Abstract

Background

Previous studies on high grade sarcomas using mass spectrometry imaging showed proteasome activator complex subunit 1 (PSME1) to be associated with poor survival in soft tissue sarcoma patients. PSME1 is involved in immunoproteasome assembly for generating tumor antigens presented by MHC class I molecules. In this study, we aimed to validate PSME1 as a prognostic biomarker in an independent and larger series of soft tissue sarcomas by immunohistochemistry.

Methods

Tissue microarrays containing leiomyosarcomas (n = 34), myxofibrosarcomas (n = 14), undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcomas (n = 15), undifferentiated spindle cell sarcomas (n = 4), pleomorphic liposarcomas (n = 4), pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcomas (n = 2), and uterine leiomyomas (n = 7) were analyzed for protein expression of PSME1 using immunohistochemistry. Survival times were compared between high and low expression groups using Kaplan–Meier analysis. Cox regression models as multivariate analysis were performed to evaluate whether the associations were independent of other important clinical covariates.

Results

PSME1 expression was variable among soft tissue sarcomas. In leiomyosarcomas, high expression was associated with overall poor survival (p = 0.034), decreased metastasis-free survival (p = 0.002) and lower event-free survival (p = 0.007). Using multivariate analysis, the association between PSME1 expression and metastasis-free survival was still significant (p = 0.025) and independent of the histological grade.

Conclusions

High expression of PSME1 is associated with poor metastasis-free survival in soft tissue leiomyosarcoma patients, and might be used as an independent prognostic biomarker.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13569-016-0057-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Proteasome activator complex subunit 1, Prognostic biomarker, Sarcoma, Leiomyosarcoma, Soft tissue sarcoma, Immunohistochemistry

Background

Soft tissue sarcomas are a heterogeneous group of rare malignancies often having poor outcome [1]. Soft tissue sarcomas constitute less than 1 % of all cancers [1] while there are more than 50 histological subtypes with sometimes overlapping histological features [2]. Distinction is essential as subtypes differ in biological behaviour and sensitivity to chemotherapy, and as such an adequate histological diagnosis, is crucial for clinical decision making [3]. Fifty-six percent of soft tissue sarcomas present as localized disease at the time of diagnosis, and surgery is the mainstay of treatment, sometimes combined with radiotherapy or chemotherapy [4].

From the molecular point of view, soft tissue sarcomas can be distinguished into two categories. The first class includes sarcomas with a simple genome, in which recurrent translocations, amplifications or specific mutations can be found. The second class includes sarcomas with a complex genome, characterized by a multitude of chromosomal alterations and genomic instability, often reflected by pleomorphic histological features [3]. This group includes high grade leiomyosarcoma, myxofibrosarcoma, undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma, undifferentiated spindle cell sarcoma, pleomorphic liposarcoma, and pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma.

Leiomyosarcomas constitute 5–10 % of all soft tissue sarcomas, displaying smooth-muscle differentiation [1]. Studies showed for leiomyosarcoma that the metastasis-free 5-year survival rate is about 60 % [5]. Histological grade is the most important prognostic factor for most soft tissue sarcomas. By using FNCLCC grading system, which is the most widely used 3-grade system, soft tissue sarcomas are divided into low, intermediate and high grade based on the sum score of three histologic parameters including tumor differentiation, mitotic count and tumor necrosis. About 65 % of leiomyosarcomas are reported to have high-grade areas [6]. High grade leiomyosarcomas often have poor patient outcome [4]. Until now, the genetics and pathology of leiomyosarcomas are not completely understood and as they have a complex genome, no molecular diagnostic tests or specific therapeutic targets are available. Hence, there is a strong need for new molecular markers that can aid in the stratification of leiomyosarcomas patients with respect to their disease outcome.

