Abstract

This article advances nursing research by presenting transnationalism as a framework for inquiry with contemporary immigrants. Transnationalism occurs when immigrants maintain relationships that transcend the geographical borders of their origin and host countries. Immigrants use those relationships to experience health differently within concurrent socioeconomic, political and cultural contexts than national situated populations. Nurse researchers are called upon to consider these trans-border relationships when exploring the health of contemporary immigrants. Such consideration is needed to develop relevant research designs, methods, analysis, and dissemination strategies.

Keywords: Transnationalism, Immigrants, Health, Nursing, Nursing Research

Approximately 40 million first-generation immigrants inhabit the United States (U.S.), comprising 13% of the U.S. population. 1 The significant growth of first-generation immigrants, also called foreign-born, is evidenced by the 4% increase between the years of 2009 and 2010 compared to the 1.5% increase that occurred between 2008 and 2009. 2 Immigrants have profound influences on the U.S.’s social, economic, and political welfare. 3 For example, in 2010 Peri noted that between 1990 and 2007 there was an increase in real income per worker from 6.6% to 9.9%.4 Peri reported that “immigrants expand the U.S. economy’s productive capacity, stimulate investment, and promote specialization that in the long run boosts productivity”.4, p3 Others have also highlighted the “mutual dependency between immigrants members of the host societies” including the undocumented immigrants.5 Given the impact of migration on the country’s wellbeing, it is important to continue to explore how to advance nursing research with a focus on contemporary immigrant health.

Nursing research has long focused on the interaction of socioeconomic, political, and cultural context of immigrants as a population group and as segmented groups organized into communities. 6–8 Nursing research about immigrant populations is often guided by theories such as culture care diversity and universality, 9–11 cultural competence,12 transcultural nursing, assimilationand acculturation. 13 During the decades in which these theories were developed to advance research, the focus was on how to describe the health needs of immigrants with the emphasis on their cultural values, beliefs and cultural differences. An assumption was that descriptions of those concerns could be used to promote more holistic nursing care, and/or the assumption that they have fully or are on the way to adopt the American ways of life (such conformity is said to lead to the notion of a ‘melting pot’). Another limitation is the risk of having a ‘cookbook’ to guide our understanding of immigrant health. This could further marginalize the individuals as they may not have similar approaches to care for their health as their immigrant counterparts. However, as current global and technological developments facilitate interactions, and resource exchanges both within and outside of the country, more attention is needed to understand the impacts of such interactions and resources exchanges on immigrants’ attitudes and behaviors towards health promotion and disease management. This ability permits immigrants to create individualized approaches to self-care and to no longer feel the need to assimilate. Contemporary U.S. immigrants often embrace their native language, cultural practices, and connections along with the practices in the U.S. For example, Waldinger (2007) noted that 63% of the Latino immigrants in his study were connected to their country of origin and were engaged in at least one transnational activity (including: remittance sending, weekly phone calls, and travel to native country within the past two years). 14 More importantly, many immigrants use these trans-border (local, national, international) social ties/networks as a main source of knowledge sharing, resource exchange, and decision-making. The ties have significant implications for immigrants’ health, and as such, research must be designed to address these contemporary experiences. Immigrants engaged in transnational activities no longer feel the need to forgo their native language, cultural practices and connections. Thus, research must be designed to address these contemporary experiences of immigrants which inform their health practices.

Transnationalism, as a framework, will advance a focus on cultural diversity as a hallmark value for nursing research. It will ensure that researchers consider trans-border activities and health implications. Transnationalism has been defined as: “the process by which immigrants forge and sustain multi-stranded social relations that link together their societies of origin and that of their host country”. 15, p7 Using transnationalism in nursing research among contemporary immigrants would enable an in-depth understanding of the impact of the cross-border interactions and resource exchanges on immigrants’ attitudes and behaviors towards health promotion and disease management. Having this information would allow nurse researchers to ask relevant questions that lead to effective care and understanding about immigrants’ experiences.

This purpose of this article is to describe how transnationalism can be used to guide nursing inquiry to advance the study of immigrant health. The first section of the article reviews transnationalism as an emerging framework. The second part of the article describes research guided by transnationalism. The final section of the article outlines how transnationalism, as a framework, would inform the development of nursing research. A summary concludes the article.

