Abstract

Background:

Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) is a common complication after general anesthesia, and the prevalence ranges between 25% and 30%. The aim of this study was to determine the preventive effects of dry cupping on PONV by stimulating point P6 in the wrist.

Methods:

This was a randomized controlled trial conducted at the Imam Reza Hospital in Kermanshah, Iran. The final study sample included 206 patients (107 experimental and 99 controls). Inclusion criteria included the following: female sex; age>18 years; ASA Class I-II; type of surgery: laparoscopic cholecystectomy; type of anesthesia: general anesthesia. Exclusion criteria included: change in the type of surgery, that is, from laparoscopic cholecystectomy to laparotomy, and ASA-classification III or more. Interventions are as follows: pre surgery, before the induction of anesthesia, the experimental group received dry cupping on point P6 of the dominant hand's wrist with activation of intermittent negative pressure. The sham group received cupping without activation of negative pressure at the same point. Main outcome was that the visual analogue scale was used to measure the severity of PONV.

Results:

The experimental group who received dry cupping had significantly lower levels of PONV severity after surgery (P < 0.001) than the control group. The differences in measure were maintained after controlling for age and ASA in regression models (P < 0.01).

Conclusion:

Traditional dry cupping delivered in an operation room setting prevented PONV in laparoscopic cholecystectomy patients.

Keywords: cupping, laparoscopic cholecystectomy, PONV

Terms used in this study are based on the following definitions

Nausea refers to the unpleasant feeling of throwing up without retching or evacuation of the stomach's contents.

Vomiting refers to pushing out the stomach's contents through the mouth or nose.

Retching (dry heaving) is the reverse movement (peristalsis) of the stomach and esophagus without vomiting.

Early PON and POV refer to nausea and vomiting up to 2 hours post post-operation.

Delayed PON and POV refer to nausea and vomiting.

Rescue therapy (liberation therapy) refers to the use of at least one dose of ondansetron 2 mg within 24 hours after surgery.[1]

Cupping (Suction position): stimulation of a point on skin to create suction and desired effect.[2]

1. Introduction

Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) is one of the most common complications of general anesthesia.[3] About 30% of surgical cases report unpleasant experiences after general anesthesia.[4] PONV is one of the most common concerns reported by patients’ preoperation visits, even more so than pain,[5] as well as a cause of patient dissatisfaction post-operation.[6] Moreover, PONV is associated with other serious complications, such as aspiration, wound dehiscence, pneumothorax, subcutaneous emphysema, and even esophageal rupture.[7,8] Therefore, anesthesiologists and surgeons consider the control of PONV an important treatment priority.

There are a number of drugs to reduce the risk of PONV; however, in addition to their costs, their adverse effects limit their usage in routine clinical practice.[9–11] For example, Droperidol is black-boxed because it is a risk factor for cardiac arrhythmias.[12] As a result, there is great need for nonpharmacologic techniques (NPTs) and complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) to treat PONV.

Acupuncture stimulation of the point P6 (acupuncture points) has been shown to significantly control nausea and vomiting in a World Health Organization (WHO) study.[13] Moreover, stimulated P6 also has analgesic effects.[14] The location of point P6 point is between the flexor carpi radialis and the palmaris longus muscle tendons, about 2 inches proximal to the distal crease of the wrist (Fig. 1).[15] Stimulation of this point has been tested in several ways, including in acupuncture, acupressure, electrical stimulation, acoustic stimulation, and so on.[15]

Figure 1.

P6 anatomical areas of dry-cupping for postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV).

Cupping therapy is a 2000-year-old form of CAM, and depending on its application is classified as dry or wet cupping.[16] Wet cupping involves bloodletting, that is, the evacuation of morbid humor from affected areas.[16] Dry cupping involves diverting morbid matters from one site to another by applying quick, vigorous, rhythmical strokes on intact skin (without bloodletting). Therefore, dry cupping is considered to be a noninvasive and inexpensive technique.[17] More specifically, in this technique, the underlying tissues are pulled into the suctioning cupping glass by heat production to increase the local blood and lymphatic circulation.[18] Although this technique has been used in the treatment of numerous conditions including excessive menstrual bleeding, edema, scrotal hernia, sciatica, hydrocele, postpartum perineal pain, chronic neck pain, and low back pain,[19–24] we are not aware of any previous studies testing the effectiveness of dry cupping in the treatment of PONV.

