Abstract

“What is the O2 concentration in a normoxic cell culture incubator?” This and other frequently asked questions in hypoxia research will be answered in this review. Our intention is to give a simple introduction to the physics of gases that would be helpful for newcomers to the field of hypoxia research. We will provide background knowledge about questions often asked, but without straightforward answers. What is O2 concentration, and what is O2 partial pressure? What is normoxia, and what is hypoxia? How much O2 is experienced by a cell residing in a culture dish in vitro vs in a tissue in vivo? By the way, the O2 concentration in a normoxic incubator is 18.6%, rather than 20.9% or 20%, as commonly stated in research publications. And this is strictly only valid for incubators at sea level.

Keywords: gas laws, hypoxia-inducible factor, Krogh tissue cylinder, oxygen diffusion, partial pressure, tissue oxygen levels

Introduction

A criticism often heard in hypoxia research is that the setting “1% O2” in a cell culture incubator does not match any physiological situation in vivo. So, what is a physiological O2 concentration in the body? What is normoxia, and what is hypoxia? With the exponential rise in our knowledge on hypoxia-inducible signaling pathways, it has become increasingly clear to every scientist cultivating cells in vitro that not only temperature, humidity, and CO2 but also O2 needs to be controlled. Corresponding incubators are on the way to becoming standard equipment for cell culture, just like it has been standard for decades to control CO2. It appears obvious that the precise O2 concentration cells are exposed to in these incubators must be disclosed in scientific publications. But, quite remarkably, in contrast to the measured hypoxic O2 concentrations, the actual normoxic O2 concentrations are almost never correctly indicated but rather given as “21%”, “20.9%”, or “20%” O2, which corresponds to the O2 concentration of dry room air rather than incubator air. This review is addressed to newcomers to the hypoxia research field and explains the simple but not always intuitive properties of gases required for the daily work in cell culture. Herein, we will also discuss the actual O2 concentration, or better O2 partial pressure, inside tissues and cultured cells, a point that has all too often been subjected to over-simplifications. Using the example of the normoxic O2 concentration in a cell culture incubator, a simple introduction to the physics of gases will be given.

What is the O2 concentration in the gas phase?

Whether at sea level or Mount Everest, whether on a pole or the equator, the O2 concentration is always the same! The value of sufficient precision for biological considerations is 20.9% (volume/volume or v/v). However, this value is for dry air only, ignoring the fact that there is usually also water in its gaseous form in the atmosphere. The other gases in the air, mostly nitrogen, are not really relevant for cellular processes under physiological conditions.

What is the O2 partial pressure?

What changes at high altitude is not the concentration of any given gas but the total pressure of the air. Air pressure at a given altitude is built up by the height of the air column above. This air column has a certain mass that exerts force onto the gas below it under the influence of gravity. Because in contrast to liquids gases are compressible, the density of the air increases exponentially rather than linearly with the height/weight of the overlaying air column. Vice versa, air pressure falls exponentially with increasing altitude. The corresponding physical law allows the calculation of the decrease in atmospheric pressure with increasing altitude (a) expressed in kilometers (km), assuming that earth’s gravity is equal on the entire surface of the planet (which is a simplification, of course): Pa = P0 × e−(0.127×a). P0 is the atmospheric pressure at sea level. For this calculation, it does not matter which pressure unit is chosen. The official unit is Newton (the unit of force) per square meter (N/m2), also called Pascal (Pa). At sea level, the atmospheric pressure is 101.3 kPa. However, biologists still prefer the old unit millimeter mercury (mmHg), also called Torr (torr). At sea level, a manometer filled with mercury shows a column height of 760 mm (ie, 101.3 kPa = 760 mmHg). This is an average value that is only theoretically constant, since both minor changes in gravity as well as, more importantly, the actual weather condition can slightly affect this value. The 20.9% of this total atmospheric pressure will result in the O2 partial pressure (pO2), that is, 159 mmHg. According to the formula mentioned earlier, at 0.5 km altitude, for instance, the atmospheric pressure is 713.2 mmHg, and the pO2 is 149.1 mmHg.

Why must humidity be considered?

Cultured cells must be kept in 100% (relative to saturation) humidified incubators. Otherwise, the medium evaporates, and cell metabolism is compromised by changes in osmolarity, eventually resulting in cell death. Evaporated water molecules in the gas phase also generate a partial gas pressure, pH2O. This pressure is even built up if the gas is in equilibrium with its frozen aggregation state (ie, ice) by a process called sublimation. The pH2O increases with increasing temperature of the liquid source of the evaporated water, assuming that liquid and gas phases have the same temperature. Because tissue culture incubators usually mimic the human core body temperature, their temperature is set to 37°C, resulting in a pH2O of 47 mmHg. Remarkably, this partial pressure is independent of the atmospheric pressure. As long as there is a balance between the liquid and gas phases, that is, the gas phase is water saturated, there is always a pH2O of 47 mmHg at 37°C, whether we are at sea level, on Mount Everest, or in a vacuum chamber. That is also one of the reasons why cosmonauts cannot leave their spaceships without pressure suits: their body fluids of 37°C temperature would start to boil if exposed to environmental atmospheric pressure <47 mmHg (eg, the water of the lung alveolar surface), which according to the formula mentioned earlier happens at >22 km altitude.