Transnationalism: An Emerging Framework

Since the early 1990’s, transnationalism has been adapted as a theoretical framework across various disciplines including sociology and anthropology. 16, 17 It gained momentum because it highlights the transborder-transnation phenomena, which is facilitated by the reconfigurations of globalization and its associated advancements. 17 Transnationalism provides the avenue to explore, describe, and analyze how immigrants select and juggle multiple identities simultaneously.18 An assumption of transnationalism is that persons are not bound to place, as much, as they are to space and technologies of place. Hence the term social field, which refers to the social relations and space within which exchanges (ideas, resources, networks) occur and power within those social relationships is negotiated. 19, 20

The bourgeoning of transnationalism enabled the exploration and understanding of current common interactions that are embedded in immigrants’ everyday life activities. Transnationalism has been used as a framework for describing cultural connections, social networks for labour, exchanges for business and other market related commodities, and political efforts. 17 For example, by using a transnational lens, researchers were able to describe the growth of non-profit organizations across boarders with the remittance practices of immigrants. 21 These remittance practices include any resources of materials/commodities that are exchanged across the borders of two nations. 22 The most common form of remittance is monetary, which contributes significantly to the economic standing of many receiving countries. 22 Without a transnational lens, this type of inquiry would not have been conceived.

Transnationalism also assumes cultural connectivity and reproduction, and human mobility. This assumption is based on the belief that immigrants maintain cultural ties with their home country, but also reproduce their cultural-related activities in their host country whenever necessary. 18 Additionally, transnationalism allows for analysis of active political involvement given that it assumes that some immigrants stay abreast of and influence the political-related occurrences of both their home and country of residence. 23 Thus, transnationalism encompasses individuals, their interactions (including everyday experiences, allegories, and conflicts), and their exchanges (including gifts, money, and intellectual property). These relationships and interactions occur within and across the host and home countries. Each will be described in more detail below.

Individuals

Individuals who participate in transnational ties are called transmigrants. Transmigrants create such identities because of social, political economic and labor related inequality experienced in their host country. 16, 24 Contemporary immigrants create transnational identities to cope with their new environment, build resiliency, and sustain close contact with their home state. 25, 26 This transnational identity sets transmigrants apart from those who are indigenous to the host country.

Interactions/Relationships

There have been debates on whether relationship building and maintenance across geographical boarders is a new phenomenon. 21, 27 Certainly, immigrants, centuries ago also maintained relationships with friends and family members from their native country. However, such relationships are now better facilitated with the innovative global, technological and political avenues 21 and a societal openness to the national boundary crossings that happen regularly. For example, today’s immigrants are able to board a plane and reach their home country within hours. Even without traveling, they can be alerted to news via cellphone and email communications in minutes.

Exchanges

Various forms of exchange occur. They include ideas, and political and social power dynamics. The most tangible exchange for transnationalism include the exchange products or goods (often in monetary form) called remittance. 25 Remittance allows immigrants to fulfill their obligations of taking care of their family members in their home country. Remittance is prominent aspect of transmigrant life and transnationlism identity creation. 25

Transnationalism and Health: The Need for Consideration in Nursing

A small and growing number of scholars are using transnationalism within the field of nursing. 28–30 Gastaldo and colleagues 26 explored transnational health promotion among immigrant women living in Canada. They found that immigrant women used information within their social fields in their host country as well as from their home state to maintain and promote their physical and psychological health. 28 Transnationalism with specific emphasis on the women’s accounts for their experience with the “here and there” guided the study. Analysis of the data focused on three major elements 1) expecting to live in a better place; 2) giving and receiving care across borders, and 3) women as transnational health promoters. The findings revealed new immigrant women’s perspectives on the social inequalities they experienced as they negotiated role identity in their host country.

A study by another nurse researcher explored hypertension management among a group of Haitian immigrants using the transnationalism framework.31 The study findings indicated that transmigrant life was rooted in everyday actions of the participants, including their health promotion and disease management activities.31 Guided by this framework, during the interviews with the participants, the researcher acquired information about participants’ behaviors and activities, and access to resources both within their home country of Haiti, and their resident country of United States. Transnationalism guided the development of the study inclusion and exclusion criteria, the interview guide, the Photovoice guide and the analysis.

