Abstract

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) is one of the commonest forms of early-onset dementia, accounting for up to 20% of all dementia patients. Recently, it has been shown that mutations in progranulin gene (PGRN) cause many familial cases of FTD. Members of a family affected by FTD spectrum disorders were ascertained in Poland and Canada. Clinical, radiological, molecular, genetic, and pathological studies were performed. A sequencing analysis of PGRN exons 1–13 was performed in the proband. Genotyping of the identified PGRN mutation and pathological analysis was carried out in the proband’s brother. The onset of symptoms of FTD in the proband included bradykinesia, apathy, and somnolence followed by changes in personality, cognitive deficits, and psychotic features. The proband’s clinical diagnosis was FTD and parkinsonism (FTDP). DNA sequence analysis of PGRN revealed a novel, heterozygous mutation in exon 11 (g.2988_2989delCA, P439_R440fsX6). The mutation introduced a premature stop codon at position 444. The proband’s brother with the same mutation had a different course first presenting as progressive non-fluent aphasia, and later evolving symptoms of behavioral variant of FTD. He also developed parkinsonism late in the disease course evolving into corticobasal syndrome. Pathological analysis in the brother revealed Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration-Ubiquitin (FTLD-U)/TDP-43 positive pathology. The novel PGRN mutation is a disease-causing mutation and is associated with substantial intra-familial clinical heterogeneity. Although presenting features were different, rapid and substantial deterioration in the disease course was observed in both family members.

Keywords: Corticobasal syndrome, frontotemporal dementia, haploinsufficiency, parkinsonism, progranulin mutation, progressive non-fluent aphasia

INTRODUCTION

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) is a clinically, genetically, and neuropathologically heterogeneous disorder, accounting for 20% of early-onset dementia [1, 2]. FTD is characterized by behavioral and language dysfunction, without amnesia, and consensus clinical and pathological diagnostic criteria have been proposed [1,3–5].

Progranulin gene (PGRN, GRN [OMIM 138945]) mutations were shown to be common in sporadic and familial FTD [6–8]. PGRN is a 593 amino acid glycoprotein, composed of 7.5 evolutionary conserved tandem repeats, which are cleaved, forming a family of granulin peptides. It is a growth factor important in neural development [9]. A haploinsufficiency mechanism was identified to be the etiology underlying PGRN-associated neurodegeneration, which causes frontotemporal lobar degeneration with ubiquitin-positive, tau-negative inclusions (FTLD-U) [6,7]. TDP-43 was found to be the major pathological protein underlying FTLD-U pathology [10].

From a clinical perspective, there is much to learn about how specific symptoms of FTD map onto FTLD pathological subtypes. PGRN mutations have been associated with substantial phenotypic heterogeneity in clinical presentation with a variety of diagnoses being observed: behavioral variant FTD (bvFTD), progressive non-fluent aphasia (PNFA), corticobasal syndrome (CBS), Alzheimer’s disease, parkinsonism, and FTD with Parkinson’s (FTDP) [11–16]. This clinical heterogeneity results from the same PGRN mutation causing pathology in different hemispheres and lobar regions [14]. The molecular mechanism underlying this clinical variability in different family members is unknown.

In this report, we describe the clinical, neuropsychological, and radiographic features at onset and longitudinally in two brothers from the first Polish kindred identified to have a novel PGRN mutation. Pathological characterization was performed in the index case’s brother.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Genealogical data was ascertained in Poland. The proband was living in Warszawa, Poland. His brother was living in Toronto, Canada. They underwent assessment in specialized dementia clinics. Clinical evaluation included history, physical examination, and cognitive screening. Routine biochemical screening was done. Brain MRI and SPECT were performed. Neuropsychological, neuropsychiatric, and functional measures were completed. Baseline and ten month follow-up data are presented for the brother.

The case-control group for genetic analysis consisted of 90 patients with familial or sporadic FTD (age-matched) and 200 elderly, neurologically healthy controls from the Polish population. All participants or their relatives provided written, informed consent in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and the study was approved by the appropriate ethics committees.

Genetic analysis

DNA was isolated from peripheral leukocytes using standard procedures [17]. Intronic primers were used to amplify and sequence all (1–13) PGRN exons [6,7]. Additionally, all exons of MAPT and PSEN1 were amplified and sequenced to exclude mutations or rare polymorphisms [17,18]. Amplification products were purified with ExoSAP IT (USB) and sequencing was carried out using the BigDye Terminator v1.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems) and the ABI PRISM 3130 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). RNA was extracted from the proband’s leukocytes using TRIzol reagent (Ambion) according to manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA prepared from 5 μg of RNA using Superscript II (Invitrogen) was used as a template for quantitative PCR with Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix on an ABI PRISM 7500 instrument (Applied Biosystems) according to manufacturer’s’ protocols. Relative 2-ΔΔCt method with ACTB as a reference gene was used to estimate levels of PGRN mRNA. Primers were designed for PGRN cDNA: forward 5′-ATCCAGAGTAAGTGCCTCTCCAA-3′, reverse 5′-C TCACCTCCATGTCACATTTCAC-3′, and for ACTB: 5′-CCGCAAAGACCTGTACGCCA-3′ and 5′-TGGA CTTGGGAGAGGACTGG-3′.

