Abstract

Invasive species may impact pathogen transmission by altering the distributions and interactions among native vertebrate reservoir hosts and arthropod vectors. Here, we examined the direct and indirect effects of the red imported fire ant (Solenopsis invicta) on the native tick, small mammal and pathogen community in southeast Texas. Using a replicated large-scale field manipulation study, we show that small mammals were more abundant on treatment plots where S. invicta populations were experimentally reduced. Our analysis of ticks on small mammal hosts demonstrated a threefold increase in the ticks caught per unit effort on treatment relative to control plots, and elevated tick loads (a 27-fold increase) on one common rodent species. We detected only one known human pathogen (Rickettsia parkeri), present in 1.4% of larvae and 6.7% of nymph on-host Amblyomma maculatum samples but with no significant difference between treatment and control plots. Given that host and vector population dynamics are key drivers of pathogen transmission, the reduced small mammal and tick abundance associated with S. invicta may alter pathogen transmission dynamics over broader spatial scales.

Keywords: ecology, species interactions, vector, invasive species, tick-borne pathogens

1. Introduction

Invasive species can directly or indirectly alter vector-borne disease systems by changing the abundance of, or interactions between, vectors and their hosts. Previous studies have most commonly implicated the invader in altering species relationships in ways that support vector-borne pathogen transmission and, therefore, increase disease risk. For example, a widespread, invasive shrub increases human risk of ehrlichiosis because it provides habitat for deer that host infected ticks [1], and densities of ticks and tick hosts were greatest in areas that had been invaded by the causative agent of sudden oak death [2]. By contrast, with few exceptions (e.g. [3]), invasive species have less frequently been implicated in the reduction of infectious disease transmission. However, invasive host species may dilute vector-borne disease risk consistent with the dilution effect hypothesis [4]. For example, infection of native mice with flea-transmitted Bartonella species was reduced with increasing densities of introduced voles [5].

Here, we investigate the potential impact of the invasive red imported fire ant (Solenopsis invicta) on tick, small mammal and pathogen communities in southeast Texas. Ticks and small mammals transmit and maintain numerous zoonotic pathogens that are significant public health concerns. Solenopsis invicta are known to predate small mammals [6], and their presence is associated with changes in mammal foraging activity [7] and habitat selection [8] possibly mediated by changes in food resources [9]. Solenopsis invicta are also associated with reductions in tick populations [10,11], although effects vary between tick species [10]. Using a large-scale manipulative experiment to reduce S. invicta populations across an area of historic invasion, we expected that S. invicta predation and avoidance behaviour by mammals and ticks would lead to decreased mammal, tick and pathogen abundance in plots where S. invicta were in high density relative to treatment plots where S. invicta were experimentally suppressed.

2. Material and methods

The manipulative experiment occurred at two field sites separated by over 160 km in southeast Texas: Attwater Prairie Chicken National Wildlife Refuge (APCNWR) and a private ranch in Goliad County (GRR). Each field site was partitioned into two treatment plots and two control plots. Treatment plots were chemically treated with Extinguish Plus™ (Central Life Sciences, Schaumburg, IL, USA) for S. invicta suppression as part of an existing management plan for Attwater's prairie-chicken (Tympanuchus cupido attwateri) [12]; control plots were not treated. Efficacy of the treatment was monitored by setting out fatty lures in treatment and control plots ([12]; see the electronic supplementary material).

Small mammals and their attached ticks were collected using seed-baited Sherman live traps (H.B. Sherman Traps, Tallahassee, FL, USA). Three line transects (approx. 20 m apart), each with 20 traps spaced 10 m apart, were spread across each of the four plots at both field sites, resulting in a total of 60 traps per plot and 240 traps per site. Small mammal trapping was conducted for two consecutive nights each month (APCNWR: trapping occurred from June 2013 until September 2014; GRR: October 2013 until July 2014, with the exception of January 2014). All captured mammals were marked with an ear tag, identified to species and inspected for ticks, which were removed, identified and stored in 70% ethanol. Off-host tick presence was assessed via drag sampling (see the electronic supplementary material). On-host ticks were tested for infection with microbes in the genera Rickettsia and Borrelia (see the electronic supplementary material).

