ABSTRACT

Background:

Lack of knowledge, attitude and practice are some of the barriers of having a healthy lifestyle and controlling high blood pressure. This study aimed to determine the effectiveness of a lifestyle modification program on knowledge, attitude and practice of hypertensive patients with angioplasty.

Methods:

This study was a randomized controlled clinical trial conducted from November to April 2014 on 60 hypertensive patients with angioplasty in Shahid Chamran hospital of Isfahan, Iran. The samples were randomly assigned to two equal groups. Data collection was performed in three stages by a researcher-made questionnaire. The intervention plan was 6 education sessions and then follow up were done by phone call. The gathered data were analyzed via SPSS (V.20), using t-test, Chi-square, repeated measurement, and post hoc LSD test and ANOVA statistics.

Results:

The mean score of knowledge, attitude and practice in the experimental group immediately after the intervention was 77.8±7.2, 88.3±6.4 and 86.2±6.5, respectively and one month after the intervention was 80.8±7.4, 91.1±3.5 and 92.5±2.2, respectively. But in the control group, the mean score of knowledge, attitude and practice immediately after the intervention (34.90±11.23, 61.11±6.28, and 38.64±7.15) and one month after the intervention was (38.64±7.15, 59.56±6.31 and 37.27±7.26.

Conclusion:

Lifestyle modification program can be effective in promoting the knowledge, attitude and practice of hypertensive patients with angioplasty. Nurses can use this program in their care provision programs for these patients.

Trial Registration Number:IRCT2015062420912N3

KEYWORDS: Attitude, Hypertension, Knowledge, Lifestyle, Practice

INTRODUCTION

Cardiovascular diseases are the most common cause of death in the world which kills about 17.3 million people each year.1 The coronary artery diseases are the most chronic and life- threatening diseases.2 High blood pressure that is one of its main side effects and risk factors is responsible for 13% of deaths and 7% of inabilities.3 This disease would cause the highest rate of death, recurrence of heart problems and infections after treatments for coronary artery diseases including angioplasty.2 Therefore, it is necessary to perform appropriate interventions to control blood pressure, especially in patients undergoing angioplasty.

Based on Seven Joint National Committee Criteria (NJC7), the algorithm for treatment of hypertension begins with lifestyle modifications and ends with medication diets. Unfortunately, they didn’t receive proper education about lifestyle modification.4

Studies on lifestyle modifications have revealed that modifications such as weight loss, taking Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet, reducing salt consumption and exercising would be effective in lowering blood pressure and reducing its complications5,6 especially the rate of morbidity and mortality in hypertensive patients undergoing angioplasty.7

Different studies have been conducted on lifestyle modification programs and educational interventions for patients with high blood pressure. Despite the effectiveness of educational interventions on the lifestyle of patients with high blood pressure,8-12 the results of one study showed that educational interventions had no significant effect on weight, blood pressure level and physical activity in people at the risk of ischemic heart diseases.13 In another study, although health education improved the knowledge of patients with high blood pressure, it had no significant effect on the level of their blood pressure.14 Another study found no significant effect from educational interventions on blood pressure15 and another one found no significant relationship between weight changes and changes in diastolic blood pressure.16

Studies showed that ignorance and lack of knowledge and awareness are some of the barriers to having a healthy lifestyle and not controlling and preventing high blood pressure.17,18 It is assumed that increased knowledge about the role of lifestyle in the occurrence of high blood pressure would cause people to start modifying their lifestyles and enhance their preventive behaviors.19 The results of a study showed that when the score of knowledge in high blood pressure patients increases by one, their score of practice would increase by 0.12.20

Anyway, studies have shown that improving knowledge and awareness could not be enough to control the effects of diseases by itself. The results of the study showed that by increasing the score of attitude toward high blood pressure, systolic and diastolic blood pressures would decrease significantly.21 Also, the lack of motivation to modify the lifestyle is another barrier to control blood pressure,22 because people do not feel any necessity to change their lifestyle17,23 Some of the reasons leading to lack of motivation are not taking treatment and controlling high blood pressure seriously,18,24,25 alcohol consumption,26 unemployment, using smuggled drugs, drugs’ cost, health care, drugs’ side effects, and the complexity of diet for controlling blood pressure.22

However, just knowledge and attitude are not enough for lifestyle modifications. The results of studies showed that from those samples that had a good knowledge and attitude about exercise and healthy nutrition to prevent cardiovascular diseases, only 23.6% in the field of exercise and 24.1% in the field of nutrition showed a good practice.27,28 Results of the study showed that although educational lifestyle interventions improved the knowledge of the participants of the experimental group, it made no significant difference in the attitude and practice of the experimental group.