The disciplines of public health and psychology have paid attention to the relationship between transnationalism and immigrants’ health. For example, Murphy and Mahalingam (2004) developed an empirical measure to explore the nature and frequency of transnational practices. The Transnationalism Scale contained 21 items (each measured on a 5 point Likert scale with zero indicating low and 5 indicating high transnational activities) which were grouped into four domains which included family ties, cultural ties, economic ties, and political ties. They examined the reliability of the scale (sample size: N=137) that had a Cronbach’s alpha (α) of 0.87. They found a positive relationship between transnationalism and perceived social support (r=0.23, p≤0.01).32 Transnationalism was also positively correlated with life satisfaction (r=0.20, p≤0.05) and depression (r=0.20, p≤0.05). Their findings indicated that transnationalism has important implication for immigrants’ psychological wellbeing and spans their lives across all levels, including individual, family, and social.32 This scale is the only measure to focus on transnationalism in the context of health.

In addition, Messias’29, 30 studies with Brazilian immigrants found that the participants were involved in pre-emigration as well as transnational resources and health practices in order to maintain their health. For example, the Brazilian women often requested remedies and medications from their home state to manage their illness in the U. S. 29 Messias used transnationalism to guide the research design specifically focused on the research aims, data collection and analysis.

Researchers are clearly using transnationalism as a research framework to understand the health of contemporary immigrants. However much remains to be done as this framework has not been fully disseminated or used in health fields such as nursing. Without consideration for study participants’ transnational identities, nurse researchers risk bypassing some important aspects of immigrants’ health and disease experiences. Nurse researchers who aim to address the health of contemporary immigrants would benefit from the transnationalism framework because it would provide a new way of thinking about how to design research studies while staying abreast the movements of globalization, communication, transportation, and technological advancements, impacting science and immigrants’ health.

Transnationalism Informing Nursing Research

Transnationalism offers a novel theoretical lens to conduct nursing research about contemporary immigrants. Application of such a framework encompasses the consideration for cultural and social contexts both within and outside of the boarders of the immigrants’ country of residence. Nurse researchers who aim to address the health of contemporary immigrants would benefit from the transnationalism framework because it would provide a new way of thinking about how to design research studies. Below is an illustration regarding how a research study design conceptualization may change using a transnationalism framework (Table 1).

Table 1.

Examples of Current and Proposed Nursing Research Methods Guided by Transnationalism

| Current Nursing Research Methods | Proposed Nursing Research Method Guided by Transnationalism | |

|---|---|---|

| Study design | Various designs: i.e. cross-sectional, longitudinal and experimental study designs to explore health within one country (one geographical context). | Various designs: i.e. 1) Cross-sectional design to investigate how living across two nations relates to patterns of health and disease 2) Longitudinal design to clarify how immigrants are developing their transnational identities and how those identities inform health patterns over time |

| Participants |

|

|

| Data Collection |

|

|

| Data Analysis |

|

|

| Implications |

|

|

Study design

Using transnationalism as a framework will promote the use of diverse cross-sectional, longitudinal and experimental study designs. Researchers may investigate how living across two nations relates to patterns of health and disease using a cross-sectional design. Longitudinal design would help clarify how immigrants are developing their transnational identities and how those identities inform health patterns over time. Researchers can also study immigrants who ascribe to transnationalism and those who do not to determine if transnationalism is a risk or protective factor for individual or family level health indicators. Consideration for transnationalism is of upmost importance when conducting research with immigrant populations.

In addition, transnationalism can enhance qualitative, quantitative, mixed methods research and intervention studies. For example, in qualitative studies, interview questions would inquire about transnational practices. Given that the application of transnationalism in nursing and health research in general is at its infancy, transnationalism would be a good fit with grounded theory to relay new unexplored messages/approaches that impact and can enhance immigrants’ health. The Transnationalism Scale is a first step at quantitatively exploring transnational practices among immigrants. More studies need to be conducted to explore the reliability and validity of this scale across different contemporary immigrants of various origins. Transnationalism could also guide intervention research. For example in a clinical trial where participants are to take a specific drug with the control group being on a placebo, it is important for the researcher to explore how the individuals’ cultural practices would impact full participation and adherence to the research protocols and activities.