Absence of mutated mRNA was confirmed using the PCR method with reverse primer specific for the frameshifted region (5′-GTCTGCTGCTCGGACCAC-3′ and 5′-GTCACAGCCGATGTCTCG-3′). Absence of the mutation in the case-control groups was confirmed using restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis with AvaI (Fermentas) or direct sequencing.

Neuropathological analysis

Paraffin-embedded sections were stained with haematoxylin and eosin, Luxol fast blue, Bielschowski and Gallyas. Immunostains using commercial antibodies for tau (Dako, A0024), ubiquitin (Vector Labs, ZPU576), α-synuclein (Vector Labs), and subsequently with TDP-43 (ProteinTech Group, Inc.) were performed.

RESULTS

Clinical, neuropsychological, and radiographic features

Proband (III:1)

The proband was a 65-year-old right-handed male with no medical history. He had 16 years of education and worked as a managing director of a company. At age 62, the first symptoms were slowness, apathy and somnolence. The patient became withdrawn, less talkative, gave up hobbies and had trouble handling familiar objects. After several months, his social judgment deteriorated with a breakdown in formalities. He became disinhibited and significant personality changes were observed. He developed cognitive symptoms thereafter including aphasia and memory impairment.

Two years later (age 64), he stopped working and driving. Urinary incontinence occurred. The patient underwent neurologic assessment and had evidence for dementia and parkinsonism. Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) was 20. The patient deteriorated rapidly over the next few months with insomnia and psychotic symptoms. He had significant irritability when opposed. Motor re-examination showed moderately impaired monotone, slurred speech; minimal hypomimia; resting tremor of upper extremities, moderate in amplitude; moderate rigidity; severe motor slowness and multi-step turning with postural instability. The symptoms progressed throughout the ensuing observation period.

Neuropsychological assessment (age 64) showed impairment of executive functions, speech, attention, and visuospatial functions (Table 1, III:1). He had spared autobiographical memory. Word-finding difficulties were pronounced both in spontaneous speech and in verbal fluency tasks with perseverations. He had problems switching between categories. The proband’s verbal learning was impaired, with a flat, plateau-like curve, and with intact delayed memory. Working memory was severely disturbed. Copy of the Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure was disorganized with visuospatial and perseverative errors; most details were omitted on its delayed reproduction. Naming and visual gnosis was intact. The patient had problems with gesture and spatial praxis because of difficulties in motor switching. Sequencing of motor learning was severely impaired with perseverations. This was also manifest as disturbed reciprocal coordination with a strong tendency to repeat only one motor action without inhibition. The patient required help in dressing and showering, and falls occurred daily. The patient manifested loss of initiative and a lack of interest in daily routine activities. He had difficulties with speech and his handwriting became illegible. Psychiatric examination showed psychotic features, including visual hallucinations (faces on windows), bizarre delusions, and misidentifications.

Table 1.

Raw scores on neuropsychological and functional measures for proband (III:1) and proband’s brother (III:2)

| III:2 Session1 | III:2 Session 2 | III:1 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age of Onset (years) | 55 | – | 62 |

| Age at testing (years) | 57 | 58 | 64 |

| Duration of disease at testing (years) | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| Years of education | 18 | – | 16 |

| Neuropsychological Battery and Functional Measures (Test name/Maximum raw score) | |||

| General cognition | |||

| Folstein’s Mini-Mental Status Examination/30 | 19** | 9** | 22** |

| Mattis Dementia Rating Scale/144 | 96** | N/T | N/A |

| Blessed Information, Memory and Concentration Scale/37 | N/A | N/A | 32 |

| Memory | |||

| California Verbal Learning Test - Long Delay Free Recall/16 | 1** | N/T | N/A |

| Delayed Visual Reproduction/41 | 0** | N/T | N/A |

| Auditory verbal learning of 10 words list/First attempt/last attempt/delayed reproduction | N/A | N/A | 4/6/5 |

