Abstract

Background:

Though accumulated evidence proved that laparoscopic major hepatectomy was technically feasible, it remains a challenging procedure and is limited to highly specialized centers. Paragonimiasis is one of the most important food-borne parasitic zoonoses caused by the trematode of the genus Paragonimus. Although hepatic paragonimiasis is rare, the previous studies had investigated hepatic paragonimiasis from different perspectives. However, the safety and feasibility of laparoscopic major hepatectomy for hepatic paragonimiasis have not yet been reported in the literature.

Methods:

We here present 2 cases of hepatic paragonimiasis at the deep parts of the liver with treatment by laparoscopic major hepatectomy. One case is a 32-year-old male patient who was admitted to the hospital due to upper abdominal discomfort without fever for 1 month. The clinical imaging revealed that there was a lesion about 5.9 × 3.7 cm in the boundary of right anterior lobe and right posterior lobe of the liver with rim enhancement and tract-like nonenhanced areas. The other one is a 62-year-old female patient who was referred to the hospital for 1 month of right upper abdominal pain and fever. The ultrasonography showed that there was a huge hypoechoic mass (about 10.8 × 6.3 cm) in middle lobe of the liver with tract-like nonenhanced areas. Both patients were from an endemic area of paragonimiasis and the proportion of eosinophil in the second case was increased.

Results:

The preoperative diagnosis of the first case was ambiguous and the hepatic paragonimiasis was considered for the second case. The first case underwent laparoscopic extended right posterior lobe hepatectomy and the other case underwent laparoscopic extended left hemihepatectomy. Both operations went very well and the operation times for the 2 cases were 275 minutes and 310 minutes, respectively. The 2 patients’ postoperative recovery was smooth without major postoperative complications (such as, bleeding, bile leakage, and liver failure). Moreover, the 2 patients were discharged on the 6th day and 7th day after surgery, respectively. The postoperative histopathological examination manifested hepatic paragonimiasis in both patients.

Conclusion:

This study suggests that the laparoscopic approach may be safe and technically feasible for hepatic paragonimiasis.

Keywords: hepatic paragonimiasis, laparoscopic hepatectomy, feasibility

1. Introduction

Laparoscopic hepatectomy (LH) has been widely performed for patients with different benign and malignancy liver diseases.[1–5] A recent study showed that LH had been increasing in frequency with over 9000 LHs done worldwide.[6] Although laparoscopic major hepatectomy has been proved to be technically feasible by accumulated evidence, laparoscopic right hepatectomy remains a challenging procedure and is limited to highly specialized centers.[7] From the world review of 2804 LHs reported in 2009,[2] laparoscopic major hepatectomy accounted for only 16.6% (466 of 2804) of the total cases. Paragonimiasis is a parasitic infestation caused by the lung fluke and there are only 2 species, Paragonimus skrjabini and P. westermani, that existed in the Sichuan Province of China as reported.[8] Although hepatic paragonimiasis is rare, there are some reports[9–12] that investigated hepatic paragonimiasis from different perspectives. However, to the best of our knowledge, LH for hepatic paragonimiasis has not yet been reported in the literature. Therefore, we report 2 cases of hepatic paragonimiasis at the deep parts of the liver with treatment by laparoscopic major hepatectomy.

