Abstract

Tertiary lymphoid structures (TLS) are ectopic lymphoid aggregates that reflect lymphoid neogenesis occurring in tissues at sites of inflammation. They are detected in tumors where they orchestrate local and systemic anti-tumor responses. A correlation has been found between high densities of TLS and prolonged patient’s survival in more than 10 different types of cancer. TLS can be regulated by the same set of chemokines and cytokines that orchestrate lymphoid organogenesis and by regulatory T cells. Thus, TLS offer a series of putative new targets that could be used to develop therapies aiming to increase the anti-tumor immune response.

Keywords: cancer, tertiary lymphoid structure, tumor microenvironment, chemokine, adaptive immune response

Introduction

Tertiary lymphoid structures (TLS) are transient ectopic lymphoid organizations that develop after birth in non-lymphoid tissues, in situations of chronic inflammation. They display an overall organization similar to that observed in canonical secondary lymphoid organs (SLOs), such as lymph nodes (LNs), with a T cell-rich area characterized by a T cell and mature DC-Lamp+ dendritic cell (DCs) cluster, a B-cell-rich area composed of a mantle of naïve B cells surrounding an active germinal center (GC) (1–3), the presence of high endothelial venules (HEVs), a particular type of blood vessels expressing peripheral node addressins (PNAd) and specialized in the extravasation of circulating immune cells, and the secretion of chemokines (CCL19, CCL21, CXCL10, CXCL12, and CXCL13) that are crucial for lymphocyte recruitment and entry into the LN (4–8). TLS have been detected in the tumor invasive margin and/or in the stroma of most cancers and their densities correlate with a favorable clinical outcome for the patients (Table 1). A series of studies performed by our group in non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) demonstrated that TLS are important sites for the initiation and/or maintenance of the local and systemic T- and B-cell responses against tumors, in accordance with a specific signature of genes related to T and B cell lineage, chemotaxis, Th1 polarization, lymphocyte activation, and effector function associated with TLS presence (Table 2). They represent a privileged area for the recruitment of lymphocytes into tumors and the generation of central-memory T and B cells that circulate and limit cancer progression (5, 9, 10).

Table 1.

Prognostic value of TLS in primary and metastatic tumors.

| Criteria | Cancer type | Stages of the disease | No. of patients | TLS detection IHC | TLS detection gene expression | Prognostic value | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary tumors | Breast carcinoma | I–III | 146 | PNAd | – | Positive | (8) |

| I–III | 146 | DC-Lamp | – | Positive | (11) | ||

| I–III | 794 | – | TFH, CXCL13 | Positive | (12) | ||

| Breast carcinoma (triple negative) | I–III | 769 | H&S | – | Positive | (13) | |

| Colorectal cancer | I–IV | 350 | H&S | – | Positive | (14) | |

| ND | 25 | DC-Lamp | – | Positive | (15) | ||

| I–IV | 40 | CD3, CD83 | – | Positive | (16) | ||

| II | 185 | CD3 | – | Positive | (17) | ||

| III | 166 | CD3 | – | No value | (17) | ||

| 0–IV-A | 21 | – | 12-chemokine genes | Positive | (3) | ||

| I–IV | 125 | – | CXCL13 and CD20 | Positive | (18) | ||

| Gastric cancer | All without chemo | 82 | CD20 | – | Positive | (19) | |

| I–III | 365 | – | both Th1 and B | Positive | (19) | ||

| NSCLC | I–II | 74 | DC-Lamp | – | Positive | (1) | |

| I–IV | 362 | DC-Lamp | – | Positive | (9) | ||

| III with neo-adj. chemo | 122 | DC-Lamp, CD20 | – | Positive | (2) | ||

| Melanoma | I-A–III-A | 82 | DC-Lamp | – | Positive | (20) | |

| IV | 21 | – | 12-chemokine genes | Positive | (21) | ||

| Oral SCC | All | 80 | CD3, CD20, CD21, BCL6, PNAd | – | Positive | (22) | |

| Pancreatic cancer | All | 308 + 226 | H&E | – | Positive | (23) | |

| RCC | All | 135 | DC-Lamp | – | Positive | (24) | |

| Hepatocellular Cancer | All | 82 | H&S | 11-chemokine genes | Negative | (25) | |

| Biliary tract cancer | All | 335 | CD20 (TMA) | – | No value | (26) | |

| Metastatic tumors | Colorectal cancer (liver) | All | 14 + 51 | CD20 | – | Positive | (27) |

| Colorectal cancer (lung) | ND | 140 | DC-Lamp | – | Positive | (15) |

Table 2.

Expression of genes associated with TLS presence in human cancers.

| Name of the gene | Main names of the protein | Main immune functions and process | Cluster of gene related to TLS presence | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCL2 | CCL2, MCP-1, MCAF | Monocyte, immature DC and T cell chemotaxis, G-protein-coupled receptor signaling pathway, cell adhesion, JAK-STAT cascade, MAPK cascade, cellular calcium ion homeostasis, cellular response to IFN-γ, IL-1, and IL-6 | Chemotaxis | (3) |

| CCL3 | CCL3, MIP-1α | Monocyte and T cell chemotaxis, G-protein-coupled receptor signaling pathway, cell adhesion, MAPK cascade, calcium-mediated signaling, cell activation, cellular response to IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-1, eosinophil degranulation, inflammatory response | Chemotaxis | (3) |

| CCL4 | CCL4, MIP-1β, LAG1 | Monocyte and neutrophil and T cell chemotaxis, G-protein-coupled receptor signaling pathway, cell adhesion, calcium-mediated signaling, cell activation, cellular response to IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-1, inflammatory response, positive regulation of ERK1 and ERK2 cascade, positive regulation of GTPase activity | Chemotaxis | (3) |

| CCL5 | CCL5, RANTES | Monocyte, neutrophil and T cell chemotaxis, G-protein-coupled receptor signaling pathway, calcium-mediated signaling, cellular response to IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-1, inflammatory response | Chemotaxis | (3, 9) |

| CCL8 | CCL8, MCP-2, HC14 | Monocyte, neutrophil and T cell chemotaxis, G-protein-coupled receptor signaling pathway, cellular response to IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-1, chronic inflammatory response, positive regulation of ERK1 and ERK2 cascade, positive regulation of GTPase activity, negative regulation of leukocyte proliferation | Chemotaxis | (3) |

| CCL17 | CCL17, TARC, ABCD-2 | Monocyte and T cell chemotaxis, G-protein-coupled receptor signaling pathway, cellular response to IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-1, inflammatory response, positive regulation of ERK1 and ERK2 cascade, positive regulation of GTPase activity | Chemotaxis/T cells | (5) |

| CCL18 | CCL18, PARC, MIP-4, AMAC-1, DC-CK1 | Monocyte, neutrophil and T cell chemotaxis, G-protein-coupled receptor signaling pathway, cellular response to IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-1, inflammatory response, positive regulation of ERK1 and ERK2 cascade, positive regulation of GTPase activity | Chemotaxis | (3) |

| CCL19 | CCL19, MIP-3β, ELC | Mature DC and T cell chemotaxis, G-protein-coupled receptor signaling pathway, T cell costimulation, cell maturation, cellular response to IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-1, inflammatory response, activation of JUN kinase activity, establishment of T cell polarity, immunological synapse formation, inflammatory response, positive regulation of IL-1β, IL-12, and TNF-α secretion, positive regulation of ERK1 ERK2 JNK cascade, response to PGE | Chemotaxis, chemotaxis/T cells | (3, 5) |

| CCL20 | MIP-3α, LARC, Exodus | Immature DC monocyte neutrophil and T cell chemotaxis, G-protein-coupled receptor signaling pathway, cellular response to IL-1, TNF-α, and LPS, inflammatory response, positive regulation of ERK1 and ERK2 cascade | Th1/B cells | (19) |

