Significance

Auxin is a key hormone regulating plant growth and development. We combine experiments and mathematical modeling to reveal how auxin levels are maintained via feedback regulation of genes encoding key metabolic enzymes. We describe how regulation of auxin oxidation via transcriptional control of Arabidopsis thaliana gene DIOXYGENASE FOR AUXIN OXIDATION 1 (AtDAO1) expression is important at low to normal auxin concentrations. In contrast, higher auxin levels lead to increased Gretchen Hagen3 expression and auxin conjugation. Integrating this understanding into a multicellular model of root auxin dynamics successfully predicts that the dao1-1 mutant has an auxin-dependent longer root hair phenotype. Our findings reveal the importance of auxin homeostasis to maintain this hormone at optimal levels for plant growth and development.

Keywords: hormone regulation, auxin, metabolism, homeostasis, Arabidopsis thaliana

Abstract

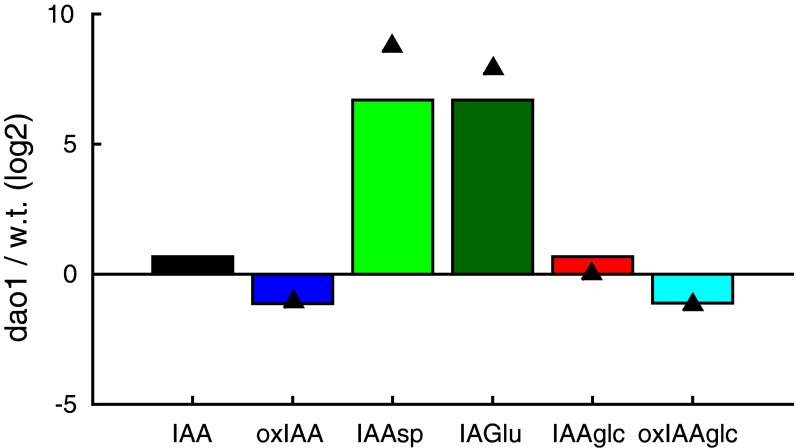

The hormone auxin is a key regulator of plant growth and development, and great progress has been made understanding auxin transport and signaling. Here, we show that auxin metabolism and homeostasis are also regulated in a complex manner. The principal auxin degradation pathways in Arabidopsis include oxidation by Arabidopsis thaliana gene DIOXYGENASE FOR AUXIN OXIDATION 1/2 (AtDAO1/2) and conjugation by Gretchen Hagen3s (GH3s). Metabolic profiling of dao1-1 root tissues revealed a 50% decrease in the oxidation product 2-oxoindole-3-acetic acid (oxIAA) and increases in the conjugated forms indole-3-acetic acid aspartic acid (IAA-Asp) and indole-3-acetic acid glutamic acid (IAA-Glu) of 438- and 240-fold, respectively, whereas auxin remains close to the WT. By fitting parameter values to a mathematical model of these metabolic pathways, we show that, in addition to reduced oxidation, both auxin biosynthesis and conjugation are increased in dao1-1. Transcripts of AtDAO1 and GH3 genes increase in response to auxin over different timescales and concentration ranges. Including this regulation of AtDAO1 and GH3 in an extended model reveals that auxin oxidation is more important for auxin homoeostasis at lower hormone concentrations, whereas auxin conjugation is most significant at high auxin levels. Finally, embedding our homeostasis model in a multicellular simulation to assess the spatial effect of the dao1-1 mutant shows that auxin increases in outer root tissues in agreement with the dao1-1 mutant root hair phenotype. We conclude that auxin homeostasis is dependent on AtDAO1, acting in concert with GH3, to maintain auxin at optimal levels for plant growth and development.

The plant hormone auxin regulates a myriad of processes in plant growth and development (1). Although significant progress has been made in understanding the molecular basis of auxin transport, perception, and response, the control of auxin metabolism and homeostasis via conjugation and degradation remains less well-studied.

