Abstract

Two major problems with implanted catheters are clotting and infection. Nitric oxide (NO) is an endogenous vasodilator as well as natural inhibitor of platelet adhesion/activation and an antimicrobial agent, and NO-releasing polymers are expected to have similar properties. Here, NO-releasing central venous catheters (CVCs) are fabricated using Elast-eon™ E2As polymer with both diazeniumdiolated dibutylhexanediamine (DBHD/NONO) and poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) additives, where the NO release can be modulated and optimized via the hydrolysis rate of the PLGA. It is observed that using a 10 % w/w additive of a PLGA with ester end group provides the most controlled NO release from the CVCs over a 14 d period. The optimized DBHD/NONO based catheters are non-hemolytic (hemolytic index of 0%) and noncytotoxic (grade 0). After 9 d of catheter implantation in the jugular veins of rabbits, the NO-releasing CVCs have a significantly reduced thrombus area (7 times smaller) and a 95% reduction in bacterial adhesion. These results show the promise of DBHD/NONO-based NO releasing materials as a solution to achieve extended NO release for longer term prevention of clotting and infection associated with intravascular catheters.

Keywords: Antibacterial, Hemocompatibility, Catheters, Nitric Oxide, Poly (lactide-co-glycolide)

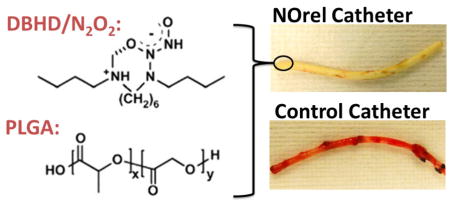

Graphical Abstract

Diazeniumdiolated dibutylhexanediamine (DBHD/N2O2) based nitric oxide (NO) releasing catheters were fabricated and optimized using PLGA additive for sustained NO release for 14 d period. These nonhemolytic and noncytotoxic NO-releasing (NOrel) catheters were able to significantly reduce clotting and bacterial infection in a long-term rabbit model.

1. Introduction

Infection and thrombus formation are the leading complications for blood-contacting devices in clinical settings today, and can result in extended hospital stays, increased healthcare costs, and even patient death [1, 2]. Thrombus formation is currently treated through the systemic administration of heparin, increasing the risk for hemorrhage, thrombocytopenia, and thrombosis in patients [3]. Even with the use of heparin, venous thrombosis has been detected via Doppler imaging in 33% of intensive care unit patients [4]. Intravascular catheters are used in a variety of different settings, and range greatly in the length of use. Acute catheters used in operating rooms, emergency rooms, and intensive care units (ICUs) are typically used for up to 7 days, while more permanent catheters for cases such as long-term nutrition or dialysis can be used from months to years [2]. Preventing thrombus formation over these time periods is critical to maintain the functionality of the catheter. Long-term systemic administration of anticoagulants increase the patients risk for the complications stated above. Local administration of the anticoagulant, such as heparin lock solutions, are currently used clinically to prevent this local thrombus formation, but fail to address issues related to microbial infection [5].

Catheter associated infections are prevalent in clinical settings, where 1.7 million healthcare associated infections result in 99,000 deaths per year in the United States alone [6]. Infections associated with indwelling catheters are particularly common, where up to 40% of all indwelling catheters become infected [7]. The majority of serious catheter-related infections are associated with central venous catheters (CVCs), where more than 250,000 CVC-associated infections occur annually in the United States which results in $25,000 additional costs and a mortality rate of 12–25% per infection[8, 9]. The treatment of these infections is typically done through the use of antibiotics, and has led to the development of antibiotic resistant strains of bacteria, such as methicillin resistant Staphyloccus aureus (MRSA) and Acinetobacter baumannii [10, 11]. Once adhered to a surface, bacteria also have the ability to form biofilms, where an extracellular carbohydrate matrix encases communities of bacteria to protect the bacteria from bactericidal and bacteriostatic agents. This biofilm formation makes it difficult for antibiotics to penetrate, and has been shown to require up to 1000 times higher dose [12]. Bacteria that have adhered to a intravascular catheter can also detach from the surface and lead to bloodstream infections (80,000/year) and possibly death (28,000/year) [8].

The ability of bacteria or proteins (e.g., fibrinogen and von Willebrand Factor that stimulates activation of platelets to cause clotting) to adhere to the surface of catheter materials is influenced by a number of characteristics, including surface roughness and surface charge (hydrophobicity). Many approaches have been used to increase the biocompatibility of materials through limiting protein adsorption by decreasing surface roughness, varying hydrophobicity, zwitterionic surfaces, or grafting of hydrophilic polymers such as poly-ethelyne glycol [13–19]. While these approaches can aid in limiting protein adsorption and bacteria adhesion, they do not address complications associated with platelet activation and adhesion, or respond to any bacteria that have adhered to the surface. Polymers with heparin immobilized to their surface, have been shown to be effective at reducing thrombosis, and have reached the marketplace and clinical use [20–24]. However, these products still lack an active approach to prevent infection. Active catheter coatings containing antibacterial agents such as silver or antibiotics are available, but have nearly the same rate of infection as standard catheters [25]. In addition, both the silver and antibiotic containing catheters also do not address issues associated with platelet activation.

An alternative approach to improving the biocompatibility of materials is to mimic the natural endothelium. It has been shown that nitric oxide (NO) is the primary regulator in inhibiting platelet activation and adhesion, and is naturally released form vasculature at an estimated surface flux of 0.5 – 4 ×10−10 mol cm−2 min−1 [26, 27]. Along with inhibiting platelet adhesion, NO has also been shown to have broad-spectrum antimicrobial properties, killing both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria [28–32]. Many NO donors such as S-nitrosothiols [33, 34] and N-diazeniumdiolates [35, 36] have been developed and studied for their potential to locally release NO from polymer surfaces. The addition of NO donors into polymeric materials has been shown to be non-cytotoxic and non-hemolytic, while maintaining the mechanical properties of the base polymer [37].