2. Case report

2.1. Patient 1

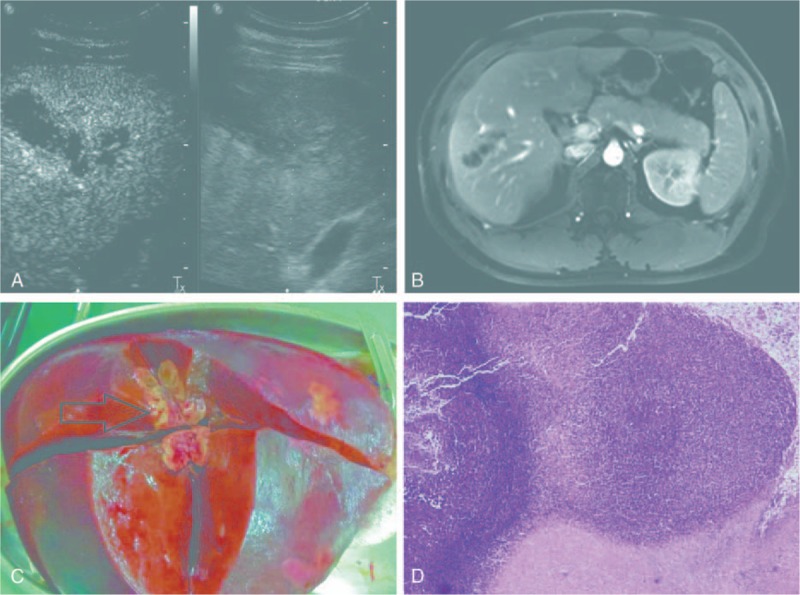

A 32-year-old male patient was admitted to our hospital due to upper abdominal discomfort without fever for 1 month. Peripheral blood examination revealed 8.0% eosinophils (0 < normal range <8.0%) with white blood cell count in the normal range. Tumor markers including alpha fetoprotein (AFP), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), CA125, and CA19-9 were all normal. Preoperative liver functional was Child A and the preoperative indocyanine green R15 clearance was 2.1%. The patient's chest X-ray was normal. Ultrasonography revealed that there was a mass (about 5.9 × 3.7 cm) in the boundary of right anterior lobe and right posterior lobe of the liver with rim enhancement and tract-like nonenhanced areas, eosinophilic abscess (Fig. 1A). Abdominal enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed there was a cyst-solid mixed lesion in the right lobe of the liver with intrahepatic bile duct dilatation and chronic cholangitis with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma was suspected (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

(A) Ultrasonographic images for case one showed rim enhancement and tract-like nonenhanced areas (yellow arrow head). (B) Abdominal enhanced magnetic resonance imaging showed there was a cyst-solid mixed lesion (white arrow head) in the right lobe of the liver. (C) Surgical specimen of the liver shows the lesion (black arrow head) was located in the boundary of right anterior lobe and right posterior lobe of the liver. (D) Pathological findings showed coagulative necrosis within the lesion, surrounded by infiltration of a large number of epithelioid cells (H&E stain, ×40).

