Abstract

Sexual minorities and racial minorities experience greater negative impact following sexual assault. We examined recovery from sexual assault among women who identified as heterosexual and bisexual across racial groups. A community sample of women (N = 905) completed three yearly surveys about sexual victimization, recovery outcomes, race group, and sexual minority status. Bisexual women and Black women reported greater recovery problems. However, Black women improved more quickly on depression symptoms than non-Black women. Finally, repeated adult victimization uniquely undermined survivors’ recovery, even when controlling for child sexual abuse. Sexual minority and race status variables and their intersections with revictimization play roles in recovery and should be considered in treatment protocols for sexual assault survivors.

Keywords: Sexual assault, revictimization, sexual minorities, racial minorities, psychological outcomes

Sexual assault is a common, yet underrecognized form of family violence, with approximately one-fourth of women experiencing lifetime attempted or completed rape (Kilpatrick, Resnick, Ruggiero, Conoscenti, & McCauley, 2007). Such high prevalence of sexual victimization is cause for concern, as both childhood and adulthood victimization is connected to harmful effects on women’s mental health (see Campbell, Dworkin, & Cabral, 2009 for a review). Even though a history of trauma is connected with negative psychosocial adjustment for women in general, certain subgroups have more serious effects of these types of experiences. In this study, we investigate the psychological adjustment of sexual assault survivors and how that is impacted by survivors’ sexual and racial minority status as well as trauma history.

Sexual Assault Victimization and Recovery of Sexual Minorities

Sexual violence victimization and recovery of non-heterosexuals remains understudied (Balsam, Beauchaine & Rothblum, 2005). This is particularly problematic as lesbian and bisexual women are at greater risk for sexual victimization than heterosexuals (Drabble, Trocki, Hughes, Korcha & Lown, 2013; Rothman, Exner & Baughman, 2011; Walters, Chen & Breiding, 2013). In fact, sexual orientation predicts increased risk of victimization even when other known risk factors are statistically controlled (e.g., gender, age, education; Balsam et al., 2005). The risk of sexual violence is elevated for sexual minorities both in childhood and adulthood (Friedman et al., 2011; Hughes, McCabe, Wilsnack, West, & Boyd, 2010; Morris & Balsam, 2003; Roberts, Austin, Corliss, Vandermorris, & Koenen, 2010; Rothman et al., 2011). A recent study of lesbian and bisexual women has even identified sexual minority status as a risk factor for trauma (Balsam et al., 2015). Risk of sexual victimization may therefore be higher among sexual minorities.

Although research has not precisely identified why sexual minorities experience greater sexual victimization, we present two possibilities. First, sexual minorities may experience homophobic harassment because of their sexual orientation. For example, in 2011, sexual violence accounted for 3% of the 3,162 reported hate crimes against Lesbian/Gay/Bisexual/Transgender/Questioning/HIV-affected (LGBTQH) people, with sexual harassment accounting for another 3% (National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs, 2011). Second, sexual minority stress can help explain why this group is at higher risk of victimization. Non-heterosexuals may experience discrimination and systematic oppression from living in a homophobic society (DiPlacido, 1998). Sexual minority stress may lead to increased psychological distress and increased risk behaviors that make this population vulnerable to sexual victimization. Not only does this chronic stress put sexual minorities at increased risk for sexual assault, but it can also make recovery from sexual assault more difficult (Balsam et al., 2005). This effect may be even more pronounced among bisexual survivors, who may experience sexual minority stress as well as marginalization from the gay community. Research on recovery supports this idea, with bisexual survivors reporting greater PTSD symptoms (Long et al., 2007; Sigurvinsdottir & Ullman, 2015) and problem drinking (Sigurvinsdottir & Ullman, 2015) than both lesbian and heterosexual survivors. Because of all these factors, sexual minorities are likely to have different needs than heterosexual survivors.

Risk of Sexual Assault for Different Race Groups

The survivor’s race can also be a risk factor for sexual assault (see Abbey, Jacques-Tiaura, & Parkhill [2010] for a review). For example, child sexual abuse (CSA) victimization prevalence is high among Black women, with estimates ranging from 34% to 65% in community samples (adults reporting on their own victimization as children) (Amodeo, Griffin, Fassler, Clay & Ellis, 2006; Bryant-Davis, Ullman, Tsong, Tillman & Smith, 2010). Black women are also at risk for adult sexual assault (rape lifetime estimates of 19–22% in population samples of Black women; Black et al., 2011; Tjaden & Thoennes, 2006). When sexual coercion is included, that number increases to 41% according to data from the recent National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NIPSVS; Black et al., 2011). In general, representative sample studies have shown similar rates of sexual victimization for Black and White women. For example, Wyatt (1992) found similar rates of sexual assault in White and African-American representatively sampled women in Los Angeles. Conversely, some nonrepresentative study samples have shown higher rates in Black women (see Abbey et al., 2010 for a review). This may be due to income disparities, as lower income Black women face much higher rates of sexual assault. For example, Temple, Weston, Rodriguez, and Marshall (2007) found that 67% of poor Black women experienced sexual assault. In addition, Black women may also be more likely to experience sexual assault in intimate partner relationships, which may be a more hidden, yet more prevalent, form of sexual assault (West, 2013).