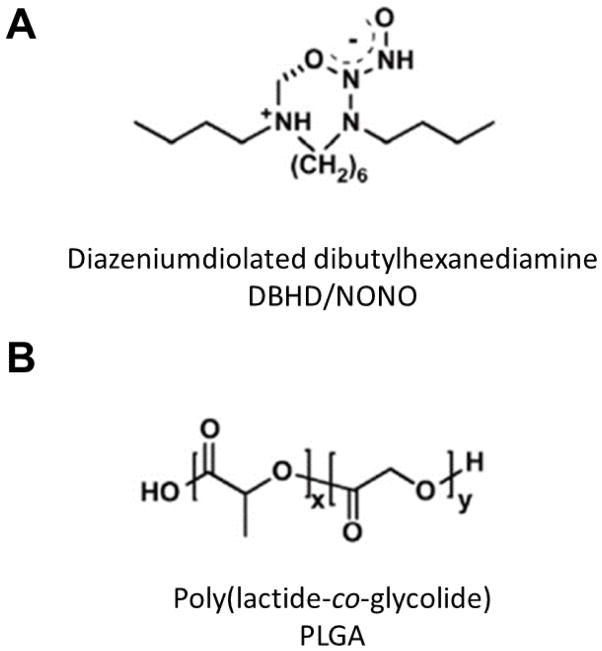

A major requirement for long-term applications is the ability extend the NO release lifetime to match the intended usage lifetime of the biomedical device. Methods for controlling the release of NO from materials have been the applications of additional polymer top coats in order to prevent leaching of the NO donor molecules, the use of polymers with low water uptake, as well as chemical additives. Prior work has shown diazeniumdiolated dibutylhexanediamine (DBHD/NONO) (Figure 1.A.) releases physiological levels of NO when incorporated into hydrophobic polymer films [38–41]. However, the proton driven release mechanism of NO from this molecule creates free lipophilic amine species, increasing the pH within the material which stops the NO release before the total available NO was released [42]. Initially Batchelor et al utilized lipophilic anionic species (e.g., tetraphenyborate derivatives) as additives that slightly extended the NO release from films by buffering the proton activity within the polymer [38, 42]; however, there were concerns related to its cytoxicity towards endothelial and smooth muscle cells [43]. The addition of poly(lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) has been one of the most promising methods reported to date of extending NO release from diazeniumdiolate-based materials. The NO release from DBHD/NONO-based materials can be modulated using PLGA additives, which hydrolyzes to produce lactic/glycolic acid species that can balance the production of the lipophilic DBHD amine byproduct of the NO release reaction and continue to promote NO release (Fig. 1. B.) [40, 41, 44]. The specific properties (i.e., acid or ester end groups) of the PLGA additives were previously studied in terms of their initial NO burst release effects, where PLGAs with acid end groups were found to produce an unwanted burst release from DBHD/NONO [40, 41]. In these prior studies films prepared with PLGAs with ester end groups avoided this burst release and had extended NO release profiles.

Figure 1.

Strucute of (A) diazeniumdiolated dibutylhexanediamine and (B) poly(lactide-co-glycolide).

Herein, we report the use of PLGA and DBHD/NONO as additives with in Elast-eon E2As polyurethane to fabricate NO-releasing central venous catheters (CVCs) in order to combat issues of both thrombosis and infection. The release rates of NO were measured from the formulations utilizing PLGAs with ester end groups in order to avoid any burst release and optimize the NO release profile over a 14 day period. The optimized NO-releasing CVCs were evaluated in long-term (9 d catheter) intravascular rabbit studies to observe the NO effects on prevention of clotting and bacterial adhesion, in comparison to E2As control catheters.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Anhydrous tetrahydrofuran (THF), anhydrous acetonitrile, sodium chloride, potassium chloride, sodium phosphate dibasic, and potassium phosphate monobasic were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Company (St. Louis, MO). Poly(D,L-lactide-co-glycolide) materials with ester end groups (product numbers 50:50-DLG-7E and 65:35-DLG-7E) were obtained from SurModics Pharmaceuticals Inc. (Birmingham, AL). N,N′-Dibutyl-1,6-hexanediamine (DBHD) was purchased from Alfa Aesar (Ward Hill, MA). DBHD/NONO was synthesized by treating DBHD with 80 psi NO gas purchased from Cryogenic Gases (Detroit, MI) at room temperature for 48 h, as previously described [45]. Elast-eon™ E2As was obtained from AorTech International, plc (Scoresby, Victoria, Australia).

2.2. Preparation of NO-releasing Central Venous Catheters

Catheters were prepared by dip coating polymer solutions on 18 cm long stainless steel mandrels of 1.2 mm diameter (purchased from McMaster Carr). Catheters were prepared using a slightly modified method as previously described [2]. For NO release measurements, small sections of catheters were made with the various PLGAs, and at various concentrations, to determine the optimum formulation for in vivo studies.

Control CVCs

The polymer solution consisted of E2As dissolved in THF (150 mg/mL). Thirty-five coats of the E2As solution was applied on the mandrel by dip coating.

NO-releasing CVCs

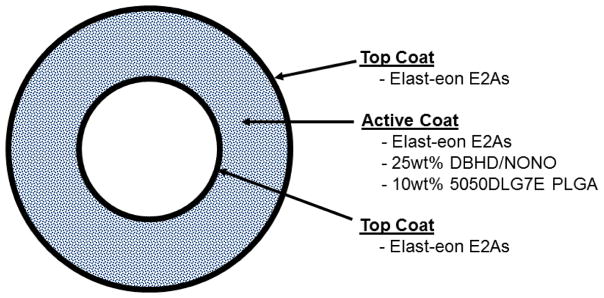

Two different solutions, namely top/base coat and active, were prepared to make the trilayer catheters (Figure 2). The top/base coat solution consisted of E2As dissolved in THF (150mg/mL). The active solution was made up of 25 weight% DBHD/NONO with various corresponding ratios of PLGA and E2As (e.g., 10 weight% PLGA and 65 weight% E2As) dissolved in THF with overall concentration of 150 mg/mL. Trilayer catheters were prepared by dip coating 5 base coats of E2As solution, 25 coats of active solution, and 5 top coats of E2As solution.

Figure 2.

Cross sectional view of DBHD/NONO-PLGA catheters. Various weight% of PLGA, as well as PLGAs with various degradation rates, were fabricated in a similar fashion.

All catheters were allowed to dry overnight under ambient conditions. Cured catheters were removed from the mandrels and dried under vacuum for additional 48 h. Catheters had an i.d. of 1.20 ± 0.07 mm and o.d. of 2.20 ± 0.11 mm, as measured with a Mitutoyo digital micrometer.

2.3. Nitric Oxide Release Measurements

A Sievers chemiluminescence Nitric Oxide Analyzer (NOA), model 280 (Boulder, CO) was used to measure the real-time release of NO from the catheters in vitro. A small sample of a catheter (1 cm in length) was placed in 4 mL PBS buffer at 37 °C, where nitrogen gas is bubbled into the PBS buffer to free NO from solution and a sweep gas of nitrogen carries the NO rich gas to the chemiluminescence detection chamber. Catheters were incubated in 4 mL of PBS buffer at 37 °C between measurements, where the incubating buffer was replaced daily. After the 9 d chronic rabbit study, a section of the catheter was tested for NO release post-blood exposure.