We used general linear mixed models assuming a negative binomial error distribution to analyse counts of mammals and on-host ticks across treatment and control plots. We used a zero-inflated (ZI) model if it fit the data better (i.e. lower Akaike information criteria) than the same model that did not account for ZI. All models were implemented in program R (v. 3.2.2) in the package glmmADMB (v. 0.8.3.2). Site (two levels, APCNWR and GRR) and season (four levels, spring = March to May; summer = June to August; autumn = September to November; winter = December to February) were added to models as random intercepts (mammal abundance was spatio-temporally heterogeneous throughout the study; see the electronic supplementary material). Sampling effort (effective trap nights) per transect was included in the model using the offset function. Significance of all treatment coefficients was assessed through a log-likelihood ratio test of nested models assuming a χ2-distribution. Association between pathogen infection of ticks (larval pools, larval individuals, and nymphs analysed separately) and S. invicta treatment was tested with a Fisher's exact test.

3. Results

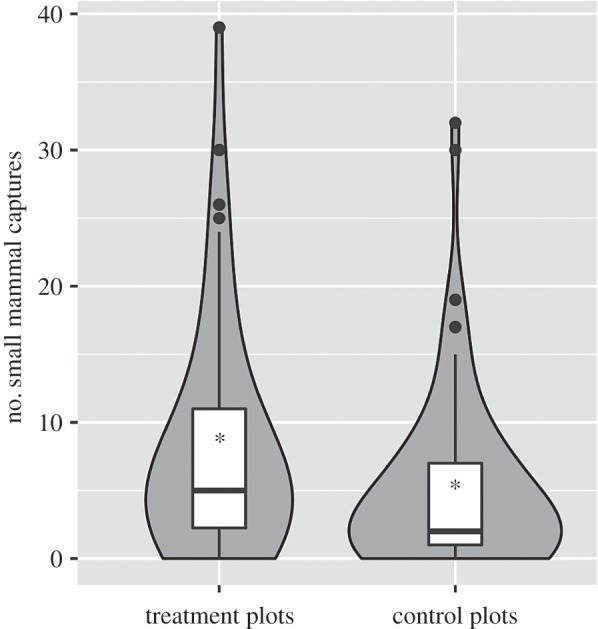

The majority (64.1%) of small mammals captured were from S. invicta-suppressed treatment plots (table 1; figure 1; electronic supplementary material, figure 1). Our model predicted a 1.8-fold increase in the total number of small mammals captured per unit effort on treatment relative to control plots (p < 0.001). The effect was consistent among the three most commonly sampled mammal species (Sigmodon hispidus, Baiomys taylori and Reithrodontomys fulvescens). Our model predicted a 2.0-fold increase in S. hispidus captured on treatment relative to control plots (p < 0.001). Effect sizes were slightly lower for B. taylori (1.4-fold increase on treatment plots, p = 0.01) and R. fulvescens (1.4-fold increase on treatment plots, p = 0.05).

Table 1.

Mammal captures presented by species and plot type at both Attwater Prairie Chicken National Wildlife Refuge (APCNWR) and a private ranch in Goliad County, Texas (GRR). (Number of captures and percentage of total captures per site (in parentheses) are indicated for each species across site and plot type. Treatment plots are those that were treated with Extinguish Plus™ to suppress red imported fire ants.)

| species | APCNWR treatment | APCNWR control | GRR treatment | GRR control | total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sigmodon hispidus (hispid cotton rat) | 354 (68.5%) | 163 (31.5%) | 11 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 528 |

| Baiomys taylori (northern pygmy mouse) | 127 (62.0%) | 78 (38.0%) | 107 (65.6%) | 56 (34.4%) | 368 |

| Reithrodontomys fulvescens (fulvous harvest mouse) | 69 (51.9%) | 64 (48.1%) | 63 (84.0%) | 12 (16.0%) | 208 |

| Chaetodipus hispidus (hispid pocket mouse) | 12 (42.9%) | 16 (57.1%) | 9 (56.3%) | 7 (43.7%) | 44 |

| Peromyscus leucopus (white-footed mouse) | 0 (0%) | 27 (100%) | 10 (90.9%) | 1 (9.1%) | 38 |

| Cryptotis parva (least shrew) | 0 (0%) | 1 (100%) | 6 (66.7%) | 3 (33.3%) | 10 |

| Perognathus merriami (Merriam's pocket mouse) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (100%) | 1 |

| Oryzomys palustris (marsh rice rat) | 0 (0%) | 1 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 |

