Abstract

Raghavan et al. (2008) proposed that effective implementation of evidence-based practices requires implementation strategies deployed at multiple levels of the “policy ecology,” including the organizational, regulatory or purchaser agency, political, and social levels. However, much of implementation research and practice targets providers without accounting for contextual factors that may influence provider behavior. This paper examines Philadelphia’s efforts to work toward an evidence-based and recovery-oriented behavioral health system, and uses the policy ecology framework to illustrate how multifaceted, multilevel implementation strategies can facilitate the widespread implementation of evidence-based practices. Ongoing challenges and implications for research and practice are discussed.

Keywords: Behavioral Health Systems, Implementation Strategies, Policy, Evidence-Based Practices

Introduction

The last fifteen years have seen a growing interest in the implementation of evidence-based practices (EBPs) by publicly-funded community mental health clinics, largely in response to policy mandates (Ganju, 2003). Many of these efforts have focused on clinician-level implementation strategies (Novins, Green, Legha, & Aarons, 2013; Powell, Proctor, & Glass, 2014; Raghavan et al., 2008) despite the fact that both the conceptual (Aarons, Hurlburt, & Horwitz, 2011; Damschroder et al., 2009; Tabak, Khoong, Chambers, & Brownson, 2012) and empirical literature (Hoagwood et al., 2014; Isett et al., 2007; Magnabosco, 2006) suggest the importance of contextual determinants of provider and organizational behavior (e.g., organizational culture and climate, funding, policy context). Raghavan et al. (2008) suggest that ignoring the broader “policy ecology” of implementation is ill advised, and propose a useful heuristic for understanding the breadth of multi-level strategies required to implement EBPs. We apply this framework to an ongoing system transformation effort in Philadelphia to demonstrate how the policy ecology framework can be operationalized within a system as a case study to inform policymakers, administrators, and implementation researchers attempting to implement EBPs in large public behavioral health systems. We begin by describing the policy ecology framework and the context of Philadelphia’s behavioral health system and its transformation efforts. We then detail some of the strategies that have been used at various levels of the policy ecology to accomplish the system’s goals. We then conclude by discussing implications for system-level implementation research and practice.

The Policy Ecology Framework

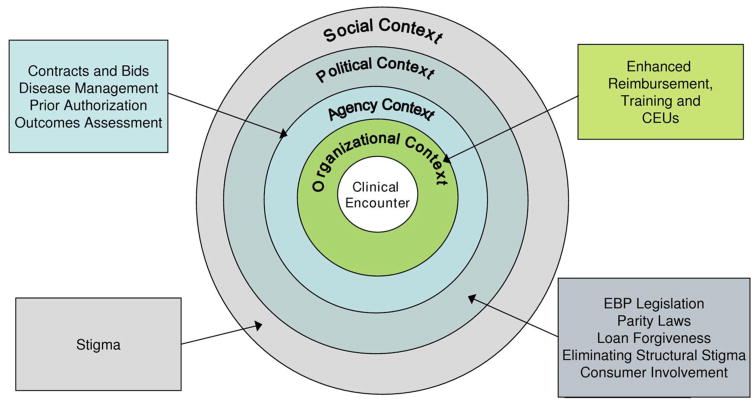

The “policy ecology” as described by Raghavan et al. (2008) consists of four levels that comprise the broader context of EBP implementation: organizational context, regulatory or purchaser agency, political, and social (see Figure 1). The organizational level is most proximal to the actual delivery of EBPs, as it forms the immediate context within which clinicians deliver behavioral health services. Organizational contexts can vary in size and complexity, ranging from small group practices to large, multidisciplinary mental health facilities. The regulatory or purchaser agency level includes state and city departments of behavioral health and the broader regulatory and funding environment that provides the immediate context for organizations delivering mental health care. The political level is defined as the legislative and advocacy efforts that enable EBP implementation. Finally, the social level includes the “societal norms and subcultures that affect consumers’ access to EBPs” (Raghavan et al., 2008, p. 3). These levels are not mutually exclusive; many determinants of practice (i.e., barriers and facilitators) and implementation strategies will span multiple levels. However, the distinct levels provide a useful organizing framework that can facilitate a better understanding of what it takes to implement EBPs well, and Raghavan et al. (2008) emphasize how policy makers and implementation researchers can effect change at each of the levels.

Figure 1.

The policy ecology framework as depicted by Raghavan et al. (2008)

Numerous implementation frameworks emphasize factors at the “inner” (i.e., organizational) and “outer” (i.e., regulatory and funding, political, and social) levels, including the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (Damschroder et al., 2009) and the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, and Sustainment Model (Aarons et al., 2011), the latter of which has a clear focus on inner and outer settings within public sectors of care. However, the policy ecology framework (Raghavan et al., 2008) was chosen for two reasons. First, we believe the policy ecology framework most clearly articulates the challenges and strategies associated with those “inner” and “outer” setting levels in public behavioral health, and that it extends the value of alternative frameworks by including factors at the social level, such as stigma and public health strategies that influence the implementation of EBPs. This makes it a particularly good fit for framing Philadelphia’s efforts to promote recovery, which have included specific implementation strategies designed to integrate EBPs into community settings as well as broader public health approaches intended to reduce stigma and enhance access to behavioral health services. Second, we believe that the policy ecology offers a useful metaphor that is superior to alternatives (e.g., “environment”) in describing the complexity of implementing EBPs in Philadelphia. The metaphor of “environment,” for example, conjures up images of something “out there,” something separate, a force or set of forces to be reckoned with, but something more like the weather, something that affects implementation but is separate from it. Conversely, the metaphor of “ecology” emphasizes that the actors and elements within a system are interactive and interdependent (Weiner, 2015), leading Raghavan et al. (2008) to implore policymakers to “align the effects of policy action across all of these contexts in order to produce ‘sustained, system-wide uptake’ of EBPs” (p. 3).

In many ways, the policy ecology framework provides systems that wish to implement evidence-based care something to aspire to by highlighting a range of potential strategies that could provide broad support for EBPs. However, in the Raghavan et al. (2008) article, the examples of potential implementation strategies were drawn from a variety of sources, some real and some hypothetical. We believe Philadelphia’s behavioral health transformation efforts provide an apt case example of how policymakers can work to carefully align strategies to address barriers and facilitators at the various levels of the often-neglected policy ecology. By detailing Philadelphia’s efforts to support the implementation and sustainment of EBPs, we contribute to the literature by fleshing out the policy ecology framework and demonstrating how it could be used to frame the conceptualization, planning, or evaluation of large-scale change efforts.