Several forms of auxin conjugates have been identified in plants, including ester-linked indole-3-acetic acid (IAA)-sugar conjugates and amide-linked IAA-amino acid conjugates (2). In Arabidopsis thaliana, the Gretchen Hagen3 (GH3) family of auxin-inducible acyl amido synthetases has been shown to convert IAA to IAA-amino acids (3). Most amino acid IAA conjugates are believed to be inactive, and some, such as indole-3-acetic acid aspartic acid (IAA-Asp) and indole-3-acetic acid glutamic acid (IAA-Glu), can also be further metabolized (4–6). The conversion of IAA to indole-3-acetic acid glucose (IAA-glc) is catalyzed by the uridine diphosphate glucosyltransferase UGT84B1 (UGT) (7). The oxidized form of IAA, 2-oxindole-3-acetic acid (oxIAA), has been identified as a major IAA catabolite in Arabidopsis (4, 6, 8) and can be further metabolized by conjugation to glucose (9). oxIAA has been shown to be an irreversible IAA catabolite that has very little biological activity compared with IAA and is not transported via the polar auxin transport system (6, 8). Although these metabolites and pathways have been identified, it has been difficult to identify the genes and enzymes involved. Two closely related components of the IAA degradation machinery have recently been identified in Arabidopsis, DIOXYGENASE FOR AUXIN OXIDATION 1 (AtDAO1; At1g14130) and AtDAO2 (At1g14120) (10–12). AtDAO1 and AtDAO2 are closely related to genes described in apple [Adventitious Rooting Related Oxygenase 1 (13)] and rice [DAO (14)] and a family of gibberellin 2 (GA2) oxidases that mediates degradation of GAs (15). Radiolabeled IAA feeding studies of loss and gain of function AtDAO1 lines have shown that this oxidase represents the major regulator of auxin degradation to oxIAA in Arabidopsis (11). Metabolite profiling of mutant lines revealed that disrupting AtDAO1 regulation resulted in major changes in steady-state levels of oxIAA and IAA conjugates but not IAA. Hence, IAA conjugation and catabolism seem to regulate auxin levels in Arabidopsis in a highly redundant manner.

In this paper, we describe a systems biology approach to understanding the highly nonlinear regulation of auxin homeostasis in Arabidopsis. We initially use a mathematical model of auxin metabolism to reveal the importance in dao1-1 mutant plants of not only a reduction in IAA oxidation rate but a more than 200-fold increase in the rate of irreversible GH3 conjugation coupled with an increase in the rate of IAA biosynthesis. Our transcriptomic data show that there are feedbacks on the auxin degradation pathway, namely the IAA induction of AtDAO1 and members of the GH3 family. To investigate the effect of these feedbacks on auxin homeostasis, we add them to an extended model, revealing that the AtDAO1 degradation pathway is much more effective when IAA is at physiological levels, whereas the GH3 degradation pathway is dominant after high levels of IAA input. Finally, we embed our homeostasis model in a multicellular context that predicts that one spatial effect of the dao1-1 mutant is to increase IAA in outer root tissues, consistent with the auxin-dependent elongated root hair phenotype described for the dao1-1 mutant (11).

Results

A Mathematical Model of Auxin Metabolism Predicts That the dao1-1 Mutant Has Altered Rates of Auxin Oxidation, Conjugation, and Synthesis.

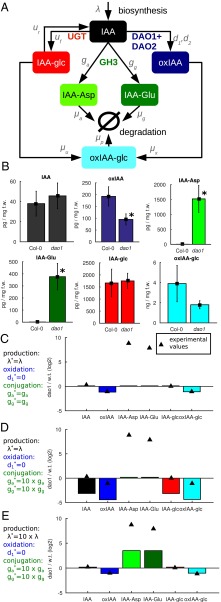

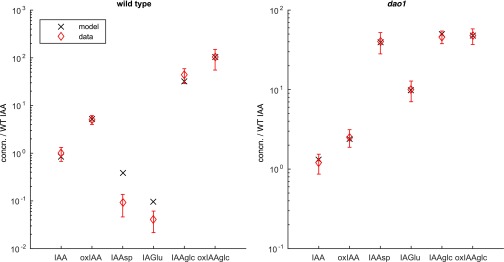

The principal degradation pathways in Arabidopsis include irreversible conjugation by GH3s and oxidation by AtDAO1/2 (Fig. 1A). In the roots of dao1-1 KO seedlings, oxidized IAA (oxIAA) levels are halved, and the conjugated forms IAA-Asp and IAA-Glu are increased by 438- and 240-fold, respectively, whereas the level of IAA is only increased by 20% (statistically insignificant) (Fig. 1B). These root data are consistent with metabolite profiling from whole seedlings and different tissues (11).

Fig. 1.