Also, most of the patients with high blood pressure assume themselves to be healthy until they start to show complication. They tend to change their lifestyle when their disease is advanced or they have started to experience serious complications such as coronary artery diseases29 and they feel the need to change their lifestyle when they have to go through coronary angioplasty.

Some patients with hypertension have no symptoms even without medication, but they would experience side effects after drug consumption.30 For these people, modification of lifestyle is useless; especially in high blood pressure patients who feel better after angioplasty and their health condition is improving, this matter is of greater importance, because when patients continue their previous unhealthy lifestyle, they would provide the ground for recurrence of their disease, so modification of attitude is necessary for changing their behaviors. Meanwhile, nurses, as the greatest health profession group31 that have the closest communication with patients in health environments, compared to other members of the health care team, have a more comprehensive understanding of these patients’ educational needs and they are more able to follow them up, manage their blood pressure7,32 and modify their lifestyle.

Considering the serious threat of this silent killer and the importance of healthy lifestyle to control it,5,6 the relationship between people’s knowledge, attitude and practice with improvement of healthy behaviors,19 and also the incremental growth of the prevalence of this disease and its complications and the low number of studies that have been conducted in Iran, we decided to conduct this study. The present study was conducted to evaluate the effect of an educational program to modify the lifestyle on knowledge, attitude and practice of hypertensive patients undergoing angioplasty.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was a randomized controlled clinical trial conducted from November to April 2014 in the critical care unit of The Shahid Chamran Hospital of Isfahan, Iran. Inclusions criteria were having a history of systolic pressure of 140 mmHg or more and diastolic pressure of 90 mmHg or more, having undergone coronary angioplasty, having appropriate clinical condition as confirmed by expert physician, being more than 40 years old, and being literate. The exclusion criteria were experiencing acute and severe stress during the study, experiencing intense changes in blood pressure so that the doctor would have to change the dose of consumed drugs, being on any special weight gain or weight loss diet, participating in systemic educational program to control blood pressure, having any limitations to do the interventions, and being absent more than 2 of the educational sessions.

The sample size was calculated using information from similar studies,8 assuming the confidence interval to be 95% (Z1) and the power of test to be 80% (Z2) and considering the minimum difference in mean changes of the scores of knowledge, attitude and practice between both groups to be “0.8 S” and researchers’ prediction to decline 30% of the sample to be 30 participants in each group.

Z1=1.96, Z2=0.84, d=0.8 S

In order to select the participants, we used table of random numbers; by moving along the table as many odd and even numbers and the number of participants was selected and then put in a block. After the participants were selected based on the inclusion criteria and through convenience sampling, then a numbered cart was opened for each one of them and dependent on the number, whether it was odd or even, the participants were allocated to any of the two groups of control and experimental. So, sample allocation continued until the sample size reached the predetermined number.

For this study, data were collected by reviewing medical records and a questionnaire. In addition, systolic and diastolic blood pressures, pulse rate, height and weight of both groups were measured for matching. This questionnaire was made by researchers and completed by the researcher’s assistant (the researcher and patients were familiar with the course of the study but the researcher’s assistant was not). The questionnaire consisted of two parts. The first part included information about disease and background variables (including age, sex, height, weight, blood pressure, pulse rate, education, marital status, and job) and the second part included questions to assess the knowledge, attitude and practice of the samples. This questionnaire was designed using opinions of professors, articles and texts.8,11,22,23,29

