, and to always be looking for and striving for ways to do things better, and that’s at all of those levels. (#010)

In addition, self-reflection (i.e., critical thinking, personal reflection, and integration of learning) and self-reflexivity (i.e., recognition of one’s social location or place in a situation and how that may affect another in that situation) seemed to foster self-awareness and other awareness that was important for doing this work.

I think that reflective practice is only one very small part of being a reflective person, and I think actually what’s required to be an effective advocate is the ability to reflect upon, not just your individual interactions with patients in terms of one’s own humility, learning from one’s mistakes, and constantly striving to improve. It’s asking questions about how did this person land in my office? What are the broader social factors at play? Thinking of yourself as a citizen as well as a physician, and understanding what your role is in the community. (#001)

Next, key to both effective advocacy and the ability to endure and sustain effort was viewing advocacy as an inherently social endeavor. Participants emphasized the value of collective capacity and provided many examples of the potential impact and influence of collaborative efforts, or as one participant called it, optimizing one’s “coalition of the willing” (#005). For example, “You need to work with people who have complementary strengths, and together you can achieve much more” (#008). For some, the social dimension of advocacy was also the element that made it possible to endure the unavoidable disappointments and stay committed over time.

It’s a lifelong pursuit. For every gain there’s a loss, and for every victory there’s a crushing defeat. If you are in it for the long haul and you really see it as part of your calling as a member of a community, then it’s really important that you not be alone. (#001)

Finally, just as deep-seated motivations were discussed in the context of how participants first became interested in health advocacy, so too were they described in relation to the capacity and willingness to sustain one’s advocacy work. In one case, a participant described how the motivation to do this work was fueled by the intrinsic satisfaction it engendered. This example highlights the role of innate or deep-rooted drives and passions, and the potential to increase and perpetuate engagement through experience.

I find it, in many ways, the most satisfying part of what I do. It challenges me intellectually. It challenges me creatively. It is exciting … it is addictive once you really get into it.… And this advocacy work helps me feel like I am doing something about that and pushing medicine and pushing health care towards something that I think actually has a better impact on health than much of the other stuff that I do. So, I couldn’t imagine practicing medicine without this, and I get huge satisfaction from doing it. (#002)

Discussion

Through a series of interviews, we explored the experiences and factors that physician health advocates identified as formative and influential. They described the factors that contributed to the development of their health advocate identity (i.e., exposure to social injustice, upbringing, schooling, and formative experiences while traveling or participating in extracurricular activities) and those that facilitated their engagement in health advocacy work (i.e., mentors, training, systemic and organizational supports). Participants also highlighted continuous learning and improvement, self-reflection and self-reflexivity, collaboration, and intrinsic satisfaction in the work as ways to sustain and grow their role as lifelong health advocates. This understanding of physicians’ experiences of their health advocacy work has implications for the growing imperative in medical education to support competency in health advocacy.3 In particular, our results suggest that adopting a developmental perspective of health advocacy work (i.e., exploring aspects of identity, exploiting motivations to engage and ideas of how to get there, and promoting ways to continue in this role) may be a worthwhile pedagogical approach to developing this commitment in physicians.

Our findings suggest that participants developed their health advocate identity in stages. This model is significant, in part, because curricular strategies can be designed in accordance with developmental stages. Our results suggest that the selection process for medical school candidates could consider applicants’ social justice values. The qualitative study by Mu et al6 suggests that early exposure to social injustice, parental influences, role modeling, and internal motivators are inspirations for pursuing health advocacy work. Our study supports these findings. While applicants’ past advocacy experiences and motivation to become doctors already come into play in admissions decisions, prior exposure to vulnerable populations and having a broad understanding of advocacy also could be considered.

Participants in another study conceived of health advocacy as encompassing efforts to address individuals’ needs outside of the health care system and social determinants of health at the population level.11 Our findings build on this conceptualization by including physicians’ efforts to improve the organization and funding of health care. By accepting applicants who acknowledge the importance of empathizing and lending a voice to the disempowered, then by providing them with the tools they need to work toward these goals, schools could increase the likelihood that graduates will be committed to health advocacy throughout their careers. For those students not already thus inclined or for those who lack sufficient prior exposure to the prerequisite experiences, education may ignite an initial spark of awareness and passion.

Medical schools and training programs also can help students and trainees to establish a career that prioritizes advocacy (i.e., engagement) by teaching the practical skills needed to do this work. The facilitators described by our participants—namely, health advocacy mentorship, education about health care and the social determinants of health, and training in skills that may otherwise be neglected in medical education—could be incorporated into the curriculum, guided by a learner-centered approach to education. For example, teaching about power, language genres, and legislative and health care systems could encourage students to become health advocates. Additionally, fostering space for mentors and role models with an inclination towards advocacy is critical. Making advocacy a true professional commitment can be challenging when institutions pressure individuals to pursue other paths.

Finally, for physicians with more experience as advocates, interventions could teach the more refined skills needed to sustain a commitment to this work. This might include teaching physicians how to be reflective and reflexive. Teaching these skills to students, given the known benefits of providing respectful and empathic medical care, is becoming more common.12,13 Moreover, promoting a collaborative approach, as recommended by our participants, may make pursuing the role of health advocate less daunting.14 The conceptualization of the health advocate role as a collective partnership may make it more attainable, both for individual physicians and the profession generally. Providing exposure to the rewards of health advocacy work through hands-on learning opportunities throughout a physician’s career may help to build positive attitudes and a commitment to these activities. Although residents think that health advocacy is important during training and in future practice, they generally fail to take an active role in this work.15 Despite their awareness of and interest in this role, clear objectives and formal training in health advocacy are absent or inadequate.15,16 Experiential learning exercises and community service learning opportunities coupled with critical reflection may be useful as a means of offering education on abstract issues as well as tangible encounters with the real, human consequences of social disparity to foster a sense of social responsibility in trainees.17,18

Our study has a few notable limitations. It was conducted with a small group of physicians representing only family medicine and a few other disciplines. Moreover, recruitment was based on identifying individuals who worked in health advocacy according to the specific definition we used. Consequently, we may have missed important perspectives from physicians who do not identify themselves as health advocates or who are not identified by their peers as such, but who are nevertheless engaged in work that is consistent with this role. The relevance of our findings also may be limited by demographic variables, such as the country of medical education.