Subgroups of Black women are at even greater risk for sexual violence, particularly women who are low-income, living with HIV, sexual minorities, and incarcerated Black women. For example, Black bisexual college women reported higher rates of sexual assault (13.2%) than Black heterosexual women (9.5%; Krebs, Lindquist & Barrick, 2011). Furthermore, people of color in the Lesbian/Gay/Bisexual community are more likely than Whites to have been victimized (Arreola, Neilands, Pollack, Paul, & Catania, 2005; Balsam, Lehavot, Beadnell, & Circo, 2015; Dunbar, 2006; Meyer, 2010; Morris & Balsam, 2003). In fact, violence based on race, social class, and sexual orientation has been described as a ‘web of trauma’ (West, 2002). These studies suggest that certain racial and sexual minorities may have different experiences with sexual victimization.

Psychological Recovery from Sexual Victimization of Sexual and Racial Minority Survivors

Sexual assault survivors may experience problems following their victimization, such as alcohol or drug use, PTSD symptoms, and depression (Campbell et al., 2009). This negative impact is disproportionately high for sexual minorities, with 57.4% of bisexual women and 33.5% of lesbian women reporting at least one negative impact (e.g., feeling afraid, missing work, PTSD symptoms), compared to 28.2% of heterosexual women (Walters et al., 2013). For example, hazardous drinking is more common among non-heterosexual survivors (Drabble et al., 2013; Stevens, 2012), and bisexual survivors report greater problem drinking than heterosexual ones (Sigurvinsdottir & Ullman, 2015). Also, greater PTSD symptoms are more likely among bisexual survivors (Long, Ullman, Long, Mason & Starzynski, 2007; Sigurvinsdottir & Ullman, 2015) and lesbians than heterosexual survivors (Sigurvinsdottir & Ullman, 2015). Heterosexual survivors also report fewer depressive symptoms than bisexual women (Sigurvinsdottir & Ullman, 2015). However, data on the psychosocial impact of sexual assault for sexual minorities are seriously lacking, especially longitudinal data, which are needed to understand the recovery process.

Lesbian and bisexual women of color are also at elevated risk for recovery difficulties following victimization. A cross-sectional study of sexual assault survivors found that Black women reported greater depression, PTSD, problem drinking, and drug use than White women and that Black sexual minority women fared worse on these outcomes than Black heterosexual women (Sigurvinsdottir & Ullman, 2015). A recent study of young lesbian and bisexual women recruited through social media found that Asian women reported fewer PTSD symptoms than White women, but there were no race group differences for depression and anxiety (Balsam et al., 2015), confirming other past research (Balsam et al., 2010; Balsam, Beadnell & Molina, 2013). However, other studies have uncovered differences in psychological distress and depression (Bostwick, Hughes, & Johnson, 2005; Kim & Fredriksen-Goldsen, 2012). Given this limited body of research and discrepant findings, further studies are needed to examine the psychological impact of the intersection between race and sexual orientation on recovery from sexual assault over time.

Sexual Assault Revictimization among Sexual and Racial Minorities

Sexual assault survivors may be exposed to multiple victimizations, both in childhood and adulthood. In fact, when women have a CSA history, they are more likely to be assaulted as adults than women without CSA experiences (Walsh et al., 2012). When women have multiple victimization experiences, they report greater recovery problems, such as increased PTSD symptoms (Messman-Moore, Long & Siegfried, 2000). However, revictimization among non-heterosexuals is understudied. In a sample of lesbians and bisexual women, 40% had victimization experiences both as children and adults, and half of the sample met the criteria for hazardous alcohol use (Hequembourg, Livingston & Parks, 2013). In Heidt, Marx, and Gold’s (2005) study of male and female members of the Lesbian/Gay/Bisexual/Transgender (LGBT) community, 63% of the participants reported some kind of lifetime sexual violence. Of those who had been victimized, 38.5% had unwanted experiences both in childhood and adulthood. When revictimized survivors were compared to the other participants, they reported greater depressive symptoms, PTSD symptoms, and psychological distress than those with childhood or adult assault only. Trauma effects may therefore be cumulative across childhood and adulthood, and this accumulation can be connected to adjustment in adulthood (Heidt et al., 2005).

Risk of revictimization is also higher for sexual assault survivors of color with a CSA history, with 27% raped during adolescence and 42% raped as adults (Fargo, 2009). Black women who have had more than one unwanted experience are especially vulnerable to mental health problems, such as PTSD, depression, suicidal ideation, and more (Campbell, Greeson, Bybee, & Raja, 2008). However, to our knowledge, no study has examined the cumulative effects of multiple adult sexual assault experiences while controlling for CSA using a longitudinal design among sexual minority survivors and multiple race groups.

Current Study

The purpose of this study was to examine the recovery trajectories of sexually assaulted women and what role sexual orientation, race, and revictimization play in that recovery. We examined PTSD symptoms and depressive symptoms over three years in a sample of sexually assaulted women. Examining the impact of sexual minority status on survivors’ recoveries is important because little work is available on the topic, particularly using longitudinal designs. Bisexual women appear to be at particularly high risk for recovery problems following sexual assault, so this group needs to be studied further. Also, work examining the intersection of race and sexual orientation in relation to recovery from sexual assault has been scarce. Furthermore, we sought to examine women’s trauma histories to understand whether multiple adult victimizations contribute uniquely to women’s adjustment, beyond the effect of CSA. Previous studies of revictimization in sexual minority women have focused on the effect of child to adult revictimization risk (for example, Heidt et al., 2005). In our study, we examined repeated adult sexual assault (ASA) while controlling for CSA experiences to understand the different roles that these trauma histories play in women’s recovery. Furthermore, there is a clear lack of longitudinal work in this field, making it difficult to examine survivors’ recovery processes. Our hypotheses for this study were the following: 1) Bisexual women will report greater PTSD and depression symptoms than heterosexual women, consistent with previous cross-sectional work on this topic (Sigurvinsdottir & Ullman, 2015); 2) Black women will report greater PTSD and depression symptoms than non-Black women; and 3) Greater history of trauma (revictimization during study and child sexual abuse) will be connected with more PTSD and depression symptoms. The study also had two exploratory goals: to examine recovery trajectories of the groups studied as well as how race and sexual orientation interact to influence psychological symptoms among sexual assault survivors.