Philadelphia’s Behavioral Health Transformation Effort

Philadelphia’s Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual disAbility Services (DBHIDS) is the primary funder and policymaker for behavioral health services in the City of Philadelphia. In partnership with Community Behavioral Health, a not-for-profit 501(c)(3) corporation contracted by the City of Philadelphia, they provide behavioral health coverage for the City’s over 500,000 Medicaid-enrolled individuals (Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual disAbility Services, 2015a). They are well positioned to address each level of the policy ecology to insure the effective implementation of EBPs. Over the past decade, DBHIDS has undertaken a system-wide transformation to ensure that services are based upon the principles of recovery, resilience, and self-determination to achieve the best outcomes (Abrahams et al., 2013). The Commissioner of DBHIDS, Dr. Arthur Evans, recognized that helping people to recover would require leveraging the best science, and that EBPs are foundational priority for recovery-oriented behavioral health service provision (Williams et al., 2016). Thus, an important part of the transformation effort is a commitment to “…align resources, policies and technical assistance to support the ongoing transformation of our system to one that promotes and routinely utilizes evidence-based practices” (Abrahams et al., 2013, p. A–7).1 Thus, DBHIDS has partnered closely with treatment developers and community organizations to increase the system’s capacity to deliver EBPs. The first partnership to implement EBPs more widely in Philadelphia was initiated by Dr. Aaron T. Beck. Dr. Beck contacted Dr. Evans because despite years of research demonstrating the effectiveness of cognitive therapy, it was still not widely implemented, particularly in public behavioral health settings. Dr. Evans’ background in experimental, clinical, and community psychology sensitized him to opportunities to integrate science into practice, and made him eager to invest in partnerships to implement EBPs more widely. He remains committed to EBPs not only because of their scientific backing, but because he believes that they are utilitarian and address concrete needs within the public behavioral health system. Dr. Evans’ steadfast commitment and vision for transformation, coupled with his willingness to partner with a wide range of stakeholders (e.g., community members, treatment developers, academics, etc.) have been essential to maintaining the momentum and continuity of the City’s large-scale implementation efforts. It was also fortuitous that Dr. Beck and a host of other treatment developers were located in and around the Philadelphia area, though at this point, DBHIDS has developed relationships with non-local treatment developers and purveyors as well. To date, four major initiatives have been launched: 1) the Beck Initiative, launched in 2007 to implement cognitive therapy; 2) the Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Initiative, launched in 2011; 3) the Prolonged Exposure Initiative, launched in 2011; and 4) the DBT Initiative, launched in 2012 to implement Dialectical Behavior Therapy. Each initiative has supported and financed ongoing training, consultation, and technical assistance. Published descriptions of the Beck Initiative capture the typical processes and procedures associated with the EBP initiatives (Wiltsey Stirman et al., 2015; Wiltsey Stirman, Buchhofer, McLaulin, Evans, & Beck, 2009). To date, DBHIDS has trained and supported over 500 therapists in over 50 programs and 10 levels of care across the initiatives. Though the costs associated with these efforts are substantial ($1–1.5 million annually for contracts to trainers), they generally account for less than 1% of DBHIDS’ operating budget, and have been largely funded through reinvestment funds as described in Footnote 1. Philadelphia’s efforts to implement EBPs in community settings are unique given their scope, intensity, and integration with broader system transformation efforts. The following sections provide examples of how DBHIDS has addressed each level of the policy ecology through the use of targeted strategies.

Some of these are implementation strategies (Powell et al., 2012; Powell, Waltz, et al., 2015) such as training and consultation, whereas others, such as interventions to reduce stigma, are components of the broader tapestry of strategies that are intended to transform Philadelphia into a recovery-oriented system of care. While more distally related to EBPs, we echo Raghavan et al.’s (2008) argument that this latter set of strategies is no less important in creating a fertile context for the implementation of EBPs. The full range of strategies and the barriers that they are intended to address are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Philadelphia’s effort to address the “policy ecology”

| Level: | Strategies: | Barrier(s) Addressed: |

|---|---|---|

| Organizational |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Difficulty tracking EBP adoption for purposes of quality monitoring and incentives | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Agency |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Political |

|

|

|

|

|

| Social |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Strategies to Address the Organizational Level

There are a number of barriers to implementing EBPs at the organizational-level, including (but certainly not limited to) variable organizational cultures and climates (Beidas et al., 2014; Glisson et al., 2008), implementation climates (Weiner, Belden, Bergmire, & Johnston, 2011), and leadership (Aarons, Ehrhart, & Farahnak, 2014a); lack of access to ongoing training, supervision, and consultation (Ganju, 2003; Manuel, Mullen, Fang, Bellamy, & Bledsoe, 2009; Powell, Hausmann-Stabile, & McMillen, 2013; Shapiro, Prinz, & Sanders, 2012); turnover of staff and leadership (Beidas, Marcus, Benjamin Wolk, et al., 2015), and inadequate financial supports (Hoagwood, 2003; Isett et al., 2007; Stewart et al., 2016). DBHIDS has used a number of strategies to support provider organizations and assist in covering the marginal costs of implementation (Raghavan, 2012; Raghavan et al., 2008), allowing organizations to invest more fully in the adoption, implementation, and sustainment of EBPs. Specifically, DBHIDS has supported organizations by: forming a coordinating body to oversee the implementation of EBPs and provide ongoing support to organizational leaders and clinicians, dedicating EBP coordinators to support implementation, providing financial support for training and consultation in EBPs (including lost staff time), providing continuing education units (CEUs) and other educational opportunities within the system, piloting the use of enhanced rates for EBPs and the use of claims modifiers to track the adoption of EBPs, monitoring fidelity to EBPs, and providing support for general organizational health and functioning.

Evidence-Based Practice and Innovations Center

The aforementioned EBP initiatives generated rich insights into what it takes to effectively implement innovative practices in public behavioral health. Deriving generalizable insights across EBPs remains a tremendous challenge given that the structures and requirements for training, consultation, and other implementation supports vary from EBP to EBP; however, DBHIDS quickly recognized that each individual effort could benefit from cross-fertilization and institutional learning. This need for a coordinated and centralized infrastructure to support the implementation and sustainment of EBPs (Beidas, Aarons, et al., 2013) led to the development of the Evidence-Based Practice and Innovation Center (EPIC), which is comprised of a director, EBP-specific coordinators, academic partners, and leaders from DBHIDS. The EPIC director provides overarching leadership of the city’s EBP implementation efforts, supports the EBP coordinators (described below), ensures continuity and efficiency between EBP initiatives, and engages a wide range of stakeholders to accomplish goals related to EBP implementation. EPIC provides strategic support to all EBP initiatives and is responsible for developing and maintaining relationships with treatment developers, community organizations, and other implementation stakeholders.

EPIC’s role is not limited to the EBP initiatives. For example, by examining barriers to successful implementation across initiatives, EPIC has identified “general capacities” in organizations (e.g., supervision, leadership, engagement, etc.) that may need to be developed separately from initiatives or serve as a foundation for EBPs. Developing these general capacities in a network of over 200 provider organizations (many of which have multiple programs) presents a challenge, and raises important questions about the appropriate sequencing of capacity building efforts (i.e., Is it best to build general capacities first and then attempt to implement EBPs or should this occur simultaneously?). One of EPICs ongoing objectives is to develop effective and efficient ways of building the capacity of provider organizations to implement effective services. In addition to operating on the organizational level, through system-wide activities EPIC addresses other levels of the policy ecology framework such as addressing social barriers to EBP implementation by providing general education and communication about EBPs (what they are and why they are important) and initiating dialogue about the use of evidence to inform programmatic decisions. Through education and programming, EPIC also attempts to operate on the political and social levels by addressing negative attitudes surrounding academia and how it translates into the surrounding urban communities. Academic and system leaders provide continuous feedback pertaining to the processes of implementing EBPs and the overall strategic direction of EPIC.

EBP coordinators

The EBP coordinators for each initiative typically have clinical experience related to the specific intervention being implemented, and act in a role that is similar to an external facilitator (Kauth, Sullivan, Cully, & Blevins, 2011; Mental Health QUERI, 2014). Indeed, the EBP coordinators fulfill a number of roles that align closely to published descriptions of external facilitators, as they are tasked with: (1) understanding the setting, (2) engaging stakeholders, (3) setting program goals, (4) providing evidence for the EBP and/or corresponding implementation strategies, (5) developing processes to inform implementation, (6) identifying problems and strengths, and (7) linking to outside resources (Mental Health QUERI, 2014). As intermediaries between DBHIDS, treatment developers, and provider organizations, EBP coordinators are uniquely positioned to address implementation issues that are at the level of the provider organizations or the system, and to use the resources available in other DBHIDS units (e.g., clinical network development, compliance training) to support implementation. This enables treatment developers to focus on clinical and EBP related challenges.

