ABSTRACT

Infections with H7 highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) viruses remain a major public health concern. Adaptation of low-pathogenic H7N7 to highly pathogenic H7N7 in Europe in 2015 raised further alarm for a potential pandemic. An in-depth understanding of antibody responses to HPAI H7 virus following infection in humans could provide important insight into virus gene expression as well as define key protective and serodiagnostic targets. Here we used whole-genome gene fragment phage display libraries (GFPDLs) expressing peptides of 15 to 350 amino acids across the complete genome of the HPAI H7N7 A/Netherlands/33/03 virus. The hemagglutinin (HA) antibody epitope repertoires of 15 H7N7-exposed humans identified clear differences between individuals with no hemagglutination inhibition (HI) titers (<1:10) and those with HI titers of >1:40. Several potentially protective H7N7 epitopes close to the HA receptor binding domain (RBD) and neuraminidase (NA) catalytic site were identified. Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) analysis identified a strong correlation between HA1 (but not HA2) binding antibodies and H7N7 HI titers. A proportion of HA1 binding in plasma was contributed by IgA antibodies. Antibodies against the N7 neuraminidase were less frequent but targeted sites close to the sialic acid binding site. Importantly, we identified strong antibody reactivity against PA-X, a putative virulence factor, in most H7N7-exposed individuals, providing the first evidence for in vivo expression of PA-X and its recognition by the immune system during human influenza A virus infection. This knowledge can help inform the development and selection of the most effective countermeasures for prophylactic as well as therapeutic treatments of HPAI H7N7 avian influenza virus.

IMPORTANCE An outbreak of pathogenic H7N7 virus occurred in poultry farms in The Netherlands in 2003. Severe outcome included conjunctivitis, influenza-like illness, and one lethal infection. In this study, we investigated convalescent-phase sera from H7N7-exposed individuals by using a whole-genome phage display library (H7N7-GFPDL) to explore the complete repertoire of post-H7N7-exposure antibodies. PA-X is a recently identified influenza virus virulence protein generated by ribosomal frameshifting in segment 3 of influenza virus coding for PA. However, PA-X expression during influenza virus infection in humans is unknown. We identified strong antibody reactivity against PA-X in most H7N7-exposed individuals (but not in unexposed adults), providing the first evidence for in vivo expression of PA-X and its recognition by the immune system during human infection with pathogenic H7N7 avian influenza virus.

INTRODUCTION

Avian influenza viruses (AIVs) are mostly restricted to aquatic birds. On occasion, they acquire the capacity to directly infect the respiratory tract of poultry and mammals. Such cross-species transmission often results in a large number of sick birds (chickens and turkeys), as was reported for H7N1 viruses in Italy in 1999, H7N3 viruses in Canada in 2004, H7N7 viruses in Spain in 2009, H5N8 viruses in the United States, and the recent adaptation of H7N7 viruses from low-pathogenic avian influenza (LPAI) virus to highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) virus in the UK and Germany in 2015 (1, 2). Infection of humans with AIV resulting in high morbidity and mortality rates was reported for HPAI H5N1 (3), HPAI H7N7 (4–6), and H7N9 (7) viruses. Due to the absence of preexisting immunity against avian influenza viruses among human populations, such viruses pose a serious threat of a global pandemic if they further adapt for human-to-human transmission. These adaptations include specific mutations in the hemagglutinin (HA), neuraminidase (NA), and internal genes as well as viral proteins that evolved to dampen host innate responses to the virus (8).

An outbreak of HPAI H7N7 virus occurred in commercial poultry farms in The Netherlands between February and March 2003. Transmissions to farm workers (including farm holders, family, and professional screeners and cullers) occurred, with 349 individuals reporting symptoms of conjunctivitis and 90 individuals reporting symptoms of influenza-like illness. Viruses isolated from the eyes confirmed the presence of H7N7 HPAI (A/Netherlands/33/03) viruses, which were identical to the viruses isolated from sick poultry (4–6). Hemagglutination inhibition (HI) titers in sera from H7N7-exposed individuals were relatively low (9). This may have reflected the unique site of infection and/or a naive immune status that could not elicit strong neutralizing antibodies against HPAI H7N7 virus. Using an HI cutoff value of >10, type A H7 hemagglutinin [A(H7)]-positive titers were detected in 85% of 34 H7N7-infected persons, 51% of 469 individuals exposed to infected poultry, and 64% of those exposed to H7N7-infected persons (9). However, there is a lack of knowledge on the quality of the polyclonal antibody (Ab) responses generated following natural HPAI H7N7 virus infection and how these antibodies protect against severe disease. Current efforts to develop an effective vaccine against H7N7 are hampered by the paucity of information on protective immune responses and poor immune responses in persons vaccinated with either inactivated or live H7N7 vaccines (10–12).

We previously used whole-genome gene fragment phage display libraries (GFPDLs) spanning the entire genome of HPAI H5N1 A/Vietnam/1203/2004 virus that expresses large HA inserts representing conformational epitopes that are recognized by several broadly neutralizing human monoclonal antibodies to analyze the antibody repertoires of postvaccination sera and convalescent-phase sera from H5N1-infected individuals (13, 14).

In this study, we generated a GFPDL from H7N7 A/Netherlands/33/03 to evaluate serum samples from 15 individuals exposed to HPAI H7N7 virus and with different HI titers, as determined previously (9). Since the phage libraries were constructed from the whole influenza virus genome, they potentially displayed every possible known or unknown viral protein segment with a size ranging between 15 and 350 amino acids (aa) on the phage surface protein. The serum samples were evaluated separately by a GFPDL encompassing the H7-HA gene, the N7-NA gene, and the six internal genes to identify the majority of linear and conformational epitopes in an unbiased comprehensive approach for epitope mapping of the human polyclonal antibody response. We also used real-time surface plasmon resonance (SPR)-based kinetics for measurement of total antibody binding to H7-HA1, H7-HA2, and N7-NA as well as antibody isotype analysis and determination of dissociation rates as a surrogate of antibody affinity in post-H7N7-exposure polyclonal plasma.

Surprisingly, we observed strong antibody binding to the recently identified PA-X protein in 14/15 plasma samples from H7N7-exposed cases. The PA-X protein is generated by ribosomal frameshifting in segment 3 of type A influenza virus that codes for PA (15). This protein was postulated to play an important role in virus replication and shutoff of host innate responses in animal models, but its expression during natural influenza virus exposure in humans is unknown (16–18). This is the first report of the recognition of PA-X by the immune system during natural infection with avian influenza virus in humans.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Description of H7N7-exposed subjects and determination of HI titers.