| total | 562 | 350 | 206 | 80 | 1198 |

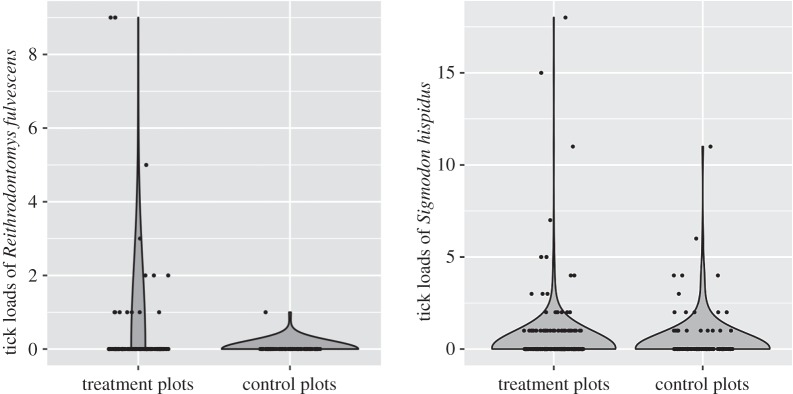

Figure 1.

A violin/box plot hybrid demonstrating the number of small mammal captures on treatment and control plots. Asterisks denote means.

Ninety-eight mammals (8.7% of captures) were parasitized by a total of 237 ticks, including 142 larvae and 95 nymphs (electronic supplementary material, tables S2 and S3). Nearly all ticks were Ambylomma maculatum (99.6%) with the exception of one nymphal Ixodes scapularis (0.4%). The rodent species most heavily parasitized by ticks were S. hispidus (15.6% of total captures), Chaetodipus hispidus (7.7%), R. fulvescens (7.7%) and B. taylori (1.4%). Our model predicted a threefold increase in the number of on-host ticks caught per unit effort on treatment relative to control plots (p = 0.01). When the number of rodents captured during a sampling night was included in the model with the offset function, the model still predicted an increase in the number of ticks on treatment plots, but this effect was no longer significant (p = 0.45). This suggests that the effect of a greater number of on-host ticks on treatment plots was primarily driven by an increased capture rate of small mammals along treatment transects. To directly investigate tick loads across treatment and control plots, we modelled the number of ticks per host individual in S. hispidus and R. fulvescens, two well-sampled (N = 482 and 195, respectively) and highly parasitized species in our data. Tick loads did not vary significantly across plots in S. hispidus (p = 0.90, figure 2), possibly due to demographic effects that resulted after an explosive increase in the population (see the electronic supplementary material). However, our model predicted a 27-fold increase in the tick loads on R. fulvescens on treatment relative to control plots (p = 0.003; figure 2). Drag sampling of 30 200 m2 of vegetation resulted in the collection of 86 ticks, with no difference between treatment and control plots (see the electronic supplementary material).

Figure 2.

A violin plot demonstrating the probability density of tick loads on two species of small mammals. Dots represent actual observations, jittered horizontally to better demonstrate sample sizes.

A total of 126 individual tick nymphs and larval pools removed from mammals were tested for infection with Rickettsia species, of which 34 (27.0%) tested positive (electronic supplementary material, table S4). Most rickettsial sequences had high homology to species regarded as endosymbionts (n = 27; electronic supplementary material, table S4). A total of seven A. maculatum samples were infected with the human pathogen R. parkeri (1.4% prevalence in larvae and 6.7% prevalence in nymphs). The proportion of ticks infected with R. parkeri was not different between treatment and control plots (p > 0.05). A total of 83 tick samples were tested for infection with Borrelia species of which B. lonestari was found in a single A. maculatum nymph on an APCNWR treatment plot (electronic supplementary material, table S4).

4. Discussion

The invasion of red imported fire ants in the southern United States has had large, negative consequences on ecological communities (reviewed in [13]). We observed decreased small mammal abundances in the presence of S. invicta (figure 1), possibly associated with direct (e.g. predation) and indirect effects (e.g. changes in habitat selection and avoidance behaviour) [7,8]. Furthermore, we observed that increased small mammal populations on S. invicta-suppressed plots were associated with an increased abundance of on-host ticks (figure 2), consistent with host population regulation of tick populations [14]. Our data suggest that S. invicta reduce small mammal populations that, in turn, regulate local tick populations. Thus, these invasive ants may influence tick abundance by affecting the behavioural or physiological mechanisms that control the number of ticks on host individuals, although tick populations may also be influenced directly by S. invicta predation. However, the collection of off-host ticks by drag sampling, which was largely restricted to the adult life stage, was not significantly different between control and treatment plots (see the electronic supplementary material). Notably, our study did not investigate other potentially important hosts that support ticks at the larval and nymph stage (i.e. small ground passerines), or adult-stage ticks (i.e. larger mammals), which may also affect tick abundance. It is possible that lower small mammal abundance could increase the frequency of ticks feeding on alternative hosts, including humans, thus increasing disease risk (e.g. [15]).

