Abstract

Objective

Although recent studies have shown that 30-day readmissions following sepsis are common, the overall fiscal impact of these rehospitalizations and their variability between hospitals relative to other high-risk conditions, such as congestive heart failure (CHF) and acute myocardial infarction (AMI), are unknown. The objectives of this study were to characterize the frequency, cost, patient-level risk factors and hospital-level variation in 30-day readmissions following sepsis compared to CHF and AMI.

Design

A retrospective cohort analysis of hospitalizations from 2009 to 2011.

Setting

All acute-care, non-federal hospitals in California

Patients

Hospitalizations for sepsis (N=240,198), CHF (N=193,153), and AMI (N=105,684) identified by administrative discharge codes.

Measurements and Main Results

The primary outcomes were the frequency and cost of all-cause 30-day readmissions following hospitalization for sepsis compared to CHF and AMI. Variability in predicted readmission rates between hospitals was calculated using mixed effects logistic regression analysis. The all-cause 30-day readmission rates were 20.4%, 23.6%, and 17.7% for sepsis, CHF and AMI, respectively. The estimated annual costs of 30-day readmissions in the state of California during the study period were $500 million/year for sepsis, $229 million/year for CHF, and $142 million/year for AMI. The risk and reliability-adjusted readmission rates across hospitals ranged from 11.0% to 39.8% (median 19.9%, IQR 16.1–26.0%) for sepsis, 11.3% to 38.4% (median 22.9%, IQR 19.2–26.6%) for CHF, and 3.6% to 40.8% (median 17.0%, IQR 12.2–20.0%) for AMI. Patient-level factors associated with higher odds of 30-day readmission following sepsis included younger age, male gender, Black or Native-American race, a higher burden of medical co-morbidities, urban residence, and lower income.

Conclusion

Sepsis is a leading contributor to excess healthcare costs due to hospital readmissions. Interventions at clinical and policy levels should prioritize identifying effective strategies to reduce sepsis readmissions.

Keywords: sepsis, hospital readmissions, costs, health services, quality of healthcare, delivery of healthcare

INTRODUCTION

Decreasing rates of hospital readmissions has emerged as an important approach to improving the quality and efficiency of healthcare delivery.[1, 2] The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) began publicly reporting 30-day hospital readmission rates for common conditions including acute myocardial infarction (AMI), congestive heart failure (CHF) and community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) as an incentive for healthcare organizations to improve care delivery and lower costs.[1, 3] Furthermore, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act has brought 30-day readmissions to the forefront of healthcare priorities by requiring CMS to reduce payments to hospitals that have excess readmissions for these diagnoses.

In the United States there are approximately 700,000 cases of sepsis annually, resulting in an economic burden of approximately $15–24 billion.[4–8] Although recent studies have shown that 30-day readmissions following sepsis are common, the overall fiscal impact of these rehospitalizations, the risk factors for readmissions, and their variability between hospitals relative to other high-risk conditions are unknown.[9–12] Understanding these factors is critical to assessing whether sepsis readmissions are mutable, and whether interventions that reduce these rehospitalizations will substantively improve the global readmissions problem. Thus, the goals of this study were to 1) estimate the frequency and cost of 30-day readmissions following hospitalization for sepsis compared to CHF and AMI, 2) examine the variability of risk-adjusted 30-day readmission rates between hospitals, and 3) identify the patient-level risk factors which can inform the development of future interventions that reduce readmissions after sepsis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data Source

Data for this study were obtained from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) State Inpatient Database (SID) maintained by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ).[13] We focused analyses on data from California, as it is a large, ethnically-diverse state with readmissions data reported annually in the SID. Discharge and visit records from the SID include de-identified information on patient demographics, expected payer, ZIP code of residence, diagnosis and procedure codes, admission source, disposition after hospitalization, length of stay, total charge for hospitalization, and hospital identification code. Cost of each hospitalization was calculated from total charges using hospital-specific cost-to-charge ratios provided by HCUP. [13][14] The hospital-level cost-to-charge ratios were merged with the SID database by the hospital identification code, and the total costs were estimated by multiplying the total charges with the cost-to-charge ratio for each calendar year. The costs were adjusted to 2011 using the medical component of the Consumer Price Index.[15] Hospital characteristics were obtained by linking the SID database with California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development (OSHPD) Patient Discharge Pivot Database by hospital identification codes (‘DHOSPID’ in the SID to ‘oshpd_id’ in the OSHPD Patient Discharge Pivot Database) for each calendar year.[16]

Study Design

This was a retrospective cohort study of adult patients (age > 18) who were hospitalized in California for sepsis, CHF, and AMI during 2009 to 2011. Hospitalizations for sepsis were identified based on the presence of a compatible International Classification of Diseases, ninth revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9 CM) code as the principal diagnosis for hospital admission. The ICD-9 CM codes that were used for sepsis were based on the Martin implementation: 038 (septicemia), 020.0 (septicemic), 790.7 (bacteremia), 117.9 (disseminated fungal infection), 112.5 (disseminated candida infection), and 112.81 (disseminated fungal endocarditis). These codes have been previously used in population-based studies of sepsis, and the 038 code was found to have a positive predictive value of 97.7% and negative predictive value of 80.0% using the clinical definition of sepsis as the gold standard.[7, 17] In our study population, 98.5% of the sepsis hospitalizations were identified based on the 038 code. For sensitivity analysis, we also examined the frequency, cost, and risk factors of 30-day readmissions in 2011 using the Angus implementation to identify hospitalizations for severe sepsis.[4] The ICD-9 CM codes used to define the cohorts with congestive heart failure (402.01, 402.11, 402.91, 404.01, 404.03, 404.11, 404.13, 404.91, 404.93, 428.XX) and acute myocardial infarction (410.XX) were consistent with the definitions used in the CMS reporting program and in previous studies.[18–20]

