Abstract

Asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are common diseases which cause patients and society considerable difficulties. These are costly diseases which cause substantial morbidity and death. Health care policy makers have made improving outcomes in asthma and COPD a priority. Application of guideline recommended approaches to asthma and COPD care in the real-life setting has been emphasized but outcomes have not improved. Failure to improve outcomes may not be because of inconsistent applications of guideline recommendations, but rather because there are difficulties implementing the Expert Panel Report III (EPR 3) method for categorizing asthma severity and the Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) method for diagnosing COPD. As these serve as the foundation for treatment recommendations for these diseases, alternative approaches should be considered for categorizing asthma severity and identifying COPD patients. Claims-based algorithms provide an intriguing option for identifying persistent asthma patients and symptomatic COPD patients in administrative databases. These methods could be used as the basis for pragmatic research, both retrospective and prospective, on assessing outcomes of guideline recommended treatment approaches in asthma and COPD. Important questions urgently need to be answered about how guideline recommended approaches regarding use of long-acting inhaled β-agonist/inhaled corticosteroid (LABA/ICS) in asthma and long-acting inhaled anti-muscarinic agent (LAMA) and LABA/ICS in COPD affect outcomes in real-life situations.

Keywords: asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pragmatic research

Introduction

Asthma affects more than 25 million Americans, about 10% of the childhood population and 8% of adults.1 In the US more than 5% of adults have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).2 About 12 million Americans have been diagnosed with COPD3 and an additional 12 million Americans probably have undiagnosed COPD. Both asthma and COPD generate huge direct and indirect health care costs.2,4 Although the mortality rate associated with asthma is fortunately low,1 the death rate attributed to COPD is high.5 These sobering statistics have led to concerted efforts by health care policy makers to improve overall care for asthma and COPD. The most important initiative intended to advance care in asthma and COPD has been the development of formally structured clinical practice guidelines for aiding in the diagnosis and management of these diseases.2,6–8 Despite the widespread dissemination of clinical practice guidelines for asthma and COPD, there has been little evidence of improved outcomes. Population-based surveys have shown no change in the need for asthma-related acute care interventions, such as emergency department visits and hospitalizations, over the past decade.9,10 Deaths due to COPD are increasing.5 Health care policy makers have responded to these disappointing findings by suggesting that health care practitioners might not be adhering to treatment approaches recommended in clinical practice guidelines (also known as “best practices”). To more effectively align actual clinical practice with “best practices”, there has been a call in the US for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to develop performance measures in COPD. This would be a first step towards developing financial incentives, such as pay-for-performance, to reward health care providers (ie, those certified or licensed to practice medicine) who provide care in accordance with guidelines.11 Pay- for-performance metrics have already been implemented as a method to improve quality of care in asthma.12,13

Improving outcomes in asthma and COPD through more consistent application of recommendations in clinical practice guidelines, even through the use of financial incentives, rests on the critical assumption that following these recommendations will improve outcomes. Unfortunately, the available clinical research in asthma and COPD might not generally apply to assessing outcomes in real-life because this literature is heavily weighted toward either mechanistic studies or clinical trials supporting pharmaceutical products. Furthermore, more than 90% of asthma and COPD patients probably would not qualify for inclusion in typical asthma and COPD clinical trials.14,15 An alternative approach to addressing how recommendations in clinical practice guidelines might affect outcomes in typical asthma and COPD patients being managed in real-life would be to use pragmatic study designs. Pragmatic trials evaluate how interventions directly pertinent to patient care affect clinically relevant outcomes in real-world practice. They use broad eligibility criteria to ensure that patients entered into these trials reflect the full spectrum of disease. Pragmatic study methods merge seamlessly into usual clinical care rather than becoming artificial constructs. To best understand how pragmatic research can be used to improve outcomes in these diseases, key aspects of management recommendations in asthma and COPD guidelines should be critically examined.

Asthma severity as the basis for initiating pharmacotherapy

Guidelines for asthma care rely on accurately categorizing severity prior to beginning treatment.6,7 In the stepped-care approach to treating asthma, more aggressive treatments are reserved for more severe disease to appropriately match the risks from drug treatment with the potential benefits. Methods for categorizing asthma severity have evolved from clinically intuitive approaches based on symptoms, short-acting inhaled β-agonist (SABA) use and lung function, as in the Expert Panel Report II (EPR 2), to the more complex approach oriented towards considering the domains of impairment and risk in the Expert Panel Report III (EPR 3).6,16 There are difficulties, though, with relying on methods in the EPR 2 and 3 for categorizing asthma severity.

Awareness and understanding of guidelines

An unconsidered, but limiting, factor for categorizing asthma severity is how well health care providers are aware of and understand guideline methods. In the mid-to late 1990s, there was generally poor adherence of asthma treatment with earlier versions of guidelines, possibly because health care providers were simply unaware of guideline recommendations.17 Over time, though, health care providers reported basing their asthma management more reliably on guideline recommendations.18 Although physicians might report that their care is adherent to guidelines, three examples demonstrate that health care providers do not understand guideline approaches to asthma severity categorization. The EPR 2 and 3 guidelines recommend that asthma severity categorization should only be applied to patients not receiving long-term controllers (Figure 1), but the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) guidelines point out that asthma severity classification is “often erroneously applied to patients already on treatment.”7 There are many examples of publications presenting results of asthma severity categorization which have been incorrectly reported in patients already on long-term controllers.19,20 Doerschug et al developed a 31-question, multiple-choice test to assess physician understanding of the EPR 2 recommendations for asthma diagnosis and care.21 This test was administered to asthma specialists, general internists, family physicians, and house staff. Asthma specialists, as expected, scored higher on this test than others. Overall, though, only about 60% of questions were answered correctly. Physicians had particular difficulty answering questions related to severity categorization, answering fewer than 50% of these correctly. Baker et al presented eight case summaries based on actual patients with childhood asthma to pediatric asthma specialists and asked them to categorize asthma severity using the EPR 2 approach.22 Agreement on asthma severity categorization for the 14 specialists who completed the survey questionnaire was poor. The EPR 2, published in 1997, contains a simpler approach to asthma severity categorization than the EPR 3.6,16 Undoubtedly, if health care providers were questioned about their understanding of asthma severity categorization using the more complicated EPR 3 methods, the results would have been worse.

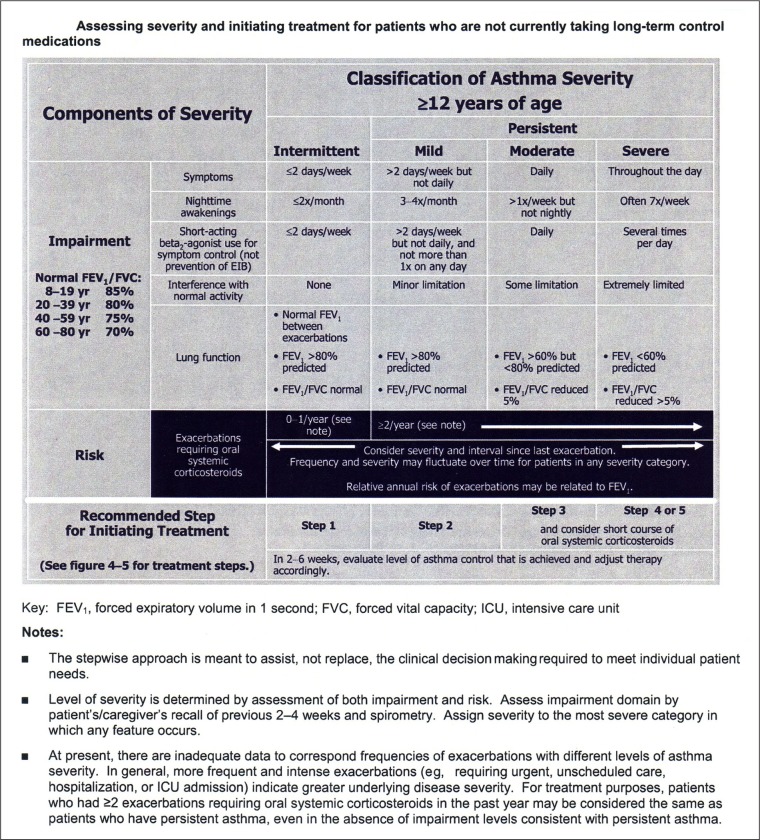

Figure 1.

The EPR 3 recommended approach to asthma severity categorization for asthma patients 12 years of age and older is complex.

