Abstract

Aim:

To provide an overview of the medical literature on cutaneous fistulization in patients with hydatid disease (HD).

Methods:

According to PRISMA guidelines a literature search was made in PubMed, Medline, Google Scholar, and Google databases were searched using keywords to identify articles related to cutaneous fistulization of the HD. Keywords used were hydatid disease, hydatid cyst, cutaneous fistulization, cysto-cutaneous fistulization, external rupture, and external fistulization. The literature search included case reports, review articles, original articles, and meeting presentations published until July 2016 without restrictions on language, journal, or country. Articles and abstracts containing adequate information, such as age, sex, cyst size, cyst location, clinical presentation, fistula opening location, and management, were included in the study, whereas articles with insufficient clinical and demographic data were excluded. We also present a new case of cysto-cutaneous fistulization of a liver hydatid cyst.

Results:

The literature review included 38 articles (32 full text, 2 abstracts, and 4 unavailable) on cutaneous fistulization in patients with HD. Among the 38 articles included in the study, 22 were written in English, 13 in French, 1 in German, 1 in Italian, and 1 in Spanish. Forty patients (21 males and 19 females; mean age ± standard deviation, 54.0 ± 21.5 years; range, 7–93 years) were involved in the study. Twenty-four patients had cysto-cutaneous fistulization (Echinococcus granulosus); 10 had cutaneous fistulization (E multilocularis), 3 had cysto-cutaneo-bronchio-biliary fistulization, 2 had cysto-cutaneo-bronchial fistulization; and 1 had cutaneo-bronchial fistulization (E multilocularis). Twenty-nine patients were diagnosed with E granulosis and 11 had E multilocularis detected by clinical, radiological, and/or histopathological examinations.

Conclusion:

Cutaneous fistulization is a rare complication of HD. Complicated HD should be considered in the differential diagnosis of cases presenting with cutaneous fistulization, particularly in regions where HD is endemic.

Keywords: alveolar echinococcosis, complications, cystic echinococcosis, cysto-cutaneous fistulization, hydatid disease

1. Introduction

Hydatid disease (HD) is a zoonotic disease caused by Echinococcus sp. parasites (Family Taeniidae; Class Cestoda). Although 4 different Echinococcus sp. cause HD in humans, the most common are E granulosus (causing cystic echinococcosis) and E multilocularis (causing alveolar echinococcosis).[1–6] Cystic echinococcosis, also known as a hydatid cyst (HC), is responsible for 95% of all echinococcal diseases in humans. HCs can be located in almost every organ or tissue of the body, although the liver and lungs are the most commonly involved organs. Nevertheless, the majority of patients are asymptomatic and are incidentally diagnosed by radiology performed for other reasons. Complications, such as rupture, infection, anaphylaxis, and compression of adjacent organs, may cause various clinical symptoms.[2] Among the most severe complications, rupture (perforation or fistulization) is the most important. Liver HCs can rupture into the bile duct, the gastrointestinal tract, bronchi, peritoneal cavity, or pleural cavity. The progression of liver HCs into subcutaneous tissue and fistulization in the skin is a rare complication.[6–12] To date, few case reports on this complication have been published. In this article, we present a case of liver HC that spontaneously fistulized into an incision on the anterior abdominal wall. We also review the relevant literature.

