A 66 year old, gravida 4, para 3 African American woman was admitted for repair of an enterocutaneous abdominal fistula, a complication of prior attempts to repair an abdominal hernia. She had a complicated past medical history that included coronary artery disease, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, hypoparathyroidism, asthma and non-insulin-dependent diabetes. Physical examination demonstrated marked obesity and a midline wound in the abdomen that was draining purulent fluid. Local exploration demonstrated an infected polypropylene mesh and soft tissue infection. A blood count revealed a microcytic anemia (Hgb 6.8 gm/dL), hematocrit 22% WBC 9,000 and platelets 329,000/μL. Clopidogrel, which she had been taking for several years, was discontinued and she was started on piperacillin-tazobactam and vancomycin. During surgical correction of the hernia, she was given 3 units of RBCs because of anemia and one unit of platelets because of oozing from the operative site. After surgery, she was given unfractionated heparin for thromboprophylaxis. Her post-operative course was uneventful until Day 8 when she developed scattered petechial hemorrhages on arms, legs and abdomen and hematuria. A blood count showed that her platelet level, which had been 180,000/μL on Day 7, was “zero” (no platelets detected). Examination of a peripheral blood film showed that platelets were absent and RBC morphology was unremarkable. A coagulation panel was normal.

Absence of platelets on inspection of the peripheral blood film rules out pseudo-thrombocytopenia, although this was unlikely in view of her prior normal platelet count and her bleeding symptoms. Largely normal RBC morphology, is a change from her hypochromic microcytosis and reflects a high percentage of transfused RBCs. Decline in platelets from the normal range to the level seen in this patient in less than one day indicates fulminating destruction of platelets in the peripheral blood. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura can cause severe thrombocytopenia, but lack of microangiopathic RBC morphology and evidence for hemolysis argues strongly against this possibility. The normal coagulation panel rules out disseminated intravascular coagulation. Bacterial sepsis can sometimes cause profound thrombocytopenia, but other signs of sepsis were not present so blood cultures were not performed.

In the absence of other explanations for the drop in platelet levels, idiopathic (autoimmune) thrombocytopenia (ITP) was considered and she was started on methyl-prednisolone 60 mg/day.

A diagnostic test equivalent to the direct antiglobulin (Coomb’s) test for autoimmune hemolytic anemia is not available for investigation of ITP but acute ITP of this severity would be extremely unusual in a 66 year-old woman.

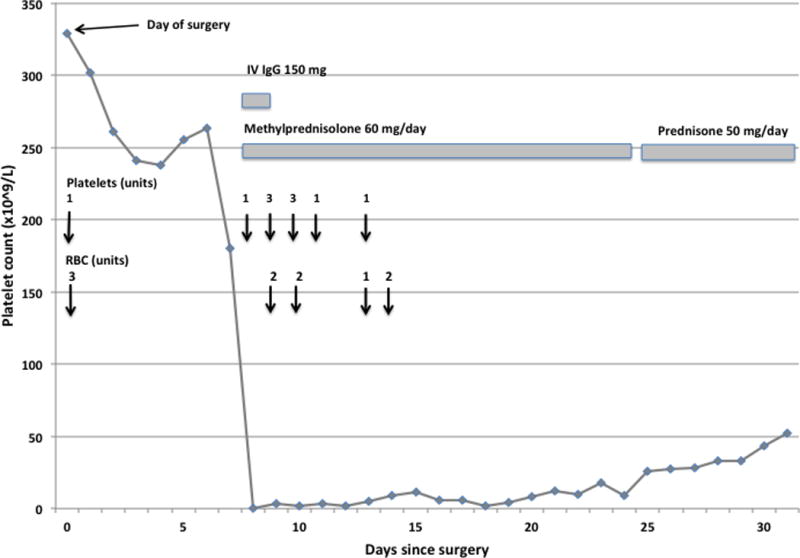

She remained profoundly thrombocytopenic for the next seven days despite corticosteroid therapy, repeated platelet transfusions and a course of IV IgG (Figure 1). Seven units of RBCs were transfused because of persistent gastrointestinal bleeding. The possibility that the patient might have heparin-induced thrombocytopenia was considered. Heparin was discontinued and a solid phase assay for IgG, IgA and IgM antibodies that recognize complexes of heparin and platelet-factor 4 (PF4 ELISA) was performed with negative results.