Notes: Just below the title is the reminder, often not considered, that this severity categorization method should only be applied to patients not currently taking long-term controllers. The categorization method includes two domains. The impairment domain includes five variables which are both subjective and objective. The risk domain includes exacerbations. The worst ranking in any individual impairment and risk domain determines overall severity.6

Abbreviation: EPR 3, Expert Panel Report III.

Physician misunderstanding of the methods for asthma severity categorization is apparent in real life situations. Physician assessment of asthma severity often disagrees with categorization based on symptom reporting by patients and frequently is incorrect when compared to guideline methods. In a survey of 3468 asthma patients in a managed care organization23 patient-reported asthma symptoms were used to categorize their asthma severity using EPR 2 criteria. The patients’ primary care physicians were separately asked to estimate asthma severity, also using EPR 2 criteria. There was only 31% concordance between asthma severity categorization based on patient symptom reporting and physician estimates. The discordance was greatest in patients categorized by their physician as having mild disease. Over 80% of these patients had symptoms which should have placed them in the moderate or severe category. Incorrect categorization of asthma severity by physicians results in inappropriate treatment. Wolfenden et al determined asthma severity in 4005 asthma patients based on their symptoms.24 The patients’ physicians were also asked to categorize asthma severity using a method similar to the EPR 2 approach. Physicians both overestimated and underestimated asthma severity. In the 1565 patients categorized as having moderate asthma severity by their symptoms, most were categorized incorrectly by their physicians; physicians categorized 112 (7.2%) as having severe asthma and 824 (52.7%) as mild. Asthma treatment in these patients was based on the (often incorrect) physician asthma severity estimate. Consequently, patients were frequently over-treated and under-treated. These findings again demonstrate practical limitations in using the asthma severity categorization method proposed in the EPR 2 and 3 in real-life situations.

Airway inflammation

The severity categorization methods in EPR 2 and 3 make an important distinction between intermittent and persistent asthma.6 Regular use of a controller is recommended only in persistent asthma. The preferred controller for persistent asthma is an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) because this is the most effective class of drugs for controlling the airway inflammation typically found in asthma. The implication of this approach is that severity categorization will identify patients with airway inflammation treatable with an ICS. Vignola et al performed bronchoalveolar lavage and bronchial biopsies on 12 normal subjects, 24 patients with mild intermittent asthma, and 18 patients with persistent asthma.25 Evidence of airway inflammation, eg, lavage fluid eosinophilia, airway epithelial shedding, and increased basement membrane thickness, was found in the patients with mild intermittent asthma. Van den Toorn et al performed bronchial biopsies in 17 healthy control subjects, 18 patients with a history of asthma but in complete clinical remission and on no asthma medications, and 19 patients with active asthma.26 Surprisingly, airway inflammation, eg, presence of epithelial and subepithelial inflammatory mediators such as tryptase, chymase and major basic protein, airway epithelial shedding, and increased basement membrane thickness, was seen in the patients with asthma in remission (Figure 2). Although it is not clear that treatment of the airway inflammation in these patients would have been clinically justified, these studies show that patients with intermittent asthma, as determined by clinical severity categorization methods, may have airway inflammation.

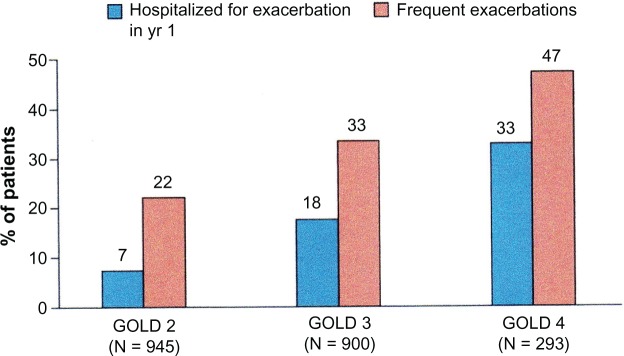

Figure 2.

(A) A normal bronchial biopsy from a patient without asthma compared with (B) a bronchial biopsy specimen from a patient with a history of asthma but in complete remission demonstrates epithelial shedding and extensive presence of α-major basic protein.

Note: Both of these findings indicate active ongoing airway inflammation. Reprinted with permission of the American Thoracic Society. Copyright © 2012 American Thoracic Society. LM Van den Toorn, SE Overbeek, JC de Jongste, K Leman, HC Hoogsteden, JB Prins/2001/Airway inflammation is present during clinical remission of atopic asthma/American Journal of Respiratory Critical Care Medicine/164/2107–2103. Official Journal of American Thoracic Society.26

Impairment

There are five variables in the impairment domain of the EPR 3 asthma severity categorization method (Figure 1). These variables include subjective, patient-reported symptoms and objective lung function measures. The scaling of the subjective variables is of uncertain clinical relevance. For example, a minor change in symptom frequency from symptoms two or fewer times per week to more than two times per week is the threshold differentiating intermittent from persistent. No allowance is made for possible confounding factors when assessing two of the subjective variables, daytime symptoms and interference with normal activity. In patients who have asthma and who are also obese, obesity has been recognized to have an independent effect on symptoms relevant to asthma control.27 Also unclear is how the weighting of a subjective variable against an objective one was determined, eg, daily symptoms are considered the equivalent of a forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) of 60%–80% predicted.

There is little information available on the relative roles the variables in the impairment domain play in ultimately categorizing asthma severity. In one of the few studies to address this issue, Colice et al categorized asthma severity using EPR 2 methods in 744 asthma patients not on ICS controllers who were about to enter clinical trials with a new pharmaceutical product.28 They found that 68.3% were categorized as having severe persistent asthma. Remarkably, they found that nocturnal symptoms were the most common determining factor for overall asthma severity categorization. Lung function determined final asthma severity categorization less often than SABA use. There was poor agreement among the variables in categorizing asthma severity for individual patients.

Impairment versus risk

The EPR 3 is a novel approach to asthma severity categorization because it includes two domains for assessment, impairment and risk for exacerbations. Although both domains include highly relevant clinical information for health care providers to consider in caring for asthma patients, it is not clear how health care providers should weigh the impairment and risk domains in deciding on categorization and ultimately treatment. For instance, a long-acting inhaled β-agonist (LABA) in combination with an ICS will improve variables in the impairment domain faster than increasing the dose of an ICS because of the acute bronchodilator effects of the LABA.29 However, increasing the dose of an ICS might have a greater long-term effect on reducing the risk of exacerbations than adding a LABA to a lower dose of ICS.30 Health care providers might choose a LABA/ICS specifically because they are more concerned about early symptom control than preventing later exacerbations.31

Asthma control

The GINA guidelines suggest basing severity on the intensity of treatment required to obtain control as an alternative approach to asthma severity categorization,7 but the variables used to assess asthma control are similar to those used for severity categorization. A more fundamental problem with this approach though, is understanding how well determining therapy based on the symptom-based methods recommended in guidelines will affect outcomes. Although this is the approach that clinicians use in practice for managing asthma, clinical trials addressing this issue are limited. A large, prospective, randomized, parallel group trial used EPR 2-based guideline methods for determining asthma control as an endpoint for adjusting pharmacotherapy over time.32 This study was designed to compare the effects of two pharmaceutical products and did not employ a non-guideline-based method as a comparison arm.