2. Materials and methods

According to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines,[13] a literature search was made in PubMed, Medline, Google Scholar, and Google databases using the keywords hydatid disease, hydatid cyst, cutaneous fistulization, cutaneous involvement, cysto-cutaneous fistulization, external rupture, and external fistulization alone or in different combinations (Flow Diagram). The language, journal, and country were not limited for this literature review. All case reports, letters to the editor, review articles, original articles, and other documents were reviewed. Reference lists of the reviewed papers were also reviewed to include citations that met the inclusion criteria. Articles without an accessible full text version, an abstract providing sufficient information, or sufficient data to compare with other studies were excluded. The following information was collected: publication year, country, publication language, paper type (full text, abstract, or unavailable), age and sex of patients, clinical presentation, Echinococcus sp. (E granulosus or E alveolaris), location of the fistula opening, cyst location, maximum size of cyst/lesion (mm), previous surgery, radiologic tools (ultrasonography [US], computed tomography [CT], magnetic resonance imaging [MRI], and fistulography), neoadjuvant antiparasitic chemotherapy, surgical management, postoperative antiparasitic chemotherapy, recurrence, and follow-up (months). The patient's age was given as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and range. The secondary aim of this study was to document the clinical story and management algorithm for a 56-year-old male patient who was admitted to our clinic with cysto-cutaneous fistulization caused by complicated liver HC. Local ethics committee approval was not needed because this was a retrospective literature review.

3. Results

3.1. Literature review

The literature search retrieved 38 articles involving 40 patients with cutaneous fistulization/HD involvement.[1–12,14–39] Of these, 6 articles were from India, 5 from France, 5 from Tunisia, 4 from Turkey, 4 from Morocco, 3 from Spain, 2 from Germany, 2 from Italy, and 1 each from Japan, Austria, Bulgaria, Greece, Lithuania, Romania, and Switzerland. Twenty-two articles were written in English, 13 in French, 1 in German, 1 in Italian, and 1 in Spanish. Full text was obtained for 32 of the 38 articles, whereas abstracts were available for 2 articles, and no text of any kind was available for 4 articles. The study details of the unavailable articles were obtained from 4 different articles.[5,6,14,15] Therefore, the current analysis included 40 patients (21 [52.5%] males and 19 [47.5%] females; ages, 7–93 years; mean ± SD, 54.0 ± 21.5 years). The age range of males was 29 to 87 years (mean ± SD, 57.5 ± 16.9 years) and that of females was 7 to 93 years (mean ± SD, 50.1 ± 25.0 years). The male:female ratio was 1:1. The external opening area of the fistula was reported for all patients, and the fistula opening was localized to the right hypochondrium in 11, the right flank in 4, the right thoracic wall in 4, the left hypochondrium in 3, the sternal area in 2, the inguinal region in 2, the periumbilical region in 2, the left flank in 2, and the left thoracic wall in 1 patient. Twenty-four (60%) patients had cysto-cutaneous fistulization (E granulosus); 10 (25%) had cutaneous fistulization (E multilocularis), 3 had cysto-cutaneo-bronchio-biliary fistulization, 2 had cysto-cutaneo-bronchial fistulization; and 1 had cutaneo-bronchial fistulization (E multilocularis). While 29 (72.5%) patients were diagnosed with E granulosis, 11 (27.5%) patients had E multilocularis that was detected by clinical, radiological, and/or histopathological examinations. The detailed clinical and demographic characteristics of the 40 patients with cutaneous fistulization/involvement of HD are summarized in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of 38 articles involving 40 patients published in medical literature between 1987 and 2016.

Table 1 (Continued).

Demographic and clinical characteristics of 38 articles involving 40 patients published in medical literature between 1987 and 2016.

