Abstract

OBJECTIVES

Currently, there is no curative treatment for dementia. Two anti-dementia drug classes are approved for treatment of symptoms but the magnitude of benefit is small, raising questions about how clinicians use them balanced against risks and cost. The objective is to evaluate frequency of use, whether populations most likely to benefit are treated, and correlates of treatment initiation.

DESIGN

Nationally representative cohort study.

SETTING

Fee-for-service Medicare.

PARTICIPANTS

433,559 elderly patients with dementia, enrolled in Part A, B and D in 2009 and the subset with incident dementia (N=185,449).

MEASUREMENTS

Main outcome is any prescription fill for anti-dementia drugs cholinesterase inhibitors [ChEI] or memantine) within one year.

RESULTS

Treatment with anti-dementia drugs occurred in 55.8% of all dementia patients and 49.3% of incident dementia. There was no difference between ChEI and memantine use by dementia severity measured by death within first year or living in residential care vs. in a community setting) even though memantine is not indicated in mild disease. Among incident cases, initiation of treatment was lower in residential care (RR:0.82, CI:0.81-0.83) and with more comorbidities (RR:0.96, CI:0.96-0.96). Sixty percent of patients were managed by primary care alone. Seeing neurology or psychiatry was associated with higher likelihood of treatment (RR:1.07, CI:1.06 -1.09; RR:1.17, CI:1.16 -1.19) and geriatrics with lower RR:0.96, CI:0.93-0.99) relative to primary care alone. Across the United States, the proportion of newly diagnosed patients started on anti-dementia treatment varied from 32% to 66% across hospital referral regions HRR).

Limitations

Clinical details are not in claims data and can only be approximated.

CONCLUSION

Anti-dementia drugs are less often used in people with late disease but there is not differentiation in medication choice. While primary care providers most often prescribe anti-dementia medication without specialty support, differences in practice between specialties are evident.

Keywords: Dementia, drug treatment, Medicare

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is increasingly being brought to the attention of the American public, health care providers, and policy makers because of the enormous burden it places on families, the financial costs, and the projected tripling in number of affected adults over the next 40 years 1–4.

The National Alzheimer's Project Act 5, passed in 2011, has focused attention at a national level on ways to mitigate the impact of dementia on current and future populations by developing supportive policies and increasing funding for research. Currently there is no curative treatment and much of the increased research funding is targeted toward discovering therapies that prevent AD's onset or alter its course.

There are two FDA-approved drug classes currently available for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease, cholinesterase-inhibitors ChEI), including rivastigmine, donepezil and galantamine, and the NMDA-receptor-antagonist memantine, together called “anti-dementia drugs.” Studies on ChEI have shown small positive effects for Alzheimer's disease and mixed effects in other common dementias (vascular, Lewy-body and Parkinson's)6–8. ChEIs have an indication in early to moderate disease, donepezil and rivastigmine were later also approved for severe dementia 9–12. Trials for memantine show benefit in Alzheimer's disease but less so in other dementias, and its indication is for moderate to severe dementia, not in mild disease 13,14. However, results across studies are inconsistent, and there is disagreement about whether the magnitude of benefit outweighs risk, especially for ChEI 10,15,16. The uncertainty about the value of treatment is reflected in differences between guidelines for treatment across specialties and countries 9,17–20.

Even with this uncertainty about effectiveness, anti-dementia drugs are in the top 15 drugs prescribed by cost in Medicare Part D, accounting for 3.5% of total Part D spending21. And Aricept, the brand name version of donepezil, was in the top 10 most common brand-name drugs prescribed in Part D and had the highest median negotiated price in 2008 among that top 10 list 22,23, although now it is generic.

These drugs may be so commonly used because clinicians and families are willing to try treatments with low efficacy when in the challenging situation of managing a person with progressive cognitive loss that is also associated with difficult behaviors and psychotic symptoms. Trials suggest the magnitude of anti-dementia drugs benefit are small relative to non-pharmacologic management strategies 24 and delivery of comprehensive primary care that incorporates caregiver support 25. But instituting those interventions is more challenging for busy clinicians than writing a prescription 26. The problem is that these medications may have high financial cost, low effectiveness, and side effects 27–30.

Given the cost and uncertainty about benefit, evaluation of how these drugs are being used can identify where practice improvement is needed. In this study using a national sample of Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in Part D, we evaluate the frequency of anti-dementia drug use among people with a diagnosis of dementia. To compare patients at similar disease severity, we then report on treatment among patients with a first dementia diagnosis and factors associated with likelihood of treatment initiation. We hypothesize that dementia severity decreases the likelihood that a person receives anti-dementia treatment and influences whether ChEI or memantine is used. While some ChEIs now have an indication for severe disease, guidelines and opinions suggest their use should be avoided in late stage disease10,31 and in contrast memantine should predominantly be used in severe disease and not used in mild disease 14. We also test how other factors influence likelihood of treatment including whether a dementia specialist neurologist, psychiatrist, or geriatrician) was involved in care. Finally we examine regional differences in use of anti-dementia drug use across the United States.

METHODS

Study Sample

The study sample includes Part D enrollees 2008 – 2010 drawn from a 40% sample of Medicare beneficiaries, 50% of whom were enrolled in Part D. Patients were selected when they had an index claim with a dementia diagnosis in the year 2009 using ICD-9 diagnostic codes from the Chronic Condition Warehouse.1 Inclusion requirements were age 66 years and older, continuous enrollment in Medicare Parts A and B one year before and Part D four months before the index diagnosis and Part A, B, and D 12 months after index diagnosis. Patients who died within the first 90 days of observation, which limited the opportunity for medication treatment, were excluded from the analysis. Patients were categorized as incident cases if the index diagnosis was preceded by a 12-month diagnosis-free period.