Funding training, consultation, and technical assistance

DBHIDS has fully funded training in EBPs, and in some cases, paid for clinicians’ time to attend training. This addresses an important implementation barrier, as it is often not feasible to ask clinicians in the public sector, to self-finance robust training (Powell, McMillen, Hawley, & Proctor, 2013; Stewart & Chambless, 2010). Since training is necessary but not sufficient to promote provider behavior change (Beidas, Edmunds, Marcus, & Kendall, 2012; Forsetlund et al., 2009; Herschell, Kolko, Baumann, & Davis, 2010), DBHIDS has also paid for ongoing consultation and technical assistance from the treatment developers and purveyors. DBHIDS has identified and selected a relatively limited number of EBPs for its major initiatives, some of which may not fit the contexts or clinical needs of providers. Thus, a future direction is to develop opportunities to encourage provider organizations to seek out and invest in training efforts for additional EBPs that may fit their unique circumstances.

Offering CEUs and shaping them toward EBPs

Organizations and clinicians are often highly motivated by the opportunity to receive continuing education credits (Powell, McMillen, et al., 2013), and many organizations are not able to offer many in-house or external opportunities for their clinicians to earn CEUs. DBHIDS has capitalized on licensed clinicians’ motivation to obtain CEUs and addressed organization barriers to their provision in two ways. It has provided CEU credits through each of its EBP initiatives, and has contracted with the Behavioral Health Training & Education Network (BHTEN) to provide training in recovery-oriented care (Abrahams et al., 2013) and a variety of EBPs. Thus, organizations and clinicians involved in the EBP initiatives have reaped immediate benefits of participation, and the entire system has benefited from the increased availability of EBP trainings in the continuing education curricula. This potential incentive is dampened for mental health professionals who are not licensed and thus are not motivated by CEUs.

Providing enhanced rates for EBPs

DBHIDS has provided enhanced rates to incentivize the implementation of certain EBPs. For instance, DBHIDS has provided an enhanced rate for outpatient providers participating in a SAMHSA-funded training who delivered TF-CBT. The provision of enhanced rates is being extended to other interventions with increasing levels of rigor and sophistication. For example, DBHIDS is working with DBT purveyors to ensure that enhanced payments are based upon meeting appropriate clinical and program criteria. DBHIDS has also begun to take steps to ensure that their data management and claims systems can be used to track the provision of EBPs, which will provide a stronger basis for incentivizing EBP adoption and sustainment through enhanced rates, pay-for-performance, and other mechanisms. Admittedly, existing capacity for tracking the provision of EBPs is limited; thus, this is a major priority moving forward. While there is a need for more research on the impact of financial incentives at all levels (system, provider, and clinician), some studies in behavioral health have demonstrated that they are effective in increasing clinicians’ intentions to deliver high quality treatment (Garner, Godley, & Bair, 2011) and the competent delivery of EBPs (Garner et al., 2012).

Monitoring fidelity to EBPs

Providing enhanced rates for EBPs introduces the challenge of ensuring some level of fidelity to the model, a significant challenge in community settings (Schoenwald, 2011). Participants in the Beck Initiative submit audio recordings, and fidelity is assessed using the Cognitive Therapy Rating Scale (Young & Beck, 1980). Similarly, participants in the DBT and Prolonged Exposure training initiatives submit audio recordings and receive expert feedback to ensure fidelity. DBHIDS is currently piloting a strategy to verify comprehensive delivery of DBT services by examining program operations and documentation as indicators of fidelity. Measuring fidelity remains a challenge that DBHIDS is working to address. Of particular concern is the development of an approach to consistently monitor fidelity across multiple EBPs that can be implemented efficiently, as research based approaches such as direct observation may be too time intensive (Schoenwald, 2011; Schoenwald et al., 2011). Ideally, such an approach would not require ongoing expert consultation, but would be integrated into the existing monitoring functions of DBHIDS (e.g., compliance) and directly tied to efforts to track and finance care delivery.

Providing support for organizational change

Finally, DBHIDS has provided support for the general organizational health and functioning of the members of its provider network. The Network Development division of DBHIDS bolsters staff and organizational infrastructure for providing quality clinical services by providing training in assessment, treatment planning, chart documentation, and supervision, all of which can be seen as prerequisites to delivering an EBP and developing a learning organization (Austin, 2008). NIATx, an organizational intervention based upon engineering principles that was developed at the University of Wisconsin (CHESS/NIATx, 2015), was also used within the system to improve access to and continuation of mental health and substance abuse treatment while reducing wait times and “no shows.” NIATx has resulted in a number of improved outcomes such as reduced wait times, increased admissions, and increased retention/continuation of services (Korczykowski, 2014). Though these outcomes are not directly tied to the provision of EBPs, they pave the way for more effective services and are integral to providing recovery-oriented care. In fact, concerns about the overall cultures and climates (Glisson et al., 2008; Glisson & Williams, 2015), fiscal health, and general functioning of provider agencies has led to discussions within EPIC about whether more intensive organizational interventions (e.g., ARC; Glisson et al., 2010) or support pertaining to business practices (e.g., New York State’s efforts; Hoagwood et al., 2014) might be necessary and appropriate.

Strategies to Address the Regulatory and Purchasing Agency Level

Regulatory and purchasing agencies, such as DBHIDS, provide the next level of context for the delivery of mental health services. There are many challenges inherent to this level, such as funding the transition period and accounting for high start-up costs when an EBP is initially introduced, the alignment of financial incentives/disincentives, and ensuring that services are reimbursable and that rate structures are adequate (Ganju, 2003; Isett et al., 2007; Magnabosco, 2006). As both a regulator and purchaser of mental health services in the City of Philadelphia (see Footnote 1), DBHIDS has utilized a number of strategies to increase the use of EBPs and improve the quality of behavioral health services, including: profiling providers who provide EBPs, fostering a culture of EBP, eliminating barriers to reimbursement for EBPs, and enhancing the quality of care by contracting for appropriate services.

Profiling organizations that provide EBPs

DBHIDS recently began to profile organizations within their network that provide EBPs. Only providers who have obtained formal training (through the EBP initiatives or other department verified training efforts) and are actively implementing a given EBP are listed on the DBHIDS website (http://dbhids.org/epic). The list of EBPs and providers who deliver them is intended to serve several purposes: (1) it is a resource for individuals and families seeking services as well as clinicians, organizations, and DBHIDS staff members wishing to refer to EBP-specific services; (2) it provides a means of assessing Philadelphia’s capacity to deliver EBPs to diverse populations and geographic locations; and (3) it serves to incent the delivery of EBPs by providing public recognition to those organizations that do so. The last point is important, as stakeholders in other systems have identified the lack of role models who are also using EBPs as an implementation barrier (Powell, Hausmann-Stabile, et al., 2013); profiling providers in this way can potentially foster healthy competition and collaboration between organizations (Bunger et al., 2014).

Fostering a culture of EBP

DBHIDS is working to foster a culture of EBP both internally and externally. One way of ensuring that EBPs are promoted from within is by making sure that cares managers and other DBHIDS staff members and system stakeholders are well informed about EBPs. This has involved providing DBHIDS staff members with training in the foundational elements of and rationale for EBP and implementation (e.g., levels of evidence, assessing the quality of research studies, how implementation research differs from clinical research). This training was provided through a public-academic collaboration with the University of Pennsylvania, and served to ensure that there was a common starting point for discussions about EBP implementation in the system. DBHIDS is also working to ensure care managers and other staff members are aware of the system’s present capacity to deliver specific EBPs by exposing them to EBP providers through the aforementioned lists and through public events. For example, DBHIDS organizes a monthly collaborative case conference series where EBP providers from the network collaborate with trainers and/or treatment developers to present a clinical case that demonstrates the unique aspects of the EBP and how it is implemented in the network. Another example is a recently held public event celebrating the EBP culture in Philadelphia, and providing organizations the opportunity to share their successes and challenges in implementing EBPs in Philadelphia.