Patients were excluded from the analysis if they were hospitalized at a non-acute care facility, younger than 18 years, out-of-state residents, or missing information on length of stay or the unique encrypted patient identifier used in the HCUP database (VisitLink). Hospitals that reported less than 10 annual hospitalizations for sepsis, CHF, or AMI were excluded for analyses of each condition. For calculating index admissions for 30-day readmissions, hospitalizations occurring in December of each year were excluded to allow a 30-day window for rehospitalization. Similarly, for calculation of 90-day readmission rates, hospitalization occurring in October, November, and December were excluded. The study was approved as an exempt protocol by the institutional review board at Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute.

Statistical Analysis

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the all-cause 30-day readmission rate following hospitalization for sepsis. The unit of analysis was individual hospitalizations. The 30-day readmission rate for sepsis was calculated by dividing the number of hospitalizations with at least one subsequent hospital stay within 30 days of an index hospitalization by the total number of index hospitalizations for sepsis.[21] Index hospitalizations were defined as all hospital admissions with a primary diagnosis of sepsis that did not result in transfer to another acute care hospital or patient death. Hospitalizations resulting in a transfer to another hospital were excluded because in the SID database if a patient is admitted to one hospital and transferred to another facility, two hospitalization records are created (one for each hospital). We felt that despite being hospitalized at two separate facilities, this should be analyzed as one hospitalization with 30-day readmissions being ascribed to the discharging hospital. With the exception of the first hospitalization in each calendar year, hospitalizations were eligible to be both an index hospitalization for future readmissions and a readmission for a prior hospitalization. Similar approaches were used to calculate the 30-day readmission rates for CHF and AMI. We chose to compare sepsis to CHF and AMI because these, along with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), are among the high-risk conditions that are tracked in the CMS Readmissions Reduction Program. We did not compare sepsis to CAP in our study because these conditions are not mutually exclusive, and coding patterns for sepsis and CAP are likely to vary between hospitals and over time.[22] Length of stay, hospital mortality, and costs of hospitalization were calculated for all hospitalizations, index hospitalizations, and 30-day readmissions for sepsis, CHF, and AMI. Because length of stay and costs of hospitalization were not normally distributed, both medians and means are presented.

Causes of Readmissions

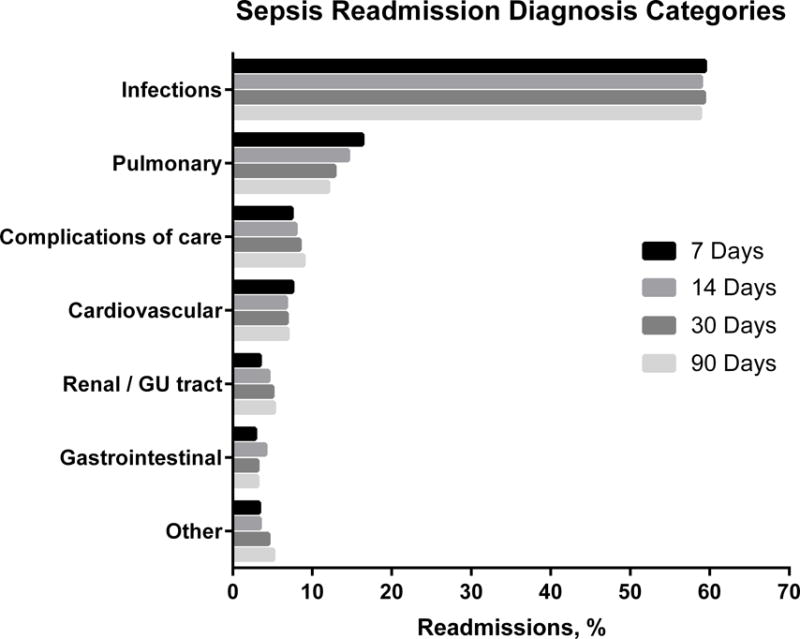

The most common diagnoses on readmission following sepsis were identified based on the primary Clinical Classification Software (CCS) code for each rehospitalization which collapses ICD-9 CM codes into clinically meaningful categories.[23] The cumulative frequencies of the 20 most common CCS primary diagnosis codes for 7, 14, 30, and 90-day readmissions were examined for longitudinal changes in causes of readmission. We further consolidated the CCS diagnoses into seven clinical categories (infection, pulmonary, complications of care, cardiovascular, renal/genitourinary, gastrointestinal) to facilitate more meaningful data interpretation. The CCS diagnoses included in each clinical category are provided in the Online Supplement (Supplemental Digital Content- Table 4).