In a previous study, we used imaging mass spectrometry to compare these soft tissue sarcomas with a complex genome. A panel of protein signatures that could distinguish between different subtypes, or were associated to patient survival were discovered [7]. Among them, proteasome activator complex subunit 1 (PSME1) was found indicative of poor survival in soft tissue sarcomas. PSME1 (also known as REGalpha and PA28A), is a multicatalytic proteinase complex, implicated in immunoproteasome assembly and required for efficient antigen processing [8]. Intriguingly, PSME1 was also found to associate with diagnosis or prognosis in other tumor types, e.g. prostate cancer [9], breast cancer [10] and ovarian cancer [11, 12].

In this study, we used tissue microarrays of soft tissue sarcomas with complex genomes, to evaluate whether PSME1 expression can predict clinical outcome in soft tissue sarcomas, especially leiomyosarcomas.

Methods

Tissue microarrays

Tissue microarrays were previously constructed from paraffin embedded formalin fixed tissues using a semi-automated TMA apparatus (TMA Master; 3D Histech, Budapest, Hungary) [13]. Clinicopathological details were described previously [14]. In brief, analysed samples include 34 leiomyosarcomas, 14 myxofibrosarcomas, 15 undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcomas, four undifferentiated spindle cell sarcomas, four pleomorphic liposarcomas, two pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcomas, and seven uterine leiomyomas. Clinicopathological data for the leiomyosarcomas, as described previously [14], are summarized in Additional file 1: Table S1. All tumor samples are present at least in triplicates with a diameter of 1.5 mm (a surface area of around 1.767 mm2). Cores from colon, liver, placenta, prostate, skin, and tonsil were included for control and orientation purposes. Four micrometre thick sections were transferred by using a tape-transfer system to coated glass slides for analysis.

The histological diagnosis of all samples was confirmed by reviewing the hematoxylin and eosin—stained slides by expert pathologist (J. V. M. G. B.). Malignant tumors were graded according to the FNCLCC (French Fédération Nationale des Centres de Lutte Contre le Cancer) grading system [1]. All samples were handled according to the Dutch code of proper secondary use of human material as accorded by the Dutch society of pathology (Federa). The samples were handled in a coded manner. All study methods were approved by the LUMC ethical board (B16.025).

PSME1 immunohistochemistry

Four micrometre thick sections were dried overnight at 37 °C. Immunohistochemistry was performed using anti-PSME1 antibody (clone [EPR10968(B)], abcam, Cambridge, UK) according to protocols described previously [15]. Briefly, slides underwent deparaffinization, blocking of endogenous peroxidase, antigen retrieval (10 min microwave in citrate, pH 6.0), pre-incubation, and addition of the primary antibody in a dilution of 1:1500 overnight. Next, slides were incubated with Poly-HRP-GAM/R/R [Immunologic BV, Duiven, The Netherlands (DPVO110HRP)], visualized with DAB+Substrate Chromogen System (DAKO, Heverlee, Belgium) and counterstained with hematoxylin. Colon tissue was used as a positive control. As a negative control slides were incubated with PBS/1 % BSA instead of the primary antibody.

Scoring of immunohistochemistry

Slides were scored independently by two observers (J.V.M.G.B and A.H.G.C) as described previously [16]. In brief, staining intensity (0, absent; 1, weak; 2, moderate; 3, strong) and percentage of positive tumor cells (0, 0 %; 1, 1–24 %; 2, 25–49 %; 3, 50–74 %; 4, 75–100 %) were assessed. Afterwards, scores of staining intensity and percentage of positive tumor cells were added to obtain the sum score; for later statistical analysis, the average sum score was calculated over all cores belonging to the same tumor. Proteasomes are present both in the nucleus as well as in the cytoplasm of eukaryotic cells, although their relative abundance within these compartments can be highly variable [8, 17–20]. We therefore evaluated cytoplasmic and nuclear staining separately. Cores in which tissue was lost or with not enough tumor area were excluded from the analysis. Cores with differences on sum score from two observers more than two were re-evaluated to reach consensus.

