Abstract

Background

Childhood abuse is a major global and public health problem associated with a myriad of adverse outcomes across the life course. Suicide is one of the leading causes of mortality during the perinatal period. However, few studies have assessed the relationship between experiences of childhood abuse and suicidal ideation in pregnancy.

Objective

To examine the association between exposure to childhood abuse and suicidal ideation among pregnant women.

Study Design

A cross-sectional study was conducted among 2,964 pregnant women attending prenatal clinics, in Lima, Peru. Childhood abuse was assessed using the Childhood Physical and Sexual Abuse Questionnaire. Depression and suicidal ideation were assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 scale. Logistic regression procedures were performed to estimate adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals adjusted for potential confounders.

Results

Overall, the prevalence of childhood abuse in this cohort was 71.8% and antepartum suicidal ideation was 15.8%. The prevalence of antepartum suicidal ideation was higher among women who reported experiencing any childhood abuse compared to those reporting none (89.3% vs. 10.7%, P<0.0001). After adjusting for potential confounders, including antepartum depression and lifetime intimate partner violence, those with history of any childhood abuse had a 2.9-fold (adjusted odds ratios; 95% confidence intervals: 2.12-3.97) increased odds of reporting suicidal ideation. Women who experienced both physical and sexual childhood abuse had much higher odds of suicidal ideation (adjusted odds ratios =4.04; 95% confidence intervals: 2.88-5.68). Women who experienced any childhood abuse and reported depression had 3.44-fold (adjusted odds ratios; 95% confidence intervals: 1.84-6.43) increased odds of suicidal ideation compared with depressed women with no history of childhood abuse. Finally, the odds of suicidal ideation increased with increased number of childhood abuse events experienced (P-value for trend<0.001).

Conclusion

Maternal history of childhood abuse was associated with increased odds of antepartum suicidal ideation. It is important for clinicians to be aware of the potential increased risk of suicidal behaviors among pregnant women with a history of childhood physical and sexual abuse.

Keywords: childhood abuse, depression, suicidal ideation, pregnant women

Introduction

Approximately 275 million children per year suffer acts of violence in their own home 1. As many as 40 million children under 15 years of age in Latin America and the Caribbean countries have experienced violence, abuse, and neglect 1. Childhood abuse includes all forms of physical and psychological maltreatment that pose harm to a child’s health, development or dignity, and include physical abuse and sexual abuse 2. Notably, childhood abuse is rarely a solitary incident rather, it appears to co-occur with one or more types of childhood maltreatment (i.e., physical neglect, emotional neglect, and emotional abuse) 3, 4. Childhood abuse has been reported to be associated with adverse psychiatric and physical health conditions in adulthood 5,6,7-10. In pregnant women, exposure to childhood abuse has been associated with psychiatric disorders 6,11, sleep disturbances 12, health risk behaviors 13, and unfavorable pregnancy outcomes 14. However, few studies 15 have assessed the relationship between experiences of childhood abuse and suicidal ideation in pregnancy. Suicidal ideation and suicide attempt during pregnancy are associated with a myriad of adverse maternal and infant outcomes including psychiatric disorders such as depression, fetal growth restriction, premature labor, and cesarean delivery 11,16,17, 18,19. Notably, an emerging body of evidence now implicates suicidal ideation as a precursor and important predictor of later suicide attempts and completions 20. Given that suicide is one of the leading causes of mortality during the perinatal period 21, 22,23, 24 and given the gap in the existing literature, we conducted the present analysis, in a large pregnancy cohort, to assess the extent to which, if at all, women’s history of physical and/or sexual abuse in childhood is associated with antepartum suicidal ideation. Documentation of associations of childhood abuse with suicidal ideation in this population may have important clinical implications insofar as alerting health care providers to the need for evaluating and screening women for past abuse.

Materials and Methods

Participants in this cross-sectional study were women who received prenatal care at the Instituto Nacional Materno Perinatal (INMP) from February 2012 to March 2014 and who enrolled in the ongoing Pregnancy Outcomes, Maternal and Infant Study (PrOMIS) cohort study. The INMP is the main reference establishment for maternal and perinatal care operated by the Ministry of Health (MINSA) of the Peruvian government. Eligible participants were pregnant women who were 18–49 years of age and who were under 16 weeks of gestational age during the prenatal care visit. Participants were ineligible if they were younger than 18 years of age, did not speak and read Spanish, or had completed more than 16 weeks of gestation. Details of the study setting and data collection procedures have been described previously 11. Briefly, each participant was interviewed, in a private setting, by trained research personnel using a structured questionnaire. The questionnaire was used to elicit information regarding maternal socio-demographic, lifestyle characteristics, medical and reproductive histories, symptoms of depression and childhood abuse experiences. All participants provided written informed consent prior to interview. The institutional review boards of the INMP, Lima, Peru and the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health Office of Human Research Administration, Boston, MA approved all procedures used in this study.