A metabolic model suggests that the dao1-1 mutant may have altered rates of metabolism other than IAA oxidation. (A) The principal degradation pathways in Arabidopsis include irreversible conjugation by GH3s and oxidation by DAO1/2. (B) In the dao1-1 KO, oxidized IAA (oxIAA) levels are halved and conjugated forms, IAA-Asp and IAA-Glu, are increased by more than 438- and 240-fold, respectively, whereas the level of IAA is increased by only 20%. *Statistically significant differences from Col-0 (P < 0.05; Student’s t test). (C and D) Mathematical modeling predicts that a decrease in oxidation rate alone is not sufficient to account for the increase in conjugation products and IAA homeostasis in dao1-1 and that increasing GH3 conjugation rates does not lead to a better qualitative match. (E) Increasing both IAA biosynthesis and GH3 conjugation rates in the dao1-1 simulation can qualitatively match metabolomic data. f.w., Fresh weight; oxIAA-glc, 2-oxoindole-3-acetic acid glucose; w.t., Col-0 WT.

To investigate whether the conceptual model of the main IAA degradation pathways summarized in Fig. 1A is consistent with the metabolite data given in Fig. 1B, a linear ordinary differential equation (ODE) model was formulated (Materials and Methods and SI Text). The model simulates the biosynthesis of IAA and its subsequent conversion to IAA-glc via UGT, IAA-Asp and IAA-Glu via GH3, and oxIAA via AtDAO1/2. IAA-glc and oxIAA can both be conjugated further to form 2-oxoindole-3-acetic acid glucose (oxIAA-glc), and oxIAA-glc and the conjugates IAA-Asp and IAA-Glu are then degraded at fixed rates. We calculated steady-state levels of the model variables in the WT (wild type), modeled the mutant by setting the rate of AtDAO1-mediated IAA oxidation in dao1-1 to zero (, where the * notation indicates a parameter value in the dao1-1 mutant), and estimated model parameters to best fit the data in Fig. 1B (see Table S1, set 1 for parameter values). The model is able to reproduce the observed reductions in and while maintaining levels of and but yields only an 8% increase in the levels of conjugated auxin (/), far less than the experimentally observed changes of greater than 200-fold (Fig. 1C and Fig. S1). Thus, our mathematical modeling predicts that a decrease in oxidation rate alone is not sufficient to account for the massive increase in conjugation products and IAA homeostasis in dao1-1.

Table S1.

Dynamic regulation of AtDAO1 and GH3 modulates auxin homeostasis

| Parameter | Set 1: dao1-1 only differs in rate of IAA oxidation | Set 2: dao1-1 differs in rates of IAA oxidation, biosynthesis, and conjugation | Set 3: dao1-1 only differs in rate of IAA oxidation, but AtDAO1 and GH3 are auxin-inducible |

| λ | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 1.36 | 1.36 | |

| 0.0155 | 0.5224 | — | |

| 0 | 0 | — | |

| 0.3324 | 0.0012 | — | |

| 0.3324 | 0.4382 | — | |

| 0.6399 | 0.0018 | — | |

| 0.6399 | 0.3594 | — | |

| 0.131 | 1.7864 | 515.7453 | |

| 0.0042 | 0.0428 | 13.5992 | |

| 1.4581 | 0.0123 | 0.0185 | |

| 3.0129 | 0.0407 | 0.0174 | |

| 0.0001 | 0.0006 | 0.0002 | |

| 0.0159 | 0.3856 | 0.3379 | |

| 0.0563 | 0.0012 | 0.0097 | |

| 0.0059 | 0.1860 | 0.1893 | |

| — | — | 1.8471 | |

| — | — | 0 | |

| — | — | 83.5023 | |

| — | — | 83.5023 | |

| — | — | 19.5837 | |

| — | — | 19.5837 | |

| — | — | 1 | |

| — | — | 1 | |

| — | — | 0.005 | |

| — | — | 9.0 | |

| — | — | 2.3227 | |

| — | — | 0.01 |

Representative fitted parameter sets for the various models for auxin homeostasis. Set 1: simple AtDAO1 KO model ( in dao1-1 simulation) using Eqs. S1a–S1f. Parameters with superscript * are for the dao1-1 case. Here, we assume , , and . Set 2: fitted parameter set using Eqs. S1a–S1f for dao1-1 simulation with , , and and free to vary within the default constraints. Set 3: Representative fitted parameter set for model with inducible AtDAO1 and GH3 used to produce Fig. 3 and as the basis for the parameterization of the multicellular model. Parameter constraints are in SI Text.

Fig. S1.

Best fit between simple dao1-1 KO model and metabolic data using Eqs. S1a–S1f and parameter values from Table S1, set 1.