To determine the content validity of the questionnaire, it was given to 10 academic members of Nursing and Midwifery Faculty and Hypertension Research Center in Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. Modifications were made on the basis of recommendations and suggestions of the experts. After consulting with a statistician, the final questionnaire was modified. The questionnaire was valid for hypertensive patients. Reliability of this questionnaire was filled by 50 individuals who had the inclusion criteria and then based on the obtained scores the correlation coefficient was calculated. The Chronbach’s α for knowledge assessment was 0.860, for attitude assessment it was 0.748 and for practice assessment it was 0.771, which could confirm the questionnaire’s validity. In addition, test-retest method was used to determine the reliability of the questionnaire, so 20 patients with the inclusion criteria filled the questionnaire twice with 2 week interval; also, Pearson correlation coefficient for knowledge assessment was 0.822, for attitude assessment it was 0.812 and for practice assessment it was 0.782.

Each question in the questionnaire was scored separately and the total score was 100. So, each participant could get a total score between 0 and 100. T he knowledge-assessment questionnaire had 17 closed-answer 4-chioce questions; each correct answer was scored 1 and incorrect answer 0. Thus, each participant could get a total score between 0 and 17 in the knowledge dimension and for better understanding of the score it was calculated on the basis of 100; therefore, each participant could have a score of 100/17. The attitude-assessment questionnaire contained 21 questions that was scored based on 5-point Likert scale (completely agreed, agreed, no idea, disagreed and completely disagreed). Each question was scored from 0 to 4. So, each participant could get a total score between 0 and 84 in the dimension of attitude. At the end, the total score out of 100 was calculated so each participant’s score could be 100/84. The practice-assessment questionnaire had 27 questions that were also scored based on 5-point Likert scale (always, often, sometimes, rarely and never) to evaluate the patients’ practice regarding their lifestyle. Each question was scored from 0 to 4. Therefore, each participant could get a total score between 0 and 108 in the practice dimension. Finally, the total score out of 100 was calculated for better understanding of the score; hence, each participant could obtain a score of 100/108.

After sampling and taking written informed consent, the participants were assigned into two groups of experimental and control. Then, they completed the demographic, disease information and knowledge, attitude and practice questionnaire. Systolic and diastolic pressures of both groups were measured using a mercury sphygmomanometer from the right hand in sitting position, considering all the scientific principles. The participants’ height and weight were measured using a meter and calibrated scale.

The experimental group was divided into two groups of 8 and two groups of 7 persons and they were coordinated for group educational sessions. Also, to remind them, the researcher contacted each participant on the phone the day before each session. Based on previous study6,23 educational program was conducted in 6 sessions during 3 weeks, each lasting 45 to 60 minutes (table 1) and then follow-up was done weekly by phone calls for 4 weeks, each lasting 10 to 15 minutes.

Table 1.

Educational content of the experimental group

| Sessions | Educational content |

|---|---|

| First session | Definition of high blood pressure, sorting and diagnosing high blood pressure, number of follow ups and referring to the physician, complications and risk factors of high blood pressure and methods of treating and controlling high blood pressure |

| Second session | “DASH” diet, the importance of diet and its effect on controlling blood pressure, foods that could lower blood pressure, foods that could increase blood pressure, right method of cooking foods and its importance, the advantages of low salt and “DASH” diets |

| Third session | Appropriate duration, repetition and type of exercise for participants, the importance of increasing physical activity, inappropriate exercises, how to lose weight and its effect on controlling blood pressure, the risks of weight gain, the effect of increase in waist, abdomen and hip size on blood pressure, the advantages of increase in physical activity |

| Fourth session | The importance of regular drug treatment, different types of blood pressure lowering drugs, drug interactions, the right consumption method of drugs based on their dose and timing and considering drug interactions, drugs’ side effects |

| At the end of this session a scenario about some patients who have experienced acute complications due to lack of control of their blood pressure was given to the participants and they were asked to study it before next sessions. | |

| Fifth session | Reviewing scenarios in groups, presenting a video about a patient with high blood pressure, methods to defy stress, the advantages of stress management, the effect of stress and tension on blood pressure, relaxation and muscle releasing methods |

| Sixth session | Family’s participation was demanded to support patients, participants’ families were invited to participate in the last session, then they were informed shortly about the disease, healthy lifestyle, the ways to control it, the complications of not controlling the disease and the role of family’s participation in supporting the patient; at the end, a question and answer session was conducted with participants and their families |

| Phone follow up | Reviewing topics, obstacles, helping participants to remove the obstacles, answering participants’ questions, giving encouraging feedback |