Removing barriers to reimbursement

While there is evidence to suggest that the use of EBPs can result in faster improvement (e.g., Weisz et al., 2012), EBPs are not always briefer or less costly than alternative treatments. DBHIDS has attempted to eliminate barriers to EBP implementation by advocating for a wide array of evidence-based services to be billed under Medicaid, including those that differ structurally from traditional individual and group therapy (e.g., allowing for unlimited outpatient sessions and the ability to bill for more than 60 minute sessions). This pragmatic necessity is consistent with other large-scale implementation efforts (Isett et al., 2007; Magnabosco, 2006).

Issuing requests for proposals for the provision of EBPs

Finally, DBHIDS has attempted to increase the adoption and sustainment of EBPs by developing a systematic request for proposals (RFP) process. The RFPs describe the policies, procedures, and resources that organizations need to establish in order to implement an EBP well, and also detail the implementation and sustainment supports provided by DBHIDS. The process allows DBHIDS and applicant organizations to carefully assess the issues of innovation-values fit (Klein & Sorra, 1996) and organizational readiness for change (Weiner, 2009), and ultimately, make strategic decisions about the types of organizations that should be invited to participate in the EBP initiatives.

Using the Getting to Outcomes® framework for contracting new services

DBHIDS is also amplifying the expectations for the delivery of EBPs and the monitoring of outcomes in procurements for new services by reforming the procurement and contracting model using the Getting to Outcomes® framework (Chinman, Imm, & Wandersman, 2004). This involves ten steps: identifying needs and resources; setting goals and objectives to meet the needs; selecting an EBP; ensuring that the EBP fits the organization; assessing what capacities are needed to implement the program; creating and implementing a plan; evaluating the quality of implementation; evaluating how well the EBP worked; determining how a continuous quality improvement process could improve EBP delivery; and taking steps to ensure sustainability (Pipkin et al. 2013). DBHIDS is currently piloting the use of the Getting to Outcomes® framework in the procurement of substance use partial hospitalization services, which resulted in an RFP that placed a greater emphasis on tracking outcomes and the inclusion of specific EBPs within the service model (Community Behavioral Health, 2015). This process likely will lead to more thoughtful applications, facilitate better communication and fit between the needs and requirements of provider organizations and DBHIDS, improve implementation planning and execution, and enhance the tracking of outcomes.

Strategies to Address the Political Level

The legislative and advocacy efforts that support EBPs form the political context of implementation (Raghavan et al., 2008). DBHIDS’ primary strategies at the political level have been to avoid strict mandates and to build political support by engaging a wide range of stakeholders.

Avoiding strict mandates

Some systems have mandated the use of EBPs through legislative action. Indeed, Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research recently published a special issue focusing on legislation in Washington State that requires policy makers to utilize EBPs in publicly funded children’s behavioral health, juvenile justice, and child welfare (Trupin & Kerns, 2015). Legislative action of that sort can be a powerful lever for change, but Raghavan et al. (2008) urge policy makers to “carefully weigh the nature of the evidence, the availability of local resources to deliver the EBP with fidelity, and the unintended consequences of micromanaging care before considering such legislative strategies” (p. 5). In carefully weighing those factors, DBHIDS has taken a different approach by attempting to balance “top-down” and “bottom-up” approaches to the transformation, both of which have strengths and weaknesses (Nilsen, Stahl, Roback, & Cairney, 2013). While top-level leadership and support is indispensable, simply mandating change without input from other stakeholders is unlikely to be successful if system-level goals are not well-aligned with organizational and provider concerns and priorities (Aarons, Ehrhart, & Farahnak, 2014b; Lipsky, 1980; Nilsen et al., 2013). Indeed, in a recent study, “mandate change” was deemed to be relatively unimportant and infeasible as an implementation strategy by a sample of experts in the field (Waltz et al., 2015). Thus, EBPs were not required by legislative mandate, but were strongly encouraged and viewed as an integral component of the transformation effort (Abrahams et al., 2013). DBHIDS has attempted to carefully weigh the level of system-level support provided with expectations for the adoption and sustainment of EBPs. However, there is certainly political pressure for provider organizations to adopt EBPs, and there is some evidence to suggest that despite DBHIDS’ best efforts, both system and provider organization leaders have concerns that the EBP initiatives have felt mandatory and top-down (Beidas, Stewart, et al., 2015). This highlights the importance of engaging a wide range of stakeholders and taking a collaborative approach to implementation (Chambers & Azrin, 2013; Kirchner et al., 2014; Palinkas, Short, & Wong, 2015).

Building political support by engaging a wide range of stakeholders

DBHIDS has engaged a wide range of advocates and consumers to guide the transformation effort and the implementation of EBPs. This includes individuals who experience behavioral health disorders and their family members (Birkel, Hall, Lane, Cohan, & Miller, 2003); clinicians, peer-support specialists, staff, and administrators from provider organizations; treatment developers and purveyors; academic partners; and legislators and payers. The Transformation Practice Guidelines (Abrahams et al., 2013) that provide the overarching direction for Philadelphia’s improvement efforts represent the collective work of these stakeholder groups, and their voices reverberate throughout that document. These groups have been involved in a number of advisory boards and taskforces that have shaped EBP implementation efforts in the city and been important in garnering broad political support. Efforts have also been made to assuage some of the documented fears of consumer groups that are specific to the implementation of EBPs (Raghavan et al., 2008), such as explicitly linking EBP implementation efforts with the recovery transformation, ensuring that EBPs don’t replace other needed services, increasing the stock of providers capable of delivering EBPs to work toward access and equity in care, and working to ensure that care is culturally appropriate and empowering (Abrahams et al., 2013). Attitudes toward and climates for EBP implementation vary across the system (Beidas, Marcus, Aarons, et al., 2015), but liberal invitations for input have been a central part of every initiative and implementation related effort. Once again, the public event that celebrated the use of EBP within the Philadelphia system is one example of a strategy that is intended to promote broad learning and buy-in, and is a good example of the inclusive, participative approach that DBHIDS has attempted to use in order to galvanize stakeholders.

Strategies to Address the Social Level

Raghavan and colleagues (2008) discuss the role of stigma, discrimination, and other social barriers in preventing access to EBPs (Goffman, 1963; Gulliver, Griffiths, & Christensen, 2010). Many of these factors are not directly related to the implementation of EBPs; however, they serve as key barriers to the receipt of behavioral health services. There is limited value in scaling-up EBPs if individuals and families do not utilize services. Therefore, addressing stigma is central to the Transformation Practice Guidelines, with specific goals to “deliver services in non-stigmatized community settings” and to “join and initiate efforts to decrease stigma throughout all service systems” (Abrahams et al., 2013, p. 89 and 119). DBHIDS has used several strategies to mitigate the effects of stigma and reduce barriers to help seeking. As part of their broader public health approach to behavioral health, they have launched public events and public art focusing on behavioral health and recovery, have formed community coalitions to address the unique needs of specific populations at high risk of behavioral health problems, have adopted assessment and intervention approaches that are more easily accessible than formal professional services, and have supported a robust peer-support community.

Raising awareness and reducing stigma through public events

DBHIDS has sponsored or co-sponsored events that combat the effects of stigma and celebrate recovery. The annual PRO-ACT Recovery Walks! events are one example (PRO-ACT, 2015). In 2014, over 23,000 people walked in solidarity, sending a powerful message that those who experience behavioral health challenges are not alone. Philadelphia has showcased the talents of individuals in recovery since 2011 in their annual Recovery Idol event (DBHIDS & PRO-ACT, 2015), which includes several rounds of competition culminating in the finale that takes place at the Recovery Walks!.