What is the O2 concentration in a normoxic incubator?

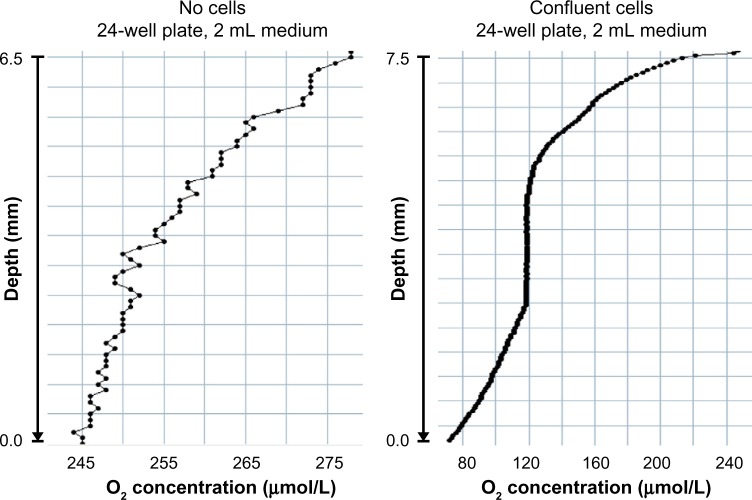

In order to understand how all relevant gases in a cell culture incubator, that is, N2, O2, H2O, and CO2, sum up to the total atmospheric pressure, which is the same inside and outside normobaric incubators, we need a simple physical law, also called Dalton’s law. It says that gas partial pressures are additive. This means that the partial pressures of all relevant gases together must be equal to the atmospheric pressure. The pH2O is 47 mmHg if we culture the cells at 37°C. The CO2 concentration is usually set (and measured) at 5% (v/v), resulting in a pCO2 of 5% of 760 mmHg, that is, 38 mmHg. Therefore, the remaining dry room air in the incubator has only 760-47-38 = 675 mmHg at its disposal. The 20.9% thereof is required for O2, resulting in a pO2 of 141 mmHg. This partial pressure corresponds to an O2 concentration of 18.6%, the “true” normoxic oxygen condition in every day’s cell culture (Figure 1). However, this is correct only at sea level. At 0.5 km altitude, for example, the pO2 would be 20.9% of 713.2-47-35.7 = 630.5 mmHg, that is, 131.8 mmHg, corresponding to an O2 concentration of 131.8/713.2×100% = 18.5%. Thus, the relative effect of the constant pH2O on the final O2 concentration increases with increasing altitude.

Figure 1.

Composition of the gas phase in a tissue culture incubator.

Notes: Input room air (left) is mixed with gaseous water and CO2 to form the incubator’s gas mixture (right).

What is the O2 concentration in the liquid phase?

As nice as it is to know the O2 concentration in the gas phase, it will never be what the (adherent) cells in a tissue culture dish actually experience, since they are attached to the bottom of the dish. To understand how oxygen actually reaches the cells, another simple physical law is required, also called Henry’s law. It says that the partial pressure of a gas in the liquid phase is equal to its partial pressure in the gas phase. Whereas this law is neither dependent on the nature of the gas nor of the liquid, the actual gas solubility is highly variable between different gases and liquids. At least, the dissolved gas concentration can easily be calculated as it is directly proportional to the partial pressure. The solubility constant, also called Bunsen’s constant, is a specific number for each gas, depending on the nature and composition of the liquid as well as on the temperature. At 37°C, 1.32 μM O2 dissolves in pure water per 1 mmHg O2 partial pressure. However, the presence of dissolved salts lowers O2 solubility. If we take as a likely approximation that typical cell culture media have properties similar to blood plasma, the plasma O2 solubility of 1.26 μM O2 per 1 mmHg at 37°C1 would result in 1.26 μM/mmHg ×141 mmHg = 177.66 μM O2 concentration under normoxic incubator conditions. This value increases in a nonlinear manner with decreasing temperature and vice versa. Importantly, O2 solubility in the aqueous phase is rather low, and other biologically relevant gases have clearly distinct solubility constants. CO2, for instance, dissolves in blood plasma at 30 μM per 1 mmHg CO2 partial pressure,1 that is, in a 5% CO2 incubator, this would result in 30 μM/mmHg ×38 mmHg = 1,140 μM CO2 concentration.

How is O2 distributed in the liquid phase?