Considering the fewer side effects of this therapy compared to other medicinal therapies and the lack of available clinical trials on dry cupping and PONV,[24] the present study we aimed to test the preventive effects of dry cupping through stimulation of the P6 on postoperative nausea (PON) and postoperative vomiting (POV), as well as reducing the number of cases requiring rescue therapy (that is, need to treat [NNT]). This is the first time dry cupping therapy has been employed in treatment of PONV.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design, participants, sample size

This study was a single-center observer-blind randomized clinical trial that was carried out between January and December 2014 at Imam Reza hospital, a university hospital affiliated with Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences in Iran. The inclusion criteria were selected based on previous studies using the Apfel scale and included the following: female sex; age >18 years; ASA Class I-II; scheduled surgery (laparoscopic cholecystectomy); and type of anesthesia (general anesthesia).[7,25,26] Exclusion criteria include: change in the type of surgery, that is, from laparoscopic cholecystectomy to laparotomy, and ASA-classification III or more.

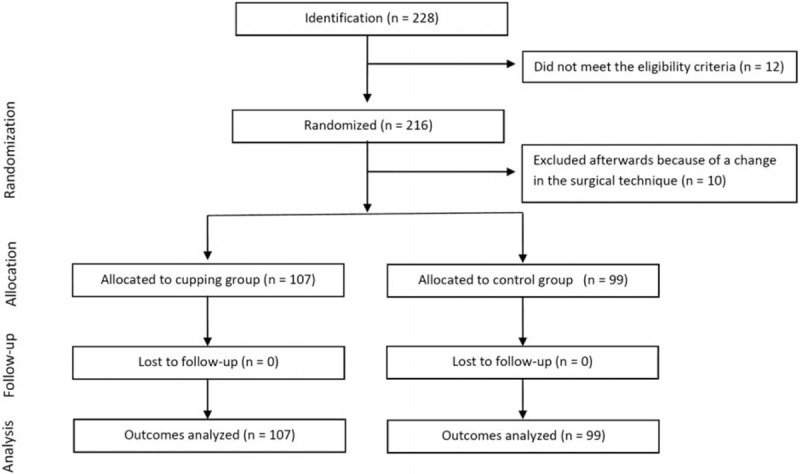

A general practitioner who was part of the study group screened 228 patients. Twelve patients were excluded because of having an ASA III or more. This resulted in 216 consenting patients, 10 of whom were excluded because of a change in their surgical procedures, which resulted in a final sample size of 206 patients (CONSORT Flow Diagram, Fig. 2). Subsequently, the study therapist (a physician with several years of experience in cupping) obtained the randomization allocation by the research coordinator who used a computer program to generate the random allocation sequence and had no contact with study patients. Only the therapist knew the randomization result. The patients and the observer of the endpoints were not informed about the allocation. Using a sham technique ensured blinding of the patients before receiving general anesthesia.

Figure 2.

Patients progress thoughts the trial: CONSORT flowchart.

According to the findings of an earlier observer-blind, randomized controlled PONV trial[27] (P1 = 0.63, P2 = 0.33) and a power of 95%, a minimum sample size for each group was 53 and a total of 106 cases and control. We increased the sample size to 206 to increase the quality of the study and to control for the effect of confounding variables such as anxiety.