| CCL21 | CCL21, SLC, 6Ckine, TCA4 | Mature DC neutrophil and T cell chemotaxis, G-protein-coupled receptor signaling pathway, T cell costimulation, cell maturation, cellular response to IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-1, inflammatory response, cell maturation, establishment of T cell polarity, negative regulation of DC dendrite assembly, positive regulation of DC APC function, immunological synapse formation, inflammatory response, activation of GTPase activity, cellular response to IL-1 and TNF-α, positive regulation of ERK1 ERK2 JNK cascade, response to PGE | Chemotaxis, chemotaxis/T cells | (3, 5) |

| CCL22 | CCL22, MDC, ABCD-1, DC/B-CK | Monocyte and T cell chemotaxis, G-protein-coupled receptor signaling pathway, cellular response to IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-1, inflammatory response, positive regulation of ERK1 and ERK2 cascade, positive regulation of GTPase activity | Chemotaxis/T cells | (5) |

| CCR2 | CCR2, CD192, CC-CKR2 | Monocyte, immature DC and lymphocyte chemotaxis, G-protein-coupled receptor signaling pathway, positive regulation of inflammatory response, JAK–STAT cascade, negative regulation of eosinophil degranulation, positive regulation of Th1 immune response, negative regulation of Th2 immune response, positive regulation of IL-1β, IL-2, IL-6, and TNF production | Chemotaxis/Th1/cytotoxicity/activation | (9) |

| CCR4 | CCR4, CD194, ChemR13, CC-CKR4 | Monocyte and lymphocyte chemotaxis, G-protein-coupled receptor signaling pathway, inflammatory response, tolerance induction | Chemotaxis/Th1/cytotoxicity/activation | (9) |

| CCR5 | CCR5, CD195 | Myeloid and lymphocyte chemotaxis, G-protein-coupled receptor signaling pathway, inflammatory response, negative regulation of macrophage apoptotic process, positive regulation of IL-1, IL-6, and TNF production, co-receptor of HIV | Chemotaxis/Th1/cytotoxicity/activation, Th1/B cells | (9, 19) |

| CCR7 | CCR7, CD197, CMKBR7, CC-CKR7, BLR2, EBI1 | Monocyte mature DC and lymphocyte chemotaxis, G-protein-coupled receptor signaling pathway, inflammatory response, positive regulation of ERK1 and ERK2 cascade, positive regulation of GTPase activity, establishment of T cell polarity, negative thymic T cell selection, positive regulation of JNK cascade, positive regulation of T cell costimulation and TCR signaling pathway, positive regulation of APC function, positive regulation of humoral immunity, regulation of IFN-γ, IL-1β, and IL-12 production | Chemotaxis/Th1/cytotoxicity/activation | (9) |

| CD3e | CD3, TCRE, IMD18 | T cell activation and costimulation, TCR signaling pathway, negative thymic T cell selection, positive regulation of T cell proliferation and anergy, positive regulation of IFN-γ, IL-2, and IL-4 production | Chemotaxis/T cells, chemotaxis/Th1/cytotoxicity/activation | (5, 9) |

| CD4 | CD4 | T cell activation, T cell differentiation, T cell selection, cytokine production | Chemotaxis/Th1/cytotoxicity/activation, Th1/B cells | (9, 19) |

| CD5 | CD5, LEU1 | T cell costimulation, apoptotic signaling pathway, cell proliferation, cell recognition, receptor-mediated endocytosis | Th1/B cells | (19) |

| CD8A | CD8A, Leu2, p32 | T cell activation, T cell-mediated immunity, cell surface receptor signaling pathway, cytotoxic T cell differentiation, defense response to virus | Chemotaxis/Th1/cytotoxicity/activation | (9) |

| CD19 | CD19, B4, CVID3 | B-cell receptor signaling pathway, cell surface receptor signaling pathway, cellular defense response, phosphatidylinositol-mediated signaling, regulation of immune response | Chemotaxis/Th1/cytotoxicity/activation | (9) |

| CD20 | CD20, MS4A1, LEU-16 | B-cell lineage, B-cell proliferation, humoral immune response | Th1/B cells | (18, 19) |

| CD28 | CD28, Tp44 | T cell costimulation, TCR signaling pathway, negative thymic T cell selection, positive regulation of T cell proliferation, positive regulation of IL-2, IL-4, and IL-10 production, immunological synapse, positive regulation of isotype switching to IgG, humoral immune response | Chemotaxis/Th1/cytotoxicity/activation | (9) |

| CD38 | CD38, ADPRC1 | T cell activation, positive regulation of B-cell proliferation, B-cell receptor signaling pathway, negative regulation of apoptotic process, cell adhesion, calcium signaling, response to IL-1 | Chemotaxis/Th1/cytotoxicity/activation, Th1/B cells | (9, 19) |

| CD40 | CD40, TNFRSF5 | B-cell proliferation, inflammatory response, positive regulation of B-cell proliferation, positive regulation of MAP kinase activity, positive regulation of IL-12 production, positive regulation of isotype switching to IgG, regulation of Ig secretion, TNF-mediated signaling pathway | Chemotaxis/Th1/cytotoxicity/activation, Th1/B cells | (9, 19) |

| CD40L | CD40 ligand, TRAP, CD154, HIGM1, TNFSF5, IGM | B-cell differentiation and proliferation, T cell costimulation, Ig secretion, isotype switching, negative regulation of apoptotic process, inflammatory response, positive regulation of NF-kappaB transcription factor activity, positive regulation of T cell proliferation, positive regulation of IL-4, IL-10, and IL-12 production, TNF-mediated signaling pathway | Chemotaxis/Th1/cytotoxicity/activation | (9) |

| CD62L | CD62L, L-selectin, LECAM1, LAM1 | Cell adhesion, leukocyte migration, regulation of immune response | Chemotaxis/Th1/cytotoxicity/activation | (9) |

| CD68 | CD68, LAMP4, GP110, SCARD1 | Cellular response to organic substance | Chemotaxis/Th1/cytotoxicity/activation | (9) |

| CD80 | CD80, B7, BB1, B7-1, CD28LG1 | T cell activation, T cell costimulation, intracellular signal transduction, phosphatidylinositol-mediated signaling, positive regulation of Th1 cell differentiation, positive regulation of αβT cell proliferation, positive regulation of IL-2 | Chemotaxis/Th1/cytotoxicity/activation | (9) |

| CD86 | CD86, B7-2, B70, CD28LG2 | B and T cell activation, T cell costimulation, cellular response to cytokine stimulus, DC activation, negative regulation of T cell anergy, phosphatidylinositol-mediated signaling, positive regulation of Th2 differentiation and T cell proliferation, positive regulation of IL-2 and IL-4 biosynthetic process, positive regulation of transcription and DNA-templated, response to IFN-γ, TLR3 signaling pathway | Chemotaxis/Th1/cytotoxicity/activation | (9) |

| CD200 | CD200, OX-2 | Regulation of immune response, negative regulation of macrophage activation, cell recognition | Tfh cells | (12) |

| CSF2 | CSF2, GM-CSF | DC differentiation, macrophage activation, MAPK cascade, negative regulation of cytolysis, positive regulation of cell proliferation, positive regulation of IL-23 production, positive regulation of gene expression | Th1/B cells | (19) |

| CTLA-4 | CTLA-4, CD152, IDDM12, ALPS5, GSE | T cell costimulation, negative regulation of Treg differentiation, negative regulator of B-cell proliferation, B-cell receptor signaling pathway, positive regulation of apoptotic process | Chemotaxis/Th1/cytotoxicity/activation | (9) |

| CXCL9 | CXCL9, MIG, CMK | Neutrophil and T cell chemotaxis, Th1 polarization, G-protein-coupled receptor signaling pathway, inflammatory response, regulation of cell proliferation | Chemotaxis, Th1 orientation | (3) |