Method

Participants

A community sample of bisexual and heterosexual female sexual assault survivors was recruited from a large Midwestern city for three waves of mail surveys (N = 905 for all three waves; original sample N = 1,863). The women ranged in age from 18 to 71 and bisexual women (M = 35.05) were significantly younger than heterosexual women (M = 40.35), t (869) = 3.88, p < 0.001. However, there was no difference in mean age at the time of the assault, 22.12 years for heterosexual women and 21.54 for bisexual women. The sample was ethnically diverse: 47% African-American, 35% White, 2% Asian, 10% other, and 6% multiracial. In this sample, 13% identified as Hispanic, which was assessed separately from race. There were no differences in the racial composition of the sample by sexual orientation. At the first survey, 43% of the women were employed, with no differences by sexual orientation. Most of the sample had low income (71% with annual household incomes of less than $30,000), and bisexual women were likely to have lower incomes than heterosexual women, χ2 (5, N = 866) = 15.62, p = .01. Overall, the women were well-educated: 33% had a college degree or higher, 43% some college education, 15% graduated high-school, and 9% had not completed high school. Half of the sample was single, and half had children.

Eight hundred and ten participants identified as heterosexual and 95 as bisexual. Approximately two-thirds (65.9%) of the sample had experienced CSA, and almost half (49.3%) were victimized at some point during the data collection period. A number of participants (N = 96) identified as one of the following: lesbian; did not provide data on sexual orientation or identified as ‘other’ than heterosexual; bisexual; or lesbian. These women were too heterogeneous in terms of sexual orientation to be combined into one and compared to heterosexual and bisexual survivors. Analysis was not done for the lesbian group (N = 52), because once missing data on key outcomes had been factored in for all waves of data, the group was too small to compare to bisexual and heterosexual women (N = 48). Additionally, previous work has found that bisexual women are at particularly high risk for recovery problems, warranting studies focusing on this group. Unfortunately, we did not have information about whether participants identified as transgender.

Recruitment was accomplished via weekly advertisements in local newspapers, on Craigslist, and through university mass mail. In addition, fliers were posted in the community, at local colleges and universities, as well as at agencies that cater to community members in general and victims of violence against women specifically. Interested women called the research office and were screened for eligibility using the following criteria: a) had an unwanted sexual experience at the age of 14 or older; b) were 18 or older at the time of participation; and c) had previously told someone about their unwanted sexual experience.

Procedure

Participants completed a paid mail survey about their unwanted sexual experiences as part of a study on the impact of sexual assault on adult community-residing women in the Chicago metropolitan area. The mail survey approach was used because it meant women from the local community could participate without potentially revealing themselves as survivors if they had to show up in person at the university. A mail survey was also preferred to a computerized survey, because many of the participants are low-income and may not have had access to a computer. After calling the research office and being screened for eligibility, women were sent packets containing the survey, an informed consent sheet, a list of community resources for dealing with victimization, and a stamped return envelope for the completed survey. At the end of the survey, participants were asked to indicate whether they wanted to continue participating. Those indicating interest in doing more surveys were contacted a year later and sent another survey. Then, a year later, the same procedure was repeated. Participants were sent money orders of $25 in the mail for each survey they completed. The university’s Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures and documents.

Measures

Sexual victimization

Sexual victimization in both childhood (prior to age 14) and adulthood (at age 14 or older) was assessed at all three waves using a modified version of the Sexual Experiences Survey (SES; Koss, Gidycz, & Wisniewski, 1987). The revised measure (Testa, VanZile-Tamsen, Livingston, & Koss, 2004) assesses various forms of sexual assault including: unwanted sexual contact, verbally coerced intercourse, attempted rape, and rape resulting from force or incapacitation (e.g., from alcohol or drugs). The revised 11-item SES measure had good reliability (α = .73); similar reliability was found in our sample (α = .78). Both CSA and ASA were assessed with the SES measure in the wave 1 survey. For the remaining two surveys, participants were asked if they had had an unwanted sexual experience since taking the last survey and completed the SES if that was the case. The SES severity score ranges from 0 = no victimization, 1 = contact, 2 = sexual coercion, 3 = attempted rape, and 4 = rape, but for our longitudinal analyses, we dichotomized the SES at each survey wave (0 = no revictimization, 1 = any type of sexual revictimization).

Posttraumatic stress symptoms

PTSD symptoms were assessed at all three waves with the Posttraumatic Stress Diagnostic Scale (PDS; Foa, 1995), a standardized 17-item instrument based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV (DSM-IV) criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). On a scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (almost always), women rated how often each symptom (i.e., reexperiencing/intrusion, avoidance/numbing, hyperarousal) bothered them in relation to the sexual assault during the past 12 months. If women had more than one assault, PTSD symptoms were assessed with respect to the most serious assault. The PDS has acceptable test–retest reliability for a PTSD diagnosis in assault survivors over two weeks (κ = .74; Foa, Cashman, Jaycox, & Perry 1997). The 17 items were summed to assess the extent of posttraumatic symptomatology (for this sample, wave 1: M = 21.13, SD = 12.93, α = .93; wave 2: M = 16.76, SD = 12.03, α = 0.94; and wave 3: M = 15.41, SD = 12.12, α = .94).

Depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms were measured at all three waves using a 7-item version of the Center of Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CESD-7) modified by Mirowsky and Ross (1990). Participants were asked to rate their symptoms over the past 12 months using a 5-point Likert scale from 0 (never) to 5 (always). In this sample, descriptives for depressive symptoms were: α = .86 (M = 2.01, SD = .75) for wave 1; α = .86 (M = 1.79, SD = 0.75) for wave 2; and α = .88 (M = 1.74, SD = 0.77) for wave 3.

Sexual orientation

Participants were asked at wave 1 whether they identified as mostly heterosexual, somewhat heterosexual, bisexual, somewhat homosexual, or mostly homosexual. This was recoded so that 0 = mostly heterosexual and somewhat heterosexual (810 women) and 1 = bisexual (95 women). This question was created for this study after consulting with an expert on sexual assault in sexual minority women. Those who identified as somewhat homosexual, mostly homosexual or did not provide data were excluded from analysis. This was done because of few lesbians in the sample, especially at wave 3, allowing us to just focus our analyses on bisexual women.

Race

At wave 1, participants were asked to what race they identified. The largest racial group was Black (47%), so analyses of race were done comparing the Black and non-Black groups.

Income

At wave 1, participants were asked to estimate their total household income before taxes. Most were low income, where 71% of participants reported an annual household income of less than $30,000. Income was only used as a control variable to control for social class.

Analysis Strategy

As with most longitudinal studies, it was not possible to get three waves of data from all of the participants. For example, survivors were given the option of dropping out of the study if they wished, or their contact information was no longer accurate when the next survey was mailed to them. For these analyses, only data from participants who completed all three waves was used. This was done because those who did not end up completing waves 2 and 3 of the survey (but stated when they returned the first survey that they wanted to continue participating) were significantly higher on both PTSD and depressive symptoms at wave 1. These participants were therefore removed from the analyses so that they would not increase these outcomes at wave 1 without providing any data for the later time points. Participant dropout did not vary according to sexual orientation or race. We used a hierarchical linear modeling approach in SPSS Version 20 to model the changes in variables over the three waves of data collected. This allowed us to observe changes in the dependent variables over the data collection period, as well as how those trends differed between groups. We modeled the effect of sexual orientation, race, income (control variable), CSA history, and revictimization during the study period. We examined whether wave, race, and revictimization effects varied according to sexual orientation initially by including statistical interaction terms between each of those variables. When the interaction terms were not statistically significant, the effects of combinations of sexual orientation, race, trauma history, and time were not different for subgroups. Thus, we did not retain those nonsignificant interaction terms in the final models for parsimony.

Results

We investigated psychological symptom recovery trajectories in a sample of sexually assaulted women, as well as the role that sexual orientation and trauma histories played in those trajectories. The summarized results from the hierarchical linear model can be seen in Table 1. In our sample, PTSD and depressive symptoms decreased over the three years that data were collected (indicated by the significant negative coefficients for wave).

Table 1.

Predictors of Sexual Assault Recovery

| PTSD | Depression | |

|---|---|---|

| Wave | −1.95** | −0.09** |

| Bisexual | 1.56 | 0.17* |

| Revictimization | 6.74** | 0.27** |

| CSA History | 1.50** | 0.06** |

| Black | −0.35 | −0.08 |

| Income | −0.77** | −0.06** |

| Wave* Black | −1.40** | −0.05* |

| Bisexual* Black | 7.88** | 0.25 |

Note: Coefficients are unstandardized betas.

indicates p < 0.05,

indicates p < 0.001.

The first hypothesis was that bisexual women will report greater PTSD and depression symptoms than heterosexual women. This hypothesis was confirmed, with both depression and PTSD symptoms being significantly higher for bisexual women than for heterosexual women. PTSD symptoms declined an average of 1.95 during each wave for the heterosexual group (mean overall level at wave 1 was 21.13 symptoms). Bisexual women reported on average 1.56 more PTSD symptoms than heterosexual women. There were no significant interactions between time and sexual orientation, so the relationship between sexual orientation and psychological symptoms did not change as time went on. Bisexual women therefore consistently reported greater PTSD and depression symptoms than heterosexual women.

