Abstract

The prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) worldwide has increased at an alarming rate, which will likely result in enormous medical and economic burden. NAFLD presents as a spectrum of liver diseases ranging from simple steatosis, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), fibrosis, cirrhosis, and even to hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). A comprehensive understanding of the mechanism(s) of NAFLD-to-NASH transition remains elusive with various genetic and environmental susceptibility factors possibly involved. An understanding of the mechanism may provide novel strategies in the prevention and treatment to NASH. Abnormal regulation of bile acid homeostasis emerges as an important mechanism to liver injury. The bile acid homeostasis is critically regulated by the farnesoid X receptor (FXR) that is activated by bile acids. FXR has been known to exert tissue-specific effects in regulating bile acid synthesis and transport. Current investigations demonstrate FXR also plays a principle role in regulating lipid metabolism and suppressing inflammation in the liver. Therefore, the future determination of the molecular mechanism by which FXR protects the liver from developing NAFLD may shed light to the prevention and treatment of NAFLD.

KEY WORDS: Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, Liver lipid metabolism, Bile acids, Farnesoid X receptor

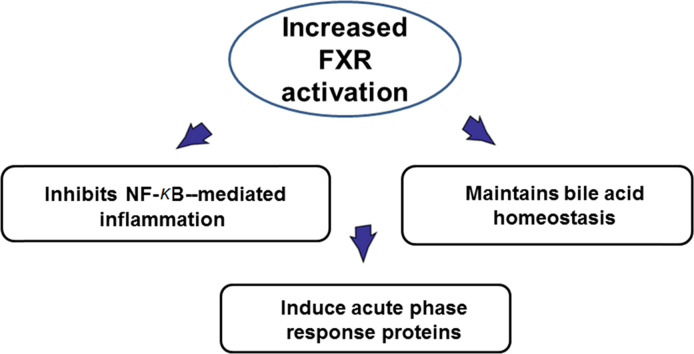

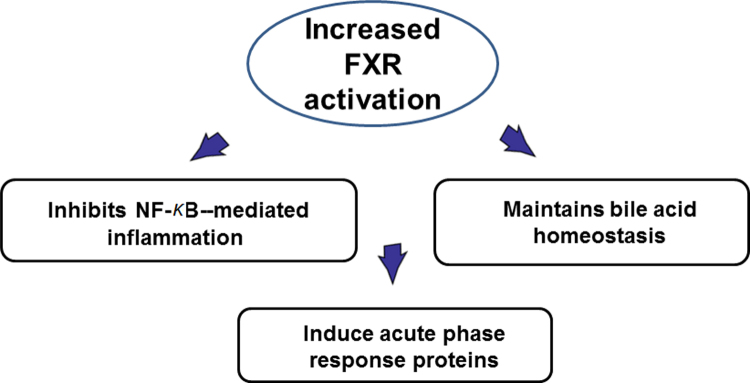

Graphical abstract

The prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) worldwide has increased at an alarming rate, which will likely result in enormous medical and economic burden. Farnesoid X receptor (FXR) was currcently confirmed to plays a principle role in regulating lipid metabolism and suppressing inflammation in the liver. FXR may exert its anti-inflammatory effects via (1) antagonizing NF-κB function, (2) maintaining bile acid homeostasis, and (3) inducing acute phase response proteins. These findings may shed light to the prevention and treatment of NAFLD.

1. Introduction to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), and liver lipid metabolism

The prevalence of NAFLD worldwide has increased at an alarming rate with 30%–40% estimated in developed countries, and this global liver disease will result in enormous medical and economic burden1. NAFLD presents as a spectrum of liver diseases initiated with excess accumulation of lipids in the hepatocytes in the absence of excess alcohol consumption. Although many NALFD cases are benign in prognosis, it is estimated that some cases will progress from simple steatosis to NASH, fibrosis, cirrhosis and even hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). NASH comprises dysregulation of lipid metabolism and increased inflammation, but a comprehensive understanding of the mechanism(s) of NAFLD-to-NASH transition remains elusive. Therefore, identification of the various genetic and environmental factors that contribute to the increased susceptibility to NASH may provide novel treatments to limit inflammation and fibrosis in NAFLD patients.