Guideline-based methods for determining asthma control have been compared against methods using measures of airway inflammation in conjunction with symptoms in guiding treatment. Green et al tested an approach to asthma management using eosinophilia in induced sputum together with a guideline method for assessing asthma control against using guideline methods only.33 Sont et al compared adding methacholine testing to determine bronchial hyperreactivity in conjunction with a guideline method for determining asthma treatment to simply relying on the guideline method.34 In both studies, adding a measure of airway inflammation resulted in significantly fewer exacerbations than simply relying on guideline methods (Figure 3). These studies suggest that tailoring treatment to asthma control, determined by guideline recommended methods, may not provide the best outcomes. However, the techniques used in those studies are time consuming and require considerable technical expertise to perform correctly. An easier to perform measure of airway inflammation, monitoring exhaled nitric oxide levels, has also been tested as a way to further improve asthma management over using guideline methods alone, but has not been shown to provide consistent benefit in either reducing exacerbations or improving symptom control.35–37

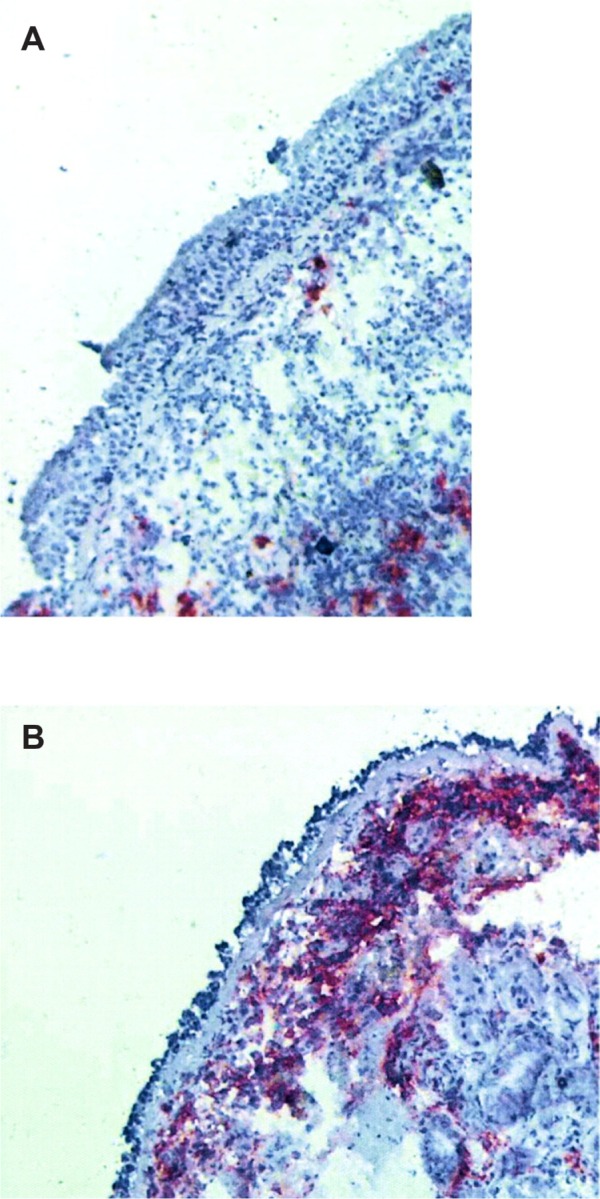

Figure 3.

(A) Cumulative severe exacerbations were significantly reduced when asthma treatment was determined by induced sputum eosinophilia used in conjunction with guideline methods (sputum management group) than guideline methods alone (BTS management group).33 (B) The cumulative incidence of mild first exacerbations was significantly lower when asthma therapy was adjusted based on methacholine testing used along with guideline methods (AHR-strategy) than guideline methods alone (Reference-strategy).34

Note: 3B is reprinted from Lancet, Vol 360, Issue 9347, Ruth H Green, Christopher E Brightling, Susan McKenna, Beverley Hargadon, Debbie Parker, Peter Bradding, Andrew J Wardlaw, Ian D Pavord, Asthma exacerbations and sputum eosinophil counts, Pages 1715–1721, Copyright 2002, with permission from Elsevier.

Abbreviations: AHR, airway hyperresponsiveness; BTS, British Thoracic Society.

Pragmatic research approaches to identifying asthma patients and categorizing severity

The current guideline-recommended approach to categorizing asthma severity is flawed. Health care providers are aware of guidelines, but objective evidence indicates that they do not understand how to use guideline recommended methods to categorize asthma severity. In clinical practice, inability to use guideline-recommended methods leads to incorrect treatment. Furthermore, there are difficulties with the structure of the guideline-recommended approach to asthma severity categorization. The clinical relevance of changes for some variables within the impairment domain is not certain. Health care providers are not provided clear guidance on how the impairment domain should be weighed against the risk domain in making treatment decisions. Using clinical measures of asthma control to guide treatment may not provide optimal outcomes when compared to approaches using markers of airway inflammation.

Pragmatic research may prove to be an important tool to use in developing methods for categorizing asthma severity which are accurate and easy to use for health care providers. Any approach for asthma severity categorization developed through pragmatic research should meet three criteria: it should be easily understandable for health care providers, appropriate for use in patients who are either on long-term controllers or only short-acting relievers, and applicable in both the clinic setting for the individual patient and the epidemiologic research arena for large populations. One approach to asthma severity categorization which has generated considerable interest is based on the Health Plan Employer Data and Information Set (HEDIS). The HEDIS was developed by the National Committee for Quality Assurance as a way to assess health plan quality of care performance. Use of the HEDIS approach for evaluating health care quality has been widely accepted by health plans and employers, as well as regulators, consumers, and public purchasers of health care.38 The HEDIS includes a component for identifying persistent asthma. Patients with persistent asthma are defined in HEDIS as those having four or more asthma medication dispensings, one or more acute inpatient or emergency department discharge(s) with a primary diagnosis of asthma, or four or more outpatient visits with asthma listed as one of the diagnoses, and two or more asthma medication dispensings.39

Initial work with the HEDIS method for identifying persistent asthma identified several potential problems with this approach. First, the HEDIS method misclassifies patients with intermittent asthma as having persistent asthma.38–40 To address this problem, Colice et al modified the HEDIS approach by adding another step which identifies persistent asthma based on SABA and oral corticosteroid use over a 1-year period.41,42 This approach has been useful in evaluating asthma costs in database analyses of large populations. As a further modification to the HEDIS method, asthma severity can be categorized into mild, moderate, and severe persistent groups based on patient pharmacotherapy. Second, claims-based algorithms for asthma severity have been criticized because they do not incorporate physiologic measures of lung function. Birnbaum et al have shown that adding spirometry results to the HEDIS claims-based algorithm modified by Colice et al did not appreciably affect asthma severity categorization.43 Third, because asthma is a variable disease over time, patients with persistent asthma identified during 1 year might not have persistent asthma the next year.44 Schatz and Zeiger have suggested that applying the HEDIS method over 2 years, rather than one, will adequately address this issue.45

Other approaches to assessing asthma control and outcomes involve administrative database review of medication use. Studies in health maintenance organizations have shown that records of SABA dispensing can provide an insight into risk for future acute asthma health care use, such as asthma-related emergency department visits and hospitalizations.46,47 The number of SABA canisters dispensed to a patient over time has also been found to be a useful indicator of asthma symptom control.47 An argument against relying on SABA dispensing records obtained from claims databases has been that some SABAs have been available over the counter, but these products will soon be removed from the market.48 An approach based on simply counting SABA dispensing has been refined to include dispensing records for long-acting controllers. If SABA use is considered along with controller use, a ratio of medication dispensing for long-term controllers and SABAs can be calculated. A ratio of at least 0.5, indicating that patients are preferentially filling their prescriptions for long-term controllers rather than relying on SABA use to relieve symptoms, has been associated with a lower likelihood for asthma exacerbations.49–51

Schatz and Zeiger suggested that, combined with information obtained from administrative databases on SABA and long-term controller use, and with results from asthma control questionnaires administered by telephone, the HEDIS method is a reasonable approach to evaluating quality of care in asthma management in large populations.45 There are two intriguing aspects of using claims data for asthma severity categorization and for predicting outcomes. Although these methods were developed for use in large populations, Schatz and Zeiger suggest it should also be applicable to group practices and individual patient care. Studies using Canadian administrative databases suggest that this approach can also be useful outside the US.52,53

Pragmatic research, asthma treatment, and asthma outcomes

Development of an approach that health care providers can use to accurately and easily identify patients with persistent asthma and categorize persistent asthma severity is an essential step towards addressing contentious issues regarding treatment recommendations in asthma guidelines. Busse has recently described a number of areas in which there are gaps in our understanding how to best treat asthma.54 However, it is clear that for the practicing clinician, the most contentious issue confronting them in treating asthma is understanding how combination LABA/ICS therapy affects outcomes in persistent asthma. The EPR 3 and GINA guidelines recommend use of LABA/ICS combination therapy in patients with moderate and severe persistent asthma because adding the LABA will allow use of lower doses of an ICS.6,7 These recommendations are consistent with findings from a recent Cochrane review showing that LABA/ICS therapy improves lung function and reduces symptoms to a significantly greater extent than ICS therapy alone.55 Long-term trials have shown that use of LABA/ICS therapy is associated with a greater likelihood of patients achieving asthma control than treatment with ICS alone.32