Analytical Population

The study population for this report is derived from information collected from participants who enrolled in the PrOMIS Study. During the study period a total of 3,045 participants completed the structured interview. For the analysis described here, we excluded participants with missing information on suicidal ideation (N=37), history of childhood abuse (N=69), and symptoms of depression (N=21). The final analysis included 2,964 participants. Excluded participants did not differ from the rest of the cohort with regards to socio-demographic or lifestyle characteristics.

Childhood Abuse Assessment

The Childhood Physical and Sexual Abuse Questionnaire was used to collect information concerning participants’ experiences with physical and sexual abuse in childhood 25. Participants were categorized as having experienced childhood physical abuse if, before the age of 18 years, they reported that an older person hit, kicked, pushed, or beat them and/or their life was seriously threatened. Participants were categorized as having experienced childhood sexual abuse if, before the age of 18 years, they reported that an older person touched them, they were made to touch someone else in a sexual way, or someone attempted or completed intercourse with them. Participants who responded “no” to all questions regarding childhood sexual and physical abuse were categorized as having experienced “no abuse”.

Participants who experienced “any childhood physical or sexual abuse” were further classified into three groups: “childhood physical abuse only” if they only endorsed physical abuse questions, “childhood sexual abuse only” if they only endorsed sexual abuse questions, or “both childhood physical and sexual abuse” if they endorsed both physical abuse and sexual abuse questions. Furthermore, the frequency of childhood abuse events was assessed by summing responses to individual abuse questions and creating the following response categories: “0,” “1,” “2,” or “≥3.”

Lifetime Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) Assessment

Questions pertaining to intimate partner violence (IPV) were adapted from the protocol of Demographic Health Survey Questionnaires and Modules: Domestic Violence Module 26 and the World Health Organization (WHO) Multi-Country Study on Violence Against Women 27. Participants were assessed for several physical and/or sexual coercive acts used against them by a current or former spouse or intimate partner during their lifetime. A participant was classified as having experienced physical violence if she endorsed any of the following acts: being slapped or having something thrown at her; being pushed, shoved, or having her hair pulled; being hit; being kicked, dragged, or beaten up; being choked or burnt on purpose; and being threatened or hurt with a weapon (such as a gun or knife). A participant was classified as having experienced sexual violence if she endorsed any of the following acts: being physically forced to have sexual intercourse; having had unwanted sexual intercourse because of fear of what the partner might do; or being forced to perform other sexual acts that she found degrading or humiliating. In the present analysis, we categorized participants as having experienced either “no physical and sexual violence” or “any physical or sexual violence” during lifetime.

Depression and Suicidal Ideation Assessments

The Patient Health Quetsionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) is a nine-item depression screening scale based on the criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder-IV (DSM-IV) 28, 29. The questionnaire assesses nine depressive symptoms in the 14 days prior to evaluation. The PHQ-9 score is calculated by assigning a score of 0-3 to the response categories “not at all,” “several days,” “more than half the days,” and “nearly every day”. Suicidal ideation was assessed based on the PHQ-9 question inquiring as to patient having “thoughts that you would be better off dead or of hurting yourself in some way”. Participants responding to this question with “several days,” “more than half the days,” and “nearly every day” were categorized as affirmative for suicidal ideation. The question asking about suicidal ideation was not considered in the total score for depression. The first eight questions (PHQ-8) were used to calculate a depression score. Participants were categorized as “yes” for depression with a PHQ-8 score ≥10, similar to the cutoff for the PHQ-9. The use of PHQ-8 depression questionnaire has been demonstrated to minimally influence overall scale performance, mean scores or diagnostic cut points as compared with use of PHQ-9 30, 31. The utility and validity of PHQ-9 depression screening and item-9 suicidal ideation assessments have been established in the present study population 32, 33

Other Covariates

Maternal age was categorized as 18–19, 20–29, 30–34, and ≥ 35 years. Educational attainment was categorized as ≤ 6, 7–12, and ≥ 12 completed years of schooling. Other socio-demographic variables were categorized as: marital status (married, living with partner vs. other), employment status (employed vs. not employed), race/ethnicity (Mestizo vs. other), difficulty accessing basic foods (hard vs. not very hard), parity (nulliparous vs. multiparous), and planned pregnancy (yes vs. no). Gestational age was based on the date of the last menstrual period and ultrasound assessment. Maternal early pregnancy body mass index (BMI; kg/m2) was categorized as <18.5, 18.5-24.9, 25-29.9, and ≥ 30 using directly measured weight and height taken at the first study visit by trained research personnel.

Statistical Analysis

Frequency distributions of maternal socio-demographic characteristics according to types of childhood abuse events were examined. Student's t-tests were used to assess differences in means of continuous variables, while Chi-Square test was used to compare percentages of categorical variables according to history of childhood abuse. Multivariate logistic regression procedures were used to calculate maximum likelihood estimates of odds ratios (ORs) at 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the presence of suicidal ideation in relation to childhood abuse (none, physical abuse only, sexual abuse only, physical and sexual abuse) and number of childhood abuse events, respectively. Potential confounders were selected a priori based on their hypothesized relationship with childhood abuse and suicidal ideation during early pregnancy. These included maternal age, maternal race/ethnicity, IPV exposure, and depression status 11, 34, 35. Because depression might modify the association between childhood abuse and suicidal ideation, analyses were repeated after stratifying the cohort according to depression status (yes vs. no). Participants with “no abuse” served as the reference group across all analyses. All reported P-values are two sided with a statistical significance set at 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). All figures were plotted using R 3.1.0 (package “ggplot2”).