3.2. Case report

A 56-year-old male patient was referred to our clinic for nausea, vomiting, and a swelling on the anterior abdominal wall. He had undergone surgery for a perforated peptic ulcer 15 years ago. A physical examination revealed hyperemia around the abdominal wall incision and a fascial defect at the abdominal midline. Abdominal US showed that a few of the lesions were consistent with HCs in both lobes of the liver and the spleen. The patient was examined with a panendoscope to differentially diagnose the dyspeptic complaints. The endoscopic examination revealed external compression of the gastric wall. The echinococcal indirect hemagglutination test was positive at a titer of 1:256. A contrast-enhanced abdominal CT scan showed 2 calcifying lesions consistent with HCs, the largest of which had a diameter of 5 cm, in the anterior and posterior segments of the right lobe of the liver. The other HC lesion was 11 × 10 cm and almost completely filled the left lobe of the liver. This HC was compressing the stomach, and was close to the anterior abdominal wall. Additionally, 2 more lesions resembling HCs, of which the larger had a 10-cm diameter, were detected in the spleen (Figs. 1 and 2). Surgery was scheduled, so the patient was administered two 400-mg doses of albendazole p.o. and a pneumococcal vaccine. Five days after the initial examination the patient presented to our emergency department with marked redness and discharge from the abdominal wall. A physical examination revealed a clear fluid discharge from a 1.5-cm opening. After local anesthesia, the orifice was dilated and daughter vesicles and a large volume of HC fluid were drained (Fig. 3). The patient underwent surgery the next day. The cyst that almost completely filled the left lobe of the liver and fistulized to the epigastrium was excised completely. Then, the cyst in the right lobe was drained with a partial cystectomy + omentopexy, and a splenectomy was performed. The fascia was closed, the incision was debrided, and the wound was allowed to heal. Albendazole was started 3 days after surgery; the patient received 4 cycles. No recurrences were detected at the 6-month follow-up visit.

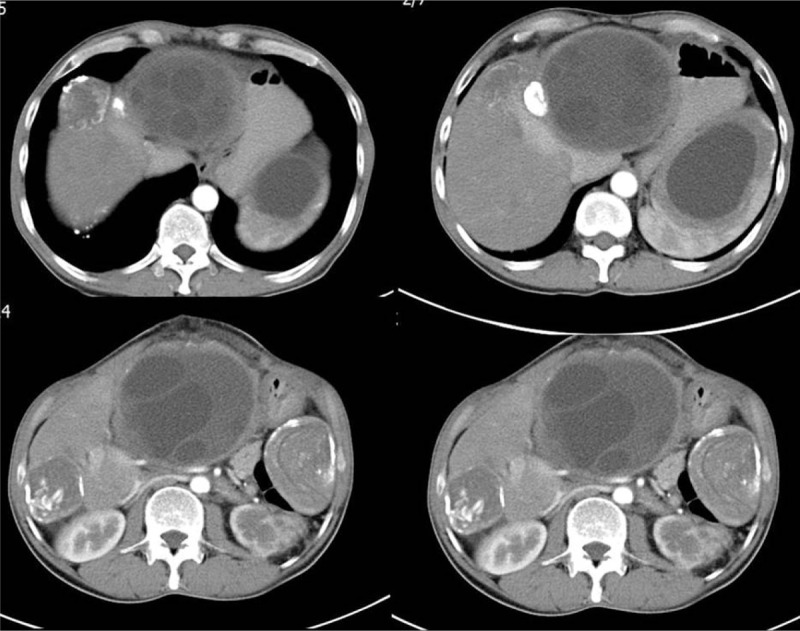

Figure 1.

Axial abdominal computed tomography images obtained from different sections after injecting contrast material. A lesion consistent with a stage III hydatid cyst is seen in the posterior segment of the right liver lobe and another lesion consistent with a stage V hydatid cyst is seen in the anterior segment of the right liver lobe. Lesions consistent with stage I and stage V hydatid cysts are seen in the upper and lower poles of the spleen, respectively.