However, there are concerns about the use of LABA/ICS therapy. Retrospective studies of various insurance claim databases suggest that use of LABA/ICS combination products often do not conform to guideline recommendations; many patients treated with a LABA/ICS might have been managed with an ICS alone.56–58 As discussed above, this treatment approach might simply reflect the intent of health care providers to provide symptom relief as quickly as possible to their patients. Unfortunately, the benefits of reducing asthma impairment with a LABA/ICS might be counterbalanced by exacerbation risks. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has presented data showing that use of LABA/ICS might be associated with an increased rate of serious asthma exacerbations and asthma exacerbations resulting in death compared to use of ICS alone.59 Concerns about the safety of LABAs has led the FDA to change the labeling for LABA/ICS products and to restrict their long-term use. Industry sponsored reviews of safety databases compiled from clinical trials involving different LABA/ICS combination products have not shown evidence of a significant increase in asthma-related deaths with use of LABA/ICS.60,61 These analyses, though, might not have had sufficient sample size to adequately address this risk issue. Independent work has supported the FDA’s findings of a possible small but finite increased risk of asthma death with use of a LABA/ICS.62 The recent Cochrane review found that use of an increased dose of ICS was more effective at preventing exacerbations than LABA/ICS combination therapy.55

Recent pragmatic research has partly addressed the issue of outcomes with different asthma treatment approaches. Price et al compared the effect of choosing a leukotriene receptor antagonist rather than an ICS as initial therapy and adding a leukotriene receptor antagonist to an ICS rather than a LABA as add-on therapy.63 In contrast to guideline recommendations, patients treated with a leukotriene receptor antagonist had outcomes similar to those treated with an ICS initially or with a LABA as additional therapy. Important aspects of the approach used in this study were that patients were managed by their primary care physician in a real-life situation, adherence to medication use was considered, clinically relevant outcomes (symptoms and exacerbations) were measured, variations in drug treatment were allowed (as would be expected in real-life practice), and the trials lasted long enough (2 years) to understand effects over time. A limitation of this study was its relatively small size, which precluded a full understanding of safety issues for each treatment option. However, this type of pragmatic research is a useful model for larger studies which could be designed to compare increasing the dose of an ICS against using a lower dose of an ICS with a LABA. To ensure a large enough sample size to adequately address the risk component of asthma treatment, these studies could preferentially use administrative databases, either prospectively or retrospectively. Claims algorithms based on the modified HEDIS approach could be used to identify patients with persistent asthma. Asthma severity could also be approximated with this approach. Patient care would be determined by the primary care provider without constraints of a clinical protocol. Symptom control could be inferred from SABA dispensings. Adherence to use of long-term controllers could be measured by medication claims. Exacerbations could be defined by oral corticosteroid dispensings, acute care visits, and hospitalizations. Most important, deaths could also be tracked.

Diagnosing COPD as the basis for initiating pharmacotherapy

Similar to asthma, guidelines for COPD also depend upon categorizing severity as a basis for determining pharmaco therapy.2,8 However, unlike asthma, COPD guidelines include strict criteria for establishing the diagnosis of COPD before proceeding with severity categorization. The clinical presentations of the major COPD subtypes, chronic bronchitis and emphysema, are well recognized. COPD is eloquently defined in the Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) guideline.8 This definition, though, is not used to diagnose COPD. The GOLD guideline, and others, have an operational definition of COPD, based solely on a spirometric finding of an FEV1/forced vital capacity (FVC) ratio below 0.7 following administration of a bronchodilator, which must be met for the diagnosis of COPD to be confirmed.2,8 There are difficulties, though, with relying on a single post-bronchodilator spirometry finding to establish the diagnosis of COPD.

Performing spirometry in the office

An obvious practical problem is that primary care physicians often do not have access to spirometers in their clinic, do not train their staff on how to perform spirometry, do not perform quality control on spirometer performance, and do not understand how to interpret results.64 It is extremely unlikely that pre- and post-bronchodilator testing as part of spirometry is being routinely performed in general practice. It should also be recognized that not all patients can perform spirometry. Hardie et al asked 95 participants in a screening study of elderly asymptomatic non-smokers to perform spirometry.65 Only 71 (75%) could perform this test. The 25% who could not perform spirometry were more likely to be female and older. Before interpreting spirometry results, there are a series of technical issues that the health care provider should consider to ensure that the test was performed correctly and that the results were reproducible.66 These issues represent serious obstacles to widespread use of spirometry for diagnosing COPD.

Interpreting spirometry results

If patients can perform technically acceptable spirometry, the health care practitioner must then interpret the results. The current approach to interpreting spirometry results, though, has limitations. The absolute values for FEV1, FVC, and FEV1/FVC are not interpreted directly. Instead the actual values are compared to predicted normal values using regression equations.67 The regression equations for these predicted values are typically obtained from studying large numbers of asymptomatic, non-smoking subjects of different ages, ethnicity, and physical characteristics, such as in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III (NHANES III).68 Although predicted values have to be adjusted for ethnic differences,69,70 the highly selected populations used for developing reference values would presumably not have underlying COPD. However, other factors besides smoking probably contribute to the development of COPD, because many COPD patients never smoked.71 In a recent international study, 28% of subjects identified as having COPD by spirometry were never smokers.72 In this study, a history of asthma and, in women, lower education levels were associated with a COPD diagnosis. Interestingly, there was a suggestion in this analysis that lower educational levels in women was actually a surrogate marker of chronic exposure to biomass fuels used for cooking and heating, another recognized cause of COPD. Van Sickle et al also found that socioeconomic factors, such as high school completion, significantly affected NHANES III predicted values.73 Wagner suggested that the effect of socioeconomic status on predicted values may have been missed in the past because exclusion of smokers might have preferentially led to fewer subjects in the presumed normal group with lower socioeconomic status.74 These observations suggest that populations used to develop predicted normal regression equations might have included patients with early COPD.

Spirometry results, even when performed under rigorously controlled settings, may be variable. In two long-term trials in stable COPD patients, baseline spirometry was performed on two separate occasions between 3 and 12 weeks apart and showed substantial variability in FEV1 and FVC between the two tests.75 Spirometry results may be ambiguous when a reduced FVC, suggesting a restrictive defect, is found. Currently, little guidance is available on interpreting a reduced FEV1 in the context of a concomitant reduction in FVC.76 Spirometry results for 1831 consecutive patients showed that 470 (25.7%) had a low FVC.77 Although a low FVC should indicate a restrictive ventilatory defect, only a minority of patients with a low FVC were actually confirmed to have a reduced total lung capacity. Hyatt et al have described a nonspecific pattern of abnormal spirometry, characterized by a low FEV1 and FVC with a normal FEV1/FVC ratio, occurring in 9.5% of routine spirometries.78 In most patients with this nonspecific spirometry pattern bronchodilators did not change the results. Although this nonspecific pattern would not meet the GOLD criteria for COPD, on follow-up over 3 years, 191 (15%) of 1284 patients were confirmed to have airway obstruction.79 Consequently, a reduced FVC found on spirometry might represent COPD, but current strategies for interpreting spirometry results would not suggest this diagnosis.67

Reversibility testing

There is little information available on predicted normal FEV1, FVC, and FEV1/FVC values pre- and post-bronchodilator for the general population. The NHANES III data used for predicting normal regression equations relied on pre-bronchodilator spirometry.68 A study from Norway reported on pre- and post-bronchodilator values for normal subjects aged between 26 and 82 years, but only 515 participants were included.80 Given the small overall sample size, it is not surprising to note that there were only 39 men and 82 women included in this study over the age of 60, the relevant age for COPD. As expected, they found that the post-bronchodilator values were significantly greater than the pre-bronchodilator values. They also compared the post-bronchodilator FEV1, FVC, and FEV1/FVC values to pre-bronchodilator values predicted from standard reference equations and again found significant differences. The authors speculated that relying on only the post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC ratio might reduce the detection of obstructive airway disease. In earlier work, this same group showed that this effect did occur.81 In random screening of adults living in Hordaland County, Norway, 3% of the subjects tested had an FEV1/FVC ratio below 0.70 pre-bronchodilator but above 0.70 post-bronchodilator. The prevalence of COPD was 27% lower in this screening study using the post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC ratio rather than the pre-bronchodilator value. Interestingly, 0.5% of the screened population had a normal FEV1/FVC ratio pre-bronchodilator but a low ratio post-bronchodilator. This effect probably occurred because there may be a more robust increase in FVC post-bronchodilator than FEV1.82,83 It is often not appreciated that reversibility can be based on changes in either FEV1 or FVC.67 Failure to understand how a COPD patient might respond to a bronchodilator could result in confusing situations for the general practitioner. A patient with a low pre-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC but a normal post-bronchodilator ratio due to a vigorous FEV1 response would not be considered to have COPD. Conversely, a patient with a normal pre-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC ratio but a low post-bronchodilator ratio due to a vigorous FVC response would be diagnosed as having COPD by the GOLD guidelines.