Research Sample Considerations

Transnationalism will inspire consideration for different inclusion and exclusions criteria with research samples. Individuals who have been in the US for much longer (i.e. longer than 15 years) may have fewer connections with their home countries. Others may not be involved in transnational practices and may have assimilated to American culture. Therefore, if the research study is specifically targeting transmigrants, it behooves the nurse researcher to specify in all aspects, including the recruitment flyers that interested individuals need to be involved in at least one transnational practice. The use of the Transnationalism Scale developed by Murphy and Colleague may also be another approach to explore involvement in transnational practices. In addition, participants may travel between countries therefore retention in a research study may become an issue. To address this issue, clarification for travel plans are to be explored during recruitment and consenting. Retention may be a particular issue in longitudinal studies.

Data Collection Instruments

For quantitative data collection, Murphy and colleague32 set the example of how transnationalism can guide demographic data collection. Using a transnationalism scale, they were able to capture participants’ life experiences both within and across their home and host countries. The characteristics of the sample thus differ. When describing study participants, it does not suffice to just report common aspects such as age, gender, education, marital status and income. To put everything in context, it is important to also capture remittance practices, report length of stay, years of migration, age at time of migration as well as transborder-activities.

For qualitative data collection, nurse researchers can explore the participants’ migration experiences. For example, many individuals immigrate to the U.S. because of home country socioeconomic and political influences. Consequently, many immigrants may choose to stay in the U.S. despite the encountered difficulties to help friends and family members back home. When a researcher, for example, is exploring hypertension management among an immigrant group, inquiring about their transnational experiences related to hypertension management invites opportunity for knowledge sharing. Examples of the research interview questions can include: “What other strategies do you use to manage your disease? What roles do your network and resources in your country of origin and your current country of residence play in the management of your disease?” These questions will help understand the context of the immigrants’ life and the how and why they are experiencing their disease a certain way. The researcher will need to capture participants’ experiences in both countries that may relate to health. This will enable an exploration of whether there is a balance between feeling of inequality in the home county and feeling of comfort in the host county. Thus survey and analysis sensitivity are needed.

Data Analysis

During data analysis, nurse researchers can involve study participants to determine what matters most as data in the home country and what matters most as data in the host country. When exploring health beliefs, and health practices of contemporary immigrants, researchers must reflect on their consideration of transnational identities. With transnationalism, research will account for the historical, sociopolitical and economic influences of individuals’ dual lives.

Data analysis may particularly be a challenge given that the nurse researcher will need to pay close attention to the duality of context. That is, participants’ lives are anchored in more than one context. This requires thinking about compliments and contradictions within lived experiences, not just either/or, dichotomies. In addition to the local contextual factors influencing the transmigrants’ life (i.e., current workplace, local policies, and access to resources), exploration of transborder context is also important. Transnational context may include immigration policies, currency exchange, remittance practices, and travels between the two countries. Transnational context may influence study participants’ health beliefs and approaches to disease management. Participants may experience conflicts between the western biomedical practices in their host countries and cultural beliefs and approaches that they practice within their transnational space.

Dissemination

Given the interplay between countries of birth and residency for contemporary immigrants, research findings can have local, national, and international implications. Thus careful consideration must be taken with respect to the audience for study finding dissemination. Conference and journal publications must consider the transborder audience and politics. Study findings-for example remittance leading to stress and financial strain among immigrants33 and potentially promoting the social and health status of those living on the home country- have important implications for local and international policies and require further explorations.