Statistical analysis

Only primary tumour samples were used in statistical analysis. First, the distribution of sum score data was evaluated by Shapiro–Wilk normality test. As this test showed that the score data was not normally distributed, nonparametric Spearman correlation coefficient was used as a measure of the statistical dependence between the histological grades and PSME1 expression. Further statistical two-group comparisons between controls (uterine leiomyoma) and the different histological grades of soft tissue sarcomas were calculated by Dunn’s multiple-comparison test. Spearman correlation was performed in R environment (R Foundation for statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), scatter plots and Dunn’s test results were generated in GraphPad Prism version 6.00 for Windows (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, California, USA, http://www.graphpad.com). All two-sided p values equal or lower than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

For survival analysis, patients were dichotomized into two groups. We dichotomized leiomyosarcoma patients into high and low expression groups according to the sum scores of immunohistochemistry, for which we chose the cut-off at the 3rd quartile—Experience shows that molecular subgroups are usually found in 10–25 % of the patients (e.g. HER2 overexpression [21], KRAS mutation [22]). Differences in overall survival, metastasis-free survival and event-free survival between these groups were investigated using Kaplan–Meier curves and the log-rank test. Independent variables predicting survival were evaluated in a multivariable model using Cox Regression analyses. Survival analysis was performed in R environment (R Foundation for statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) using Survival package and all two-sided p values lower or equal than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Variable nuclear and cytoplasmic expression of PSME1 in soft tissue sarcomas

In soft tissue sarcomas, PSME1 protein expression was found in the majority of the cases, both in the nucleus as well as in the cytoplasm. In contrast, expression in benign leiomyoma was low or absent (Fig. 1a, b). Representative images of immunohistochemistry are shown in Fig. 2.

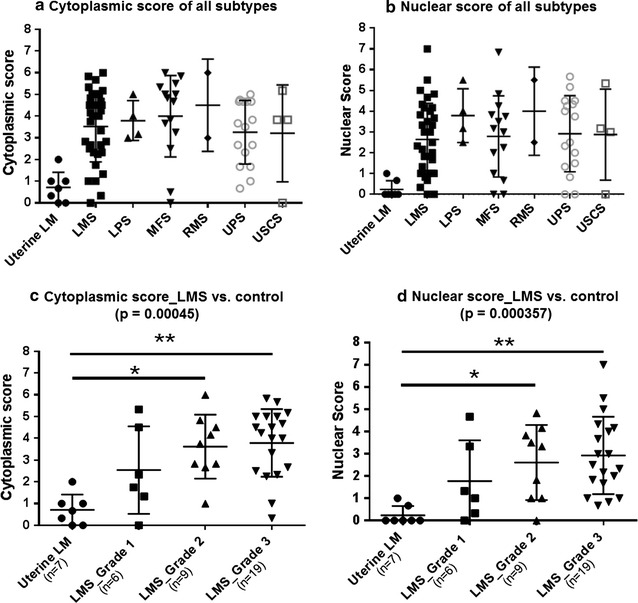

Fig. 1.

Summary of PSME1 immunohistochemistry results. Variable expression of PSME1 both in the cytoplasm (a) as well as in the nucleus (b) in soft tissue sarcomas, while expression in uterine leiomyoma (LM; control) is low. LMS leiomyosarcomas, LPS pleomorphic liposarcomas, MFS myxofibrosarcomas, RMS pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcomas, UPS undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcomas, and USCS undifferentiated spindle cell sarcomas. In leiomyosarcomas, both cytoplasmic (c) and nuclear (d) expression increased with increasing histological grade (p = 0.00045 and p = 0.000357). In addition, both cytoplasmic and nuclear expression of PSME1 was significantly higher in intermediate and high grade leiomyosarcomas as compared to uterine leiomyomas (p ≤ 0.05/p ≤ 0.01). All score data for each group were presented in mean ± SD

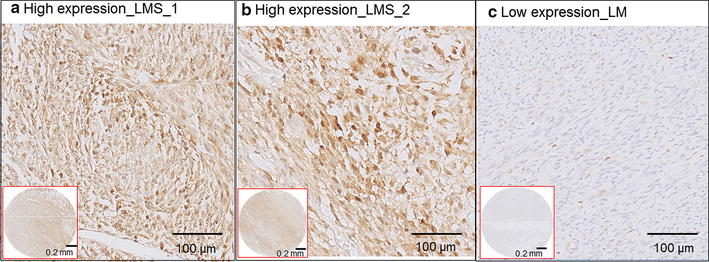

Fig. 2.