Sera were obtained from persons on average 22 weeks after exposure to the HPAI H7N7 virus (9). One of the serum samples was obtained from a person with H7N7 infection confirmed by PCR and virus isolation (PCR and culture from conjunctiva swabs) (4). All serum samples from the 15 individuals exposed to H7N7-infected poultry in this study had H7-HA1 globular head domain binding antibodies, confirming their H7N7 exposure status, irrespective of their HI titers. For HI tests, individual plasma samples were treated with receptor-destroying enzyme (RDE) followed by an inactivation step at 56°C for 30 min, tested for H7N7 (A/Netherlands/33/03) virus by using horse red blood cells (RBCs), and tested for seasonal H3N2 (A/Panama/2007/99) and H1N1 (A/New Caledonia/20/99) viruses by using turkey RBCs; details were described previously (9). A neutralization assay was also conducted with appropriate positive controls, including chicken anti-H7N1 and human sera against seasonal strains. However, none of the human sera from subjects who were exposed to H7N7 and who had confirmed infection showed neutralization of the A/H7N7 virus in the microneutralization assay in MDCK cells (9).

Control adult sera were obtained after the 2009 H1N1 pandemic from U.S. individuals born between 1980 and 1990 with HI titers of >40 against the seasonal H1N1, H3N2, and H1N1pdm09 strains (19). The vaccination history of the subjects was not confirmed, but they all had HI titers against circulating influenza virus strains, suggesting prior exposure to seasonal influenza.

The study at CBER, FDA, was conducted with deidentified samples under Research Involving Human Subjects (RIHSC) exemption 03-118B, and all assays performed fell within the permissible usages in the original consent.

Construction of H7N7 gene-fragmented phage display libraries.

cDNAs corresponding to all eight gene segments of H7N7 A/Netherlands/33/03 were generated from RNA prepared from HPAI H7N7 virus isolated from an infected human and used for cloning. fSK-9-3 is a gIIIp display-based phage vector where the desired polypeptide can be expressed as a gIIIp fusion protein.

Phage display libraries were constructed individually for the HA (H7-GFPDL-HA) and NA (H7-GFPDL-NA) genes and the rest of the six gene segments (PB2, PB1, PA, NP, M, and NS), referred to as H7-GFPDL-6. Purified DNAs containing HA, NA, or an equimolar ratio of the six genes (H7-GFPDL-6) were digested with a DNase shotgun cleavage kit (Novagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions to obtain DNA fragments for each of the three gene segment pools and used for GFPDL construction. Since the phage libraries were constructed from the whole influenza virus genome, they potentially display every possible known or unknown viral protein segment with a size ranging between 15 and 350 amino acids encoded by the influenza virus genome on the phage surface gIII protein.

Affinity selection of H7N7 GFPDL phages with polyclonal human sera following exposure to HPAI H7N7 virus.

Prior to panning of the GFPDL with polyclonal serum antibodies, serum components that could nonspecifically interact with phage proteins were removed by incubation with UV-killed M13K07 phage-coated petri dishes. Subsequent GFPDL affinity selection was carried out in solution (with protein A/G).

For H7-GFPDL-HA panning using sera from humans following exposure to HPAI H7N7 virus, equal volumes of serum samples from subjects with H7 HI titers of 1:160 or <10 were pooled separately. For GFPDL panning of human sera following H7N7 exposure using H7-GFPDL-NA and H7-GFPDL-6, equal volumes of sera from all individuals were pooled. GFPDL selection was carried out in solution (with protein A/G) (13).

Generation of H7-HA1 and -HA2 domains.

Synthetic DNAs encoding HA1 (positions 1 to 320) and HA2 (positions 331 to 540) of H7N7 A/Netherlands/33/03 (identical to HA from A/Netherlands/219/03) were cloned, expressed, and purified as previously described (20). Escherichia coli BL21 cells (Novagen) were used for expression. Following expression, inclusion bodies (IBs) were isolated by cell lysis and multiple washing steps with 1% Triton X-100. Final IB pellets were resuspended in denaturation buffer and centrifuged to remove residual debris. For refolding, supernatants were slowly diluted in redox folding buffer. The refolded proteins were dialyzed against 20 mM Tris HCl (pH 8.0) to remove the denaturing agents. The dialysates were filtered through a 0.45-μm filter and subjected to purification by HisTrap Fast flow chromatography. HA1 proteins were properly folded and contained a high percentage of functional oligomers (20).

Antibody kinetics measurements of polyclonal serum antibodies following H7N7 exposure by surface plasmon resonance.

Steady-state equilibrium binding of individual human sera following H7N7 exposure was monitored at 25°C by using a ProteOn surface plasmon resonance biosensor (Bio-Rad). Antibody isotyping for human antibodies bound to specific proteins was performed by injecting anti-human Ig-isotyping antibodies (Sigma) in the same SPR experimental run. The recombinant HA globular head domain (rHA1-His6) or stalk domain (rHA2-His6) or NA proteins were coupled to a GLC sensor chip. The spatial density of antigen (Ag) on the chip surface was adjusted to measure only monovalent antibody interactions in the polyclonal sera. Antibody dissociation constants that describe the stability of the Ab-Ag complex, i.e., the fraction of complexes that decays per second, were determined directly from the serum sample interaction with H7-rHA1 (positions 1 to 320), H7-rHA2 (positions 331 to 514), N7-NA proteins, and synthetic influenza virus peptides by using SPR in the dissociation phase (600 s) and calculated by using Bio-Rad ProteOn manager software for the heterogeneous sample model as described previously (14). The dissociation constants were determined from two independent SPR runs.

Statistical analysis.

Correlations were tested by Pearson correlation analysis and confirmed by Spearman correlation analysis. P values of <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

HI titers for HPAI H7N7 virus-exposed cases and elucidation of HA epitopes following H7N7 exposure using a GFPDL.