As our sample was very specific, it was ideal for this initial work. However, further inquiry is needed. Future research could explore the perspectives of other disciplines (e.g., surgery) and of physicians who do not identify themselves, or are not identified by their peers, as health advocates, so as to capture the experiences of different groups and contexts. Another topic for additional research would be to further explore how our recommendations for supporting physicians’ development and ongoing engagement as health advocates might apply to other physician roles, such as scholars or leaders. Finally, our study posited that particular barriers to pursuing health advocacy work exist and that they warrant special attention. For example, a recent literature review revealed that educators and learners consider the health advocate role to be among the least relevant to clinical practice and among the most challenging to teach and assess.19 Inadequate published material, lack of clarity within the role itself, a scarcity of explicit role modeling in practice, and the absence of a gold standard for assessment were highlighted as barriers affecting health advocacy education.19 Thus, future work could determine if our recommendations are unique to the health advocate role or apply to other roles as well.

Our study explored the many factors that allow physicians to establish and sustain a working commitment to health advocacy. Medical schools have a responsibility to optimize these factors and to expand how they teach students to be good health advocates and thus good doctors.

Footnotes

Funding/Support: None reported.

Other disclosures: None reported.

Ethical approval: This project received ethical approval from the University of Toronto research ethics board (protocol reference number #30011).

Previous presentations: (1) Law M, Leung P, Veinot P, Mylopoulos M. Health advocacy: The relentless pursuit of collective victory. Oral presentation at the Canadian Conference on Medical Education, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, April 25–28, 2015. (2) Leung P, Law M, Veinot P, Mylopoulos M. Health advocacy: The relentless pursuit of collective victory. Poster presentation at the Family Medicine Forum, Quebec City, Quebec, Canada, November 12–15, 2014.

References

- 1.Earnest MA, Wong SL, Federico SG. Perspective: Physician advocacy: What is it and how do we do it? Acad Med. 2010;85:63–67. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c40d40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frank JR, Snell L, Sherbino J, editors. CanMEDS 2015 Physician Competency Framework. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sherbino J, Bonnycastle D, Côte B, et al. The CanMEDS 2015 Health Advocate Expert Working Group Report. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Medical Association. Declaration of Professional Responsibility: Medicine’s Social Contract With Humanity. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association; 2001. http://www.ama-assn.org/resources/doc/ethics/decofprofessional.pdf. Accessed January 26, 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.ABIM Foundation, ACP-ASIM Foundation, European Federation of Internal Medicine. Medical professionalism in the new millennium: A physician charter. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:243–246. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-3-200202050-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mu L, Shroff F, Dharamsi S. Inspiring health advocacy in family medicine: A qualitative study. Educ Health (Abingdon) 2011;24:534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Komaromy M, Lurie N, Bindman AB. California physicians’ willingness to care for the poor. West J Med. 1995;162:127–132. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crandall SJ, Volk RJ, Loemker V. Medical students’ attitudes toward providing care for the underserved. Are we training socially responsible physicians? JAMA. 1993;269:2519–2523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sokolowski R. Introduction to Phenomenology. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stewart D, Mickunas A. Exploring Phenomenology: A Guide to the Field and Its Literature. Chicago, IL: American Library Association; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hubinette MM, Ajjawi R, Dharamsi S. Family physician preceptors’ conceptualizations of health advocacy: Implications for medical education. Acad Med. 2014;89:1502–1509. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Charon R. The patient–physician relationship. Narrative medicine: A model for empathy, reflection, profession, and trust. JAMA. 2001;286:1897–1902. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.15.1897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sandars J. The use of reflection in medical education: AMEE guide no. 44. Med Teach. 2009;31:685–695. doi: 10.1080/01421590903050374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hubinette M, Dobson S, Voyer S, Regehr G. “We” not “I”: Health advocacy is a team sport. Med Educ. 2014;48:895–901. doi: 10.1111/medu.12523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leveridge M, Beiko D, Wilson JW, Siemens DR. Health advocacy training in urology: A Canadian survey on attitudes and experience in residency. Can Urol Assoc J. 2007;1:363–369. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hakim J, Black A, Gruslin A, Fleming N. Are Canadian postgraduate training programs meeting the health advocacy needs of obstetrics and gynaecology residents? J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2013;35:539–546. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(15)30913-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dharamsi S, Richards M, Louie D, et al. Enhancing medical students’ conceptions of the CanMEDS health advocate role through international service–learning and critical reflection: A phenomenological study. Med Teach. 2010;32:977–982. doi: 10.3109/01421590903394579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dharamsi S, Espinoza N, Cramer C, Amin M, Bainbridge L, Poole G. Nurturing social responsibility through community service–learning: Lessons learned from a pilot project. Med Teach. 2010;32:905–911. doi: 10.3109/01421590903434169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Poulton A, Rose H. The importance of health advocacy in Canadian postgraduate medical education: Current attitudes and issues. Can Med Educ J. 2015;6:e54–e60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]