Risk Factors for 30-day readmissions

To examine the relationship between patient and hospital-level factors and 30-day readmissions following sepsis, we generated hierarchical mixed effects logistic regression models using presence of a 30-day readmission compared to no 30-day readmission as the dependent variable. The independent variables in the model were hospital-associated factors (number of beds, teaching status, proportion of minority patients, hospital type), patient factors (age, ethnicity/race, gender, median income, rural or urban residence, and co-morbid conditions), and healthcare systems and hospitalization-related factors (payer status, disposition after hospitalization, and length of stay). Co-morbid conditions were identified using discharge data codes to calculate a Charlson Comorbidity Index.[24–26] The proportion of racial and ethnic minority patients seen by each hospital was estimated from the number of Black, Hispanic, Asian, and Native American patients admitted compared to total number of hospital admissions. Individual hospitals were used as random effects in the models to adjust for clustering of hospitalizations. We generated separate models for sepsis (Model 1), CHF (Model 2) and AMI (Model 3) using the same dependent and independent variables to examine whether the patient and hospital-level associations identified in the models are specific to each disease or more broadly applicable to odds of 30-day readmissions. Performance of each model was assessed by the c-statistic, calculated as the area under the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve based on fitted probabilities from the model and the true values. The data are presented as adjusted odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Adjusted odds ratios with a 95% CI excluding 1.00 were considered statistically significant.

Hospital-level Variation in 30-day Readmissions

To assess variation in readmission rates across hospitals, we created hierarchical logistic regression models to estimate the 30-day readmission rates for sepsis, CHF, and AMI in each hospital. We adjusted for case-mix by adding age and medical co-morbidities as fixed effects and used individual hospitals as the random effect. These models were different than the models used to examine the association between patient and hospital level risk factors to the odds of 30-day readmissions as they only contained age and medical co-morbidities as independent variables. We did not include patient race/ethnicity, gender, insurance status, or hospital characteristics in the models because such an adjustment may obscure factors that inappropriately influence the quality of care across hospitals. Using empirical Bayesian posterior estimates from the logistic regression model, we determined the predicted 30-day readmission rate (risk and reliability adjusted) and 95% confidence intervals at the hospital level for an average hospitalization, and displayed the ranked order of adjusted rates across hospitals in a caterpillar plot.[27–29] We used the variance component for the hospital random effect to evaluate the statistical significance of the variation in 30-day readmission rates across hospitals (P < 0.05 for statistical significance). All data analyses were performed using JMP version 11.0 and SAS for Windows version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

A total of 368,514 hospitalizations for sepsis were identified from 325 hospitals for analysis in the HCUP SID database from 2009 to 2011. After excluding hospitalizations with age < 18 (N=6,163), missing length of stay (N=55) and patient identifier number (N=17,715), out-of-state residents (N=4,368), admissions to rehabilitation or psychiatric facilities (N=2,585), discharges in December (N=34,157), transfers to another acute care hospital (N=17,174), and in-hospital death (N=58,928), there were 240,198 index hospitalizations available for analysis. The baseline characteristics of index hospitalizations for sepsis, CHF, and AMI are shown in the Online Supplement (Supplemental Digital Content- Table 1). For sepsis, median age was 72 years (IQR 57–82). The percentage of men and women were similar (47.6% versus 52.4%, respectively). Whites were the most prevalent racial/ethnic group in the study (59.1%), followed by Hispanics (20.5%), Blacks (9.3%) and Asians (9.2%). Most patients had multiple medical co-morbidities as defined by the Charlson Co-morbidity index (Supplemental Digital Content- Table 1). A similar proportion of hospitalizations for sepsis resulted in routine discharges to home (40.1%) or skilled nursing facility (39.9%). Approximately 18% of patients were discharged with home health care. The baseline characteristics of index hospitalizations for sepsis were similar between 2009, 2010, and 2011 (Supplemental Digital Content- Table 2).

There were some notable differences in baseline characteristics of index hospitalizations for sepsis versus CHF and AMI (Supplemental Digital Content- Table 1). Sepsis hospitalizations had a higher proportion of patients with dementia and malignancy as co-morbidities, resulted more frequently in hospital discharge to a skilled nursing facility (39.9% for sepsis versus 17.2% and 14.0% for CHF and AMI, respectively) and had longer length of stay (6 days, IQR 3–10 versus 3 days, IQR 2–6 for both CHF and AMI).