We used an inclusive approach to capturing dementia rather than split by sub-types because of the limitations inherent in claims. Claims have good specificity for dementia but lack sensitivity, under-ascertaining early disease 32,33, and they do not differentiate well between the types of dementia 33–36. In addition, clinicians who provide the diagnosis have difficulty distinguishing type and even expert approaches sometimes do not agree 37–40. We opted for the inclusive approach rather than creating what might be essentially arbitrary groups by type of dementia.

Measures

Our main outcome is at least one prescription fill for an anti-dementia drug in the year after the first appearance of a dementia diagnosis. The Lexi-Data Basic database was used to identify drugs according to the National Drug Code 41.

Age, sex, race and Hospital Referral Regions (HRR) of residence were obtained from the beneficiary summary file. Additional control variables were: receipt of low-income subsidy from Part D records), comorbidities, and evaluation and management visits and hospitalizations during the year prior to diagnosis. Comorbidity count was based on the Deyo-Charlson Comorbidity Index excluding dementia 42,43. We also counted survived days to account for death in the observation period. We captured visits to a neurologist, psychiatrist or geriatrician or more than one type in the two months prior or after the date of the initial diagnosis as an indicator of specialty involvement.

We were concerned that analysis of type of specialty visited may be confounded by whether the person had comorbid behavioral or psychotic symptoms. To adjust for presence of psychiatric or behavioral symptoms, we used fills for psychopharmacologic drugs in the year prior to index diagnosis in these six drug classes: benzodiazepines, second generation sedatives, first generation antipsychotics, atypical antipsychotics, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors SSRI/SNRI), and older-generation antidepressants tetra- and tri-cyclics). Use was quantified as the count of unique psychopharmacologic medication classes prescribed.

Administrative data do not contain clinical information on the severity of dementia so we developed a proxy based on whether the patient lived in residential care nursing home, assisted living or other types of board-and-care facilities). If patients received at least 50% of their prescriptions through a longterm care pharmacy in the four months preceding their index diagnosis in 2009, they were considered in residential care as opposed to community-dwelling. Because the measure may be imperfect in its correlation with dementia severity, we also report anti-dementia drug use among people who die within a year of index diagnosis versus those who did not.

Analysis

Descriptive analysis was performed for all diagnosed dementia cases and incident dementia patients. To test for potential prescribing differences between ChEI and memantine, these classes were initially examined separately. A sensitivity analysis tested whether enrollment in hospice, which covers some medications, influenced treatment rates and we found no difference in anti-dementia or psychopharmacologic medication use between hospice and non-hospice enrollees.

Multivariate regression modeling was performed to estimate the probability of receiving a prescription of anti-dementia drugs among the newly diagnosed beneficiaries. Because the outcome was common, we used Poisson regression with robust error variance to estimate relative risks 44. The model included demographic factors, survived days, baseline year healthcare utilization, low income subsidy, HRR, clinical factors psychopharmacologic co-medication, comorbidity, and dementia severity proxy) and specialty involvement. Use of ChEI and memantine were initially modeled separately which showed no differences in the association of factors with likelihood of prescription from the combined outcome of anti-dementia medications grouped together.

Regional use by HRR was adjusted for population age, gender, race, and low income subsidy using the indirect method and grouped into quintiles of adjusted treatment rates.

All analyses were performed with SAS (Version 9.2), and the map was produced with ESRI ArcGIS Desktop (Version 10.2). This study had expedited IRB approval.

RESULTS

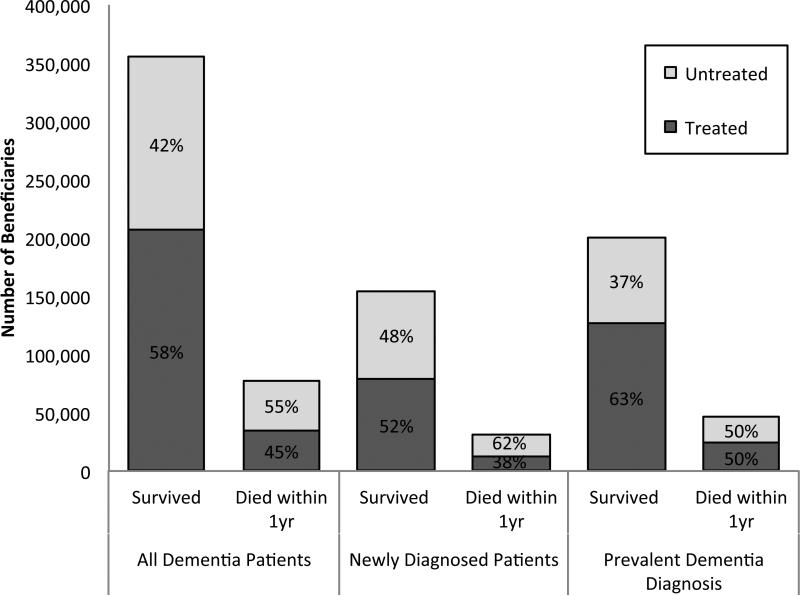

There were 433,559 patients who had a dementia diagnosis in 2009 (Table 1) in this fee-for-service Medicare sample. Over half of them (55.8%) received a prescription for anti-dementia drugs. Treated patients were slightly younger than those not treated (82.7 vs. 83.7 years, p<0.001) but there was no gender difference in treatment. White and Hispanic patients received a prescription more often, as do patients with less severe dementia, while Black patients and people receiving low-income subsidy were less frequently treated. Eighteen percent of patients with dementia died within a year of the index diagnosis, 45% of whom were treated with an anti-dementia drug (Figure 1). From prescription fill data, we are unable to assess whether medications are taken simultaneously or in sequence, but 46.7% of patients received only ChEI, 40.9% filled both ChEI and memantine, and 12.4% filled only memantine. There were no meaningful differences between the percentage of people treated with ChEI compared to memantine by dementia severity proxy or level of comorbidity. For the remainder of the study, we report results combining the two classes.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Medicare Fee-for-Service Beneficiaries enrolled in Part D with a Diagnosis of Dementia in 2009 by whether Treated with Cholinesterase Inhibitor (ChEI), Memantine, or Either for Dementia