Results

Selected socio-demographic data and reproductive characteristics of participants are presented in Table 1. Of the 2,964 study participants, 71.8% reported experiencing any type of childhood physical or abuse. Approximately 36.7% of participants reported experiencing intimate partner abuse in their lifetime. Further, 26.3% of participants were found to have depression (PHQ-8 score ≥ 10) and 15.8% reported suicidal ideation during early pregnancy. The mean age of participants was 28.1 years (standard deviation [SD] = 6.3 years); and the mean gestational age at interview was 9.2 weeks (SD = 3.5 weeks). The majority of participants (75.2%) identified themselves as Mestizo (mixed European and Indigenous ancestry) and 95.6% had at least 7 years of education. Characteristics of the study cohort according to childhood abuse groups are also presented in Table 1. Age, access to basics, being nulliparous, experiencing IPV, and depression were statistically significantly associated with any type childhood abuse experienced (P-value <0.05). The groups were otherwise similar for other covariates.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population according to types of childhood abuse in Lima, Peru (N = 2,964)

| Characteristics | All participants (N= 2,964) |

No abuse (N = 836) |

Physical abuse only (N = 1,146) |

Sexual abuse only (N = 231) |

Physical and sexual abuse (N = 751) |

P-value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | n | % | n | % | N | % | ||

| Age (years) a | 28.1 ± 6.3 | 27.7 ± 6.1 | 28.0 ± 6.4 | 28.2 ± 6.5 | 28.7 ± 6.3 | 0.02 | |||||

| Age (years) | 0.02 | ||||||||||

| 18-19 | 162 | 5.5 | 39 | 4.7 | 67 | 5.8 | 15 | 6.5 | 41 | 5.5 | |

| 20-29 | 1658 | 55.9 | 512 | 61.2 | 633 | 55.2 | 128 | 55.4 | 385 | 51.3 | |

| 30-34 | 609 | 20.5 | 154 | 18.4 | 236 | 20.6 | 40 | 17.3 | 179 | 23.8 | |

| ≥35 | 535 | 18.0 | 131 | 15.7 | 40 | 18.3 | 48 | 20.8 | 146 | 18.0 | |

| Education (years) | 0.68 | ||||||||||

| ≤6 | 125 | 4.2 | 37 | 4.4 | 48 | 4.2 | 5 | 2.2 | 35 | 4.7 | |

| 7-12 | 1621 | 54.7 | 467 | 55.9 | 623 | 54.4 | 123 | 53.2 | 408 | 54.3 | |

| >12 | 1211 | 40.9 | 330 | 39.5 | 473 | 41.3 | 101 | 43.7 | 307 | 40.9 | |

| Mestizo ethnicity | 2226 | 75.1 | 640 | 76.6 | 853 | 74.4 | 180 | 77.9 | 553 | 73.6 | 0.34 |

| Married/living with a partner |

2390 | 80.6 | 688 | 82.3 | 928 | 81.0 | 177 | 76.6 | 597 | 79.5 | 0.20 |

| Employed | 1367 | 46.1 | 382 | 45.7 | 516 | 45.1 | 111 | 48.1 | 358 | 47.7 | 0.65 |

| Access to basic foods | <0.0001 | ||||||||||

| Hard | 1474 | 49.7 | 350 | 41.9 | 559 | 48.8 | 126 | 54.5 | 439 | 58.5 | |

| Not very hard | 1488 | 50.2 | 486 | 58.1 | 585 | 51.0 | 105 | 45.5 | 312 | 41.5 | |

| Nulliparous | 1448 | 48.9 | 452 | 54.1 | 548 | 48.0 | 115 | 49.8 | 333 | 44.3 | 0.001 |

| Planned pregnancy | 1222 | 41.2 | 367 | 43.9 | 480 | 41.9 | 90 | 39.0 | 285 | 37.9 | 0.10 |

| Gestational age interview a | 9.2 ± 3.5 | 9.3 ± 3.4 | 9.3 ± 3.5 | 9.3 ± 3.3 | 9.2 ± 3.6 | 0.91 | |||||

| Early pregnancy body mass index (kg/m2) |

0.52 | ||||||||||

| <18.5 | 59 | 2.0 | 21 | 2.5 | 23 | 2.0 | 4 | 1.7 | 11 | 1.5 | |

| 18.5-24.9 | 1423 | 48.0 | 383 | 45.8 | 563 | 49.1 | 120 | 51.9 | 357 | 47.5 | |

| 25-29.9 | 1088 | 36.7 | 323 | 38.6 | 414 | 36.1 | 76 | 32.9 | 275 | 36.6 | |

| ≥30 | 362 | 12.2 | 93 | 11.1 | 141 | 12.3 | 26 | 11.3 | 102 | 13.6 | |

| Intimate partner violence b | 1087 | 36.7 | 203 | 24.3 | 382 | 33.3 | 99 | 42.9 | 403 | 53.7 | <0.0001 |

| Depression (PHQ-8≥10) | 781 | 26.3 | 125 | 15.0 | 338 | 29.5 | 48 | 20.8 | 270 | 36.0 | <0.0001 |

Due to missing data, percentages may not add up to 100%;

mean ± SD (standard deviation);

Lifetime intimate partner violence.