Implications

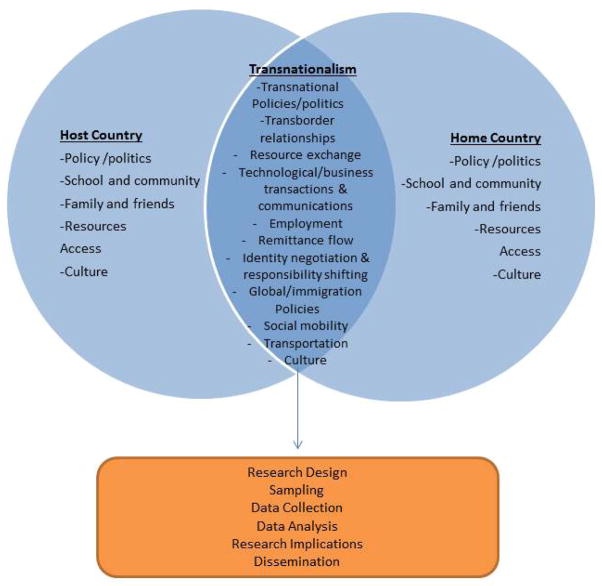

A research study among contemporary immigrants guided by transnationalism as a framework can have several implications. First, in all aspects of the study, including the background and theoretical underpinnings, as nurse researchers integrate transnationalism in their research they will be able to address the issue of situatedness. That is, contemporary immigrants’ experiences with health and disease self-management will not be examined in-situ.34 As such, exploration of immigrants’ health promotion and disease management experiences will go beyond the boundaries of the local issues and politics they face within their host countries (i.e., discrimination, access to resources, insurance coverage). Transnationalism behooves nurse researchers to tap into the real-life experiences of immigrants which also include additional stressors/factors impacting their health such as gender issues (i.e., gender-identify negotiation for immigrant women);35, 36 business transactions and policies (i.e., immigration policies);21, 37 social status (i.e., social mobility, downgrading);35 psychological issues (i.e., social support);34 employment, culture shock and adaptation (see figure 1).34 These experiences/issues differ in their entirety between contemporary immigrants and the natives of their host country, including the marginalized, United States home country residents.38 Nurse researchers can use transnationalism as an approach to explore and interpret the complex health and social experiences of contemporary immigrant among study participants. Such level of exploration will reflect health equity research design and will promote change at the core of health disparities specific to contemporary immigrant populations.

Figure 1.

Transnationalism & Research Among Contemporary Immigrants

Conclusion

Transnationalism is driving current understandings about the socioeconomic and political contexts anchoring the beliefs and behaviors of contemporary immigrants. Transnationalism is a useful framework to advance nursing inquiry with contemporary immigrants. Certainly more studies are needed to support the research process described in this paper about the application of transnationalism in nursing research. However this is more the reason why we are behooved to conduct more studies and explore the effectiveness of transnationalism in health exploration among contemporary immigrants. The two studies conducted by nurse researchers 33, 34 described in this article are a step towards such application. What is evident is that transnationalism provides an avenue for nurse researchers to go beyond participants’ current residence location, when considering context, access, and health outcomes.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: This article is the original work of the authors who have no conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Contributor Information

Marie-Anne S. Rosemberg, Email: sanon@umich.edu, Research Fellow, School of Nursing, University of Michigan, 400 North Ingalls, Room 3356, Ann Arbor, MI, 48109, Tel: (734)-647-0146.

Doris M. Boutain, Email: dboutain@u.washington.edu, Associate Professor, School of Nursing, University of Washington, Box 357263, Seattle, WA 98195-8732.

Selina A. Mohammed, Email: selinam@uw.edu, Associate Professor, School of Nursing and Health Studies, University of Washington Bothell, 18115 Campus Way NE, Bothell, WA, 98011-8246.

References

- 1.United States Census Bureau. Selected social characteristics in the United States: 2007–2011 American Community Survey (ACS) 5-year estimate. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Batalova J, Lee A. Frequently requested statistics on immigrants and immigration in the United States. Available at: http://www.migrationinformation.org/usfocus/display.cfm?ID=886.