| CXCL10 | CXCL10, IP10 | Neutrophil monocyte and T cell chemotaxis, Th1 polarization, G-protein-coupled receptor signaling pathway, inflammatory response, positive regulation of cell proliferation | Chemotaxis, chemotaxis/Th1/cytotoxicity/activation | (3, 9) |

| CXCL11 | CXCL11, IP9, I-TAC | T cell chemotaxis, Th1 polarization, G-protein-coupled receptor signaling pathway, inflammatory response, positive regulation of cell proliferation | Chemotaxis, chemotaxis/Th1/cytotoxicity/activation | (3, 9) |

| CXCL13 | CXCL13, BLC, BCA1, SCYB13 | B and Tfh cell chemotaxis, germinal center formation, lymph node development, regulation of humoral immunity, regulation of cell proliferation | Chemotaxis, chemotaxis/T cells, Tfh cells | (3, 5, 12, 18, 19) |

| CXCR3 | CXCR3, CD182, CD183, GPR9 | Neutrophil and T cell chemotaxis, Th1 polarization, G-protein-coupled receptor signaling pathway, inflammatory response, apoptotic process, cell adhesion, calcium-mediated signaling | Chemotaxis/Th1/cytotoxicity/activation | (9) |

| FasLG | Fas ligand, FASL, APTL, CD178, CD95L, TNFSF6, TNLG1A | T cell apoptotic process, activation of cysteine-type endopeptidase activity involved in apoptotic process, inflammatory cell apoptotic process, necroptotic signaling pathway, positive regulation of I-kappaB kinase/NK-kappaB signaling, positive regulation of cell proliferation, response to growth factor, transcription and DNA-templated | Chemotaxis/Th1/cytotoxicity/activation | (9) |

| FBLN7 | FBLN7, Fibulin-7, TM14 | Cell adhesion | Tfh cells | (12) |

| GF11 | GF11 | Regulation of transcription | Th1/B cells | (19) |

| GNLY | Granulysin, LAG2, NKG5 | Cellular defense response, defense response to bacterium fungus, killing of cells of other organism | Chemotaxis/Th1/cytotoxicity/activation | (9) |

| HLA-DRA | HLA-DRA | T cell costimulation, TCR signaling pathway, antigen processing and presentation of exogenous peptide or polysaccharide antigen via MHC class II, IFN-γ-mediated signaling pathway, immune response | Chemotaxis/Th1/cytotoxicity/activation | (9) |

| ICAM-3 | ICAM-3, CD50, ICAM-R | Cell adhesion, extracellular matrix organization, phagocytosis, regulation of immune response, stimulatory C-type lectin receptor signaling pathway | Chemotaxis/T cells | (5) |

| ICOS | ICOS, CD278 | T cell costimulation, T cell tolerance induction, immune response | Chemotaxis/Th1/cytotoxicity/activation, Tfh cells | (9, 12) |

| IFN-γ | IFN-γ | T cell receptor signaling pathway, Th1-related cytokine | Chemotaxis/Th1/cytotoxicity/activation | (9) |

| IGSF6 | IGSF6, DORA | Cell surface receptor signaling pathway, immune response | Th1/B cells | (19) |

| IL1R1 | IL1RA, IL1R, CD121A | Cell surface receptor signaling pathway, IL-1-mediated signaling pathway, regulation of inflammatory response, response to TGF-β | Th1/B cells | (19) |

| IL1R2 | IL1R2, CD121b, IL1RB | Inflammatory response, cytokine-mediated signaling pathway | Th1/B cells | (19) |

| IL-2 | IL-2, lymphokine, TCGF | MAPK cascade, T cell differentiation, adaptive immune response, extrinsic apoptosis signaling pathway in absence of ligand, NK cell activation, negative regulation of B-cell apoptotic process, positive regulation of B and activated T cell proliferation, positive regulation of Ig secretion, positive regulation of IFN-γ and IL-17 production, positive regulation of isotype switching to IgG, positive regulation of Treg differentiation, regulation of T cell homeostatic proliferation | Chemotaxis/Th1/cytotoxicity/activation | (9) |

| IL2RA | IL2RA, CD25, IL2R, p55 | Activation-induced cell death of T cells, positive regulation of activated T cell proliferation, positive regulation of T cell differentiation, inflammatory response, IL-2-mediated signaling pathway, regulation of T cell tolerance induction | Th1/B cells | (19) |

| IL-10 | IL-10, TGIF, GVHDS, CSIF | B-cell differentiation, inflammatory response, negative regulation of T- and B-cell proliferation, negative regulation of apoptotic process, negative regulation of cytokine activity, negative regulation of IFN-γ, IL-1, IL-12, IL-18, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF production, negative regulation of myeloid DC activation, positive regulation of JAK-STAT cascade, regulation of isotype switching, Th3/Tr1/regulatory immune responses | Chemotaxis/Th1/cytotoxicity/activation, Th1/B cells | (9, 19) |

| IL-12B | IL12B, CLMF, NKSF, IMD28, IMD29 | Positive regulation of Th1 and Th17 immune responses, Th differentiation, cellular response to IFN-γ, defense response to virus, positive regulation of NK and T cell activation, positive regulation of memory T cell differentiation, regulation of IL-10, IL-12, IL-17, TNF-α, and GM-CSF production, positive regulation of NK T cell activation and proliferation, positive regulation of T cell-mediated cytotoxicity, regulation of tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT1 | Chemotaxis/Th1/cytotoxicity/activation | (9) |

| IL-15 | IL-15 | NK T cell proliferation, extra-thymic T cell selection, inflammatory response, LN development, positive regulation of NK and T cell proliferation, positive regulation of IL-17 production, signal transduction, tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT5 | Chemotaxis/Th1/cytotoxicity/activation | (9) |

| IL-16 | IL-16, LCF, NIL16 | Immune response, induction of positive chemotaxis, regulation of transcription and DNA-templated | Chemotaxis/T cells | (5) |

| IL-18 | IL-18, IGIF, IL1γ, IL1F4 | MAPK cascade, Th1/Th2 immune response, GM-CSF biosynthetic process, inflammatory response, IFN-γ, IL-2, and IL-13 biosynthetic process, NK cell activation and proliferation, positive regulation of IL-17 and IFN-γ production, positive regulation of tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT3 | Chemotaxis/Th1/cytotoxicity/activation | (9) |

| IRF4 | IRF4, MUM1, LSIRF | T cell activation, Th17 cell lineage commitment, IFN-γ-mediated signaling pathway, positive regulation of IL-10, IL-13, IL-2, and IL-4 biosynthetic process, regulation of Th cell differentiation, Type-I IFN signaling pathway, positive regulation of transcription | Th1/B cells | (19) |

| ITGAL | ITGAL, CD11A, LFA-1 | Extracellular matrix organization, T cell activation via TCR contact with antigen bound to MHC molecule on APC, leukocyte migration, heterotypic cell–cell adhesion, immune response, integrin-mediated signaling pathway, inflammatory response, phagocytosis, regulation of immune response | Chemotaxis/T cells | (5) |

| ITGAD | ITGAD, ADB2, CD11D | Extracellular matrix organization, heterotypic cell–cell adhesion, immune response, integrin-mediated signaling pathway | Chemotaxis/T cells | (5) |

| ITGA4 | ITGA4, CD49D | B-cell differentiation, cell-matrix adhesion, diapedesis, extracellular matrix organization, heterotypic cell–cell adhesion, integrin-mediated signaling pathway, leukocyte migration tethering or rolling, regulation of immune response | Chemotaxis/T cells | (5) |

| LTA | LTA, Lymphotoxin α, TNFB, TNFSF1 | Positive regulation of apoptotic process, cell–cell signaling, positive regulation of humoral immune response mediated by circulating Ig, LN development, positive regulation of IFN-γ production, TNF-mediated signaling pathway | Chemotaxis/Th1/cytotoxicity/activation | (9) |