2.4 Cytotoxicity Study Using the ISO Elution Method

The cytotoxicity of the 25 weight% DBHD/NONO + 10 weight% 50:50 PLGA catheters was determined using ISO 10993-5 Elution Method by NAMSA®. Leachable extracted from the 25 weight% DBHD/NONO catheters was introduced to mammalian cells to determine if there were any toxic effects. A single preparation of the 25 weight% DBHD/NONO catheter was extracted into single strength Minimum Essential Medium (1X MEM) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum, 2% antibiotics (100 units/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin and 2.5 μg/mL amphotericin B) and 1% (2 mM) L-glutamine (1X MEM) at 37 °C for 24 hours. Negative and positive controls (high density polyethylene (HDPE) and powder-free latex gloves respectively), and reagent control (1X MEM) were similarly prepared using MEM medium. The 25 weight% DBHD/NONO catheters were prepared as described in Section 2.2 and returned to the freezer until testing. The extracts were continuously agitated during extraction, and not centrifuged, filtered, or otherwise altered prior to dosing. The 1X MEM extraction was performed using serum to optimize extraction of both polar and non-polar components. Mouse fibroblast cells (L-929) were propagated and maintained in flasks containing 1X MEM at 37 °C with 5% carbon dioxide (CO2), and seeded in 10 cm2 cell culture wells and incubated at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2 to obtain subconfluent monolayers of cells. Subconfluent cell monolayers were then used for leachate exposure and performed in triplicate. The growth medium contained in the triplicate cultures was replaced with 2.0 mL of the test extract, reagent control, negative control, or positive control extract depending on the experiment and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 48 hours. The color of the test medium was observed to determine any change in pH, where a color shift toward yellow indicates an acidic pH range, and a color shift toward purple indicates an alkaline pH range.

2.5 Hemolysis Testing

The hemolytic activity of 25 weight% DBHD/NONO + 10 weight% 50:50 PLGA catheters was measured in vitro using ASTM F756, Standard Practice for Assessment of Hemolytic Properties of Materials and ISO 10993-4 by NAMSA®. Whole blood from 4 New Zealand White rabbits was collected into 7 mL vacuum tubes containing 12 mg ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) as the anticoagulant. The drawn blood was maintained at room temperature and used within four hours of collection. Anticoagulated whole rabbit blood was pooled, diluted, and added to tubes with the test sample in calcium and magnesium-free phosphate buffered saline (CMF-PBS). The pooled blood was diluted with CMF-PBS to a total hemoglobin concentration of 10 ± 1.0 mg/mL. In a ratio of 1.0 mL diluted blood to 7.0 mL CMF-PBS, samples were prepared in triplicate both for direct contact as well as extraction. The samples were capped, inverted gently to mix the contents, and then maintained for at least 3 h at 37°C with periodic inversions at approximately 30-min intervals. Following incubation, the blood-CMF-PBS mixtures were transferred to separate disposable centrifuge tubes. These tubes were centrifuged for 15 min at 700–800 x g. Negative controls (HDPE), positive controls (sterile water for injection), and blanks (CMF-PBS) were prepared in the same manner. The condition of the supernatant was recorded and a 1.0 mL aliquot was added to individual 1.0 mL portions of Drabkin’s reagent (hemoglobin reagent) and allowed to stand for 15 min at room temperature for all samples (DBHD/NONO, negative control, positive control, and blank). The conditions of the test article supernatants were recorded a second time. The absorbance of each test article, negative control, positive control, and blank solution was measured at 540 nm using a spectrophotometer. The condition of the test article supernatants was then recorded a third, and the final time.

The hemoglobin concentration for each test was then calculated from the standard curve. The blank corrected percent hemolysis was calculated for 25 weight% DBHD/NONO and the negative and positive controls as follows (where ABS = absorbance):

For the sample to be considered valid, negative controls must have had a blank corrected % hemolysis value <2%, while positive control must have had a blank corrected % hemolysis value of >5%. If either of these values were not within the acceptable range, the test was repeated with fresh blood.

The mean blank corrected % hemolysis (BCH) was calculated by averaging the blank corrected % hemolysis values of the triplicate test samples. In the event the BCH resulted in a value less than zero, the value was reported as 0.00. The standard deviation for the replicates was determined. An average hemolytic index of the triplicate test samples was also calculated as follows:

2.6. Long-term Catheter Implantation in Rabbit Model

Rabbit catheter implantation protocol

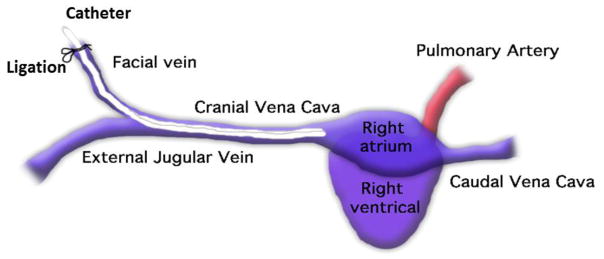

All animals were cared for by the standards of the University Committee on Use and Care of Animals (UCUCA) at the University of Michigan. The surgical area was sanitized and dedicated to the purpose of performing surgery. All surgical instruments were sterilized using steam sterilization and sterile drapes were used to create a sterile field around the dorsal and ventral sides of rabbit neck. A total of 6 New Zealand white rabbits (Myrtle’s Rabbitry, Thompson’s Station, TN) were used in this study. All rabbits (2.5–3.5 kg) were initially anesthetized with intramuscular injections of 5 mg/kg xylazine injectable (AnaSed® Lloyd Laboratories Shenandoah, Iowa) and 30 mg/kg ketamine hydrochloride (Hospira, Inc. Lake Forest, IL). Maintenance anesthesia was administered via isoflurane gas inhalation at a rate of 1.5–3% via mechanical ventilation which was done via a tracheotomy and using an A.D.S. 2000 Ventilator (Engler Engineering Corp. Hialeah, FL). Rabbit neck area was cleaned with iodine and ethanol prior to incision. A modified rabbit venous model, originally developed by Klement et al, was used where the facial vein was used as an access point to the external jugular vein and the tip of the catheter was placed at the entrance to the right atrium [46]. By using the facial vein, the external jugular vein blood flow was maintained over the catheter which provided both thrombosis and biofilm assessments. Under sterile conditions, a small skin incision (2 cm) was made over the right external jugular vein and the internal jugular vein branch isolated for the catheter insertion. Briefly, the internal jugular vein was ligated proximally and under distal occlusion, a small venotomy was made through which the catheter was introduced into the jugular vein through the facial vein and then advanced into the cranial vena cava, as shown in Figure 3. About 7 cm of a catheter length was inserted and then fixed to the vein at its entrance by two sterile silk sutures. A second skin incision (1 cm) was made on the dorsum of the neck. The remaining external portion (8 cm in length) of the catheter was then tunneled under the skin from the jugular vein entrance and was exteriorized through the dorsal skin incision. Skin incisions were closed in a routine manner using uninterrupted stitches (absorbable suture) for the ventral incision and interrupted stitches (absorbable suture) for the dorsal incision. The open end of the catheter was closed by a subcutaneous vascular access port. Thereafter, the incision sites were treated with Neosporin ointment. Animals were given prophylactically Enrofloxacin (5 mg/kg SC daily for 4 days) as a broad-spectrum antibiotic postoperatively. After removal from anesthesia, animals were placed in an oxygenated and 37 °C incubator for post-operative recovery. Animals were checked during 1–2 h recovery until they were able to maintain sternal recumbency before moving to the animal facility.