Figure 1. Clinical course.

Bleeding symptoms developed on Day 8 after surgery when the platelet count was “undetectable.” Vertical arrows indicate transfusions of platelets and/or RBCs. Despite transfusions, corticosteroid and IVIgG treatment, severe thrombocytopenia persisted until Day 24 post-surgery.

HIT should be considered in any patient given heparin who experiences a drop in platelet levels after 3–4 days of heparin exposure. In HIT, however, the platelet decrease is usually mild; indeed, thrombocytopenia as severe as that seen in this patient argues against the diagnosis. A positive PF4/ELISA test is consistent with but not diagnostic of HIT, However, a negative result makes the diagnosis almost untenable.

The possibility that thrombocytopenia might be caused by sensitization to piperacillin-tazobactam or vancomycin was considered. These drugs were discontinued and a blood sample was sent to an outside laboratory to be tested for drug-dependent, platelet-reactive antibodies specific for these drugs. In testing done by flow cytometry [1], a non-drug-dependent platelet antibody was detected. After absorption with platelets, however, no residual antibody that reacted with platelets only when drug was present was identified.

Timing of the thrombocytopenia (7 days after starting medication) is typical for drug-induced immune thrombocytopenia (DITP) and vancomycin and piperacillin are among the most common medications that cause this condition. A profound decrease in the platelet level, as seen in this case, is not unusual in DITP. However, drug-dependent, platelet-reactive antibodies are usually detectable in patients sensitive to these these particular drugs. When DITP is suspected, any medication to which the patient was newly exposed should be discontinued. When necessary, pharmacological equivalents can be safely substituted because drug-dependent antibodies are highly specific for the sensitizing medication.

Further studies showed that that the non-drug-dependent platelet antibody recognized platelets from each of four normal donors. Serum was then tested against a panel of platelets previously typed for human platelet-specific antigens (HPA) using modified antigen capture ELISA, an assay that identifies the glycoprotein targets recognized by platelet-reactive antibodies [1]. Findings showed that multiple antibodies were present. Two were specific for the HPA antigens HPA-1a (PLA1) and HPA-2a (Kob) residing on platelet glycoproteins GPIIIa and GPIb, respectively. Multi-specific class I HLA antibodies were also identified.

It is not surprising to find Class I HLA antibodies in serum of a patient formerly pregnant and heavily transfused eight days before but identification of strong antibodies reactive with two different platelet-specific glycoprotein complexes is highly unusual since these proteins are not highly immunogenic. The HPA-1a and HPA-2a alloantigens are found on platelets of about 98% and 99% of the general population, respectively. Demonstration of alloantibodies specific for these two high frequency antigens in the same individual suggested that the patient must be homozygous for their relatively low frequency alleles.

DNA-based platelet typing [2] confirmed that the patient’s genotype was HPA-1b/b, HPA-2b/b, a combination found in about one in 2,500 African-Americans.

Bleeding symptoms decreased in severity after ten days, but severe thrombocytopenia persisted for three weeks, after which platelets gradually rose to normal levels and remained stable thereafter (Figure 1).

DISCUSSION

This patient received RBCs and platelet transfusions at the time of surgery and was recovering uneventfully until Day 8 when she experienced life-threatening bleeding and was discovered to be profoundly thrombocytopenic. Transfusions and other supportive measures maintained her in a stable condition while diagnostic studies were performed but failed to provide an explanation for persistent destruction of platelets as illustrated by failure of platelet transfusions to elevate the platelet count. Serologic studies eventually demonstrated potent antibodies specific for two high frequency platelet antigens, HPA-1a and HPA-2a and showed that the patient herself was negative for these antigens, indicating an extremely unusual platelet phenotype. Together, the clinical and serologic findings established the diagnosis of post-transfusion purpura (PTP).