| MADCAM1 | MADCAM1 | Cell–matrix adhesion, extracellular matrix organization, heterotypic cell–cell adhesion, integrin-mediated signaling pathway, leukocyte tethering or rolling, receptor clustering, regulation of immune response, signal transduction | Chemotaxis/T cells | (5) |

| PDCD1 | PD-1 | T cell costimulation, humoral immune response, positive regulator of T cell apoptotic process | Tfh cells | (12) |

| PRF1 | Perforin, PFP, FLH2, PFN1 | Apoptotic process, cellular defense response, cytolysis, defense response to tumor cell, immunological synapse formation, transmembrane transport | Chemotaxis/Th1/cytotoxicity/activation | (9) |

| SDC1 | SDC, CD138, syndecan | Cell migration, inflammatory response, canonical Wnt signaling pathway | Th1/B cells | (19) |

| SGPP2 | SGPP2, Spp2, SPPase2 | Regulation of immune response, positive regulation of signal transduction, positive regulation of NK-mediated cytotoxicity | Tfh cells | (12) |

| SH2D1A | Signal transduction of T- and B-cell activation | Tfh cells | (12) | |

| STAT5A | STAT5A, MGF | JAK–STAT cascade, peptidyl-tyrosine phosphorylation, regulator of transcription | Th1/B cells | (19) |

| TBX21 | T-Bet, TBLYM | T cell differentiation, lymphocyte migration, positive regulation of transcription and DNA-templated, positive regulation of isotype switching to IgG | Chemotaxis/Th1/cytotoxicity/activation | (9) |

| TIGIT | TIGIT, VSTM3, VSIG9 | T cell co-inhibitory receptor, negative regulation of IL-12 production, positive regulation of IL-10 production | Tfh cells | (12) |

| TNF-α | TNF-α, DIF, TNFSF2 | I-kappaB kinase/NF-kappaB signaling, JNK cascade, MAPK cascade, activation of MAPK and MAPKKK activities, humoral immune response, inflammatory response, necroptotic signaling pathway, negative regulation of cytokine secretion, negative regulation of cytokine and chemokine production, negative regulation of transcription and DNA-templated, positive regulation of ERK1 and ERK2 cascade, positive regulation of I-kappaB kinase/NF-kappaB signaling, positive regulation of JUN and MAP kinase activity, positive regulation of apoptotic process, positive regulation of humoral response and Ig secretion | Chemotaxis/Th1/cytotoxicity/activation | (9) |

| TRAF6 | TRAF6, RNF85 | FcE receptor signaling pathway, JNK cascade, MyD88-dependent TLR signaling pathway, MyD88-independent TLR signaling pathway, TCR signaling pathway, Th1 immune response, activation of MAPK activity, Ag processing and presentation of exogenous peptide Ag, myeloid DC differentiation, positive regulation of T cell activation proliferation and cytokine production, positive regulation of IL-12 production, response to IL-1, TLR signaling pathway | Th1/B cells | (19) |

| VCAM-1 | VCAM-1, CD106 | B-cell differentiation, acute inflammatory response, cell–matrix adhesion, cellular response to TNF-α and VEGF, IFN-γ-mediated signaling pathway, leukocyte tethering or rolling, positive regulation of T cell proliferation, regulation of immune response, response to hypoxia | Chemotaxis/T cells | (5) |

Genes selectively overexpressed in tumors having high density of TLS in cancer patients.

In this mini review, we summarize the available data in the literature regarding the prognostic value of TLS in human cancers, and discuss how these structures are controlled and could be manipulated in order to increase anti-tumor immune responses.

TLS and Prognosis in Cancers

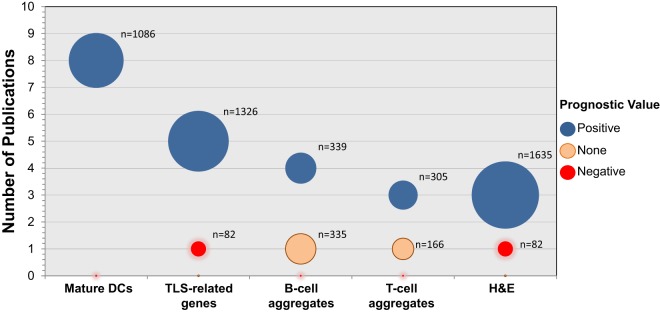

In recent years, numerous publications have assessed the prognosis associated with the presence of TLS in different types of tumors. Several strategies for their quantification have been used. Historically, the first method to measure the densities of TLS was the quantification of mature DCs (DC-Lamp+) within CD3+ T cell aggregates (1, 20). Although relatively challenging due to the relative low number of DC-Lamp+ DCs in some tumors (as compared to other immune populations), our group has described it as the most accurate marker for quantifying TLS (28, 29). Up-to-date, eight publications have found a positive association between increased densities of DC-Lamp+ DCs and prognosis, in several types of tumors, including NSCLC (1, 2, 9), melanoma (20), renal cell carcinoma [RCC (24)], breast (11), and colorectal cancer (15) (Table 1 and Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Prognostic value of TLS-associated biomarkers in primary and metastatic cancers. The number of publications studying the impact of mature DCs, TLS-related gene signatures, B-cell aggregates, T cell aggregates, or H&E with regard to prognosis in human cancers is represented (12 cancer types have been included). Blue, orange, and red circles represent an association with good, none, and poor prognosis, respectively. The diameter of the circles represents the total number of tumors (n) that have been analyzed on these studies.

The analysis of expression levels of TLS-related genes gives the possibility to rapidly assess the prognostic impact of these immune aggregates in large retrospective cohorts of tumors. So far, six studies have evaluated the prognostic impact of increased expression of TLS-related genes in cancer. Despite heterogeneity in the TLS-signatures, a significant correlation with good prognosis has been found in melanoma (21), colorectal (3, 18), and gastric (19) cancers (Table 1). Interestingly, TLS found in inflammatory zones from hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) correlate with increased risk for late recurrence and a trend toward decreased overall survival after HCC resection. This result could reflect an unexpected role for TLS, serving as niche for HCC progenitor cells via local production of Lymphotoxin (LT)-β (25, 30).

Another approach that has been used to estimate the densities of TLS in cancers is the quantification of B-cell aggregates by immunohistochemistry (IHC) (CD20+ B-cell aggregates or islets). The majority of publications measuring CD20+ aggregates (four out of five), accounting for more than 349 analyzed tumors, has determined that increased densities of this population correlate with good prognosis in several neoplasias, such as NSCLC (2), colorectal cancer liver metastasis (27), gastric (19), and oral (22) cancer (Table 1 and Figure 1). Most of the studies quantifying the CD3+ T cell aggregates and immune-cell aggregates (after hematoxylin counterstaining) have also found a positive impact on patient’s prognosis. However, high numbers of B cell or T cell aggregates were found to have no impact on prognosis in biliary tract cancer and in stage III colorectal cancer, respectively. Further studies are needed to investigate whether it reflects that cell aggregates counting is not an accurate method to quantify TLS, or a functional impairment of TLS in these two cancer types (Table 1 and Figure 1).

Overall, despite the heterogeneity of methods used for quantifying TLS, most of the studies have consistently found a correlation between high densities of TLS and prolonged patient’s survival in more than 10 different types of cancer (Table 1). Further efforts should be made to optimize TLS-quantifying methods. Indeed the use of multicolor IHC will facilitate their characterization, by allowing the simultaneous detection of all major cell types and providing an extensive analysis of their cellular complexity.

TLS Neogenesis

The cellular composition and spatial organization of TLS share many similarities with those of SLO. Indeed, an increasing number of studies performed in a large variety of inflammatory disorders, in mice and in humans, suggest that their formation and regulation involve the same set of chemokines than those acting in lymphoid organogenesis.