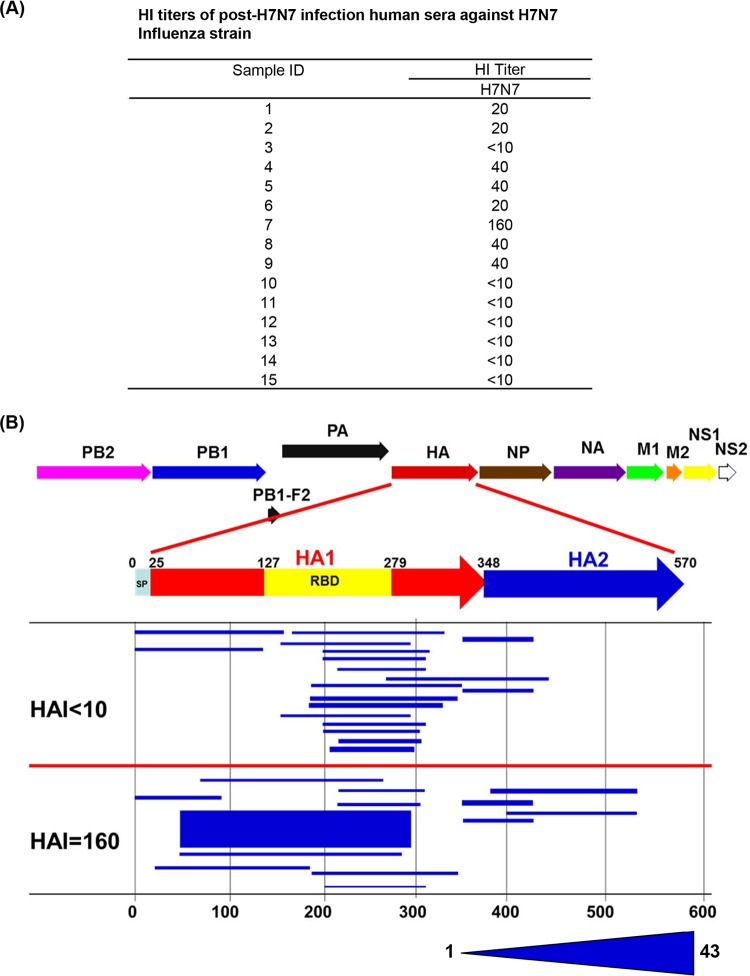

We evaluated serum samples from 15 selected HPAI H7N7 virus-exposed cases during the 2003 influenza outbreak in The Netherlands (9). As shown in Fig. 1A, HI titers of ≥20 against H7N7 were found in only 8/15 exposed individuals, and the titers were in the low-to-modest range. The single laboratory culture confirmed that the H7N7-infected case (case 4) had an HI titer of 40 against H7 virus. The lower antibody response might be due to a naive primary response to H7N7 virus or may reflect the fact that the HPAI H7N7 virus was associated primarily with conjunctivitis, and virus was isolated from the eyes (usually an immune-privileged site) and much less frequently from nasal swabs. In addition, the blood samples were obtained during the convalescent phase on average 22 weeks after HPAI H7N7 virus exposure.

FIG 1.

Elucidation of the epitope profile of the H7 HA protein recognized by antibodies in individuals following HPAI H7N7 virus exposure in The Netherlands. (A) Distribution of serum HI titers against H7N7 (A/Netherlands/33/03) in 15 individuals following exposure to HPAI H7N7 virus. (B) Alignment of peptides recognized by pooled sera from H7N7-exposed individuals identified by using an H7-HA GFPDL to the H7 HA translated sequence. The HA1 RBD is depicted in yellow. The amino acid designation is based on the HA protein sequence. Graphical distribution of representative clones with a frequency of ≥2, obtained after affinity selection, is shown. The horizontal position and the length of the bars indicate the peptide sequence displayed on the selected phage clone with its homologous sequence in the influenza virus HA protein upon alignment. The thickness of each bar represents the frequency of repetitively isolated phage, with the scale shown below the alignment.

The GFPDL analysis was conducted with three separate phage display libraries expressing epitopes of 15 to 350 amino acids covering the H7-HA gene, the N7-NA gene, and all 6 internal genes from the H7N7 (A/Netherlands/33/03) virus with at least 106 unique clones in each phage library to display all possible linear and conformational epitopes. For the HA-GFPDL analysis, pooled samples with HI titers of <10 were compared to the sample from individual 7 with an HI titer of 160 to investigate the differential responses. The total numbers of phages bound were 2-fold higher for the sample with an HI titer 160 than for pooled serum samples with an HI titer of <10, suggesting the presence of HA binding antibodies even in the absence of HI titers. The thickness of the bars in Fig. 1 represents the frequency of identical phage clones isolated during GFPDL panning. As depicted in Fig. 1B, the epitope distributions were different for the two groups. The serum samples with an HI tier of <10 bound primarily to phages expressing fragments mapping to the C terminus of H7-HA1 and to fewer epitopes in the N termini of HA1 and HA2. These regions of HA1 do not contain known neutralization targets that are measured in HI assays. In contrast, the serum sample from the individual with an HI titer of 160 bound a large number of long epitopes encompassing the entire receptor binding domain (RBD).

Real-time antibody binding kinetics for polyclonal plasma obtained following H7N7 exposure with recombinant H7-HA1 and H7-HA2 domains, antibody affinity, and immunoglobulin isotypes determined by using SPR.

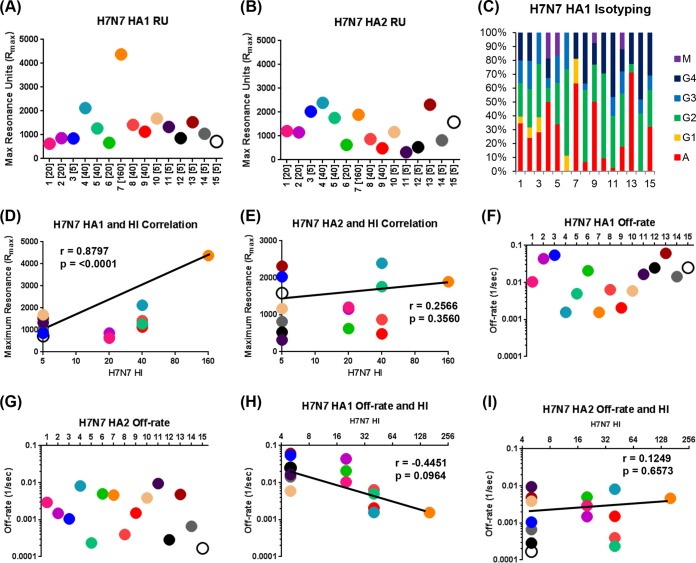

H7-HA1 oligomers were produced in E. coli. They were previously shown to be functional by hemagglutination and induction of protective immunity in ferrets (20). In this study, SPR chips coated with either H7-HA1 or H7-HA2 domains were used for analysis of total antibody binding (maximum resonance units [RU]) using 15 individual plasma samples obtained following H7N7 exposure (Fig. 2A and B). The antibody affinity for each sample was measured by using dissociation rates of antigen-antibody complexes (Fig. 2F and G). All serum samples bound to both HA1 and HA2 domains with various antibody reactivity profiles. These data, especially for H7-HA1 binding, confirmed that, indeed, all 15 individuals were exposed to H7N7, including those with HI titers of <10. Sera from H7-unexposed individuals who were enrolled in a previous study of an H7N7 vaccination clinical trial did not react against the H7-HA1 domain (12), confirming the specificity of SPR binding and excluding anti-HA1 antibody cross-reactivity due to prior exposure to seasonal influenza virus strains. A significant correlation was observed between the H7N7 HI titers and total antibody binding to H7-HA1 (r = 0.8797; P < 0.0001) (Fig. 2D) but not with antibody binding to the H7-HA2 domain (Fig. 2E).

FIG 2.