Representative images of immunohistochemistry of PSME1. a and b are two leiomyosarcoma (LMS) samples with high expression of PSME1. c A uterine leiomyoma (LM) control sample with low expression of PSME1. Images in red squares are the overviews of expression the tissue microarray cores for respective samples

Increased expression of PSME1 with increasing histological grade in leiomyosarcomas

The leiomyosarcoma subgroup was large enough to analyse a possible correlation with histological grade. Indeed, while expression was low to absent in uterine leiomyoma, expression gradually increased with increasing histological grade in both nucleus (poverall = 0.000357) and cytoplasm (poverall = 0.00045) in leiomyosarcomas (Fig. 1c, d). Further statistical two groups comparisons between control and any histological grade by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test showed that both nuclear and cytoplasmic staining significantly differed in uterine leiomyomas versus leiomyosarcomas grade 2 (p ≤ 0.05) and uterine leiomyomas versus leiomyosarcomas grade 3 (p ≤ 0.01).

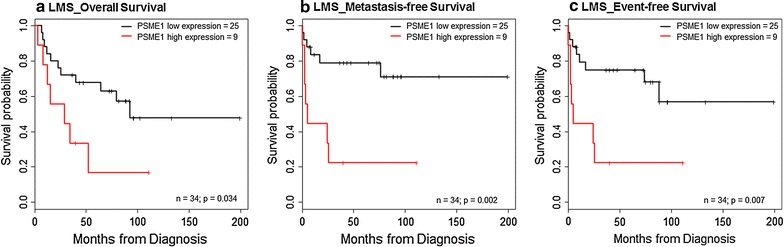

High nuclear expression of PSME1 predicts poor outcome in leiomyosarcoma patients

To investigate a possible correlation of PSME1 expression with clinical outcome, leiomyosarcoma patients were dichotomized into high and low PSME1 expression groups according to the sum scores of immunohistochemistry. High PSME1 expression was associated with poor overall survival (p = 0.034), decreased metastasis-free survival (p = 0.002) and lower event-free survival (p = 0.007) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Kaplan–Meier survival plots of PSME1. Kaplan–Meier plots comparing the different survival data of leiomyosarcoma patients with respect to a high and low nuclear expression of PSME1 (cut-off: 3rd quartile). High nuclear expression of PSME1 in leiomyosarcoma was significantly associated with decreased overall survival, metastasis-free survival and event-free survival (log-rank test; p ≤ 0.05)

High nuclear expression of PSME1 as an independent prognostic factor in leiomyosarcoma patients

Using multivariable Cox Regression analyses including clinically relevant co-factors such as histological grade, age and gender, we showed that high nuclear expression of PSME1 was independently associated with metastasis-free survival (p = 0.03) (Table 1). The independent predictive power of nuclear PSME1 expression for overall and event-free survival was at the border of significance (p = 0.07) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Results of multivariable analysis of factors influencing survival

| Clinical association | Variable | Hazards ratio | 95 % Confidence interval | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metastasis-free survival | ||||