This lifestyle modification program included all the aspects of lifestyle (hypertension, its complications and risk factors, losing weight if being overweight or obese, limiting alcohol intake, increasing physical activity, controlling stress, reducing salt intake and stopping smoking, using proper diet and medication) in three contexts of the patients’ knowledge, attitude and practice with participation and support of the patients’ family. We applied different educational methods including speeches, questions and answers, group discussion, reviewing scenarios, videos and educational booklets.

For the control group, two discussion sessions about the participants’ experiences of high blood pressure, diet, exercise and weight loss were conducted and then one month after the end of the study an educational session as questions and answers were conducted and educational booklets were given to the participants.

The post-test was peformed right after the end of the sessions and the final test was done one month after the sessions for both groups.

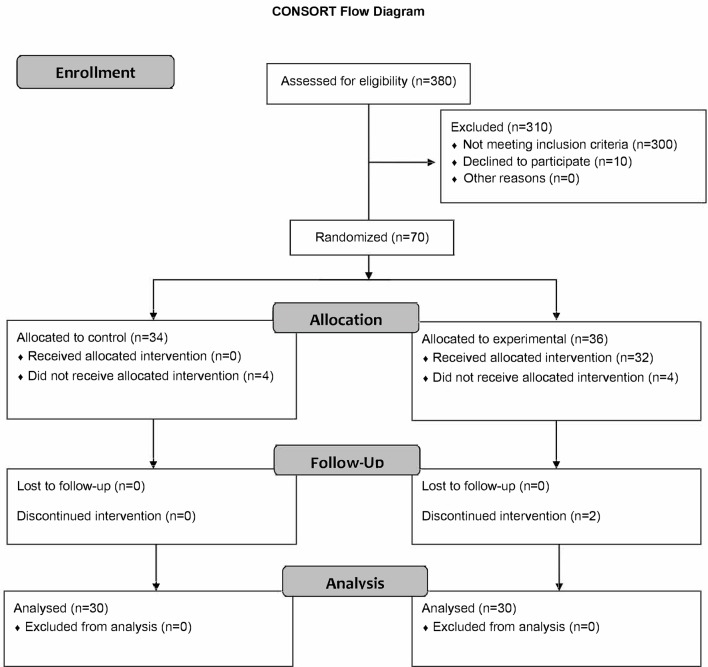

All the participants were given verbal and written information about the goals of the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients and they were free to withdraw from the study at any time. The ethics committee of the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences approved this study under project number 393679. The Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT) registered the study with the reference number IRCT (figure 1).

Figure1.

CONSORT flow diagram of the participants

Data were analyzed using independent t-test, paired t-test, Chi-square, repeated measurement, and post hoc LSD test and ANOVA with confidence interval of 95% through SPSS, version 20.

RESULTS

70 patients with high blood pressure who had undergone angioplasty entered this study and from them 10 withdrew due to unwillingness to continue the study (8 participants), experiencing severe stress (1 participant), and being hospitalized during the study (1 participant); at the end, 30 participants were assigned to each group and their data were analyzed.

The results of the study showed that participants of both groups were statistically similar regarding their age, height, weight, BMI, sex, marital status, education, duration of having high blood pressure, systolic pressure, diastolic pressure, and pulse (table 2). It must be mentioned that all of the participants in both groups were married; most of them were male (86%), freelancer with moderate economic status (56%), and had an educational level of literate (75%).

Table 2.