Total antibody binding, antibody isotype, and affinity of polyclonal plasma for H7-HA1 and HA2 proteins in HPAI H7N7 virus-exposed subjects. (A and B) Steady-state equilibrium analysis of the total binding antibodies to properly folded functional H7-HA1 (A) or H7 HA2 (B) in polyclonal human sera was measured by SPR. HI titers are shown in parentheses for each subject. Dots represent data for serum samples obtained following H7N7 exposure that were diluted 10-fold or 100-fold and injected simultaneously onto H7-HA1 or H7-HA2 immobilized on a sensor chip through the free amine group and onto a blank flow cell free of peptide. Maximum resonance unit (RU) values for antibody binding are shown for individual H7N7-exposed subjects. (C) Isotype of serum antibodies bound to H7-HA1 for sera obtained following H7N7 exposure. Data shown are the mean percent contributions of each isotype to total HA1 binding in individual samples from two independent experiments. (D and E) Total binding antibodies (maximum RU) against H7-HA1 (D) or H7-HA2 (E) in human sera obtained following H7N7 exposure were correlated with the homologous H7N7 virus HI titers. Spearman correlations are reported for the calculation of correlations between total anti-HA1 antibody binding to HA1 (D) or HA2 (E) and HI titers combined across all individuals. The color scheme in panels D and E is the same as that in panels A and B. (F and G) Antibody avidity measurements in polyclonal sera by off-rate constants determined by using SPR. Antibody off-rate constants, which describe the stability of the antigen-antibody complexes, were determined directly from polyclonal serum sample interactions with H7-HA1 (F) or H7-HA2 (G) proteins by using SPR in the dissociation phase and provide a measure of net binding affinity. For accurate measurements, parallel lines in the dissociation phase for the 10-fold and 100-fold dilutions for each human serum sample were required. The off-rate constants were determined from two independent SPR runs. (H and I) Serum antibody off-rate constants for infected individuals (each symbol indicates results for one individual) were plotted. Correlation statistics of affinity measurements and off-rate constants of antibody binding to H7-HA1 (H) or H7-HA2 (I) with H7N7 HI titers did not reach statistical significance.

Isotype analysis of the HA1 binding antibodies demonstrated representation of all isotypes (IgA, IgG, and IgM) and IgG subtypes (Fig. 2C), which is likely the outcome of active H7N7 infection. This is in contrast to serum antibody responses to an H7N7 vaccine administered intramuscularly, which were predominated by IgG, with minimal or no IgA contribution (12).

We also measured the antigen-antibody complex dissociation rates of H7-HA1- and H7-HA2-bound plasma antibodies as a surrogate for antibody affinity, as previously described (14). It was found that the antibody off-rates for HA1 binding ranged between 10−2 and 10−3 per s, while binding to HA2 showed stronger affinity, with off-rates ranging between 10−3 and 10−4 per s (Fig. 2F and G). This high-affinity binding to H7-HA2 may represent recall responses due to cross-reactivity with seasonal H3N2 viruses, as was observed in the recent H7N7 vaccination clinical trial in U.S. adults (12). We observed a positive correlation between the H7-HA1 antibody dissociation rates and the H7N7 HI titers, but the trend did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 2H). No such trend was observed between H7-HA2 antibody dissociation rates and H7N7-HI titers (Fig. 2I).

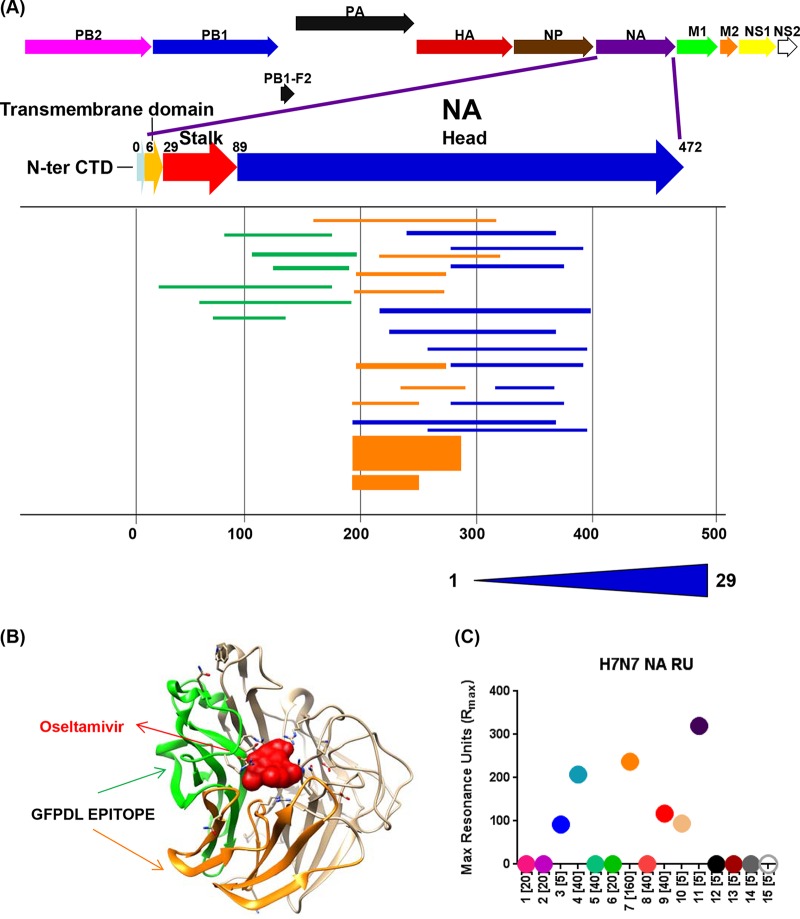

Antibody repertoire for N7-NA epitopes following H7N7 exposure.

To identify all the NA epitopes recognized by antibodies generated following H7N7 exposure, we used the N7-NA GFPDL with the pooled serum samples (Fig. 3A). Diverse epitopes spanning primarily the NA ectodomain were identified. The predominant epitopes in the N-terminal half of the ectodomain (residues 105 to 193 and 194 to 270) (Fig. 3B, green and orange, respectively) mapped close to the sialic acid binding site on the structure of N7-NA (Fig. 3B). To quantify the individual antibody responses to NA, SPR was performed with a functionally active N7-NA molecule. However, N7-NA binding antibodies were measured in only 6/15 plasma samples in this SPR analysis (Fig. 3C). Interestingly, only three NA-reactive serum samples had HI titers of 40 (individuals 4 and 9) or 160 (individual 7), while the other three had HI titers of <10 (individuals 3, 10, and 11). The culture-confirmed infected plasma from subject 4 (with an HI titer of 1:40) showed good binding to H7N7-HA1 (Fig. 2A) and to NA (Fig. 3C). Therefore, in general, the antibody responses to the H7-HA and NA surface proteins were not linked in these H7N7-exposed individuals or decayed at different rates following H7N7 exposure.

FIG 3.