Readmission Rates and Costs

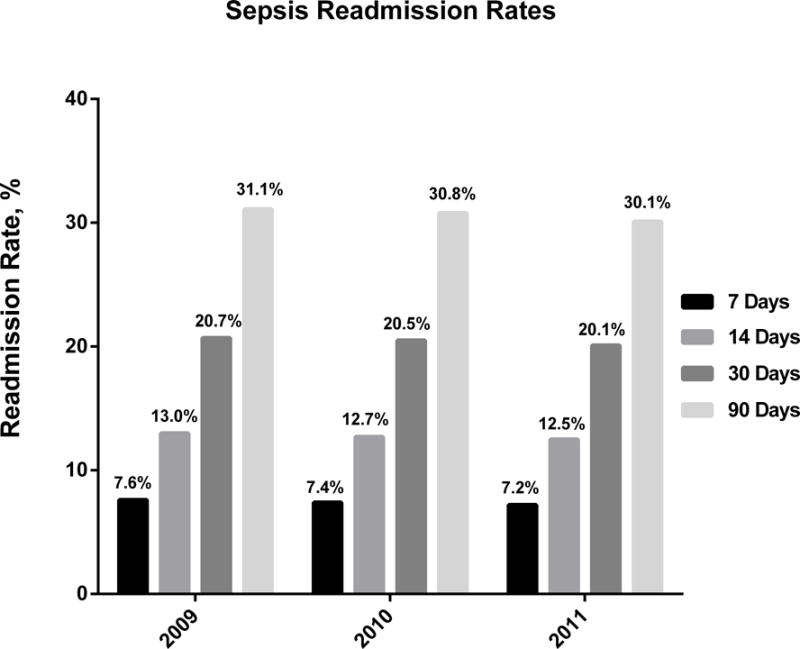

The all-cause 30-day readmission rate for sepsis during the study period was 20.4% (Table 1). The 7, 14, 30 and 90-day readmission rates for sepsis during 2009–2011 are shown in Figure 1. The average rate of readmission per day was 1.1% for days 1–7, 0.8% for days 7–14, 0.5% for days 14–30, and 0.2% for days 30–90. The 30-day readmission rates were 12.6%, 19.7% and 29.2% among hospitalizations resulting in a routine discharge home, a discharge with home health care, and discharge to a skilled nursing facility, respectively.

Table 1.

Comparison of 30-day readmissions, length of stay, hospital mortality, and costs of care between congestive heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, and sepsis from 2009–2011 in California.

| CHF | 2009–2011 AMI |

Sepsis | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| All hospitalizations | 208,794 | 135,980 | 310,565 |

|

| |||

| Index hospitalizations | 193,153 | 105,684 | 240,198 |

|

| |||

| 30 day readmissions | 45,651 | 18,707 | 48,988 |

|

| |||

| 30 day readmission rate | 23.6% | 17.7% | 20.4% |

|

| |||

| Length of stay (Days) | |||

| All hospitalizations* | |||

| Mean (SD) | 4.8 (5.8) | 4.5 (5.9) | 8.7 (11.5) |

|

|

|||

| Median (IQR) | 3 (2–6) | 3 (2–5) | 6 (3–10) |

|

|

|||

| Index hospitalizations† | |||

| Mean (SD) | 4.6 (5.2) | 4.8 (5.4) | 8.5 (10.3) |

|

|

|||

| Median (IQR) | 3 (2–6) | 3 (2–6) | 6 (3–10) |

|

|

|||

| 30 day readmissions‡ | |||

| Mean (SD) | 5.2 (6.1) | 4.4 (6.3) | 10.6 (13.0) |

|

|

|||

| Median (IQR) | 4 (2–6) | 3 (1–5) | 7 (4–13) |

|

| |||

| Hospital Mortality | |||

| All hospitalizations* | 3.1% | 5.6% | 15.9% |

|

|

|||

| Index hospitalizations† | N/A | N/A | N/A |

|

|

|||

| 30 day readmissions‡ | 1.7% | 1.4% | 6.5% |

|

| |||

| Costs per Hospitalization (US $) | |||

| All hospitalizations* | |||

| Mean (SD) | 14,553 (21,693) | 23,683 (26,406) | 26,614 (35,395) |

|

|

|||

| Median (IQR) | 8,870 (5,455–15,655) | 16,550 (9,095–27,734) | 15,462 (8,443–30,180) |

|

|

|||

| Index hospitalizations† | |||

| Mean (SD) | 13,843 (19,356) | 24,492 (24,855) | 24,318 (31,306) |

|

|

|||

| Median (IQR) | 8,738 (5,424–15,202) | 17,810 (10,591–28,706) | 14,829 (8,334–27,741) |

|

|

|||

| 30 day readmissions‡ | |||

| Mean (SD) | 15,081 (23,769) | 22,874 (29,422) | 30,646 (37,932) |

|

|

|||

| Median (IQR) | 8,973 (5,465–15,965) | 14,075 (7,036–26,200) | 18,794 (10,260–35,386) |

All hospitalizations: Hospitalizations after excluding age < 18, missing length of stay and patient identifier variable, admissions to rehabilitation or psychiatric facilities

Index hospitalizations: Hospitalizations after above exclusions that did not result in transfer to another acute care hospital or patient death. All hospitalizations occurring in December of each calendar year were also excluded to allow all index admissions to have a 30 day window for rehospitalization.

30-day readmission: Hospitalizations with at least 1 subsequent hospital stay within 30 days of an index hospitalization.

Abbreviations: CHF, congestive heart failure; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range; US, United States; $, dollars

Figure 1.

Sepsis Readmission Rates for 2009–2011. The all-cause 30-day readmission rates for sepsis were 20.7%, 20.5%, and 20.1% for 2009, 2010, and 2011, respectively. Approximately 7% of patients were readmitted within 7 days after discharge from an index hospitalization for sepsis. Within 90 days of an index hospitalization, over 30% of patients were readmitted. The rate of 7, 14, 30, and 90-day readmissions decreased slightly from 2009 to 2011.

The 30-day readmission rates following hospitalizations for CHF and AMI were 23.6% and 17.7%, respectively (Table 1). Median lengths of stay and in-hospital mortality were greater for sepsis than for CHF and AMI (Table 1). From 2009 through 2011, the total number of 30-day readmissions in California was 48,988 for sepsis, 45,651 for CHF, and 18,707 for AMI. Median cost of hospitalization was $15,462 (IQR $8,443–30,180) for sepsis, $16,550 (IQR $9,095–27,734) for AMI, and $8,870 (IQR $5,455–15,655) for CHF (Table 1). Median cost of a readmission within 30 days was $18,794 (IQR $10,260–35,386) for sepsis, $14,075 (IQR $7,036–26,200) for AMI and $8,973 (IQR $5,465–15,965) for CHF. Estimated annual costs of all 30-day readmissions in California during the study period were $500 million/year for sepsis, $229 million/year for CHF, and $142 million/year for AMI. The trends in 30-day readmission rates, lengths of stay, mortality, and costs by year are shown in the Online Supplement (Supplemental Digital Content Table 5).