Comparison of the mean of demographic variables in the experimental and control groups

| Study variables | Groups study | Independent samples t-test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental (Mean±SD) | Control (Mean±SD) | T | P | |

| Age | 58.4±6.5 | 55.6±6.5 | 1.60 | 0.114 |

| Height | 169.3±7.9 | 166.2±8.8 | 1.43 | 0.159 |

| Weight | 79.2±9.5 | 78.8±7.1 | 0.17 | 0.866 |

| BMI | 27.6±3.1 | 28.7±3.5 | 1.21 | 0.231 |

| Duration of having hypertension | 3.5±3.4 | 3.3±3.1 | 0.22 | 0.820 |

| Systolic blood pressure | 144.4±18.1 | 142.5±15.2 | 0.42 | 0.673 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | 84.3±9.0 | 84.9±10.7 | 0.23 | 0.815 |

| Pulse | 81.9±3.4 | 83.3±3.1 | 0.22 | 0.820 |

Independent t-test showed that the mean score of knowledge (P=0.45), attitude (P=0.33) and practice (P=0.31) in both the control and experimental groups before the study had no significant difference and both groups were statistically similar (P>0.05). The results of the study showed that the mean score of knowledge (P=0.800), attitude (P=0.160) and practice (P=0.190) of the control group right after the study and one month later had no significant difference, but ANOVA analysis with repeated observations showed a significant difference between the mean score of knowledge, attitude and practice of the experimental group right after the study and one month later (P<0.0001; table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of the mean (standard deviation) score of Knowledge, Attitude & Practice in the experimental and control groups in three time periods

| Study variables | Time | Before the intervention | Immediately after the intervention | One month after the intervention | ANOVA test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Mean±SD | Mean±SD | Mean±SD | F | P | |

| Knowledge | Experimental | 31.4±15.4 | 77.8±7.2 | 80.8±7.4 | 147.90 | <0.001 |

| Control | 34.21±13.3 | 34.90±11.2 | 35.88±10.01 | 0.22 | 0.800 | |

| Attitude | Experimental | 59.9±7.7 | 88.3±6.4 | 91.1±3.5 | 177.60 | <0.001 |

| Control | 61.59±7.4 | 61.11±6.3 | 59.56±6.3 | 1.97 | 0.160 | |

| Practice | Experimental | 35.5±10.5 | 86.2±6.5 | 92.5±2.2 | 500.30 | <0.001 |

| Control | 37.99±8.2 | 38.64±7.1 | 37.27±7.2 | 0.74 | 0.190 | |

Also, in the experimental group the post hoc LSD test showed that the mean score of knowledge and attitude right after the study and one month later was significantly higher than those of knowledge and attitude before the study (P=0.001); however, the mean score of knowledge (P=0.160) and attitude (P=0.070) right after the study and one month later showed no significant difference. The mean score of practice right after the study and one month later had a significant difference with the mean score of practice before the study and also the mean score of practice right after the study and one month later showed a significant difference (P=0.001).

Independent t-test showed that the means of change score of knowledge, attitude and practice between both groups of control and intervention right after the study and one month later had a significant difference (P<0.001), meaning that the mean score of knowledge, attitude and practice of the experimental group right after the study and one month later was significantly higher than that of the control group (P<0.001).

DISCUSSION

The results of the present study showed that this educational lifestyle modification program has been effective on knowledge, attitude and practice of patients with high blood pressure who had undergone angioplasty. Comparison of demographic data and disease information of both control and experimental groups before the study revealed that participants of both groups were statistically similar.

The results showed no significant difference between the mean score of knowledge, attitude and practice between the two groups before the study. The mean score of knowledge, attitude and practice of the experimental group right after the study and one month later was significantly higher than that of the control group and it seems that the lifestyle modification program has been effective. In this regard, the results of study showed that the mean score of knowledge, attitude and practice of the experimental group three months after the study had a significant difference with that of the control group.10 But the results showed that although the mean score of attitude and behavior of the experimental group three months after the study had a significant difference with that of the control group, the mean score of knowledge showed no significant difference between both groups three months after the study.34

The results of the present study showed an increase in the mean score of knowledge in the experimental group after the study. In this regard, the results of the study showed that the mean score of knowledge of patients increased and following the “DASH” diet lowered the patients’ blood pressure.8 The significant improvement of knowledge in the experimental group is very valuable and important, because having knowledge about healthy lifestyle is considered a prerequisite and necessity for having the right attitude and appropriate practice.28 These changes could indicate the significant effect of multilateral lifestyle interventions on improvement of the patients’ knowledge.