PTP, first described in 1961 [3], is characterized by profound thrombocytopenia occurring 5–10 days after a blood transfusion. In the intervening 55 years, hundreds of cases have been reported [4–7]. Most patients achieve remission after 1–4 weeks but about 15% have a fatal outcome. The hallmark of PTP is the presence of potent alloantibodies specific for one or more human platelet-specific antigens (HPA) to which the patient was exposed by transfusion. Antibody is usually specific for the high frequency antigen HPA-1a but many other HPA targets have been identified. It is widely thought that the HPA-specific alloantibody, despite its inability to react with platelets of the patient, are somehow responsible for the thrombocytopenia. Mechanisms suggested to explain how this might be possible include binding to platelets of immune complexes produced when transfused alloantigen reacts with alloantibody [3, 8, 9] and adhesion of transfused alloantigen to autologous platelets, modifying their specificity and making them an antibody target [10, 11]. Both of these mechanisms require transfused alloantigen to remain in the circulation for weeks, a possibility that seems highly unlikely in the presence of a potent alloantibody that would be expected to promote antigen clearance.

Other reports going back more than 30 years have hinted at an alternative explanation for destruction of autologous platelets in PTP - that a platelet-specific autoantibody, produced concomitantly with the characteristic alloantibody might be responsible [8, 12–16]. In several studies, patient platelets were found to be coated with immunoglobulins that disappeared after recovery [8, 12, 13, 17] and in one case were specific for GPIIb/IIIa [13]. A few reports identified antibodies in a blood sample obtained during thrombocytopenia that reacted weakly with autologous platelets obtained post-recovery [12, 16, 18]. Others demonstrated platelet-reactive antibodies in eluates prepared from patient platelets during the thrombocytopenic stage [7–9, 17]. Curiously, several of these eluates appeared to contain antibodies specific for HPA-1a, despite coming from HPA-1a-negative platelets. Evidence for autoantibodies was also obtained by Watkins et al who isolated three distinct clones reactive with all forms of GPIIb/IIIa from a recombinant immunoglobulin library prepared from B cells of a PTP patient [15].

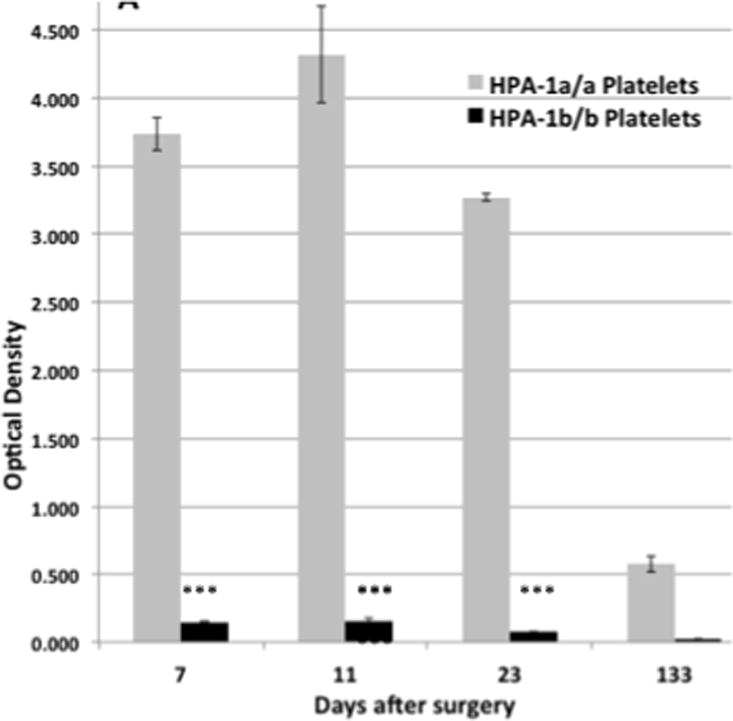

The possibility that PTP is an autoimmune disorder is difficult to study because the potent alloantibodies will mask an underlying autoantibody when normal platelets are used as targets and because autologous platelets are hard to obtain in quantity when the patient is profoundly thrombocytopenic. In the case described here, multiple patient blood samples, albeit limited in quantity, were available from dates throughout the period of thrombocytopenia and autologous platelets were obtained after recovery, providing a unique opportunity to test reactions of patient serum obtained at various time points against platelets from normal persons and the patient herself. As shown in Figure 2, the HPA-1a alloantibody was present on Day 7 when the platelet level was 180 × 109/L, persisted until platelet recovery began and was still present on day 133, more than 3 months after platelet recovery. The HPA-2a-specific antibody was also present on days 7, 11 and 23 but was not detected in the post-recovery sample (data not shown).