Strictly speaking, Henry’s law is only valid for stirred liquids or for the liquid phase just below the surface in resting liquids. At least for adherent cell culture, the medium is usually not stirred. Unfortunately, under these typical cell culture conditions, O2 will not reach the cells at the same partial pressures (or concentrations) as calculated earlier. The mechanism by which gases reach the bottom of the tissue culture dish or flask is by diffusion, which is almost always “the” limiting factor for cellular oxygenation. This is also called diffusion limitation. As described by Fick’s law, diffusion is directly proportional to the partial pressure difference (ie, the driving force of diffusion), directly proportional to solubility, and inversely proportional to the diffusion distance. As a rule of thumb, O2 diffusion in tissues becomes limited at ∼100–200 μm.2–4 This is not a problem for our lungs, where the diffusion distance from the alveolar surface to the hemoglobin inside the erythrocytes is only ∼2 μm.1 However, in a “10 cm” petri dish, ∼10 mL medium is required, resulting in a medium height of 1.72 mm (assuming an inner diameter of 8.6 cm and a culture area of 58 cm2). This exceeds the O2 diffusion limit by an order of magnitude and will inevitably result in an (unknown) low pericellular pO2 and poor cellular oxygenation, eventually resulting in hypoxic cells even under normoxic incubator conditions. In contrast, because the solubility of CO2 is ∼24-fold higher than that of O2 (as explained in the section “What is the O2 concentration in the liquid phase?”), CO2 diffusion is usually not limited in cell culture. As the usual bicarbonate buffer system used in cell culture determines the actual pH in equilibrium with the CO2 concentration, equal CO2 distribution also ensures equal pH values.

Taken together, O2 diffusion is dependent on the driving force (the delta pO2 or ΔpO2) and several matter constants that cannot be altered in cell culture such as the poor O2 solubility. The ΔpO2 is the difference between the incubator’s pO2 and the pericellular pO2, that is, the difference between O2 supply and O2 sink. In principle, the ΔpO2 can be decreased by lowering the pO2 in the incubator (eg, by experimental hypoxic conditions) and/or by elevating the pericellular pO2 (eg, by lowered cell density and/or lowered O2 consumption). To make the situation even more complex, an important physiological mechanism of cellular adaptation to hypoxia is lowered mitochondrial O2 consumption. Thus, the pericellular pO2 is also a function of time since these adaptive processes can take hours to days.

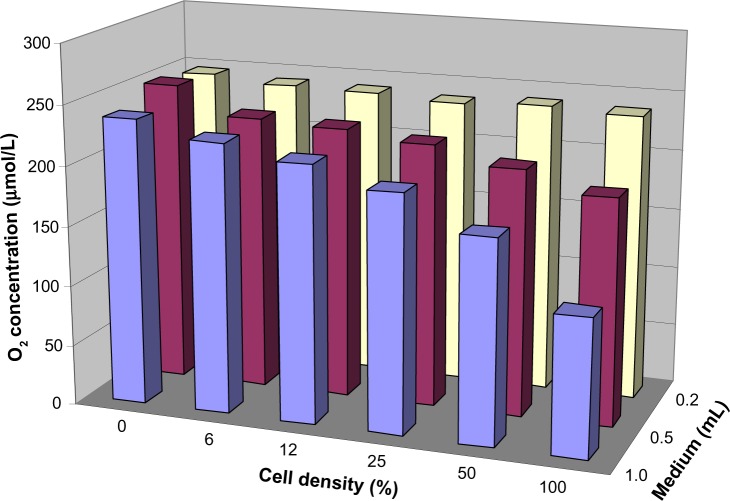

Figure 2 shows exemplary results of pO2 measurements as a function of the distance from the surface of the medium toward the bottom of a cell culture dish. After moving the dish out of an normoxic incubator and exposing it to room air conditions, the environmental O2 supply acutely increases and a shallow pO2 gradient forms due to the poor O2 diffusion in unstirred medium, even in the absence of cells (left panel). When cells are present at high density attached to the bottom of the dish (right panel), they consume considerable amounts of O2 and form an O2 sink. The resulting steep pO2 gradient leads, on the one hand, to a strong ΔpO2 as driving force for the O2 flux from the gas phase toward the cells. On the other hand, this O2 sink creates its own pericellular hypoxic microenvironment, even if the incubator’s gas phase was set to “normoxic” conditions.5 Note that the O2 concentration profile is non-steady. This is the result of increased O2 solubility due to decreased culture medium temperature profiles combined with uncontrolled convection at different medium heights when the culture dish is taken out of the incubator. Altogether, these hardly controllable variables result in nonpredictable O2 concentration profiles.

Figure 2.

O2 concentration gradients in cell culture medium.

Notes: Normal 24-well tissue culture plates without (left) or with (right) confluent HeLa cell layers were removed from a normoxic 37°C incubator, and O2 concentration profiles were determined under room air conditions at 25°C using a needle-type O2 sensor (PreSens, Regensburg, Germany). Note that the change from incubator air to room air results in a higher pO2 (no gaseous water, no pCO2) and a better O2 solubility (temperature change from 37°C to 25°C).

What is the influence of the geometry of tissue culture flasks and dishes?