The results of the present study showed that the mean score of attitude of the experimental group increased right after the study. In this regard, the results of the study that aimed to evaluate the effect of health education on knowledge and attitude of patients with high blood pressure about how to take care of themselves showed that the mean score of attitude was significantly increased in patients.35 The results of the study showed that by increasing the mean score of attitude toward high blood pressure, systolic and diastolic pressures were significantly lowered.21 In the present study, the intervention program was effective on enhancing the attitude of patients toward modifying their lifestyle and it has created a background for patients to change their practice.

In contrast to the above-mentioned results, the findings of a study showed that although educational lifestyle modification improved the knowledge of the participants of the experimental group, it caused no significant difference in their attitude.36 Also, the results of another study showed that educational interventions had no significant effect right after the study and 3 months later on the experimental groups’ attitude.37

In the present study, although the mean score of knowledge and attitude one month after the study had no significant difference with that of knowledge and attitude right after the study, it had an increase, showing the stability and increased durability of knowledge and attitude among the participants of the experimental group and the effectiveness of the lifestyle modification program.

The results of the present study showed that the mean score of practice significantly increased right after the study and one month later. Also, there was a significant difference between the mean score of practice right after the study and one month later. In this regard, the results of a study that aimed to determine the effect of education through booklet and brochure on the blood pressure of hypertension patients showed that lifestyle interventions through booklets would increase the mean score of knowledge, attitude and practice in patients with high blood pressure.10 Moreover, the result of another study on the effect of health education interventions (group sessions held during 12 months) showed that the interventions improved the knowledge, attitude and practice of patients with high blood pressure.11 Also, the results of study showed that lifestyle modification in patients with high blood pressure would lower their blood pressure during 3 and 6 months of follow up.38

Although the results of the present study were similar to those of previous studies, some of the important features of the present study were participation and support of the patients’ families, patient follow-up for one month, having the history of coronary angioplasty and also using a multilateral lifestyle modification program to improve knowledge, attitude and practice.

Unlike the results of the present study, the results of another study showed that although educational interventions improved the knowledge and attitude of the participants of the experimental group, it caused no significant difference in the practice of the experimental group.39 Also, another research revealed that despite improvement in knowledge, attitude and practice of diabetic patients, educational interventions had no significant effect on lifestyle and self-care. They believed this program was not effective.36 The results of the study showed that the change of the mean of practice about consumption of fruits and vegetables after the study was not significant between the control and experimental groups.40 Furthermore, the findings of a study showed that the participants’ practice about physical activity right after the study, 3 months later and 9 months later showed no significant difference between the control and experimental groups.28 In this regard, the results of an investigation in this field showed that educational lifestyle intervention had no significant effect on the participants’ weight, blood pressure and practice regarding physical activity.13

It seems that just having knowledge or a partial knowledge and awareness would not lead to a change in health behaviors, and practical application of knowledge and information requires enhancement of awareness through appropriate educational programs and changing the patients’ attitude and beliefs. Therefore, to make effective interventions, target groups must be defined and appropriate behavior changing strategies must be applied.27

The most important limitation of this study was the follow-up time, so it is recommended that future studies should be performed with longer follow-up periods.

CONCLUSION

Based on the results of the present study, this lifestyle modification program that was conducted using different educational methods including speeches, questions and answers, group discussion, reviewing scenarios, videos and educational booklets targeted all the aspects of lifestyle with participation and support of the patients’ families and following up patients with high blood pressure and angioplasty history, it can be an effective program to improve knowledge, attitude and practice of patients and it is recommended that nurses should use this program in their care providing programs for these patients.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We are thankful to the CCU personnel of Shahid Chamran Hospital and patients who participated in this study. We appreciate the grant from Nursing and Midwifery Care Research Center of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences for performing this study.

Conflict of Interest:None declared.