Positive Regulators

Lymphotoxin, CCL21, and CXCL13 were shown to play a major role during TLS neogenesis, and are related to TLS presence in human tumors (Table 2). In a mouse model of atherosclerosis, the activation of LTβR+ medial smooth muscle cells in the abdominal aorta by LT produced by CD11c+ CD68+ Ly6Clo monocytes leads to the expression of CCL19, CCL21, CXCL13, and CXCL16 chemokines, which in turn trigger the recruitment of lymphocytes to the adventitia and the development of TLS (31). The same observation was made by Thaunat et al. in a rat model of chronic allograft rejection, in which M1-macrophages behaved as LTi cells in diseased arteries by expressing high levels of LTα and TNF-α (32). In human NSCLC, a TLS-related gene signature was identified, including CCL19, CCL21, IL-16, and CXCL13 (5) (Table 2). Interestingly, Matsuda et al. recently suggested in a mouse intrapulmonary tracheal transplant model that lymphoid neogenesis was dependent on spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk)-signaling. Decreased expression of CXCL12, CXCL13, and VEGF-α, lower B-cell recruitment into allograft, and smaller lymphoid aggregate area were observed in Syk-deficient recipient mice as compared to controls (33).

The generation of HEVs is also a critical step in TLS neogenesis. HEV endothelial cells express LTβR, and the continuous engagement of LTβR on HEVs by LT+ CD11c+ DCs is critical for the induction and maintenance of the mature HEV phenotype required for the extravasation of blood lymphocyte into LNs (34–37). In addition, CD11c+ DCs can be sources of proangiogenic factors, such as VEGF, favoring the development of HEVs, and ultimately lymphocyte entry into LN (38–41). Consistently, LTβ expression correlates with that of HEV-associated chemokines in human breast cancer, and DC-Lamp+ DC density correlates with HEV density, lymphocyte infiltration, and favorable clinical outcome (11). Other cell types were shown to favor the development of HEV. For instance, ectopic expression of CCL21 in the thyroid gives rise first to the recruitment of CD3+ CD4+ T cells followed by DC, and this DC-T cross-talk is required for the local development of both TLS and mature HEV (42). Tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells and NK cells were also shown to drive the de novo development of PNAd+ TNFRI+ CCL21+ HEV-like blood vessels through the production of LT and IFN-γ (43).

Th17 cells share many developmental and effector markers with LTi cells, including the nuclear hormone receptor retinoic acid-related orphan receptor γt (RORγt), which promotes not only the production of IL-17 and IL-22 by Th17 cells, LTi cells, and other RORγt+ innate lymphoid cells (ILCs), but also cell membrane expression of LT [reviewed in Ref. (44)]. In mice lungs, the formation of TLS [called here induced-bronchus-associated lymphoid tissues (i-BALT)] following LPS sensitization was dependent of IL-17 production by T cells, including Th17 and γδ T cells (45). This observation was also observed in a mouse experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) model of multiple sclerosis (46). Similarly, IL-17α-deficient mice exposed to cigarette smoke displayed decreased number of ectopic lymphoid follicles and decreased expression of CXCL12 as compared to wild-type mice in a model of chronic obstructive lung disease (47). It has also been suggested that Th17 cells, and IL-17 and IL-21 secretion by these cells can promote TLS neogenesis within human renal grafts, and are associated with the presence of active GC B cells and fast chronic rejection (48).

Other inflammatory cytokines also seem to promote TLS neogenesis. In rheumatoid arthritis (RA), high protein levels of IL-23 and IL-17F were detected in the synovial fluid of patients displaying ectopic lymphoid follicles, and a positive correlation was observed between CD21L mRNA (as a TLS marker) and IL-23 but also IL-17F, IL-21, and IL-22 mRNAs (49). IL-22 was also proposed to favor TLS induction (50). In a mouse model of virus-induced autoantibody formation in the salivary glands, it was shown that the ligation of IL-22R expressed by epithelial cells and fibroblasts leads to CXCL12 and CXCL13 production, allowing B-cell recruitment and TLS organization. In that case, IL-22 was mainly produced by γδ T cells and to a lesser extent by ILCs and NK cells during the early phase post-infection, and then by αβ T cells later after infection.

Negative Regulators

On the opposite, IL-27, a cytokine known to inhibit effector Th17 responses was recently suggested to negatively regulate the development of ectopic lymphoid-like structures in the synovial tissues of RA patients. While patients having a high density of TLS displayed high synovial levels of IL-17 and IL-21, high levels of IL-27 were observed in patients devoid of any TLS, and IL-27 expression was inversely correlated with CD3+ and CD20+ infiltrates and with synovitis. This observation was confirmed in a mouse model of RA (51).

Among the immune cells infiltrating tumors are regulatory T cells (Tregs), which have been considered in many reports as a marker of poor prognosis in cancer (52, 53). Tregs have been reported to negatively interfere with BALT development. Indeed in CCR7-deficient mice, BALTs developed spontaneously in the absence of infection, an event that is directly reverted by the adoptive transfer of wild-type Tregs but not CCR7−/− Tregs (54). In human breast cancer, Tregs were detected in lymphoid aggregates surrounding tumor nests, and their presence was linked with the poor clinical outcome of patients (55). In mice bearing breast tumors, Treg depletion led to an increased density of HEV within the tumor, facilitated T cell recruitment from the blood, and ultimately induced tumor destruction (56). This observation is in accordance with a human study showing that HEVhigh breast tumors correlated with a high LT-β expression, a high density of tumor-infiltrating mature DC, and a decreased FoxP3+/CD3+ T cell ratio (11).

More recently, a new mechanism involving regulation of TLS formation by Tregs was found, by dampening neutrophilic inflammation (57). The presence of neutrophils seemed to be critical for the neogenesis and the humoral immune function of i-BALT by enhancing B-cell activation and survival, Ig class switching to IgA as well as plasma cell survival (57).

Regulatory T cells have been shown to dampen the effector T cell response promoted within tumor-associated TLS. Treg depletion causes immune-mediated tumor destruction associated with an increased expression of co-stimulatory ligands by DCs and proliferation of T cells in a murine model of lung adenocarcinoma (58). Further studies should be carried out to analyze the prognostic importance of Tregs and their immunosuppressive potential in cancer patients according to their localization.

Altogether, TLS neogenesis and lymphoid organogenesis share many common mechanisms. On the one hand, the production of inflammatory cytokines (LT, IL-17, IL-22, and IL-23) and lymphoid chemokines (CCL21, CXCL12, and CXCL13), HEV development as well as the activation of DCs, B, and effector cells seem to be crucial events leading to TLS neogenesis under inflammatory conditions, such as cancers. On the other hand, the presence of Tregs appears to negatively impact TLS formation and TLS-associated T cell responses.

Manipulation of TLS for a Therapeutic Intervention in Cancer

A series of studies suggest that TLS are sites for generation and maintenance of adaptive anti-tumor responses (10). Therefore, TLS induction could be used as a therapeutic intervention for a better tumor control and prolonged survival of cancer patients. Since LN and TLS share many similarities in terms of cellular composition and organization, deciphering the mechanisms of lymphoid organogenesis enables to first highlight some putative key molecules that can support TLS neogenesis.

Targeting Molecules Involved in Lymphoid Organogenesis

The key cross-talk between LTi cells and lymphoid tissue organizer cells (LTo cells that are cells of mesenchymal origin) occurring during LN development involves several molecules along with RANK and its ligand, which lead to LTβR signaling (59). Therefore, targeting RANK/LT pathway may modulate TLS development through the activation of LTo cells. Currently, antagonists of LTα (Pateclizumab NCT01225393), LTβR (Baminercept, NCT01552681) and RANK signaling (NCT01973569) are under investigation in several inflammatory situations. A special attention should be made in cancer setting where these antagonists might block TLS formation and, hence, reduce survival. The use of agonists might rather present a benefit to cancer patients but no drugs have been developed so far.