Hospital-level Variation in 30-day Readmissions

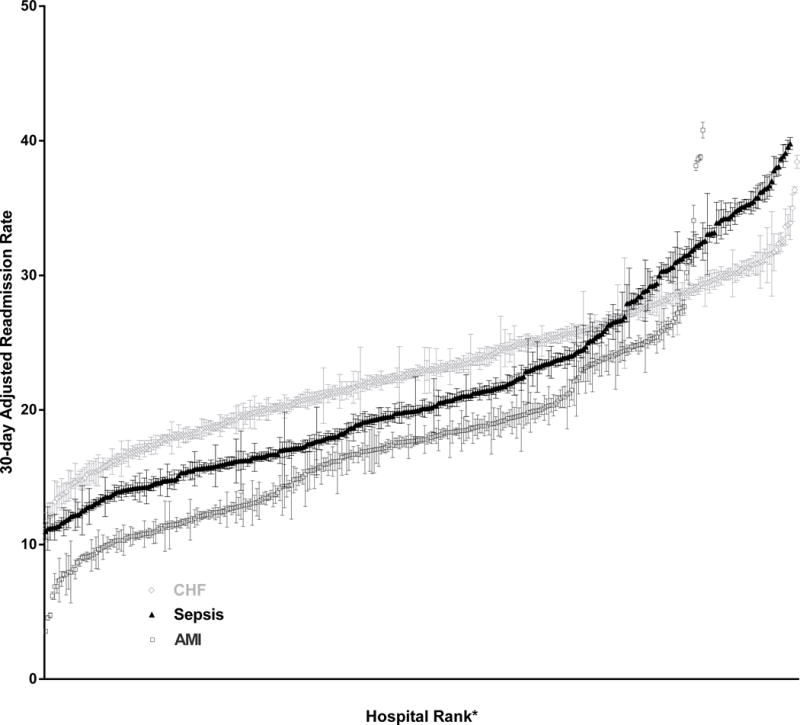

There were 346 California hospitals eligible for the study in the dataset. After excluding hospitals with less than10 annual hospitalizations for each diagnosis, 325 hospitals for sepsis, 328 hospitals for CHF, and 287 hospitals for AMI were included in the variability analysis. The risk and reliability-adjusted readmission rates for sepsis ranged from 11.0% to 39.8% (median 19.9%, IQR 16.1–26.0%) and varied significantly across hospitals (P<0.001). As an example of the magnitude of variation in readmissions across hospitals, the adjusted rates for hospitals 1 SD above versus below the mean were 33.7% (95% CI, 33.0–34.5%) versus 13.0% (95% CI, 12.7–13.3%), respectively. Hospitals in the 90th percentile were 2.5 times more likely to have a 30-day readmission for sepsis than those in the lowest 10th percentile (34.0% versus 13.8%). This variation is shown in the caterpillar plot where each hospital was ranked according to their risk-adjusted rate of 30-day readmissions following hospitalization for sepsis, CHF, and AMI (Figure 2). The overall variation between hospitals for sepsis and CHF were similar (Figure 2). Hospitals had higher variability in 30-day readmission rates for AMI, compared to sepsis and CHF (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Variation of Adjusted 30-Day Readmission Rates in California Hospitals for Sepsis. The risk and reliability adjusted proportion of 30-day readmissions at each hospital ranged from 11.0% to 39.8% (median 19.9%, IQR 16.1–26.0%) for sepsis (black triangle), 11.3% to 38.4% (median 22.9%, IQR 19.2 – 26.6%) for CHF (light gray diamond), and 3.6% to 40.8% (median 17.0%, IQR 12.2–20.0%) for AMI (dark gray square). The 30-day readmission rates were adjusted for age and the number of medical co-morbidities. The error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

*N=287 for AMI, 328 for CHF, and 325 for sepsis

Diagnoses on Readmissions

Septicemia was the most common diagnosis on 30-day readmission following sepsis, and comprised 29.2% of the readmissions (Supplemental Digital Content- Table 3). Pneumonia (4.8%) and respiratory failure (4.1%) were the next most common diagnoses (Supplemental Digital Content- Table 3). The distribution of the most common clinical diagnosis categories for 30-day readmissions following sepsis is summarized in Figure 3. Infections accounted for 59.3% of the primary diagnoses on readmission at 30-days following an index hospitalization (Figure 3). Frequencies of the diagnoses and clinical categories for 7, 14, 30, and 90-day readmissions are shown in the Online Supplement (Supplemental Digital Content Tables 3 and 4).

Figure 3.

Sepsis Readmission Diagnosis Categories. Infections were the most common diagnosis category on 7, 14, 30, and 90-day readmissions and comprised nearly 60% of the cases. Pulmonary diagnoses were the second most common cause, comprising 12–16% of cases. The proportion of readmissions caused by infections remained stable over the first 90 days after the index hospitalization, while pulmonary causes decreased over that time.