Ten minutes before the induction of anesthesia, all patients received midazolam 1 mg/iv/stat as premedication. This was followed by an infusion of 100 mL of Ringer lactate over 10 minutes, after which the induction of anesthesia started by sodium thiopental (5 mg/kg), sufentanil (0.2 μg/kg), and atracurium (0.5 mg/kg). The maintenance continued with isoflurane (end-tidal between 0.8 and 1.6) and oxygen (7 L/min without N2O). During the operation, patients were observed carefully while receiving crystalloids (Ringer lactate). Ten minutes before the end of surgery, all patients received morphine (0.05 mg/kg) or meperidine (0.5 mg/kg). After the surgery, 10 minutes before leaving the post-anesthesia care unit (PACU), analgesic therapy (morphine 0.05 mg/kg) was repeated for all patients. Rescue therapy with ondansetron 2 mg was used for all patients with moderate or severe nausea episodes or if patients requested to have treatment for nausea or vomiting.[27]

In both groups, after injection of premedication (midazolam 1 mg, 10 minutes before induction), a 30- to 40-cc cup, fitting the patient's wrist, was placed on the dominant hand P6 point. In the experimental group, after the induction of anesthesia, negative pressure (60–100 mmHg) was induced. In the sham group, the cup was remained inactive without negative pressure. The visual analogue scale (VAS) was used to evaluate PONV in patients at 2, 6, and 24 hours after surgery. Anxiety levels before receiving premedication (before injection of midazolam), as well as 2, 6, and 24 hours after surgery were assessed by VAS and both groups were matched for anxiety.

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the local ethics committee of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences in Imam Reza hospital and is listed in the Iranian registry of clinical trials (IRCT2011020131ON6).

All data are presented as mean and standard deviation (SD) unless otherwise indicated. Parametric variables (anxiety, nausea, vomiting, retching, recuse therapy, analgesic satisfaction) were compared using an unpaired Student t test. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test (history of motion sickness, migraine headache, or PONV). P values for the risk of PONV or the need of rescue therapy were set at >0.05. The overall, PONV was defined as at least 1 episode of nausea, retching, or vomiting during the observation time of 24 hour. Rescue therapy was defined as at least 1 dosage of tropisetron during the observation time of 24 hour. Adjusted logistic regression analysis was performed in a stepwise backward fashion with the indicated variables as covariates. Differences were regarded statistically significant with an alpha error of >0.05. All statistical analyses were 2-sided and were performed using SPSS, version 21.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