| All Diagnosed Dementia Patients | Diagnosed Dementia Patients stratified by Antidementia drug prescription in year after index diagnosis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | ChEI | Memantine | Either | ||

| N (%) | 433559 | 191592 (44.2%) | 211920 (48.9%) | 128929 (29.7%) | 241967 (55.8%) |

| Age mean (± SD) | 83.2 | 83.7 (±8.1) | 82.6 (±7.0) | 82.5 (±6.9) | 82.7 (±7.0) |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 115737 (26.7%) | 50766 (26.5%) | 57196 (27.0%) | 34661 (26.9%) | 64971 (26.9%) |

| Female | 317822 (73.3%) | 140826 (73.5%) | 154724 (73.0%) | 94268 (73.1%) | 176996 (73.2%) |

| Race/ Ethnicity | |||||

| White | 354499 (81.8%) | 155079 (80.9%) | 174513 (82.4%) | 108044 (83.8%) | 199420 (82.4%) |

| Black | 50530 (11.7%) | 24385 (12.7%) | 23052 (10.4%) | 12657 (9.8%) | 26145 (10.8%) |

| Other | 6090 (1.4%) | 2945 (1.5%) | 2712 (1.3%) | 1608 (1.3%) | 3145 (1.3%) |

| Asian | 8060 (1.9%) | 3456 (1.8%) | 4078 (1.9%) | 2162 (1.7%) | 4604 (1.9%) |

| Hispanic | 14380 (3.3%) | 5727 (3.0%) | 7565 (3.6%) | 4458 (3.5%) | 8653 (3.6%) |

| Part D low-income subsidy | 253989 (58.6%) | 121529 (63.4%) | 115752 (54.6%) | 68985 (53.5%) | 132460 (54.7%) |

| Died within Year of Index Diagnosis | 78125 (18.0%) | 42700 (22.3%) | 30198 (14.3%) | 18309 (14.2%) | 35425 (14.6%) |

| Newly diagnosed in 2009 | 185449 (42.8%) | 94081 (49.1%) | 80600 (38.0%) | 41402 (32.1%) | 91368 (37.8%) |

| Proxy for Dementia Severity N(%) | |||||

| Community-Dwelling | 262659 (60.6%) | 106142 (55.4%) | 137854 (65.1%) | 82308 (63.8%) | 156517 (64.7%) |

| In Residential Care | 170900 (39.4%) | 85450 (44.6%) | 74066 (35.0%) | 46621 (36.2%) | 85450 (35.3%) |

Figure 1.

Treatment with anti-dementia Drugs among Medicare Fee-for-Service Part D Beneficiaries with a Prevalent or New Diagnosis of Dementia in 2009

*Note: Died within a year of the first occurrence of a claims with a diagnosis representing dementia in 2009

Of all dementia patients, 185,449 had a new diagnosis. Incident dementia patients were less likely to receive a prescription in the following year than prevalent cases 49.3% vs. 60.7%, p<0.001). Table 2 shows the differences between treated and untreated patients among beneficiaries with incident dementia. The 49% who were treated with anti-dementia drugs were younger, slightly less likely to be male or Black, more likely Hispanic, and had fewer comorbid conditions. Treated patients also had less severe dementia as indicated by our proxy measure 19.1% of treated patients lived in residential care vs. 28.5% of the untreated, p<.0001) and less likely to die within the year 12.8% vs. 20.3%, p<.0001).

Table 2.

Characteristics of Medicare Fee-for-Service Beneficiaries enrolled in Part D with a New Diagnosis of Dementia in 2009 by whether Treated with an Anti-Dementia Drug or Not

| All Newly Diagnosed Dementia Patients | Filled Prescription for any Anti-Dementia Drug | No Anti-Dementia drug Prescription Fill | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N(%)/mean(s.d.) | N(%)/mean(s.d.) | N(%)/mean(s.d.) | |

| N | 185449(100%) | 91368 (49.3%) | 94081 (50.7%) |

| Age mean (± SD) | 82.5 | 82.1 (± 7.07) | 82.8 (± 8.15) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 53224 (28.7%) | 25847 (28.3%) | 27377 (29.1%) |

| Female | 132225 (71.3%) | 65521 (71.7%) | 66704 (70.9%) |

| Race/ Ethnicity | |||

| White | 151493 (81.7%) | 75512 (82.7%) | 75981 (80.8%) |

| Black | 20573 (11.1%) | 9026 (9.9%) | 11547 (12.3%) |

| Other race | 2848 (1.5%) | 1288 (1.4%) | 1560 (1.66%) |

| Asian | 4189 (2.3%) | 2126 (2.3%) | 2063 (2.2%) |

| Hispanic | 6346 (3.42%) | 3416 (3.7%) | 2930 (3.1%) |

| Part D low-income subsidy | 94144 (50.8%) | 42583 (46.6%) | 51561 (54.8%) |

| Died within Year of First Diagnosis | 30767 (16.6%) | 11669 (12.8%) | 19098 (20.3%) |