For continuous variables, P-value was calculated using the ANOVA; for categorical variables, P-value was calculated using the Chi-square test.

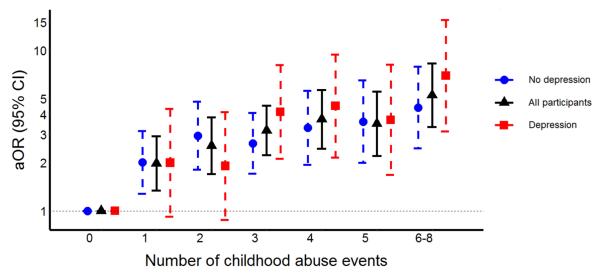

The association between history of childhood abuse and suicidal ideation during pregnancy is presented in Table 2. After adjusting for potential confounders, compared with participants reporting no history of childhood abuse, those who experienced any childhood abuse had a 3.85-fold (aOR = 3.85; 95% CI: 2.84-5.23) increased odds of reporting suicidal ideation during early pregnancy. Further adjustment for lifetime IPV and depression attenuated the magnitude of association (aOR = 2.90; 95% CI: 2.12-3.97). We next evaluated the association of specific types of childhood abuse with suicidal ideation. After adjusting for confounders including depression and lifetime IPV, compared with women who experienced no abuse during childhood, the odds of suicidal ideation was 2.30-fold for those who reported physical abuse only (aOR = 2.30; 95%CI: 1.64-3.22); 2.58-fold for those who reported sexual abuse (aOR = 2.58; 95%CI: 1.62-4.09); and 4.04-fold for those who reported experiencing both physical and sexual abuse (aOR = 4.04; 95%CI: 2.88-5.68). We next examined the association between number of childhood abuse events and suicidal ideation. There was a strong positive linear relationship between odds of suicidal ideation and the number of childhood abuse events (P-value for trend<0.001). Compared with women who experienced no abuse during childhood, those who experienced more than six childhood abuses had a 5.3-fold increased odds of (aOR=5.30; 95%CI: 3.36-8.37) suicidal ideation (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Association between childhood abuse and suicidal ideation assessed by the Patient Health Questionnaire - 9 (PHQ - 9) during pregnancy (N = 2,964).

| Childhood abuse | No suicidal ideation (N = 2,495) |

Suicidal ideation (N = 469) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) |

Adjusted OR (95% CI) a |

Adjusted OR (95% CI) b |

|

| No abuse | 786 | 31.5 | 50 | 10.7 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Any abuse | 1709 | 68.5 | 419 | 89.3 | 3.85 (2.84-5.23) | 3.85 (2.84-5.23) | 2.90 (2.12-3.97) |

| Types of abuse | |||||||

| No abuse | 786 | 31.5 | 50 | 10.7 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Physical abuse only | 971 | 38.9 | 175 | 37.3 | 2.83 (2.04-3.93) | 2.82 (2.03-3.92) | 2.30 (1.64-3.22) |

| Sexual abuse only | 191 | 7.7 | 40 | 8.5 | 3.29 (2.11-5.14) | 3.33 (2.13-5.19) | 2.58 (1.62-4.09) |

| Physical & sexual abuse | 547 | 21.9 | 204 | 43.5 | 5.86 (4.22-8.14) | 5.90 (4.25-8.20) | 4.04 (2.88-5.68) |

| Number of childhood abuse events | |||||||

| 0 | 786 | 31.5 | 50 | 10.7 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| 1 | 503 | 20.2 | 67 | 14.3 | 2.09 (1.42-3.06) | 2.11 (1.44-3.10) | 1.97 (1.34-2.92) |

| 2 | 303 | 12.1 | 61 | 13.0 | 3.15 (2.12-4.69) | 3.07 (2.06-4.56) | 2.40 (1.59-3.64) |

| 3 | 484 | 19.4 | 130 | 27.7 | 4.22 (2.98-5.95) | 4.27 (3.02-6.04) | 3.16 (2.21-4.51) |

| 4 | 186 | 7.5 | 63 | 13.4 | 5.30 (3.54-7.95) | 5.38 (3.59-8.06) | 3.69 (2.43-5.60) |

| 5 | 130 | 5.2 | 45 | 9.6 | 5.42 (3.48-8.45) | 5.38 (3.45-8.41) | 3.51 (2.21-5.56) |

| 6-8 | 103 | 4.1 | 53 | 11.3 | 8.06 (5.20-12.48) | 8.27 (5.33-12.83) | 5.30 (3.36-8.37) |

| P-value for linear trend | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval

Adjusted for maternal age (years) at interview and maternal ethnicity (Mestizo vs. other); four women had missing information on maternal ethnicity, leaving 2960 women in this analysis

Adjusted for maternal age (years) at interview, maternal ethnicity (Mestizo vs. other), lifetime intimate partner violence (no vs. yes), and depression (PHQ-8<10 vs. PHQ-8 ≥10); four women had missing information on maternal ethnicity, 10 women had missing information on the lifetime intimate partner violence, 21 women had missing information on the PHQ-8, leaving 2929 women in this analysis.