Activation of LTβR signaling pathway in LTo cells induces VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 upregulation, and ultimately leukocyte infiltration (60). Because both molecules are known to be induced by inflammation, an ICAM-1 antagonist called Alicaforsen has been tested in autoimmune diseases (NCT00048113, NCT00063830). We can speculate that the development of VCAM-1/ICAM-1 agonists would promote LTi-like cells-LTo clusterings and improve the leukocyte recruitment in order to generate cancer-associated TLS.

IL-7 receptor (CD127) signaling has been reported as a key pathway for TLS neogenesis (61). IL-7 is not only crucial for the survival and proliferation of LTi cells but also for GC formation and Tfh differentiation (62). To date, only one pharmacologic agent (IL-7R) is under investigation in NOD mice to deplete autoreactive T cells and to regulate pro-inflammatory mediators (63).

Altogether, as a counterpart of autoimmune diseases, development of agonist molecules targeting lymphoid organogenesis might be a promising strategy for the initiation and the maintenance of TLS in cancers.

Modulation of Chemokine and Cytokine Networks

Lymphoid chemokines represent a good therapeutic target for the modulation of TLS (Table 2). The CCL19–CCL21/CCR7 and CXCL13/CXCR5 couples are induced after LT-βR signaling during lymphoid genesis (60). They are overexpressed in TLS of melanoma (21), colorectal (3), and lung (5) cancer patients. Using lymphoid chemokines or their agonists could be a promising strategy to induce TLS neogenesis in cancers. For example, CCL21 has been shown to attract circulating naïve T cells and DCs in tumors, and contribute to the control of tumor growth (64–66). A Phase I clinical trial is currently under investigation in NSCLC patients receiving intra-tumoral injections of CCL21-transduced autologous DCs (NCT00601094, NCT01574222). It is tempting to speculate that this vaccine therapy would boost TLS formation in tumors associated with an influx of lymphocytes, an effective anti-tumor immune response, and a reduction of tumor burden.

IL-21, which is mainly secreted by Th17 cells and neutrophils, represents also an interesting molecular target. First, this cytokine has been shown to promote TLS neogenesis in lungs after acute LPS exposure and IL-21−/− mice exhibit fewer TLS in allografts than the control group (57). Second, IL-21 can enhance B and plasma cell survival as well as B-cell-dependent immunity, and induce conventional T cells to become refractory to Treg immunosuppression (48, 57, 67). Even if IL-21 can block IL-2 production with deleterious consequences in terms of Treg differentiation, IL-21 can substitute for IL-2 as a T cell growth factor (68). Recombinant IL-21 is currently tested in many clinical trials, alone or in combination with chemotherapy, therapeutic antibodies or tyrosine kinase inhibitors (e.g., NCT00617253, NCT00389285, NCT00095108, NCT01629758, NCT00336986, and NCT01489059). Altogether, it is likely that IL-21 could promote a robust anti-tumor immunity in a TLS-dependent manner.

Conclusion and Perspectives

By facilitating the direct entry of CCR7+ naïve T cells and CXCR5+ B cells into tumors through HEVs, TLS allow T cells to differentiate into effector cells upon contact with mature DCs and B cells to form GC, protected from the immunosuppressive milieu of the tumor microenvironment. Therefore, TLS represent sites for the induction and maintenance of the local and systemic anti-tumor responses, which confer long-term protection against metastasis and, hence, correlate with good prognosis for the patients. Indeed, therapies aiming to increase TLS formation may allow generating anti-tumor responses directly in situ and would be beneficial in patients with high mutational load. TLS may also constitute biomarkers of anti-tumor response in patients undergoing immunotherapies. Thus, TLS induction was observed in cervical cancer patients vaccinated with HPV DNA (69) or with G-VAX (70), and one may speculate that TLS signature could be used to evidence response to therapies that unlock the adaptive immune responses.

Author Contributions

ML, NG, HK, CG, and CSF wrote and revised the paper. WF and MCDN revised the paper.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank all members of the Laboratory “Cancer, Immune control and Escape,” pathologists and clinicians who have participated in these studies, for their help and valuable discussions, as well as cancer patients.

Funding

This work was supported by Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (INSERM), University Paris Descartes, University Pierre et Marie Curie, the Institut National du Cancer (2009-1-PLBIO07-INSERM6-, 2010-1-PLBIO03-INSERM 6-1, 2011-1-PLBIO-06-INSERM 6-1, PLBIO09-088-IDF-KROEMER), CARPEM (CAncer Research for PErsonalized Medicine), the Labex Immuno-Oncology (LAXE62_9UMS872 FRIDMAN), foundation ARC pour la recherche sur le cancer (SL220110603483), Ligue Nationale contre le Cancer (GB/MA/CD/EP-12003), and MedImmune (Gaithersburg, USA, n°11796A10). HK was supported by a grant from La Ligue contre le Cancer.