| Comorbidity Count | 2.34 | 2.07 (± 1.74) | 2.60 (±1.89) |

| Psychopharm Comedication Count | 0.67 | 0.68 (±0.80) | 0.66 (±0.81) |

| Proxy for Dementia Severity N (%) | |||

| Community-Dwelling | 141235 (76.2%) | 73962 (81.0%) | 67273 (71.5%) |

| In Residential Care | 44214 (23.8%) | 17406 (19.1%) | 26808 (28.5%) |

| Visited Dementia Specialist | |||

| None | 111539 (60.1%) | 53369 (58.4%) | 58170 (61.8%) |

| Psychiatrist | 23446 (12.6%) | 10911(11.9%) | 12535 (13.3%) |

| Neurologist | 33434 (18.0%) | 19187 (21.0%) | 14247 (15.1%) |

| Geriatrician | 5160 (2.8%) | 2228 (2.4%) | 2932 (3.1%) |

| More than 1 type | 11870 (6.4%) | 5673 (6.2%) | 6197 (6.6%) |

To further characterize differences between treatment groups, we examined drugs to treat psychiatric issues. People treated with psychopharmacologic drugs prior to dementia diagnosis received anti-dementia drugs more often than those not 57.9% vs. 53.0%, p<0.001). The Appendix table shows the specific class of psychopharmacologic prescriptions received stratified by the proxy for dementia severity and by specialty involvement, which confirms that patients who have been receiving these drugs are more likely to see psychiatrists. Of note, treatment with firstSgeneration antipsychotics and older antidepressants was low (≤ 5%) across all groups, consistent with recommendations against use of these classes45–47.

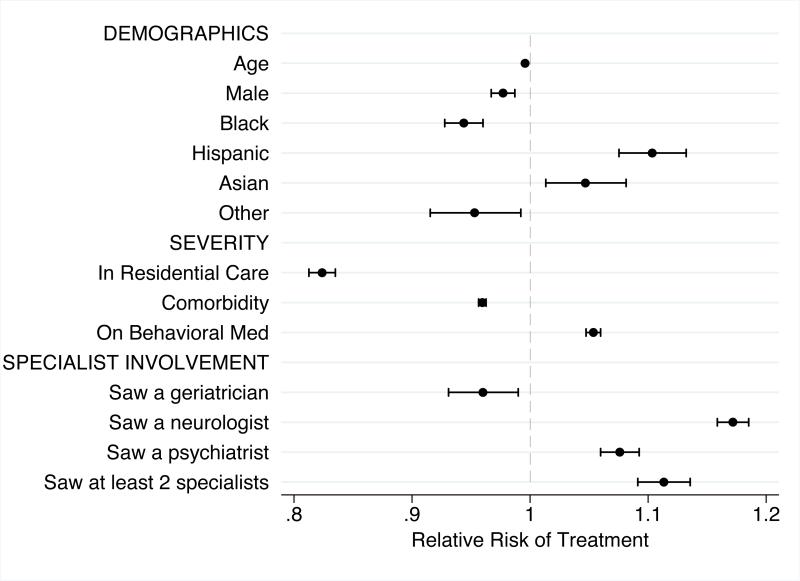

Figure 2 shows the modeled relative risk of anti-dementia drug treatment. When controlled for all other factors, neither age (RR: 0.99, CI: .995-.997) nor gender (RR: 0.98, CI: .97-.99) show a meaningful relationship with treatment. Race/ethnicity findings were specific to group with Blacks (RR: 0.94, CI: .93-.96) less likely and Hispanics (RR: 1.10, CI: 1.07-1.13) and Asians (RR: 1.05, CI: 1.01-1.08) more likely than Whites to be treated. Patients on psychopharmacologic medications were more likely to be treated (RR: 1.05, CI: 1.05 -1.06). Compared to those community-dwelling patients, patients in residential care had lower probability of receiving an anti-dementia drug (RR: 0.82, CI: 0.81-0.83) and each additional comorbid condition had a negative effect (RR: 0.96, CI: 0.96- 0.96). The type of specialist seen also influenced the probability of receiving anti-dementia drugs. A visit to a geriatrician near the time of diagnosis was associated with 4% lower risk of a medication fill, while a psychiatrist visit or neurologist visit was associated with an 8% and 17% higher risk of anti-dementia drug treatment respectively.

Figure 2.

Modeled Association of Beneficiary Characteristics with Treatment with Anti-dementia Drug within 1 year of Newly Diagnosed Dementia

Note: Model also adjusted for individual low income subsidy status, number of survived days, visits and hospitalizations in year prior to diagnosis, and Hospital Referral Region of residence

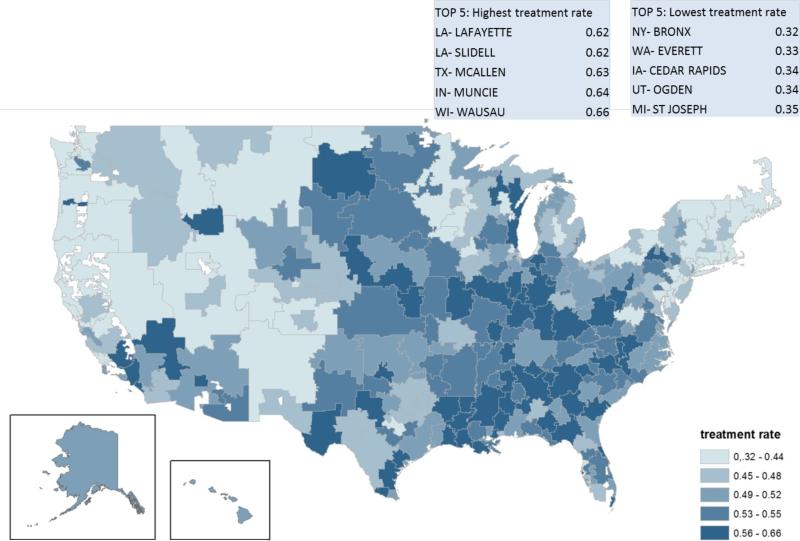

Figure 3 maps treatment rates for newly diagnosed dementia patients across the United States adjusted for age, sex, race and low-income subsidy use. The percent of people with newly identified dementia treated with anti-dementia drugs varied from 32% in the Bronx, NY to 66% in Wausau, WI.