Patient and Hospital-level Factors Associated with 30-day Readmission

Among patient-level factors, younger age (OR 1.34, 95% CI 1.29–1.39, between the youngest and oldest age categories), Black (OR 1.29 compared to White, 95% CI 1.24–1.33) and Native-American (OR 2.39 compared to White, 95% CI 1.79–3.19) race, lower income (OR 1.13, 95% CI 1.10–1.16, between the lowest and highest income quartiles), residence in metropolitan areas, and greater burden of medical co-morbidities were associated with higher odds of 30-day readmission following hospitalization for sepsis (Supplemental Digital Content- Table 6). Female gender was associated with lower odds of 30 day readmission (OR 0.87 compared to males, 95% CI 0.86–0.89). Hospital-level characteristics most strongly associated with 30-day readmissions included hospitalizations at an institution delivering healthcare to the highest proportion of minorities (OR 1.28 for quintile of hospitals that had the highest proportion of minorities compared to the lowest quintile, 95% CI 1.23–1.34) and for-profit (OR 1.34, 95% CI 1.31–1.38) or university (OR 1.35, 95% CI 1.26–1.44) hospitals. In contrast, hospitalizations for sepsis in public hospitals were less likely to have 30-day readmissions compared to non-profit hospitals (OR 0.85, 95% CI 0.82–0.89). The c-statistic of the sepsis model was 0.68.

The patient and hospital-level variables that were associated with higher odds of 30-day readmissions were generally similar between sepsis and CHF (Supplemental Digital Content- Table 6). In contrast, there was a stronger association between hospital-level characteristics, including hospital size, teaching status, and proportion of minority patients, and 30-day readmissions for AMI than for sepsis or CHF (Supplemental Digital Content- Table 6).

Sensitivity Analysis

Using the Angus implementation to identify hospitalizations for severe sepsis, the all-cause 30-day readmission rate in 2011 was 23.3% (Supplemental Digital Content-Table 8). The number of sepsis cases in 2011 that were identified by the Angus implementation was greater than by the Martin implementation (236,932 vs. 119,342 cases, respectively). As a result, the annual cost of sepsis readmissions was greater using the Angus implementation compared to the Martin implementation ($1.6 billion versus $612 million, respectively). The patient and hospital-level factors that were associated with 30-day readmissions were similar between the Martin and Angus implementations (Supplemental Digital Content-Table 9).

DISCUSSION

Recent reports from the AHRQ showed that the U.S. healthcare system spends more money on hospitalizations for sepsis than any other cause.[10][30] The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission estimated that 75% of rehospitalizations may be avoidable and contribute to over $10 billion in excess health care costs for Medicare patients alone.[31] In this study, we used a large statewide database to show that about 20% of hospitalizations for sepsis result in readmission within 30-days of hospital discharge. This rate is similar to other high risk medical conditions, such as CHF (23%) and AMI (18%). However, when one accounts for its higher prevalence, the total cost of 30-day readmissions for sepsis was greater than that for CHF and AMI combined; from 2009 to 2011, the annual cost of 30-day readmissions for sepsis in California was approximately $500 million/year, more than twice that for CHF ($229 million/year) and over three times that for AMI ($143 million/year). These findings show that sepsis is a leading contributor to excess healthcare costs due to hospital readmissions.

In addition to the high cost, we observed wide variation in the rates of 30-day readmissions following sepsis between hospitals despite adjusting for case-mix. Hospitals in the 90th percentile were 2.5 times more likely than those at the 10th percentile to have a 30-day readmission after hospitalization of a comparable patient. This range of variability in readmission rates between hospitals for sepsis is similar to that of CHF. These findings suggest that, like CHF, important institutional factors are contributing to differences in readmission rates and imply that examining the differences between high- and low-performing hospitals may inform the development of interventions at the policy and clinical levels to improve the quality of care.

Our study provides some context from which interventions that reduce readmissions for sepsis can be conceptualized. Previous studies showed that interventions that focus on the most prevalent causes of readmissions and target patients at highest risk for readmission are likely to have the greatest efficacy.[1, 32–36] Our analysis shows that when readmissions occur following sepsis, nearly 30% are due to another episode of sepsis and 60% are due to infections. These findings are consistent with a recent study by Ortego, et al. in which 29 out of 63 (46%) patients who survived hospitalization for septic shock were readmitted within 30 days due to an infection-related cause.[12] Nearly 40% of patients who were hospitalized for sepsis in our study were discharged to skilled nursing facilities. Thus, it is likely that any interventions that are hospital-based and do not include collaborative efforts with skilled nursing facilities will have limited efficacy. Notably, patients who were hospitalized with sepsis were also more likely to have co-morbidities, such as dementia and malignancy, in which appropriate interventions may not be improvements in medical management or transitions in care, but instead patient-centered discussions that define the appropriateness of aggressive care, including rehospitalization. The findings from our study suggest that patients and families should be apprised of both the high morbidity in sepsis and the likely range of outcomes among survivors, including the high probability of extended morbidity resulting in rehospitalization and convalescence in skilled nursing facilities. Understanding these potential outcomes will allow patients, families, and healthcare providers to make the most informed choices regarding the care of patients with sepsis.

Our findings are consistent with Prescott et al.’s report of a 30-day readmission rate of 26.5% in a nationally representative sample of 1,083 Medicare patients hospitalized for severe sepsis, Liu et al.’s study that identified a 30-day readmission rate of 17.9% following sepsis among patients enrolled in a large California health maintenance organization, and Ortego et als.’s report of a 30-day readmission rate of 23.4% among survivors of septic shock from a single academic medical center.[9, 10, 12] We extend the findings of these studies by showing that in a large, diverse all-payer population, the impact of sepsis readmissions on the healthcare expenditure far exceeds that of other high risk conditions that are current targets of hospital and policy-level interventions. Many risk factors for readmissions identified in our study, such as minority race/ethnicity and Medicare payment status, were present across all three medical conditions that were examined, and support the existing medical literature on rehospitalizations following AMI, CHF, and CAP.[37–39] The consistency of our findings with these studies supports the validity of our results, and suggests that many risk factors for readmission are not unique to sepsis but instead affect the likelihood of rehospitalization regardless of the underlying diagnosis.