Using public art to raise awareness and reduce stigma

DBHIDS has also partnered with the City of Philadelphia’s Mural Arts Program to develop the Porch Light Program (City of Philadelphia Mural Arts Program, 2015; Mohatt et al., 2013; Tebes et al., 2015). This program “works closely with communities to uplift public art as an expression of community resilience and a vehicle of personal and community healing” (City of Philadelphia Mural Arts Program, 2015). Murals focusing on mental health, substance use, and related themes such as faith and spirituality, homelessness, trauma, immigration, war and community safety tensions are constructed by teams of artists, service providers, program participants, and community members.

The program strives to catalyze positive changes in the community, improve the physical environment, create opportunities for social connectedness, develop skills to enhance resilience and recovery, promote community and social inclusion, shed light on challenges faced by those with behavioral health issues, reduce stigma, and encourage empathy (City of Philadelphia Mural Arts Program, 2015).

In the past two years, the Porch Light program has worked with nearly 400 program participants and over 3,000 community members. A recent evaluation of the Porch Light program reported a number of positive community-level effects (Tebes et al., 2015). Over the course of approximately one year, residents living within one mile of newly installed murals reported increases in collective efficacy, neighborhood aesthetic quality, and perceived safety, and decreases in stigma toward individuals with behavioral health challenges (Tebes et al., 2015). After two years, residents living within a mile of more than one newly installed mural reported a sustained increase in collective efficacy, an increase in perceptions of neighborhood aesthetic, and a decrease in stigma (Tebes et al., 2015).

Community Coalitions

The Community Coalition Initiative is intended to enhance the quality of behavioral health care for specific communities that may have substantial numbers of vulnerable or at-risk individuals (Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual disAbility Services, 2015c). There are seven different coalitions of community-based organizations and licensed behavioral health providers to help reach community members who can most benefit from behavioral health services. Examples of the coalitions include the Asian Wellness Coalition and the Youth of Promise Coalition. The coalitions play a role in the policy ecology for implementation by focusing on several specific areas, such as increasing access to behavioral health services for LGBTQI individuals, particularly those involved in sex work and/or drug use; violence prevention and drug and alcohol education for youth; increasing accessible behavioral health services; reducing stigma related to behavioral health issues; providing recovery-oriented support programs; and empowering and motivating leadership in local communities.

Interventions to improve access to behavioral health services

DBHIDS has implemented and piloted a number of public health interventions intended to increase knowledge about behavioral health and increase access to assessment and treatment. One example is the Healthy Minds Philly website, which provides information about behavioral health challenges, links to both online and community behavioral health screening, access to a 24-hour suicide crisis & intervention line, information about how to access services and supports, an events calendar, and a public health blog (City of Philadelphia Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual disAbility Services, 2014). Philadelphia is also providing free training for anyone who lives, works, or studies in Philadelphia in Mental Health First Aid (Kitchener & Jorm, 2006), which teaches individuals skills needed to identify, understand, and respond to behavioral health challenges. Certifications in Mental Health First Aid are available for different populations/settings, including adult, youth, public safety, veterans, and higher education. Philadelphia has also piloted the use of kiosks that provide access to free behavioral health screenings in retail (e.g., at a large-scale grocery store) and university settings. Finally, DBHIDS has piloted the use of Beating the Blues, a computer-delivered, full course cognitive-behavioral therapy intervention that addresses mild to moderate depression and anxiety (Proudfoot, 2004). The intervention consists of nine sessions, including an introductory video and eight 50-minute CBT sessions with homework activities between sessions. It was introduced to provide an alternative to traditional treatment modalities and increase the number of people in the community receiving care for depression and anxiety. It may also prove to be a gateway to more intensive treatment if needed. Importantly, this treatment modality may address the workforce challenge of training an adequate number of providers to competently deliver CBT, as it reduces the number of trained professionals required to treat mild to moderate depression and anxiety.

Leveraging the peer support community

Philadelphia has leveraged the perspective of people with lived experience to help others on their path to recovery through the Certified Peer Specialist program, which was developed by DBHIDS, the Pennsylvania Recovery Organization-Achieving Community Together (PROACT), and the Mental Health Association of Southeast Pennsylvania. Individuals with behavioral health challenges have the opportunity to become certified through a two-week training program that focuses on peer support, communication skills, cultural competency, conflict management, crisis intervention, and facilitating self-help groups. Certified Peer Specialists are then hired by provider agencies, and are provided technical assistance and job readiness training to promote a successful transition to the working world. Since the programs inception in 2006, over 500 Peer Specialists have been trained and certified (Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual disAbility Services, 2015b). The addition of peer support services to traditional behavioral health services has been associated with a number of positive outcomes, many of which directly or indirectly pertain to the ability to deliver evidence-based care, including reduced inpatient service use, improved relationship with providers, better engagement with care, higher levels of empowerment, higher levels of patient activation, and higher levels of hopefulness for recovery (Chinman et al., 2014).

Ongoing Challenges, Opportunities, and Lessons Learned

We have used the City Of Philadelphia as a case example to demonstrate that numerous strategies across multiple socioecologic levels may be necessary to implement EBPs well. Concrete examples of how these implementation strategies can address barriers and leverage facilitators to directly or indirectly increase the chances that implementation and quality improvement efforts are successful have been provided (see Table 1 for a summary). These examples expand upon the work of Raghavan et al. (2008) to suggest how a single system can adopt a holistic, comprehensive approach to implementing EBPs and addressing quality concerns. The fact that multiple strategies are needed to improve care in large public behavioral health systems is consistent with the extant literature (e.g., Aarons et al., 2011; Glisson et al., 2010; Hoagwood et al., 2014; Isett et al., 2007; Magnabosco, 2006; Novins et al., 2013; Powell et al., 2014). Strategies at different levels of the policy ecology may be interdependent and mutually reinforcing, and the EPIS framework (Aarons et al., 2011) and empirical work detailing implementation strategy use in public behavioral health (Isett et al., 2007; Magnabosco, 2006) suggest that different strategies may be more or less important depending upon the phase of implementation. We join Raghavan et al. (2008) in urging policymakers, administrators, and implementation researchers in public behavioral health and other public service sectors to carefully consider the policy ecology for implementation and to avoid rash decisions to mandate EBPs without aligning supports across all four levels (i.e., organizational, regulatory and purchasing, political, social). Philadelphia’s efforts can serve as one model; however, we highlight a number of challenges, opportunities, and lessons learned that we believe will be instructive for other public behavioral health systems, including the importance of selecting providers wisely; moving from stand-alone initiatives to infrastructure; conceptualizing and aligning large-scale, multi-level, multifaceted implementation strategies; evaluating implementation and clinical outcomes; and learning from other systems.

Selecting Providers Wisely

An enduring lesson from DBHIDS implementation efforts is the importance of carefully selecting provider organizations to participate in the EBP initiatives. When the EBP initiatives began, the selection of organizations to participate did not involve in-depth assessments or discussions to determine the fit between the goals of involved stakeholders. As a result, the expectations and requirements of DBHIDS were not fully articulated, nor were the supports available to participating organizations adequately described. Organizations may have volunteered to participate in the initiatives because it was politically expedient, and they may not have fully weighed the costs and benefits of participation (Beidas, Stewart, et al., 2015). Ultimately, forming partnerships capable of facilitating implementation and sustainment has required seizing multiple opportunities to assess the fit between stakeholders. It has been important to consider the types of EBPs that will fit with providers given the populations they serve and the levels of care they provide, ensuring that the EBPs would address one of their concrete needs (Chorpita & Daleiden, 2009; Chorpita, Daleiden, & Weisz, 2005). It was necessary for DBHIDS to know provider organizations intimately, including their procedures (e.g., referral/intake, therapist assignment, and assessment), therapists’ qualifications and prerequisite training and skills for the EBPs, and the organizations’ social context and attitudes toward EBPs. It was also important to assess barriers and facilitators, and to learn from those identified in the past. Barriers related to assessment, identifying appropriate referrals, maintenance of waitlist, marketing materials, and billing for all components of the EBP model (e.g., supervision, peer group case reviews, etc.) were particularly salient.