Figure 2. Identification of platelet-reactive alloantibodies using modified antigen ELISA (MACE).

Using a GPIIb/IIIa-specific capture antibody, an IgG antibody that recognized HPA-1a/a but not HPA-1b/b platelets was detected on days 7, 11, 23 and 133. An HPA-2A-specific antibody reactive with GPIb was similarly demonstrated on Days 7, 11 and 23, but not on Day 133 (not shown). Brackets denote mean of triplicate determinations + 1.0 SD.

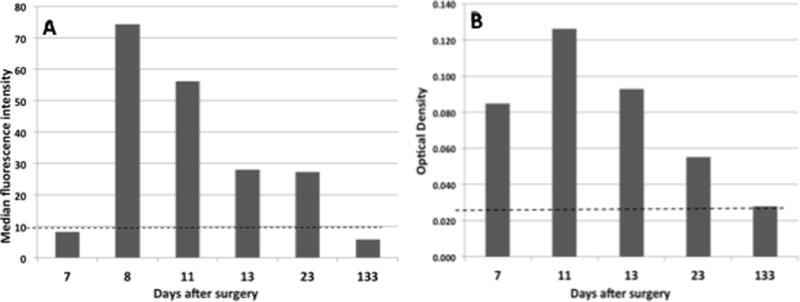

The possibility that platelet destruction in this patient may have been caused by an autoantibody was examined by studying the reactions of various serum samples against autologous post-recovery platelets. Using flow cytometry, auto-reactivity was not detected on Day 7 when platelets were declining, but still within the normal range (180 × 109/L) or post-recovery on Day 133, but was present on Day 8 when platelets were “undetectable” and on Days 11, 13 and 23 while thrombocytopenia persisted (Figure 3A). Using the glycoprotein-specific MACE assay, reactivity against autologous GPIIb/IIIa was found in samples from Days 7, 11, 13 and 23 but not in post-recovery serum (Figure 3B). Insufficient quantities of patient serum and platelets were available to study reactions against autologous GPIbα in MACE. At 1:5 dilution, autoantibody was not detected in any of the patient samples using either flow cytometry or MACE. The findings provide strong evidence that platelet destruction was caused by a GPIIb/IIIa-specific autoantibody produced simultaneously with or shortly after the two potent alloantibodies. Relatively weak reactions of autoantibody against autologous platelets (Figures 3A, 3B) are probably a consequence of continuous auto-absorption by platelets newly released from the bone marrow.

Figure 3. Identification of a platelet-reactive autoantibody using flow cytometry and MACE.

A) Using autologous platelets as targets, an IgG autoantibody was detected by flow cytometry on Days 8, 11, 13, and 23 after surgery, but not on Days 7 and 133. Bars denote mean value of duplicate determinations. Horizontal line depicts mean value obtained with normal serum + 3.0 SD. B) An IgG antibody reactive with autologous GPIIb/IIIa in MACE was detected on Days 7, 11, 13, and 23 post-surgery. Bars denote mean value of duplicate determinations and horizontal line indicates mean value obtained with normal serum + 3.0 SD.

Although PTP is uncommon, it has been known for many years that RBC-specific autoantibodies are not rare in patients mounting an immune response against an RBC alloantigen [19–21]. In such cases, auto-hemolysis is usually mild and may even be subclinical [19, 21]. However, life-threatening sequelae have been described [21, 22]. By analogy with this phenomenon, well-recognized by RBC serologists, our findings suggest that PTP is a consequence of autoimmunity underlying the allo-response against an HPA antigen. In the case of RBCs, the consequences of the autoimmune response is usually minor because of the large mass of circulating cells for which antibody is specific. With platelets, the consequences can be much more severe because of the small volume of cells targeted (total body platelet mass about 12 ml).