Figure 3.

Variation in Treatment with anti-dementia Drugs across Hospital Referral Regions HRR) of the United States, adjusted for population differences in age, gender, race, and low income subsidy status

CONCLUSIONS

More than half of all people with a recognized dementia diagnosis, according to the physicians who bill for their care, receive anti-dementia drugs. People who are newly diagnosed have a 50:50 chance of being treated. In accordance with guidelines, people who appear to be in later stages of dementia are less likely to be treated but there is no difference between use of ChEI or memantine related to any of the proxy measures for dementia severity. People who have comorbid psychiatric symptoms are more likely to receive an anti-dementia drug. Factors not directly related to disease, such as race and region of residence, also influence treatment rates. Finally, the type of clinician involved in care may independently influence whether or not a person is treated.

Several findings suggest areas for improvement in anti-dementia drug treatment. One area is better targeting of the drug for the right population. Our expectation was a higher proportion of newly diagnosed people would receive treatment than people with prevalent or longer standing disease and that there would be a differentiation between use of ChEI versus memantine, but we found neither. The second potential area is to understand better the independent association of higher likelihood of anti-dementia treatment when other psychopharmacologic treatments are being used. The anti-dementia drugs have small if any effect on other psychiatric symptoms48,49. Further efforts are needed to explore whether clinicians are aware of the small benefit and availability and effectiveness of non-pharmacologic approaches. And lastly, two-fold regional variation and differences among specialists suggests there may not yet be good consensus of what constitutes best practice, in spite of existing guidelines and syntheses of the evidence, which will make translating the current evidence into practice difficult.

These observed treatment levels need to be put in the context of previous reports. We find reported treatment rates vary greatly depending on country, by prevalent versus incident cases, the context (nursing home or not), and region of the United States (U.S.). Over 80% of observed patients in a Swedish study of prevalent cases were treated with anti-dementia drugs 50. In Spain, 53% of dementia patients were treated 51, and in Germany 27% of incidence cases received anti-dementia medication 52. And like the U.S., many people in Britain and Germany are managed by primary care, but when a specialist is seen anti-dementia drugs are more likely to be prescribed 52–54. Within the U.S., use has been studied at the end of life in nursing homes 55 and in the Medicare Current Beneficiaries Survey with self-reported or claims diagnosis, which found only 26% of people with dementia were treated 56. An apples-to-apples comparison between these studies is challenging because they use different types of data clinical, survey or billing date)34–36 and different definitions of dementia, a problem that has plagued epidemiologic estimates of dementia prevalence as well 57. The Dartmouth Atlas reported fourfold (from 3.7 to 17.1%) variation in per capita use 58 not per identified dementia case, combining likelihood of being diagnosed (which varies59) and likelihood of being treated into one measure. We find two-fold variation in the use of these drugs among those with newly diagnosed dementia, varying between 32% and 66% across HRRs.

Several conceptual models exist to explain large variations in clinical practice and the one developed by Chandra and Skinner provides helpful guidance in understanding the use of anti-dementia drugs based on their cost-effectiveness 60,61. Drugs can be effective with few tradeoffs, heterogeneous in effect because of dependency on appropriate patient selection, have low cost-effectiveness or limited evidence for effectiveness, or be ineffective because of evidence of harm 57. In this framework, anti-dementia drugs would be considered to have heterogeneous benefits and part of the variation in use could be due to differential expertise in targeting the population most likely to benefit. The trial evidence suggests that likelihood of benefit with ChEI versus memantine differs by disease severity so treatment should target patients by severity. But we observe no such pattern in actual practice suggesting that a major issue is appropriate selection of patients most likely to benefit. The additional observation, however, that specialists in the field have divergent care patterns suggests that perhaps there is disagreement among thought leaders as to whether these drugs offer value and hence treatment practices may vary based on limited evidence of effectiveness which is interpreted differently across providers.

The finding regarding involvement of specialists has important implications for healthcare delivery for people with dementia. When a specialist is seen, neurologists and psychiatrists are more likely and geriatricians less likely to prescribe anti-dementia drugs than when primary care manages alone. Yet importantly, 60% of people with newly diagnosed dementia are managed in primary care without input from dementia- care specialists. There is likely some residual confounding from the factors that lead a patient to choose to see a specialist or take medication. But the finding suggests that the uncertainty about treatment is not entirely random across physicians and highlights that improvement in care will need strong engagement from primary care providers.

The nature of the study design and data sources requires considering its limitations. First, as an observational study we test association but not causal relationships. There may be residual confounding particularly in the specialty finding. For example, if people who prefer more aggressive treatment also seek out neurologists, we may be detecting patient preference more than a specialty predilection. Second, we use proxies for disease severity and psychiatric symptoms because claims lack detailed clinical information, but the advantage of using administrative data is inclusion of diverse beneficiaries who may not be represented in community-based studies or research registries. Third, place of residence as a proxy for severity of dementia has face validity, but the time of transitioning from community-dwelling to residential care may be influenced by other factors in addition to disease severity 62–64. In addition, using longterm care pharmacy prescription fills as the indicator for residential care may represent differing levels of dementia severity depending on the type of facility, from board and care to nursing home. Our strategy to mitigate the heterogeneity of stage was to focus on people whose diagnosis appears to be new but even that approach may be imperfect given that diagnostic delay and late presentation is common for various reasons 65,66. Fourth, the indications for use of ChEI have changed since the time of our study expanding to severe disease for some ChEI, yet the evidence has not changed and evaluations of the benefit continue to assert their use should be limited in late stage disease 10,31. Also, the data analyzed shows utilization in the years 2008 to 2010. At the time the study was initiated these were the most recent Part D data available. While more recent data is desirable, the main results regarding correlates of treatment initiation are unlikely to be different because the state of evidence has not changed since 2010. Future studies including changes in drug usage over time would be an interesting next step. There is evidence that antipsychotic drug use has declined since the time of this study use among nursing home residents use declined from 23.8% in 2012 to 19.4% in 2014 67) but trends in anti-dementia drugs use have not yet been explored.