A considerable amount of efforts has been devoted to understand the mechanisms underlying simple steatosis-to-NASH transition. The most widely accepted theories are the “two-hit” and “multiple-hit” theories2, 3. A common proposal in both theories is the acknowledgments of the secondary factors related to lipid/cholesterol metabolism and inflammation that precipitate NASH in NAFLD patients are critical in the transition from simple steatosis to NASH.

2. Bile acids

Bile acids are synthesized from cholesterol in the liver and the enzymatic pathways have been well defined over the last 60 years4. There are two major pathways to synthesize bile acids—one is the classical or neutral pathway, initiated with the enzymatic reaction of cholesterol-7α-hydroxylase (CYP7A1), and the other one is the alternative or acidic pathway initiated by CYP27A1. The classical pathway produces cholic acid (CA) and the alternative pathway generates chenodeoxycholic acid (CDCA). In rodents and other species, CDCA is rapidly converted to more hydrophilic forms of bile acids in the liver, such as muricholic acid (MCA) or ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA). In addition to CYP7A1 and CYP27A1, there are at least two other pathways that lead to bile acid production involving cholesterol 24 and 25 hydroxylation. CA-, CDCA-, and UDCA-derived bile acids are termed primary bile acids that are conjugated in the liver to taurine or glycine. The conjugated bile acids are excreted into the bile, and, in the intestine, the intestinal microflora de-conjugate the primary bile acids and remove a hydroxylated group, generating secondary bile acids, deoxycholic acid (DCA) and lithocholic acid (LCA). Bile acids have been important during evolution and maybe undergone a variety of modifications5. Bile acids have been shown to not only serve as detergent in facilitating the intestinal absorption of lipids and lipid-soluble vitamins (vitamins A, D, K, and E), they are also critical in mediating cellular and molecular signals via activating nuclear receptors, FXR, pregnane X receptor, and vitamin D receptor, as well as G-protein coupled bile acid receptors, TGR5, and sphingosin-1-phosphate receptor 26. The revealed roles of bile acids in regulating liver functions, intestinal health, and systemic homeostasis are diverse.

3. FXR and tissue-specific roles of FXR in regulating bile acid homeostasis

The FXR gene (NR1H4/Nr1h4) was cloned in 19957 and in 1999, bile acids were identified as endogenous ligands of FXR with CDCA being the strongest endogenous ligand8, 9, 10. The generation of Fxr knockout (KO) mice has accelerated the research of the roles of FXR in physiology and pathology11. FXR deficiency in mice renders the animals to cholestasis11, disrupted cholesterol homeostasis12, susceptibility to atherosclerosis in a gender-dependent manner13, partial failure in liver regeneration14, 15, spontaneous HCC16, 17, increased NASH development18, and an elevated susceptibility to colon cancer formation19. Down-regulation of FXR expression and function has also been reported in human HCC and colon cancer20, 21. The underlying mechanisms by which FXR regulates these pathological processes appear to be due to either FXR-mediated, direct transcriptional regulation of critical mediators in the disease development, or via improving bile acid homeostasis, as increased bile acid levels have been shown to promote inflammation and tumorigenesis.

FXR exerts bile-acid regulatory effects via a tissue-specific mechanism. The activation of FXR in the liver and more critically, in the intestine, is critical in the feedback suppression of bile acid synthesis22, 23, 24, 25. In the intestine, activation of FXR induces the expression of an endocrine fibroblast growth factor 15 (FGF15, human homolog, FGF19), and the increased expression of FGF15 has been shown to mediate direct effects on suppressing bile acid synthesis and promote hepatic health23, 24, 26.