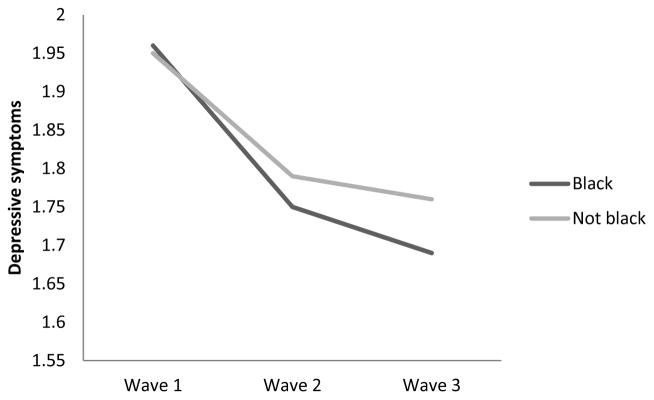

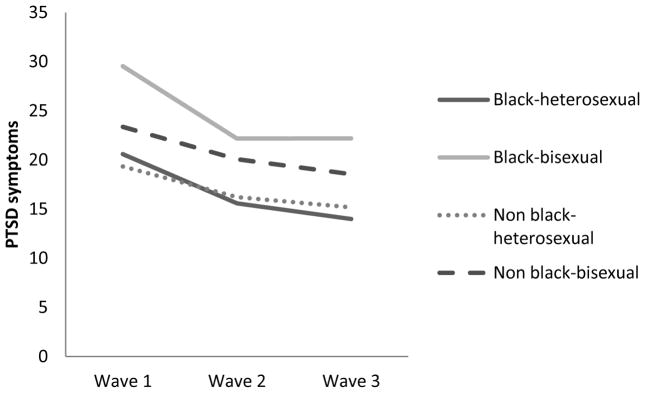

The second hypothesis was that black women will report greater PTSD and depression symptoms than non-Black women. This hypothesis was not confirmed for depression or PTSD symptoms. Figure 1 shows that depression symptoms for Black and non-Black women start out very similar, but symptoms decrease faster among Black women, as evidenced by a significant interaction between wave and race in Table 1. Therefore, the relationship between race and psychological outcomes was different throughout the period of the study. For PTSD symptoms, there was also a significant interaction between time and race, seen in Figure 2 where the non-Black group has a steady decrease in symptoms between each wave, but the Black women have a sharper decline between waves 1 and 2, with a smaller decrease between waves 2 and 3. Additionally, for PTSD symptoms only, there was a significant interaction between race and sexual orientation. Figure 2 shows that Black bisexual women consistently have the highest symptoms, followed by non-Black bisexual women. Heterosexual women of both races have very similar PTSD symptoms throughout the data collection period. Therefore, on its own, race does not significantly contribute to these psychological outcomes, but Black bisexual women report the greatest PTSD symptoms. This shows the importance of examining the intersection between race and orientation when understanding women’s recovery from sexual assault.

Figure 1.

Depressive Symptom Recovery Trajectories by Race

Figure 2.

PTSD Symptom Recovery Trajectories by Race and Sexual Orientation

The third hypothesis was that greater history of trauma (revictimization during study and child sexual abuse) will be connected with more PTSD and depression symptoms. This hypothesis was confirmed; Table 1 shows that revictimization during the data collection period was connected with an increase in 6.74 symptoms for PTSD symptoms and 0.27 symptoms for depression symptoms. Child sexual abuse was also connected with 1.50 more PTSD symptoms and 0.06 depression symptoms. These results show that both of these forms of victimization uniquely contributed to psychological adjustment, even among a sample of adult sexual assault survivors.

These results indicated that overall, psychological symptoms among sexual assault survivors decrease over time. Sexual minority status was connected to increased PTSD and depressive symptoms. However, Black women improved more on depressive symptoms than non-Black women. This was also true for PTSD symptoms, where there was also a significant interaction between race and sexual orientation. Trauma histories also played an important role, because women with a history of CSA or who were revictimized during the study fared worse on these psychological symptom outcomes. These results showed that both CSA and multiple adult victimizations are uniquely connected to increased psychosocial sequelae.

Discussion

Sexual minority women face unique risks in the aftermath of sexual assault, yet little is known about their recovery process. This study was a longitudinal examination of how sexual orientation, race, and revictimization were related to sexual assault survivors’ recovery. The results indicated that in our sample, PTSD and depressive symptoms decreased over a 3-year period among sexual assault survivors. This is a positive finding, but it is possible that the individuals with the greatest risk were lost over time, as they can be more difficult to follow up in a longitudinal study (Scott, Sonis, Creamer & Dennis, 2006), so future studies are needed, particularly in representative samples of victims.

Sexual orientation plays a role in women’s recovery from sexual assault. For both depression and PTSD, bisexual women reported greater symptoms than heterosexual women. Greater psychological sequelae among sexual minorities have also been found in previous cross-sectional studies (Long et al., 2007; Sigurvinsdottir & Ullman, 2015). We also observed that race played a role in the women’s recovery trajectories, in that Black women’s symptoms decreased more over time, both for PTSD and depression. Additionally, for PTSD we observed an interaction of bisexual orientation and race, whereby Black bisexual women fared by far the worst of all on these symptoms. These results underscore the importance of examining race and sexual orientation together in studies of sexual assault recovery in women.

Trauma history was also connected with psychological symptoms. We found that women who had been revictimized during the 3-year study reported greater problems than those who had not. This effect remained when CSA history was controlled for, which also contributed to greater symptoms, consistent with previous literature on the topic (Ullman et al., 2005; Ullman et al., 2009). These results suggest that multiple sexual victimizations in adulthood therefore have additive effects in terms of survivor psychological outcomes. We also examined whether recovery trajectories were impacted by adult revictimization experiences and did not find that to be the case. Survivors therefore have greater psychological symptoms when they have had multiple experiences, but the trends in recovery do not differ significantly from those only victimized as adults before the start of the survey. Interventions or strategies that target survivors with multiple traumas therefore may need to be more intensive than the current standard, but it might not be necessary to completely alter those approaches for this population.