One should be aware that the culture medium pO2 gradient also leads to differing pO2 levels at the bottom of uneven medium heights, such as in the tilted neck region of tissue culture flasks or below the meniscus region of tissue culture dishes. The relative proportion of these areas becomes higher when the flasks and dishes are smaller. Especially in 96-well dishes, a large proportion of cells are located along the outer rim, that is, below higher fluid levels, due to the adhesive forces that “lift” the water along the plastic walls of the dish. Thus, the actual average pO2 level can be different depending on the geometry of the used plasticware, even in the same hypoxia chamber. This might also explain variabilities between research groups, underlying the need for clear statements about this issue in the “Methods” section of a publication. Obviously, it is important to keep all tissue culture dishes absolutely horizontal, especially regarding the minimal medium volume that must be used in hypoxic experiments. A water level may be required to adjust the horizontal orientation of the dishes and to prevent uneven medium heights.

What is the pericellular pO2 in cultured cells?

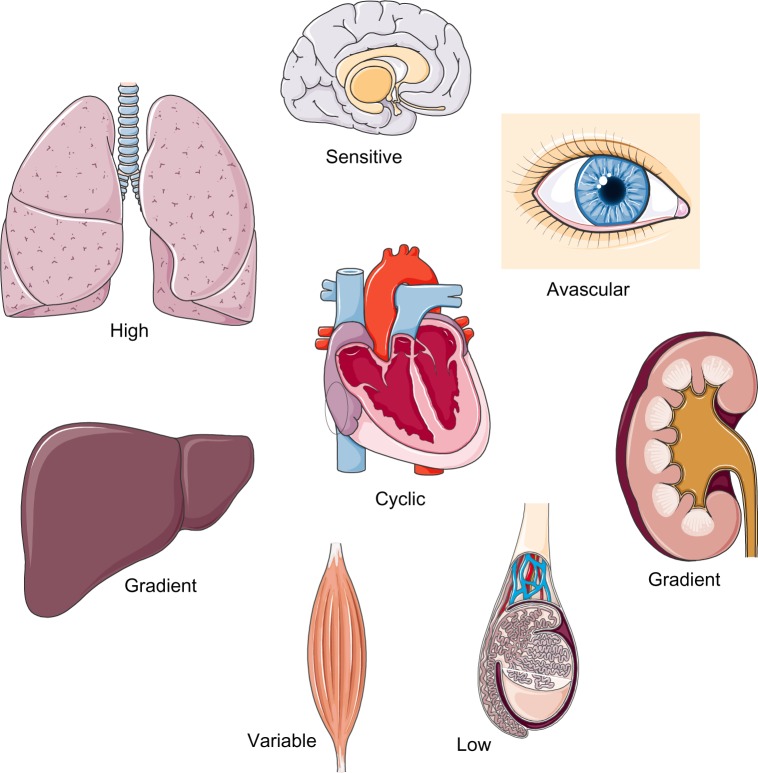

As discussed earlier, only pericellular “on-line” pO2 measurements would allow for accurate monitoring of the actual O2 availability of cultured cells. Figure 3 shows an exemplary result of pericellular pO2 measurements as function of medium height and cell density. As expected, based on theoretical considerations,6 the pericellular pO2 drops with increasing medium height and cell density. Somewhat frustratingly, these results clearly demonstrate that the knowledge of the precise O2 concentration in the incubator air is quite useless for the prediction of the pericellular pO2. So, how can this problem be solved? The usual approach is to ignore it and to simply compare “normoxic” with “hypoxic” exposure under otherwise identical conditions, knowing that these expressions refer to the incubator’s air composition only and have nothing to do with the physiological tissue situation. More precisely, but rarely done, the pericellular pO2 could be measured just below the cells, using oxygen-sensitive phosphorescent dyes (as used in Figure 3). Another approach would be the use of O2 permeable cell culture dishes, where O2 reaches the cells by diffusion through the bottom plastics and where the pO2 can hence be assumed to be identical to the gas phase.7 Unfortunately, many cell lines poorly adhere to such dishes, which are hence rarely used.

Figure 3.

Pericellular O2 concentration as a function of medium height and cell density.

Notes: 24-Well SensorDish tissue culture plates were filled with different medium volumes and seeded with HeLa cells at various densities, resulting in 0%–100% confluency as indicated. The SensorDishes were removed from the 37°C incubator and the pericellular O2 concentration determined under room air conditions at 25°C (resulting in a higher pO2 and better O2 solubility than within the incubator) using a SensorDish Reader (PreSens, Regensburg, Germany).

How long does it take to reach hypoxic conditions?

The onset of hypoxic exposure is usually defined as the moment when the doors of the hypoxic incubator are closed. However, it will take several minutes to several hours until the medium O2 concentration asymptotically approximates the desired value, even if the incubator would change the gas phase composition rapidly.8,9 A theoretical calculation with 1.72 mm medium height (refer to section “How is O2 distributed in the liquid phase?) in the absence of cells reveals a duration of 38 minutes, 45 minutes, and 60 minutes to fall below a pO2 value of 1.2-fold of the input value if a cell culture dish is acutely switched from 20% O2 to 2%, 1%, or 0.2% O2 concentration, respectively.