Several strategies have been useful in determining the fit between stakeholders and the EBP initiatives, including a careful assessment of organizational capacity through an initial request for proposals (RFP) process, interviews, pre-training meetings, and update sessions. As described above, this process has become increasingly sophisticated over time, as DBHIDS is currently piloting the use of the Getting to Outcomes ® framework (Chinman et al., 2004) to guide the RFP process (Community Behavioral Health, 2015). Scheduling time to discuss provider organizations’ responses to RFPs has been invaluable. Giving organizations the opportunity to describe their program, the population(s) they serve, and their process for implementation has yielded vital information that was not apparent in written applications and has given DBHIDS a better sense of organizations’ levels of commitment as well as ongoing needs for support. Continuing to hold meetings with DBHIDS, providers, and treatment developers/purveyors after the initiative begins has ensured that there continues to be a solid fit from all stakeholders’ perspectives. In some cases there has been a need to create opportunities for stakeholders to “exit gracefully” from an EBP initiative. Rather than viewing this as failure, this has been seen as a prudent decision that benefits all stakeholders by preventing large investments of time and money in efforts that are unlikely to be successful.

Moving from Stand-Alone Initiatives to Infrastructure

DBHIDS implementation efforts began with a very traditional approach with heavy focus on training and a relatively narrow focus on individual EBP initiatives, but it quickly became apparent that meaningful system-wide change would require substantial shifts away from stand-alone initiatives and toward building infrastructure for EBPs at the provider organization level. Three shifts in perspective have been important. First, DBHIDS has attempted to shift from focusing on therapists to organizations. This stems from recognition that therapists need support from all levels of their organization in order to deliver EBPs well, that turnover presents a major threat to EBP adoption and sustainment (Beidas, Marcus, Benjamin Wolk, et al., 2015), and that the system in Philadelphia is organized around provider organizations rather than individual clinicians. In addition to selecting provider organizations carefully using the aforementioned RFP process, DBHIDS has worked hard to engage supervisors, administrators, and executive directors in the implementation process through regular meetings and training opportunities. Engaging these multiple levels of leadership is an important area of ongoing work, both for DBHIDS and the broader field of implementation research (Aarons et al., 2014a; Birken, Lee, Weiner, Chin, & Schaefer, 2013; Dorsey et al., 2013; Glisson & Williams, 2015). Second, DBHIDS has shifted from focusing on individual practices to programs by finding ways to encourage organizational buy-in and accountability for delivering particular EBPs at the provider organization level. For example, using rostering and other forms of public recognition (e.g., the organizations providing EBPs are now listed online) to bolster provider organizations’ reputations for particular EBP programs may enhance their referral networks and resources, and ultimately buffer against turnover by placing the locus of expertise at the program level. An ongoing challenge is to develop the organizations’ and system’s capacity to deliver multiple EBPs, which fits within Chambers’ (2012) call for a focus on “evidence-based systems of care rather than the individual intervention” (p. ix). Finally, DBHIDS has attempted to make a shift from EBPs being viewed as “add-ons” to being well integrated within the broader system. For both DBHIDS and provider organizations, focusing on initiatives sent implicit messages that the implementation efforts were “optional,” “temporary,” or an “extra project.” This created threats to ownership and accountability, and also increased the odds that individual initiatives would be siloed. The strategies for accomplishing this integration have been highlighted throughout this article, and have included efforts to leverage tracking and billing systems, educating in-house DBHIDS staff about the importance of specific EBPs, aligning procurement and contracting processes to support EBP implementation, creating a registry of providers that deliver EBPs, and attempting to develop outcomes tracking and reporting processes. Implementing EBPs does not fix broader system problems. On the contrary, attempting to implement EBPs may accentuate problems at the organizational, agency, political, and social levels. It is clear that infrastructure at each of these levels must be built if EBPs are to be adopted and sustained in public behavioral health (Beidas, Stewart, et al., 2015).

Conceptualizing and Aligning Complex, Multi-Level Implementation Strategies

The complexity of implementing multiple EBPs and aligning system-level implementation strategies is tremendously challenging. The pace of change and myriad competing demands often preclude system leaders’ and other stakeholders’ ability to carefully conceptualize an implementation approach and ensure that the strategies they employ are synergistic. The formation of EPIC (and the associated convening of system leaders and academic stakeholders) has certainly increased the bandwidth available to engage in strategic planning. However, the use of formal frameworks, modeling approaches, and reporting tools may assist in becoming more systematic and transparent about the various implementation efforts and associated implementation strategies. For instance, it may be useful to use a multilevel framework such as the policy ecology framework (Raghavan et al., 2008) or EPIS model (Aarons et al., 2011) to prospectively plan and track implementation across levels and phases or to identify the strengths and weaknesses of an implementation approach retrospectively. Formal modeling approaches, ranging from logic models (Goeschel, Weiss, & Pronovost, 2012; W. K. Kellogg Foundation, 2004) and causal modeling frameworks (Weiner, Lewis, Clauser, & Stitzenberg, 2012) to more complex approaches like system dynamics modeling (Hovmand, 2014; Lyon, Maras, Pate, Igusa, & Vander Stoep, 2015; Powell, Beidas, et al., 2015) could be used to combine implementation strategies at multiple levels and study their effects. Finally, taxonomies of implementation strategies (e.g., Michie et al., 2013; Powell, Waltz, et al., 2015) and formal reporting guidelines designed to inform the reporting of implementation strategies in the published literature (e.g., Albrecht, Archibald, Arseneau, & Scott, 2013; Proctor, Powell, & McMillen, 2013) could be used to carefully document system-level implementation strategies. Each of these approaches would go a long way in ensuring that systems are deliberate in selecting and tailoring implementation strategies (i.e., Why did we take this approach?) and that the strategies actually used are carefully documented so that systems can learn from successes and failures (i.e., What did we actually do and did it work?).

Assessing Implementation and Clinical Outcomes

DBHIDS is one of the first large systems to actively support the implementation of EBP through coordinated initiatives, none of which were primarily research-based. The system prioritized providing broader access to EBPs for underserved individuals and families rather than choosing to pursue smaller initiatives with more robust evaluation designs. Thus, DBHIDS has continued to grapple with defining and measuring success for its implementation efforts. To truly understand the impact of the initiatives, measuring therapist fidelity to EBPs and clinical outcomes in consumers receiving these EBPs is necessary. DBHIDS has attempted to track both implementation and clinical outcomes in some of the individual EBP initiatives (e.g., the Beck and DBT initiatives). Additionally, proxies for fidelity such as self-reported use of treatment techniques have been examined in the context of the behavioral health transformation effort (Beidas, Aarons, et al., 2013; Beidas, Marcus, Aarons, et al., 2015), and further research has been proposed to assess various accurate and cost-effective approaches to measuring fidelity using behavioral rehearsal and chart simulated recall (Beidas, Cross, & Dorsey, 2013; Jennett & Affleck, 1998). However, the absence of an overarching evaluation design and the inability to track implementation and clinical outcomes across all of the EBP initiatives remains a substantial limitation. This challenge does not seem to be unique to Philadelphia, as to our knowledge no large system has been able to routinely measure fidelity and clinical outcomes (Raghavan et al., 2008). At DBHIDS, discussions continue about the most prudent way of measuring client-level outcomes in a way that is not overly burdensome and is clinically useful. It is encouraging that increasing attention is being given to measurement feedback systems in mental health, but these systems are innovations themselves that will require resources and unique implementation supports. Lyon and Lewis (2015) note that little empirical work has examined the strategies through which these systems are developed and implemented in behavioral health service settings. Moreover, we are not aware of any large system that has successfully implemented a measurement feedback system at the scale that would be required in Philadelphia. This represents an important area of future inquiry, and an upcoming special section of this journal includes empirical studies that shed light on these processes (Lyon & Lewis, 2015).