There is uncertainty in how to perform and interpret reversibility testing.67 One approach is to administer four puffs of albuterol by metered dose inhaler with a spacer, but there is no consensus on the type of bronchodilator, the number of puffs to be administered, and the inhalation device to be used when performing reversibility testing. Administering both a SABA and a short-acting inhaled anti-muscarinic agent (SAMA) results in a greater bronchodilator effect than found with a SABA alone.82

Just as there is variability in the FEV1 over time in stable patients, there is also variability in the FEV1 response to inhaled bronchodilators in COPD over time. Calverley et al reported on bronchodilator reversibility in 660 COPD patients studied on three separate occasions at 4-week intervals and found that 52.1% of the patients changed responder status between visits.82 At some visits, patients were classified as having reversible airway obstruction, but at other visits the response to bronchodilators was not as substantial. Han et al observed a similar variability in bronchodilator responsiveness over time.83 Again, failing to understand how COPD patients respond to bronchodilators could result in odd situations which would be difficult for the general practitioner to interpret. A patient identified as having COPD because of a minimal bronchodilator effect on one visit might not have the diagnosis confirmed on another visit, because of a more robust FEV1 response to inhaled albuterol. A patient not diagnosed with COPD on one visit could have COPD diagnosed at a later visit if there were a vigorous FVC response. An important caveat to the issue of bronchodilator reversibility, often not recognized in clinical practice, is to ensure that patients do not use either their regularly scheduled long-acting bronchodilators or as-needed short-acting bronchodilators in the hours before spirometry, as use of these medications will minimize bronchodilator responsiveness in the laboratory.84

Fixed FEV1/FVC ratio

Using a fixed FEV1/FVC ratio to diagnose COPD fails to take into account the expected and normal effects of aging on FEV1 and FVC. With aging both the FEV1 and FVC decrease, but the FEV1 tends to fall to a greater extent. Consequently, the FEV1/FVC ratio normally decreases with age. This physiologic phenomenon can lead to two different types of diagnostic inaccuracies when relying on the FEV1/FVC ratio to establish the diagnosis of COPD. A younger patient with a history consistent with COPD might have an FEV1/FVC ratio above 0.70 but a ratio well below expected for their age. This patient might be incorrectly classified as not having COPD (false negative). Conversely, an older patient without a history suggesting COPD might have an FEV1/FVC ratio below 0.70 consistent with their age predicted value.85 This patient might be falsely identified as having COPD (false positive). Miller et al found that false negative findings, ie, missing the diagnosis of COPD, were more likely to occur in women younger than 45.86 Schermer et al found that false positive findings, ie, over-diagnosis of COPD, occurred more often in middle age and elderly patients.87 Robberts and Schermer showed that 16% of 3473 men referred for spirometry by their primary care physicians would have been incorrectly diagnosed with COPD if the FEV1/FVC ratio <0.70 had been the sole criteria (Figure 4).88 Although it is argued that the FEV1/FVC ratio <0.70 is a simple and practical operational definition of COPD,89 a more appropriate physiologic approach would be to use the lower limit of predicted normal for the FEV1/FVC ratio.90 Until this issue is resolved, over-diagnosis and under-diagnosis of COPD will occur.

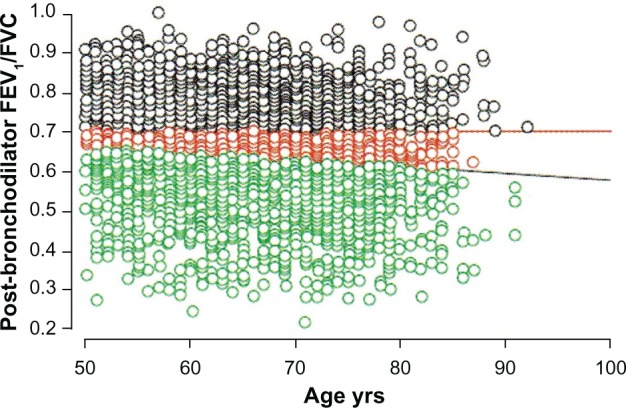

Figure 4.

The horizontal red line indicates the fixed FEV1/FVC ratio of 0.70. The black circles above this line represent patients without COPD. The predicted normal post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC ratio decreases with age. The black diagonal line represents the age-adjusted lower limit of normal for the FEV1/FVC for men. The green circles below this line represent patients with COPD. The red circles between the two lines indicate the 558 (16% of the entire cohort of 3473 men studied) symptomatic male current and ex-smokers referred for spirometry testing who would have been incorrectly diagnosed with COPD based on using the fixed threshold rather than the predicted lower limit of normal.88

Note: Reproduced from Robberts B, Schermer T. Abandoning FEV1/FVC < 0.70 to detect airway obstruction. Chest. 2011;139(5):1253–1254 with permission of the publisher.

Abbreviations: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in one second; FVC, forced vital capacity.

Pragmatic research approaches to identifying COPD patients and categorizing severity

The current operational definition of COPD, which rests solely on the post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC ratio, does not seem either workable or reasonable. There are substantial difficulties performing and interpreting the results of spirometry. These difficulties undoubtedly lead to infrequent use of spirometry by many primary care physicians, which accounts for the overall under-diagnosis and under-detection of COPD in primary care. Predicted normal reference equations are limited by the population studied and provide little information on the predicted post-bronchodilator response. Reversibility testing is not well standardized and is variable over time. Relying on a strict FEV1/FVC threshold of 0.70 ignores basic physiologic principles regarding the effect of aging on the lung. Clinical guidelines recommending treatment approaches based on a dysfunctional definition of COPD are fundamentally flawed. Curiously, recent commentaries on controversies in COPD do not mention this issue, and persist in relying on the GOLD definition of an FEV1/FVC ratio <0.70 for COPD.91,92

Pragmatic research is needed to develop a definition of COPD that is both accurate and readily usable by the primary care health practitioner. This definition should satisfy two important points. First, it should not be based on spirometry. Second, it should focus on identifying patients with more severe COPD. Recognizing the mild COPD patient, ie, a patient who is either asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic with an FEV1/FVC ratio <0.70 but an FEV1 >80% predicted, may not be helpful. Office spirometry can significantly improve early detection of COPD,93 but, as the US Preventive Services Task Force has pointed out, screening asymptomatic patients for COPD provides no net benefit.94 There is no effective treatment for preventing the accelerated decline in lung function seen in COPD other than smoking cessation. All smokers, whether they have COPD or not, should be advised to stop smoking. Excluding spirometry as a diagnostic standard and developing a definition oriented towards more severe patients should actually make the process of recognizing COPD simpler.

There are useful non-spirometry-based methods for identifying patients with COPD. A recent systematic review provided helpful insights into the diagnostic value of the history and physical examination for COPD.95 Features in the history, such as age ≥45 years, current and heavy smoking, female sex, complaints of wheeze and dyspnea, and a self-reported history of COPD, had independent diagnostic value for identifying COPD. Findings on physical examination, like wheeze and prolonged expiration, also had independent diagnostic value. Unfortunately, this systematic review included only a small number of studies and few of the studies reviewed used the FEV1/FVC ratio <0.70 as the independent determinant of COPD. Others have found that a patient reported smoking history of more than 55 pack years, wheezing heard on auscultation and patient self-reported wheezing almost assures the presence of airflow obstruction.2 Price et al developed a symptom-based questionnaire for identifying COPD in smokers which they validated by comparison to the standard COPD definition of an FEV1/FVC ratio <0.70.96 The final questionnaire contained only eight items and could be easily completed by the patient. Questions were related to age, smoking history, cough, wheeze, and allergies. The questionnaire had reasonably good performance characteristics, a specificity of 80.4%, and sensitivity of 72.0% for identifying COPD.