Figure 1. Association between number of childhood abuse events and suicidal ideation (SI) assessed by the Patient Health Questionnaire - 9 (PHQ - 9) during pregnancy according to depression status a.

a: All P-value for linear trend is <0.0001.

Abbreviations: aOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval

Y axis has been log transformed.

Depression is defined as Patient Health Questionnaire -8 (PHQ - 8) ≥ 10.

For all participants, we have adjusted for maternal age (years) at interview, maternal ethnicity (Mestizo vs. other), lifetime intimate partner violence (no vs. yes), and depression (PHQ-8<10 vs. PHQ-8 ≥10);

For the analyses stratified by depression status, we have adjusted for maternal age (years) at interview, maternal ethnicity (Mestizo vs. other), and lifetime intimate partner violence (no vs. yes).

The association between a history of childhood abuse and suicidal ideation was assessed after stratifying the study cohort according to the presence or absence of depression (Table 3). As can be seen in Table3, the odds of suicidal ideation was increased among women with a history of any childhood abuse irrespective of their depression status. Among women with no depression the OR for suicidal ideation was 2.73 (95% CI: 1.90-3.92); the corresponding OR among depressed women was 3.44 (95%CI: 1.84-6.43). The direction and magnitude of associations of suicidal ideation in relation to the type of abuse and the number of abuse events were also largely similar for depressed and non-depressed women (Table 3, bottom panels).

Table 3.

Association between childhood abuse and suicidal ideation assessed by the Patient Health Questionnaire - 9 (PHQ - 9) during pregnancy according to depression status (N = 2,943).

| Childhood abuse | No depression |

Depression |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No SI (N = 1,904) |

SI (N = 258) |

No SI (N = 577) |

SI (N = 204) |

|||||

| n | n | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) |

Adjusted OR (95% CI) a, b |

n | n | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) |

Adjusted OR (95% CI) a, c |

|

| No abuse | 669 | 38 | Reference | Reference | 113 | 12 | Reference | Reference |

| Any abuse | 1235 | 220 | 3.14 (2.19-4.48) | 2.73 (1.90-3.92) | 464 | 192 | 3.90 (2.10-7.23) | 3.44 (1.84-6.43) |

| Types of abuse | ||||||||

| No abuse | 669 | 38 | Reference | Reference | 113 | 12 | Reference | Reference |

| Physical abuse only | 704 | 94 | 2.35 (1.59-3.48) | 2.21 (1.49-3.28) | 261 | 77 | 2.78 (1.46-5.31) | 2.59 (1.35-4.98) |

| Sexual abuse only | 154 | 27 | 3.09 (1.83-5.21) | 2.52 (1.46-4.33) | 35 | 13 | 3.50 (1.46-8.36) | 2.96 (1.22-7.18) |

| Physical & sexual abuse | 337 | 99 | 4.62 (3.12-6.86) | 3.75 (2.50-5.63) | 168 | 102 | 5.72 (3.00-10.89) | 4.85 (2.52-9.33) |

| Number of childhood abuse events | ||||||||

| 0 | 669 | 38 | Reference | Reference | 113 | 12 | Reference | Reference |

| 1 | 406 | 47 | 2.03 (1.30-3.17) | 1.98 (1.26-3.10) | 93 | 20 | 2.01 (0.93-4.32) | 2.02 (0.93-4.38) |

| 2 | 209 | 37 | 3.11 (1.93-5.01) | 2.86 (1.75-4.68) | 93 | 20 | 2.01 (0.93-4.32) | 1.94 (0.89-4.20) |

| 3 | 343 | 61 | 3.12 (2.04-4.78) | 2.69 (1.74-4.15) | 138 | 67 | 4.56 (2.35-8.86) | 4.08 (2.09-7.99) |

| 4 | 125 | 29 | 4.07 (2.42-6.85) | 3.31 (1.94-5.62) | 61 | 34 | 5.20 (2.51-10.78) | 4.49 (2.15-9.40) |

| 5 | 82 | 22 | 4.71 (2.66-8.35) | 3.61 (2.00-6.50) | 47 | 23 | 4.57 (2.10-9.93) | 3.69 (1.67-8.12) |

| 6-8 | 70 | 24 | 6.02 (3.41-10.61) | 4.54 (2.53-8.14) | 32 | 28 | 8.17 (3.74-17.85) | 6.93 (3.12-15.39) |

| P-value for linear trend | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||

Abbreviations: SI, suicidal ideation; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval

Adjusted for maternal age (years) at interview, maternal ethnicity (Mestizo vs. other), and lifetime intimate partner violence (no vs. yes)

Two women had missing information on maternal ethnicity and seven women had missing information on the lifetime intimate partner violence, leaving 2153 women in this analysis

Two women had missing information on maternal ethnicity and three women had missing information on the lifetime intimate partner violence, leaving 776 women in this analysis.