| Rey Osterieth Complex Figure – reproduction/36 | N/A | N/A | 6** |

| Address item from BIMC/5 | N/A | N/A | 2 |

| Language | |||

| Western Aphasia Battery – total/100 | 67.8** | 40.4** | N/A |

| Western Aphasia Battery – Aphasia Category | Anomic | Broca’s | N/A |

| Western Aphasia Battery – Spontaneous Speech Content | 7** | 2** | N/A |

| Western Aphasia Battery – Spontaneous Speech Fluency | 5** | 1** | N/A |

| Western Aphasia Battery – comprehension/10 | 7.9** | 5.8** | N/A |

| Western Aphasia Battery – Repetition/10 | 8.4** | 6.9** | N/A |

| Western Aphasia Battery – Naming/10 | 5.6** | 4.5** | N/A |

| Boston Naming/30 | 13** | N/T | N/A |

| Boston Naming/20 | N/A | N/A | 20 |

| Semantic Fluency | 6* | 1** | 10* |

| Praxis | |||

| Western Aphasia Battery – praxis/60 | 52** | 34** | N/A |

| Praxis of gesture/5 | N/A | N/A | 4* |

| Reciprocal coordination I/10 II/10 | N/A | N/A | 5 10* |

| Motor sequences learning I/5 II/5 | N/A | N/A | 3 2 |

| Attention and working memory | |||

| Digit span – forward/12 | 6 | N/T | 4* |

| Digit span – backward/12 | 3* | N/T | 3* |

| Serial 7’s test/14 | N/A | N/A | 1** |

| Visuospatial abilities | |||

| Rey Osterieth Complex Figure – copy/36 | 36 | 26.5 | 28 |

| Benton Line Orientation/30 | 28 | 22 | N/A |

| Visual gnosis/17 | N/A | N/A | 14 |

| Executive functions | |||

| Phonemic fluency (F-, A-, S-words) | 3** | N/T | N/A |

| Phonemic fluency (K-words) | N/A | N/A | 2** |

| Wisconsin Card Sort Test – categories/6 | 1** | N/T | N/A |

| Wisconsin Card Sort Test – perseverative errors | 40** | N/T | N/A |

| Activities of daily living | |||

| Disability Assessment for Dementia (%) | 96 | 24** | N/A |

| Neuropsychiatric symptoms | |||

| Neuropsychiatric Inventory – total/144 | 4** | 14** | 23** |

| Neuropsychiatric Inventory – delusions/12 | 0 | 0 | 2** |

| Neuropsychiatric Inventory – hallucinations/12 | 0 | 0 | 6** |

| Neuropsychiatric Inventory – euphoria/12 | 2** | 4** | 0 |

| Neuropsychiatric Inventory – anxiety/12 | 0 | 0 | 2** |

| Neuropsychiatric Inventory – apathy/12 | 2** | 4** | 6** |

| Neuropsychiatric Inventory – depression/12 | 0 | 0 | 1** |

| Neuropsychiatric Inventory – disinhibition/12 | 0 | 2** | 2** |

| Neuropsychiatric Inventory – Irritability/12 | 0 | 0 | 4** |

| Neuropsychiatric Inventory – appetite/12 | 0 | 4** | 0 |

| Cornell Depression Scale (%) | 8 | 3 | 11 |

Session 2 scores were obtained 10 months after session 1 scores for III:2. Unmarked scores are normal based on comparison to healthy population matched for age and years of education.

Borderline-Impaired;

Impaired;

N/T = Not testable; N/A = Not available.

He was diagnosed with FTDP based on neurologic, psychiatric, physical, and neuropsychological examinations. Brain MRI and SPECT results supported this diagnosis and correlated with his symptoms and findings (Fig. 3). Specifically, there was atrophy in the right anterior temporal region and bifrontally, more prominent on the right. There was reduced perfusion bifrontally, more prominent on the right and extending into the right superior parietal region.

Fig. 3.

T1-weighted brain MRI and corresponding 99mTc-HMPAO (800MBq) brain SPECT images of proband (III:1) in standard radiographic axial orientation. Bilateral frontal and temporal regions demonstrate significant atrophy with ventricular enlargement seen on axial slices of T1 weighted images in MRI. Corresponding axial images of functional SPECT showing perfusion defect in frontal and temporal regions, bilaterally. There was a predilection for the right hemisphere both in terms of atrophy and perfusion deficits. Orange-yellow color represents areas of normal perfusion on SPECT, while blue-purple color represents relative decreases in perfusion. AT=anterior temporal; PT=posterior temporal; O=occipital; IF=inferior frontal; IP=inferior parietal; SF=superior frontal; SP=superior parietal.

Proband’s brother (III:2)

The proband’s brother was a right-handed male with no relevant medical history. He was assessed at age 57. He spoke Polish and English fluently. He had 18 years of education. Two years prior, he first presented with the insidious onset and gradual decline in speech fluency; he had frequent word-finding difficulties that interrupted verbal output. He often reverted to his native tongue. Comprehension was intact. However, he continued to work as an engineer.

MMSE was 22/30. Spontaneous speech revealed word-finding difficulties with no paraphasic errors. Comprehension, repetition, naming, and reading were intact. A written description of the Cookie Theft Picture revealed use of simplified sentences with a sparse, but accurate description. There was mild impairment in working memory and executive functions. His neurological exam was normal except for mild increase in tone in the right arm with contralateral limb activation. The initial diagnosis was progressive non-fluent aphasia (PNFA).

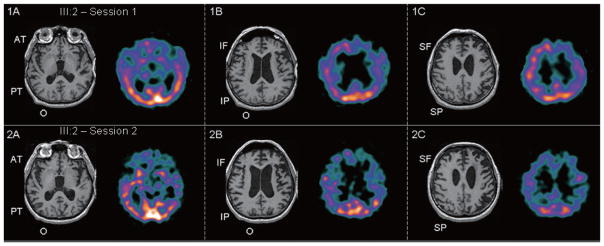

Four months later, neuropsychological testing revealed moderate impairments in most domains with relative sparing of visuospatial and visuoconstructive tasks (Table 1, session 1, III:2). On the Western Aphasia Battery (WAB), his category was anomic. The aphasia over-estimated his deficits. He, however, remained independent functionally with only minor troubles having a phone conversation and taking messages. Initial MRI revealed bilateral frontal > anterior temporal atrophy, which was prominent on the left (Fig. 1A, B, C). Corresponding brain SPECT revealed left > right bifrontal hypoperfusion extending into the left parietal region (Fig. 1B, C).

Fig. 1–2.