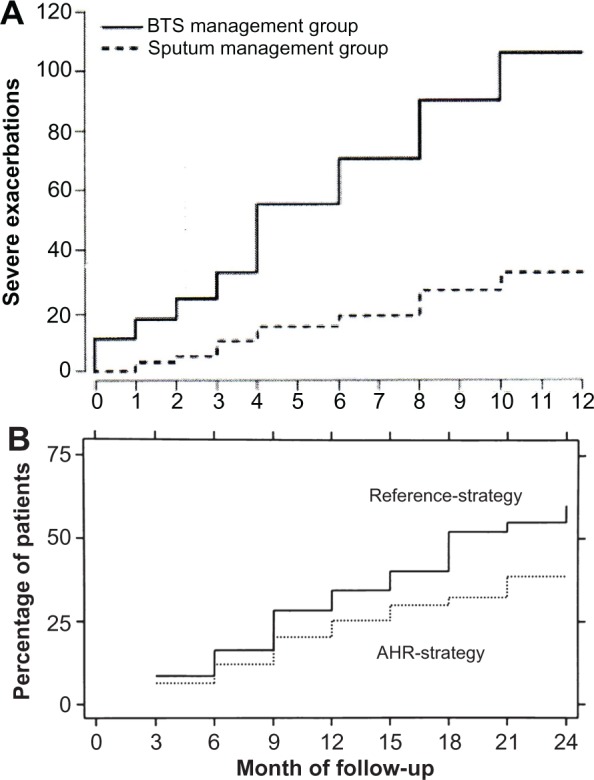

Approaches to identifying COPD patients using smoking history and symptoms could be improved by incorporating reports of exacerbations, especially those requiring hospitalization, ambulatory claims for care related to COPD, and use of bronchodilators. Recent work has shown that patients with GOLD Stage 2 COPD (an FEV1 of 50%–79% predicted) had frequent exacerbations (Figure 5).97 The first year exacerbation rate in this study for Stage 2 patients was 0.85 per person; 22% had frequent exacerbations and 7% had been hospitalized for an exacerbation. Gershon et al found that information available in an administrative database on hospitalizations and ambulatory care visits attributed to COPD by a primary care physician was a reasonably accurate way to identify COPD patients.98 In a large population study based on administrative data, these authors showed that a physician diagnosis of COPD based on either an ambulatory care claim or hospitalization was a useful approach in identifying patients with COPD over time.99 Incorporating use of medications typically used for managing COPD, such as inhaled anticholinergic and long-acting bronchodilators, can be used as part of a non-spirometry-based method for determining COPD severity.100,101

Figure 5.

As COPD severity stage increases, the frequency of exacerbations requiring hospitalization increases. The percent of patients with frequent exacerbations (ie, two or more exacerbations per year) also increased with COPD severity stage. In GOLD Stage 2 COPD the exacerbation rates were 0.85 per year. The high exacerbation rate suggests that an algorithm based on claims for COPD exacerbations could be a useful approach to identifying COPD patients in GOLD Stage 2 and above.96

Note: Reproduced from Price DB, Tinkelman DG, Halbert RJ, et al. Symptom-based questionnaire for identifying COPD in smokers. Respiration. 2006;73(3):285–295 with permission of the publisher. Copyright New England Journal of Medicine.

Abbreviations: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GOLD, Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease.

Future pragmatic research should concentrate on developing a simple, practical, and accurate method for identifying COPD patients who need treatment. Previous work suggests that a viable approach could be developed based on three components: a questionnaire regarding smoking history, exposure to other noxious dusts, and symptoms of wheeze and cough; findings on physical examination of wheeze; and an administrative database review of exacerbation history and medication use. A further refinement of this approach will be to use elements of this method, such as the number of medications being used, frequency of exacerbations, use of oxygen, etc, to then categorize COPD severity.

Pragmatic research, COPD treatment, and COPD outcomes

With a validated non-spirometric-based method for diagnosing symptomatic COPD, especially one which can also be used to categorize COPD severity, difficult questions about how treatment recommendations in the GOLD guidelines actually impact outcomes can be addressed with pragmatic research. An example of a particularly vexing question is whether currently recommended maintenance pharmacotherapy for COPD in the GOLD guidelines affects survival. For COPD patients in GOLD Stages 2, 3, and 4 severity, the guidelines recommend regular treatment with some combination of a LABA, a long-acting inhaled anti-muscarinic agent (LAMA), and a LABA with an ICS. Each of these products has proven benefits in improving lung function and reducing exacerbations. However, there are contradictory reports regarding how these products affect survival. In a 3-year industry sponsored trial, there was a nonsignificant trend for regular treatment with both a LABA and a LABA/ICS combination to reduce mortality.102 In a 4-year industry sponsored trial there was a nonsignificant trend for regular treatment with a LAMA to reduce mortality.103 A pooled safety analysis compiled from the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials performed in COPD with a LAMA during its clinical development also suggested a trend for improved survival.104 Retrospective analyses, though, suggested that use of inhaled anti-muscarinic agents, both short-acting and long-acting, was associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular deaths.105,106

The FDA has publicly commented that the safety data on LAMA use from prospective trials was more meaningful than those from the retrospective analyses.107 Unfortunately, recent data from prospective trials with a LAMA in a novel inhalation device have also suggested an increased risk of death with this drug.108,109 Complicating this situation are results from two other studies comparing outcomes between use of a LAMA and a combination LABA/ICS product and use of LAMA and a LABA. In a 2-year, double-blind, randomized, parallel, industry-sponsored study, patients treated with a LABA/ICS were significantly less likely to die than those receiving the LAMA.110 In a retrospective database analysis, moderate COPD patients initially treated with a LABA had a lower mortality rate over more than 5 years of follow-up than those begun on a LAMA.111 These findings suggest that both LABA and LABA/ICS might provide a survival benefit in COPD over LAMA. Interestingly, a systematic review compared results with LABA/ICS and LABA treatment and found that combination therapy with LABA/ICS did not reduce the risk of either death or severe exacerbations compared to LABA therapy alone.112 Although LABA/ICS therapy did provide significant improvements in lung function and quality of life compared to LABA treatment, these benefits were small and probably clinically unimportant. Use of a LABA/ICS was associated with significantly more side effects, such as pneumonia, than LABA treatment.

On balance, the results of these studies are concerning. They suggest serious possible safety concerns with both LAMA and combination LABA/ICS therapy in COPD. Surprisingly, monotherapy with a LABA might provide benefits with fewer risks than either LAMA monotherapy or combination LABA/ICS treatment. Given the widespread use of LAMA and LAB A/ICS products in COPD, there is a clear need to address this issue and pragmatic research is ideally suited for this purpose. As with asthma, large studies would be required to address these safety concerns. Prospective and/or retrospective administrative database analyses would be appropriate research models. Patients with COPD could be identified through a claims-based algorithm. Patient care decisions would be made by the local health care provider. Severity categorization could be inferred from types of therapy being used by patients. Multiple outcomes could be monitored. Exacerbations could be measured by oral corticosteroid and antibiotic dispensings along with acute care visits and hospitalizations as indicators of exacerbations. Deaths would be the ultimate outcome of concern.

Conclusion

Asthma and COPD are common diseases which cause patients and society considerable difficulties. Asthma patients suffer from limitations in their daily lives due to uncontrolled symptoms and intermittent exacerbations. Symptoms and exacerbations in COPD also disrupt daily life activities. Although asthma is associated with a low mortality rate, COPD is a deadly disease with an increasing mortality rate. Both asthma and COPD result in substantial total direct and indirect health care costs for society. Clinical practice guidelines provide comprehensive recommendations for the care of asthma and COPD patients. Health care policy makers have reasonably recognized that improving outcomes in asthma and COPD should be a priority and have emphasized consistent use of guideline recommendations to achieve this end. Unfortunately, failure to improve outcomes may not be because of inconsistent applications of guideline recommendations, but rather because these recommendations might be based on flawed assumptions. There are difficulties implementing the EPR 3 method for categorizing asthma severity and the GOLD method for diagnosing COPD. As these serve as the foundation for treatment recommendations for these diseases, simpler methods, using readily available information at both the individual practice and the large population level, should be developed to categorize asthma severity and to diagnose COPD. Once these methods are developed and validated, pragmatic research will be of great value in answering important questions about how guideline-recommended approaches, specifically regarding use of LABA/ICS in asthma and LAMA and LABA/ICS in COPD, affect outcomes in real-life situations. Ideally pragmatic research methods developed for use in North America and Europe could be applied worldwide.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The author has served as a speaker/advisory board member/consultant to Teva, MedImmune, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Merck, Schering-Plough, GlaxoSmithKline, Genentech, Pfizer, and Eli Lilly.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics Asthma. [Accessed October 5, 2011]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/Asthma/

- 2.Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Weinberger SE, et al. Diagnosis and management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(3):179–191. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-3-201108020-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Heart Lung and Blood Institute COPD for Health Care Professionals. [Accessed October 5, 2011]. Available from: http://www.nhlbi.gov/health/public/lung/copd/index.htm.