Comment

The prevalence of childhood abuse (71.8%) and suicidal ideation (15.8%) was high in our study population. Any childhood abuse was associated with nearly three-fold increase fold (aOR = 2.90; 95% CI: 2.12-3.97) in reporting suicidal ideation during early pregnancy even with adjustment for lifetime IPV and depression. Women who experienced both physical and sexual abuse during childhood were more likely to report suicidal ideation than women experiencing only one type of abuse. The proportion of reporting suicidal ideation increased linearly with increasing number of childhood abuse events.

Our results are largely consistent with findings of other studies conducted among men and non-pregnant women. These earlier studies showed that exposure to childhood abuse is predictive of suicidal behaviors (including suicidal ideation) later in life 36-39. Results from four major reviews articles have consistently shown that adults with a history of childhood abuse are more likely to engage in suicidal behavior 36-39. However, few studies have focused on the effects of childhood abuse on suicidal ideation among pregnant women 15. In a population-based study of pregnant teens in Brazil, Coelho et al. 41 found increased odds for suicidality among teens who reported physical abuse within the 12-month period prior to interview (OR=2.36, 95% CI: 1.24-4.47) as compared with their non-abused counterparts. Our observation of increased odds of antepartum suicidal ideation with increased number of different types of childhood abuse, typically known as “poly-victimization”, is also consistent with earlier studies that have principally focused on adolescents 40, 41. Collectively our findings and those of others 40, 41 have important public health and clinical implications. Historically there has been a misconception that pregnancy might have a protective effect against suicide 42. However, an accumulating body of high quality epidemiological evidence now suggests that suicidal ideation is relatively common among pregnant women 43.

Exposure to early-life adversity such as childhood abuse has been reported to lead to persistent hyperactivity of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) circuits and sensitization of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and deficit of non-neuronal cells 44, 45. There is also emerging animal and human evidence suggesting that early-life adversity leads to epigenetic changes in genes in genes involved in the regulation of the stress-response systems 45. Of note, in studies of postmortem brain tissues of individuals who died by suicide, investigators have observed that individuals who reported childhood abuse had more DNA methylation in the glucocorticoid receptor promoter regions of their genome and reduced glucocorticoid receptor gene expression in the hippocampus than did those who did not report a history of childhood abuse 44, 46. On balance, available neurophysiological, genetic, genomic and neuroimaging studies highlight the wide range of neurobiological processes that are altered in response to experience of childhood abuse. These early mechanistic studies help to illustrate how early life stressors may disrupt the development of the central nervous system, affect brain structures, biochemistry and function in manners that may account for the diverse and enduring adverse mental health affects experienced across the life course.

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting our results. First, retrospective, self-reported childhood abuse may be subject to systematic non-disclosure, resulting in an underestimation of reported associations11. As suggested by previous longitudinal studies of adults whose childhood abuse experiences have been documented, participants’ retrospective reports of childhood abuse are likely to underestimate actual experiences47. In addition, recall bias may also result from the use of retrospective self-reported data because individuals currently experiencing psychiatric disorders were more prone to recall and disclosure prior abuse48, which could lead to an inflation of the observed association48. Future studies are warranted to develop statistical models to examine the extent and nature of misclassification in abuse reports and to develop abuse classifications taking into account misclassification in the reported data49. Second, we only used a single item asking about suicidal ideation to assess suicidality. For more precise risk assessment during pregnancy, other dimensions of suicidal behaviors (for example, suicide plan and attempt) and the context in which suicidal ideation occurs should also be examined32. Third, in our study population, the relatively high prevalence of childhood abuse and poverty may limit the generalizability of results from this high risk population to other obstetric populations. Fourth, only physical and sexual abuse during childhood were measured in our study; other types of adverse childhood events, such as childhood emotional abuse and neglect were not measured. Considering more than 70% of our participants experienced childhood physical or sexual abuse, we speculate that emotional abuse and neglect was very likely to be ubiquitous in this population. The potential impact of emotional abuse and neglect during childhood on maternal suicidal ideation should be investigated in future studies.

In summary, childhood abuse is a major global and public health problem associated with a myriad of adverse outcomes across the life course 11, 12, 50, 51. We found that a history of childhood abuse is associated with increased odds of suicidal ideation during pregnancy. Given the multiple adverse perinatal outcomes associated with childhood abuse 14, 52-55, identifying women with a history of childhood abuse and providing these women assistance to mitigate suicidal behavior is critical. Asking pregnant women during early prenatal care visits about their experience of childhood violence 56 and providing them with support during this potentially vulnerable period may help mitigate adverse psychiatric, psychosocial, perinatal and other adverse health outcomes associated with a history of childhood abuse.

Condensation.