REFRENSES

- 1.Quan H, Chen G, Walker RL, et al. Incidence, cardiovascular complications and mortality of hypertension by sex and ethnicity. Heart. 2013;99:715–21. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2012-303152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Luca G, Dirksen MT, Spaulding C, et al. Impact of hypertension on clinical outcome in STEMI patients undergoing primary angioplasty with BMS or DES Insights from the DESERT cooperation. International Journal of Cardiology. 2014;175:50–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.04.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 Evidence-Based Guideline for the Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: Report From the Panel Members Appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8) Journal of American Medical Association (JAMA) 2014;311:507–20. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.284427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chiazor IE, Oparah A. Assessment of Hypertension Care in a Nigerian Hospital. Tropical Journal of Pharmaceutical Research. 2012;11:137–45. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ariff F, Suthahar A, Ramli M. Coping styles and lifestyle factors among hypertensive and non-hypertensive subjects. Singapore Medical Journal. 2011;52:29–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Svetkey LP, Pollak KI, Yancy WS Jr, et al. Hypertension Improvement Project Randomized Trial of Quality Improvement for Physicians and Lifestyle Modification for Patients. Hypertension. 2009;54:1226–33. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.134874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sadeghzadeh V, Raoufi Kelachayeh S, Naserian J, et al. The effect of self-care documented program on performance of patients undergoing coronary angioplasty. International Research Journal of Applied and Basic Sciences. 2013;4:86–90. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Babu A. Effectiveness of structured teaching program on knowledge of hypertensive patients regarding dash diet at selected community area, Bangalore . Bangalore, Karnataka (India): Rajiv Gandhi University of Health Science; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Webber J. The effect of a lifestyle modification adherence tool on risk factors in patients with chronic hypertension compared to usual management . Johannesburg (South Africa): The Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dawes MG, Kaczorowski J, Swanson G, et al. The effect of a patient education booklet and BP ‘tracker’ on knowledge about hypertension. A randomized controlled trial. Family Practice 2010;27:472–8. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmq048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mahajan H, Kazi Y, Sharma B, Velhal GD. Health Education: An Effective Intervention in Hypertensive Patients. International Journal of Recent Trends in Science and Technology. 2012;4:77–82. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li J, Zheng H, Du Hb, et al. The multiple lifestyle modification for patients with prehypertension and hypertension patients: a systematic review protocol. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e004920. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-004920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dekkers JC, van Wier MF, Ariëns GA, et al. Comparative effectiveness of lifestyle interventions on cardiovascular risk factors among a dutch overweight working population: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:49. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pandit AU, Tang JW, Bailey SC, et al. Education, literacy, and health: Mediating effects on hypertension knowledge and control. Journal of Patient Educ Couns. 2009;75:381–5. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reuther L, Paulsen MS, Anderson M, et al. Is a targeted intensive intervention effective for improvements in hypertension control? A randomized controlled trial. Family Practice 2012;29:626–32. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cms031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aucott L, Rothnie H, McIntyre L, et al. Long-Term Weight Loss From Lifestyle Intervention Benefits Blood Pressure? a systematic review. Hypertension. 2009;54:756–62. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.135178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Demaio AR, Otgontuya D, Courten M, et al. Hypertension and hypertension-related disease in Mongolia; findings of a national knowledge, attitudes and practices study. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:194. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kamran A, Azadbakht L, Sharifirad G, et al. Sodium Intake, Dietary Knowledge, and Illness Perceptions of Controlled and Uncontrolled Rural Hypertensive Patients. International Journal of Hypertension. Int J Hypertens 2014;2014:245480. doi: 10.1155/2014/245480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lyalomhe GBS, Lyalomhe SI. Hypertension-related knowledge, attitudes and life-style practices among hypertensive patients in a sub-urban Nigerian community. Journal of Public Health and Epidemiology. 2010;2:71–7. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Naeimi E, Malekzadeh J, Hadinia A, et al. Assessment of Knowledge and Practice of Hypertensive Patients in Boyer Ahmad Township in 2008. Armaghan Danesh. 