- 4.Sullivan PW, Ghushchyan VH, Slejko JF, Belozeroff V, Globe DR, Lin SL. The burden of adult asthma in the United States: evidence from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127(2):363–369. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Deaths from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease – United States, 2000–2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57(45):1229–1232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Asthma Education and Prevention Program . Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute; 2007. [Accessed October 5, 2011]. Available from: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/asthma. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Global Initiative for Asthma Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention. [Accessed October 5, 2011]. Updated 2010. Available from: http://www.ginaasthma.org/guidelines-global-strategy-for-diagnosis-management.html.

- 8.Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. [Accessed October 5, 2011]. Updated 2010. Available from: http://www.goldcopd.org.

- 9.Asthma in America: a landmark survey. [Accessed October 5, 2011]. Available from: http://www.asthmainamerica.com/aaa_index.html.

- 10.Blaiss MS, Meltzer E, Murphy KR, Nathan R, Stoloff SW. Executive summary: asthma insight and management. [Accessed October 5, 2011]. Available from: http://www.takingaimatasthma.com/pdf/executive-summary.pdf.

- 11.Heffner JE, Mularski RA, Calverley PM. COPD performance measures: missing opportunities for improving care. Chest. 2010;137(5):1181–1189. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-2306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campbell SM, Reeves D, Kontopantelis E, Sibbald B, Roland M. Effects of pay for performance on the quality of primary care in England. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(4):368–378. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0807651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Herck P, De Smedt D, Annemans L, Remmen R, Rosenthal MB, Sermeus W. Systematic review: Effects, design choices, and context of pay-for-performance in health care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:247. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herland K, Akselsen JP, Skjønsberg OH, Bjermer L. How representative are clinical study patients with asthma or COPD for a larger “real life” population of patients with obstructive lung disease? Respir Med. 2005;99(1):11–19. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2004.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Travers J, Marsh S, Williams M, et al. External validity of randomized controlled trials in asthma: to whom do the results of the trials apply? Thorax. 2007;62(3):219–223. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.066837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Asthma Education and Prevention Program Expert Panel Report 2: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute 1997. [Accessed October 5, 2011]. Available from: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/asthma.