Implications

The human and cost implications of managing the growing population of people with dementia have garnered increased attention in the last several years. This study suggests that, even among the experts, we have not yet reached consensus about the best practice for anti-dementia medication management and treatment targeting can be improved. In addition, much of the medication management occurs in primary care. Dementia is under-recognized in primary care and primary care physicians report not feeling confident with the diagnosis68–70. Interventions and policies are needed to build expertise among primary care providers and to promote care that reflects best evidence. Those efforts should be designed to assure that all providers guide medication decisions based on realistic expectations of benefits and can share that information with patients and families with the goal of improving targeting of these medications.

Many of the initial recommendations of the National Advisory Council tasked by NAPA to develop a national strategy focused on finding curative or preventative treatments and more recently the scope has expanded toward building the supports needs for high quality community caregiving. While both of these areas are urgently needed, understanding what constitutes best practice in medical care and how best to deliver that care for this population is an equally important area.

ACKKNOWLEDGMENTS

The research and Dr. Bynum had funding support from NIA P01 AG19783

Sponsor's Role:

The study was supported by the National Institute of Aging grant P01 AG19783. DK. was a German Harkness Fellow for Health Policy of the Commonwealth Fund. Support for Dr. Koller was provided by The Commonwealth Fund. The views presented here are those of the authors and should not be attributed to The Commonwealth Fund or its directors, officers, or staff. No sponsor had a role in in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collections, analysis and preparation of paper.

Appendix

Appendix Table.

Psychopharmacologic Treatments in the Four Months Prior to First Diagnosis of Dementia among Medicare Fee-for-Service Beneficiaries enrolled in Part D with a New Diagnosis of Dementia in 2009

| Anti-Dementia and Behavioral Medication Prescription Use in Four Months prior to first dementia diagnosis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychopharmacologic Medication count, mean (± SD) | Benzodiazepine, number (%) | Second Generation Sedative, number (%) | First Generation Antipsychotic, number (%) | Atypical Antipsychotic, number (%) | SSRI/SNRI, number (%) | Older generation antidepressant, number (%) | |

| Proxy for Dementia Severity | |||||||

| Community-Dwelling | 0.59 (± 0.8) | 2839 (2.0%) | 15266 (10.8%) | 2008 (1.4%) | 14674 (10.4%) | 44584 (31.6%) | 6012 (4.3%) |

| In Residential Care | 0.92 (± 0.9) | 443 (0.2%) | 3949 (8.9%) | 1757 (4.0%) | 11893 (26.9%) | 21245 (48.1%) | 1111 (2.5%) |

| Visited Dementia Specialist | |||||||

| None | 0.59 (± 0.8) | 1548 (1.4%) | 9732 (8.7%) | 1753 (1.6%) | 13479 (12.1%) | 36319 (32.6%) | 3748 (3.4%) |

| Psychiatrist | 1.04 (± 0.9) | 522 (2.2%) | 3484 (14.9%) | 1209 (5.2%) | 7132 (30.4%) | 11336 (48.3%) | 932 (4.0%) |

| Neurologist | 0.59 (± 0.8) | 762 (2.3%) | 3680 (11.0%) | 324 (1.0%) | 2673 (8.0%) | 11030 (33.0%) | 1939 (4.9%) |

| Geriatrician | 0.61 (± 0.7) | 66 (1.3%) | 434 (8.4%) | 71 (1.4%) | 629 (12.2%) | 1855 (36.0%) | 135 (2.6%) |

| More than one specialty type | 0.9 (± 0.9) | 384 (3.2%) | 1885 (15.9%) | 408 (3.4%) | 2654 (22.4%) | 5289 (44.6%) | 669 (5.6%) |

Footnotes

Author Contributions:

JB organized access to data, DK and JB designed the concept. DK, TH and JB analyzed data and prepared the manuscript.

| Elements of Financial/Personal Conflicts |

*Author 1 DK |

Author 2 TH |

Author 3 JB |

Etc. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Employment or Affiliation | x | x | x | |||||

| Grants/Funds | x | x | x | |||||

| Honoraria | x | x | x | |||||

| Speaker Forum | x | x | x | |||||

| Consultant | x | x | x | |||||

| Stocks | x | x | x | |||||

| Royalties | x | x | x | |||||

| Expert Testimony | x | x | x | |||||

| Board Member | x | x | x | |||||

| Patents | x | x | x | |||||

| Personal Relationship | x | x | x | |||||

References

- 1.Prince MJ, Bryce R, Albanese E, et al. The global prevalence of dementia: A systematic review and metaanalysis. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9(1):63–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hebert LE, Weuve J, Scherr P, et al. Alzheimer disease in the United States (2010-2050) estimated using the 2010 census. Neurology. 2013;80(19):1778–83. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31828726f5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wimo A, Jönsson L, Bond J, et al. The worldwide economic impact of dementia 2010. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9(1):1–11. e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hurd MD, Martorell P, Delavande A, et al. Monetary costs of dementia in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(14):1326–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1204629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Alzheimer's Project Act. USA: 2011. Public Law 111 -375-Jan 4 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Birks J. Cholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer's disease. Cochrane database Syst Rev. 2006;(1):CD005593. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rolinski M, Fox C, Maidment I, et al. Cholinesterase inhibitors for dementia with Lewy bodies, Parkinson's disease dementia and cognitive impairment in Parkinson's disease. Cochrane database Syst Rev. 2012;3:CD006504. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006504.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Birks J, Craig D. Galantamine for vascular cognitive impairment. Cochrane database Syst Rev. 2006;4:CD004746. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004746.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qaseem A, Snow V, Cross JT, et al. Current pharmacologic treatment of dementia: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Academy of Family Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(5):370–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-5-200803040-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raina P, Santaguida P, Ismaila A, et al. Effectiveness of cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine for treating dementia: evidence review for a clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:379–397. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-5-200803040-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Federal Drug Administration [January 3, 2016];FDA Approves Expanded Use of Treatment for Patients With Severe Alzheimer's Disease. 2006 Available at: http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/2006/ucm1087 68.htm.