4. Tissue specific roles of FXR in regulating lipid metabolism and inflammation

The tissue specific effects of FXR have provided an interesting perspective to study liver-intestine axis24, 27. Clear tissue-specific roles of FXR have been proposed by genome-wide DNA ChIP-seq technology in mice28. It is very interesting to observe that there is only 11% overlap between FXR-binding sites between the liver and intestine, indicating underlying molecular mechanism of tissue-specific regulation by FXR activation. Furthermore, the annotated pathways in the liver and intestine predict differential functions of FXR in the liver and intestine. The detailed clarification of FXR functions in liver and intestine awaits further research. The human FXR genome-wide binding has been reported which supports the view that mice can be used as a model to study human FXR functions, particularly in diseases involved in lipid dysregulation and inflammation29. This is because the comparison between FXR genome-wide binding in mouse livers and in human primary hepatocytes reveals that FXR regulates a few conservative pathways in both species. FXR activation has been known to reduce triglyceride levels via suppressing de novo synthesis and uptake of fatty acids in the liver30, and recently, the roles of FXR in reducing inflammation have been emerging31. The FXR expression and function were reduced during acute phase response32. FXR activation strongly induced the expression of genes involved in anti-inflammation, such as kininogen33, facilitated the suppression of C-reactive protein production by interleukin 6 (IL-6)34, inhibited smooth muscle inflammation35, suppressed nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) activation in the liver36, reduced liver injury during systemic lupus erythematosus37, decreased inflammation induced by myofibroblasts38, induced acute phase proteins39, and decreased inflammation in the intestine40. In the liver, the molecular mechanism by which FXR antagonizes inflammation may be due to a acetyl/small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) switch so that SUMOylation of FXR increased FXR׳s ability to suppress NF-κB–mediated transcriptional induction of inflammatory genes41. But the role of FXR in inflammation has also been reported to be controversial42, perhaps reflecting the complexity of FXR in modulating inflammation and immune function under different diseases and/or different disease stages. The roles of FXR in the fight against liver inflammation have been summarized in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Proposed roles of hepatic FXR in anti-inflammation in the liver. FXR may exert its anti-inflammatory effects via (1) antagonizing NF-κB function; (2) maintaining bile acid homeostasis; and (3) inducing acute phase response proteins.

5. Future perspectives

Recently, a role of tissue-specific FXR functions in regulating fatty liver disease is emerging. It is reported that intestinal antagonism of FXR function inhibits sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c (SREBP-1c) function by reducing the production of ceramide in the intestine43, 44, indicating that intestinal inhibition/antagonism of FXR may present a promising opportunity in the treatment of liver steatosis. However, intestine-specific activation of FXR led to enhanced adipose tissue browning, which increased insulin sensitivity and reduced obesity45. These conflicting, interesting reports prompt further detailed studies of FXR's tissue specific effects on fatty liver formation, NASH development and metabolic syndrome progression. The recent development of FXR synthetic modulators in the treatment of NASH and cholestasis also urge us to careful define the functions of FXR in a tissue (cell)-specific, as well as species-dependent, manner.

Acknowledgments

This work is made possible by discussions with numerous colleagues, especially Drs. Bo Kong, Frank Gonzalez, Li Wang, Huiping Zhou, Curtis Klaassen and John Chiang. The work is also supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH, Nos. DK081343 and R01GM104037), as well as fund from the University of Kansas Medical Center and Rutgers University, USA.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Chinese Pharmaceutical Association.