One possibility to circumvent this problem is to pre-equilibrate the medium in the hypoxic incubator by removing the cap of the medium bottle. However, without stirring, this will result in little change in the overall O2 content since only the surface region actually releases O2. A better solution to this problem would be to bubble nitrogen through the medium, to shake it vigorously, or to use large petri dishes with small medium heights for pre-equilibration. Somehow counterintuitively, bulk medium pre-equilibration works more efficiently if the medium is cooled while removing O2 and then warmed up again under the desired hypoxic conditions before use. A more or less immediate O2 equilibration of the cells can be expected if O2 permeable cell culture dishes are used. Finally, for suspension cells, so-called tonometers have been applied, allowing a tight control of the culture medium oxygenation by using spinning cups that generate very thin liquid layers along the cups’ walls while simultaneously exposing these liquid layers to high gas flow rates.10,11

How long does it take to lose hypoxic conditions?

Unfortunately, even the briefest opening of an incubator’s door will ruin a hypoxic experiment. Gas exchange with room air occurs almost instantaneously, and it will take up to 1 hour until hypoxic conditions in the incubator’s gas phase are reestablished (the theoretical considerations outlined earlier are valid in both directions). There is little tolerance toward reoxygenation because this immediately generates reactive oxygen species, which are well known to have signaling, as well as toxic, properties. To prevent such reoxygenation artifacts, the incubator is allowed to be opened only at the time of cell collection, and all harvesting must be performed as quickly as possible, replacing the medium immediately with precooled washing or lysis solutions. It is always better to culture, harvest, and lyse the cells within hypoxic workstations. However, one should be aware that certain biological reactions, such as O2 sensing by hypoxia-inducible factor α (HIFα) prolyl-4-hydroxylation, will continue even in (non-denatured) cell lysates whenever O2 is available.12,13

What is the O2 concentration in biological fluids?

For biological purposes, it is often more important to know the pO2 than the O2 concentration, that is, the total O2 present in a certain volume of the fluid phase. In fact, the O2 concentration is the sum of dissolved O2 plus O2 bound to proteins. The dissolved O2 is proportional to the pO2 (as discussed earlier). Bound O2 depends, in addition to pO2, on the O2 affinity, concentration, and composition of O2-binding proteins. For example, in arterial blood, only a small part of O2 is dissolved and >98% of O2 is bound to hemoglobin, resulting in an O2 concentration of 20% (v/v) (ie, 200 mL O2 per 1 L of blood with a hemoglobin concentration of 150 g/L), assuming normal inspiratory O2 and lung function. Coincidentally, 20% is the same O2 concentration as in the atmosphere. However, within cells, neither the ratio between dissolved and bound O2 nor the relative concentrations and affinity curves of O2-binding proteins are known. Anyway, this is not a problem because it is the pO2 and not the O2 concentration that drives the diffusion of O2 molecules to their targets, such as O2-sensing dioxygenases or O2-reducing cytochrome c oxidase in mitochondria. O2-binding proteins only experience the pO2 and not the O2 concentration. Therefore, life scientists should use pO2 rather than O2 concentration as the preferred unit for biological tissue O2 availability.

What is the pO2 in biological tissues?

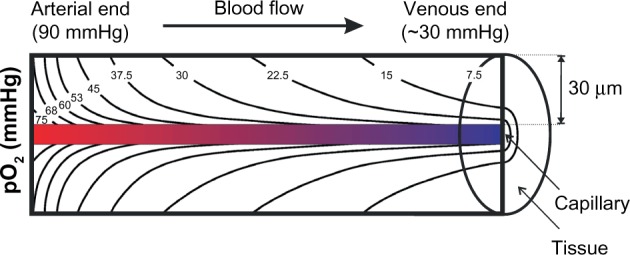

Unfortunately, most of the publications provide single values for the tissue pO2 in different organs, not seldom – and even worse regarding what has been said so far – %O2 concentrations are given. However, life would not be possible if O2 was equally spread throughout the tissue, that is, if neither supply nor sinks existed. Obviously, O2 is unevenly distributed in tissues, forming pO2 gradients. One gradient is found longitudinally along the small blood capillaries (ie, the O2 exchange segments of the blood vessel system) from the arterial to the venous ends. This gradient ranges from ∼90 mmHg in arterial blood to 40 mmHg in mixed venous blood (corresponding to 75% O2 saturation of hemoglobin), but it can also be much lower at the venous end of a capillary if the corresponding tissue has a high O2 extraction capacity such as the heart. Another gradient is formed radially from the O2-delivering hemoglobin to the actual O2 sinks in the mitochondria of O2-consuming cells. Therefore, normal pO2 values distal to the venous end of a capillary can readily be <10 mmHg. The resulting pO2 profiles can be estimated within a cylinder of ∼30 μm radius (ie, half of the average distance between two capillaries) around each blood vessel, the so-called Krogh tissue cylinder (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Krogh’s tissue cylinder.

Notes: Overlapping longitudinal (convective) and radial (diffusive) pO2 gradients form the physiological tissue O2 distribution (calculated isobaric pO2 profiles assuming constant tissue O2 consumption). All cells located within this pO2 profile are considered to be physiologically “normoxic”, despite the highly variable absolute pO2 levels.