- 12.Medscape [January 3, 2016];FDA Approves Exelon Patch for Severe Alzheimer's. 2013 Available at: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/807062.

- 13.McShane R, Areosa Sastre A, Minakaran N. Memantine for dementia. Cochrane database Syst Rev. 2006;(2):CD003154. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003154.pub5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schneider LS, Dagerman KS, Higgins JPT, et al. Lack of evidence for the efficacy of memantine in mild Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2011;68(8):991–8. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kavirajan H, Schneider LS. Efficacy and adverse effects of cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine in vascular dementia: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(9):782–92. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70195-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaduszkiewicz H, Bachmann C, van den Bussche H. Telling “the truth” in dementia--do attitude and approach of general practitioners and specialists differ? Patient Educ Couns. 2008;70(2):220–226. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herrmann N, Gauthier S. Diagnosis and treatment of dementia: 6. Management of severe Alzheimer disease. Can Med Assoc J. 179(12):1279–1287. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.070804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakamura S, Article R. A guideline for the treatment of dementia in Japan. Intern Med. 2004;43(1):18–29. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.43.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hort J, O'Brien JT, Gainotti G, et al. EFNS guidelines for the diagnosis and management of Alzheimer's disease. Eur J Neurol. 2010;17(10):1236–1248. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.NICE Guidelines (CG42) [January 3, 2016];Dementia: Supporting people with dementia and their carers in health and social care. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg42/chapter/1-guidance#interventions-for-cognitive-symptoms-and-maintenance-of-function-for-people-with-dementia.

- 21.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission [January 3, 2016];A data book: health care spending and the Medicare program. 2013 Available at: http://www.medpac.gov/documents/publications/jun14databookentirereport.pdf.

- 22.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services [January 3, 2016];Part D Program Analysis. 2013 Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Prescription-Drug-Coverage/PrescriptionDrugCovGenIn/ProgramReports.html.

- 23.Hargrave E, Hoadley J, Merrell K, et al. [January 3, 2016];Medicare Part D 2008 Data Spotlight: Ten most common brandSname drugs. 2008 94025(650) Available at: http://kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/medicare-part-d-2008-data-spotlight-ten. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deudon A, Maubourguet N, Gervais X, et al. Non-pharmacological management of behavioural symptoms in nursing homes. 2009 Apr;:1386–1395. doi: 10.1002/gps.2275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Callahan CM, Boustani MA, Unverzagt FW, et al. Effectiveness of collaborative care for older adults with Alzheimer disease in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 295(18):2148–2157. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.18.2148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fowler NR, Chen Y-F, Thurton CA, et al. The impact of Medicare prescription drug coverage on the use of antidementia drugs. BMC Geriatr. 2013;13(1):37. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-13-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gill S, Bronskill S, Normand S-LT, et al. Antipsychotic drug use and mortality in older adults with dementia. Ann Intern Med. 2007;(146):775–786. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-11-200706050-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schneider LS, Dagerman KS, Insel P. Risk of death with atypical antipsychotic drug treatment for dementia. JAMA. 2005;294(15) doi: 10.1001/jama.294.15.1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.FDA - U.S. Food and Drug Administration [January 3, 2016];FDA Alert. Information for healthcare professionals: contventional antipsychotics. 2005 Available at: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm124830.htm.

- 30.FDA - U.S. Food and Drug Administration Public Health Adivsory. Deaths with antipsychotics in elderly patients with behavioral distrubances. 2008 Available at: http://www.fda.gov/drugs/drugsafety/postmarketdrugsafetyinformationforpatientsandproviders/drugsafetyinformationforheathcareprofessionals/publichealthadvisories/ucm053171.htm.