3. Results

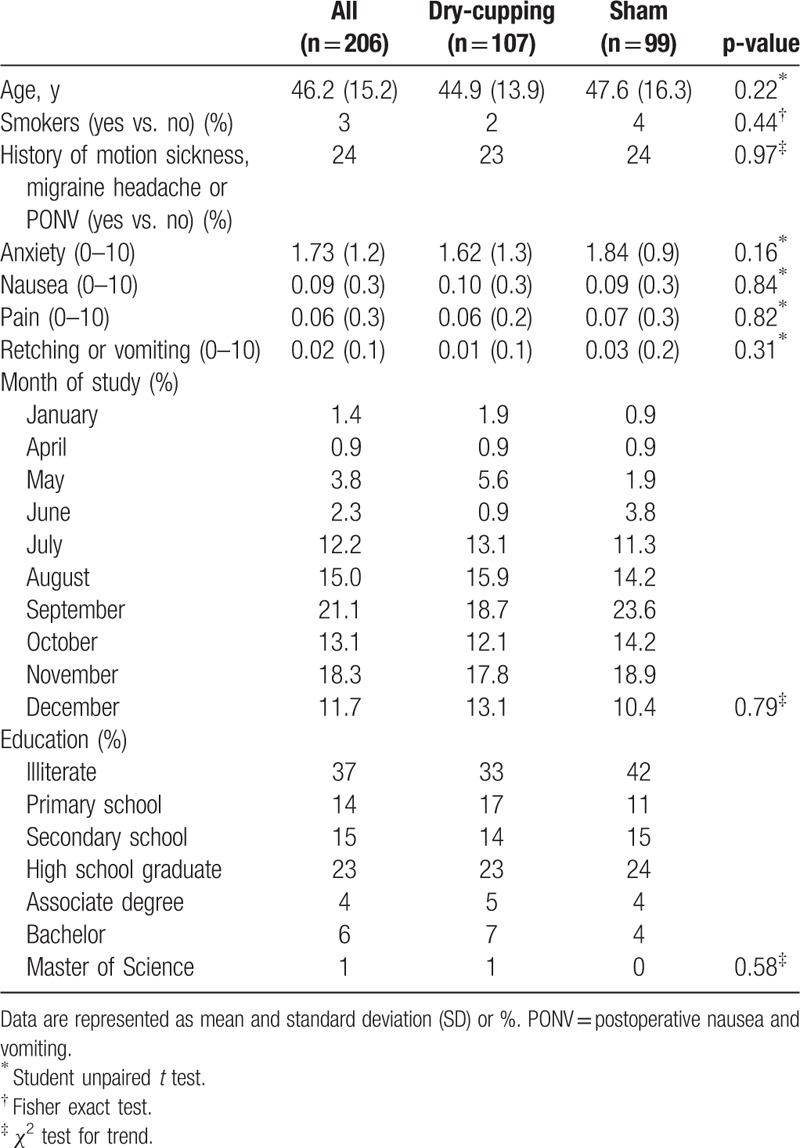

The average age of patients in the intervention group was 44.9 ± 13.9 years and in the control group was 47.9 ± 16.3 years, and the difference between the 2 groups was not statistically significant (P > 0.05). As indicated in Table 1, the 2 groups were similar with respect to smoking status, history of motion sickness, migraine headache, anxiety, nauseas, pain, retching or vomiting, and education (P > 0.05).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics at baseline by allocation groups.

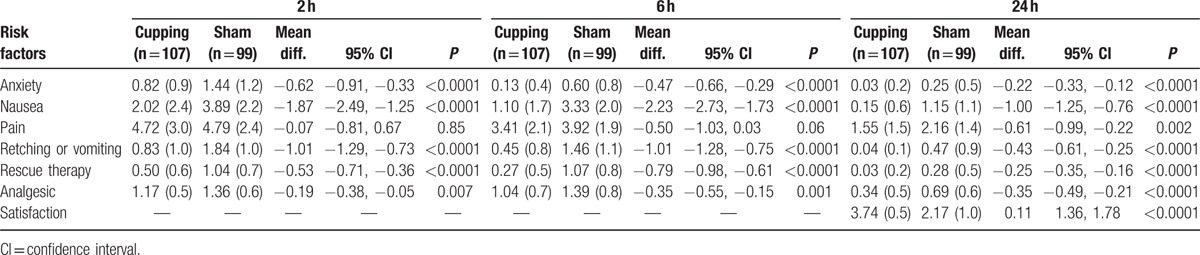

According to the Table 2, dry cupping had significant effect on PONV in the intervention group compared to the control group (sham group). More specifically, the means for nausea in the 2 hours (2.02 vs. 3.89), 6 hours (1.10 vs. 3.33), and 24 hours (0.15 vs. 1.15) were significantly reduced in the intervention group versus the control group (P < 0.001), and the most reducing effect was evident in the 6 hours post-surgery. The means for vomiting also reduced significantly in the experimental group compared to the control group in 2 hours (0.83 vs. 1.84), 6 hours (0.45 vs. 1.46), and 24 hours (0.04 vs. 0.47) (P < 0.001), and the most reduction occurred in the 2 hours post-surgery. Furthermore, the means for rescue therapy at the 2 hours (0.50 vs. 1.04), 6 hours (0.27 vs. 1.07), and 24 hours (0.03 vs. 0.28) reduced in the intervention group compared to the control group (P < 0.001), and the most reduction occurred in the 6 hours post-surgery.

Table 2.

Means (standard deviations), mean difference, 95% CI, and P value for intervention and control groups and comparing both groups (2-tailed tests).