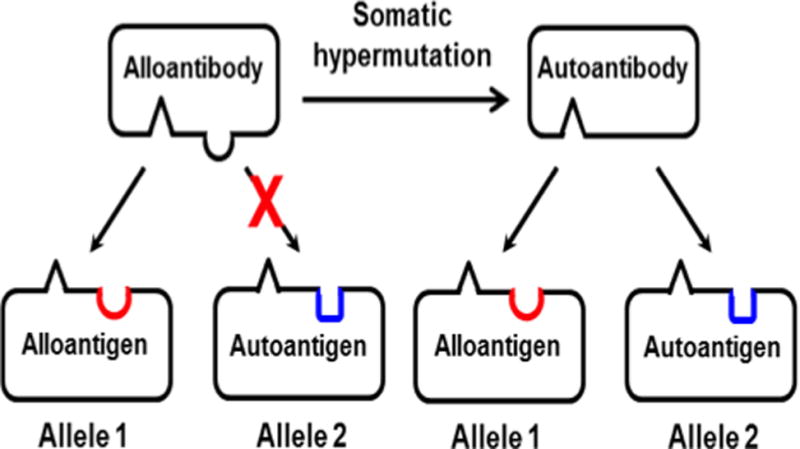

Antibodies raised against alloantigens are unique in that they usually recognize a single amino acid difference that distinguishes the targeted glycoprotein from its autologous counterpart. Although recognition of the amino acid that governs the polymorphism is critical for antibody binding, interactions between alloantibody and non-polymorphic (autologous) amino acid residues in the contact area also contribute importantly to the binding energy [23, 24]. An important aspect of any humoral immune response is somatic hypermutation, in which amino acids that make up the antigen combining site of the B cell receptor (BCR) complementarity determining region (CDR) are randomly mutated and BCRs with increased affinity for antigen are selected for expansion [25]. In an allo-response, mutation of a single, or very small number of nucleotides encoding antibody CDR could, in theory, modify CRD composition in such a way that antibody no longer requires the amino acid defining the alloantigen for target recognition but still recognizes adjacent, non-polymorphic amino acid residues, making it unable to distinguish between alloantigen and its autologous counterpart. One of many possible ways in which this could occur is illustrated schematically in Figure 4. We suggest that random mutations modifying antibody CDR could explain autoantibody production in patients mounting an alloimmune response to a transfused platelet or RBC alloantigen.

Figure 4. Scheme illustrating transition from an alloimmune to an autoimmune response.

Left: “Alelle 1” represents an allelic form of the immunizing glycoprotein. Red half circle represents the polymorphic amino acid (AA) that defines the immunizing alloantigen. Alloantibody recognizes Allele 1 but not the autologous allele (“Allele 2”), which has a different AA (blue) at the polymorphic site. Right: by chance, somatic hypermutation in a proliferating B cell modifies the complementarity-determining region (CDR) of alloantibody so that it no longer requires the AA that defines Allele 1 for binding. The resulting (“mutant”) autoantibody binds equally well to both alleles. Additional mutations (not shown) could enhance antibody binding to adjacent non-polymorphic AAs and favor proliferation of B cells secreting “autoantibody.”

If further studies show that destruction of platelets by autoantibodies in PTP is a general phenomenon, this will provide added justification for use of corticosteroids and agents such as IV IgG and rituximab in patients who experience prolonged thrombocytopenia and/or have intractable bleeding symptoms and will strengthen the rationale for use of plasma exchange transfusion, a treatment shown to be highly effective in some of the early reported cases of PTP [26].