These results highlight the importance of examining the recovery of sexual assault survivors longitudinally, because survivors’ psychological symptoms may change significantly over time, and how that happens is important for understanding their well-being and developing interventions to help them. Recovery from sexual assault and related psychosocial consequences can be a long and difficult process, which is important to understand in detail. Current studies of trajectories of recovery have not examined sexual orientation, but have shown that distinct subgroups (Rothbaum, Foa, Riggs, Murdock & Walsh, 1992; Steenkamp, Dickstein, Salters-Pedneault, Hofmann & Litz, 2012) exist, so similar analyses are needed for sexual minority women.

These results also show the importance of examining the context of women’s lives in shaping their experiences. For example, both race and sexual orientation seem to play a role in how women recover from an unwanted sexual experience. In terms of sexual orientation, minority stress has been suggested as a possible explanation for the elevated psychological problems among non-heterosexual sexual assault survivors. In this way, stress associated with living in a homophobic society can contribute to greater problems among this population (DiPlacido, 1998). In our study, we compared heterosexual and bisexual women; the latter group may be at even greater risk for stress and recovery problems because of marginalization from the straight community (Weber, 2008). Furthermore, bisexual women may experience further stress because the group is more heterogeneous and less visible as a community (Israel & Mohr, 2004). Unfortunately, we do not have measures of minority stress in this study, but our data clearly show the unique needs of bisexual women, who may need specialized resources to address unwanted sexual experiences. Clinicians need to be aware that sexual victimization may not only be more prevalent for sexual minority women but also lead to more severe psychological consequences. Given that CSA is more prevalent for sexual minority women and affects their depression and PTSD symptoms even beyond other adult victimization, prevention efforts are needed to target and treat effects of CSA in sexual minority women.

The race of the survivor was also connected to worse psychological symptoms for bisexual women, suggesting that women who are at the intersection of race and sexual orientation face unique challenges and prejudices that can make their recovery more challenging. This type of multiple marginalization is consistent with previous work showing the compounded effects of sexual and racial prejudice (Bowleg, Huang, Brooks, Black, & Burkholder, 2003). Part of this discrimination may come from homophobia in communities of color (Balsam, Molina, Beadnell, Simoni, & Walters, 2011; Chae et al., 2010; Mays, Cochran, & Rhue, 1993) or racism in LGB communities (Balsam et al., 2011; Chae et al., 2010; Ward, 2008). Professionals should be trained to take a full history of clients’ trauma experiences and associated sequelae, talk with women about how their symptoms may relate to assault histories in the context of their sexuality, and provide trauma-specific treatments to address their needs (see Vickerman & Margolin [2009] for a review).

Limitations of this study include the use of a convenience sample and that participants in the sample overwhelmingly identified as heterosexual, decreasing power of the analyses. Also, because we mailed surveys to participants, those who did not have a permanent address may have dropped out of the study. This may have resulted in the loss of the highest risk participants from our sample. Indeed, we only analyzed data from participants with complete data, thus losing those who reported greater depression and PTSD symptoms at wave 1. Also, because the sample is non-representative, it cannot fully illuminate how race and sexual orientation are both connected with psychological adjustment. This possibility speaks to the difficulty of conducting longitudinal studies with community samples, especially with groups that have multiple stressors in their lives. It is important to note, however, that dropout during the study did not affect the results, as we only used data from participants completing all three waves.

In future work, family violence researchers need representative samples of female victims followed for a longer period of time with larger, ethnically diverse subsamples of sexual minority women to see if these results can be replicated. Also, sexual minority stress needs to be measured longitudinally along with various recovery outcomes that go beyond psychological symptom measures to include broader psychosocial adjustment outcomes. Clinical assessment and treatment should focus attention on Black bisexual survivors who appear to be at particularly greater risk of poorer recovery outcomes. Finally, intersections of sexual forms of victimization with other forms of family violence (e.g., physical and emotional forms of both partner abuse and child abuse) are needed in order to elucidate the roles of race and sexual orientation. Such research will help researchers and practitioners better understand psychological impact and treatment needs of multiply traumatized, marginalized women who are currently underserved.

Acknowledgments

The research was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism grant R01 #17429 to Sarah E. Ullman. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIAAA.

The authors would like to acknowledge Mark Relyea, Cynthia Najdowski, Liana Peter-Hagene, Amanda Vasquez, Meghna Bhat, Rene Bayley, Gabriela Lopez, Farnaz Mohammad-Ali, Saloni Shah, Susan Zimmerman, Diana Acosta, Shana Dubinsky, Brittany Tolar, Hira Rehman, Joanie Noble, Sabina Skupien, Nava Lalehzari, Justyna Ciechonska, and Edith Zarco for assistance with data collection.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflict of interests and the findings have not been published in other journals.