- 31.Parsons C, Hughes CM, Passmore AP, et al. Withholding, discontinuing and withdrawing medications in dementia patients at the end of life: A neglected problem in the disadvantaged dying? Drugs and Aging. 2010;27(6):435–449. doi: 10.2165/11536760-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Newcomer R, Clay T, Luxenberg JS, et al. Misclassification and selection bias when identifying Alzheimer's disease solely from Medicare claims records. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47(2):215–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb04580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taylor DH, Fillenbaum GG, Ezell ME. The accuracy of medicare claims data in identifying Alzheimer's disease. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55(9):929–37. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(02)00452-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pressley J. Dementia in community-dwelling elderly patients: A comparison of survey data, medicare claims, cognitive screening, reported symptoms, and activity limitations. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56(9):896–905. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(03)00133-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taylor DH, Østbye T, Langa KM, et al. The accuracy of Medicare claims as an epidemiological tool: the case of dementia revisited. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;17(4):807–15. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ostbye T, Taylor DH, Clipp EC, et al. Identification of Dementia: Agreement among National Survey Data, Medicare Claims, and Death Certificates. Health Serv Res. 2008;43(1 Pt 1):313–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00748.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Hout H, Vernooij-Dassen M, Poels P, et al. Are general practitioners able to accurately diagnose dementia and identify Alzheimer's disease? A comparison with an outpatient memory clinic. Br J Gen Pract. 2000;50(453):311–312. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arevalo-Rodriguez I, Segura O, Solà I, et al. Diagnostic tools for Alzheimer's Disease dementia and other dementias: an overview of diagnostic test accuracy (DTA) systematic reviews. BMC Neurol. 2014;14(1):183. doi: 10.1186/s12883-014-0183-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koepsell TD, Gill DP, Chen B. Stability of Clinical Etiologic Diagnosis in Dementia and Mild Cognitive Impairment: Results From a Multicenter Longitudinal Database. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2013;28(8):750–758. doi: 10.1177/1533317513504611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lopez OL, Litvan I, Catt KE, et al. Accuracy of four clinical diagnostic criteria for the diagnosis of neurodegenerative dementias. Neurology. 1999;53(61292) doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.6.1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lexi-Data Basic database (Lexicomp) Cerner Multum; Denver: [January 3, 2016]. Available at: http://www.lexi.com/businesses/solutions/clinicaldecision-support. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chron Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Deyo R, Cherkin D, Ciol M. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):613–619. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zou G. A Modified Poisson Regression Approach to Prospective Studies with Binary Data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(7):702–706. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Beers MH, Ouslander JG, Rollingher I, et al. Explicit criteria for determining inappropriate medication use in nursing home residents. UCLA Division of Geriatric Medicine. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151(9):1825–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Beers MH. Explicit criteria for determining potentially inappropriate medication use by the elderly. An update. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(14):1531–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fick DM, Semla TP. 2012 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria: new year, new criteria, new perspective. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(4):614–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Howard RJ, Juszczak E, Ballard CG, et al. Donepezil for the treatment of agitation in Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1382–1392. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fox C, Crugel M, Maidment I, et al. Efficacy of memantine for agitation in Alzheimer's dementia: A randomised double-blind placebo controlled trial. PLoS One. 2012;7(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Johnell K, Weitoft GR, Fastbom J. Education and use of dementia drugs: a register-based study of over 600,000 older people. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2008;25(1):54–9. doi: 10.1159/000111534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Avila-Castells P, Garre-Olmo J, Calvó-Perxas L, et al. Drug use in patients with dementia: a register-based study in the health region of Girona (Catalonia/Spain). Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;69(5):1047–56. doi: 10.1007/s00228-012-1451-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Van den Bussche H, Kaduszkiewicz H, Koller D, et al. Antidementia drug prescription sources and patterns after the diagnosis of dementia in Germany: results of a claims data-based 1-year follow-up. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;26(4):225–31. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0b013e328344c600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Martinez C, Jones RW, Rietbrock S. Trends in the prevalence of antipsychotic drug use among patients with Alzheimer's disease and other dementias including those treated with antidementia drugs in the community in the UK: a cohort study. BMJ Open. 2013;3(1) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hoffmann F, van den Bussche H, Wiese B, et al. Impact of geriatric comorbidity and polypharmacy on cholinesterase inhibitors prescribing in dementia. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11(1):190. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-11-190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tjia J, Briesacher BA, Peterson D, et al. Use of medications of questionable benefit in advanced dementia. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(11):1763–71. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zuckerman IH, Ryder PT, Simoni-Wastila L, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in the treatment of dementia among Medicare beneficiaries. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2008;63(5):S328–33. doi: 10.1093/geronb/63.5.s328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wilson RS, Weir DR, Leurgans SE, et al. Sources of variability in estimates of the prevalence of Alzheimer's disease in the United States. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(1):74–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Munson J, Morden N, Goodman D, et al. [January 3, 2016];The Dartmouth Atlas of Medicare Prescription Drug Use. 2013 Available at: http://www.dartmouthatlas.org/downloads/reports/Prescription_Drug_Atlas_101513.pdf. [PubMed]

- 59.Koller D, Bynum JP. Dementia in the USA: state variation in prevalence. J Public Health (Oxf) 2014 doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdu080. epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wennberg J, Fisher E, Skinner J. Geography and the debate over Medicare reform. Health Aff. 2002;(Suppl Web Exclusives):W96–114. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w2.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chandra A, Skinner J. Technology growth and expenditure growth in health care. 2011 NBER Work Pap 16953. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mehta KM, Yaffe K, Pérez-Stable EJ, et al. Race/ethnic differences in AD survival in US Alzheimer's Disease Centers. Neurology. 2008;70(14):1163–70. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000285287.99923.3c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Luck T, Luppa M, Weber S, et al. Time until institutionalization in incident dementia cases--results of the Leipzig Longitudinal Study of the Aged (LEILA 75+). Neuroepidemiology. 2008;31(2):100–8. doi: 10.1159/000146251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yaffe K, Fox P, Newcomer R, et al. Patient and caregiver characteristics and nursing home placement in patients with dementia. JAMA. 2002;287(16):2090–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.16.2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mitchell AJ, Meader N, Pentzek M. Clinical recognition of dementia and cognitive impairment in primary care: a meta-analysis of physician accuracy. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2011;124(3):165–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01730.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Valcour VG, Masaki KH, Curb JD, et al. The detection of dementia in the primary care setting. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(19):2964–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.19.2964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.CMS. Partnership to Improve Dementia Care in Nursing Homes Antipsychotic Drug use in Nursing Homes Trend Update. 2014:5–8. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Iliffe S, Robinson L. Primary care and dementia: 1. diagnosis, screening and disclosure. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009 Nov;:895–901. doi: 10.1002/gps.2204. 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Boustani M, Callahan CM, Unverzagt FW, et al. Implementing a screening and diagnosis program for dementia in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(7):572–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0126.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Boustani MA, Schubert C, Sennour Y. The challenge of supporting care for dementia in primary care. Clin Interv Aging. 2007;2(4):631–6. doi: 10.2147/cia.s1802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]