How can the tissue pO2 be visualized?

No imaging/measurement technique is currently available to directly assess pO2 profiles within tissues. Infrared (pulse oximetry) and magnetic resonance (blood oxygenation level-dependent [BOLD]) techniques rely on hemoglobin O2 saturation rather than tissue pO2 levels. Polarographic and optical detection methods involve tiny electrodes and glass fibers, respectively, which are pierced into the tissues. Their diameters are minimally ∼20 μm but usually ∼100 μm; obviously still far too large to reliably detect biologically relevant pO2 profiles, not to mention the tissue damage they cause, leading to tissue compression, bleeding, edema, and O2 diffusion/convection along the penetration canal. It is mandatory that histogram distributions over several hundred measurement sites are provided rather than single mean or median tissue pO2 values.14,15

A very popular method to visualize tissue hypoxia, especially in cancer research, is the IV injection of nitroimidazole compounds briefly before the (tumor) tissue is resected.16 A large variety of such compounds exists, including derivatives bearing antibody epitopes (eg, pimonidazole or EF5), positron emission tomography tracers (eg, 18F-fluoromisonidazole), and hypoxia-activated pro-drugs (eg, TH-302).17 A four-electron reduction of these compounds by cellular nitroreductases is required to convert them into reactive species that covalently bind to macromolecules such as proteins and DNA. At pO2 levels above ∼10 mmHg, the first of these four-electron reduction steps – forming a nitro radical anion (RNO2−) – is reversed.17 Therefore, nitroimidazole compounds cannot deliver a detailed map of different pO2 levels but only a “yes-or-no” picture of tissue regions with a pO2 <10 mmHg, which is then often called “hypoxic” even if this represents an oversimplification. Moreover, one should be aware that two-electron nitroreductases, such as DT-diaphorase, can circumvent the O2-sensitive step, leading to false-positive results.

Another emerging technique relies on heme-based probes whose phosphorescent lifetime is quenched by physiological ranges of pO2, that is, the signal is not dependent on probe concentration. While in theory such probes should provide graded maps of pO2 variability, their limited tissue concentrations (they are not enriched in hypoxia areas), considerable costs, and the requirement for specialized microscopy equipment have prevented so far a more widespread application of these probes.18,19

Because of the lack of more appropriate methods, biology-based techniques, such as antibody-mediated detection of the O2-sensitive HIFα subunits and their downstream target genes, are still commonly used to detect “hypoxic” tissue areas. For carbonic anhydrase IX, at least in cancer tissues, probably the most strongly induced HIF target gene, a non-antibody-mediated fluorescent in vivo probe (called HypoxiSense 680) has been developed.20,21 However, at best, these techniques provide only indirect evidence for tissue hypoxia due to self-adaptation,22 “normoxic” regulation, and cell type-specific expression.23 At least the latter point has been circumvented by the generation of transgenic mice ubiquitously and constitutively expressing a luciferase reporter gene fused to the O2-dependent degradation domain of HIF-1α.24 Following the injection of luciferin, hypoxia-dependent bioluminescence can be imaged, which at least partially overlaps with pimonidazole and HIFα immunodetection.25

What is the pO2 in organs?

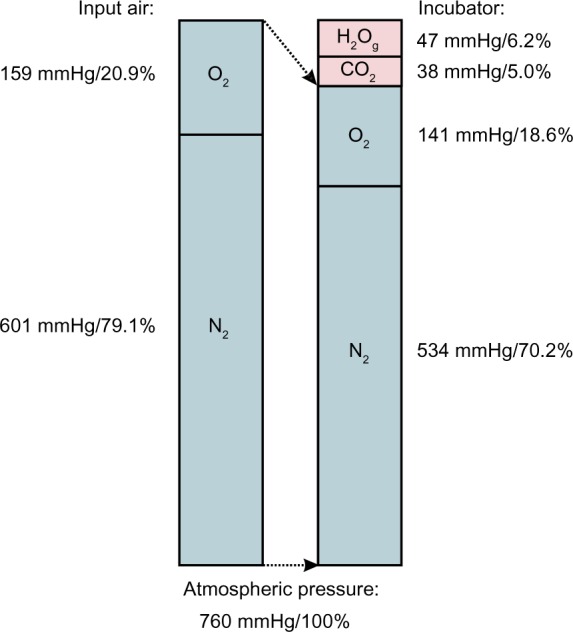

In addition to the general features of tissue pO2 distribution discussed earlier, several organotypic and cell type-specific characteristics must be considered (Figure 5).26,27 Liver and kidney, for instance, display pronounced physiological pO2 gradients,28,29 which can even be visualized by using EF5 or VEGF expression as HIF-1-dependent surrogate marker.30 Lung alveolar epithelium contains the highest pO2 levels as it is oxygenated directly by the inspiratory air. Heavily working skeletal muscle has a large O2 extraction capacity and hence a huge variety of pO2 levels. Cardiomyocytes experience cyclic hypoxia with each heartbeat. Some tissues, such as the avascular cornea of the eye and nucleus pulposus of the intervertebral discs, have a very low pO2 but still must remain blood vessel free. Also central luminal cells of the testicular seminiferous tubuli reside within a very low pO2.31 Finally, some cell types, such as neurons, are strikingly hypoxia-intolerant,32 whereas others, such as certain stem cells, need a hypoxic niche to remain in an undifferentiated stage.33

Figure 5.