Epitope repertoire of N7-NA-specific antibodies generated following H7N7 exposure. (A) Schematic alignment of the phage-displayed epitopes in N7-NA recognized by antibodies in pooled plasma obtained following H7N7 exposure. Peptides were identified by panning with an H7N7-NA GFPDL and were aligned to the N7-NA translated sequence. The amino acid designation is based on the NA protein sequence. Bars indicate identified inserts, and the 3 different antigenic domains selected from epitope mapping are depicted as green, orange, and blue bars. The thickness of each bar represents the frequency of repetitively isolated phage inserts (only clones with a frequency of 2 or more are shown), and the scale is shown below the alignment. CTD, C-terminal domain. (B) The conformational epitope in NA (NA residues 105 to 193) (green) and the immunodominant epitope (NA residues 194 to 270) (orange) are shown on the monomeric N7-NA structure (PDB accession number 4QN7), with bound oseltamivir shown in red. (C) Steady-state equilibrium of total binding of antibodies in polyclonal human sera to properly folded functional N7-NA was measured by SPR (HI titers for each subject are shown in brackets). Dots represent data for individual serum samples obtained following H7N7 exposure that were diluted 10-fold and injected simultaneously onto N7-NA immobilized on a sensor chip through the free amine group and onto a blank flow cell free of peptide. Maximum RU values for antibody binding are shown for individual H7N7-infected subjects. Data shown are the means from two independent experiments.

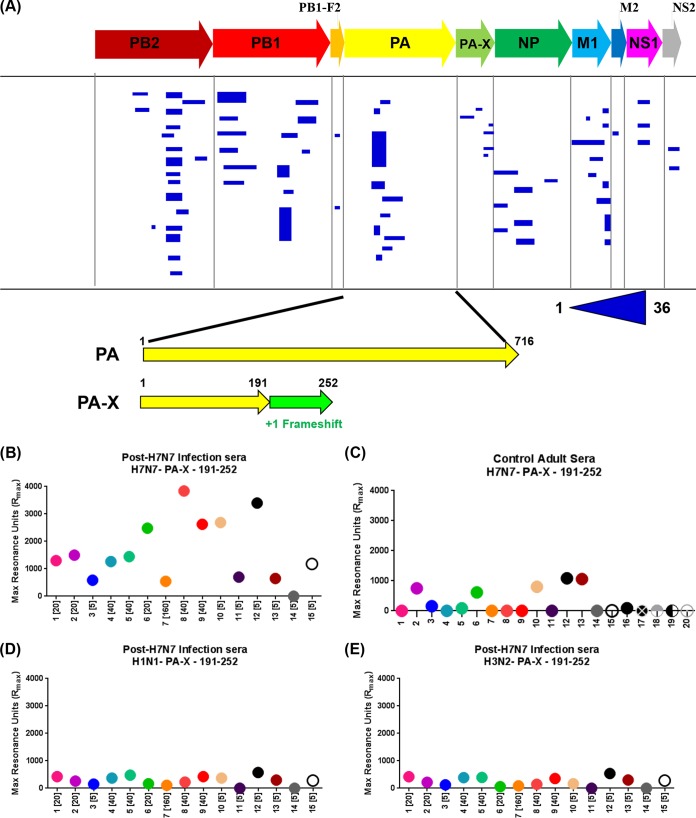

Epitome of the internal six genes of H7N7: evidence for antibodies targeting PA-X following H7N7 exposure.

The pooled sera obtained following H7N7 infection from all 15 individuals were used for panning of H7-GFPDL-6 displaying gene segments of 15 to 350 residues across all six internal genes (Fig. 4A). Binding to multiple diverse epitopes was observed for all the known proteins encoded by the internal genes. Only clones with a frequency of 2 or more are shown in Fig. 4A. Surprisingly, multiple clones binding to an epitope specific to the C terminus of PA-X, which does not overlap the PA protein, were selected by phage display. PA-X is a protein consisting of the amino-terminal 191 amino acids of PA fused to the unique 61 amino acids that result from ribosomal frameshifting (15). To investigate the frequency and magnitude of PA-X antibody reactivity in individual serum samples, we measured the binding of the 15 serum samples obtained following H7N7 exposure to a synthetic PA-X peptide sequence (residues 191 to 252) containing the C-terminal PA-X unique epitope (aa 192 to 252) identified by phage display using SPR. To our surprise, the majority of the serum samples (14/15) showed very high antibody binding to the PA-X peptide of H7N7 (average maximum RU of 1,612.5) (Fig. 4B). In parallel, we ran samples from 20 adults (exposed to/infected with H1N1pdm09 during the 2009 influenza pandemic) (19). All of these individuals had high HI titers against multiple seasonal influenza virus strains in addition to H1N1pdm09. We found either no binding (15/20 samples) or low binding (5/15) to the H7N7 PA-X peptide (average maximum RU of 232.1) (Fig. 4C). To establish the specificity of PA-X peptide binding, all human samples obtained following H7N7 exposure were also analyzed against PA-X peptides derived from seasonal H1N1 and H3N2 strains by SPR (Fig. 4D and E and 5). Only low-level antibody binding to both H1N1 and H3N2 PA-X peptides was observed with serum samples from H7N7-exposed individuals.

FIG 4.

Antibody epitopes in H7N7 internal proteins (H7-GFPDL-6) recognized by pooled sera from H7N7-exposed individuals and immune response to PA-X. (A) Schematic alignment of the identified epitopes recognized by antibodies in pooled polyclonal sera from H7N7-exposed individuals by using GFPDLs (H7-GFPDL-6) expressing all internal proteins of influenza H7N7 A/Netherlands/33/03 virus. Graphical distributions of representative clones with a frequency of ≥2 obtained after affinity selection are shown. The horizontal position and the length of the bars indicate the alignment of the peptide sequence displayed on the selected phage clone to its homologous sequence in the corresponding influenza virus protein. The thickness of each bar represents the frequency of repetitively isolated phage, with the scale shown below the alignment. The amino acid designation is based on PA, and the PA-X protein sequence shows the common N-terminal sequence between PA and PA-X and the unique 61-amino-acid sequence at the C termini of PA-X due to ribosomal frameshifting. (B, D, and E) Reactivity of serum antibodies from 15 individual H7N7-exposed subjects against a synthetic PA-X peptide (aa 191 to 252) derived from the unique PA-X (aa 192 to 252) protein sequence from H7N7 (B), seasonal H1N1 (D), or seasonal H3N2 (E) determined by an SPR assay. (C) Reactivity of serum antibodies from 20 U.S. adults (exposed to H1N1pdm09) against the same synthetic H7N7 PA-X peptide.