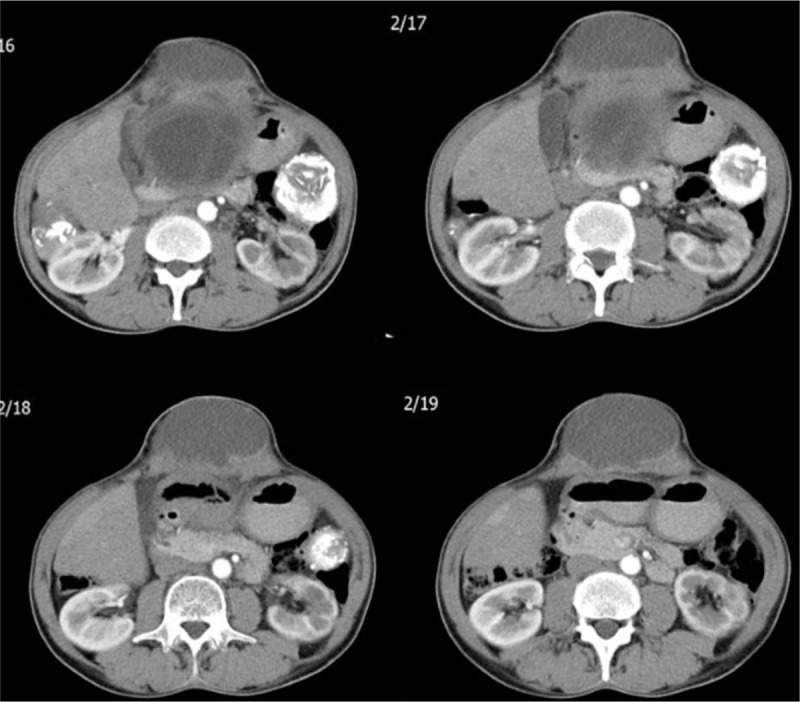

Figure 2.

Sequential abdominal computed tomography images taken after injecting contrast material. A lesion consistent with a hydatid cyst is seen starting from segment 3 of the left liver lobe and protruding into the anterior abdominal wall.

Figure 3.

Physical examination shows a clear fluid discharge and daughter vesicles originating from an opening in the abdominal wall.

4. Discussion

HD is a serious public health problem that is prevalent in many regions around the world where live animal husbandry is the primary source of living. Turkey is geographically part of the Middle East and Mediterranean regions and is one of several countries where HC disease is endemic. Humans have no role in the biological cycle of the causative organism and are accidentally infected after ingesting Echinococcus eggs in dog feces. Larvae are released into the gastrointestinal tract after the ingested eggs rupture, penetrate the intestinal wall, and pass into the portal system to reside in the hepatic sinusoids. Small-sized larvae pass through the hepatic filtration system and reach the lungs. There, the majority of larvae are cleared by a second capillary filtration system. Those that go unfiltered can easily reach many organs and systems of the body. Considering this dissemination route, it is quite easy to understand why it primarily involves the liver (50–77%) and lungs (10–40%).[1,6]

Liver HD can remain asymptomatic for years. Most asymptomatic patients are incidentally diagnosed by radiological tests performed for other indications.[6] Sometimes, HD can increase the size of the liver and patients are diagnosed by a physical examination in which a palpable liver is detected. Clinical symptoms can vary greatly depending on the size, number, and localization of HCs, their anatomical relationship with adjacent organs, and compression of adjacent organs.[36]

The most common complications of HD include secondary infections (super-infected HCs), anaphylactic reactions, vascular compression (Budd–Chiari syndrome, portal hypertension, or portal vein thrombosis), biliary compression (obstructive jaundice or cholangitis), compression of adjacent structures (gastric outlet obstruction or duodenal compression), and internal or external rupture.[6,12] Internal rupture, also known as an internal perforation, is the most serious complication of HD. Rupture of HCs into the biliary tree, gastrointestinal tract, bronchi, pleural space, or peritoneal cavity is referred to as an internal rupture.[4] On the other hand, rupture into the external body surface is an external rupture, external perforation, or cutaneous fistulization. Cutaneous fistulization is a rare complication of HD involving many organs, including the liver.

HD follows several stages before reaching the abdominal or thoracic wall to develop into an external rupture. Stage I hydatid lesions protrude into the innermost muscular layer of the abdominal or thoracic wall. Stage II lesions pass beyond the muscular layer and protrude into subcutaneous soft tissue. Stage III is characterized by the passage of lesions into subcutaneous tissue and their fistulization in the skin, which is called an external rupture, external fistulization, or cutaneous fistula.