References

- 1.Dieu-Nosjean MC, Antoine M, Danel C, Heudes D, Wislez M, Poulot V, et al. Long-term survival for patients with non-small-cell lung cancer with intratumoral lymphoid structures. J Clin Oncol (2008) 26(27):4410–7. 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.0284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Germain C, Gnjatic S, Tamzalit F, Knockaert S, Remark R, Goc J, et al. Presence of B cells in tertiary lymphoid structures is associated with a protective immunity in patients with lung cancer. Am J Respir Crit Care Med (2014) 189(7):832–44. 10.1164/rccm.201309-1611OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coppola D, Nebozhyn M, Khalil F, Dai H, Yeatman T, Loboda A, et al. Unique ectopic lymph node-like structures present in human primary colorectal carcinoma are identified by immune gene array profiling. Am J Pathol (2011) 179(1):37–45. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.03.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cipponi A, Mercier M, Seremet T, Baurain JF, Théate I, van den Oord J, et al. Neogenesis of lymphoid structures and antibody responses occur in human melanoma metastases. Cancer Res (2012) 72(16):3997–4007. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Chaisemartin L, Goc J, Damotte D, Validire P, Magdeleinat P, Alifano M, et al. Characterization of chemokines and adhesion molecules associated with T cell presence in tertiary lymphoid structures in human lung cancer. Cancer Res (2011) 71(20):6391–9. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martinet L, Garrido I, Girard JP. Tumor high endothelial venules (HEVs) predict lymphocyte infiltration and favorable prognosis in breast cancer. Oncoimmunology (2012) 1(5):789–90. 10.4161/onci.19787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martinet L, Le Guellec S, Filleron T, Lamant L, Meyer N, Rochaix P, et al. High endothelial venules (HEVs) in human melanoma lesions: major gateways for tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. Oncoimmunology (2012) 1(6):829–39. 10.4161/onci.20492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martinet L, Garrido I, Filleron T, Le Guellec S, Bellard E, Fournie JJ, et al. Human solid tumors contain high endothelial venules: association with T- and B-lymphocyte infiltration and favorable prognosis in breast cancer. Cancer Res (2011) 71(17):5678–87. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goc J, Germain C, Vo-Bourgais TK, Lupo A, Klein C, Knockaert S, et al. Dendritic cells in tumor-associated tertiary lymphoid structures signal a Th1 cytotoxic immune contexture and license the positive prognostic value of infiltrating CD8 + T cells. Cancer Res (2014) 74(3):705–15. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hosmalin A, Sautès-Fridman C, Fougereau M, Yssel H, Fischer A. 50(th) Anniversary of the French Society for Immunology (SFI). Eur J Immunol (2016) 46(7):1545–7. 10.1002/eji.20167007327401870 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martinet L, Filleron T, Le Guellec S, Rochaix P, Garrido I, Girard JP. High endothelial venule blood vessels for tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes are associated with lymphotoxin β-producing dendritic cells in human breast cancer. J Immunol (2013) 191(4):2001–8. 10.4049/jimmunol.1300872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gu-Trantien C, Loi S, Garaud S, Equeter C, Libin M, de Wind A, et al. CD4+ follicular helper T cell infiltration predicts breast cancer survival. J Clin Invest (2013) 123(7):2873–92. 10.1172/JCI67428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee HJ, Park IA, Song IH, Shin SJ, Kim JY, Yu JH, et al. Tertiary lymphoid structures: prognostic significance and relationship with tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes in triple-negative breast cancer. J Clin Pathol (2016) 69(5):422–30. 10.1136/jclinpath-2015-203089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Väyrynen JP, Sajanti SA, Klintrup K, Mäkelä J, Herzig KH, Karttunen TJ, et al. Characteristics and significance of colorectal cancer associated lymphoid reaction. Int J Cancer (2014) 134(9):2126–35. 10.1002/ijc.28533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Remark R, Alifano M, Cremer I, Lupo A, Dieu-Nosjean MC, Riquet M, et al. Characteristics and clinical impacts of the immune environments in colorectal and renal cell carcinoma lung metastases: influence of tumor origin. Clin Cancer Res (2013) 19(15):4079–91. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McMullen TPW, Lai R, Dabbagh L, Wallace TM, de Gara CJ. Survival in rectal cancer is predicted by T cell infiltration of tumour-associated lymphoid nodules. Clin Exp Immunol (2010) 161(1):81–8. 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04147.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Di Caro G, Bergomas F, Grizzi F, Doni A, Bianchi P, Malesci A, et al. Occurrence of tertiary lymphoid tissue is associated with T-cell infiltration and predicts better prognosis in early-stage colorectal cancers. Clin Cancer Res (2014) 20(8):2147–58. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bindea G, Mlecnik B, Tosolini M, Kirilovsky A, Waldner M, Obenauf AC, et al. Spatiotemporal dynamics of intratumoral immune cells reveal the immune landscape in human cancer. Immunity (2013) 39(4):782–95. 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hennequin A, Derangère V, Boidot R, Apetoh L, Vincent J, Orry D, et al. Tumor infiltration by Tbet + effector T cells and CD20 + B cells is associated with survival in gastric cancer patients. Oncoimmunology (2016) 5(2):e1054598. 10.1080/2162402X.2015.1054598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ladányi A, Kiss J, Somlai B, Gilde K, Fejos Z, Mohos A, et al. Density of DC-LAMP(+) mature dendritic cells in combination with activated T lymphocytes infiltrating primary cutaneous melanoma is a strong independent prognostic factor. Cancer Immunol Immunother (2007) 56(9):1459–69. 10.1007/s00262-007-0286-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Messina JL, Fenstermacher DA, Eschrich S, Qu X, Berglund AE, Lloyd MC, et al. 12-chemokine gene signature identifies lymph node-like structures in melanoma: potential for patient selection for immunotherapy? Sci Rep (2012) 2:765. 10.1038/srep00765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wirsing AM, Rikardsen OG, Steigen SE, Uhlin-Hansen L, Hadler-Olsen E. Characterisation and prognostic value of tertiary lymphoid structures in oral squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Clin Pathol (2014) 14:38. 10.1186/1472-6890-14-38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hiraoka N, Ino Y, Yamazaki-Itoh R, Kanai Y, Kosuge T, Shimada K. Intratumoral tertiary lymphoid organ is a favourable prognosticator in patients with pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer (2015) 112(11):1782–90. 10.1038/bjc.2015.145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Giraldo NA, Becht E, Pagès F, Skliris G, Verkarre V, Vano Y, et al. Orchestration and prognostic significance of immune checkpoints in the microenvironment of primary and metastatic renal cell cancer. Clin Cancer Res (2015) 21(13):3031–40. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Finkin S, Yuan D, Stein I, Taniguchi K, Weber A, Unger K, et al. Ectopic lymphoid structures function as microniches for tumor progenitor cells in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Immunol (2015) 16(12):1235–44. 10.1038/ni.3290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goeppert B, Frauenschuh L, Zucknick M, Stenzinger A, Andrulis M, Klauschen F, et al. Prognostic impact of tumour-infiltrating immune cells on biliary tract cancer. Br J Cancer (2013) 109(10):2665–74. 10.1038/bjc.2013.610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meshcheryakova A, Tamandl D, Bajna E, Stift J, Mittlboeck M, Svoboda M, et al. B cells and ectopic follicular structures: novel players in anti-tumor programming with prognostic power for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. PLoS One (2014) 9(6):e99008. 10.1371/journal.pone.0099008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dieu-Nosjean MC, Giraldo NA, Kaplon H, Germain C, Fridman WH, Sautès-Fridman C. Tertiary lymphoid structures, drivers of the anti-tumor responses in human cancers. Immunol Rev (2016) 271(1):260–75. 10.1111/imr.12405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dieu-Nosjean MC, Goc J, Giraldo NA, Sautès-Fridman C, Fridman WH. Tertiary lymphoid structures in cancer and beyond. Trends Immunol (2014) 35(11):571–80. 10.1016/j.it.2014.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sautès-Fridman C, Fridman WH. TLS in tumors: what lies within. Trends Immunol (2016) 37(1):1–2. 10.1016/j.it.2015.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gräbner R, Lötzer K, Döpping S, Hildner M, Radke D, Beer M, et al. Lymphotoxin beta receptor signaling promotes tertiary lymphoid organogenesis in the aorta adventitia of aged ApoE-/- Mice. J Exp Med (2009) 206(1):233–48. 10.1084/jem.20080752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thaunat O, Field AC, Dai J, Louedec L, Patey N, Bloch MF, et al. Lymphoid neogenesis in chronic rejection: evidence for a local humoral alloimmune response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2005) 102(41):14723–8. 10.1073/pnas.0507223102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matsuda Y, Wang X, Oishi H, Guan Z, Saito M, Liu M, et al. Spleen tyrosine kinase modulates fibrous airway obliteration and associated lymphoid neogenesis after transplantation. Am J Transplant (2016) 16(1):342–52. 10.1111/ajt.13442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Browning JL, Allaire N, Ngam-Ek A, Notidis E, Hunt J, Perrin S, et al. Lymphotoxin-beta receptor signaling is required for the homeostatic control of HEV differentiation and function. Immunity (2005) 23(5):539–50. 