Organotypic characteristics in tissue oxygenation and O2 metabolism.

Notes: Combined spatial and temporal processes result in a broad spectrum of physiologically “normoxic” tissue pO2 values. For details see section: What is the pO2 in organs?

What is normoxia, and what is hypoxia?

It may seem peculiar, but nobody has a precise answer to this apparently simple question. Physiological O2 availability is a continuum from lung alveolar pO2 of ∼100 mmHg to functional anoxia at pO2 levels that are below the O2 affinity of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase. Mitochondrial P50 values from 0.06 mmHg to 0.45 mmHg pO2 have been reported, that is, 10–100-fold below the typical intracellular pO2.34 However, the O2-sensing PHD-HIF system ensures that mitochondrial respiration is adapted to decreased oxygenation long before limiting pO2 levels are reached.35 Many cell types do not even need mitochondria for their energy (ATP) production and solely rely on anaerobic glycolysis. Cancer cells usually maintain glycolytic energy metabolism even under high pO2 levels, the so-called aerobic glycolysis or Warburg effect. Therefore, no threshold pO2 level exists, which would define “hypoxia” based on limited mitochondrial respiration.

As outlined in Figure 4, tissue O2 is distributed along the pO2 profiles according to Krogh’s tissue cylinder. All cells residing within this pO2 profile are physiologically “normoxic”. Thus, it does not make sense to define a single pO2 value below which cells are called “hypoxic”. Although 20.9% incubator O2 conditions are usually referred to as “normoxic”, in physiological terms, they are rather “hyperoxic” because not even lung alveolar cells are ever exposed to 20.9% O2. Since the cellular O2-sensing system is self-adaptive,22 cells do not “know” the absolute pO2 levels in their microenvironment. In fact, “hypoxia” is a temporal rather than a spatial term. Every decrease in pO2 that causes a biological effect, for example, a (transient) increase in HIFα protein stability, can be called “hypoxia”.

Conclusion

Considering the discussed principles of biological O2 distribution in vitro and in vivo, it becomes evident that it is quite useless to ask for the “correct” O2 concentration in an incubator to mimic a certain cellular pO2 corresponding to a specific tissue location. For routine experimental work, it is usually acceptable to compare at least two O2 concentrations that are sufficiently different to cause specific biological effects while not affecting general cell viability. In cases where absolute pO2 levels need to be compared, for example, between different laboratories, only the actually measured pericellular pO2 levels but not the adjusted gas phase O2 concentrations in the incubator are relevant.

Acknowledgments

The work of the authors is supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation grant 31003A_146203 (RHW), by the KFSP Tumor Oxygenation of the University of Zurich (RHW), and by the NCCR Kidney.CH (RHW, DH, VK).