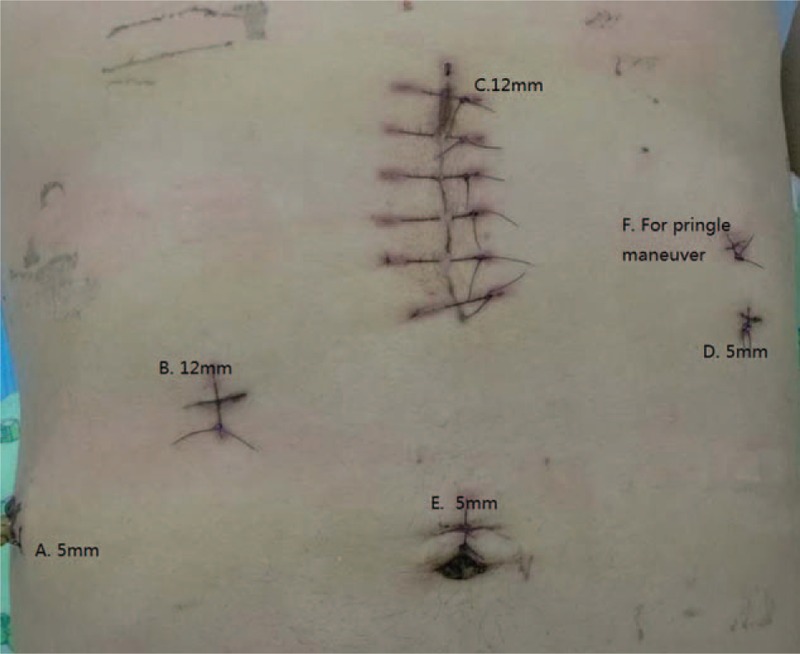

Our technique for LH was described previously.[13] Briefly, carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum was established with use of a veress needle and pressure was maintained at 13 mm Hg. The patient was placed in the left semidecubitus position with the right side elevated approximately 30°. Three 12-mm and two 5-mm trocars (Ethicon Endo-Surgery Inc., Cincinnati, OH) were usually inserted (Fig. 2). Laparoscopic ultrasound was used to identify the lesion and guide resection in this case. Because the mass was located in the boundary of right anterior lobe and right posterior lobe of the central part of liver, we decided to perform laparoscopic extended right posterior lobe hepatectomy (nonanatomical right hemihepatectomy reserved partial segment V, segment VIII, and reserved hepatic pedicle of the right anterior lobe). Firstly, we used ultrasonic shears to transect the ligamentum teres hepatis, falciform ligament, right coronary ligament, right triangle ligament, and right hepatorenal ligament, and made the whole right lobe of liver mobilizable. The right adrenal gland was completely dissociated by a LigaSure (a 5-mm vessel sealing system, Covidien Inc., Boulder, CO). After cholecystectomy was completed, we started to transect liver parenchymal. The superficial part of the liver was dissected by ultrasonic shears, and the deeper tissue was dissected by laparoscopic ultrasonic aspirator (CUSA Excel, Valleylab, CO) and LigaSure with intermittent pringle maneuver. The hepatic vein branches of segment VI and VII were dissected and clamped by Hem-o-lok and the transection line was far from the right side of middle hepatic vein. The hepatic pedicle tissue of the right posterior lobe was transected by a laparoscopic linear stapler with 60-mm white cartridge (Endopath Endocutter, Ethicon Endo-Surgery Inc.).

Figure 2.

Port placements.

During the intraoperative period, we were unable to see the mass in the liver by visual inspection except for laparoscopic ultrasound examination. When taking out the specimen from linea alba of upper abdominal wall with a 7-cm incision, we saw the mass after the specimen was longitudinally cut (Fig. 1C). This operation took 275 minutes and estimated blood loss was 200 mL. No intraoperative complications, such as air embolization, hepatic vein injury, oxygen saturation decreasing, and hypotension, were met. The patient's postoperative recovery was smooth without postoperative complications and was discharged on the 6th day after surgery. Postoperative histopathological examination showed coagulative necrosis within the lesion, surrounded by infiltration of a large number of epithelioid cells (Fig. 1D) and the diagnosis was hepatic paragonimiasis. He also received a standard course of praziquantel 25 mg/kg tid given orally for 2 days and recovered well.

2.2. Patient 2

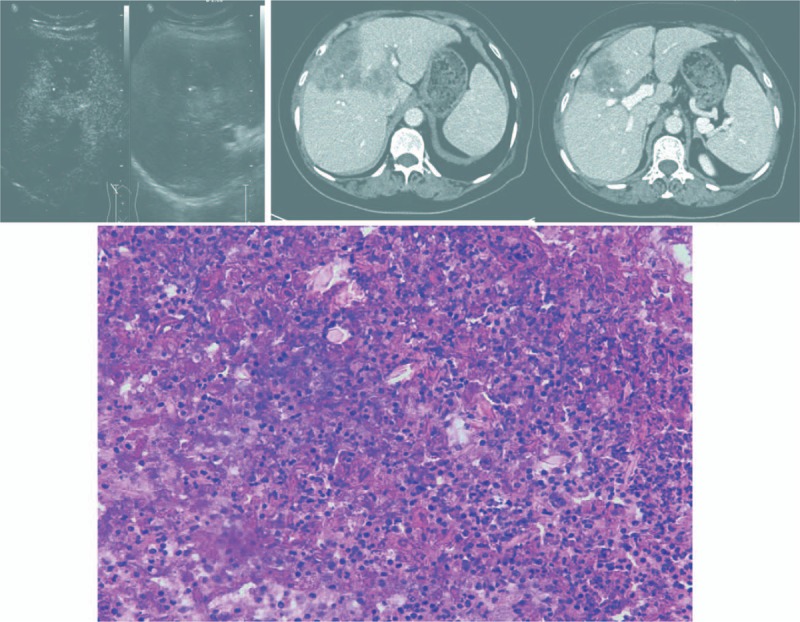

A 62-year-old female patient, with a history of diabetes mellitus for 2 years, was referred to our hospital for 1 month of right upper abdominal pain and fever. Initial peripheral blood examination revealed her white blood cell count was 6.55 × 109/L with an eosinophil proportion of 32.8% (reference range, 0.4% to 8.0%) and an eosinophil count of 2.15 × 109/L (reference range, 0.02 × 109 to 0.52 × 109/L). The levels of AFP, CEA, CA125, and CA19-9 were all normal. Moreover, the patient's chest X-ray was normal. Ultrasonography showed that there was a huge hypoechoic mass (about 10.8 × 6.3 cm) in middle lobe of the liver with tract-like nonenhanced areas (Fig. 3A). Abdominal enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan showed that there were 2 lesions in the middle lobe of the liver with rim enhancement after intravenous injection of contrast material and liver abscess were suspected. The size for segment VIII and IV were estimated to be about 7.6 × 5.3 cm and 4.7 × 4.3 cm in diameter, respectively (Fig. 3B, C). The preoperative diagnosis was considered for hepatic paragonimiasis.