T1-weighted brain MRI and corresponding 99mTc-ECD brain SPECT images of proband’s brother (III:2) in radiographic axial orientation. Asymmetric atrophy on MRI is seen affecting the left frontal > parietal regions with ventricular enlargement (III:2 – Session 1) which progresses as seen in Fig. 2 (III:2 – Session 2). Perfusion deficits in the left > right frontoparietal regions in Fig. 1 (III:2 – Session 1) also progress to more bilateral involvement along with left temporal involvement seen in Fig. 2 (III:2 – Session 2). Orange/yellow color represents areas of normal perfusion on SPECT, while blue/purple color represents relative decreases in perfusion. AT = anterior temporal; PT = posterior temporal; O = occipital; IF = inferior frontal; IP = inferior parietal; SF = superior frontal; SP = superior parietal.

Clinical assessment seven months later (age 58) revealed deterioration in multiple spheres of cognition, behavior and function. He perseverated and had difficulties shifting sets. He giggled excessively. He ate quickly cramming food into his mouth and pocketing it in his cheeks. He developed a craving for chocolate. He became disinhibited and impulsive. He stopped maintaining oral hygiene and had trouble eating with utensils. He had difficulties arising from a chair and climbing stairs. His gait was slow with decreased arm swing on the right. Formal testing of praxis revealed both conceptual and ideomotor deficits. His score on the Frontal Behavioral Inventory was 29, above the cutoff indicating FTD. The diagnosis remained PNFA, but his syndrome evolved to include bvFTD.

Prospective re-evaluation on neuropsychological testing ten months after his first session revealed significant deterioration (Table 1, session 2, III:2). MMSE was 9/30. WAB category indicated a Broca’s aphasia. He remained within normal limits on visuospatial tasks. From the neuropsychiatric perspective, there was evidence for euphoria, disinhibition, apathy, and appetite dysregulation. A repeat brain MRI demonstrated worsening atrophy of left > right frontotemporoparietal regions (Fig. 2A–C).

He became incontinent. He spoke with one word at a time. He was unable to follow instructions. He required constant supervision. Physical exam revealed worsening parkinsonism with hypomimia, right > left rigidity, difficulties arising from a chair, decreased right arm swing, stooped posture and festinating gait. Re-evaluation on SPECT revealed progressive global perfusion deficits with occipital sparing (Fig. 2A–C). With the emergence of an asymmetric akinetic-rigid syndrome associated with apraxia, his final diagnosis evolved to include CBS. Eventually, he progressed to full mutism. At age 60, he was bed-ridden. He developed progressive dysphagia. He passed away six years after disease onset (age 61) from complications due to his neurodegeneration.

Neuropathology (III:2)

The brain weighed 1,230 grams. Macroscopic examination disclosed atrophy of the frontal lobes, worse on the left. Temporal and left parietal involvement was present. There was atrophy of the caudate head.

Microscopic examination revealed severe pan-cortical atrophy, worse in anterior frontal regions with microvacuolization. There was cell loss, gliosis, and pallor of the subcortical white matter. Ubiquitin-positive threads co-localized with the microvacuolar changes. Many neurons displayed “comma”-shaped perinuclear inclusions. Rare ubiquinated intranuclear inclusions were demonstrable. Ubiquinated inclusions were abundant in the cingulum, mesiofrontal lobe, precentral gyrus, temporal and parietal lobes, but less so in the latter with segmentally spared areas. A dramatic decrease in ubiquitin pathology was noted in transition from the precentral to postcentral gyrus. Primary visual cortex was spared. Silver stain and immunostaining for tau and α-synuclein was negative.

Subcortical grey matter revealed neuronal ubiquinated granular and filamentous inclusions in caudate, putamen, thalamus, posterior hypothalamus and nucleus accumbens. Globus pallidus and nucleus basalis of Meynert were spared. In limbic regions, the cornu ammonis of CA1 was severely gliotic and shrunken. Microvacuolar changes involving the parahippocampal gyrus were noted, with sparing of the perirhinal cortex. Ubiquitin positive inclusions were observed in neurons of the fascia dentata.

The anterior 1/3 of the cerebral peduncles bilaterally was degenerated. The midbrain was small. Estimated cell loss in the substantia nigra was 60% with severe gliosis and macrophages present. There was no immunostaining for tau or α-synuclein. The pons was small with pallor of the descending tracts. In the medulla, there was no α-synuclein staining. Rare neurons in the inferior olive contained filamentous ubiquinated inclusions. Medullary motor nuclei were intact with no ubiquinated inclusions observed. The cerebellum was unremarkable. Motor neurons in the spinal cord were not affected.

Autopsy sections were re-examined with immunostains for TDP-43 (Fig. 4). TDP-43 positive neuropil threads, neuronal cytoplasmic stippled staining, neuronal cytoplasmic filamentous inclusions, glial [oligo] cytoplasmic and neuronal intranuclear inclusions were found in the frontal cortex, anterior striatum, fascia dentata, substantia nigra, and CA1 region. Final pathological diagnosis was FTLD-U/TDP-43 proteinopathy.

Fig. 4.

Micrographs demonstrating a large number of TDP-43 inclusions (neuropil threads, neuronal cytoplasmic stippled staining, neuronal cytoplasmic filamentous inclusions, glial [oligo] cytoplasmic and neuronal intranuclear inclusions) found in the fascia dentata, substantia nigra, and CA1 region.