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Klinke R, Pape H-C, Kurtz A, Silbernagl S. Physiologie. 3 ed. Stuttgart, Germany: Georg Thieme; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Groebe K, Vaupel P. Evaluation of oxygen diffusion distances in human breast cancer xenografts using tumor-specific in vivo data: role of various mechanisms in the development of tumor hypoxia. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1988;15:691–697. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(88)90313-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olive PL, Vikse C, Trotter MJ. Measurement of oxygen diffusion distance in tumor cubes using a fluorescent hypoxia probe. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1992;22:397–402. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(92)90840-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grimes DR, Kelly C, Bloch K, Partridge M. A method for estimating the oxygen consumption rate in multicellular tumour spheroids. J R Soc Interface. 2014;11:20131124. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2013.1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pettersen EO, Larsen LH, Ramsing NB, Ebbesen P. Pericellular oxygen depletion during ordinary tissue culturing, measured with oxygen microsensors. Cell Prolif. 2005;38:257–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2005.00345.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Metzen E, Wolff M, Fandrey J, Jelkmann W. Pericellular pO2 and O2 consumption in monolayer cell cultures. Respir Physiol. 1995;100:101–106. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(94)00125-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Polak J, Studer-Rabeler K, McHugh H, Hussain MA, Shimoda LA. A system for exposing cultured cells to intermittent hypoxia utilizing gas permeable cultureware. Gen Physiol Biophys. 2015;34:235–247. doi: 10.4149/gpb_2014043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allen CB, Schneider BK, White CW. Limitations to oxygen diffusion and equilibration in in vitro cell exposure systems in hyperoxia and hypoxia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2001;281:L1021–L1027. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.281.4.L1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Newby D, Marks L, Lyall F. Dissolved oxygen concentration in culture medium: assumptions and pitfalls. Placenta. 2005;26:353–357. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiang BH, Semenza GL, Bauer C, Marti HH. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 levels vary exponentially over a physiologically relevant range of O2 tension. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:C1172–C1180. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.271.4.C1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jewell UR, Kvietikova I, Scheid A, Bauer C, Wenger RH, Gassmann M. Induction of HIF-1α in response to hypoxia is instantaneous. FASEB J. 2001;15:1312–1314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jaakkola P, Mole DR, Tian YM, et al. Targeting of HIF-α to the von Hippel-Lindau ubiquitylation complex by O2-regulated prolyl hydroxylation. Science. 2001;292:468–472. doi: 10.1126/science.1059796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ivan M, Kondo K, Yang H, et al. HIFα targeted for VHL-mediated destruction by proline hydroxylation: implications for O2 sensing. Science. 2001;292:464–468. doi: 10.1126/science.1059817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scheid A, Wenger RH, Schäffer L, et al. Physiologically low oxygen concentrations determined in fetal skin regulate hypoxia-inducible factor 1 and transforming growth factor-β3. FASEB J. 2002;16:411–413. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0496fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vaupel P, Höckel M, Mayer A. Detection and characterization of tumor hypoxia using pO2 histography. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9:1221–1235. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koch CJ, Evans SM. Optimizing hypoxia detection and treatment strategies. Semin Nucl Med. 2015;45:163–176. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2014.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kizaka-Kondoh S, Konse-Nagasawa H. Significance of nitroimidazole compounds and hypoxia-inducible factor-1 for imaging tumor hypoxia. Cancer Sci. 2009;100:1366–1373. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01195.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Papkovsky DB, Dmitriev RI. Biological detection by optical oxygen sensing. Chem Soc Rev. 2013;42:8700–8732. doi: 10.1039/c3cs60131e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roussakis E, Spencer JA, Lin CP, Vinogradov SA. Two-photon antenna-core oxygen probe with enhanced performance. Anal Chem. 2014;86:5937–5945. doi: 10.1021/ac501028m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Waschow M, Letzsch S, Boettcher K, Kelm J. High-content analysis of biomarker intensity and distribution in 3D microtissues. Nat Methods. 2012;9:iii–iv. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakajima EC, Laymon C, Oborski M, et al. Quantifying metabolic heterogeneity in head and neck tumors in real time: 2-DG uptake is highest in hypoxic tumor regions. PLoS One. 2014;9:e102452. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stiehl DP, Wirthner R, Köditz J, Spielmann P, Camenisch G, Wenger RH. Increased prolyl 4-hydroxylase domain proteins compensate for decreased oxygen levels. Evidence for an autoregulatory oxygen-sensing system. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:23482–23491. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601719200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stroka DM, Burkhardt T, Desbaillets I, et al. HIF-1 is expressed in nor-moxic tissue and displays an organ-specific regulation under systemic hypoxia. FASEB J. 2001;15:2445–2453. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0125com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Safran M, Kim WY, O’Connell F, et al. Mouse model for noninvasive imaging of HIF prolyl hydroxylase activity: assessment of an oral agent that stimulates erythropoietin production. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:105–110. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509459103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lehmann S, Stiehl DP, Honer M, et al. Longitudinal and multimodal in vivo imaging of tumor hypoxia and its downstream molecular events. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:14004–14009. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901194106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones DP. Intracellular diffusion gradients of O2 and ATP. Am J Physiol. 1986;250:C663–C675. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1986.250.5.C663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vanderkooi JM, Erecinska M, Silver IA. Oxygen in mammalian tissue: methods of measurement and affinities of various reactions. Am J Physiol. 1991;260:C1131–C1150. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1991.260.6.C1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leichtweiss HP, Lübbers DW, Weiss C, Baumgärtl H, Reschke W. The oxygen supply of the rat kidney: measurements of intrarenal pO2. Eur J Physiol. 1969;309:328–349. doi: 10.1007/BF00587756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wenger RH, Hoogewijs D. Regulated oxygen sensing by protein hydroxylation in renal erythropoietin-producing cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2010;298:F1287–F1296. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00736.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marti HH, Risau W. Systemic hypoxia changes the organ-specific distribution of vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:15809–15814. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wenger RH, Katschinski DM. The hypoxic testis and post-meiotic expression of PAS domain proteins. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2005;16:547–553. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cervos-Navarro J, Diemer NH. Selective vulnerability in brain hypoxia. Crit Rev Neurobiol. 1991;6:149–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhu LL, Wu LY, Yew DT, Fan M. Effects of hypoxia on the proliferation and differentiation of NSCs. Mol Neurobiol. 2005;31:231–242. doi: 10.1385/MN:31:1-3:231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gnaiger E, Lassnig B, Kuznetsov A, Rieger G, Margreiter R. Mitochondrial oxygen affinity, respiratory flux control and excess capacity of cytochrome c oxidase. J Exp Biol. 1998;201:1129–1139. doi: 10.1242/jeb.201.8.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fukuda R, Zhang H, Kim JW, Shimoda L, Dang CV, Semenza GL. HIF-1 regulates cytochrome oxidase subunits to optimize efficiency of respiration in hypoxic cells. Cell. 2007;129:111–122. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]