Figure 3.

(A) Ultrasonographic images for the second patient showed tract-like nonenhanced areas (yellow arrow head). (B, C) Abdominal enhanced computed tomography scan images at portal vein stage showed that there were 2 lesions (white arrow head) in the middle lobe of the liver with rim enhancement after intravenous injection of contrast material. (B) The hepatic pedicle tissue of the left lobe (yellow triangle) was suspiciously invaded by the paragonimiasis. (C) The hepatic pedicle tissue of the right anterior lobe (yellow triangle) was also suspiciously invaded by the paragonimiasis (yellow arrow head). (D) Pathological findings showed track-like structures with eosinophilic abscess formation, numerous eosinophils, and Charcot–Leyden crystals (white arrow head) (H&E stain, ×400).

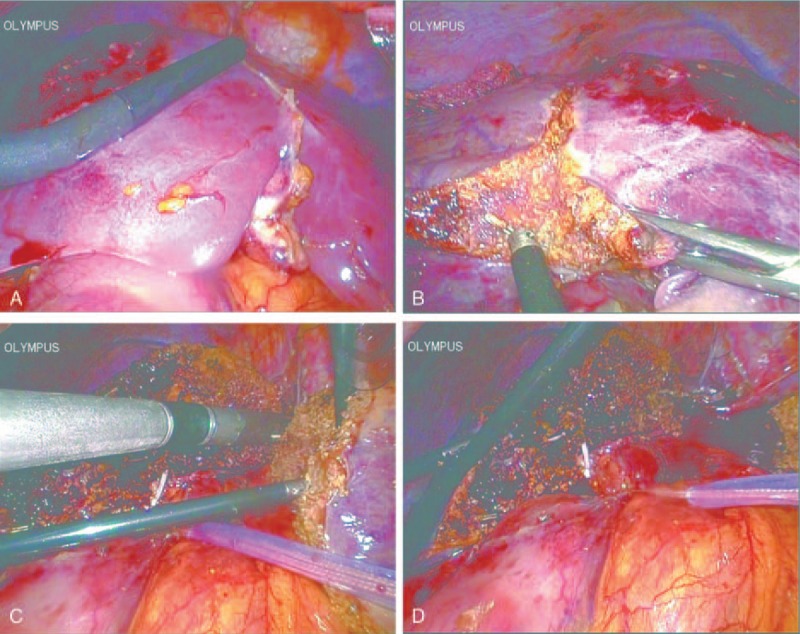

The patient underwent laparoscopic extended left hemihepatectomy. The operation procedure for the second patient was more or less the same as the first case. At first, laparoscopic ultrasound was used to confirm the mass and guide resection in this case (Fig. 4A). After the whole liver was mobilized by ultrasonic shears, we resected the gallbladder and prepared for liver resection. The superficial part of the liver was dissected by ultrasonic shears, and the deeper tissue was dissected by laparoscopic ultrasonic aspirator (CUSA Excel, Valleylab, CO) and LigaSure with intermittent pringle maneuver. The middle hepatic vein and left hepatic vein were transected by a laparoscopic linear stapler with 60-mm white cartridge (Endopath Endocutter, Ethicon Endo-Surgery Inc.). The hepatic pedicle tissue of the right anterior lobe and left lobe were also transected by the laparoscopic linear stapler with 60-mm white cartridge (Fig. 4B–D).

Figure 4.

Laparoscopic hepatectomy images for case two. (A) Laparoscopic ultrasound (yellow arrow head) was used to confirm the mass (white arrow head) and guide resection. (B) Liver parenchymal transection was started (white arrow head shows the paragonimiasis). (C) Laparoscopic linear stapler was used to transect left hepatic vein. (D) Liver parenchymal transection was finished.

During operation, the huge hypoechoic mass was intact without rupture. This operation took 310 minutes and estimated blood loss was 450 mL. No intraoperative complications, such as air embolization, hepatic vein injury, oxygen saturation decreasing, and hypotension, were met. The patient's postoperative recovery was smooth without postoperative complications and was discharged on the 7th day after surgery. Postoperative histopathological examination showed that track-like or sinus structures with eosinophilic abscess formation, numerous eosinophils, and Charcot–Leyden crystals (Fig. 3D) were seen in the lesions and the diagnosis was hepatic paragonimiasis. She also received a standard course of praziquantel and recovered well.