There are some limitations to consider when interpreting the findings of our study. First, we used claims data to identify cases of sepsis, readmission rates, and diagnoses on readmissions. Although there is a lack of literature that examines the accuracy of ICD-9 coding comparing CHF and AMI to sepsis, we used case definitions and clinical classification methods which have been previously validated in order to minimize potential biases associated with the use of administrative data.[7, 17] The Martin implementation was used in our study because it accurately identifies hospitalizations for sepsis with a bias towards underestimating the number of cases.[7] Because we compared the cost of sepsis readmissions relative to CHF and AMI, using a coding scheme that underestimates the number of sepsis hospitalizations was the most conservative approach. The sensitivity analysis using the Angus implementation to identify cases of severe sepsis showed greater than a two-fold increase in the total number and annual cost of sepsis readmissions. These differences highlight the difficulty of accurately estimating the number of sepsis hospitalizations. Such discrepancies may be further complicated by changing coding practices for sepsis and the fact that sepsis remains a challenging diagnosis for clinicians. Despite these limitations, the sensitivity analysis suggests that the impact of sepsis on the overall problem of hospital readmissions may be even greater than presented in our study, further supporting our interpretation of the need to include sepsis among the conditions targeted to improve the readmissions problem. Second, the data were derived from the state of California and may not translate to other healthcare environments. However, the consistency of our results with other studies that have examined healthcare utilization in sepsis using national databases and from hospitals outside of California support the generalizability of our findings.[10, 12, 37–39] Finally, although we identified the most common causes of readmissions following sepsis and some associated risk factors, these associations do not explain the underlying mechanisms through which these rehospitalizations occur. Future studies will need to closely examine the causative events that lead to sepsis readmissions and to differentiate whether they occur as a result of sub-standard care during the index hospitalization or due to patient-related factors that predispose to rehospitalization irrespective of the quality of care. This is an important direction for future studies as certain patient characteristics, such as Black and Native American race and lower income, portend a higher risk of readmissions, suggesting disparities in the quality of care that is being delivered. Understanding the contribution of these factors will also lead to a greater understanding of mutability of sepsis readmissions and the types of interventions that would be most effective.

CONCLUSION

The findings of our study highlight the centrality of sepsis to the problem of hospital readmissions. If future studies and policies that seek to improve the quality and efficiency of healthcare by reducing hospital readmissions are to be effective, they will need to address the problem of readmissions for sepsis, at least on a comparable level to congestive heart failure and acute myocardial infarction.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We affirm that all persons who contributed significantly to the work were listed. Martin F. Shapiro, MD, PhD was supported by NIH/NCATS Grant # UL1TR000124.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Drs. Chang, Tseng, and Shapiro have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Kripalani S, Theobald CN, Anctil B, Vasilevskis EE. Reducing hospital readmission rates: current strategies and future directions. Annual review of medicine. 2014;65:471–485. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-022613-090415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weissman JS, Ayanian JZ, Chasan-Taber S, Sherwood MJ, Roth C, Epstein AM. Hospital readmissions and quality of care. Medical care. 1999;37(5):490–501. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199905000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. The New England journal of medicine. 2009;360(14):1418–1428. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0803563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Lidicker J, Clermont G, Carcillo J, Pinsky MR. Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Critical care medicine. 2001;29(7):1303–1310. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iwashyna TJ, Ely EW, Smith DM, Langa KM. Long-term cognitive impairment and functional disability among survivors of severe sepsis. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 2010;304(16):1787–1794. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lagu T, Rothberg MB, Shieh MS, Pekow PS, Steingrub JS, Lindenauer PK. Hospitalizations, costs, and outcomes of severe sepsis in the United States 2003 to 2007. Critical care medicine. 2012;40(3):754–761. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318232db65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin GS, Mannino DM, Eaton S, Moss M. The epidemiology of sepsis in the United States from 1979 through 2000. The New England journal of medicine. 2003;348(16):1546–1554. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mayr FB, Yende S, Angus DC. Epidemiology of severe sepsis. Virulence. 2014;5(1):4–11. doi: 10.4161/viru.27372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu V, Lei X, Prescott HC, Kipnis P, Iwashyna TJ, Escobar GJ. Hospital readmission and healthcare utilization following sepsis in community settings. Journal of hospital medicine: an official publication of the Society of Hospital Medicine. 2014;9(8):502–507. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prescott HC, Langa KM, Liu V, Escobar GJ, Iwashyna TJ. Increased 1-year healthcare use in survivors of severe sepsis. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2014;190(1):62–69. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201403-0471OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elixhauser A, S C. Readmissions to U.S. Hospitals by Diagnosis. Statistical Brief #153 Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project 2013. 2013 Apr;:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ortego A, Gaieski DF, Fuchs BD, Jones T, Halpern SD, Small DS, Sante SC, Drumheller B, Christie JD, Mikkelsen ME. Hospital-Based Acute Care Use in Survivors of Septic Shock. Critical care medicine. 2014 doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) databases. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, MD: Jun, 2014. http://hcup-us.ahrq.gov/databases.jsp Accessed June 27,2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Cost-to-Charge Ratio Files, July 2014. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, MD: Jun 28, 2014. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/state/costtocharge.jsp. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Talmor D, Greenberg D, Howell MD, Lisbon A, Novack V, Shapiro N. The costs and cost-effectiveness of an integrated sepsis treatment protocol. Critical care medicine. 2008;36(4):1168–1174. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318168f649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development. Hospital Data/Financial. 2012 Jun 28; www.oshpd.ca.gov/HID/Dataflow/HospMain.html.