Figure 3.

Schematic showing placement of catheter in rabbit jugular vein.

Post-operative recovery protocol

The rabbits that recovered from anesthesia after the catheter placements were housed individually with a respective cage card identifying the animal in the animal facility. Animal health was monitored during routine daily check-ups and weighing, the implanted venous catheters exit site and the skin incision was examined for inflammation (redness). Four mg/kg Rimadyl (analgesic) was given for 2 days after surgery and 5mg/kg Baytril (antibiotic) was given for 4 days post-surgery. The catheter was flushed with 2 mL of sterile saline every day. After 9 d, rabbits were given 400 IU/kg sodium heparin just prior to euthanasia to prevent necrotic thrombosis. The animals were euthanized using a dose of Fatal Plus (130 mg/kg sodium pentobarbital) (Vortech Pharmaceuticals Dearborn, MI).

Catheter evaluation

After explanting, the catheters were rinsed in PBS. Pictures were taken of the exterior of the whole catheter and the interior of a 1 cm piece cut longitudinally using a Nikon L24 digital camera. Starting at the distal tip of the catheter, 1 cm sections were cut for SEM, bacterial adhesion, and NO release testing. To quantitate the viable bacteria, a 1 cm piece was cut longitudinally and was placed in 1 mL PBS buffer. Bacteria were detached from the catheter by vigorous shaking using a OMNI TH homogenizer (Kennesaw, GA), to provide a uniform bacterial suspension. The resulting homogenate was serially diluted in sterile PBS. The optimal homogenizing speed was found using a separate experiment where different homogenizing speeds and times were compared to provide the highest viable bacteria count. Triplicate aliquots of each dilution (10μL) of each dilution were plated on agar plates. The agar plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 h followed by calculation of colony forming units per catheter surface area (CFU/cm2).

2.7. Scanning Electron Microscopy

After explantation from rabbit veins, 1 cm catheter pieces were immersed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde solution for 2 h followed by 3 washes with phosphate buffer. Catheter pieces were treated with 1% Osmium tetroxide in 0.1M Cacodylate, pH 7.4 for 1 hour followed by 3 washes with phosphate buffer. The catheter samples were dehydrated in ascending series of ethyl alcohols (30%–100%), mounted on SEM stubs, and subsequently sputtered with gold. The specimens were examined in a scanning electron microscope AMRAY FE 1900 (FEI Company, Philips, Eindhoven, Netherlands) operating at 20 kV.

2.8 Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (standard error of the mean). Comparisons between the control and NO-releasing CVCs were conducted using a two tailed Student’s t-test, where p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all tests.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1 In vitro NO release from Central Venous Catheters containing DBHD/NONO in E2As with various PLGA additives

The Elast-eon™ E2As polyurethane has been shown previously to have excellent intrinsic biocompatibility and stability properties, exhibiting low levels of blood protein adhesion, and providing excellent biocompatibility when combined with NO releasing materials in vivo [39, 47–49]. In a rabbit model of extracorporeal circulation, Elast-eon E2As was found to have significantly better intrinsic hemocompabitility properties that other common polymers (e.g., PVC/DOS), in terms of platelet preservation and thrombus formation [39, 40]. We have previously demonstrated that acid capped PLGA gives an initial burst of NO on day 1 which quickly depletes the NO reservoir, and ultimately limits the NO release to 1 week above physiological levels [40]. In this study, two PLGA additives with ester end groups were used as a proton donor source for the DBHD/NONO-based central venous catheters in order to modulate the NO release profile and maintain a better balance between the DBHD amine production rate (the byproduct of the NO release mechanism) and acid monomer production from PLGA hydrolysis, thereby prolonging the release for a 2 week period. PLGA hydrolysis is initiated in the presence of water, where the ester bonds in PLGA hydrolyze to yield lactic and glycolic acids, which enables control of the pH within the polymer matrix [40, 41, 50].

The NO-releasing CVCs used in this study had middle NO-releasing layer that was topcoated with the E2As base polymer, as described in Section 2.2 (Figure 2). The NO-releasing layer consisted of E2As with 25 weight% DBHD/NONO and 5, 10, or 25 weight% PLGA additives. Twenty-five weight% DBHD/NONO has been found to be optimum in terms of providing sufficient NO for extended release lifetimes [39, 40, 44]. The E2As top coat is used to prevent/reduce leaching of DBHD/NONO, neutralize the surface charge, and yield a smoother finish to the surface [40]. In this study, PLGA additives with ester end groups, an approximate inherent viscosity of 0.7 dL/g, and either a 50:50 or 65:35 acid monomer ratio were compared. PLGAs with a 50:50 lactide to glycolide monomer ratio have faster hydrolysis, and increasing the lactide amount will decrease the PLGA hydrolysis rate. All the NO-releasing CVCs were tested and incubated at 37 °C in PBS buffer, which was changed every day, in order to mimic physiological conditions throughout the NO release testing.

