1. Introduction

The extinct Devonian placoderms (armoured jawed fishes) [1,2] are central to the question of tooth origins, because some have denticulate ‘toothplates’ within the mouth cavity. A key question is whether these gnathal plates were modified from external dermal bones, or had ‘denticles’ representing true teeth with pulp cavities [3, fig. 2h]. The recent contribution by Rücklin & Donoghue [4] confuses this issue, because their claimed ‘anterior supragnathal’ (ASG) of the placoderm Romundina stellina shows no evidence that it came from the oral cavity, and is more likely an external dermal element. Also, the tissue identified as enameloid is not birefringent and thus not enameloid. Their inferences about growth of toothplates, phylogenetic loss of enameloid, and independent development of teeth and jaws, based on the structure of this plate, are therefore invalid.

2. Gnathal plate or dermal armour?

The supposed ‘ASG’ came from “residues associated with the holotype of R. stellina” [4], but Ørvig [5] had asserted there were no gnathal elements in the type residues. Subsequent collections from the type locality contain numerous similar elements, and one articulated specimen with ASGs preserved in position [4, fig. 1a], as previously figured [6,7]. This ‘undetermined acanthothoracid’ [7] has the same dermal skull ornament of stellate tubercles as Romundina [5], but is a new taxon (cf. [4,6]) because the bone pattern is different. Its articulated ASGs have embayed posterior margins, and ornament of mainly elongate denticles with the smallest in the depressed central part [7, fig. 3a], representing the ossification centre as in typical supragnathal elements from the Early Devonian ([7–9]; figure 1). By contrast, the supposed ASG has convex margins [4], and the central (stellate) tubercle is largest and highest. Although it was claimed that “surface morphology of the tubercles … is quite distinct from … the dermal tubercles” [4], the latter are variable in R. stellina [5,10]; stellate tubercles on a typical small dermal plate (figure 2a) differ mainly from the supposed ASG in having more radiating ridges. We suggest the supposed ‘teeth’ are only dermal tubercles. Growth of the plate, by marginal addition without resorption, is normal for dermal platelets and scales [10, p. 207].

Figure 1.

Early Devonian arthrodire ANU V244, specimen previously figured [8,9]: three-dimensional prototype of right anterior supragnathal (a) in position, ventral view; (b) depressed cancellous upper surface (att.) for braincase attachment. (Online version in colour.)

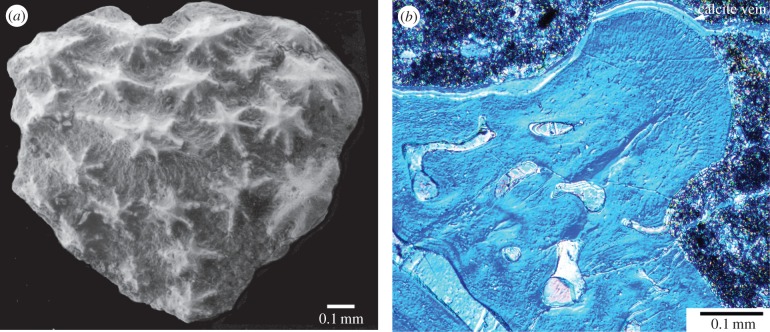

Figure 2.

Romundina cf. stellina from Romundina type locality, Drake Bay Formation, Prince of Wales Island, Arctic Canada (Natural History Museum Paris collection). (a) Small plate DB4-95-1 [10, fig. 3a: ‘scale’]. (b) Vertical section through tubercle on spinal plate DB4-95-4 under crossed polars with DIC filters. (Online version in colour.)

The supposed ASG was compared with the much younger (Late Devonian) derived arthrodire Compagopiscis, despite its different morphology [4, fig. 1f–h]. However, described Early Devonian arthrodire gnathals ([8,9]; not cited in [4]) all have a concave cancellous inner surface (figure 1b) for attachment to perichondral bone, completely unlike the convex lamellar bone inner surface on the supposed ASG [4]. External shape, tubercle type and overall morphology demonstrate that this element is not a gnathal bone; possibly it came from the mosaic of small ornamented plates in the Romundina ventral armour [7].