| PSME1 high nuclear expression | 3.685 | 1.177–11.541 | 0.025* | |

| Histological grade | 1.831 | 0.710–4.723 | 0.211 | |

| Age | 0.974 | 0.932–1.017 | 0.225 | |

| Gender (M) | 0.377 | 0.070–2.039 | 0.257 | |

| Event-free survival | ||||

| PSME1 high nuclear expression | 2.667 | 0.919–7.743 | 0.071 | |

| Histological grade | 2.216 | 0.882–5.569 | 0.090 | |

| Age | 0.975 | 0.937–1.015 | 0.215 | |

| Gender (M) | 0.339 | 0.068–1.695 | 0.188 | |

| Overall survival | ||||

| PSME1 high nuclear expression | 2.612 | 0.916–7.448 | 0.072 | |

| Histological grade | 2.552 | 0.953–6.837 | 0.062 | |

| Age | 1.005 | 0.972–1.039 | 0.758 | |

| Gender (M) | 2.071 | 0.660–6.502 | 0.212 | |

* p value reaches statistically significant level (p ≤ 0.05)

Discussion

Using imaging mass spectrometry we previously identified PSME1 as a prognostic biomarker indicating poor survival in soft tissue sarcoma patients [7]. Imaging mass spectrometry is a sensitive discovery tool (zepto-molar sensitivity [23]) enabling the detection of hundreds of molecules directly from tissue [24, 25]. To further explore the prognostic value of PSME1 we analysed PSME1 expression in a larger, independent set of soft tissue sarcomas using immunohistochemistry on tissue microarrays. PSME1 (or PA28A) encodes a subunit of the proteasome system, which is a major source for generation of tumor antigens presented by MHC class I molecules [26, 27]. Escape of immune response is one of the hallmarks of cancer [28]. In addition, elevated proteasome activity in tumor cells has been described to influence transcription factors involved in cell survival or apoptosis [29, 30]. Novel strategies using the proteasome have been proposed for cancer treatment for example by alternating the NAD+/NADH ratio to change kinetics of proteasomal degradation [30] or inhibiting proteasome to induce apoptosis [31–34].

PSME1 is expressed in many different cell types, especially antigen presenting cells, and its expression can be controlled by interferon gamma. Both chemotherapy and TNF-alpha may induce a local inflammatory reaction within the tumor microenvironment and therefore may influence expression of PSME1. It is of interest that all sarcoma subtypes included in our study expressed PSME1 to a variable extent, while neoadjuvant chemotherapy or treatment with interferon gamma is not standard practice in our hospital. As far as clinical data were available, only four patients received preoperative chemotherapy or TNF-alpha, and expression levels were not significantly different. In the control group, consisting of uterine leiomyomas, expression was low to absent, both in the nucleus as well as in the cytoplasm.

High PSME1 expression was also described in other tumors. For example, increased PSME1 expression was also found in primary and metastatic human prostate cancer and was suggested as a potential target for therapeutic intervention [9]. PSME1 was previously also detected using imaging mass spectrometry in other tumors: Dekker et al. detected PSME1 as a marker of stromal activation in breast cancer [10]. Previous studies also showed that PSME1 could be a molecular signature to discriminate between benign and malignant ovarian tumors [11, 35], and an early diagnosis and tumor-relapse biomarker [12]. Zhang et al. detected PSME1 as a tumor marker in human oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma [36]. The proteasome can be present in the cytoplasm as well as in the nucleus of all eukaryotic cells, although their distribution and function can be variable [17]. We here show that in soft tissue sarcomas with a complex genome, PSME1 is expressed both in the cytoplasm and in the nucleus. Proteasome-dependent protein degradation is important in the cytoplasm for MHC class 1 antigen presentation [8]. In the nucleus, PSME1 plays an important role in maintaining the nuclear function including gene expression and cell proliferation [19, 37].

To further evaluate its clinical relevance, we analysed the largest subgroup, comprising 34 leiomyosarcomas of different histological grade, in more detail. Both nuclear as well as cytoplasmic expression of PSME1 significantly increased with increasing histological grade. Moreover, high nuclear expression of PSME1 was significantly associated to poor outcome (overall survival, metastasis-free survival and event-free survival) in leiomyosarcoma patients, although the patient cohort is rather small (n = 34). In multivariate analysis only the association with decreased metastasis-free survival was independent of histological grade, while an independent association to poor overall survival and decreased event-free survival was at the border of significance. Although PMSE1 expression is a promising biomarker, our results need to be validated in an independent cohort of leiomyosarcomas.