To explore whether increased GH3 conjugation rates in dao1-1 can explain the data, we increased those rates 10-fold in our model, so that and . Using these parameters in the dao1-1 simulation surprisingly results in only a 13% increase in the level of and conjugates and decreases in all other metabolites (Fig. 1D). We conclude that altering GH3 conjugation rates is insufficient in isolation to explain the metabolic data. We, therefore, tested in our model whether increasing the auxin biosynthesis rate in dao1-1 () as well as GH3-mediated conjugation rates could capture the experimentally observed behavior of the dao1-1 mutant compared with the WT. Fig. 1E shows that increasing both IAA biosynthesis and GH3 conjugation rates in the dao1-1 simulation can qualitatively match metabolomic data. Hence, auxin homeostasis seems to be maintained in the IAA oxidase mutant dao1-1 by adjusting conjugation and synthesis rates.

Systems Analysis Reveals That, in Addition to Reduced Oxidation, both IAA Biosynthesis and Conjugation Are Increased in dao1-1.

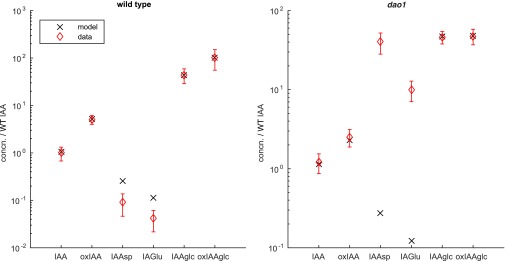

Next, we sought experimental evidence for changes in conjugation and synthesis rates before attempting more precise fitting of our model to the data. Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) shows that the mRNA expression level of GH3.3 is 2.7 times higher in dao1-1 than in the WT (Fig. 2A), and additional metabolite profiling in whole seedlings shows that the levels of three IAA precursors indole-3-acetamide (IAM), indole-3-pyruvic acid (IPyA), and indole-3-acetonitrile (IAN) all drop significantly in the dao1-1 mutant relative to the WT (Fig. 2B), indicating a higher IAA biosynthetic rate in dao1-1.

Fig. 2.

Experimental evidence and model optimization support the hypothesis that, in addition to reduced oxidation, both IAA biosynthesis and conjugation are increased in dao1-1. (A) Expression of the conjugating enzyme GH3.3 is elevated in dao1-1. (B) Levels of the IAA precursors IAM, IPyA, and IAN are all significantly reduced in dao1-1. *Statistically significant differences from Col-0 (P < 0.05; Student’s t test). (C) Box plot showing the first and third quartiles (bottoms and tops of blue boxes), medians (red lines), and lowest and highest data points within the interquartile range (black whiskers) plus outliers (red + symbols) of 100 fitted parameter sets. With IAA biosynthesis and conjugation rates free to vary in dao1-1, a wide range of parameter sets can fit the quantitative data. (D) Representative fit between model and data (dao1-1 relative to WT simulation). (E and F) Conjugation rates in dao1-1 ( and ) are predicted to be more than 200-fold larger than in WT ( and ) consistently across 100 parameter sets. f.w., Fresh weight; oxIAA-glc, 2-oxoindole-3-acetic acid glucose.

To further establish the plausibility of increased IAA biosynthesis and GH3 conjugation in the dao1-1 mutant, model parameters were fitted to the steady-state metabolite data for , , , , , and in both the WT and dao1-1. To fix the IAA synthesis rate in dao1-1 (), we assume that IAM, IPyA, and IAN have constant production rates (which do not vary between the WT and dao1-1) and that each is converted to IAA at a rate that is different in dao1-1 compared with in the WT. It follows that is inversely proportional to the corresponding drop in auxin precursor concentrations (0.74 averaged across IAM, IPyA, and IAN), giving . We then allowed the remaining parameters, including and (the respective rates, in the WT and dao1-1, of GH3-mediated conjugation to and ), to take any values within a wide range of fixed bounds. The parameter fitting used a hybrid genetic algorithm plus local minimum search, which sought to minimize the squared difference between model steady-state and metabolite data, for both the WT and dao1-1. We found that, with conjugation rates free to vary in dao1-1, a wide range of parameter sets can fit the quantitative data. (Fig. 2C). Running the parameter fitting algorithm a number of times, we generated 100 different parameter sets, which all result in good agreement of the model with data (well within the bounds of statistical experimental error). Plotting the distribution of each of the fitted parameter values shows that there is a limited degree of variability in some parameters between parameter sets (Fig. 2C). Fig. 2D and Fig. S2 show that the predicted relative changes between the WT and dao1-1 match those observed for six key metabolites (see Table S1, set 2 for parameter values). Fig. 2 E and F shows that the rates of conjugation via GH3 increase more than 400-fold (to IAA-Asp) and more than 200-fold (to IAA-Glu) in dao1-1 compared with in the WT, consistently across parameter sets.