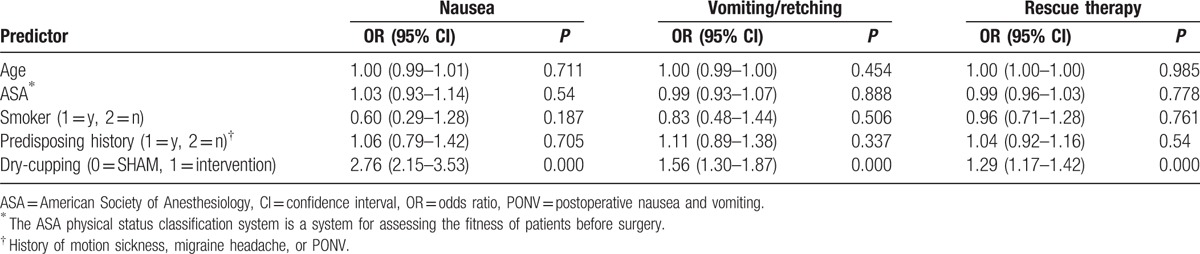

Table 3 illustrates the predictive role of known risk factors on nausea, vomiting, and rescue therapy, as well as the overall predictive role of intervention on these factors. Of the variables in the model, being in the intervention group significantly reduced the likelihood of nausea (odds ratio [OR]: 2.76, confidence interval [CI]: 2.15–3.53), vomiting (OR: 1.56, CI: 1.30–1.87), and need for rescue therapy (OR: 1.29, CI: 1.17–1.42), compared to the control group, controlling for other variables in the model.

Table 3.

Adjusted logistic regression analysis for known risk factors and dry-cupping on the development of PONV and the requirement of rescue therapy.

4. Discussion

Nausea and vomiting are the costly “little big problem” postoperative side effect that compromises patient treatment outcome.[28,29] Nonpharmacological CAM techniques have traditionally helped to relieve nausea and vomiting by stimulating pericardium 6 (P6 nei-guan), located a 3-finger span below the wrist on the inner forearm between the 2 tendons.[24,26,28]

In the present study, the stimulation of P6 by dry cupping had a meaningful effect in reducing nausea, vomiting, and the need for rescue therapy 2 hours, 6 hours, and 24 hours after surgery in the intervention group compared to the control group. The most meaningful effect of dry cupping on nausea was observed in the 6 hours, for vomiting in the first 2 hours, and for need for rescue therapy in 6 hours, post-surgery. When we controlled for PONV known risk factors,[29] patients who received dry cupping were nearly 3 times less likely to report nausea, over one and a half times less likely to report vomiting or retching, and 1.3 times less likely to need rescue therapy, post-surgery.

As one of the modalities of acupuncture, cupping is valued for its potential to strengthen body resistance, to eject pathogenic factors, and to promote blood circulation. These restore the balance between Yin (negative/passive/dark/water) and Yang (positive/active/bright/fire) and promote the flow of “Qi,” which signifies power and movement similar to energy.[16,30]

Several suggestions have been made regarding the possible mode of action in dry cupping. These include adjustment in skin blood flow,[31] influencing biomechanical properties of tissues under treatment,[32] increasing anaerobic metabolism in subcutaneous tissue,[33] modulation of cellular part of the immune system,[34] and generally improving microcirculation. This prompts capillary endothelial cell repair, accelerating granulation and angiogenesis in regional tissues.[18]

This is the first study testing the effectiveness of dry cupping in reducing PONV. The technique used in dry cupping is similar to acupuncture. We therefore use the acupuncture literature to inform us of possible underlying mechanisms of P6 point stimulation in controlling nausea and vomiting.[27,28] It has been suggested that acupuncture may result in low-frequency electrical stimulation of the skin. This causes nerve activity for A-β and A-δ fibers, which may have an effect in nerve transmission in the dorsal horn and upper neurons. Clement-Jones, McLoughlin et al (1980) also reported that the internal opioid system may be involved in the release of enkephalin, endorphins, beta-endorphin, and dynorphin.[35,36] It is also possible that the effect of P6 point stimulation is because of the inhibition of gastric acid secretion and improvement in stomach motion.[15,36]