In summary, we found elevated expression of the proteasome subunit PSME1 in leiomyosarcomas compared to control tissues, and an association of the expression with increasing histological grade in leiomyosarcoma. Moreover, high nuclear PSME1 expression was found to be an independent predictor of metastasis-free survival in leiomyosarcoma patients. Our results suggest that the expression of proteasome subunits such as PSME1 could be taken into account for leiomyosarcoma patients when considering immunotherapeutic strategies in these tumors [38].

Conclusions

We show variable expression of PSME1 in different soft tissue sarcoma subtypes with complex genomes. Our results showed that high nuclear expression of proteasome activator complex subunit 1 is an independent poor prognostic factor in leiomyosarcomas, which suggests that the proteasome could be exploited as a possible novel target for the treatment of leiomyosarcomas.

Authors’ contributions

SL: data analysis and interpretation, writing of manuscript. AHGC: immunohistochemistry scoring, data interpretation. BB: statistical analysis. MG: tissue microarrays’ construction. MK: data collection and analysis. IBB: experimental work. LAM: design and supervision of the study. JVMGB: immunohistochemistry scoring, design and supervision of the study, writing of manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank B.E.W.M. van den Akker for technical assistance.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and supporting materials

The manuscript and the supplementary files contain all potential findings based on raw data analysis. Raw data can be obtained from authors on request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All samples were handled according to the Dutch code of proper secondary use of human material as accorded by the Dutch society of pathology (Federa). The samples were handled in a coded manner. All study methods were approved by the LUMC ethical board (B16.025).

Funding

The authors would like to acknowledge financial support from COMMIT, Cyttron II and the ZonMW Zenith project Imaging Mass Spectrometry-Based Molecular Histology: Differentiation and Characterization of Clinically Challenging Soft Tissue Sarcomas (No. 93512002). BB is funded by the Marie Curie Action of the European Union (SITH FP7-PEOPLE-2012-IEF No. 331866).

Abbreviations

- PSME1

proteasome activator complex subunit one

- LMS

leiomyosarcomas

- MFS

myxofibrosarcomas

- UPS

undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcomas

- Uterine LM

uterine leiomyomas

- LPS

pleomorphic liposarcomas

- RMS

pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcomas

- USCS

undifferentiated spindle cell sarcomas

Additional file

10.1186/s13569-016-0057-z Clinicopathologic characterization of leiomyosarcoma patients [14].

Contributor Information

Sha Lou, Email: s.lou@lumc.nl, Email: lousha0611@gmail.com.

Arjen H. G. Cleven, Email: A.H.G.Cleven@lumc.nl

Benjamin Balluff, Email: b.balluff@maastrichtuniversity.nl.

Marieke de Graaff, Email: M.A.de_Graaff.PATH@lumc.nl.

Marie Kostine, Email: M.Kostine@lumc.nl.

Inge Briaire-de Bruijn, Email: I.H.Briaire-de_Bruijn@lumc.nl.