Family history

There was a strong family history of early-onset dementia and parkinsonism, suggesting autosomal dominant inheritance (Fig. 5). The proband’s mother (II:2) died at age 64, with a surmised progressive aphasia. Age of onset was 60. The maternal aunt had parkinsonism and dementia and died ca. 65 years (II:3). The proband’s father (II:1) was neurologically intact and died at age 62 of lung cancer.

Fig. 5.

Detection of PGRN mutation P439_R440fsX6. A) Pedigree showing family history of neurodegenerative condition. Black symbols: patients affected with FTD and neurodegeneration; white symbols: unaffected individuals or individuals with no clinical diagnosis available. B) Electropherogram showing start of deletion marked with an arrow. The resulting PGRN mutation P439_R440fsX6 is shown at the bottom of the chromatogram of the proband and his affected brother.

Genetic analysis

A novel PGRN dinucleotide deletion in exon 11 (g.2988_2989delCA, c.1536_1537delCA, P439_R440fs X6) was identified in the proband and his affected brother (Fig. 5). Both the sense and the complementary DNA strand were sequenced. The mutation causes a frameshift at codon 441, and introduces a stop codon at position 444. The mutation was absent in a group of 90 Polish patients with FTD (mean age = 59.7 ± 13 years) and 200 ethnically matched neurologically healthy controls (mean age = 72.7 ± 7 years; MMSE ≥ 28).

RT-PCR analysis of PGRN mRNA levels in peripheral leukocytes from the proband revealed a two-fold decrease of the cDNA transcript as compared to controls without the mutation. PCR using a primer specific to the mutant cDNA resulted in absence of amplification product (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Amplification from genomic DNA (gDNA; lane 1) using primers specific for the mutant allele demonstrate the mutant fragment of 153 bp as expected. Amplification from cDNA (lane 2) shows an absence of the expected product supportive of non-sense mediated decay. Ladder: GeneRuler 1kb DNA Ladder (Fermentas), the lowest band is 250 bp (lane 3); positive control: cDNA amplified 84 bp fragment of β-actin gene (lane 4).

DISCUSSION

We describe a novel PGRN mutation causing a frameshift introducing a premature stop codon. RT-PCR analysis of PGRN mRNA levels confirmed the PGRN transcript decrease in the proband as compared to normal. Additionally, no amplification products of the mutant allele were detected suggesting that mRNA with the premature stop codon is rapidly degraded as a result of non-sense mediated decay [19]. There are no doubts about the pathological nature of this mutation. It segregates with the disease in two affected family members, it is absent in 200 normal controls, and immunohistochemistry confirms FTLD-U/TDP-43 pathology associated with mutant PGRN.

Patients affected with different PGRN mutations showed a broad range of age of onset (AOO; 48–83 years), with a mean of 59±7 years, often resulting in no family history recorded [8,20]. Another study also showed a highly variable AOO ranging from 49 to 88 years, with variable disease duration ranging from one to 14 years [12]. This novel PGRN deletion is associated with a rapid disease course and clear inheritance pattern. Consistent with other studies, AOO was variable with the proband’s brother developing symptoms seven years earlier.

The clinical course of FTD in the two siblings was different, particularly at illness onset (Table 1). The proband’s clinical features suggested early medial and dorsolateral prefrontal involvement with slowing, lack of motivation, and apathy. Shortly thereafter, social impairment and disinhibition were present, suggesting progression to orbitofrontal and right anterior temporal structures. Parkinsonism was also present. The behavioral disturbance correlated well with bifrontal and anterior temporal atrophy and hypoperfusion, worse on the right (Fig. 3). Language problems were observed later than behavioral impairment. The proband also had psychotic features including hallucinations, which is atypical in FTD.

In contrast, language disturbances came first in the proband’s brother. These were expressive with an early anomia progressing to a Broca’s aphasia and then to mutism. The initial symptoms of PNFA correlate with atrophy and hypoperfusion predominantly in the left frontal region (Fig. 1A–C). Later on, behavioral disturbance developed, which suggested progression to orbitofrontal and right anterior temporal regions, with social impropriety and disinhibition, culminating in apathy and cognitive decline. As the disease progressed from PNFA to include bvFTD so did the atrophy and perfusion deficits involving frontotemporal regions bilaterally (Fig. 2A–C). Apraxia was likely accounted for by the left frontoparietal involvement (Figs 1C and 2C) and these findings supported the third diagnosis of CBS. Visuospatial function was relatively preserved, correlating well with intact perfusion and absent pathology in the occipital regions, bilaterally.

The most common clinical presentation of PGRN mutation includes behavioral symptoms, with apathy as the dominant feature [21], similar to the proband. However, as is the case with his brother, clinical presentations of PNFA due to PGRN mutation are also frequent [22]. Several studies have confirmed this strong association between PNFA and PGRN mutations with the typical FTLD-U/TDP-43 pathology [21,23–25]. In particular, similar to the brother’s pathological findings, FTLD-U, type 3 pathology, was found to be most commonly associated with the clinical phenotype of PNFA [26]. In one series, semantic dementia cases were associated with MAPT mutations whereas PNFA with associated apraxia predicted PGRN mutations [24]. These particular case series were enriched with familial forms of FTD or were selected for based on a priori identification of PGRN mutation. Studies of predominantly sporadic cases of primary progressive aphasia selected for based on availability of pathological material demonstrated the opposite trend. Specifically, non-fluent presentations were associated with Tau pathology [27,28], while fluent cases were associated with ubiquitin pathology [28]. Longitudinal studies of familial and sporadic aphasic variants of FTD followed clinically until death with subsequent pathological characterization are warranted to clarify these apparent discrepant findings.