- 17.Legorreta AP, Christian-Herman J, O’Connor RD, Hasan MM, Evans R, Leung KM. Compliance with national asthma management guidelines and specialty care. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(5):457–464. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.5.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rastogi D, Shetty A, Neugebauer R, Harijith A. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute guidelines and asthma management practices among inner-city pediatric primary care providers. Chest. 2006;129(3):619–623. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.3.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fuhlbrigge AL, Adams RJ, Guilbert TW, et al. The burden of asthma in the United States: level and distribution are dependent on interpretation of the national asthma education and prevention program guidelines. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166(8):1044–1049. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2107057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bacharier LB, Strunk RC, Mauger D, White D, Lemanske RF, Jr, Sorkness CA. Classifying asthma severity in children: mismatch between symptoms, medication use, and lung function. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170(4):426–432. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200308-1178OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Doerschug KC, Peterson MW, Dayton CS, Kline JN. Asthma guidelines: an assessment of physician understanding and practice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159(6):1735–1741. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.6.9809051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baker KM, Brand DA, Hen J., Jr Classifying asthma: disagreement among specialists. Chest. 2003;124(6):2156–2163. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.6.2156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diette GB, Krishnan JA, Wolfenden LL, Skinner EA, Steinwachs DM, Wu AW. Relationship of physician estimate of underlying asthma severity to asthma outcomes. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2004;93(6):546–552. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61261-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wolfenden LL, Diette GB, Krishnan JA, Skinner EA, Steinwachs DM, Wu AW. Lower physician estimate of underlying asthma severity leads to undertreatment. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(2):231–236. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.2.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vignola AM, Chanez P, Campbell AM, et al. Airway inflammation in mild intermittent and in persistent asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157(2):403–409. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.2.96-08040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van den Toorn LM, Overbeek SE, de Jongste JC, Leman K, Hoogsteden HC, Prins JB. Airway inflammation is present during clinical remission of atopic asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(11):2107–2103. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.11.2006165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Farah CS, Kermode JA, Downie SR, et al. Obesity is a determinant of asthma control independent of inflammation and lung mechanics. Chest. 2011;140(3):659–666. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Colice GL, Burgt JV, Song J, Stampone P, Thompson PJ. Categorizing asthma severity. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160(6):1962–1967. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.6.9902112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greening AP, Ind PW, Northfield M, Shaw G. Added salmeterol versus higher-dose corticosteroid in asthma patients with symptoms on existing inhaled corticosteroid. Allen and Hanburys Limited UK Study Group. Lancet. 1994;344(8917):219–224. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)92996-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thomas M, von Ziegenweidt J, Lee AJ, Price D. High-dose inhaled corticosteroids versus add-on long-acting β-agonists in asthma: an observational study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123(1):116–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O’Byrne PM, Reddel HK, Colice GL. Does the current stepwise approach to asthma pharmacotherapy encourage over-treatment? Respirology. 2010;15(4):596–602. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2010.01728.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bateman ED, Boushey HA, Bousquet J, et al. Can guideline-defined asthma control be achieved? The Gaining Optimal Asthma Control study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170(8):836–844. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200401-033OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Green RH, Brightling CE, McKenna S, et al. Asthma exacerbations and sputum eosinophil counts. Lancet. 2002;360(9347):1715–1721. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11679-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sont JK, Willems LN, Bel EH, van Kreiken JH, Vandenbroucke JP, Sterk PJ. Clinical control and histopathologic outcome of asthma when using airway hyperresponsiveness as an additional guide to long-term treatment. The AMPUL Study Group. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159(4 Pt 1):1043–1051. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.4.9806052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Szefler SJ, Mitchell H, Sorkness CA, et al. Management of asthma based on exhaled nitric oxide in addition to guideline-based treatment for inner-city adolescents and young adults: a randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9643):1065–1072. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61448-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shaw DE, Berry MA, Thomas M, et al. The use of exhaled nitric oxide to guide asthma management: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176(3):231–237. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200610-1427OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith AD, Cowan JO, Brassett KP, Herbison GP, Taylor DR. Use of exhaled nitric oxide measurements to guide treatment in chronic asthma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(21):2163–2173. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berger WE, Legorreta AP, Blaiss MS, et al. The utility of the Health Plan Employer Data and Information Set (HEDIS) asthma measure to predict asthma-related outcomes. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2004;93(6):538–545. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61260-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cabana MD, Slish KK, Nan B, Clark NM. Limits of the HEDIS criteria in determining asthma severity for children. Pediatrics. 2004;114(4):1049–1055. doi: 10.1542/peds.2003-1162-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gelfand EW, Colice GL, Fromer L, Bunn WB, III, Davies TJ. Use of the health plan employer data and information set for measuring and improving the quality of asthma care. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006;97(3):298–305. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60793-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Colice GL, Yu AP, Ivanova JI, et al. Costs and resource use of mild persistent asthma patients initiated on controller therapy. J Asthma. 2008;45(4):293–299. doi: 10.1080/02770900801911178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Colice G, Wu EQ, Birnbaum H, Daher M, Marynchenko MB, Varghese S. Healthcare and workloss costs associated with patients with persistent asthma in a privately insured population. J Occup Environ Med. 2006;48(8):794–802. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000229819.26852.0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Birnbaum HG, Ivanova JI, Yu AP, et al. Asthma severity categorization using a claims-based algorithm or pulmonary function testing. J Asthma. 2009;46(1):67–72. doi: 10.1080/02770900802503099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fuhlbrigge AL, Carey VJ, Finkelstein JA, et al. Validity of the HEDIS criteria to identify children with persistent asthma and sustained high utilization. Am J Manag Care. 2005;11(5):325–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schatz M, Zeiger RS. Improving asthma outcomes in large populations. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128(2):273–277. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Paris J, Peterson EL, Wells K, et al. Relationship between recent short-acting beta-agonist use and subsequent asthma exacerbations. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008;101(5):482–487. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60286-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schatz M, Zeiger RS, Vollmer WM, et al. Validation of a beta-agonist long-term asthma control scale derived from computerized pharmacy data. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117(115):995–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.01.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.FDA News Release . Over-the-counter asthma inhalers containing chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) will no longer be sold after December 31, 2011. Targeted News Service; Sep 22, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schatz M, Zweiger RS, Vollmer WM, et al. The controller-to-total asthma medication ratio is associated with patient-centered as well as utilization outcomes. Chest. 2006;130(1):43–50. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schatz M, Nakahiro R, Crawford W, Mendoza G, Mosen D, Stibolt TB. Asthma quality-of-care markers using administrative data. Chest. 2005;128(4):1968–1973. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.4.1968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yong PL, Werner RM. Process quality measures and asthma exacerbations in the medicaid population. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124(5):961–966. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Firoozi F, Lemière C, Beauchesne MF, Forget A, Blais L. Development and validation of database indexes of asthma severity and control. Thorax. 2007;62(7):581–587. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.061572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gershon AS, Wang C, Guan J, Vasilevska-Ristovska J, Cicutto L, To T. Identifying patients with physician-diagnosed asthma in health administrative databases. Can Respir J. 2009;16(6):183–188. doi: 10.1155/2009/963098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Busse WW. Asthma diagnosis and treatment: filling in the information gaps. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128(4):740–750. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ni Chroinin M, Greenstone I, Lasserson TJ, Ducharme FM. Addition of long-acting beta2-agonists to inhaled steroids as first line therapy for persistent asthma in steroid-naïve adults and children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;4:CD005307. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005307.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Blanchette C, Culler SD, Ershoff D, Gutierrez B. Association between previous health care use and initiation of inhaled corticosteroid and long-acting beta2-adrenergic agonist combination therapy among US patients with asthma. Clin Ther. 2009;31(11):2574–2583. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ye X, Gutierrez B, Zarotsky V, Nelson M, Blanchette CM. Appropriate use of inhaled corticosteroid and long-acting beta2-adrenergic agonist combination therapy among asthma patients in a US commercially insured population. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25(9):2251–2258. doi: 10.1185/03007990903155915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Friedman H, Wilcox T, Reardon G, Crespi S, Yawn BP. A retrospective study of the use of fluticasone propionate/salmeterol combination therapy as initial asthma controller in a commercially insured population. Clin Ther. 2008;30(10):1908–1917. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chowdhury BA, Dal Pan G. The FDA and safe use of long-acting beta-agonists in the treatment of asthma. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(13):1169–1171. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1002074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bateman E, Nelson H, Bousquet J, et al. Meta-analysis: effects of adding salmeterol to inhaled corticosteroids on serious asthma-related events. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(1):33–42. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-1-200807010-00229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sears MR, Ottosson A, Radner F, Suissa S. Long-acting beta-agonists: a review of formoterol safety data from asthma clinical trials. Eur Respir J. 2009;33(1):21–32. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00145006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wijesinghe M, Weatherall M, Perrin K, Harwood M, Beasley R. Risk of mortality associated with formoterol: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J. 2009;34(4):803–811. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00159708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Price D, Musgrave SD, Shepstone L, et al. Leukotriene antagonists as first-line or add-on asthma-controller therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(18):1695–1707. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1010846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kaminsky DA, Marcy TW, Bachand M, Irvin CG. Knowledge and use of office spirometry for the detection of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease by primary care physicians. Respir Care. 2005;50(12):1639–1648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hardie JA, Buist AS, Vollmer WM, Ellingsen I, Bakke PS, Mørkve O. Risk of over-diagnosis of COPD in asymptomatic elderly never-smokers. Eur Respir J. 2002;20(5):1117–1122. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00023202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J. 2005;26(2):319–338. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pellegrino R, Viegi G, Brusasco V, et al. Interpretative strategies for lung function tests. Eur Respir J. 2005;26(5):948–968. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00035205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hankinson JL, Odencrantz JR, Fedan KB. Spirometric reference values from a sample of the general US population. Am J Respir Crit Care. 1999;159(1):179–187. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.1.9712108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Stanojevic S, Wade A, Stocks J, et al. Reference ranges for spirometry across all ages: a new approach. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177(3):253–260. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200708-1248OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hankinson JL, Kawut SM, Shahar E, Smith LJ, Sutkovsky KH, Barr RG. Performance of American Thoracic Society-recommended spirometry reference values in a multiethnic sample of adults: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA) lung study. Chest. 2010;137(1):138–145. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-0919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Salvi SS, Barnes PJ. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in nonsmokers. Lancet. 2009;374(9691):733–743. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61303-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lamprecht B, McBurnie MA, Vollmer WM, et al. COPD in never smokers: results from the population-based burden of obstructive lung disease study. Chest. 2011;139(4):752–763. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Van Sickle D, Magzamen S, Mullahy J. Understanding socioeconomic and racial differences in adult lung function. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184(5):521–527. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201012-2095OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wagner PD. FEV1 in the suburbs: choose your research subjects wisely. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184(5):495–496. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201105-0896ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Herpel LB, Kanner RE, Lee SM, et al. Variability of spirometry in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: results from two clinical trials. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173(10):1106–1113. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200506-975OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gardner ZS, Ruppel GL, Kaminsky DA. Grading the severity of obstruction in mixed obstructive-restrictive lung disease. Chest. 2011;140(3):598–603. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-2860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Aaron SD, Dales RE, Cardinal P. How accurate is spirometry at predicting restrictive pulmonary impairment? Chest. 1999;115(3):869–873. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.3.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hyatt RE, Cowl CT, Bjoraker JA, Scanlon PD. Conditions associated with an abnormal nonspecific pattern of pulmonary function tests. Chest. 2009;135(2):419–424. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Iyer VN, Schroeder DR, Parker KO, Hyatt RE, Scanlon PD. The nonspecific pulmonary function test: longitudinal follow-up and outcomes. Chest. 2011;139(4):878–886. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Johannessen A, Lehmann S, Omenaas ER, et al. Post-bronchodilator spirometry reference values in adults and implications for disease management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173(12):1316–1325. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200601-023OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Johannessen A, Omenaas ER, Bakke PS, Gulsvik A. Implications of reversibility testing on prevalence and risk factors for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a community study. Thorax. 2005;60(10):842–847. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.043943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Calverley PM, Burge PS, Spencer S, Anderson JA, Jones PW. Bronchodilator reversibility testing in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2003;58(8):659–664. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.8.659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Han MK, Wise R, Mumford J, et al. Prevalence and clinical correlates of bronchoreversibility in severe emphysema. Eur Resp J. 2010;35(5):1048–1056. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00052509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hanania NA, Celli BR, Donohue JF, Martin UJ. Bronchodilator reversibility in COPD. Chest. 2011;140(4):1055–1063. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-2974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Culver BH. Obstructive? Restrictive? Or a ventilatory impairment? Chest. 2011;140(3):568–569. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-0935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Miller MR, Quanjer PH, Swanney MP, Ruppel G, Enright PL. Interpreting lung function data using 80% predicted and fixed thresholds misclassifies more than 20% of patients. Chest. 2011;139(1):52–59. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Schermer TR, Smeele IJ, Thoonen BP, et al. Current clinical guideline definitions of airflow obstruction and COPD overdiagnosis in primary care. Eur Respir J. 2008;32(4):945–952. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00170307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Robberts B, Schermer T. Abandoning FEV1/FVC <0.70 to detect airway obstruction. Chest. 2011;139(5):1253–1254. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-3099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Celli BR, Halbert RJ. Point: should we abandon FEV1/FVC <0.70 to detect airway obstruction? No. Chest. 2010;138(5):1037–1040. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Enright P, Brusasco V. Counterpoint: should we abandon FEV1/FVC < 0.70 to detect airway obstruction? Yes. Chest. 2010;138(5):1040–1042. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-2052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Rabe KF, Wedzicha JA. Controversies in treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet. 2011;378(9795):1038–1047. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61295-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Agustí A, Vestbo J. Current controversies and future perspectives in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184(5):507–513. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201103-0405PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Buffels J, Degryse J, Heyrman J, Decramer M, DIDASCO Study Office spirometry significantly improves early detection of COPD in general practice: the DIDASCO study. Chest. 2004;125(4):1394–1399. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.4.1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.US Preventive Services Task Force Screening for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease using spirometry: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(7):529–534. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-7-200804010-00212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Broekhuizen BD, Sachs AP, Oostvogels R, Hoes AW, Verheij JM, Moons KG. The diagnostic value of history and physical examination for COPD in suspected or known cases: a systematic review. Family Pract. 2009;26(4):260–268. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmp026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Price DB, Tinkelman DG, Halbert RJ, et al. Symptom-based questionnaire for identifying COPD in smokers. Respiration. 2006;73(3):285–295. doi: 10.1159/000090142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hurst JR, Vestbo J, Anzueto A, et al. Susceptibility to exacerbation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(12):1128–1138. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]