Clinicians should be aware of the potential increased risk of suicidal behaviors among pregnant women with a history of childhood physical and sexual abuse.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by awards from the National Institutes of Health (NIH; R01-HD-059835 and T37-MD000149). The NIH had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication. The authors wish to thank the dedicated staff of Asociacion Civil Proyectos en Salud (PROESA), Peru and Instituto Nacional Materno Perinatal, Peru (INMP), for their expert technical assistance with this research. Finally, sincere gratitude is extended to all women who participated in the study as they have made invaluable personal contributions to shaping future developments in global and public health policy.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure: The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Larraín S, Bascuñán C. [Accessed Dec. 20, 2015];Child abuse: A painful reality behind closed doors. UNICEF Chile. Available at: http://www.unicef.org/lac/Boletin-Desafios9-CEPAL-UNICEF_eng.pdf.

- 2.World Health Organization . Guidelines for medico-legal care for victims of sexual violence. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andrews G, Corry J, Slade T, Issakidis C, Swanston H. Child sexual abuse. In: Ezzati M, Lopez A, Rodgers A, Murray C, editors. Comparative quantification of health risks : global and regional burden of disease atrributable to selected major risk factors. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ehlert U. Enduring psychobiological effects of childhood adversity. Psychoneuroendocrino. 2013;38:1850–7. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barrios YV, Sanchez SE, Nicolaidis C, et al. Childhood abuse and early menarche among Peruvian women. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56:197–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hornor G. Child sexual abuse: consequences and implications. J Pediatr Health Care. 2010;24:358–64. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Danese A, Moffitt TE, Harrington H, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and adult risk factors for age-related disease: depression, inflammation, and clustering of metabolic risk markers. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:1135–43. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dube SR, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Chapman DP, Williamson DF, Giles WH. Childhood abuse, household dysfunction, and the risk of attempted suicide throughout the life span: findings from the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study. JAMA. 2001;286:3089–96. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.24.3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fang X, Brown DS, Florence CS, Mercy JA. The economic burden of child maltreatment in the United States and implications for prevention. Child Abuse Negl. 2012;36:156–65. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sachs-Ericsson N, Blazer D, Plant EA, Arnow B. Childhood sexual and physical abuse and the 1-year prevalence of medical problems in the National Comorbidity Survey. Health Psychol. 2005;24:32–40. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barrios YV, Gelaye B, Zhong QY, et al. Association of childhood physical and sexual abuse with intimate partner violence, poor general health and depressive symptoms among pregnant women. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0116609. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gelaye B, Kajeepeta S, Zhong QY, et al. Childhood abuse is associated with stress-related sleep disturbance and poor sleep quality in pregnancy. Sleep Med. 2015;16:1274–80. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2015.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frankenberger DJ, Clements-Nolle K, Yang W. The Association between Adverse Childhood Experiences and Alcohol Use during Pregnancy in a Representative Sample of Adult Women. Womens Health Issues. 2015;25:688–95. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2015.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Christiaens I, Hegadoren K, Olson DM. Adverse childhood experiences are associated with spontaneous preterm birth: a case-control study. BMC Med. 2015;13:124. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0353-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Copersino ML, Jones H, Tuten M, Svikis D. Suicidal Ideation Among Drug-Dependent Treatment-Seeking Inner-City Pregnant Women. J Maint Addict. 2008;3:53–64. doi: 10.1300/J126v03n02_07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim JJ, La Porte LM, Saleh MP, et al. Suicide risk among perinatal women who report thoughts of self-harm on depression screens. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:885–93. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Czeizel AE. Attempted suicide and pregnancy. J Inj Violence Res. 2011;3:45–54. doi: 10.5249/jivr.v3i1.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gavin AR, Tabb KM, Melville JL, Guo Y, Katon W. Prevalence and correlates of suicidal ideation during pregnancy. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2011;14:239–46. doi: 10.1007/s00737-011-0207-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gandhi SG, Gilbert WM, Mcelvy SS, et al. Maternal and neonatal outcomes after attempted suicide. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:984–90. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000216000.50202.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, et al. Cross-national prevalence and risk factors for suicidal ideation, plans and attempts. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192:98–105. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.040113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organization . Millennium Development Goal 5 – improving maternal health. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oates M. Perinatal psychiatric disorders: a leading cause of maternal morbidity and mortality. Br Med Bull. 2003;67:219–29. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldg011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fuhr DC, Calvert C, Ronsmans C, et al. Contribution of suicide and injuries to pregnancy-related mortality in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1:213–25. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70282-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Department of Reproductive Health and Research. World Health Organization . Mental health aspects of women's reproductive health: A global review of the literature. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14:245–58. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Demographic and Health Surveys [Accessed Sept. 19, 2015];Demographic Health Survey questionnaires and modules: Domestic violence module. Available at : http://www.measuredhs.com/aboutsurveys/dhs/modules_archive.cfm.