References

- Abbey A, Jacques-Tiaura A, Parkhill M. Sexual assault among diverse populations of women: Common ground, distinctive features, and unanswered questions. In: Russo NF, Landrine H, editors. Handbook of Diversity in Feminist Psychology. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 2010. pp. 391–425. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Amodeo M, Griffin ML, Fassler IR, Clay CM, Ellis MA. Childhood sexual abuse among Black women and White women from two-parent families. Child Maltreatment. 2006;11(3):237–246. doi: 10.1177/1077559506289186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arreola SG, Neilands TB, Pollack LM, Paul JP, Catania JA. Higher prevalence of childhood sexual abuse among Latino men who have sex with men than non-Latino men who have sex with men: Data from the Urban Men’s Health Study. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2005;29(3):285–290. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsam KF, Beauchaine TP, Rothblum ED. Victimization Over the Life Span: A Comparison of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Heterosexual Siblings. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73(3):477–487. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsam KF, Beadnell B, Molina Y. The Daily Heterosexist Experiences Questionnaire: Measuring minority stress among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender adults. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling & Development. 2013;46:3–25. doi: 10.1177/0748175612449743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsam KF, Lehavot K, Beadnell B, Circo E. Childhood abuse and mental health indicators among ethnically diverse lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78(4):459–468. doi: 10.1037/a0018661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsam KF, Molina Y, Beadnell B, Simoni J, Walters K. Measuring multiple minority stress: The LGBT People of Color Microaggressions Scale. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2011;17(2):163–174. doi: 10.1037/a0023244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsam KF, Molina Y, Blayney JA, Dillworth T, Zimmerman L, Kaysen D. Racial/Ethnic Differences in Identity and Mental Health Outcomes Among Young Sexual Minority Women. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2015 doi: 10.1037/a0038680. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black MC, Basile KC, Breiding MJ, Smith MJ, Walters SG, Merrick MT, Stevens MR. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 summary report. 2011 Retrieved from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/nisvs/

- Bostwick WB, Hughes TL, Johnson T. The co-occurrence of depression and alcohol dependence symptoms in a community sample of lesbians. Journal of Lesbian Studies. 2005;9(3):7–18. doi: 10.1300/J155v09n03_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L, Huang J, Brooks K, Black A, Burkholder G. Triple jeopardy and beyond: Multiple minority stress and resilience among Black lesbians. Journal of Lesbian Studies. 2003;7(4):87–108. doi: 10.1300/J155v07n04_06. 2003787108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant-Davis T, Ullman SE, Tsong Y, Tillman S, Smith K. Struggling to survive: Sexual assault, poverty, and mental health outcomes of African American women. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2010;80(1):61–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01007.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell R, Dworkin E, Cabral G. An ecological model of the impact of sexual assault on women’s mental health. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse. 2009;10:225–246. doi: 10.1177/1524838009334456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell R, Greeson MR, Bybee D, Raja S. The co-occurrence of childhood sexual abuse, adult sexual assault, intimate partner violence, and sexual harassment: A mediational model of posttraumatic stress disorder and physical health outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76(2):194–207. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.194. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chae DH, Krieger N, Bennett GG, Lindsey JC, Stoddard AM, Barbeau EM. Implications of discrimination based on sexuality, gender, and race/ethnicity for psychological distress among working-class sexual minorities: The United for Health Study, 2003–2004. International Journal of Health Services. 2010;40(4):589–608. doi: 10.2190/HS.40.4.b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiPlacido J. Minority stress among lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals: A consequence of heterosexism, homophobia and stigmatization. In: Herek G, editor. Stigma and Sexual Orientation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. pp. 138–159. [Google Scholar]

- Drabble L, Trocki KF, Hughes TL, Korcha RA, Lown AE. Sexual Orientation Differences in the Relationship Between Victimization and Hazardous Drinking Among Women in the National Alcohol Survey. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2013;27(3):639–648. doi: 10.1037/a0031486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar E. Race, gender, and sexual orientation in hate crime victimization: Identity politics or identity risk? Violence and Victims. 2006;21(3):323–337. doi: 10.1891/vivi.21.3.323. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1891/vivi.21.3.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fargo JD. Pathways to adult sexual revictimization: Direct and indirect behavioral risk factors across the lifespan. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2009;24(11):1771–1791. doi: 10.1177/0886260508325489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB. Posttraumatic Stress Diagnostic Scale manual. Minneapolis: National Computer Systems; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Cashman L, Jaycox L, Perry K. The Validation of a Self-Report Measure of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: The Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale. Psychological Assessment. 1997;9(4):445–451. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman MS, Marshal MP, Guadamuz TE, Wei C, Wong CF, Saewyc E, et al. A meta-analysis of disparities in childhood sexual abuse, parental physical abuse, and peer victimization among sexual minority and sexual nonminority individuals. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101(8):1481–1494. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.190009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidt JM, Marx BP, Gold SD. Sexual revictimization among sexual minorities: A preliminary study. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2005;18(5):533–540. doi: 10.1002/jts.20061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hequembourg AL, Livingston JA, Parks KA. Sexual victimization and associated risks among lesbian and bisexual women. Violence Against Women. 2013;19(5):634–657. doi: 10.1177/1077801213490557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes T, McCabe SE, Wilsnack SC, West BT, Boyd CJ. Victimization and substance use disorders in a national sample of heterosexual and sexual minority women and men. Addiction. 2010;105(12):2130–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03088.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel T, Mohr JJ. Attitudes towards bisexual women and men: Current research, future directions. Journal of Bisexuality. 2004;4(1–2):117–134. doi: 10.1300/J159v04n01_09. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS, Ruggiero KJ, Conoscenti LM, McCauley J. Drug-facilitated, incapacitated, and forcible rape: A national study. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice; 2007. National Institute of Justice Publication No. NCJ 219181. [Google Scholar]

- Kim HJ, Fredriksen-Goldsen KI. Hispanic lesbians and bisexual women at heightened risk for [corrected] health disparities. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102:e9–e15. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Gidycz CA, Wisniewski N. The scope of rape: Incidence and prevalence of sexual aggression and victimization in a national sample of students in higher education. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1987;55(2):162–170. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.55.2.162. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.55.2.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebs CP, Lindquist CH, Barrick K. The Historically Black College and University Campus Sexual Assault (HBCUCSA) Study. 2011 Retrieved from the National Criminal Justice Reference Service: www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/233614.pdf.