2.3. Ethics statement

All clinical investigations were in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was obtained from the Committee of Ethics in West China Hospital of Sichuan University. A written informed consent was obtained from each subject involved in the study.

3. Discussion

Paragonimiasis, also known as lung fluke infection, is one of the most important food-borne parasitic zoonoses caused by the trematode of the genus Paragonimus, which is endemic in many parts of Asia.[14] The Sichuan Province of China is an endemic area of paragonimiasis where only 2 species, P. skrjabini and P. westermani, were reported.[8] Lung fluke infection can be acquired by ingesting infective metacercaria encysted in the muscle and viscera of crayfish and freshwater crab. The ingested metacercariae excyst in the upper intestine and penetrate into the abdominal cavity. And then, they migrate through the diaphragm, pleural cavity, and finally reach the lungs where they mature to adults.[15] During the journey from the intestine to the lung, the juvenile worms often cause damage to the liver capsule and parenchyma.[16,17] Hepatic paragonimiasis can be divided into 3 types, one type involving only the liver, one type involving only the biliary system, and the other involving both the liver and the biliary system.[18] In the present case one, only biliary system was involved; while both the liver and the biliary system were involved in the second patient.

Because the previous definitive diagnosis of paragonimiasis is mainly based on the presence of eggs in patients’ sputum or feces, or flukes in histological specimens;[9] it is difficult to establish an accurate diagnosis of extrapulmonary paragonimus preoperatively (eggs usually cannot be found in most of the extra-lung lesions). Therefore, hepatic paragonimiasis often appears as a mass that should be differentiated from other cancerous lesions. In recent years, some imaging studies have increased the confidence of the clinical diagnosis for hepatic paragonimiasis. Such as, Lu et al[9] investigated the imaging features of hepatic paragonimiasis on contrast-enhanced ultrasonography (CEUS) and found that subcapsular location, hypoechogenicity, rim enhancement, and tract-like nonenhanced areas could be seen as the main CEUS features of hepatic paragonimiasis. Moreover, Li et al[17] showed that peripherally distributed lesions, mutually connected cysts with tortuous tract formation, and tubular enhancement could be seen as the main CT features. The first patient showed a mass in the liver with rim enhancement and tract-like nonenhanced areas in the CEUS, which was a characteristic CEUS imaging for hepatic paragonimiasis. In addition, this patient was from Sichuan Province, which was an endemic region for paragonimiasis, and had a history of eating raw crayfish at times. However, the abdominal enhanced MRI showed there was a cyst-solid mixed lesion in the right lobe of the liver with intrahepatic bile duct dilatation and chronic cholangitis with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma was suspected. Meanwhile, preoperative serum eosinophil percentage of 8.0% was at the upper limit of normal range and eosinophils cell count was in the normal range. Although the normal level of CA19-9 did not support the diagnosis of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, it was still extremely difficult to make a correct diagnosis without histopathological examinations. Eventually, the postoperative histopathological examination manifested hepatic paragonimiasis.

Oral administration of deworming medicine such as praziquantel could be effective in some patients, especially in those with small lesion in the liver; however, the standard course of praziquantel was ineffective for some cases and liver surgery was recommended.[16,19] Therefore, liver resection may be a good choice for hepatic paragonimiasis in some cases, especially in those with large mass in the liver, those with ambiguous preoperative diagnosis, and those with ineffective drug treatment. LH has been widely performed for patients with different benign and malignancy liver diseases due to its advantages of minimal invasiveness, decreased postoperative morbidity, and shorter length of stay compared with open liver resection.[2,6] Although a lot of LHs had been reported, laparoscopic major hepatectomy accounted for only a small part of the total cases.[2] It indicated that the operating difficulty of laparoscopic major hepatectomy was apparent. To our knowledge, this is the first report in the literature of laparoscopic major hepatectomy for hepatic paragonimiasis. Both of the patients in the present study had underwent laparoscopic major hepatectomy and recovered well. Although the lesion was not large enough in the first case, we performed LH because the preoperative diagnosis was not clear. Because the lesion was located in the boundary of right anterior lobe and right posterior lobe of the central part of liver, we performed laparoscopic extended right posterior lobe hepatectomy for this case. The second patient underwent laparoscopic extended left hemihepatectomy because the hepatic pedicle tissue of the right anterior lobe and left lobe were suspiciously invaded by the paragonimiasis from the preoperative CT imaging. We must be very careful with surgical technique and operation when LH is used for hepatic paragonimiasis because the mass in such patients is solid-cystic and prone to rupture with improper operative procedures. If the mass in such patients is ruptured during surgery, there is a potential risk for occurrence of paragonimiasis spread and anaphylactic shock. Although the mass in the second patient was huge and near to the liver capsule, the huge mass was intact without rupture during the surgery.