The cascading effects of S. invicta on native small mammal and tick populations have important potential implications for the transmission of tick-borne pathogens, which represent significant public health concerns. Small mammals such as S. hispidus, which was heavily parasitized in this study, are reservoirs for numerous tick-borne pathogens including those in the genera Borrelia, Rickettsia, Anaplasma and Babesia, as well as multiple viruses [16]. Increased small mammal and tick abundance in S. invicta-suppressed areas are expected to intensify contact rates between ticks and hosts, facilitating pathogen transmission. Indeed, increasing host abundance is one of the main drivers of tick-borne disease emergence [17]. Higher tick loads on R. fulvescens on treatment plots directly increase vector-host ratios, potentially resulting in increased tick-borne pathogen transmission [18].

The only known human pathogen we detected in ticks removed from mammals was R. parkeri, which was present in 1.4% of larvae and 6.7% of nymphs. Rickettsia parkeri is a spotted fever group Rickettsia long associated with A. maculatum and recently associated with human disease in the United States [19]. Although the apparent prevalence of R. parkeri infection in our study is low compared with recent research in Virginia (27–55% prevalence; [20]), these studies examined adult ticks located on the northern edge of the S. invicta invasion. It is unknown how the current pathogen community in rodent-associated ticks compared with that which occurred in the area prior to S. invicta invasion, and the spatial and temporal scale of the contemporary experimental suppression of S. invicta may not be sufficient to detect any alteration in pathogen infection associated with a reduction in ant numbers.

While S. invicta have pervasive impacts on the ecosystems they invade [16], including depressing populations of endangered taxa [12], land managers need to consider the incidental effects that S. invicta suppression may have on tick-borne disease dynamics in some systems. Our work implies that during its invasion S. invicta may have produced ecosystem cascading effects that could lead to decreased vector, host and pathogen abundance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank biologists at our field sites including Terry Rossignol, Rebecca Chester and Kirk Feuerbacher, and landowners for allowing property access. Numerous technicians assisted in the field and Lisa Auckland assisted in the laboratory. William Grant and three anonymous reviewers provided helpful comments on earlier versions of this manuscript.

Ethics

All procedures were approved by the Texas A&M Animal Care and Use Committee (permit no. 2012-100).

Data accessibility

Additional information is in the electronic supplementary material. Data are available from the Dryad Digital Repository: http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.6968k [21]. Tick and pathogen sequences are available on GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/; KX772750-KX772751 and KX772752-KX772759, respectively).

Authors' contributions

J.E.L., G.L.H., M.E.M., M.D.E., P.D.T. and S.A.H. conceived and designed the study. A.A.C. and M.E.M. collected field data. A.A.C. and M.C.I.M. performed the statistical analyses. All authors contributed to drafting the manuscript, approved the final version of the manuscript and agree to be held accountable for all aspects of the work.

Competing interests

We have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was supported by the Texas A&M Agrilife Invasive Ant Research and Management Project. Funding for S. invicta suppression was provided by the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