Confirmatory benefits of sensory effect of stimulation on the wrist in reducing nausea and vomiting compared to placebo device have been reported in pregnant women,[37] in outpatients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy procedures,[38] and in children undergoing anesthesia and surgery.[39,40] In Zarate's study, 221 patients were randomized into: active involvement in the P6; sham group; and placebo. The authors reported that intervention significantly decreased (P < 0.05) the incidence of moderate to severe nausea up to 9 hours after surgery compared to the sham and the placebo groups. No difference was detected in the incidence of vomiting and the need for treatment (escape medication). In the study of 120 children undergoing tonsillectomy, the authors found that electrical P6 acupuncture, although patients were anesthetized, significantly reduced the incidence of PONV in the intervention group compared to the sham puncture and the control group (63% vs. 88% vs. 93%; P < 0.001).[40] Further studies are needed to delineate the underlying palliative mechanism of dry cupping on PONV.

Overall, our findings support previous acupuncture and acupressure findings in that pressure at the P6 point by dry cupping may have a specific therapeutic effect in preventing the incidence of PONV in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy surgery. It is also noteworthy that none of the patients in our study reported unusual side effects. In a systematic review of cupping therapy for acute and chronic pain management Cao et al reported that of 10 randomized clinical trials reported severe adverse effect related to cupping. However, 6 trails reported mild to moderate hematoma, pain, soreness or tingling at the treated site, which are considered common side effects.[24]

4.1. Limitations and future research

Our study had several limitations. First, it is a single-center study. A multicenter study is essential in supporting generalizability of findings. Second, because we included only females in the study, our findings suffer from converge bias in that they are limited to female population. Future studies are needed to replicate our study with males, and different populations such as patients with different body mass indices and those who were administered different anesthetic agents or underwent different anesthesia procedures. Gastric tube decompression, for example, has no apparent effect on PONV, but the use of nasogastric tubes is associated with higher incidence of nausea.[41]

The third limitation involves our lack of control over response bias; high response expectancies may compromise the internal validity of the study.[42,43] As part of the Prophetic Medicine, cupping is worshiped by many.[44] It is suggested that this may involuntarily mediate a participant's response to treatment prerandomization as in obtaining informed consent. Current scientific evidence is mixed in supporting this assertion, because of the lack of standardized measures to assess response expectancies.[42] However, the importance of assessing and comparing groups in terms of their expectancies appears significant.

Expectations of benefit may interfere with trial validity in studies involving sham medical devices by making it difficult to detect between-group differences.[45] This further limits the validity of our findings in that we did not investigate, determine, and measure sham credibility, and relied on its applicability based on previous studies. To overcome these biases, studies with larger samples are needed. These allow for stratified randomization by strength of response expectancy across both control and sham group.[42]

In addition to response expectancies, post-surgery women with real cupping may notice distinctly colored skin over the P6 region because of the negative pressure created during the process. This, of course, would not occur in the control group. Although our patients were blinded to their group assignment, this discoloration effect could introduce additional response bias. Lastly, our study was not designed to establish whether dry cupping was noninferior to acupunctures. Doing so would require studies with larger sample size.

5. Conclusion

Our findings are promising in that they suggest dry cupping treatments at the acupressure P6 can prevent the incidence of nausea, vomiting, and need for rescue therapy after laparoscopic cholecystectomy surgery. Additional clinical studies of dry cupping are needed to investigate its effect in preventing and treating PONV in men, and children undergoing similar surgery. Also, considering that dry cupping is a noninvasive procedure with fewer side effects compared to other medicinal therapy, its prophylactic antiemetic therapy should be investigated for different patients, other types of surgeries and different anesthetic agent or anesthesia procedures. More randomized, controlled multicenter studies are needed. They may provide firm evidence of the effectiveness of dry cupping, and demonstrate its underlying analgesic mechanism in preventing PONV.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences for supporting this project.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ASA class = American Society of Anesthesiology patient classification status, ASA I = Normal healthy patient, ASA II = patient with mild systemic disease; no functional limitation, ASA III = patient with severe systemic disease; definite functional impairment, CAM = complementary and alternative medicine, CI = confidence interval, CONSORT = Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials, NNT = the number need to treat (NNT), NPT = nonpharmacologic techniques, OR = odds ratio, PACU = post-anesthesia care unit, PONV = post-operative nausea and vomiting, SD = standard deviation, VAS = visual analogue scale, WHO = World Health Organization.