In the current study, both the proband and his brother developed parkinsonism. Indeed, FTD and parkinsonism due to PGRN mutation is common [29,30] and is more variable than that due to FTDP-17 with MAPT mutations [31]. In the former, there are often posterior features, such as limb apraxia and visuospatial dysfunction, which results in a wider clinical spectrum of diagnoses including dementia with Lewy bodies or CBS [31].

In general, the clinical heterogeneity and course of the affected siblings with this novel P439_R440fsX6 dinucleotide deletion resembles the course of other FTD patients with short-segment nucleotide PGRN deletions [11,25,32,33]. The particular type of mutation does not predict the clinical syndrome, but rather it is the location of the pathology which is most significant.

To date, significant progress has been made in understanding the allelic heterogeneity of PGRN mutation in FTD. This paper extends the literature on the allelic and phenotypic heterogeneity of FTD. However, progress in terms of understanding the variable clinical presentation of FTD, i.e., specific diagnoses, age of onset, hemispheric and specific lobar involvement and duration of disease remain to be explained. Studies examining polymorphism within PGRN miRNA binding sites and peripheral expression levels of PGRN may help to shed light on this phenotypic heterogeneity [34,35]. Using the approach of early identification of those at risk of developing FTD by imaging and CSF biomarkers coupled with a better understanding of genetic, epigenetic, and environmental modulators of disease will facilitate future development of preventative treatments and/or disease-modifying therapies for these devastating FTD syndromes.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Jaroslaw B. Cwikla from Dep. of Radiology and Diagnostic Imaging, Medical Centre for Postgraduate Education and CSK, MSWiA in Warsaw for comments and creating Fig. 1. The authors would also like to thank Mr. Mike Misch, Gregory Szilagyi, and Mark Gravely for creating Figs 1, 2, and 3 and Ms. Isabel Lam for creating Table 1. MM is supported by a Canadian Health Institutes of Research (CIHR) Clinician Scientist Award and the Department of Medicine, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre. This research is supported by operating grants from the CIHR (SEB, MT13129; PSGH and ER, MT417763) and the Ontario Research Fund (PSGH). ZW is supported by NIH/NINDS 1P50NS072187-01, 1RC2NS070276-01, 1R01NS057567-01A2; Carl Edward Bolch, Jr. and Susan Bass Bolch Gift, and Mayo Clinic Florida Research Committee. CZ and MB are supported by grant PBZ-MEiN-0/2/20/17.

Footnotes

Authors’ disclosures available online (http://www.jalz.com/disclosures/view.php?id=583).