Clinical suspicion is the first and most important step in the diagnosis and management of complicated HD. Living in an endemic region and a history of HD are important clues for the diagnosis. Discharge of hydatid fluid or daughter vesicles from the external orifice of a fistula is a useful clinical sign in patients presenting with cutaneous fistulization. When clinical signs are used in combination with radiological tools and serological tests, the diagnosis can be easily made in almost all patients. A histopathological examination of the fluid discharged from the external orifice of a fistula can demonstrate the parasite itself and identify a superinfection, if present. US, CT, and MRI are the most commonly utilized radiological tools to diagnose cutaneous involvement and locate lesions causing complications of the HD. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC), and endosonography are the other invasive radiological methods used for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. The most useful radiological method for cutaneous manifestations of the disease is contrast-enhanced fistulography. This technique helps clinicians specify the extension of the fistula, the location and size of a fistulized lesion, and its relationship with bile ducts, bronchopleural structures, and the pelvicaliceal system. In the present study, 7 (17.5%) of the enrolled patients underwent fistulography in addition to other radiological examinations. Bresson-Hadni et al[30] reported that fistulography failed to show any connection between the fistula tract and the liver lesion. Prieto-Nieto et al[37] showed a connection between the fistula tract and bronchobiliary structures by fistulography in a patient who had undergone HC surgery years ago. Prieto-Nieto et al[37] reported that they filled the fistula tract with Tissucol, a biological fibrin glue, and successfully treated the patient. In conclusion, the success rate of fistulography for showing organ involvement of a cystocutaneous fistula is 85.7%. In the present case, we did not use fistulography due to discharge of boluses of daughter vesicles through the incision scar. However, fistulography can be performed under appropriate conditions in all cases with a narrow fistula orifice and an unclear diagnosis. We cannot provide a clear recommendation due to a lack of sufficient data on this subject.

The most commonly used serological tests for diagnosing complicated and noncomplicated HD and monitoring posttreatment recurrences are enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, indirect hemagglutination, serum immunoelectrophoresis, the complement fixation test, and immunofluorescence assay. Nineteen of 40 enrolled patients underwent various serological tests; 94.7% had a positive test result. Only 1 patient returned negative serology, although costal HD was shown histopathologically.

The most appropriate strategy to minimize recurrence in patients with complicated HD and cutaneous fistulization is to combine surgical and medical treatment modalities. A 2 to 4-week neoadjuvant medical treatment followed by elective surgery is the most appropriate approach for patients who are not in need of urgent surgical intervention. Surgical treatment includes en block resection of the primary hydatid lesions causing the complication, diseased skin region, and fistula tract. Radical options, such as pericystectomy, segmentectomy, and lobectomy, can be used to minimize recurrence. Adjuvant medical treatment is not necessary in patients treated with radical surgery. On the other hand, all daughter vesicles should be removed with the germinative membrane in patients treated conservatively, such as partial cystectomy or cystotomy, and medical treatment should be administered for 4 to 12 weeks after the surgery. Fascial defects formed on the abdominal or thoracic wall after resecting the skin, and the fistula tract should be closed primarily or using artificial graft material. Patients diagnosed with a superinfection or abscess should be treated with drainage and antibiotic therapy specific to the bacteria that grow in culture. The situation is somewhat more complicated in skin fistulae associated with an E alveolaris infection in which multiple cutaneous fistula orifices and multiple hepatic/thoracic lesions are present. These lesions should be resected with a 1-cm clean surgical border as if a tumor were present.[3,17] Regardless of the surgical method used, long-term medical treatment should be administered for E alveolaris after surgical resection.[3] In the present short literature review, adjuvant medical treatment was administered for 1 to 12 months in 60% of cases with cutaneous involvement. Four of the treated patients were diagnosed with an extensive E alveolaris infection and received long-term medical treatment without any surgical treatment. Reuter et al[27] reported favorable results administering amphotericin B in 2 cases with hepatic toxicity to benzimidazole. Four studies have reported using amphotericin B to treat E alveolaris and 3 of these were reported by Reuter et al.[27] The authors suggested using amphotericin B in cases intolerant or resistant to benzimidazole. In conclusion, we cannot make any solid recommendations for managing HD with cutaneous fistulization, as a limited number of such cases have been reported so far. This topic should be explored further in future studies.