This study was registered in the World Health Organization, International Clinical Trials Registry Platform with registration number = IRCT201102011310N6.

This article is the result of an anesthesiology residency project # 89172.

This work was performed in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Specialty of Anesthesiology (MD), of Mohammad Kameli, in faculty of Medicine, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah Iran.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Apfel CC, Roewer N, Korttila K. How to study postoperative nausea and vomiting. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2002; 46:921–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Apfel CC, Kranke P, Eberhart LH, et al. Comparison of predictive models for postoperative nausea and vomiting. Br J Anaesth 2002; 88:234–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antor MA, Uribe AA, Erminy-Falcon N, et al. The effect of transdermal scopolamine for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Front Pharmacol 2014; 5:55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith HS, Smith EJ, Smith BR. Postoperative nausea and vomiting. Ann Palliat Med 2012; 1:94–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Youssef N, Orlov D, Alie T, et al. What epidural opioid results in the best analgesia outcomes and fewest side effects after surgery?: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Anesth Analg 2014; 119:965–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lahsaei SM, Amini A, Tabatabei SM, et al. A comparison between cetirizine and ondansetron in preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting in adults. J Res Med Sci 2012; 17:760–763. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Apfel CC, Laara E, Koivuranta M, et al. A simplified risk score for predicting postoperative nausea and vomiting: conclusions from cross-validations between two centers. Anesthesiology 1999; 91:693–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller RD. Anesthesia. 7th ed.Philadelphia: Churehil livingstone; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kooij FO, Klok T, Hollmann MW, et al. Decision support increases guideline adherence for prescribing postoperative nausea and vomiting prophylaxis. Anesth Analg 2008; 106:893–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kovac AL. Update on the management of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Drugs 2013; 73:1525–1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Apfel CC, Kinjo S. Acustimulation of P6: an antiemetic alternative with no risk of drug-induced side-effects. Br J Anaesth 2009; 102:585–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scuderi PE. Droperidol: many questions, few answers. Anesthesiology 2003; 98:289–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization. Acupuncture: Review and Analysis of Reports on Controlled Clinical Trials. Geneva: WHO; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gan TJ, Jiao KR, Zenn M, et al. A Randomized controlled comparison of electro-acupoint stimulation or ondansetron versus placebo for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg 2004; 99:1070–1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rowbotham DJ. Recent advances in the non-pharmacological management of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Br J Anaesth 2005; 95:77–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mehta P, Dhapte V. Cupping therapy: a prudent remedy for a plethora of medical ailments. J Tradit Complement Med 2015; 5:127–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rozenfeld E, Kalichman L. New is the well-forgotten old: the use of dry cupping in musculoskeletal medicine. Journal of bodywork and movement therapies 2016; 20:173–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cui S, Cui J. Progress of researches on the mechanism of cupping therapy. Zhen Ci Yan Jiu 2012; 37:506–510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akbarzade M, Ghaemmaghami M, Yazdanpanahi Z, et al. Comparison of the effect of dry cupping therapy and acupressure at BL23 point on intensity of postpartum perineal pain based on the short form of mcgill pain questionnaire. J Reprod Infertil 2016; 17:39–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Akbarzadeh M, Ghaemmaghami M, Yazdanpanahi Z, et al. The effect dry cupping therapy at acupoint BL23 on the intensity of postpartum low back pain in primiparous women based on two types of questionnaires, 2012; a randomized clinical trial. Int J Community Based Nurs Midwifery 2014; 2:112–120. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim JI, Lee MS, Lee DH, et al. Cupping for treating pain: a systematic review. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2011; 2011:467014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Farhadi K, Schwebel D, Saeb M, et al. The effectiveness of wet-cupping for nonspecific low back pain in Iran: a randomized controlled trial. Complement Ther Med 2009; 17:9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cramer H, Lauche R, Hohmann C, et al. Randomized controlled trial of pulsating cupping (pneumatic pulsation therapy) for chronic neck pain. Forsch Komplementmed 2011; 18:327–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cao H, Li X, Yan X, et al. Cupping therapy for acute and chronic pain management: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medical Sciences 2014; 1:49–61. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weilbach C, Rahe-meyer N, Raymondos K, et al. Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV): usefulness of the Apfel-score for identification of high risk patients for PONV. Acta Anaesthesiol Belg 2006; 57:361–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harmon D, Gardiner J, Harrison R, et al. Acupressure and the prevention of nausea and vomiting after laparoscopy. Br J Anaesth 1999; 82:387–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frey UH, Scharmann P, Lohlein C, et al. P6 acustimulation effectively decreases postoperative nausea and vomiting in high-risk patients. Br J Anaesth 2009; 102:620–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee A, Fan LTY. Stimulation of the wrist acupuncture point P6 for preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009. CD003281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koivuranta M, Laara E. A survey of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anaesthesia 1998; 53:413–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin Y-C. Perioperative usage of acupuncture. Pediatr Anesth 2006; 16:231–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu W, Piao S-a, Meng X-w, et al. Effects of cupping on blood flow under skin of back in healthy human. World Journal of Acupuncture - Moxibustion 2013; 23:50–52. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen B, Li M-Y, Liu P-D, et al. Alternative medicine: an update on cupping therapy. QJM 2015; 108:523–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Emerich M, Braeunig M, Clement HW, et al. Mode of action of cupping--local metabolism and pain thresholds in neck pain patients and healthy subjects. Complement Ther Med 2014; 22:148–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Samadi M, Kave M, Mirghanizadeh S. Study of cupping and its role on the immune system. J Relig Health 2013. 1.23334953 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clement-Jones V, McLoughlin L, Tomlin S, et al. Increased beta-endorphin but not met-enkephalin levels in human cerebrospinal fluid after acupuncture for recurrent pain. Lancet 1980; 2:946–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin X, Liang J, Ren J, et al. Electrical stimulation of acupuncture points enhances gastric myoelectrical activity in humans. Am J Gastroenterol 1997; 92:1527–1530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Evans AT, Samuels SN, Marshall C, et al. Suppression of pregnancy-induced nausea and vomiting with sensory afferent stimulation. J Reprod Med 1993; 38:603–606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zarate E, Mingus M, White PF, et al. The use of transcutaneous acupoint electrical stimulation for preventing nausea and vomiting after laparoscopic surgery. Anesth Analg 2001; 92:629–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang SM, Kain ZN. P6 acupoint injections are as effective as droperidol in controlling early postoperative nausea and vomiting in children. Anesthesiology 2002; 97:359–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rusy LM, Hoffman GM, Weisman SJ. Electroacupuncture prophylaxis of postoperative nausea and vomiting following pediatric tonsillectomy with or without adenoidectomy. Anesthesiology 2002; 96:300–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kerger K-H, Mascha E, Steinbrecher B, et al. Routine use of nasogastric tubes does not reduce postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg 2009; 109:768–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Prady SL, Burch J, Vanderbloemen L, et al. Measuring expectations of benefit from treatment in acupuncture trials: a systematic review. Complement Ther Med 2015; 23:185–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haller H, Ostermann T, Lauche R, et al. Credibility of a comparative sham control intervention for Craniosacral Therapy in patients with chronic neck pain. Complement Ther Med 2014; 22:1053–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baghdadi H, Abdel-Aziz N, Ahmed NS, et al. Ameliorating role exerted by Al-Hijamah in autoimmune diseases: effect on serum autoantibodies and inflammatory mediators. Int J Health Sci 2015; 9:207–232. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kaptchuk TJ, Goldman P, Stone DA, et al. Do medical devices have enhanced placebo effects? J Clin Epidemiol 2000; 53:786–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]