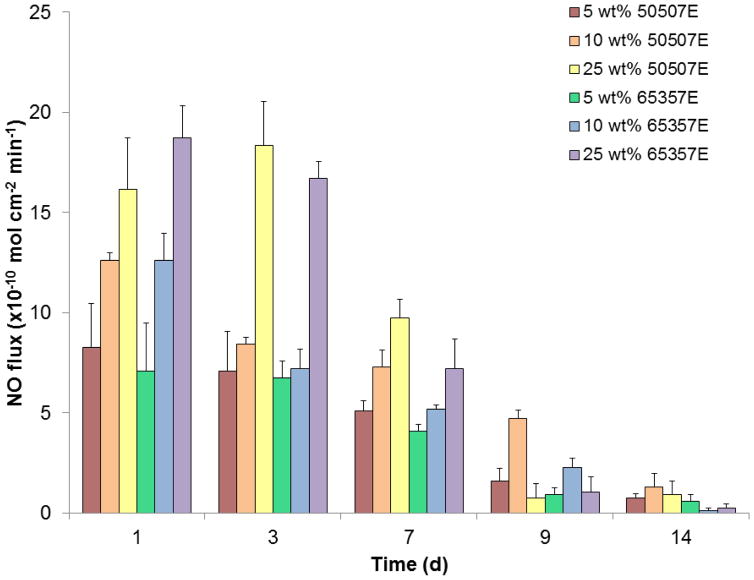

The NO release was tested over a 2 week period for CVCs prepared with 25 weight% DBHD/NONO with 5, 10, and 25 weight% of 50:50 or 65:35 PLGA additives in E2As polyurethane (Figure 4). Catheters with 5 weight% 50:50 and 65:35 catheters release NO for 14 d; however, on the later days of testing the NO surface fluxes were quite low. These lower NO release levels indicate that the 5 weight% PLGA is not adequate to compensate for the pH increase due to production of free DBHD amines within the polymer. Increasing the PLGA additive to 25 weight% yield catheters that exhibit high fluxes on days 1–3 due to the increased amount of acid monomers being produced, resulting in complete depletion of the NO reservoir by day 14 with lower fluxes (<1×10−10 mol cm−2 min−1) on days 9–14. No significant difference between the NO release levels observed from catheters containing the same weight% of either 50:50 and 65:35 PLGA additives was observed. This similarity can be attributed to the fact that we only test the catheters for the initial 2-week period, whereas these PLGAs have much longer hydrolysis timeframes. In addition, these PLGAs are being doped into a hydrophobic polymer (with water uptake < 8%), which likely slows the hydrolysis rates even further [51]. Overall, the catheters prepared with 10 wt% of the 50:50 PLGA additive had the most consistent NO flux with no initial burst of NO, and this enabled the NO release to be prolonged for up to 14 d period with NO flux ~ 4 x 10−10 mol cm−2 min−1 on day 9. The NO release testing was discontinued after the NO flux dropped below physiological levels (< 0.5 x10−10 mol cm−2 min−1). During this 14 day period, the NO released from this catheter formulation accounts for approximately 56% of the theoretical NO based on the NO release profiles. The remainder of the theoretical NO loading with the catheter was either released during the catheter preparation or still remains within the catheter material. During the catheter preparation and curing the PLGA residual acid monomers can react and release NO at room temperature. In addition, some DBHD/NONO may still be present within the catheter because the low water uptake of the E2As polymer may also reduce the diffusion of water throughout the entire catheter wall which may subsequently limit the PLGA hydrolysis and NO release from the DBHD/NONO molecules within the center catheter layer. Despite these limitations, physiological NO release is achieved from the catheters with 10 wt% 50507E PLGA for up to 14 days; therefore, this formulation was used for subsequent long-term catheter evaluations in the rabbit model.

Figure 4.

Nitric oxide release measurements as measure via chemiluminescence under physiological conditions (in PBS at 37 °C) for various DBHD/NONO-PLGA catheter formulations (n=3 for each).

3.2 Cytotoxicty and Hemolysis analysis of DBHD/NONO doped E2As

Cytotoxicity

Treating cells with a chemical agent can result in a variety of cell fates such as altered metabolism, decrease in cell viability, necrosis death, and change in the genetic program of cells ultimately resulting in apoptosis (programed cell death). L-929 mouse fibroblast cells were examined microscopically (100X) after incubation with the 25 weight% DBHD/NONO + 10 weight% 50:50 PLGA catheters using ISO 10993-5 elution method. Abnormal morphology and cellular degeneration, as well as percent lysis were recorded. For the test to be valid, the reagent control and the negative control must have had a reactivity of none (grade 0) and the positive control must have moderate (grade 3) or severe (grade 4) reactivity. In the event of 100% cell lysis, percent rounding and percent cells without intracytoplasmic granules were not evaluated. The reagent control (1X MEM), negative control (HDPE), and the positive control (powder-free latex glove) performed as anticipated (grade 0, grade 0, and grade 4 respectively). The 25 weight% DBHD/NONO catheters showed no evidence of causing cell lysis or toxicity when tested for 48 h on L-929 mouse fibroblast cells (grade 0), where the positive control showed 100% cell death.

Hemolysis

Hemolysis testing is considered to be the most common method to evaluate the hemolytic properties of any blood contacting biomaterial or device. The test is based on erythrocyte (red blood cells) lysis induced by contact, toxins, metal ions, leachables, and surface charge or any other cause of red blood cells lysis. The hemolytic potential of the NO-releasing catheters was tested in vitro for 3 h at 37 °C on blood samples sourced from rabbit using ISO 10993-4 protocol. In the event the hemolytic index resulted in a value less than zero, the value was reported as 0.0. The hemolytic index for 25 weight% DBHD/NONO catheters in direct contact with blood was 0.0 ± 0.1% when compared to negative and positive controls (BCH 0.0 ± 0.1%, 102 ± 1.7% respectively). Extract from the catheters was also tested, where and the hemolytic index for 25 weight% DBHD/NONO catheters was 0.05 ± 0.1%, with negative and positive controls of 0.23 ± 0.1% and 99.77 ± 2.3%, respectively. Thus, catheters containing 25 weight% DBHD/NONO in direct contact with blood and the sample extract were found to be non-hemolytic in a 3 h study.

3.3. Evaluation of thrombus formation and bacterial adhesion on E2As NO-releasing CVCs in 9 d rabbit model

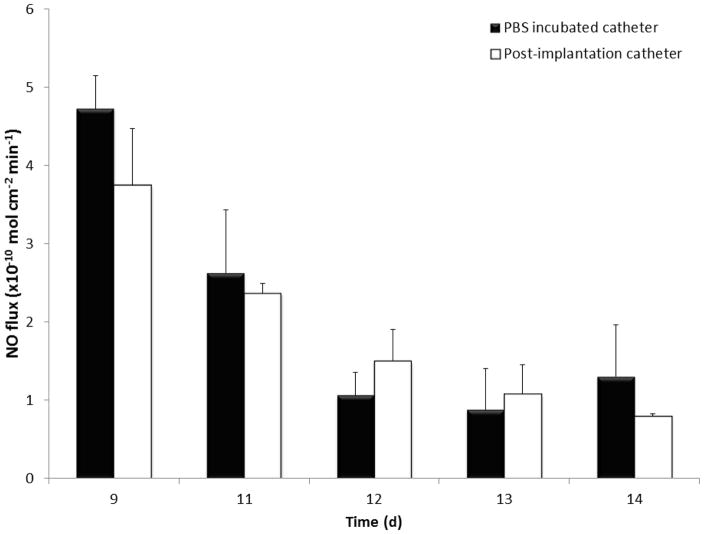

Central venous catheters were prepared using a dip coating method as described in Section 2.2. The NO-releasing and control CVCs were implanted for 9 days in rabbits in cranial vena cava, as shown in Figure 3 (1 catheter per rabbit) for evaluation of their hemocompatiblity. All the rabbits recovered rapidly from surgical procedure, with only mild weight loss observed after 1–2 days post-surgery, but returned to baseline in subsequent days with normal activity level. Post-implanted catheters had a NO flux of 3.8 ± 0.7 x 10−10 mol cm−2 min−1 on the day of explantation, which is well within the normal range of NO from the endothelium [27]. Post-implanted catheters continued to release NO for 5 d after explantation and the flux levels were found to be similar to the catheters that had been continuously incubated in PBS at 37°C (see Figure 5). This data is consistent with our previous short-term animal data where we have shown that NO release is not compromised due to blood exposure [38, 40].

Figure 5.

Nitric oxide release measurements from PBS incubated and explanted DBHD/NONO-PLGA catheters.