References

- 1.Allan BF, et al. 2010. Invasive honeysuckle eradication reduces tick-borne disease risk by altering host dynamics. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 18 523–18 527. ( 10.1073/pnas.1008362107) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swei A, Ostfeld RS, Lane RS, Briggs CJ. 2011. Effects of an invasive forest pathogen on abundance of ticks and their vertebrate hosts in a California Lyme disease focus. Oecologia 166, 91–100. ( 10.1007/s00442-010-1796-9) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Civitello DJ, Flory SL, Clay K. 2008. Exotic grass invasion reduces survival of Amblyomma americanum and Dermacentor variabilis ticks (Acari: Ixodidae). J. Med. Entomol. 45, 867–872. ( 10.1093/jmedent/45.5.867) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ostfeld RS, Keesing F. 2000. Biodiversity and disease risk: the case of lyme disease. Conserv. Biol. 14, 722–728. ( 10.1046/j.1523-1739.2000.99014.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Telfer S, Bown KJ, Sekules R, Begon I, Hayden T, Birtles R. 2005. Disruption of a host-parasite system following the introduction of an exotic host species. Parasitology 130, 661–668. ( 10.1017/A0031182005007250) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gust DA, Schmidly DJ. 1986. Small mammal populations on reclaimed strip-mined areas in Freestone County, Texas. J. Mammal. 67, 214–217. ( 10.2307/1381031) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Orrock JL, Danielson BJ. 2004. Rodents balancing a variety of risks: Invasive fire ants and indirect and direct indicators of predation risk. Oecologia 140, 662–667. ( 10.1007/s00442-004-1613-4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holtcamp WN, Williams CK, Grant WE. 2010. Do invasive fire ants affect habitat selection within a small mammal community? Int. J. Ecol. 2010, 1–7. ( 10.1155/2010/642412) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lechner KA, Ribble DO. 1996. Behavioral interactions between red imported fire ants (Solenopsis invicta) and three rodent species of south Texas. Southwest. Nat. 41, 123–128. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gleim ER, Conner LM, Yabsley MJ. 2013. The effects of Solenopsis invicta (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) and burned habitat on the survival of Amblyomma americanum (Acari: Ixodidae) and Amblyomma maculatum (Acari: Ixodidae). J. Med. Entomol. 50, 270–276. ( 10.1603/Me12168) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burns EC, Melancon DG. 1977. Effect of imported fire ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) invasion on Lone Star tick (Acarina: Ixodidae) populations. J. Med. Entomol. 14, 247–249. ( 10.1093/jmedent/14.2.247) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morrow ME, Chester RE, Lehnen SE, Drees BM, Toepfer JE. 2015. Indirect effects of red imported fire ants on Attwater's prairie-chicken brood survival. J. Wildl. Manage. 79, 898–906. ( 10.1002/jwmg.915) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allen CR, Epperson DM, Garmestani AS. 2004. Red imported fire ant impacts on wildlife: a decade of research. Am. Midl. Nat. 152, 88–103. ( 10.1674/0003-0031(2004)152[0088:Rifaio]2.0.Co;2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dobson ADM. 2014. History and complexity in tick-host dynamics: discrepancies between ‘real’ and ‘visible’ tick populations. Parasites Vectors 7, 231 ( 10.1186/1756-3305-7-231) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Randolph SE, Dobson ADM. 2012. Pangloss revisited: a critique of the dilution effect and the biodiversity-buffers-disease paradigm. Parasitology 139, 847–863. ( 10.1017/S00311820120002000) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oliver JH Jr, Lin T, Gao L, Clark KL, Banks CW, Durden LA, James AM, Chandler FW Jr. 2003. An enzootic transmission cycle of Lyme borreliosis spirochetes in the southeastern United States. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 11 642–11 645 ( 10.1073/pnas.1434553100) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Randolph SE. 2008. Dynamics of tick-borne disease systems: minor role of recent climate change. Rev. Sci. Tech. 27, 367–381. ( 10.20506/rst.27.2.1805) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woolhouse MEJ, et al. 1997. Heterogeneities in the transmission of infectious agents: implications for the design of control programs. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 94, 338–342. ( 10.1073/pnas.94.1.338) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paddock CD, Sumner JW, Comer JA, Zaki SR, Goldsmith CS, Goddard J, McLellan SLF, Tamminga CL, Ohl CA. 2004. Rickettsia parkeri: a newly recognized cause of spotted fever rickettsiosis in the United States. Clin. Infect. Dis. 38, 805–811. ( 10.1086/381894) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nadolny RM, Wright CL, Sonenshine DE, Hynes WL, Gaff HD. 2014. Ticks and spotted fever group rickettsiae of southeastern Virginia. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 5, 53–57. ( 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2013.09.001) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Castellanos AA, Medeiros MCI, Hamer GL, Morrow ME, Eubanks MD, Hamer SA, Light JE. 2016. Data from: Decreased small mammal and on-host tick abundance in association with invasive red imported fire ants (Solenopsis invicta). Dryad Digital Repository. ( 10.5061/dryad.6968k) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Additional information is in the electronic supplementary material. Data are available from the Dryad Digital Repository: http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.6968k [21]. Tick and pathogen sequences are available on GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/; KX772750-KX772751 and KX772752-KX772759, respectively).