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liao S, Ruddle NH. Synchrony of high endothelial venules and lymphatic vessels revealed by immunization. J Immunol (2006) 177(5):3369–79. 10.4049/jimmunol.177.5.3369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kumar V, Scandella E, Danuser R, Onder L, Nitschké M, Fukui Y, et al. Global lymphoid tissue remodeling during a viral infection is orchestrated by a B cell-lymphotoxin-dependent pathway. Blood (2010) 115(23):4725–33. 10.1182/blood-2009-10-250118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moussion C, Girard JP. Dendritic cells control lymphocyte entry to lymph nodes through high endothelial venules. Nature (2011) 479(7374):542–6. 10.1038/nature10540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wendland M, Willenzon S, Kocks J, Davalos-Misslitz AC, Hammerschmidt SI, Schumann K, et al. Lymph node T cell homeostasis relies on steady state homing of dendritic cells. Immunity (2011) 35(6):945–57. 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sozzani S, Rusnati M, Riboldi E, Mitola S, Presta M. Dendritic cell-endothelial cell cross-talk in angiogenesis. Trends Immunol (2007) 28(9):385–92. 10.1016/j.it.2007.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Webster B, Ekland EH, Agle LM, Chyou S, Ruggieri R, Lu TT. Regulation of lymph node vascular growth by dendritic cells. J Exp Med (2006) 203(8):1903–13. 10.1084/jem.20052272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Benahmed F, Chyou S, Dasoveanu D, Chen J, Kumar V, Iwakura Y, et al. Multiple CD11c + cells collaboratively express IL-1β to modulate stromal vascular endothelial growth factor and lymph node vascular-stromal growth. J Immunol (2014) 192(9):4153–63. 10.4049/jimmunol.1301765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marinkovic T, Garin A, Yokota Y, Fu YX, Ruddle NH, Furtado GC, et al. Interaction of mature CD3 + CD4 + T cells with dendritic cells triggers the development of tertiary lymphoid structures in the thyroid. J Clin Invest (2006) 116(10):2622–32. 10.1172/JCI28993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peske JD, Thompson ED, Gemta L, Baylis RA, Fu YX, Engelhard VH. Effector lymphocyte-induced lymph node-like vasculature enables naive T-cell entry into tumours and enhanced anti-tumour immunity. Nat Commun (2015) 6:7114. 10.1038/ncomms8114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grogan JL, Ouyang W. A role for Th17 cells in the regulation of tertiary lymphoid follicles. Eur J Immunol (2012) 42(9):2255–62. 10.1002/eji.201242656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rangel-Moreno J, Carragher DM, de la Luz Garcia-Hernandez M, Hwang JY, Kusser K, Hartson L, et al. The development of inducible bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue depends on IL-17. Nat Immunol (2011) 12(7):639–46. 10.1038/ni.2053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Peters A, Pitcher LA, Sullivan JM, Mitsdoerffer M, Acton SE, Franz B, et al. Th17 cells induce ectopic lymphoid follicles in central nervous system tissue inflammation. Immunity (2011) 35(6):986–96. 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.10.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roos AB, Sandén C, Mori M, Bjermer L, Stampfli MR, Erjefält JS. IL-17A is elevated in end-stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and contributes to cigarette smoke-induced lymphoid neogenesis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med (2015) 191(11):1232–41. 10.1164/rccm.201410-1861OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Deteix C, Attuil-Audenis V, Duthey A, Patey N, McGregor B, Dubois V, et al. Intragraft Th17 infiltrate promotes lymphoid neogenesis and hastens clinical chronic rejection. J Immunol (2010) 184(9):5344–51. 10.4049/jimmunol.0902999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cañete JD, Celis R, Yeremenko N, Sanmartí R, van Duivenvoorde L, Ramírez J, et al. Ectopic lymphoid neogenesis is strongly associated with activation of the IL-23 pathway in rheumatoid synovitis. Arthritis Res Ther (2015) 17:173. 10.1186/s13075-015-0688-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barone F, Nayar S, Campos J, Cloake T, Withers DR, Toellner KM, et al. IL-22 regulates lymphoid chemokine production and assembly of tertiary lymphoid organs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2015) 112(35):11024–9. 10.1073/pnas.1503315112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jones GW, Bombardieri M, Greenhill CJ, McLeod L, Nerviani A, Rocher-Ros V, et al. Interleukin-27 inhibits ectopic lymphoid-like structure development in early inflammatory arthritis. J Exp Med (2015) 212(11):1793–802. 10.1084/jem.20132307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fridman WH, Pagès F, Sautès-Fridman C, Galon J. The immune contexture in human tumours: impact on clinical outcome. Nat Rev Cancer (2012) 12(4):298–306. 10.1038/nrc3245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Becht E, Giraldo NA, Germain C, de Reyniès A, Laurent-Puig P, Zucman-Rossi J, et al. Immune contexture, immunoscore, and malignant cell molecular subgroups for prognostic and theranostic classifications of cancers. Adv Immunol (2016) 130:95–190. 10.1016/bs.ai.2015.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kocks JR, Davalos-Misslitz AC, Hintzen G, Ohl L, Förster R. Regulatory T cells interfere with the development of bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue. J Exp Med (2007) 204(4):723–34. 10.1084/jem.20061424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gobert M, Treilleux I, Bendriss-Vermare N, Bachelot T, Goddard-Leon S, Arfi V, et al. Regulatory T cells recruited through CCL22/CCR4 are selectively activated in lymphoid infiltrates surrounding primary breast tumors and lead to an adverse clinical outcome. Cancer Res (2009) 69(5):2000–9. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hindley JP, Jones E, Smart K, Bridgeman H, Lauder SN, Ondondo B, et al. T-cell trafficking facilitated by high endothelial venules is required for tumor control after regulatory T-cell depletion. Cancer Res (2012) 72(21):5473–82. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Foo SY, Zhang V, Lalwani A, Lynch JP, Zhuang A, Lam CE, et al. Regulatory T cells prevent inducible BALT formation by dampening neutrophilic inflammation. J Immunol (2015) 194(9):4567–76. 10.4049/jimmunol.1400909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Joshi NS, Akama-Garren EH, Lu Y, Lee DY, Chang GP, Li A, et al. Regulatory T cells in tumor-associated tertiary lymphoid structures suppress anti-tumor T cell responses. Immunity (2015) 43(3):579–90. 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mebius, Reina E. Organogenesis of lymphoid tissues. Nat Rev Immunol (2003) 3(4):292–303. 10.1038/nri1054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dejardin E, Droin NM, Delhase M, Haas E, Cao Y, Makris C, et al. The lymphotoxin-beta receptor induces different patterns of gene expression via two NF-kappaB pathways. Immunity (2002) 17(4):525–35. 10.1016/S1074-7613(02)00423-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Meier D, Bornmann C, Chappaz S, Schmutz S, Otten LA, Ceredig R, et al. Ectopic lymphoid-organ development occurs through interleukin 7-mediated enhanced survival of lymphoid-tissue-inducer cells. Immunity (2007) 26(5):643–54. 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Seo YB, Im SJ, Namkoong H, Kim SW, Choi YW, Kang MC, et al. Crucial roles of interleukin-7 in the development of T follicular helper cells and in the induction of humoral immunity. J Virol (2014) 88(16):8998–9009. 10.1128/JVI.00534-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lee LF, Logronio K, Tu GH, Zhai W, Ni I, Mei L, et al. Anti-IL-7 Receptor-α reverses established type 1 diabetes in non-obese diabetic mice by modulating effector T-cell function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2012) 109(31):12674–9. 10.1073/pnas.1203795109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vicari AP, Ait-Yahia S, Chemin K, Mueller A, Zlotnik A, Caux C. Antitumor effects of the mouse chemokine 6Ckine/SLC through angiostatic and immunological mechanisms. J Immunol (2000) 165(4):1992–2000. 10.4049/jimmunol.165.4.1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nomura T, Hasegawa H, Kohno M, Sasaki M, Fujita S. Enhancement of anti-tumor immunity by tumor cells transfected with the secondary lymphoid tissue chemokine EBI-1-ligand chemokine and stromal cell-derived factor-1alpha chemokine genes. Int J Cancer (2001) 91(5):597–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yang SC, Batra RK, Hillinger S, Reckamp KL, Strieter RM, Dubinett SM, et al. Intrapulmonary administration of CCL21 gene-modified dendritic cells reduces tumor burden in spontaneous murine bronchoalveolar cell carcinoma. Cancer Res (2006) 66(6):3205–13. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kuchen S, Robbins R, Sims GP, Sheng C, Phillips TM, Lipsky PE, et al. Essential role of IL-21 in B cell activation, expansion, and plasma cell generation during CD4 + T cell-B cell collaboration. J Immunol (2007) 179(9):5886–96. 10.4049/jimmunol.179.9.5886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Attridge K, Wang CJ, Wardzinski L, Kenefeck R, Chamberlain JL, Manzotti C, et al. IL-21 inhibits T cell IL-2 production and impairs treg homeostasis. Blood (2012) 119(20):4656–64. 10.1182/blood-2011-10-388546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Maldonado L, Teague JE, Morrow MP, Jotova I, Wu TC, Wang C, et al. Intramuscular therapeutic vaccination targeting HPV16 induces T cell responses that localize in mucosal lesions. Sci Transl Med (2014) 6(221):221ra13. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lutz ER, Wu AA, Bigelow E, Sharma R, Mo G, Soares K, et al. Immunotherapy converts non-immunogenic pancreatic tumors into immunogenic foci of immune regulation. Cancer Immunol Res (2014) 2(7):616–31. 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]