- Long SM, Ullman SE, Long LM, Mason GE, Starzynski LL. Women’s Experiences of Male-Perpetrated Sexual Assault by Sexual Orientation. Violence and Victims. 2007;22(6):684–701. doi: 10.1891/088667007782793138. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1891/088667007782793138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mays VM, Cochran SD, Rhue S. The impact of perceived discrimination on the intimate relationships of black lesbians. Journal of Homosexuality. 1993;25(4):1–14. doi: 10.1300/J082v25n04_01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messman-Moore TL, Long PJ, Siegfried NJ. The revictimization of child sexual abuse survivors: An examination of the adjustment of college women with child sexual abuse, adult sexual assault and adult physical abuse. Child Maltreatment. 2000;5(1):18–27. doi: 10.1177/1077559500005001003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Identity, stress, and resilience in lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals of color. The Counseling Psychologist. 2010;38(3):442–454. doi: 10.1177/0011000009351601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirowsky J, Ross CE. Control or defense? Depression and the sense of control over good and bad outcomes. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1990;31:71–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JF, Balsam KF. Lesbian and Bisexual Women’s Experiences of Victimization: Mental Health, Revictimization, and Sexual Identity Development. Journal of Lesbian Studies. 2003;7(4):67–85. doi: 10.1300/J155v07n04_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs. Hate violence against the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer communities in the United States in 2009. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.avp.org/documents/NCAVP2009HateViolenceReportforWeb.pdf.

- Roberts AL, Austin SB, Corliss HL, Vandermorris AK, Koenen KC. Pervasive trauma exposure among U.S. sexual orientation minority adults and risk of post-traumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(12):2433–2441. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.168971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbaum BO, Foa EB, Riggs DS, Murdock T, Walsh W. A prospective examination of post-traumatic stress disorder in rape victims. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1992;5(3):455–475. doi: 10.1002/jts.2490050309. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman EF, Exner D, Baughman AL. The Prevalence of Sexual Assault Against People Who Identify as Gay, Lesbian or Bisexual in the United States: A Systematic Review. Trauma, Violence & Abuse. 2011;12(2):55–66. doi: 10.1177/1524838010390707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott C, Sonis J, Creamer M, Dennis M. Maximizing follow-up in longitudinal studies of traumatized populations. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2006;19(6):757–769. doi: 10.1002/jts.20186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigurvinsdottir R, Ullman SE. The role of sexual orientation in the victimization and recovery of sexual assault survivors. Violence and Victims. 2015;30:636–648. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.VV-D-13-00066. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.VV-D-13-00066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steenkamp MM, Dickstein BD, Salters-Pedneault K, Hofmann SG, Litz BT. Trajectories of PTSD symptoms following sexual assault: Is resilience the modal outcome? Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2012;25(4):469–474. doi: 10.1002/jts.21718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens S. Meeting the substance abuse treatment needs of lesbian, bisexual and transgender women: implications from research to practice. Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation. 2012;3(Suppl 1):27–36. doi: 10.2147/SAR.S26430. Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.2147/SAR.S26430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temple JR, Weston R, Rodriguez BF, Marshall LL. Differing effects of partner and nonpartner sexual assault on women’s mental health. Violence Against Women. 2007;13:285–297. doi: 10.1177/1077801206297437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, VanZile-Tamsen C, Livingston JA, Koss MP. Assessing women’s experiences of sexual aggression using the Sexual Experiences Survey: Evidence for validity and implications for research. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2004;28(3):256–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2004.00143.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Extent, nature, and consequences of rape victimization: Findings from the National Violence Against Women Survey [NCJ 210346] Retrieved from the National Criminal Justice Reference Service; 2006. https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/210346.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, Filipas HH, Townsend SM, Starzynski L. Trauma exposure, PTSD, and problem drinking among sexual assault survivors. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66(5):610–619. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.610. http://dx.doi.org/10.15288/jsa.2005.66.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, Najdowski CJ. Revictimization as a moderator of psychosocial risk factors for problem drinking in female sexual assault survivors. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;70(1):41–49. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.41. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2009.70.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vickerman K, Margolin G. Rape treatment outcome research: Empirical findings and state of the literature. Clinical Psychology Review. 2009;29(5):431–448. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh K, Kmett Danielson C, McCauley JL, Saunders BE, Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS. National prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder among sexually revictimized adolescent, college, and adult household-residing women. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2012;69(9):935–942. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters ML, Chen J, Breiding MJ. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 Findings on Victimization by Sexual Orientation. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ward J. White normativity: The cultural dimensions of Whiteness in a racially diverse LGBT organization. Sociological Perspectives. 2008;51(3):563–586. doi: 10.1525/sop.2008.51.3.563. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weber GN. Using to numb the pain: substance use and abuse among lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. Journal of Mental Health Counseling. 2008;30(1):31–48. [Google Scholar]

- West Carolyn M. Battered, Black, and Blue: An Overview of Violence in the Lives of Black Women. Women and Therapy. 2002;25(3/4):5–27. doi: 10.1300/J015v25n03_02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- West C. Sexual Violence in the Lives of African American Women. Harrisburg, PA: VAWnet, a project of the National Resource Center on Domestic Violence; 2013. Mar, Available at: http://www.vawnet.org. [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt G. The sociocultural context of African American and White American women’s rape. Journal of Social Issues. 1992;48m:77–91. [Google Scholar]