Liam A. McDonnell, Email: l.a.mcdonnell@outlook.com

Judith V. M. G. Bovée, Phone: +31 71 526 6617, Email: J.V.M.G.Bovee@lumc.nl

References

- 1.Fletcher CDM, Bridge JA, Hogendoorn PCW, Mertens F. WHO classification of tumors of soft tissue and bone. 4. Lyon: WHO Press; 2013. pp. 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taylor B, Barretina J, Maki R, Antonescu C, Singer S, Ladanyi M. Advances in sarcoma genomics and new therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:541–557. doi: 10.1038/nrc3087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jain S, Xu R, Prieto VG, Lee P. Molecular classification of soft tissue sarcomas and its clinical applications. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2010;3:416–428. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arifi S, Belbaraka R, Rahhali R, Ismaili N. Treatment of adult soft tissue sarcomas: an overview. Rare Cancers Ther. 2015;3:69–87. doi: 10.1007/s40487-015-0011-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coindre JM, Terrier P, Guillou L, Le Doussal V, Collin F, Ranchère D, et al. Predictive value of grade for metastasis development in the main histologic types of adult soft tissue sarcomas: a study of 1240 patients from the French Federation of Cancer Centers Sarcoma Group. Cancer. 2001;91:1914–1926. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010515)91:10<1914::AID-CNCR1214>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pisters PW, Leung DH, Woodruff J, Shi W, Brennan MF. Analysis of prognostic factors in 1041 patients with localized soft tissue sarcomas of the extremities. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:1679–1689. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.5.1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lou S, Balluff B, de Graaff MA, Cleven AH, Briaire-de Bruijn IH, Bovée JV, et al. High grade sarcoma diagnosis and prognosis: biomarker discovery by mass spectrometry imaging. Proteomics. 2016;16:1802–1813. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201500514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vigneron N, van den Eynde BJ. Proteasome subtypes and regulators in the processing of antigenic peptides presented by class I molecules of the major histocompatibility complex. Biomolecules. 2014;4:994–1025. doi: 10.3390/biom4040994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sanchez-Martin D, Martinez-Torrecuadrada J, Teesalu T, Sugahara KN, Alvarez-Cienfuegos A, Ximenez-Embun P, et al. Proteasome activator complex PA28 identified as an accessible target in prostate cancer by in vivo selection of human antibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:13791–13796. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1300013110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dekker TJ, Balluff BD, Jones EA, Schone CD, Schmitt M, Aubele M, et al. Multicenter matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry imaging (MALDI MSI) identifies proteomic differences in breast-cancer-associated stroma. J Proteome Res. 2014;13:4730–4738. doi: 10.1021/pr500253j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lemaire R, Menguellet SA, Stauber J, Marchaudon V, Lucot JP, Collinet P, et al. Specific MALDI imaging and profiling for biomarker hunting and validation: fragment of the 11S proteasome activator complex, Reg alpha fragment, is a new potential ovary cancer biomarker. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:4127–4134. doi: 10.1021/pr0702722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Longuespee R, Boyon C, Castellier C, Jacquet A, Desmons A, Kerdraon O, et al. The C-terminal fragment of the immunoproteasome PA28S (Reg alpha) as an early diagnosis and tumor-relapse biomarker: evidence from mass spectrometry profiling. Histochem Cell Biol. 2012;138:141–154. doi: 10.1007/s00418-012-0953-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Graaff MA, Cleton-Jansen AM, Szuhai K, Bovée JV. Mediator complex subunit 12 exon 2 mutation analysis in different subtypes of smooth muscle tumors confirms genetic heterogeneity. Hum Pathol. 2013;44:1597–1604. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2013.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Graaff MA, de Rooij MA, van den Akker BE, Gelderblom H, Chibon F, Coindre JM, et al. Inhibition of Bcl-2 family members sensitises soft tissue leiomyosarcomas to chemotherapy. Br J Cancer. 2016;24:1219–1226. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2016.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baranski Z, Booij TH, Cleton-Jansen AM, Price LS, van de Water B, Bovée JV, et al. Aven-mediated checkpoint kinase control regulates proliferation and resistance to chemotherapy in conventional osteosarcoma. J Pathol. 2015;236:348–359. doi: 10.1002/path.4528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoekstra AS, de Graaff MA, Briaire-de Bruijn IH, Ras C, Seifar RM, van Minderhout I, et al. Inactivation of SDH and FH cause loss of 5hmC and increased H3K9me3 in paraganglioma/pheochromocytoma and smooth muscle tumors. Oncotarget. 2015;6:38777–38788. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wójcik C, DeMartino GN. Intracellular localization of proteasomes. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2003;35:579–589. doi: 10.1016/S1357-2725(02)00380-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Groettrup M, Soza A, Eggers M, Kuehn L, Dick TP, Schild H, et al. A role for the proteasome regulator PA28alpha in antigen presentation. Nature. 1996;381:166–168. doi: 10.1038/381166a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.von Mikecz A. The nuclear ubiquitin-proteasome system. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:1977–1984. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muratani M, Tansey WP. How the ubiquitin-proteasome system controls transcription. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:192–201. doi: 10.1038/nrm1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hetzel DJ, Wilson TO, Keeney GL, Roche PC, Cha SS, Podratz KC. HER-2/neu expression: a major prognostic factor in endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 1992;47:179–185. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(92)90103-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ohtaki Y, Shimizu K, Kakegawa S, Nagashima T, Nakano T, Atsumi J, et al. Postrecurrence survival of surgically resected pulmonary adenocarcinoma patients according to EGFR and KRAS mutation status. Mol Clin Oncol. 2014;2:187–196. doi: 10.3892/mco.2013.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jungmann J, Heeren R. Emerging technologies in mass spectrometry imaging. J Proteom. 2012;75:5077–5092. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2012.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McDonnell LA, Heeren RM. Imaging mass spectrometry. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2007;26:606–643. doi: 10.1002/mas.20124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McDonnell LA, Corthals GL, Willems SM, van Remoortere A, van Zeijl RJ, Deelder AM. Peptide and protein imaging mass spectrometry in cancer research. J Proteom. 2010;73:1921–1944. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sijts A, Sun Y, Janek K, Kral S, Paschen A, Schadendorf D, et al. The role of the proteasome activator PA28 in MHC class I antigen processing. Mol Immunol. 2002;39:165–169. doi: 10.1016/S0161-5890(02)00099-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hochstrasser M. Ubiquitin-dependent protein degradation. Annu Rev Genet. 1996;30:405–439. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.30.1.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu Q, Wani G, Yao J, Patnaik S, Wang QE, El-Mahdy MA, et al. The ubiquitin–proteasome system regulates p53-mediated transcription at p21waf1 promoter. Oncogene. 2007;26:4199–4208. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsvetkov P, Reuven N, Shaul Y. Ubiquitin-independent p53 proteasomal degradation. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17:103–108. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Almond JB, Cohen GM. The proteasome: a novel target for cancer chemotherapy. Leukemia. 2002;16:433–443. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Montagut C, Rovira A, Albanell J. The proteasome: a novel target for anticancer therapy. Clin Transl Oncol. 2006;8:313–317. doi: 10.1007/s12094-006-0176-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Voorhees PM, Orlowski RZ. The proteasome and proteasome inhibitors in cancer therapy. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2006;46:189–213. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.46.120604.141300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Orlowski R, Dees EC. The role of the ubiquitination-proteasome pathway in breast cancer: applying drugs that affect the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway to the therapy of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2003;5:1–7. doi: 10.1186/bcr460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.El Ayed M, Bonnel D, Longuespée R, Castelier C, Franck J, Vergara D, et al. MALDI imaging mass spectrometry in ovarian cancer for tracking, identifying, and validating biomarkers. Med Sci Monit. 2010;16(8):BR233–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang J, Wang K, Zhang J, Liu SS, Dai L, Zhang JY. Using proteomic approach to identify tumor-associated proteins as biomarkers in human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Proteome Res. 2011;10:2863–2872. doi: 10.1021/pr200141c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.von Mikecz A, Chen M, Rockel T, Scharf A. The nuclear ubiquitin-proteasome system: visualization of proteasomes, protein aggregates, and proteolysis in the cell nucleus. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;463:191–202. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-406-3_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lim J, Poulin NM, Nielsen TO. New strategies in sarcoma: linking genomic and immunotherapy approaches to molecular subtype. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:4753–4759. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]