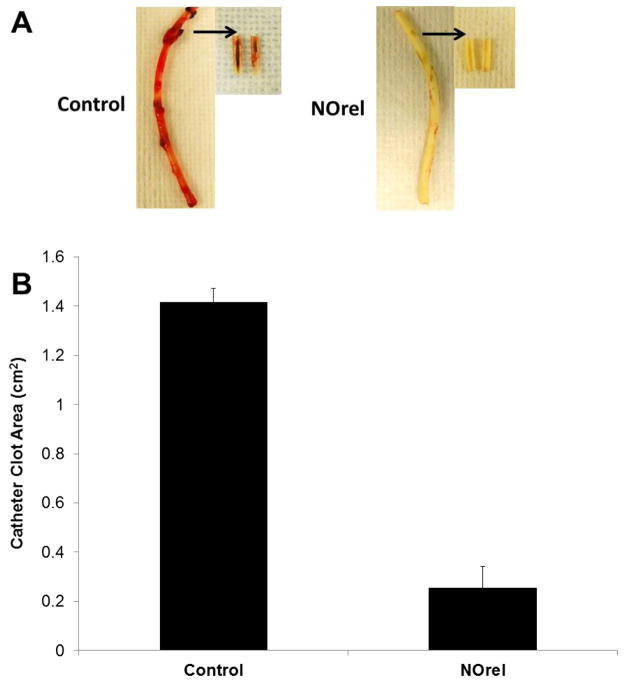

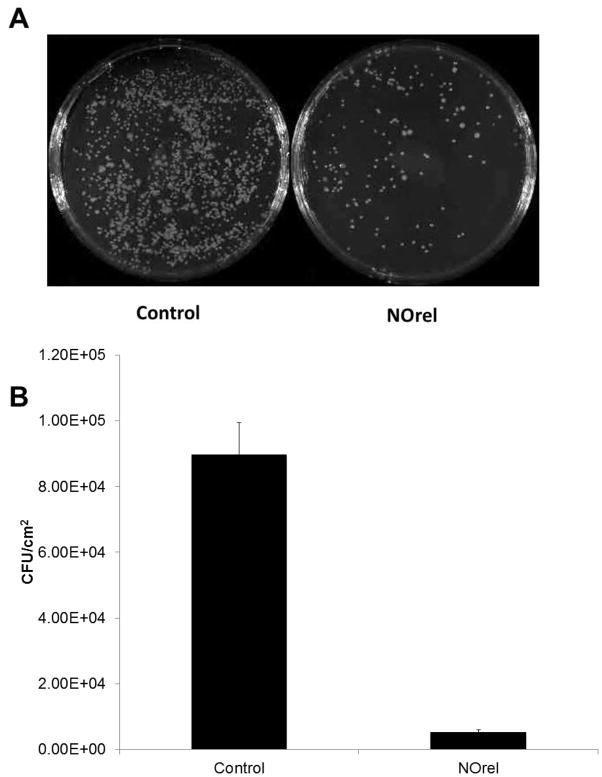

Surface thrombi on the explanted catheters were photographed and the degree of thrombus area was quantitated using ImageJ imaging software from National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD). The NO-releasing CVCs had significantly less clot formation (Figure 6A), where the inset pictures show representative images of the clot formation on the interior walls of the catheter. These thrombi area measurements were quantitated and, as shown in Fig. 6B, the thrombus area of the NO-releasing catheters was significantly lower compared to the control catheters (0.25 ± 0.08 and 1.40 ± 0.05 cm2, respectively). One cm catheter sections were homogenized in 1mL PBS to detach the bacteria from the inner and outer surfaces and cultured as described in experimental section above [51]. The bacterial colonies were counted the following day and were represented as CFU/cm2 in Figure 7A. A 95% reduction in bacterial adhesion was observed for NO-releasing catheters as compared to the controls (Figure 7B).

Figure 6.

(A) Representative images of control and NO-releasing (NOrel) catheters after explantation. Catheters were cut longitudinally to show thrombus formation on the interior of the catheter for NOrel (n=3) and control (n=3) catheters, and are shown via arrows. (B) Measurement of total clot area for control and NO-releasing catheters.

Figure 7.

Bacteria counts (CFU/cm2) after 9 d implantation in rabbits. NOrel and control catheters were homogenized in sterile PBS after explantation, and this solution was grown on agar for plate counting.

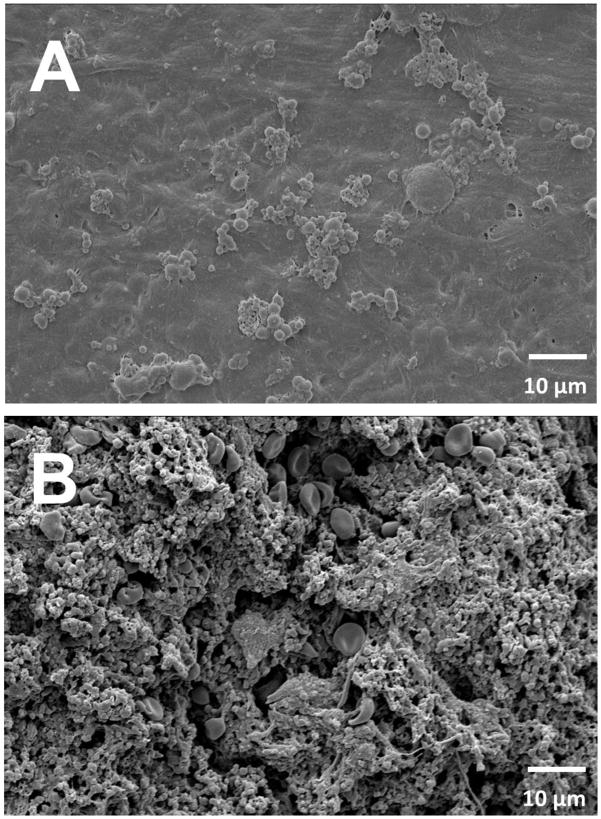

As shown in the SEM images (Fig. 8), the NO-releasing CVCs consistently showed significantly fewer adhered platelets, with little gross thrombus formation (Figure 6A), but did show signs of fibrin formation and protein adhesion on their surfaces [52]. Nitric oxide releasing surfaces have been reported to have high fibrinogen adsorption [52]. In contrast, the E2As control catheters were covered with a thick layer of thrombus which made it difficult to distinguish between the various blood components (activated platelets, fibrin, and entrapped red blood cells, etc.) and adhered bacteria. Overall utilizing DBHD/NONO and PLGA additives within the Elast-eon polymer shows significant promise in reducing rates of thrombosis and infection associated with CVC and potentially other blood-contacting devices.

Figure 8.

Representative SEM images of (A) NO-releasing and (B) control catheters after explanation.