Another thorny problem is the evaluation of community-level interventions and strategies. In these cases, appropriate outcomes can be difficult to identify, distal, and diffuse. The aforementioned approaches to planning and capturing the complexity of multi-level implementation strategies is one way of addressing this problem. The use of qualitative and mixed methods designs is another, and DBHIDS’ academic partners have taken advantage of the explanatory power of these designs (Beidas et al., 2014; Beidas, Marcus, Benjamin Wolk, et al., 2015; Tebes et al., 2015; Wiltsey Stirman et al., 2015). Further work to specify and measure implementation contexts, processes, and outcomes in large public behavioral health systems is warranted (Lewis, Weiner, Stanick, & Fischer, 2015; Proctor, Powell, & Feely, 2014).

Learning from Other Systems

One challenge faced by all large systems attempting to implement EBPs widely are the limited opportunities to learn from other systems’ experiences. One avenue to learn from other systems is through the published literature, such as the national and state efforts described by McHugh and Barlow (2010), lessons learned from New York’s efforts to scale-up EBPs for children and families (Hoagwood et al., 2014), and community-partnered work in Los Angeles to improve depression care (Wells et al., 2013). This journal has made important contributions to these discussions over the years, including the recent publication of a special issue on Washington State’s efforts (Trupin & Kerns, 2015) and this special issue on system-level implementation. There may be a need, however, for more opportunities for active, dynamic learning opportunities. At a panel focused on system-level implementation at the Association for Cognitive and Behavioral Therapies’ 2015 meeting, Dr. Arthur Evans, Commissioner of DBHIDS, noted that there may be a unique opportunity to form learning collaboratives (Institute for Healthcare Improvement, 2003) that leverage the collective wisdom of system leaders and academic stakeholders nationwide. To our knowledge, no such collaborative exists. Some manifestation of that vision has the potential to expedite progress toward the widespread implementation and sustainment of EBPs in public behavioral health, and indeed, creating learning behavioral healthcare systems (Austin, 2008).

Conclusion

Change is most often hard fought. Gawande (2008) wrote, “We always hope for the easy fix: the simple one change that will erase a problem in a stroke. But few things in life work in this way. Instead, success requires making a hundred small steps go right – one after the other, no slip ups, no goofs, everyone pitching in” (p. 21). This manuscript illustrates the truth of that statement by sharing concrete strategies at the organizational, agency, political, and social levels that can be used to facilitate the implementation of EBPs. While much of the empirical work in implementation continues to focus at the individual clinician-level, it is unlikely that implementation efforts that focus on any single level in the absence of the others are likely to be successful given the importance of inner and outer context factors (Aarons et al., 2011; Beidas, Marcus, Aarons, et al., 2015; Glisson & Williams, 2015; Novins et al., 2013). Consistent with the conceptual (Aarons et al., 2011; Damschroder et al., 2009; Tabak et al., 2012) and empirical literature (Hoagwood et al., 2014; Isett et al., 2007; Magnabosco, 2006), our experience suggests that multifaceted, multilevel implementation strategies are needed to facilitate the uptake of EBPs in large, publicly funded behavioral health systems. Our hope is that policymakers, administrators, and implementation researchers will be able to apply and carefully align some of the implementation strategies discussed in this article, and that they would also learn from some of DBHIDS’ challenges as they develop innovative strategies of their own. We look forward to learning from other systems that are implementing EBPs, as we have much to learn about the types of implementation strategies and evaluation approaches that are efficient, effective, and sustainable in large publicly funded behavioral health systems.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by Philadelphia’s Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual disAbility Services through a fellowship to BJP, and by the National Institutes of Mental Health through a contract to BJP through the Clinical Research Loan Repayment Program, and grants to RSB (K23MH099179); RES (F32MH103960); CBW (F32MH103955); and DSM (R01MH106175).

Footnotes

Philadelphia’s decision making process and ultimate decision to create its own managed care organization rather than allow a private sector health maintenance organization to manage the behavioral health care of Medicaid recipients is documented elsewhere (Guckenberger, 2002). What is pertinent to this article is that by taking on the risk of managing Medicaid dollars at the city level, DBHIDS also benefits from any savings that they incur through the provision of more efficient and effective care. They are able to use these saving to reinvest in the system in ways that will improve the quality of behavioral health care for Medicaid recipients. Many of the efforts described in this article are funded in part through these reinvestment dollars.

Portions of this work were presented at the Society for Implementation Research Collaboration on September 26, 2015.

Contributor Information

Byron J. Powell, Department of Health Policy and Management, Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. This manuscript was conceptualized when Byron Powell was a postdoctoral fellow at the Center for Mental Health Policy and Services Research, Department of Psychiatry, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania.

Rinad S. Beidas, Center for Mental Health Policy and Services Research, Department of Psychiatry, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania.

Ronnie M. Rubin, Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual disAbility Services.

Rebecca E. Stewart, Center for Mental Health Policy and Services Research, Department of Psychiatry, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania.

Courtney Benjamin Wolk, Center for Mental Health Policy and Services Research, Department of Psychiatry, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania.

Samantha L. Matlin, Thomas Scattergood Behavioral Health Foundation.

Shawna Weaver, Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual disAbility Services.

Matthew O. Hurford, Community Care Behavioral Health Organization.

Arthur C. Evans, Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual disAbility Services.

Trevor R. Hadley, Center for Mental Health Policy and Services Research, Department of Psychiatry, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania.

David S. Mandell, Center for Mental Health Policy and Services Research, Department of Psychiatry, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania.