- 27.Garcia-Moreno C, Jansen HA, Ellsberg M, Heise L, Watts CH. Prevalence of intimate partner violence: findings from the WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence. Lancet. 2006;368:1260–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69523-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kroenke K, Spitzer R, Williams J. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wulsin L, Somoza E, Heck J. The feasibility of using the Spanish PHQ-9 to screen for depression in primary care in Honduras. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;4:191–5. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v04n0504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Lowe B. The Patient Health Questionnaire Somatic, Anxiety, and Depressive Symptom Scales: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychistry. 2010;32:345–59. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kroenke K, Strine TW, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Berry JT, Mokdad AH. The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. J Affect Disord. 2009;114:163–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhong QY, Gelaye B, Rondon MB, et al. Using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) and the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) to assess suicidal ideation among pregnant women in Lima, Peru. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2015;18:783–92. doi: 10.1007/s00737-014-0481-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhong QY, Gelaye B, Fann JR, Sanchez SE, Williams MA. Cross-cultural validity of the Spanish version of PHQ-9 among pregnant Peruvian women: a Rasch item response theory analysis. J Affect Disord. 2014;158:148–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vigil JM, Geary DC, Byrd-Craven J. A life history assessment of early childhood sexual abuse in women. Dev Psychol. 2005;41:553–61. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.3.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gelaye B, Barrios YV, Zhong QY, et al. Association of poor subjective sleep quality with suicidal ideation among pregnant Peruvian women. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2015;37:441–7. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2015.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Santa Mina EE, Gallop RM. Childhood sexual and physical abuse and adult self-harm and suicidal behaviour: a literature review. Can J Psychiatry. 1998;43:793–800. doi: 10.1177/070674379804300803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Browne A, Finkelhor D. Impact of child sexual abuse: a review of the research. Psychol Bull. 1986;99:66–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beitchman JH, Zucker KJ, Hood JE, Dacosta GA, Akman D, Cassavia E. A review of the long-term effects of child sexual abuse. Child Abuse Negl. 1992;16:101–18. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(92)90011-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller AB, Esposito-Smythers C, Weismoore JT, Renshaw KD. The relation between child maltreatment and adolescent suicidal behavior: a systematic review and critical examination of the literature. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2013;16:146–72. doi: 10.1007/s10567-013-0131-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Finkelhor D, Ormrod RK, Turner HA. Poly-victimization: a neglected component in child victimization. Child Abuse Negl. 2007;31:7–26. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Finkelhor D, Ormrod RK, Turner HA. Lifetime assessment of poly-victimization in a national sample of children and youth. Child Abuse Negl. 2009;33:403–11. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Appleby L. Suicide during pregnancy and in the first postnatal year. BMJ. 1991;302:137–40. doi: 10.1136/bmj.302.6769.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Newport DJ, Levey LC, Pennell PB, Ragan K, Stowe ZN. Suicidal ideation in pregnancy: Assessment and clinical implications. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2007;10:181–7. doi: 10.1007/s00737-007-0192-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Turecki G, Ernst C, Jollant F, Labonte B, Mechawar N. The neurodevelopmental origins of suicidal behavior. Trends Neurosci. 2012;35:14–23. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2011.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Van Heeringen K, Mann JJ. The neurobiology of suicide. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1:63–72. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70220-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Labonte B, Yerko V, Gross J, et al. Differential glucocorticoid receptor exon 1(B), 1(C), and 1(H) expression and methylation in suicide completers with a history of childhood abuse. Biol psychiatry. 2012;72:41–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Della Femina D, Yeager CA, Lewis DO. Child abuse: Adolescent records vs. adult recall. Child Abuse Negl. 1990;14:227–31. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(90)90033-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nelson EC, Heath AC, Madden PA, et al. Association between self-reported childhood sexual abuse and adverse psychosocial outcomes: results from a twin study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:139–45. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.2.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fergusson DM, Boden JM, Horwood LJ. Exposure to childhood sexual and physical abuse and adjustment in early adulthood. Child Abuse Negl. 2008;32:607–19. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lindert J, Von Ehrenstein OS, Grashow R, Gal G, Braehler E, Weisskopf MG. Sexual and physical abuse in childhood is associated with depression and anxiety over the life course: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Public Health. 2014;59:359–72. doi: 10.1007/s00038-013-0519-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stein DJ, Scott K, Haro Abad JM, et al. Early childhood adversity and later hypertension: data from the World Mental Health Survey. Ann Clin Psychiatry: 2010;22:19–28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Drevin J, Stern J, Annerback EM, et al. Adverse childhood experiences influence development of pain during pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2015;94:840–6. doi: 10.1111/aogs.12674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wosu AC, Gelaye B, Williams MA. Maternal history of childhood sexual abuse and preterm birth: an epidemiologic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:174. doi: 10.1186/s12884-015-0606-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wosu AC, Gelaye B, Williams MA. History of childhood sexual abuse and risk of prenatal and postpartum depression or depressive symptoms: an epidemiologic review. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2015;18:659–71. doi: 10.1007/s00737-015-0533-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wosu AC, Gelaye B, Williams MA. Childhood sexual abuse and posttraumatic stress disorder among pregnant and postpartum women: review of the literature. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2015;18:61–72. doi: 10.1007/s00737-014-0482-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.O'campo P, Kirst M, Tsamis C, Chambers C, Ahmad F. Implementing successful intimate partner violence screening programs in health care settings: evidence generated from a realist-informed systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72:855–66. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]