2010;16:489–97. [In Persian] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Newell M, Modeste N, Marshak HH, Wilson C. Health beliefs and the prevention of hypertension in a black population living in London. Etnicity and Disease. 2009;19:35–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rakumakoe M. To determine the knowledge, attitude & perceptions of hypertensive patients towards lifestyle modification in controlling hypertension . Johannesburg: University of Witwatersrand; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dananagowda H. A study to assess the knowledge and attitude regarding life style modifications to prevent hypertension among bank employees in selected hypertension among bank employees in selected banks at Tumkur . India: Rajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gee ME, Bienek A, Campbell NR, et al. Prevalence of, and Barriers to, Preventive Lifestyle Behaviors in Hypertension (from a National Survey of Canadians with Hypertension) The American Journal of Cardiology. 2012; 109:570–5. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gersh BJ, Sliwa K, Mayosi BM, Yusuf S. The epidemic of cardiovascular disease in the developing world: global implications. European Heart Journal. 2010;31:642–8. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zungu LI, Djumbe FR. Knowledge and lifestyle practices of hypertensive patients attending a primary health care clinic in Botswana. UNISA. 2013:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jafari N, Avazeh A, Rabi-siahkali S, Mazloom zadeh S. Knowledge, attitude and practice of women about nutrition and exercise and its relation with risk factors for cardiovascular disease. The Scientific Journal of Zanjan University of Medical Sciences. 2010;18:50–60. [In Persian] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mc Eachan, R Lawton, R Jackon, C et, al Testing a workplace physical activity intervention: a cluster randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2011;8:29. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-8-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Song H, Kim SA, Park WS. Effects of a hypertension management program by Seongcheon primary health care post in South Korea: an analysis of changes in the level of knowledge of hypertension in the period from 2004 to 2009. Health Education Research. 2012;27:411–23. doi: 10.1093/her/cys012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Woods SL, Sivarajan Froelicher, ES Adams, Motzer S, Bridges EJ. Cardiac Nursing. 6th ed. China: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bastable SB. Nurse as educator: principles of teaching & learning for nursing practice. 2nd ed. USA: Jones & Bartlett; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 32.McClellan WM, Craxton LC. Improved follow-up care of hypertensive patients by a nurse practitioner in a rural clinic. The Journal of Rural Health. 1985;1:34–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.1985.tb00125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rocha-Goldberg Mdel, P Corsino, L Batch, B et, al Hypertension Improvement Project (HIP) Latino: results of a pilot study of lifestyle intervention for lowering blood pressure in Latino adults. Ethn Health. 2010;15:269–82. doi: 10.1080/13557851003674997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Amini N, Bayat F, Rahimi M, et al. Effect of Education on Knowledge, Attitude and Nutritional Behavior of patients with type 2 diabetes. Journal of Health & Development. 2013;1:306–14. [In Persian] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jalilian N, Tavafian S, Aghamolaei T, Ahmadi S. Educational Intervention on the Knowledge and Attitudes of People with Hypertension: A Clinical Trial. Quarterly Journal of Health Education and Health Promotion. 2014;1:37–44. [In Persian] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Palaian S, Acharya L, Rao PGM, et al. Knowledge, Attitude and practice outcomes: evaluating the impact of counseling in hospitalized diabetic patients in India. P&T Around the World. 2006;31:383–96. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shab bidar S, Fathi B. Effect of Nutritional Education on Knowledge, Attitude and Practice of type 2 diabetic patients. Journal of Birjand University of Medical Sciences. 2007;1:31–7. [In Persian] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schoenthaler A, Luerassi L, Teresi JA, et al. A practice-based trial of blood pressure control in African Americans (TLC-Clinic): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2011;12:265. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-12-265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mehran L, Nazeri P, Delshad H, et al. Does a text messaging intervention improve knowledge, attitudes and practice regarding iodine deficiency and iodized salt consumption? Journal of Public Health Nutrition. 2012;15:2320-5. doi: 10.1017/S1368980012000869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Manios Y, Moschois G, Katsaroil L, et al. Changes in diet quality score, macro- and micronutrients intake following a nutrition education intervention in postmenopausal women. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2007;20:126–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2007.00750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]