4.1. Topic highlights

Cutaneous fistulization is a rare but serious complication of hydatid disease.

A preoperative diagnosis is quite challenging when no cyst material has been drained from the external os of a fistula tract.

Awareness is an important approach to hydatid disease and its complications.

Complicated hydatid disease should be considered in the differential diagnoses of patients presenting with cutaneous fistulization, particularly in regions where hydatid disease is endemic.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CT = computed tomography, Endo US = endosonography, ERCP = endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography, HC = hydatid cyst, HD = hydatid disease, IHA = indirect hemagglutination, MRI = magnetic resonance imaging, PAIR = puncture-aspiration-injection-reaspiration, PTC = percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography, US = ultrasonography.

ZSB and UA performed surgical procedure and patient management, SA and FD designed the literature review and organized the report; SA, ZSB, and FD collected the data; AS provided radiological information; SA wrote the paper.

This study was not supported financially and did not receive any kind of grants.

The authors have no have no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Mandolkar SD, Ramakanth B, Anil Kumar PL, et al. Cystocutaneous fistula of the left lobe of liver: an extremely rare presentation of hydatid liver cyst. Int Surg J 2015; 2:109–111. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jayant K, Agrawal S, Agarwal R, et al. Spontaneous external fistula: the rarest presentation of hydatid cyst. BMJ Case Rep 2014; 2014: pii: bcr2014203784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Juodeikis Z, Poskus T, Seinin D, et al. Echinococcus multilocularis infection of the liver presenting as abdominal wall fistula. BMJ Case Rep 2014; 2014: pii: bcr2014203769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sachdeva V, Singh SK, Sood V, et al. Cutaneous bronchobiliary fistula following laparotomy for ruptured hydatid cyst of the liver. Int Surg J 2014; 1:155–157. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kjossev KT, Teodosiev IL. Cutaneous fistula of liver echinococcal cyst previously misdiagnosed as fistulizated rib osteomyelitis. Trop Parasitol 2013; 3:161–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Korwar V, Subhas G, Gaddikeri P, et al. Hydatid disease presenting as cutaneous fistula: review of a rare clinical presentation. Int Surg 2011; 96:69–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gupta BB, Schangole S, Rnandagawali V, et al. Spontaneous cutaneous fistulization, eventration of right hemidiaphragm and invasion of the pericardial cavity by a liver hydatid cyst. Trop Gastroenterol 2013; 34:287–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bouassida M, Sassi S, Mighri MM, et al. Parietal complications of hydatid cyst of the liver. Report of two cases in Tunisia. Bull Soc Pathol Exot 2012; 105:259–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamid R, Shera AH, Bhat NA, et al. Hydatid cyst of liver: Spontaneous rupture and cystocutaneous fistula formation in a child. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg 2012; 17:73–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ben Ameur H, Trigui A, Boujelbene S, et al. Cutaneous fistula due to hydatid cyst of the liver. Ann Dermatol Venereol 2012; 139:292–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Lavaissiere M, Voronca C, Ranz I, et al. Pelvic hydatid cyst: differential diagnosis with a bacterial abscess with cutaneous fistula. Bull Soc Pathol Exot 2012; 105:256–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lacetera V, Galosi AB, Quaresima L, et al. Isolated hydatid cyst of the kidney. Urologia 2012; 79 suppl 19:67–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA Statement. Open Med 2009; 3:e123–e130. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daldoul S. Spontaneous cutaneous fistula of hydatid liver cysts. Ann Dermatol Venereol 2015; 142:736–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ambo M, Adachi K, Ohkawara A. Postoperative alveolar hydatid disease with cutaneous-subcutaneous involvement. J Dermatol 1999; 26:343–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramia Angel JM, de la Plaza R, Quinones Sampedro JE, et al. Hydatid cystocutaneous fistula. Cir Esp 2011; 89:189–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmoldt S, Bruns CJ, Rentsch M, et al. Skin fistulization associated with extensive alveolar echinococcosis. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 2010; 104:175–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chafik A, Benjelloun A, El Khadir A, et al. Hydatid cyst of the rib: a new case and review of the literature. Case Rep Med 2009; 2009:817205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yakan S, Yildirim M, Coker A. Spontaneous cutaneous fistula of infected liver hydatid cyst. Turk J Gastroenterol 2009; 20:299–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ali AA, Sall I, El Kaoui H, et al. Cutaneous fistula of a liver hydatid cyst. Presse Med 2009; 38:e27–e28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Onat S, Avci A, Ulku R, et al. Spontaneous cyst-cutaneous fistula caused by pulmonary hydatid cyst: an extremely rare case. Dicle Med J 2008; 35:280–281. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Florea M, Barbu ST, Crisan M, et al. Spontaneous external fistula of a hydatid liver cyst in a diabetic patient. Chirurgia (Bucur) 2008; 103:695–698. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kismet K, Ozcan AH, Sabuncuoglu MZ, et al. A rare case: spontaneous cutaneous fistula of infected splenic hydatid cyst. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12:2633–2635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sakorafas GH, Stafyla V, Kassaras G. Spontaneous cystcutaneous fistula: an extremely rare presentation of hydatid liver cyst. Am J Surg 2006; 192:205–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bastid C, Pirro N, Sahel J. Cutaneous fistulation of a liver hydatid cyst. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 2005; 29:748–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grigy-Guillaumot C, Yzet T, Flamant M, et al. Cutaneous fistulization of a liver hydatid cyst. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 2004; 28:819–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reuter S, Buck A, Grebe O, et al. Salvage treatment with amphotericin B in progressive human alveolar echinococcosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2003; 47:3586–3591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Selmi M, Kharrat MM, Larbi N, et al. Communication of an hydatid cyst of the liver with the skin and the biliary tract and bronchi. Ann Chir 2001; 126:595–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harandou M, el Idrissi F, Alaziz S, et al. Spontaneous cutaneous cysto-hepato-bronchial fistula caused by a hydatid cyst. Apropos of a case. J Chir (Paris) 1997; 134:31–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bresson-Hadni S, Humbert P, Paintaud G, et al. Skin localization of alveolar echinococcosis of the liver. J Am Acad Dermatol 1996; 34 (5 Pt 2):873–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berthet B, Assadourian R. Hydatid cyst of the liver disclosed by metastatic subcutaneous localization. Presse Med 1992; 21:952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Golematis BC, Karkanias GG, Sakorafas GH, et al. Cutaneous fistula of hydatid cyst of the liver. J Chir 1991; 128:439–440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tschudi K, Ammann R. Recurrent chest wall abscess. Result of a probable percutaneous infection with Echinococcus multilocularis following a dormouse bite. Schweiz Med Wochenschr 1988; 118:1011–1015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kehila M, Allegue M, Abdesslem M, et al. Spontaneous cutaneous-cystic-hepatic-bronchial fistula due to an hydatid cyst. Tunisie Med 1987; 65:267–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Virgilio E, Mercantini P, Tarantino G, et al. Broncho-hepato-cutaneous fistula of hydatid origin. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2015; 16:358–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Akay S, Erkan N, Yildirim M, et al. Development of a cutaneous fistula following hepatic cystic echinococcosis. Springerplus 2015; 4:538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prieto-Nieto MI, Perez-Robledo JP, Alvarez-Luque A, et al. Cutaneous bronchobiliary fistula treated with Tissucol sealant. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2011; 34 suppl 2:S232–S235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martin-Perez E, Gomez J, Rubio I, et al. Spontaneous cutaneous fistula of a liver hydatid cyst: a rare complication of hydatid disease. Surg Chronicles 2011; 16:171–173. [Google Scholar]

- 39.El Ammari J, Mellas S, El Fassi MJ, et al. Hydatid cyst of the kidney fistulised at the skin-case report. J Maroc Urol 2008; 9:38–41. [Google Scholar]