- 17.Iwashyna TJ, Odden A, Rohde J, Bonham C, Kuhn L, Malani P, Chen L, Flanders S. Identifying Patients With Severe Sepsis Using Administrative Claims: Patient-Level Validation of the Angus Implementation of the International Consensus Conference Definition of Severe Sepsis. Medical care. 2012 doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318268ac86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dharmarajan K, Hsieh AF, Lin Z, Bueno H, Ross JS, Horwitz LI, Barreto-Filho JA, Kim N, Bernheim SM, Suter LG, et al. Diagnoses and timing of 30-day readmissions after hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 2013;309(4):355–363. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.216476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keenan PS, Normand SL, Lin Z, Drye EE, Bhat KR, Ross JS, Schuur JD, Stauffer BD, Bernheim SM, Epstein AJ, et al. An administrative claims measure suitable for profiling hospital performance on the basis of 30-day all-cause readmission rates among patients with heart failure. Circulation Cardiovascular quality and outcomes. 2008;1(1):29–37. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.802686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krumholz HM, Lin Z, Drye EE, Desai MM, Han LF, Rapp MT, Mattera JA, Normand SL. An administrative claims measure suitable for profiling hospital performance based on 30-day all-cause readmission rates among patients with acute myocardial infarction. Circulation Cardiovascular quality and outcomes. 2011;4(2):243–252. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.110.957498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Supplemental Variables for Revisit Analysis, June 2014. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, MD: Jun 28, 2014. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/revisit/revisit.jsp. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lindenauer PK, Lagu T, Shieh M, Pekow PS, Rothberg MB. ASsociation of diagnostic coding with trends in hospitalizations and mortality of patients with pneumonia, 2003–2009. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 2012;307(13):1405–1413. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.HCUP CCS. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, MD: Apr, 2004. www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp. Accessed June 27, 2104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 1992;45(6):613–619. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. Journal of chronic diseases. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.D’Hoore W, Bouckaert A, Tilquin C. Practical considerations on the use of the Charlson comorbidity index with administrative data bases. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 1996;49(12):1429–1433. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(96)00271-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morris CN. Parametric Empirical Bayes Inference: Theory and Applications. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1983;78(381):47–55. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Normand S-LT, Glickman ME, Gatsonis CA. Statistical Methods for Profiling Providers of Medical Care: Issues and Applications. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1997;92(439):803–814. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seymour CW, Iwashyna TJ, Ehlenbach WJ, Wunsch H, Cooke CR. Hospital-level variation in the use of intensive care. Health services research. 2012;47(5):2060–2080. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01402.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Torio CM, Andrews RM. National inpatient hospital costs: the most expensive conditions by payer. 2011 HCUP Statistical Brief #160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.MedPac. Report to the Congress: reforming the delivery system. Washington, DC: Medicare Payment Advisory Committee; 2007. Payment Policy for Inpatient Readmissions. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Evans RL, Hendricks RD. Evaluating hospital discharge planning: a randomized clinical trial. Medical care. 1993;31(4):358–370. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199304000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hansen LO, Young RS, Hinami K, Leung A, Williams MV. Interventions to Reduce 30-Day Rehospitalization: A Systematic Review. Annals of internal medicine. 2011;155(8):520–528. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jack BW, Chetty VK, Anthony D, Greenwald JL, Sanchez GM, Johnson AE, Forsythe SR, O’Donnell JK, Paasche-Orlow MK, Manasseh C, et al. A reengineered hospital discharge program to decrease rehospitalization: a randomized trial. Annals of internal medicine. 2009;150(3):178–187. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-3-200902030-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koehler BE, Richter KM, Youngblood L, Cohen BA, Prengler ID, Cheng D, Masica AL. Reduction of 30-day postdischarge hospital readmission or emergency department (ED) visit rates in high-risk elderly medical patients through delivery of a targeted care bundle. Journal of hospital medicine: an official publication of the Society of Hospital Medicine. 2009;4(4):211–218. doi: 10.1002/jhm.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Naylor M, Brooten D, Jones R, Lavizzo-Mourey R, Mezey M, Pauly M. Comprehensive discharge planning for the hospitalized elderly. A randomized clinical trial. Annals of internal medicine. 1994;120(12):999–1006. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-120-12-199406150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Joynt KE, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Thirty-day readmission rates for Medicare beneficiaries by race and site of care. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 2011;305(7):675–681. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Philbin EF, Dec GW, Jenkins PL, DiSalvo TG. Socioeconomic status as an independent risk factor for hospital readmission for heart failure. The American journal of cardiology. 2001;87(12):1367–1371. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)01554-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Philbin EF, DiSalvo TG. Prediction of hospital readmission for heart failure: development of a simple risk score based on administrative data. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1999;33(6):1560–1566. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00059-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.