Fig. S2.

Representative fit between dao1-1 simulation (with , , and and free to vary) and metabolic data using Eqs. S1a–S1f and parameter values from Table S1, set 2.

Dynamic Regulation of AtDAO1 and GH3 by Auxin Allows a Context-Dependent Homeostatic Response to Changes in Auxin.

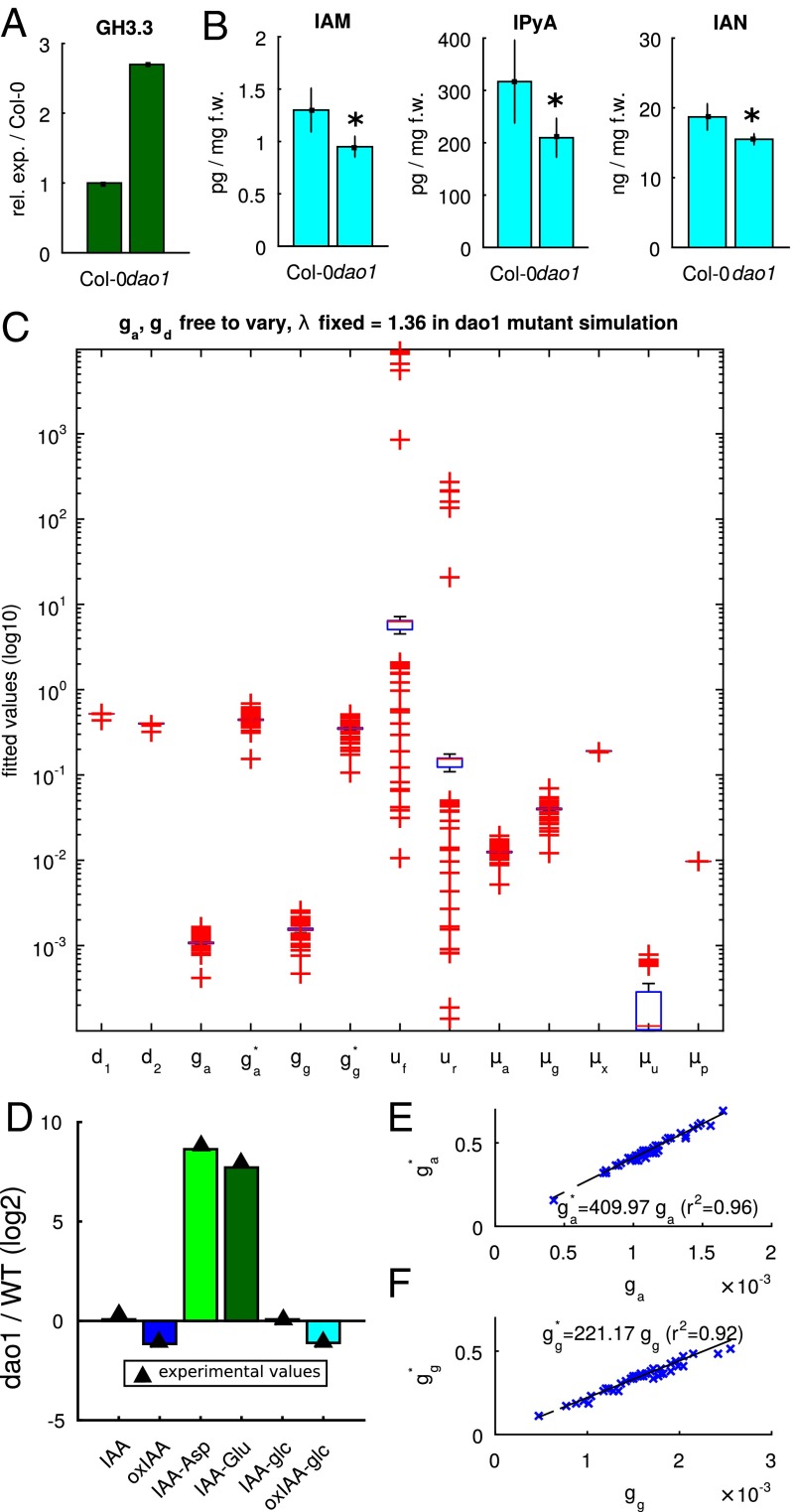

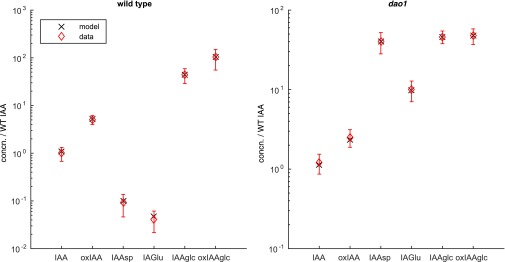

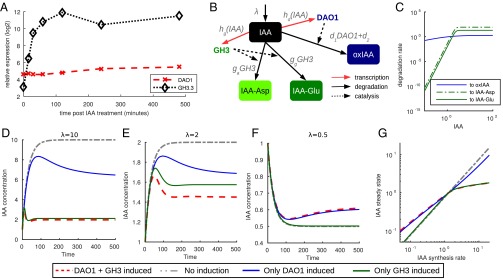

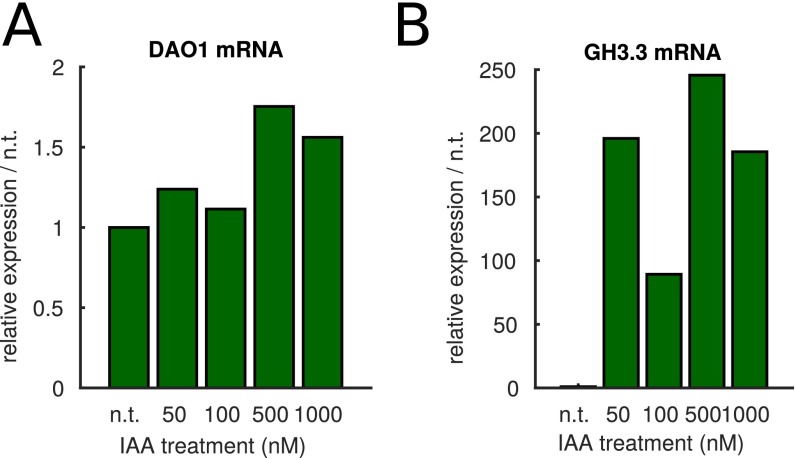

As expected for important components of the auxin homeostasis machinery, AtDAO1 and GH3 genes are auxin inducible (11, 16). Affymetrix-based transcriptomic analysis of auxin-treated root tips revealed that GH3.3 mRNA is induced very rapidly (peaking at 2 h), whereas AtDAO1 mRNA is induced more slowly (peaking at the final 4-h time point). qRT-PCR–based transcriptomic analysis also showed that GH3.3 is up-regulated 2.7-fold in dao1-1 (Fig. 2A) and around 200-fold in WT seedlings exposed to IAA (Fig. 3A and Fig. S3B). In contrast, IAA-treated WT seedlings show at most a 75% increase in AtDAO1 expression (Fig. 3A and Fig. S3A). We conclude that AtDAO1 and GH3.3 are up-regulated by auxin over different timescales and concentration ranges and with different fold changes in response.

Fig. 3.

AtDAO1 transcriptional regulation by IAA provides sensitivity at low auxin concentrations, whereas GH3 regulation contributes to homeostasis at high auxin concentrations. (A) Affymetrix data showing AtDAO1 and GH3.3 transcript abundance in microdissected root tips at time points after IAA treatment. (B–G) Mathematical modeling of these feedbacks on auxin degradation suggests that AtDAO1 is more effective in auxin homoeostasis at lower auxin concentrations, whereas GH3s contribute much more at high levels of auxin. (B) Submodel for IAA metabolism indicating the IAA-dependent transcription of AtDAO1 and GH3. (C) Effective AtDAO1- and GH3-dependent IAA degradation rates at steady state for fixed levels of IAA input. (D and E) Temporal response to 10- and 2-fold increases in IAA input with different combinations of modeled regulation. GH3 regulation is dominant. In each case, the model is shown with both AtDAO1 and GH3 inducible by auxin, only AtDAO1 inducible, and only GH3 inducible. (F) Temporal response to a twofold decrease in IAA input with different combinations of modeled regulation. AtDAO1 regulation is dominant. (G) The steady-state patterns seen in D–F are found across a wide range of IAA input rates.

