Establishing the evolutionary origins of teeth is difficult not least since researchers disagree on whether or not the earliest jawed vertebrates, the extinct placoderms, possessed teeth. We recently showed that a gnathal plate from the acanthothoracid Romundina stellina comprises marginally added enameloid-capped tubercles. Burrow et al. [1] present concerns over the origin of our material, both taxonomic and topological, as well as the histological interpretation of the component tissues; none of their points are sustainable.

The skeletal plate that we interpreted as a gnathal of Romundina stellina (figure 1a–d) originated from the unsorted and unstudied personal collections of Tor Ørvig, derived from the same samples as the holotype [2]. Evidence of their attribution to Romundina is based on the shape and organization of tubercles, semidentine composition (placoderm-diagnostic tissue) and their co-association with Romundina, the only placoderm described from the locality. Unusually for placoderms, the dermal tubercles in R. stellina have enameloid caps [3], as do the morphologically distinct tubercles of the oral plate [4]. Support is found in another specimen previously attributed to Romundina [5] with a single rostral pair of gnathals, the structure of which has not been described. Its precise taxonomy is moot but irrelevant here since the articulated specimen is an acanthothoracid closely related to, if not, R. stellina.

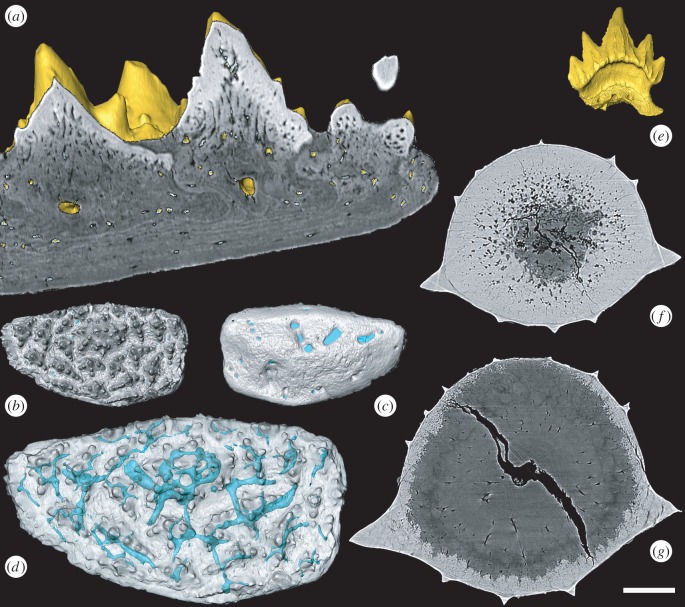

Figure 1.

Surface rendering and virtual thin-section of Romundina supragnathal (NRM-PZ P.15956, a–d) and Scyliorhinus canicula (BRSUG 29402) teeth (e–g). Romundina pulp cavities in transverse section (a) and vascular system in oral (b), dorsal (c) and oral transparent view (d). Scyliorhinus tooth (e) enameloid layer with radial structures (f,g). Scale bar represents 50 µm in (a), 417 µm in (b,c), 240 µm (d), 480 µm (e), 37 µm (f) and 45 µm (g).

The skeletal plate we described (figure 1a–d) is compatible with the articulated gnathal plates, comprised from approximately concentrically arranged rows of branched tubercles [4, fig. 1(a–d)]. Differences in overall outline and size reflect growth; the isolated oral plate is equivalent to the inner core of the articulated plate, lacking larger, later superimposed tubercles. We demonstrated that the oral plate grew by marginal addition of tubercles [4, fig. 1(a)], substantiating previous suggestions [5–7]. Burrow and colleagues contend that the gnathals of coeval arthrodires have concave cancellous gnathal bases and possess tubercles that increase in size through ontogeny, but we did not attempt to interpret the toothplate as belonging to an arthrodire. Acanthothoracids, like ptyctodontids, are distant relatives of arthrodires and the oral and aboral morphology of their gnathals are concomitantly distinct, reflecting differences in the surface they attach to [6]. In R. stellina, the supragnathal is associated with the flat surface of the ethmoid region, bordering the premedian plate anteriorly. In the premedian plate of an adult Romundina, perichondral and dermal bone are indistinguishable [8]. Both the articulated and isolated gnathals have central symmetrical tubercles surrounded by asymmetrically branched tubercles that are distinct from dermal tubercle morphologies (figure 1b) that typically possess radial ridges. The larger articulated plates [7], representing an older individual, have additional large, central superimposed denticles associated with the large marginal denticles, which represent a later growth stage than the one represented by the isolated supragnathal [4]. Further, the mode of plate growth in arthrodires is quite distinct from the oral elements of R. stellina which exhibit concentric marginal addition (figure 1a,b).