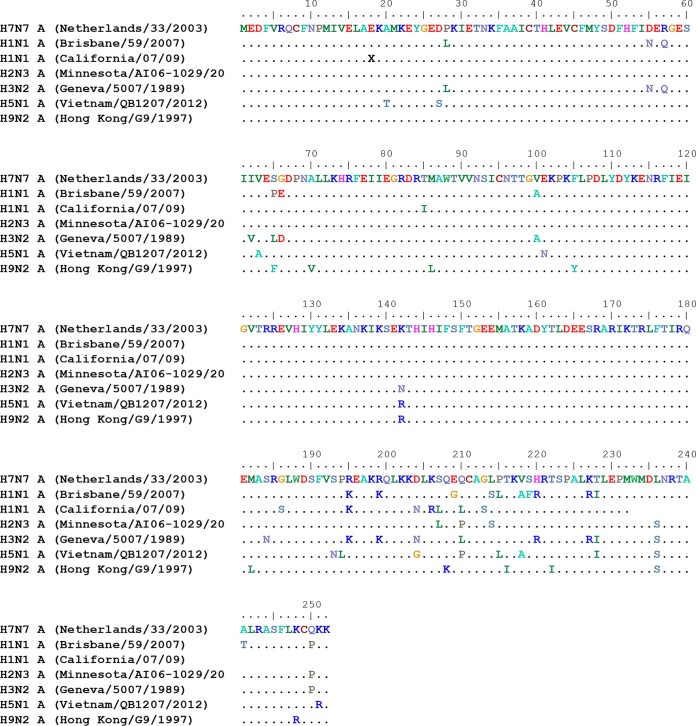

FIG 5.

Alignment of the PA-X protein sequence of the H7N7 A/Netherlands/33/03 strain with multiple seasonal and avian influenza virus strains.

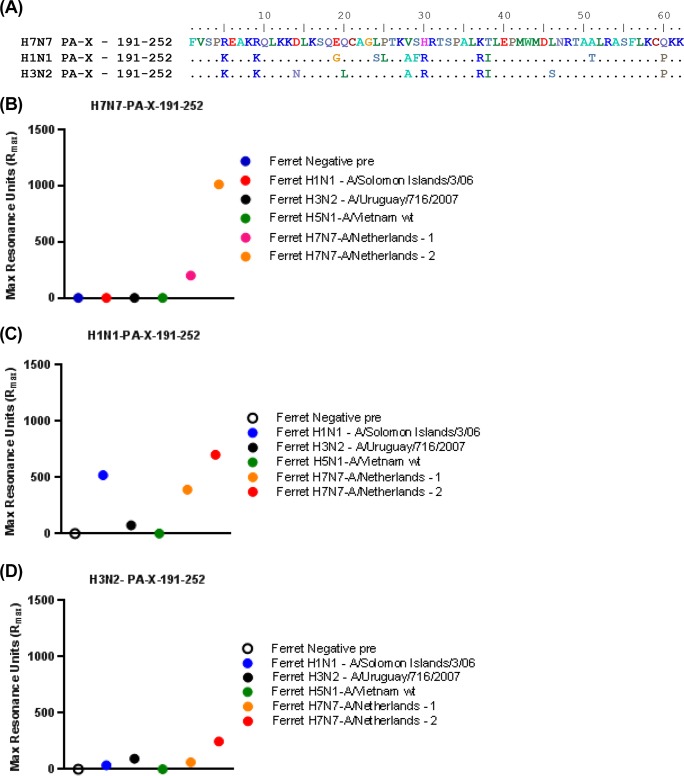

PA-X-specific antibody binding observed with sera from infected ferrets.

To further confirm the presence of PA-X binding antibodies after influenza virus infections, we measured anti-PA-X antibodies in the sera of ferrets infected with either seasonal influenza virus strains (H1N1-A/Solomon Island/3/06 and H3N2-A/Uruguay/716/07), wild-type HPAI H5N1 virus (A/Vietnam/1203/2004), or wild-type HPAI H7N7 A/Netherlands/219/03 virus (two ferrets). The sequences of the PA-X peptides (residues 191 to 252) derived from H7N7, H1N1, and H3N2 are shown in Fig. 6A (and a complete alignment of PA-X sequences is shown in Fig. 5). As shown in Fig. 6B, only the two serum samples from ferrets infected with H7N7 A/Netherlands/219/03 reacted with the H7 PA-X peptide (residues 191 to 252) by SPR. The same two serum samples from H7N7-infected ferrets also reacted with H1N1 PA-X (Fig. 6C) and reacted weakly to the H3N2 PA-X C-terminal peptide (Fig. 6D). Importantly, the serum samples from ferrets infected with H1N1 (A/Solomon Island/3/06) reacted only with H1N1 PA-X and not with H7N7 PA-X (Fig. 6B and C). In contrast, the serum samples from ferrets infected with H3N2 (A/Uruguay/716/2007) reacted weakly only with PA-X peptides from the seasonal strains (Fig. 6C and D). Serum obtained from ferrets following H5N1 (A/Vietnam/1203/2004) infection did not react with the PA-X peptides from H7N7 or the seasonal strains (Fig. 6B to D). These data suggest that PA-X antibodies are generated to different degrees during ferret infection with wild-type influenza virus strains, suggesting variable timing or levels of PA-X expression and/or stability of the PA-X protein following virus infection.

FIG 6.

Reactivity of sera from ferrets infected with seasonal or avian influenza viruses against PA-X peptides determined by using SPR. Preinfection ferret serum and sera from ferrets infected with wild-type influenza virus strains (H1N1 A/Solomon Islands/3/06, H3N2 A/Uruguay/716/2007, H5N1 A/Vietnam/1203/2004, and H7N7 A/Netherlands/219/03) were analyzed with PA-X peptides (A) derived from H7N7 (B), H1N1 (C), and H3N2 (D) by SPR. wt, wild type.

Therefore, the high anti-PA-X reactivity in the sera of H7N7-exposed individuals provided the first evidence that PA-X is expressed following infection with HPAI H7N7 virus and is recognized by the immune system, leading to the production of high-titer antibodies in infected individuals.

DISCUSSION

HPAI viruses of the H7 subtype are still causing widespread infections in bird populations. In the past 15 years, multiple outbreaks of avian-origin HPAI H7N7 viruses and adaptation of LPAI H7N7 viruses to HPAI H7N7 viruses in poultry in Europe and H7N9 viruses in southeast China, with a few cases of possible human-to-human transmission, have been reported (7, 21–23). In the absence of preexisting immunity against these emerging strains, it is feared that further adaptation of HPAI H7 viruses to allow human-to-human transmission will result in a global pandemic. In The Netherlands, a highly pathogenic H7N7 virus caused disease in poultry and infected at least 89 humans (one death), with evidence of limited person-to-person transmission in 2003 (21). Several key mutations were identified, including a polybasic cleavage site in HA and the virulence-associated PB2 E627K substitution, leading to speculation that this virus can adapt for sustained transmission in mammals (22, 24). Therefore, for an in-depth understanding of the humoral immune response following natural H7N7 infection, we used GFPDL analyses to identify all linear and conformational epitopes recognized by postinfection antibodies and real-time kinetics to quantify antibody binding, Ig isotype, and antibody affinity for different HA antigenic domains in the H7N7 virus. The epitope repertoires in HA were significantly different between individuals with no HI titers (<1:10) and individuals with positive HI titers (1:160). A shift from binding of epitopes in the C terminus of HA1 to binding of large epitopes spanning the RBD was seen. These large peptides are expected to express conformational epitopes targeted by neutralizing antibodies, as previously demonstrated for sera obtained following H5N1 infection (13). Interestingly, we recently observed a similar shift in epitope patterns between H7N7 live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV)-vaccinated individuals (no HI titers; antibody binding to the C terminus of HA1) and the same individuals after a boost with an H7-inactivated subunit vaccine (good HI titers; strong binding to the RBD) (12). Most of the C-terminal epitopes are predicted to be buried in the HA structure (25). Importantly, antibody binding to the oligomeric H7-HA1 domain (but not HA2) determined by SPR correlated strongly with the observed HI titers in the individual sera obtained following H7N7 exposure.