Fig. S3.

qRT-PCR IAA dose–response data showing (A) AtDAO1 and (B) GH3.3 mRNA expression levels increasing with IAA; 7-d-old seedlings were treated with the stated IAA concentrations for 4 h. n.t., not treated.

To investigate the effect of these nonlinear feedbacks on auxin homeostasis, we incorporate them into an extended model (Fig. 3B), in which the expression of both AtDAO1 and GH3 increases as the concentration of IAA increases. To model these nonlinearities, we use Hill functions (Eqs. 2b and 2c), where the threshold parameters and determine the level of IAA at which gene expression reaches half-maximum, and the Hill coefficients and determine the sharpness of the transition from low to high expression. In the case of AtDAO1, we see at most a doubling of the mRNA level from basal expression under IAA treatment, with no sharp switch in expression observed (Fig. 3A and Fig. S3A), which suggests a half-maximum threshold similar to the basal IAA concentration. Hence, we fix and the Hill coefficient and fit the remaining model parameters to the steady-state metabolic WT and dao1-1 data. The fitted nonlinear model shows good agreement with the data (Figs. S4 and S5) and shows that a small increase in IAA biosynthesis rate (36%) can result in a much larger (>100-fold) increase in the level of IAA-Asp and IAA-Glu conjugates (see Table S1, set 3 for parameter values).

Fig. S4.

Representative fit between model with inducible AtDAO1 and GH3 and metabolic data, showing absolute concentrations of auxin and its metabolites using Eqs. S3a–S3e and parameter values from Table S1, set 3.

Fig. S5.

Representative fit between model with inducible AtDAO1 and GH3 and metabolic data, showing auxin and metabolite concentrations in dao1-1 relative to WT using Eqs. S3a–S3e and parameter values from Table S1, set 3.

Fig. 3C uses the estimated and fitted parameters to compare the contribution of the GH3 and AtDAO1 pathways with IAA degradation. Although the contribution of AtDAO1 increases slightly over the range shown and is still active even at low levels of IAA, conjugation rates are much lower at and below basal levels () but rapidly increase as IAA increases, so that for high levels of IAA (), the conjugation pathway is dominant.

Fig. 3 D–F shows the temporal response of the model after changing the input rate, λ, from the basal steady-state value (). To compare the relative importance of the AtDAO1 and GH3 degradation pathways as well as the “full” model with both up-regulated by IAA, we also show three alternate versions: one where only AtDAO1 is induced by auxin, one where only GH3 is induced by auxin, and one where neither response is induced. With the full model, there is a clearly homeostatic response with a transient peak, after which the steady-state level of IAA is much lower than the steady-state level without any AtDAO1/GH3 induction. For a large change in IAA input (Fig. 3D), this homeostasis is much more rapid and pronounced than for a relatively small change in IAA input (Fig. 3E). This difference in homeostatic responses is caused by variations in the magnitude and speed of AtDAO1 and GH3 responses to increased IAA as can be inferred from the simulations where the inducibility of one or the other is switched off. In the absence of GH3 induction, homeostasis is greatly reduced for a 10-fold increase in IAA input (Fig. 3D), whereas for a 2-fold reduction, the homeostatic response is largely unchanged from the full model (Fig. 3F). Conversely, in the absence of AtDAO1 regulation, the homeostatic effect is only slightly reduced for a 10-fold IAA increase, whereas it is undetectable for a 2-fold reduction in IAA input. For a twofold increase in IAA input, both the AtDAO1 and GH3 pathways contribute to IAA homeostasis (Fig. 3E).

Mathematical modeling of these feedbacks on auxin degradation suggests that AtDAO1 is more effective for auxin homeostasis at lower auxin concentrations, whereas GH3s are much more important at high auxin levels. The difference between the GH3 and AtDAO1 degradation pathways is illustrated further in Fig. 3G, which shows the IAA steady state for a range of values of the auxin input rate λ for each of the model variants described above. Here, corresponds to typical physiological levels. Around this level and below, the AtDAO1 degradation pathway is more active, but above this level, the GH3 pathway becomes more active and eventually, is much more important than AtDAO1 in removing large quantities of excess IAA.

Multicellular Root Modeling Predicts Auxin Accumulation in Epidermal Tissues.

We developed a spatial model for auxin transport and metabolism, combining our compartmental ODE model for IAA metabolism and IAA-dependent induction of AtDAO1 and GH3 (described above) with the multicellular model for IAA transport described in ref. 17. The multicellular model is based on actual root cell geometries and auxin influx and efflux carrier subcellular localizations. The IAA concentration is defined in each cell together with terms for the rates of carrier-dependent transport between cells.