- 3.Camarota SA. Immigrants in the United States, 2010: A profile of America’s foreign born population. Center for Immigration Studies; Available at: http://www.cis.org/2012-profile-of-americas-foreign-born-population. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peri G. The Effect of Immigrants on US Employment and Productivity. FRBSF Economic Letter. 2010;26:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Esses VM, Brochu PM, Dickson KR. Economic costs, economic benefits, and attitudes toward immigrants and immigration. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy. 2012;12(1):133–137. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leininger M. Transcultural nursing presents an exciting challenge. The American Nurse. 1976;5(5):6–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leininger M. Transcultural nursing research to transform nursing education and practice: 40 years. Image. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 1997;29:341–347. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1997.tb01053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fawcett J. The Nurse Theorists: 21st-Century Updates—Jean Watson. Nursing Science Quarterly. 2002;15(3):214–219. doi: 10.1177/08918402015003007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leininger M. Transcultural nursing presents exciting challenge. The American Nurse. 1975;7(5):4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leininger M. Culture care theory: A major contribution to advance transcultural nursing knowledge and practices. Journal of transcultural nursing. 2002;13(3):189–192. doi: 10.1177/10459602013003005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leininger MM. Leininger’s theory of nursing: Cultural care diversity and universality. Nursing Science Quarterly. 1988;1(4):152–160. doi: 10.1177/089431848800100408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campinha-Bacote J. The process of cultural competence in the delivery of health care services: A model of care. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2002;13(3):181–184. doi: 10.1177/10459602013003003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berry J. Conceptual approaches to acculturation. In: Chun KM, Organista PB, Marin G, editors. Acculturation: Advances in theory, measurement, and applied research. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2002. pp. 17–37. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Waldinger R, Center PH. Between Here and There: How Attached Are Latino Immigrants to Their Native Country? Pew Hispanic Center; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Basch L, Glick-Schiller N, Szanton-Blanck C. Nations Unbound: Transnational projects, postcolonial predicaments and deterritorialized Nation-States. Amsterdam: Gordon and Breach Publishers; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Basch L, Schiller NG, Blanc CS. Nations unbound: Transnational projects. New York, NY: Gordon and Breach Science Publishers; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foner N. What’s new about transnationalism?: New York immigrants today and at the turn of the century. Diaspora: A Journal of Transnational Studies. 1997;6(3):355–375. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vertovec S. Transnationalism and identity. Journal of Ethnic and Migration studies. 2001;27(4):573–582. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levitt P, Schiller NG. Conceptualizing simultaneity: A transnational social field perspective on society. International Migration Review. 2004;38(3):1002–1039. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Faist T. Transnationalization in international migration: implications for the study of citizenship and culture. Ethnic and racial studies. 2000;23(2):189–222. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Portes A. Introduction: the debates and significance of immigrant transnationalism. Global networks. 2001;1(3):181–194. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Orozco M, Lowell BL, Bump M, Fedewa R. Transnational engagement, remittances and their relationship to development in Latin America and the Caribbean. Institute for the Study of International Migration; Georgetown: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Itzigsohn J. Immigration and the boundaries of citizenship: the institutions of immigrants’ political transnationalism. International Migration Review. 2000:1126–1154. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Charles C. Transnationalism in the Construct of Haitian Migrants’ Racial Categories of Identity in New York Citya. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1992;645(1):101–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb33488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vertovec S. Trends and impacts of migrant transnationalism. Oxford: Center on migration policy and society; 2004. p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Waldinger R, Fitzgerald D. Transnationalism in question. American Journal of Sociology. 2004;109(5):1177–1195. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Foner N. What’s new about transnationalism?: New York immigrants today and at the turn of the century. Diaspora: A Journal of Transnational Studies. 2011;6(3):355–375. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gastaldo D, Gooden A, Massaquoi N. Transnational health promotion: Social well-being accross borders and immigratn women’s subjectivities. In: Asgharzadeh AO, K, editors. Diasporic Ruptures: Transnationalism, globalization and identity discourses. Toronto: Unviersity of Toronto Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Messias DKH. Transnational health resources, practices, and perspectives: Brazilian immigrant women’s narratives. Journal of Immigrant Health. 2002;4(4):183–200. doi: 10.1023/A:1020154402366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Messias DKH. Transnational perspectives on women’s domestic work: Experiences of Brazilian immigrants in the United States. Women & Health. 2001;33(1–2):1–20. doi: 10.1300/J013v33n01_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sanon M-A, Mohammed SA, McCullagh MC. Definition and Management of Hypertension among Haitian Immigrants: A Qualitative Study. Journal of health care for the poor and underserved. 2014;25(3):1067. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2014.0147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murphy EJ, Mahalingam R. Transnational ties and mental health of Caribbean immigrants. Journal of Immigrant Health. 2004;6(4):167–178. doi: 10.1023/B:JOIH.0000045254.71331.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sanon M-A, Spigner C, McCullagh MC. Transnationalism and Hypertension Self-Management Among Haitian Immigrants. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2014 doi: 10.1177/1043659614543476. 1043659614543476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gastaldo D, Gooden A, Massaquoi N. Transnational health promotion: Social well-being across borders and immigrant women’s subjectivities. Wagadu. 2005;2:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Salih R. Moroccan migrant women: transnationalism, nation-states and gender. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. 2001;27(4):655–671. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zontini E. Immigrant women in Barcelona: Coping with the consequences of transnational lives. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. 2004;30(6):1113–1144. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ley D. Does transnationalism trump immigrant integration? Evidence from Canada’s links with East Asia. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. 2013;39(6):921–938. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Erdal MB, Oeppen C. Migrant balancing acts: understanding the interactions between integration and transnationalism. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. 2013;39(6):867–884. [Google Scholar]