Burrow and colleagues [1] contend with our interpretation of the tissues comprising the gnathal plate of Romundina. Their arguments hinge on peculiar and readily falsifiable definitions of what constitutes a tooth and enameloid. A pulp cavity is neither necessary nor sufficient for the identification of teeth since chondrichthyan teeth often lack an open pulp (e.g. figure 1e–g) cavity that is present, nonetheless, in their dermal tubercles. Birefringence is a property of optical anisotropic materials; it does not define whether a material comprises crystallites. We drew comparison to the single crystallite enameloid that characterizes primitive chondrichthyan teeth and in which component crystallites are difficult to discern, even in living materials.

Ultimately, our thesis is eminently testable, by applying the same non-invasive methods that we employed, to the known articulated gnathal elements. We predict that they will exhibit the same composition, aboral morphology and mode of growth exhibited by the isolated gnathal plate that we have described. In the interim, the available evidence suggests that primitive gnathostome dentitions were capped with enameloid and lacked developmental independence from the dermal skeleton.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

The accompanying comment can be viewed at http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2016.0159.

Data accessibility

Data used in this manuscript are archived at http://dx.doi.org/10.5523/bris.37q0cntawxcq1rkktq3e9mr1p.

Authors' contributions

Authors contributed equally.

Competing interests

We have no competing interests.

Funding

This study is supported by NERC (NE/G016623/1) and NWO (VIDI 864.14.009).

References

- 1.Burrow C, Hu Y, Young G. 2016. Placoderms and the evolutionary origin of teeth: a comment on Rücklin & Donoghue (2015). Biol. Lett. 12, 20160159 ( 10.1098/rsbl.2016.0159) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ørvig T. 1975. Description, with special reference to the dermal skeleton, of a new radotinid arthrodire from the Gedinnian of Arctic Canada. In Problemes actuels de Paléontologie - Évolution des vertébrés. Colloque Int. CNRS 218, 41–71. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giles S, Rücklin M, Donoghue PCJ. 2013. Histology of ‘placoderm’ dermal skeletons: implications for the nature of the ancestral gnathostome. J. Morphol. 274, 627–644. ( 10.1002/jmor.20119) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rücklin M, Donoghue PCJ. 2015. Romundina and the evolutionary origin of teeth. Biol. Lett. 11, 20150326 ( 10.1098/rsbl.2015.0326) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith MM, Johanson Z. 2003. Response to comment on ‘Separate evolutionary origins of teeth from evidence in fossil jawed vertebrates’. Science 300, 1661 ( 10.1126/science.1084686) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johanson Z, Smith MM. 2005. Origin and evolution of gnathostome dentitions: a question of teeth and pharyngeal denticles in placoderms. Biol. Rev. 80, 303–345. ( 10.1017/S1464793104006682) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goujet D, Young GC. 2004. Placoderm anatomy and phylogeny: new insights. In Recent advances in the origin and early radiation of vertebrates (eds Arratia G, Wilson MVH, Cloutier R), pp. 109–126. München, Germany: Pfeil. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dupret V, Sanchez S, Goujet D, Tafforeau P, Ahlberg PE. 2010. Bone vascularization and growth in placoderms (Vertebrate): the example of the premedian plate of Romundina stellina Ørvig, 1975. C. R. Palevol. 9, 369–375. ( 10.1016/j.crpv.2010.07.005) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data used in this manuscript are archived at http://dx.doi.org/10.5523/bris.37q0cntawxcq1rkktq3e9mr1p.