References

- 1.Younossi Z.M., Koenig A.B., Abdelatif D., Fazel Y., Henry L., Wymer M. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease—meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence and outcomes. Hepatology. 2016;64:73–84. doi: 10.1002/hep.28431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Day C.P., James O.F. Steatohepatitis: a tale of two “hits”. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:842–845. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70599-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tilg H., Moschen A.R. Evolution of inflammation in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: the multiple parallel hits hypothesis. Hepatology. 2010;52:1836–1846. doi: 10.1002/hep.24001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Russell D.W. Fifty years of advances in bile acid synthesis and metabolism. J Lipid Res. 2009;50 Suppl:S120–S125. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800026-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hofmann A.F., Hagey L.R., Krasowski M.D. Bile salts of vertebrates: structural variation and possible evolutionary significance. J Lipid Res. 2010;51:226–246. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R000042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li G.D., Guo G.L. Farnesoid X receptor, the bile acid sensing nuclear receptor, in liver regeneration. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2015;5:93–98. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2015.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forman B.M., Goode E., Chen J., Oro A.E., Bradley D.J., Perlmann T. Identification of a nuclear receptor that is activated by farnesol metabolites. Cell. 1995;81:687–693. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90530-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Makishima M., Okamoto A.Y., Repa J.J., Tu H., Learned R.M., Luk A. Identification of a nuclear receptor for bile acids. Science. 1999;284:1362–1365. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parks D.J., Blanchard S.G., Bledsoe R.K., Chandra G., Consler T.G., Kliewer S.A. Bile acids: natural ligands for an orphan nuclear receptor. Science. 1999;284:1365–1368. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang H.B., Chen J., Hollister K., Sowers L.C., Forman B.M. Endogenous bile acids are ligands for the nuclear receptor FXR/BAR. Mol Cell. 1999;3:543–553. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80348-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sinal C.J., Tohkin M., Miyata M., Ward J.M., Lambert G., Gonzalez F.J. Targeted disruption of the nuclear receptor FXR/BAR impairs bile acid and lipid homeostasis. Cell. 2000;102:731–744. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00062-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lambert G., Amar M.J.A., Guo G., Brewer H.B., Jr, Gonzalez F.J., Sinal C.J. The farnesoid X-receptor is an essential regulator of cholesterol homeostasis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:2563–2570. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209525200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo G.L., Santamarina-Fojo S., Akiyama T.E., Amar M.J., Paigen B.J., Brewer B., Jr Effects of FXR in foam-cell formation and atherosclerosis development. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1761:1401–1409. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang W.D., Ma K., Zhang J., Qatanani M., Cuvillier J., Liu J. Nuclear receptor-dependent bile acid signaling is required for normal liver regeneration. Science. 2006;312:233–236. doi: 10.1126/science.1121435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borude P., Edwards G., Walesky C., Li F., Ma X.C., Kong B. Hepatocyte specific deletion of farnesoid X receptor delays, but does not inhibit liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy in mice. Hepatology. 2012;56:2344–2352. doi: 10.1002/hep.25918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim I., Morimura K., Shah Y., Yang Q., Ward J.M., Gonzalez F.J. Spontaneous hepatocarcinogenesis in farnesoid X receptor-null mice. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:940–946. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgl249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang F., Huang X.F., Yi T.S., Yen Y., Moore D.D., Huang W.D. Spontaneous development of liver tumors in the absence of the bile acid receptor farnesoid X receptor. Cancer Res. 2007;67:863–867. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kong B., Luyendyk J.P., Tawfik O., Guo G.L. Farnesoid X receptor deficiency induces nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in low-density lipoprotein receptor–knockout mice fed a high-fat diet. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;328:116–122. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.144600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maran R.R.M., Thomas A., Roth M., Sheng Z.H., Esterly N., Pinson D. Farnesoid X receptor deficiency in mice leads to increased intestinal epithelial cell proliferation and tumor development. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;328:469–477. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.145409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wolfe A., Thomas A., Edwards G., Jaseja R., Guo G.L., Apte U. Increased activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in spontaneous hepatocellular carcinoma observed in farnesoid X receptor knockout mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;338:12–21. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.179390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bailey A.M., Zhan L., Maru D., Shureiqi I., Pickering C.R. Kiriakova, et al. FXR silencing in human colon cancer by DNA methylation and KRAS signaling. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2014;306:G48–G58. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00234.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goodwin B., Jones S.A., Price R.R., Watson M.A., McKee D.D., Moore L.B. A regulatory cascade of the nuclear receptors FXR, SHP-1, and LRH-1 represses bile acid biosynthesis. Mol Cell. 2000;6:517–526. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00051-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inagaki T., Choi M., Moschetta A., Peng L., Cummins C.L., McDonald J.G. Fibroblast growth factor 15 functions as an enterohepatic signal to regulate bile acid homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2005;2:217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kong B., Wang L., Chiang J.Y., Zhang Y.C., Klaassen C.D., Guo G.L. Mechanism of tissue-specific farnesoid X receptor in suppressing the expression of genes in bile-acid synthesis in mice. Hepatology. 2012;56:1034–1043. doi: 10.1002/hep.25740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Song K.H., Li T.G., Owsley E., Strom S., Chiang J.Y. Bile acids activate fibroblast growth factor 19 signaling in human hepatocytes to inhibit cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase gene expression. Hepatology. 2009;49:297–305. doi: 10.1002/hep.22627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kong B., Huang J.S., Zhu Y., Li G.D., Williams J., Shen S. Fibroblast growth factor 15 deficiency impairs liver regeneration in mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2014;306:G893–G902. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00337.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim I., Ahn S.H., Inagaki T., Choi M., Ito S., Guo G.L. Differential regulation of bile acid homeostasis by the farnesoid X receptor in liver and intestine. J Lipid Res. 2007;48:2664–2672. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M700330-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thomas A.M., Hart S.N., Kong B., Fang J.W., Zhong X.B., Guo G.L. Genome-wide tissue-specific farnesoid X receptor binding in mouse liver and intestine. Hepatology. 2010;51:1410–1419. doi: 10.1002/hep.23450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhan L., Liu H.X., Fang Y.P., Kong B., He Y.Q., Zhong X.B. Genome-wide binding and transcriptome analysis of human farnesoid X receptor in primary human hepatocytes. PLoS One. 2014;9:e105930. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhu Y., Li F., Guo G.L. Tissue-specific function of farnesoid X receptor in liver and intestine. Pharmacol Res. 2011;63:259–265. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2010.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shaik F.B., Prasad D.V.R., Narala V.R. Role of farnesoid X receptor in inflammation and resolution. Inflamm Res. 2015;64:9–20. doi: 10.1007/s00011-014-0780-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim M.S., Shigenaga J., Moser A., Feingold K., Grunfeld C. Repression of farnesoid X receptor during the acute phase response. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:8988–8995. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212633200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhao A.N., Lew J.L., Huang L., Yu J.H., Zhang T., Hrywna Y. Human kininogen gene is transactivated by the farnesoid X receptor. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:28765–28770. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304568200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang S.W., Liu Q.Y., Wang J., Harnish D.C. Suppression of interleukin-6–induced C-reactive protein expression by FXR agonists. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;379:476–479. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.12.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li Y.T., Swales K.E., Thomas G.J., Warner T.D., Bishop-Bailey D. Farnesoid X receptor ligands inhibit vascular smooth muscle cell inflammation and migration. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:2606–2611. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.152694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang Y.D., Chen W.D., Wang M.H., Yu D., Forman B.M., Huang W.D. Farnesoid X receptor antagonizes nuclear factor κB in hepatic inflammatory response. Hepatology. 2008;48:1632–1643. doi: 10.1002/hep.22519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lian F., Wang Y., Chen J., Xu H.S., Yang X.Y., Liang L.Q. Activation of farnesoid X receptor attenuates liver injury in systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32:1705–1710. doi: 10.1007/s00296-011-1874-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Renga B., Mencarelli A., Migliorati M., Cipriani S., D׳Amore C., Distrutti E. SHP-dependent and -independent induction of peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor-γ by the bile acid sensor farnesoid X receptor counter-regulates the pro-inflammatory phenotype of liver myofibroblasts. Inflamm Res. 2011;60:577–587. doi: 10.1007/s00011-010-0306-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Porez G., Gross B., Prawitt J., Gheeraert C., Berrabah W., Alexandre J. The hepatic orosomucoid/α1-acid glycoprotein gene cluster is regulated by the nuclear bile acid receptor FXR. Endocrinology. 2013;154:3690–3701. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gadaleta R.M., van Erpecum K.J., Oldenburg B., Willemsen E.C.L., Renooij W., Murzilli S. Farnesoid X receptor activation inhibits inflammation and preserves the intestinal barrier in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2011;60:463–472. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.212159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim D.H., Xiao Z., Kwon S., Sun X.X., Ryerson D., Tkac D. A dysregulated acetyl/SUMO switch of FXR promotes hepatic inflammation in obesity. EMBO J. 2015;34:184–199. doi: 10.15252/embj.201489527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Capello A., Moons L.M., Van de Winkel A., Siersema P.D., van Dekken H., Kuipers E.J. Bile acid–stimulated expression of the farnesoid X receptor enhances the immune response in barrett esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1510–1516. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jiang C.T., Xie C., Li F., Zhang L.M., Nichols R.G., Krausz K.W. Intestinal farnesoid X receptor signaling promotes nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:386–402. doi: 10.1172/JCI76738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jiang C.T., Xie C., Lv Y., Li J., Krausz K.W., Shi J.M. Intestine-selective farnesoid X receptor inhibition improves obesity-related metabolic dysfunction. Nat Commun. 2015;6:10166. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fang S., Suh J.M., Reilly S.M., Yu E., Osborn O., Lackey D. Intestinal FXR agonism promotes adipose tissue browning and reduces obesity and insulin resistance. Nat Med. 2015;21:159–165. doi: 10.1038/nm.3760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]