References

- 1.Neary D, Snowden JS, Gustafson L, Passant U, Stuss D, Black S, Freedman M, Kertesz A, Robert PH, Albert M, Boone K, Miller BL, Cummings J, Benson DF. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: a consensus on clinical diagnostic criteria. Neurology. 1998;51:1546–1554. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.6.1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neumann M, Tolnay M, Mackenzie IR. The molecular basis of frontotemporal dementia. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2009;11:e23. doi: 10.1017/S1462399409001136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McKhann GM, Albert MS, Grossman M, Miller B, Dickson D, Trojanowski JQ. Clinical and pathological diagnosis of frontotemporal dementia: report of the Work Group on Frontotemporal Dementia and Pick’s Disease. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:1803–1809. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.11.1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Lund and Manchester Groups. Clinical and neuropathological criteria for frontotemporal dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1994;57:416–418. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.57.4.416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cairns NJ, Bigio EH, Mackenzie IR, Neumann M, Lee VM, Hatanpaa KJ, White CL, III, Schneider JA, Grinberg LT, Halliday G, Duyckaerts C, Lowe JS, Holm IE, Tolnay M, Okamoto K, Yokoo H, Murayama S, Woulfe J, Munoz DG, Dickson DW, Ince PG, Trojanowski JQ, Mann DM. Neuropathologic diagnostic and nosologic criteria for frontotemporal lobar degeneration: consensus of the Consortium for Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114:5–22. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0237-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baker M, Mackenzie IR, Pickering-Brown SM, Gass J, Rademakers R, Lindholm C, Snowden J, Adamson J, Sadovnick AD, Rollinson S, Cannon A, Dwosh E, Neary D, Melquist S, Richardson A, Dickson D, Berger Z, Eriksen J, Robinson T, Zehr C, Dickey CA, Crook R, McGowan E, Mann D, Boeve B, Feldman H, Hutton M. Mutations in progranulin cause tau-negative frontotemporal dementia linked to chromosome 17. Nature. 2006;442:916–919. doi: 10.1038/nature05016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cruts M, Gijselinck I, van der ZJ, Engelborghs S, Wils H, Pirici D, Rademakers R, Vandenberghe R, Dermaut B, Martin JJ, van DC, Peeters K, Sciot R, Santens P, De PT, Mattheijssens M, Van den BM, Cuijt I, Vennekens K, De Deyn PP, Kumar-Singh S, Van BC. Null mutations in progranulin cause ubiquitin-positive frontotemporal dementia linked to chromosome 17q21. Nature. 2006;442:920–924. doi: 10.1038/nature05017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gass J, Cannon A, Mackenzie IR, Boeve B, Baker M, Adamson J, Crook R, Melquist S, Kuntz K, Petersen R, Josephs K, Pickering-Brown SM, Graff-Radford N, Uitti R, Dickson D, Wszolek Z, Gonzalez J, Beach TG, Bigio E, Johnson N, Weintraub S, Mesulam M, White CL, III, Woodruff B, Caselli R, Hsiung GY, Feldman H, Knopman D, Hutton M, Rademakers R. Mutations in progranulin are a major cause of ubiquitin-positive frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:2988–3001. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahmed Z, Mackenzie IR, Hutton ML, Dickson DW. Progranulin in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and neuroinflammation. J Neuroinflammation. 2007;4:7. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-4-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neumann M, Sampathu DM, Kwong LK, Truax AC, Micsenyi MC, Chou TT, Bruce J, Schuck T, Grossman M, Clark CM, McCluskey LF, Miller BL, Masliah E, Mackenzie IR, Feldman H, Feiden W, Kretzschmar HA, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. Ubiquitinated TDP-43 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science. 2006;314:130–133. doi: 10.1126/science.1134108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benussi L, Binetti G, Sina E, Gigola L, Bettecken T, Meitinger T, Ghidoni R. A novel deletion in progranulin gene is associated with FTDP-17 and CBS. Neurobiol Aging. 2008;29:427–435. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kelley BJ, Haidar W, Boeve BF, Baker M, Graff-Radford NR, Krefft T, Frank AR, Jack CR, Jr, Shiung M, Knopman DS, Josephs KA, Parashos SA, Rademakers R, Hutton M, Pickering-Brown S, Adamson J, Kuntz KM, Dickson DW, Parisi JE, Smith GE, Ivnik RJ, Petersen RC. Prominent phenotypic variability associated with mutations in Progranulin. Neurobiol Aging. 2009;30:739–751. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Masellis M, Momeni P, Meschino W, Heffner R, Jr, Elder J, Sato C, Liang Y, St George-Hyslop P, Hardy J, Bilbao J, Black S, Rogaeva E. Novel splicing mutation in the progranulin gene causing familial corticobasal syndrome. Brain. 2006;129:3115–3123. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rademakers R, Baker M, Gass J, Adamson J, Huey ED, Momeni P, Spina S, Coppola G, Karydas AM, Stewart H, Johnson N, Hsiung GY, Kelley B, Kuntz K, Steinbart E, Wood EM, Yu CE, Josephs K, Sorenson E, Womack KB, Weintraub S, Pickering-Brown SM, Schofield PR, Brooks WS, Van DV, Snowden J, Clark CM, Kertesz A, Boylan K, Ghetti B, Neary D, Schellenberg GD, Beach TG, Mesulam M, Mann D, Grafman J, Mackenzie IR, Feldman H, Bird T, Petersen R, Knopman D, Boeve B, Geschwind DH, Miller B, Wszolek Z, Lippa C, Bigio EH, Dickson D, Graff-Radford N, Hutton M. Phenotypic variability associated with progranulin haploinsufficiency in patients with the common 1477C–>T (Arg493X) mutation: an international initiative. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:857–868. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70221-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rohrer JD, Beck J, Warren JD, King A, Al SS, Holton J, Revesz T, Collinge J, Mead S. Corticobasal syndrome associated with a novel 1048_1049insG progranulin mutation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80:1297–1298. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2008.169383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu CE, Bird TD, Bekris LM, Montine TJ, Leverenz JB, Steinbart E, Galloway NM, Feldman H, Woltjer R, Miller CA, Wood EM, Grossman M, McCluskey L, Clark CM, Neumann M, Danek A, Galasko DR, Arnold SE, Chen-Plotkin A, Karydas A, Miller BL, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM, Schellenberg GD, Van Deerlin V. The spectrum of mutations in progranulin: a collaborative study screening 545 cases of neurodegeneration. Arch Neurol. 2010;67:161–170. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zekanowski C, Styczynska M, Peplonska B, Gabryelewicz T, Religa D, Ilkowski J, Kijanowska-Haladyna B, Kotapka-Minc S, Mikkelsen S, Pfeffer A, Barczak A, Luczywek E, Wasiak B, Chodakowska-Zebrowska M, Gustaw K, Laczkowski J, Sobow T, Kuznicki J, Barcikowska M. Mutations in presenilin 1, presenilin 2 and amyloid precursor protein genes in patients with early-onset Alzheimer’s disease in Poland. Exp Neurol. 2003;184:991–996. doi: 10.1016/S0014-4886(03)00384-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zekanowski C, Peplonska B, Styczynska M, Gustaw K, Kuznicki J, Barcikowska M. Mutation screening of the MAPT and STH genes in Polish patients with clinically diagnosed frontotemporal dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2003;16:126–131. doi: 10.1159/000070999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baker KE, Parker R. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay: terminating erroneous gene expression. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2004;16:293–299. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brouwers N, Sleegers K, Engelborghs S, Maurer-Stroh S, Gijselinck I, van der ZJ, Pickut BA, Van den BM, Mattheijssens M, Peeters K, Schymkowitz J, Rousseau F, Martin JJ, Cruts M, De Deyn PP, Van BC. Genetic variability in progranulin contributes to risk for clinically diagnosed Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2008;71:656–664. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000319688.89790.7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beck J, Rohrer JD, Campbell T, Isaacs A, Morrison KE, Goodall EF, Warrington EK, Stevens J, Revesz T, Holton J, Al-Sarraj S, King A, Scahill R, Warren JD, Fox NC, Rossor MN, Collinge J, Mead S. A distinct clinical, neuropsychological and radiological phenotype is associated with progranulin gene mutations in a large UK series. Brain. 2008;131:706–720. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Snowden JS, Pickering-Brown SM, Mackenzie IR, Richardson AM, Varma A, Neary D, Mann DM. Progranulin gene mutations associated with frontotemporal dementia and progressive non-fluent aphasia. Brain. 2006;129:3091–3102. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moreno F, Indakoetxea B, Barandiaran M, Alzualde A, Gabilondo A, Estanga A, Ruiz J, Ruibal M, Bergareche A, Marti-Masso JF, Lopez de MA. “Frontotemporoparietal” dementia: clinical phenotype associated with the c.709-1G>A PGRN mutation. Neurology. 2009;73:1367–1374. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181bd82a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pickering-Brown SM, Rollinson S, Du PD, Morrison KE, Varma A, Richardson AM, Neary D, Snowden JS, Mann DM. Frequency and clinical characteristics of progranulin mutation carriers in the Manchester frontotemporal lobar degeneration cohort: comparison with patients with MAPT and no known mutations. Brain. 2008;131:721–731. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Skoglund L, Brundin R, Olofsson T, Kalimo H, Ingvast S, Blom ES, Giedraitis V, Ingelsson M, Lannfelt L, Basun H, Glaser A. Frontotemporal dementia in a large Swedish family is caused by a progranulin null mutation. Neurogenetics. 2009;10:27–34. doi: 10.1007/s10048-008-0155-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Snowden J, Neary D, Mann D. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: clinical and pathological relationships. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114:31–38. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0236-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Josephs KA, Petersen RC, Knopman DS, Boeve BF, Whitwell JL, Duffy JR, Parisi JE, Dickson DW. Clinicopathologic analysis of frontotemporal and corticobasal degenerations and PSP. Neurology. 2006;66:41–48. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000191307.69661.c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knibb JA, Xuereb JH, Patterson K, Hodges JR. Clinical and pathological characterization of progressive aphasia. Ann Neurol. 2006;59:156–165. doi: 10.1002/ana.20700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Josephs KA, Ahmed Z, Katsuse O, Parisi JF, Boeve BF, Knopman DS, Petersen RC, Davies P, Duara R, Graff-Radford NR, Uitti RJ, Rademakers R, Adamson J, Baker M, Hutton ML, Dickson DW. Neuropathologic features of frontotemporal lobar degeneration with ubiquitin-positive inclusions with progranulin gene (PGRN) mutations. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2007;66:142–151. doi: 10.1097/nen.0b013e31803020cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wong SH, Lecky BR, Steiger MJ. Parkinsonism and impulse control disorder: presentation of a new progranulin gene mutation. Mov Disord. 2009;24:618–619. doi: 10.1002/mds.22429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boeve BF, Hutton M. Refining frontotemporal dementia with parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17: introducing FTDP-17 (MAPT) and FTDP-17 (PGRN) Arch Neurol. 2008;65:460–464. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.4.460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Borroni B, Archetti S, Alberici A, Agosti C, Gennarelli M, Bigni B, Bonvicini C, Ferrari M, Bellelli G, Galimberti D, Scarpini E, Di LD, Caimi L, Caltagirone C, Di LM, Padovani A. Progranulin genetic variations in frontotemporal lobar degeneration: evidence for low mutation frequency in an Italian clinical series. Neurogenetics. 2008;9:197–205. doi: 10.1007/s10048-008-0127-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Llado A, Sanchez-Valle R, Rene R, Ezquerra M, Rey MJ, Tolosa E, Ferrer I, Molinuevo JL. Late-onset frontotemporal dementia associated with a novel PGRN mutation. J Neural Transm. 2007;114:1051–1054. doi: 10.1007/s00702-007-0716-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Finch N, Baker M, Crook R, Swanson K, Kuntz K, Surtees R, Bisceglio G, Rovelet-Lecrux A, Boeve B, Petersen RC, Dickson DW, Younkin SG, Deramecourt V, Crook J, Graff-Radford NR, Rademakers R. Plasma progranulin levels predict progranulin mutation status in frontotemporal dementia patients and asymptomatic family members. Brain. 2009;132:583–591. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rademakers R, Eriksen JL, Baker M, Robinson T, Ahmed Z, Lincoln SJ, Finch N, Rutherford NJ, Crook RJ, Josephs KA, Boeve BF, Knopman DS, Petersen RC, Parisi JE, Caselli RJ, Wszolek ZK, Uitti RJ, Feldman H, Hutton ML, Mackenzie IR, Graff-Radford NR, Dickson DW. Common variation in the miR-659 binding-site of GRN is a major risk factor for TDP43-positive frontotemporal dementia. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:3631–3642. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]