N7-NA binding was more limited among H7N7-exposed individuals (40%) and did not correlate with HA binding or HI titers. The NA phage clones included functional epitopes close to the sialic acid binding site, as was observed for antibodies against H5N1 NA in sera obtained following H5N1 infection (13). It remains to be determined if anti-NA antibodies play a key role in the clearance of HPAI virus infections or protection against subsequent exposures.

Antibody binding to H7N7 HA1 and NA confirmed the H7N7 exposure status, including subjects with no measurable HI or neutralization titers (9). It underpins the previous suggestion that humans undergo more subclinical infections with avian influenza viruses resulting from poultry-to-human transmission than is generally thought (9).

The most important finding in our antigenic fingerprinting of H7N7 was the identification of antibody epitopes unique to PA-X. This protein was identified in 2012 as a product of programmed ribosomal frameshifting leading to an N-terminal sequence that is shared with the PA protein and a C-terminal sequence that is unique to the PA-X protein (15). PA-X plays an important role in modulating viral growth (16, 17) and suppression of the host antiviral immune responses (26), especially at later stages of infection (27). Importantly, high evolutionary conservation of the PA-X reading frame in segment 3 of type A influenza viruses was demonstrated, suggesting that PA-X is important for influenza A virus biology (28). However, to date, there has been no direct demonstration of PA-X expression during natural influenza infections by HPAI viruses or seasonal influenza in humans. The presence of high-titer PA-X binding antibodies to the unique C-terminal PA-X sequence in the majority of serum samples from of H7N7-exposed persons evaluated in this study provides the first evidence for in vivo expression of PA-X and its recognition by the immune system during human influenza A virus infection. The samples did not react appreciably with PA-X peptides derived from seasonal H1N1 and H3N2 strains. Several control panels from subjects with no known H7N7 exposure (but with HI titers against multiple seasonal strains) showed low or no reactivity with the H7N7 PA-X peptide sequence (Fig. 4 and data not shown) (12).

The specificity of binding to H7N7 PA-X was further confirmed by using postinfection sera from naive ferrets that were infected with seasonal influenza virus strains, avian H5N1 virus, or HPAI H7N7 virus. The only significant binding to H7N7 PA-X was observed with sera from wild-type HPAI H7N7 virus-infected ferrets. Serum samples from H1N1- and H3N2-infected ferrets demonstrated weak binding to the respective homologous PA-X proteins, suggesting that some seasonal strains also expressed PA-X to elicit an antibody response in vivo. The role of PA-X in the pathogenesis of different strains will require further investigations.

In summary, the use of GFPDLs allowed unbiased, comprehensive mapping of the epitope repertoire of polyclonal serum epitopes in membrane and internal genes and led to new insights into the repertoire of anti-influenza virus antibodies following H7N7 exposure. Furthermore, GFPDL analyses can identify antibody responses against novel viral proteins, such as PA-X, that contribute to pathogenesis by modifying the host response to the infecting influenza virus. Finally, conserved epitopes recognized by serum/plasma from infected individuals may be useful for monitoring outbreaks of avian influenza. This knowledge can help inform in the development and selection of the most effective countermeasures for prophylactic as well as therapeutic treatments of HPAI H7N7 avian influenza viruses.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Maryna Eichelbereger and Zhiping Ye for their insightful review of the manuscript. We thank principal investigators Marion Koopmans, Arnold Bosman, Mirna Robert-Du Ry van Beest Holle, and Yonne Mulder of the Dutch 2003 H7N7 outbreak investigation team for collecting and making available the sera and associated patient and epidemiological data used in this study. We thank Ron Fouchier, Erasmus Medical Center, The Netherlands, for providing the ferret sera obtained following H7N7 infection.

This work was supported by FDA MCM funds.