4. Conclusions

In this study, NO-releasing central venous catheters were fabricated using Elast-eon E2As polymer with DBHD/NONO and PLGA additives, and the formulation was optimized for extended NO release using two different PLGA additives with ester end groups. E2As containing 10 weight% 50507E PLGA and 25 weight% DBHD/NONO was found to provide the most controlled NO release over the 9 day period, and was shown to release NO at physiological levels over 14 days. This composition was evaluated for its biocompatibility both in vitro and in vivo. The final composition showed a 0% hemolytic index when exposed to rabbit blood, and was found to be noncytotoxic (grade 0) to L292 mouse fibroblasts. The optimized NO-releasing CVCs were implanted in rabbits for a 9 d period to observe the potential to prevent clotting and infection. The NO-releasing CVCs were found to significantly reduce clot formation (7 times reduction) and bacterial adhesion (95% reduction). These encouraging results demonstrate that NO-releasing materials have the potential to improve the hemocompatibility and antibacterial properties of a wide range of biomedical devices for long-term applications.

Statement of Significance.

Clotting and infection are significant complications associated with central venous catheters (CVCs). While nitric oxide (NO) releasing materials have been shown to reduce platelet activation and bacterial infection in vitro and in short-term animal models, longer-term success of NO-releasing materials to further study their clinical potential has not been extensively evaluated to date. In this study, we evaluate diazeniumdiolate based NO-releasing CVCs over a 9 d period in a rabbit model. The explanted NO-releasing CVCs were found to have significantly reduced thrombus area and bacterial adhesion. These NO-releasing coatings can improve the hemocompatibility and bactericidal activity of intravascular catheters, as well as other medical devices (e.g., urinary catheters, vascular grafts).