3. Histological interpretation

The tubercles, described as “multi-cuspid teeth, each composed of an enameloid cap and core of dentine” [4, p. 1], actually have enclosed cell spaces and no pulp cavity, thus demonstrating the special placoderm tissue ‘semidentine’, as in Romundina dermal tubercles ([5,11]; figure 2b). This histology is very different from typical tooth ‘orthodentine’, with no sign of the distinct pulp cavities seen in the derived arthrodire Compagopiscis [4, fig. 2e]. Also, the supposed enameloid layer, a zone densely filled with semidentine tubules perpendicular to the surface [11, fig. 41], shows no evidence of crystallites that would indicate enameloid; thin sections (figure 2b) show it is not birefringent. As enameloid cannot be demonstrated in Romundina, there is no support for the conclusion that enameloid was lost in other placoderms.

Acknowledgements

We thank Daniel Goujet (Paris) for advice, Tim Senden and Michael Turner (RSPE) for XCT scanning, and three anonymous referees for comments.

Footnotes

The accompanying reply can be viewed at http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2016.0526.

Data accessibility

Data is available from the Dryad Repository (http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.9n237) [12].

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally.

Competing interests

We have no competing interests.

Funding

This study is funded by Australian Research Council DP1092870 to G.Y.

References

- 1.Young GC. 2010. Placoderms (armored fish): dominant vertebrates of the Devonian Period. Ann. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 38, 523–550. ( 10.1146/annurev-earth-040809-152507) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goujet DF. 2015. Placodermi (Armoured Fishes). In eLS. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith MM, Johanson Z. 2003. Separate evolutionary origins of teeth from evidence in fossil jawed vertebrates. Science 299, 1235–1236. ( 10.1126/science.1079623) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rücklin M, Donoghue PCJ. 2015. Romundina and the evolutionary origin of teeth. Biol. Lett. 11, 20150326 ( 10.1098/rsbl.2015.0326) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ørvig T. 1975. Description, with special reference to the dermal skeleton, of a new radotinid arthrodire from the Gedinnian of arctic Canada. Colloques Int. CNRS 218, 41–71. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith MM, Johanson Z. 2003. Response to comment on ‘Separate evolutionary origins of teeth from evidence in fossil jawed vertebrates’. Science 300, 1661c. ( 10.1126/science.1084686) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goujet D, Young GC. 2004. Placoderm anatomy and phylogeny: new insights. In Recent advances in the origin and early radiation of vertebrates (eds Arratia G, Wilson MVH, Cloutier R), pp. 109–126. München, Germany: Pfeil. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Young GC, Lelièvre H, Goujet D. 2001. Primitive jaw structure in an articulated brachythoracid arthrodire (placoderm fish; Early Devonian) from southeastern Australia. J. Vert. Paleontol. 21, 670–678. ( 10.1671/0272-4634(2001)021[0670:PJSIAA]2.0.CO;2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Young GC. 2003. Did placoderm fish have teeth? J. Vert. Paleontol. 23, 987–990. ( 10.1671/31) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burrow CJ, Turner S. 1999. A review of placoderm scales, and their relevance in placoderm phylogeny. J. Vert. Paleontol. 19, 204–219. ( 10.1080/02724634.1999.10011135) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ørvig T. 1980. Histologic studies of Ostracoderms, Placoderms and Fossil Elasmobranchs: 4. Ptyctodontid tooth plates and their bearing on holocephalan ancestry: the condition of Ctenurella and Ptyctodus . Zool. Scripta 9, 219–239. ( 10.1111/j.1463-6409.1980.tb00665.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burrow C, Hu Y, Young G. 2016. Data from: Placoderms and the evolutionary origin of teeth. Dryad Digital Repository. ( 10.5061/dryad.9n237) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available from the Dryad Repository (http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.9n237) [12].