References

- Aarons GA, Ehrhart MG, Farahnak LR. Aligning leadership across systems and organizations to develop a strategic climate for evidence-based practice implementation. Annual Review of Public Health. 2014a;35:255–274. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182447. http://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarons GA, Ehrhart MG, Farahnak LR. Aligning leadership across systems and organizations to develop a strategic climate for evidence-based practice implementation. Annual Review of Public Health. 2014b;35:255–274. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182447. http://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarons GA, Hurlburt M, Horwitz SM. Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2011;38:4–23. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0327-7. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-010-0327-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abrahams IA, Ali O, Davidson L, Evans AC, King JK, Poplawski P … Philadelphia Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual disAbility Services. Philadelphia behavioral health services transformation: Practice guidelines for recovery and resilience oriented treatment. Bloomington, Indiana: AuthorHouse Publishers; 2013. I.I. Retrieved from http://www.dbhids.org/assets/Forms--Documents/transformation/PracticeGuidelines2013.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht L, Archibald M, Arseneau D, Scott SD. Development of a checklist to assess the quality of reporting of knowledge translation interventions using the Workgroup for Intervention Development and Evaluation Research (WIDER) recommendations. Implementation Science. 2013;8(52):1–5. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-52. http://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-8-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin MJ. Strategies for transforming human service organizations into learning organizations: Knowledge management and the transfer of learning. Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work. 2008;5(3–4):569–596. doi: 10.1080/15433710802084326. http://doi.org/10.1080/15433710802084326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beidas RS, Aarons GA, Barg F, Evans A, Hadley T, Hoagwood K, … Mandell DS. Policy to implementation: Evidence-based practice in community mental health -- study protocol. Implementation Science. 2013;8(38):1–9. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-38. http://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-8-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beidas RS, Cross W, Dorsey S. Show me, don’t tell me: Behavioral rehearsal as a training and analogue fidelity tool. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2013.04.002. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Beidas RS, Edmunds JM, Marcus SC, Kendall PC. Training and consultation to promote implementation of an empirically supported treatment: A randomized trial. Psychiatric Services. 2012;63(7):660–665. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100401. http://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201100401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beidas RS, Marcus S, Aarons GA, Hoagwood KE, Schoenwald S, Evans AC, … Mandell DS. Predictors of community therapists’ use of therapy techniques in a large public mental health system. JAMA Pediatrics. 2015;169(4):374–382. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.3736. http://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.3736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beidas RS, Marcus S, Benjamin Wolk C, Powell BJ, Aarons GA, Evans AC, … Mandell DS. A prospective examination of clinician and supervisor turnover within the context of implementation of evidence-based practices in a publicly-funded mental health system. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10488-015-0673-6. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-015-0673-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Beidas RS, Stewart RE, Adams DR, Fernandez T, Lustbader S, Powell BJ, … Barg FK. A multi-level examination of stakeholder perspectives of implementation of evidence-based practices in a large urban publicly-funded mental health system. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10488-015-0705-2. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-015-0705-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Beidas RS, Wolk CB, Walsh LM, Evans AC, Hurford MO, Barg FK. A complementary marriage of perspectives: Understanding organizational social context using mixed methods. Implementation Science. 2014;9(175):1–15. doi: 10.1186/s13012-014-0175-z. http://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-014-0175-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birkel RC, Hall LL, Lane T, Cohan K, Miller J. Consumers and families as partners in implementing evidence-based practice. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2003;26:867–881. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(03)00065-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birken SA, Lee SYD, Weiner BJ, Chin MH, Schaefer CT. Improving the effectiveness of health care innovation implementation: Middle managers as change agents. Medical Care Research and Review. 2013;70(1):29–45. doi: 10.1177/1077558712457427. http://doi.org/10.1177/1077558712457427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunger AC, Collins-Camargo C, McBeath B, Chuang E, Perez-Jolles M, Wells R. Collaboration, competition, and co-opetition: Interorganizational dynamics between private child welfare agencies and child serving sectors. Children and Youth Services Review. 2014;38:113–122. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.01.017. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers DA. Forward. In: Brownson RC, Colditz GA, Proctor EK, editors. Dissemination and implementation research in health: Translating science to practice. New York: Oxford University Press; 2012. pp. vii–x. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers DA, Azrin ST. Partnership: A fundamental component of dissemination and implementation research. Psychiatric Services. 2013;64(16):509–511. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300032. http://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201300032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHESS/NIATx. NIATx: Removing barriers to treatment & recovery. 2015 Retrieved August 17, 2015, from http://www.niatx.net/

- Chinman M, George P, Dougherty RH, Daniels AS, Ghose SS, Swift A, Delphin-Rittmon ME. Peer support services for individuals with serious mental illnesses: Assessing the evidence. Psychiatric Services. 2014;65(4):429–441. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300244. http://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201300244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinman M, Imm P, Wandersman A. Getting to outcomes 2004: Promoting accountability through methods and tools for planning, implementation, and evaluation. Santa Monica, CA: Rand Health; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Daleiden EL. Mapping evidence-based treatments for children and adolescents: Application of the distillation and matching model to 615 treatments from 322 randomized trials. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77(3):566–579. doi: 10.1037/a0014565. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0014565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Daleiden EL, Weisz JR. Identifying and selecting the common elements of evidence based interventions: A distillation and matching model. Mental Health Services Research. 2005;7(1):5–20. doi: 10.1007/s11020-005-1962-6. http://doi.org/10.1007/s11020-005-1962-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- City of Philadelphia Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual disAbility Services. Healthy Minds Philly. 2014 Retrieved from http://healthymindsphilly.org.

- City of Philadelphia Mural Arts Program. Porch Light. 2015 Retrieved August 18, 2015, from http://muralarts.org/programs/porch-light.

- Community Behavioral Health. Request for proposals for substance use adult partial hospitalization services. 2015 Retrieved from http://www.dbhids.us/assets/Forms--Documents/CBH/RFP-Substance-Use-Adult-Partial-Hospitalization.pdf.

- Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science. 2009;4(50):1–15. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DBHIDS & PRO-ACT. Philadelphia Recovery Idol 2015. 2015 Retrieved August 20, 2015, from phillyrecoveryidol.weebly.com.

- Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual disAbility Services. Community Behavioral Health. 2015a Retrieved August 13, 2015, from http://dbhids.us/community-behavioral-health/

- Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual disAbility Services. Peer Specialist Initiative. 2015b Retrieved September 22, 2015, from http://dbhids.us/certified-peer-specialist.

- Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual disAbility Services. The Community Coalition Initiative. 2015c Retrieved September 23, 2015, from http://www.dbhids.us/the-community-coalition-initiative.

- Dorsey S, Pullman MD, Deblinger E, Berliner L, Kerns SE, Thompson K, … Garland AF. Improving practice in community-based settings: A randomized trial of supervision - Study protocol. Implementation Science. 2013;8(89):1–11. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-89. http://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-8-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsetlund L, Bjorndal A, Rashidian A, Jamtvedt G, O’Brien MA, Wolf F, … Oxman AD. Continuing education meetings and workshops: Effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009;2 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003030.pub2. http://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003030.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganju V. Implementation of evidence-based practices in state mental health systems: Implications for research and effectiveness studies. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2003;29(1):125–131. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner BR, Godley SH, Bair CML. The impact of pay-for-performance on therapists’ intentions to deliver high quality treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2011;41(1):97–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.01.012. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner BR, Godley SH, Dennis ML, Hunter BD, Bair CML, Godley MD. Using pay for performance to improve treatment implementation for adolescent substance use disorders. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 2012;166(10):938–944. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2012.802. http://doi.org/10.1001/archpediatrics.2012.802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawande A. Better: A surgeon’s notes on performance. New York: Picador; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Glisson C, Landsverk J, Schoenwald S, Kelleher K, Hoagwood KE, Mayberg S, Green P. Assessing the organizational social context (OSC) of mental health services: implications for research and practice. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2008;35(1–2):98–113. doi: 10.1007/s10488-007-0148-5. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-007-0148-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glisson C, Schoenwald S, Hemmelgarn A, Green P, Dukes D, Armstrong KS, Chapman JE. Randomized trial of MST and ARC in a two-level evidence-based treatment implementation strategy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78(4):537–550. doi: 10.1037/a0019160. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0019160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glisson C, Williams NJ. Assessing and changing organizational social contexts for effective mental health services. Annual Review of Public Health. 2015;36:507–23. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031914-122435. http://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031914-122435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goeschel CA, Weiss WM, Pronovost PJ. Using a logic model to design and evaluate quality and patient safety improvement programs. International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 2012;24(4):330–337. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzs029. http://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzs029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffman I. Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. New York: Simon & Schuster, Inc; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Guckenberger K. Public takes on private: The Philadelphia behavioral health system. Kennedy School of Government Case Program; 2002. pp. 1–20. No. C16-02-1649.0. [Google Scholar]

- Gulliver A, Griffiths KM, Christensen H. Perceived barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking in young people: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10(113) doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-10-113. http://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-10-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herschell AD, Kolko DJ, Baumann BL, Davis AC. The role of therapist training in the implementation of psychosocial treatments: A review and critique with recommendations. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30:448–466. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.02.005. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]