Acknowledgments

The authors declare this work is supported by the National Institutes of Health, Grant K25HL111213. The authors wish to thank AorTech International for the gift of Elast-eon E2As polymer.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ratner BD. The catastrophe revisited: blood compatibility in the 21st century. Biomaterials. 2007;28:5144–7. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.07.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brisbois EJ, Davis RP, Jones AM, Major TC, Bartlett RH, Meyerhoff ME, Handa H. Reduction in thrombosis and bacterial adhesion with 7 day implantation of S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP)-doped Elast-eon E2As catheters in sheep. Journal of Materials Chemistry B. 2015 doi: 10.1039/C4TB01839G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robinson T, Kickler TS, Walker LK, Ness P, Bell W. Effect of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation on platelets in newborns. Critical care medicine. 1993;21:1029–34. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199307000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dillon PA, Foglia RP. Complications associated with an implantable vascular access device. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2006;41:1582–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2006.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaffney AM, Wildhirt SM, Griffin MJ, Annich GM, Radomski MW. Extracorporeal life support. BMJ. 2010;341:c5317-c. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c5317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vertes A, Hitchins V, Phillips KS. Analytical challenges of microbial biofilms on medical devices. Analytical chemistry. 2012;84:3858–66. doi: 10.1021/ac2029997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casey LA, Elliott SJT. Prevention of central venous catheter-related infection: update. British Journal of Nursing. 2010;19:78–87. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2010.19.2.46289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Grady NP, Alexander M, Dellinger EP, Gerberding JL, Heard SO, Maki DG, Masur H, McCormick RD, Mermel LA, Pearson ML. Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter–related infections. Clinical infectious diseases. 2002;35:1281–307. doi: 10.1086/502007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kluger D, Maki D. The relative risk of intravascular device related bloodstream infections in adults. 39th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy; San Francisco, CA: American Society for Microbiology; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sunenshine RH, Wright M-O, Maragakis LL, Harris AD, Song X, Hebden J, Cosgrove SE, Anderson A, Carnell J, Jernigan DB. Multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter infection mortality rate and length of hospitalization. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:97–103. doi: 10.3201/eid1301.060716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dijkshoorn L, Nemec A, Seifert H. An increasing threat in hospitals: multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2007;5:939–51. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Høiby N, Ciofu O, Johansen HK, Song Z-j, Moser C, Jensen PØ, Molin S, Givskov M, Tolker-Nielsen T, Bjarnsholt T. The clinical impact of bacterial biofilms. International journal of oral science. 2011;3:55. doi: 10.4248/IJOS11026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alcantar NA, Aydil ES, Israelachvili JN. Polyethylene glycol-coated biocompatible surfaces. Journal of biomedical materials research. 2000;51:343–51. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(20000905)51:3<343::aid-jbm7>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holmberg K, Bergström K, Stark M-B. Poly (Ethylene Glycol) Chemistry. Springer; 1992. Immobilization of proteins via PEG chains; pp. 303–24. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gölander C-G, Herron JN, Lim K, Claesson P, Stenius P, Andrade J. Poly (ethylene glycol) Chemistry. Springer; 1992. Properties of immobilized PEG films and the interaction with proteins; pp. 221–45. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee JH, Lee HB, Andrade JD. Blood compatibility of polyethylene oxide surfaces. Progress in Polymer Science. 1995;20:1043–79. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andrade J, Hlady V, Jeon S-I. Polyethylene oxide and protein resistance: principles, problems, and possibilities. Polymeric Materials: Science and Engineering. 1993:60–1. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harris JM. Poly (ethylene glycol) chemistry: biotechnical and biomedical applications. Springer Science & Business Media; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brisbois EJ, Handa H, Meyerhoff ME. Advanced Polymers in Medicine. Springer; 2015. Recent Advances in Hemocompatible Polymers for Biomedical Applications; pp. 481–511. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aksoy AE, Hasirci V, Hasirci N. Macromolecular symposia. Wiley Online Library; 2008. Surface modification of polyurethanes with covalent immobilization of heparin; pp. 145–53. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Basmadjian D, Sefton M. Relationship between release rate and surface concentration for heparinized materials. Journal of biomedical materials research. 1983;17:509–18. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820170310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kang I-K, Kwon OH, Kim MK, Lee YM, Sung YK. In vitro blood compatibility of functional group-grafted and heparin-immobilized polyurethanes prepared by plasma glow discharge. Biomaterials. 1997;18:1099–107. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(97)00035-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liang Y, Kiick KL. Heparin-functionalized polymeric biomaterials in tissue engineering and drug delivery applications. Acta biomaterialia. 2014;10:1588–600. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.07.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou Z, Meyerhoff ME. Preparation and characterization of polymeric coatings with combined nitric oxide release and immobilized active heparin. Biomaterials. 2005;26:6506–17. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.04.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen Y-M, Dai A-P, Shi Y, Liu Z-J, Gong M-F, Yin X-B. Effectiveness of silver-impregnated central venous catheters for preventing catheter-related blood stream infections: a meta-analysis. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2014;29:279–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2014.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Radomski MW, Palmer RM, Moncada S. The role of nitric oxide and cGMP in platelet adhesion to vascular endothelium. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 1987;148:1482–9. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(87)80299-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vaughn MW, Kuo L, Liao JC. Estimation of nitric oxide production and reactionrates in tissue by use of a mathematical model. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 1998;274:H2163–H76. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.274.6.H2163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Regev-Shoshani G, Ko M, Miller C, Av-Gay Y. Slow release of nitric oxide from charged catheters and its effect on biofilm formation by Escherichia coli. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2010;54:273–9. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00511-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ren H, Colletta A, Koley D, Wu J, Xi C, Major TC, Bartlett RH, Meyerhoff ME. Thromboresistant/anti-biofilm catheters via electrochemically modulated nitric oxide release. Bioelectrochemistry. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.bioelechem.2014.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nablo BJ, Chen T-Y, Schoenfisch MH. Sol-gel derived nitric-oxide releasing materials that reduce bacterial adhesion. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2001;123:9712–3. doi: 10.1021/ja0165077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nablo BJ, Schoenfisch MH. Antibacterial properties of nitric oxide–releasing sol-gels. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 2003;67:1276–83. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.20030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martinez LR, Han G, Chacko M, Mihu MR, Jacobson M, Gialanella P, Friedman AJ, Nosanchuk JD, Friedman JM. Antimicrobial and healing efficacy of sustained release nitric oxide nanoparticles against Staphylococcus aureus skin infection. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2009;129:2463–9. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Souza GFP, Yokoyama-Yasunaka JKU, Seabra AB, Miguel DC, de Oliveira MG, Uliana SRB. Leishmanicidal activity of primary S-nitrosothiols against Leishmania major and Leishmania amazonensis: Implications for the treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Nitric Oxide. 2006;15:209–16. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2006.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seabra AB, de Souza GFP, da Rocha LL, Eberlin MN, de Oliveira MG. S-Nitrosoglutathione incorporated in poly(ethylene glycol) matrix: potential use for topical nitric oxide delivery. Nitric Oxide. 2004;11:263–72. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Annich GM, Meinhardt JP, Mowery KA, Ashton BA, Merz SI, Hirschl RB, Meyerhoff ME, Bartlett RH. Reduced platelet activation and thrombosis in extracorporeal circuits coated with nitric oxide release polymers. Critical Care Medicine. 2000;28:915–20. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200004000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schoenfisch MH, Mowery KA, Rader MV, Baliga N, Wahr JA, Meyerhoff ME. Improving the Thromboresistivity of Chemical Sensors via Nitric Oxide Release: Fabrication and in Vivo Evaluation of NO-Releasing Oxygen-Sensing Catheters. Analytical Chemistry. 2000;72:1119–26. doi: 10.1021/ac991370c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goudie MJ, Brisbois EJ, Pant J, Thompson A, Potkay JA, Handa H. Characterization of an S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine–based nitric oxide releasing polymer from a translational perspective. International Journal of Polymeric Materials and Polymeric Biomaterials. 2016;65:769–78. doi: 10.1080/00914037.2016.1163570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Major TC, Brant DO, Reynolds MM, Bartlett RH, Meyerhoff ME, Handa H, Annich GM. The attenuation of platelet and monocyte activation in a rabbit model of extracorporeal circulation by a nitric oxide releasing polymer. Biomaterials. 2010;31:2736–45. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Handa H, Major TC, Brisbois EJ, Amoako KA, Meyerhoff ME, Bartlett RH. Hemocompatibility comparison of biomedical grade polymers using rabbit thrombogenicity model for preparing nonthrombogenic nitric oxide releasing surfaces. Journal of Materials Chemistry B. 2014;2:1059–67. doi: 10.1039/C3TB21771J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Handa H, Brisbois EJ, Major TC, Refahiyat L, Amoako KA, Annich GM, Bartlett RH, Meyerhoff ME. In vitro and in vivo study of sustained nitric oxide release coating using diazeniumdiolate-doped poly (vinyl chloride) matrix with poly (lactide-co-glycolide) additive. Journal of Materials Chemistry B. 2013;1:3578–87. doi: 10.1039/C3TB20277A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cai W, Wu J, Xi C, Meyerhoff ME. Diazeniumdiolate-doped poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid)-based nitric oxide releasing films as antibiofilm coatings. Biomaterials. 2012;33:7933–44. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Batchelor MM, Reoma SL, Fleser PS, Nuthakki VK, Callahan RE, Shanley CJ, Politis JK, Elmore J, Merz SI, Meyerhoff ME. More lipophilic dialkyldiamine-based diazeniumdiolates: synthesis, characterization, and application in preparing thromboresistant nitric oxide release polymeric coatings. J Med Chem. 2003;46:5153–61. doi: 10.1021/jm030286t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu B. PhD Dissertation. University of Michigan; Ann Arbor: 2009. Development of hemocompatible polymeric materials for blood-contacting medical devices. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brisbois EJ, Bayliss J, Wu J, Major TC, Xi C, Wang SC, Bartlett RH, Handa H, Meyerhoff ME. Optimized polymeric film-based nitric oxide delivery inhibits bacterial growth in a mouse burn wound model. Acta Biomaterialia. 2014;10:4136–42. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Batchelor MM, Reoma SL, Fleser PS, Nuthakki VK, Callahan RE, Shanley CJ, Politis JK, Elmore J, Merz SI, Meyerhoff ME. More Lipophilic Dialkyldiamine-Based Diazeniumdiolates: Synthesis, Characterization, and Application in Preparing Thromboresistant Nitric Oxide Release Polymeric Coatings. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2003;46:5153–61. doi: 10.1021/jm030286t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Klement P, Du YJ, Berry LR, Tressel P, Chan AKC. Chronic performance of polyurethane catheters covalently coated with ATH complex: A rabbit jugular vein model. Biomaterials. 2006;27:5107–17. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Simmons A, Padsalgikar AD, Ferris LM, Poole-Warren LA. Biostability and biological performance of a PDMS-based polyurethane for controlled drug release. Biomaterials. 2008;29:2987–95. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cozzens D, Luk A, Ojha U, Ruths M, Faust R. Surface characterization and protein interactions of segmented polyisobutylene-based thermoplastic polyurethanes. Langmuir. 2011;27:14160–8. doi: 10.1021/la202586j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Major TC, Brisbois EJ, Jones AM, Zanetti ME, Annich GM, Bartlett RH, Handa H. The effect of a polyurethane coating incorporating both a thrombin inhibitor and nitric oxide on hemocompatibility in extracorporeal circulation. Biomaterials. 2014;35:7271–85. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.05.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shenderova A, Ding AG, Schwendeman SP. Potentiometric method for determination of microclimate pH in poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) films. Macromolecules. 2004;37:10052–8. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brisbois EJ, Handa H, Major TC, Bartlett RH, Meyerhoff ME. Long-term nitric oxide release and elevated temperature stability with S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP)-doped Elast-eon E2As polymer. Biomaterials. 2013;34:6957–66. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.05.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lantvit SM, Barrett BJ, Reynolds MM. Nitric oxide releasing material adsorbs more fibrinogen. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 2013;101:3201–10. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]