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Curtis BR, McFarland JG. Detection and identification of platelet antibodies and antigens in the clinical laboratory. Immunohematology. 2009;25:125–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peterson JA, Pechauer SM, Gitter ML, et al. New platelet glycoprotein polymorphisms causing maternal immunization and neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia. Transfusion. 2012;52:1117–1124. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2011.03428.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shulman NR, Aster RH, Leitner A, et al. Immunoreactions involving platelets. V. Post-transfusion purpura due to a complement-fixing antibody against a genetically controlled platelet antigen. A proposed mechanism for thrombocytopenia and its relevance in “autoimmunity”. J Clin Invest. 1961;40:1597–1620. doi: 10.1172/JCI104383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vogelsang G, Kickler TS, Bell WR. Post-transfusion purpura: a report of five patients and a review of the pathogenesis and management. Am J Hematol. 1986;21:259–267. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830210305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shtalrid M, Shvidel L, Vorst E, et al. Post-transfusion purpura: a challenging diagnosis. Isr Med Assoc J. 2006;8:672–674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Menis M, Forshee RA, Anderson SA, et al. Posttransfusion purpura occurrence and potential risk factors among the inpatient US elderly, as recorded in large Medicare databases during 2011 through 2012. Transfusion. 2015;55:284–295. doi: 10.1111/trf.12782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kroll H, Kiefel V, Mueller-Eckhardt C. [Post-transfusion purpura: clinical and immunologic studies in 38 patients] Infusionsther Transfusionsmed. 1993;20:198–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.von dem Borne AE, van der Plas-van Dalen CM. Further observation on post-transfusion purpura (PTP) Br J Haematol. 1985;61:374–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1985.tb02838.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taaning E, Skov F. Elution of anti-Zwa (-PIA1) from autologous platelets after normalization of platelet count in post-transfusion purpura. Vox Sang. 1991;60:40–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.1991.tb00869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kickler TS, Ness PM, Herman JH, et al. Studies on the pathophysiology of posttransfusion purpura. Blood. 1986;68:347–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dieleman LA, Brand A, Claas FH, et al. Acquired Zwa antigen on Zwa negative platelets demonstrated by western blotting. Br J Haematol. 1989;72:539–542. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1989.tb04320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taaning E, Tonnesen F. Pan-reactive platelet antibodies in post-transfusion purpura. Vox Sang. 1999;76:120–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kiefel V, Schonberner-Richter I, Schilf K. Anti-HPA-1a in a case of post-transfusion purpura: binding to antigen-negative platelets detected by adsorption/elution. Transfus Med. 2005;15:243–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3148.2005.00578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Welling KL, Taaning E, Lund BV, et al. Post-transfusion purpura (PTP) and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) Eur J Haematol. 2003;71:68–71. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0609.2003.00092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Watkins NA, Smethurst PA, Allen D, et al. Platelet alphaIIbbeta3 recombinant autoantibodies from the B-cell repertoire of a post-transfusion purpura patient. Br J Haematol. 2002;116:677–685. doi: 10.1046/j.0007-1048.2001.03301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Minchinton RM, Cunningham I, Cole-Sinclair M, et al. Autoreactive platelet antibody in post transfusion purpura. Aust N Z J Med. 1990;20:111–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.1990.tb01284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pegels JG, Bruynes EC, Engelfriet CP, et al. Post-transfusion purpura: a serological and immunochemical study. Br J Haematol. 1981;49:521–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1981.tb07260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woelke C, Eichler P, Washington G, et al. Post-transfusion purpura in a patient with HPA-1a and GPIa/IIa antibodies. Transfus Med. 2006;16:69–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3148.2005.00633.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ness PM, Shirey RS, Thoman SK, et al. The differentiation of delayed serologic and delayed hemolytic transfusion reactions: incidence, long-term serologic findings, and clinical significance. Transfusion. 1990;30:688–693. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1990.30891020325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Young PP, Uzieblo A, Trulock E, et al. Autoantibody formation after alloimmunization: are blood transfusions a risk factor for autoimmune hemolytic anemia? Transfusion. 2004;44:67–72. doi: 10.1046/j.0041-1132.2003.00589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garratty G. Autoantibodies induced by blood transfusion. Transfusion. 2004;44:5–9. doi: 10.1111/j.0041-1132.2004.00658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sigler E, Shvidel L, Yahalom V, et al. Clinical significance of serologic markers related to red blood cell autoantibodies production after red blood cell transfusion-severe autoimmune hemolytic anemia occurring after transfusion and alloimmunization: successful treatment with rituximab. Transfusion. 2009;49:1370–1374. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2009.02163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang TY, Siegel DL. Genetic and immunological properties of phage-displayed human anti-Rh(D) antibodies: implications for Rh(D) epitope topology. Blood. 1998;91:3066–3078. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bougie DW, Peterson JA, Kanack AJ, et al. Transfusion-related acute lung injury-associated HNA-3a antibodies recognize complex determinants on choline transporter-like protein 2. Transfusion. 2014;54:3208–3215. doi: 10.1111/trf.12717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peled JU, Kuang FL, Iglesias-Ussel MD, et al. The biochemistry of somatic hypermutation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2008;26:481–511. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cimo PL, Aster RH. Post-transfusion purpura: successful treatment by exchange transfusion. N Engl J Med. 1972;287:290–292. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197208102870608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]