Funding Statement

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Morens DM, Taubenberger JK. 2015. How low is the risk of influenza A(H5N1) infection? J Infect Dis 211:1364–1366. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee DH, Torchetti MK, Winker K, Ip HS, Song CS, Swayne DE. 2015. Intercontinental spread of Asian-origin H5N8 to North America through Beringia by migratory birds. J Virol 89:6521–6524. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00728-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gambotto A, Barratt-Boyes SM, de Jong MD, Neumann G, Kawaoka Y. 2008. Human infection with highly pathogenic H5N1 influenza virus. Lancet 371:1464–1475. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60627-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koopmans M, Wilbrink B, Conyn M, Natrop G, van der Nat H, Vennema H, Meijer A, van Steenbergen J, Fouchier R, Osterhaus A, Bosman A. 2004. Transmission of H7N7 avian influenza A virus to human beings during a large outbreak in commercial poultry farms in The Netherlands. Lancet 363:587–593. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15589-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fouchier RA, Schneeberger PM, Rozendaal FW, Broekman JM, Kemink SA, Munster V, Kuiken T, Rimmelzwaan GF, Schutten M, Van Doornum GJ, Koch G, Bosman A, Koopmans M, Osterhaus AD. 2004. Avian influenza A virus (H7N7) associated with human conjunctivitis and a fatal case of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:1356–1361. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308352100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bos ME, Van Boven M, Nielen M, Bouma A, Elbers AR, Nodelijk G, Koch G, Stegeman A, De Jong MC. 2007. Estimating the day of highly pathogenic avian influenza (H7N7) virus introduction into a poultry flock based on mortality data. Vet Res 38:493–504. doi: 10.1051/vetres:2007008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gao R, Cao B, Hu Y, Feng Z, Wang D, Hu W, Chen J, Jie Z, Qiu H, Xu K, Xu X, Lu H, Zhu W, Gao Z, Xiang N, Shen Y, He Z, Gu Y, Zhang Z, Yang Y, Zhao X, Zhou L, Li X, Zou S, Zhang Y, Yang L, Guo J, Dong J, Li Q, Dong L, Zhu Y, Bai T, Wang S, Hao P, Yang W, Han J, Yu H, Li D, Gao GF, Wu G, Wang Y, Yuan Z, Shu Y. 2013. Human infection with a novel avian-origin influenza A (H7N9) virus. N Engl J Med 368:1888–1897. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1304459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vasin AV, Temkina OA, Egorov VV, Klotchenko SA, Plotnikova MA, Kiselev OI. 2014. Molecular mechanisms enhancing the proteome of influenza A viruses: an overview of recently discovered proteins. Virus Res 185:53–63. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2014.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meijer A, Bosman A, van de Kamp EE, Wilbrink B, Du Ry van Beest Holle M, Koopmans M. 2006. Measurement of antibodies to avian influenza virus A(H7N7) in humans by hemagglutination inhibition test. J Virol Methods 132:113–120. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Couch RB, Patel SM, Wade-Bowers CL, Nino D. 2012. A randomized clinical trial of an inactivated avian influenza A (H7N7) vaccine. PLoS One 7:e49704. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Babu TM, Levine M, Fitzgerald T, Luke C, Sangster MY, Jin H, Topham D, Katz J, Treanor J, Subbarao K. 2014. Live attenuated H7N7 influenza vaccine primes for a vigorous antibody response to inactivated H7N7 influenza vaccine. Vaccine 32:6798–6804. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.09.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Halliley JL, Khurana S, Krammer F, Fitzgerald T, Coyle EM, Chung KY, Baker SF, Yang H, Martinez-Sobrido L, Treanor JJ, Subbarao K, Golding H, Topham DJ, Sangster MY. 2015. High-affinity H7 head and stalk domain-specific antibody responses to an inactivated influenza H7N7 vaccine after priming with live attenuated influenza vaccine. J Infect Dis 212:1270–1278. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khurana S, Suguitan AL Jr, Rivera Y, Simmons CP, Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F, Manischewitz J, King LR, Subbarao K, Golding H. 2009. Antigenic fingerprinting of H5N1 avian influenza using convalescent sera and monoclonal antibodies reveals potential vaccine and diagnostic targets. PLoS Med 6:e1000049. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khurana S, Verma N, Yewdell JW, Hilbert AK, Castellino F, Lattanzi M, Del Giudice G, Rappuoli R, Golding H. 2011. MF59 adjuvant enhances diversity and affinity of antibody-mediated immune response to pandemic influenza vaccines. Sci Transl Med 3:85ra48. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jagger BW, Wise HM, Kash JC, Walters KA, Wills NM, Xiao YL, Dunfee RL, Schwartzman LM, Ozinsky A, Bell GL, Dalton RM, Lo A, Efstathiou S, Atkins JF, Firth AE, Taubenberger JK, Digard P. 2012. An overlapping protein-coding region in influenza A virus segment 3 modulates the host response. Science 337:199–204. doi: 10.1126/science.1222213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gao H, Sun Y, Hu J, Qi L, Wang J, Xiong X, Wang Y, He Q, Lin Y, Kong W, Seng LG, Sun H, Pu J, Chang KC, Liu X, Liu J. 2015. The contribution of PA-X to the virulence of pandemic 2009 H1N1 and highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza viruses. Sci Rep 5:8262. doi: 10.1038/srep08262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gao H, Sun H, Hu J, Qi L, Wang J, Xiong X, Wang Y, He Q, Lin Y, Kong W, Seng LG, Pu J, Chang KC, Liu X, Liu J, Sun Y. 2015. Twenty amino acids at the C-terminus of PA-X are associated with increased influenza A virus replication and pathogenicity. J Gen Virol 96:2036–2049. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.000143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oishi K, Yamayoshi S, Kawaoka Y. 2015. Mapping of a region of the PA-X protein of influenza A virus that is important for its shutoff activity. J Virol 89:8661–8665. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01132-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Verma N, Dimitrova M, Carter DM, Crevar CJ, Ross TM, Golding H, Khurana S. 2012. Influenza virus H1N1pdm09 infections in the young and old: evidence of greater antibody diversity and affinity for the hemagglutinin globular head domain (HA1 domain) in the elderly than in young adults and children. J Virol 86:5515–5522. doi: 10.1128/JVI.07085-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khurana S, Coyle EM, Verma S, King LR, Manischewitz J, Crevar CJ, Carter DM, Ross TM, Golding H. 2014. H5 N-terminal beta sheet promotes oligomerization of H7-HA1 that induces better antibody affinity maturation and enhanced protection against H7N7 and H7N9 viruses compared to inactivated influenza vaccine. Vaccine 32:6421–6432. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.09.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Du Ry van Beest Holle M, Meijer A, Koopmans M, de Jager CM. 2005. Human-to-human transmission of avian influenza A/H7N7, The Netherlands, 2003. Euro Surveill 10(12):264–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jonges M, Bataille A, Enserink R, Meijer A, Fouchier RA, Stegeman A, Koch G, Koopmans M. 2011. Comparative analysis of avian influenza virus diversity in poultry and humans during a highly pathogenic avian influenza A (H7N7) virus outbreak. J Virol 85:10598–10604. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05369-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Watanabe T, Kiso M, Fukuyama S, Nakajima N, Imai M, Yamada S, Murakami S, Yamayoshi S, Iwatsuki-Horimoto K, Sakoda Y, Takashita E, McBride R, Noda T, Hatta M, Imai H, Zhao D, Kishida N, Shirakura M, de Vries RP, Shichinohe S, Okamatsu M, Tamura T, Tomita Y, Fujimoto N, Goto K, Katsura H, Kawakami E, Ishikawa I, Watanabe S, Ito M, Sakai-Tagawa Y, Sugita Y, Uraki R, Yamaji R, Eisfeld AJ, Zhong G, Fan S, Ping J, Maher EA, Hanson A, Uchida Y, Saito T, Ozawa M, Neumann G, Kida H, Odagiri T, Paulson JC, Hasegawa H, Tashiro M, Kawaoka Y. 2013. Characterization of H7N9 influenza A viruses isolated from humans. Nature 501:551–555. doi: 10.1038/nature12392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jonges M, Welkers MR, Jeeninga RE, Meijer A, Schneeberger P, Fouchier RA, de Jong MD, Koopmans M. 2014. Emergence of the virulence-associated PB2 E627K substitution in a fatal human case of highly pathogenic avian influenza virus A(H7N7) infection as determined by Illumina ultra-deep sequencing. J Virol 88:1694–1702. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02044-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chung KY, Coyle EM, Jani D, King LR, Bhardwaj R, Fries L, Smith G, Glenn G, Golding H, Khurana S. 2015. ISCOMATRIX adjuvant promotes epitope spreading and antibody affinity maturation of influenza A H7N9 virus like particle vaccine that correlate with virus neutralization in humans. Vaccine 33:3953–3962. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hayashi T, MacDonald LA, Takimoto T. 2015. Influenza A virus protein PA-X contributes to viral growth and suppression of the host antiviral and immune responses. J Virol 89:6442–6452. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00319-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khaperskyy DA, McCormick C. 2015. Timing is everything: coordinated control of host shutoff by influenza A virus NS1 and PA-X proteins. J Virol 89:6528–6531. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00386-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shi M, Jagger BW, Wise HM, Digard P, Holmes EC, Taubenberger JK. 2012. Evolutionary conservation of the PA-X open reading frame in segment 3 of influenza A virus. J Virol 86:12411–12413. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01677-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]