One limitation of this study was that oral administration of deworming medicine such as praziquantel was not given in the 2 cases before surgery. Drug therapy is the first choice for most parasite diseases, and even in combination with surgery it has a good efficacy. Moreover, preoperative oral administration of praziquantel may be useful to avoid anaphylactic shock if the mass was accidentally opened while dissection during the surgery. One reason for this negligence was that the preoperative diagnosis was ambiguous in the first case. We considered that the empirical use of praziquantel to avoid anaphylactic shock was necessary in cases of suspected hydatid cyst if we were not sure of the diagnoses because Sichuan Province was an endemic area of paragonimiasis.

In summary, we firstly presented 2 cases of hepatic paragonimiasis with treatment by laparoscopic major hepatectomy and found LH for hepatic paragonimiasis was safe and technically feasible with skilled laparoscopic technique. Further observation of the method with a large sample size would be necessary in clinical practice to evaluate its therapeutic effects for hepatic paragonimiasis.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: AFP = alpha fetoprotein, CA19-9 = carbohydrate antigen, CEA = carcinoembryonic antigen, CEUS = contrast-enhanced ultrasonography, CT = computed tomography, LH = laparoscopic hepatectomy, MRI = magnetic resonance imaging.

The authors have no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Cherqui D, Husson E, Hammoud R, et al. Laparoscopic liver resections: a feasibility study in 30 patients. Ann Surg 2000; 232:753–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nguyen KT, Gamblin TC, Geller DA. World review of laparoscopic liver resection-2,804 patients. Ann Surg 2009; 250:831–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reddy SK, Tsung A, Geller DA. Laparoscopic liver resection. World J Surg 2011; 35:1478–1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kazaryan AM, Marangos IP, Røsok BI, et al. Laparoscopic resection of colorectal liver metastases: surgical and long-term oncologic outcome. Ann Surg 2010; 252:1005–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tranchart H, Di Giuro G, Lainas P, et al. Laparoscopic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: a matched-pair comparative study. Surg Endosc 2010; 24:1170–1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ciria R, Cherqui D, Geller DA, et al. Comparative short-term benefits of laparoscopic liver resection: 9,000 cases and climbing. Ann Surg 2016; 263:761–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cai L, Wei F, Yu Y, et al. Laparoscopic right hepatectomy by the caudal approach versus conventional approach: a comparative study. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 2016; Apr 29. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu X, Feng R, Zheng Z, et al. Hepatic damage in experimental and clinical paragonimiasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1982; 31:1148–1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu Q, Ling WW, Ma L, et al. Contrast-enhanced ultrasonographic findings of hepatic paragonimiasis. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19:2087–2091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cao WG, Qiu BA. Radiofrequency ablation of hepatic paragonimiasis: a case report. Chin Med Sci J 2012; 27:57–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li XM, Yu JQ, He D, et al. CT evaluation of hepatic paragonimiasis with simultaneous duodenal or splenic involvement. Clin Imaging 2012; 36:394–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yao A, Hammond N, Alasadi R, et al. Central hepatic involvement in paragonimiasis: appearance on CT and MRI. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2006; 187:W236–W237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li H, Wei Y, Li B, et al. The first case of total laparoscopic living donor right hemihepatectomy in mainland China and literature review. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2016; 26:172–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh TS, Sugiyama H, Rangsiruji A. Paragonimus and paragonimiasis in India. Indian J Med Res 2012; 136:192–204. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Braunwald E, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, et al. Harrison's Principle of Internal Medicine. Chapter 222. 15th ed.2001; New York: McGraw Hill, 1242–1248. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yokogawa M. Paragonimus and paragonimiasis. Adv Parasitol 1965; 3:99–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li XM, Yu JQ, Yang ZG, et al. Correlations between MDCT features and clinicopathological findings of hepatic paragonimiasis. Eur J Radiol 2012; 81:e421–e425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Beers B, Pringot J, Geubel A, et al. Hepatobiliary fascioliasis: noninvasive imaging findings. Radiology 1990; 174:809–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Q, Wei F, Liu WS, et al. Paragonimiasis: an important food-borne zoonosis in China. Trends Parasitol 2008; 24:318–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]