Following ref. 17, we prescribed PIN, AUX, and LAX auxin efflux and influx carrier distributions in our virtual root tissues, with the PIN carriers polarized according to reports in the literature and our own observations using anti-PIN antibodies. The model also incorporated a weak background efflux to account for low levels of nonpolar PIN and the presence of other transporters, such as ABCB. We specified small auxin production rates within every cell and higher auxin production in the quiescent centre and columella initials. The model also captured auxin diffusion through the apoplast, as measured in ref. 18. We treated auxin concentrations as uniform within each cell because of the small size of cells in this region and relatively rapid auxin diffusion within the cytoplasm compared with within the apoplast (18–20). The small cells near the root tip are in contrast with the larger cells farther from the root tip, where subcellular variations in auxin have previously been considered (21, 22).

The resulting model can be described by a system of ODEs for the auxin concentrations within each cell and each segment of apoplast. Details and model parameter values are in SI Text and ref. 17. As done previously, we included a flux of auxin from the shoot by prescribing a nonzero auxin concentration within the stele cells at the boundary of the modeled tissue. In the epidermal, cortical, and endodermal cells, we assume that the auxin concentrations have reached their far-field asymptotic values, hence setting them equal to those in neighboring (rootward) cells of the same type. This assumption implies an appropriate shootward flux of auxin through the outer tissue layers (19). Starting from an initial condition in which all remaining concentrations equal zero, we simulated the ODEs until the concentrations and fluxes reached a steady state.

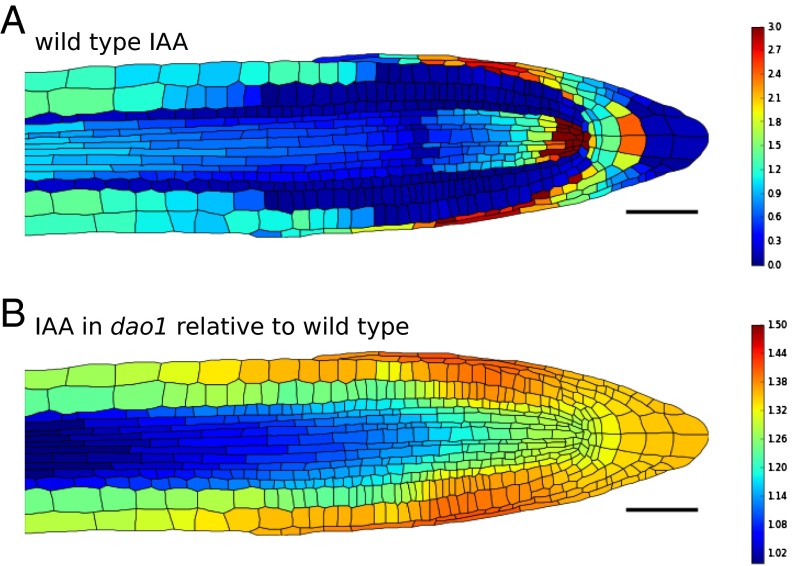

Embedding our homeostasis model into a multicellular context allows us to predict the effect of the dao1-1 mutant on IAA levels and distribution in root tissues compared with the WT. Simulations using our combined transport and homeostasis model predict that the WT IAA distribution (Fig. 4A) is in good agreement with spatial patterns inferred from the DII-VENUS fluorescent auxin signaling sensor (17). Although the spatial pattern in the dao1-1 mutant is similar to the WT, the total concentration of IAA was predicted to increase by 26%, consistent with the metabolite data (Fig. 1B). Very interestingly, the simulated increase in auxin is predicted to be spatially inhomogeneous, with auxin concentrations in outer root tissues increased >40% (Fig. 4B). The predicted increase in IAA in the dao1-1 mutant outer root tissues is consistent with the observed extraelongated root hair phenotype, which is known to be auxin dependent (23).

Fig. 4.

Multicellular simulation showing auxin accumulation in outer tissues of the root apex in dao1-1 relative to the WT. (A) Predicted IAA in the WT simulation relative to the fixed reference value of IAA = 1 in the stele at the shootward end of the tissue as defined in the boundary conditions. (B) In dao1-1, auxin is up to 40% higher in the epidermis, which is consistent with increased RSL4 expression, causing the increased root hair phenotype seen in the dao1-1 mutant (11). (Scale bar: 50 μm.)

Discussion

Our systems-based study has revealed that auxin homeostasis is controlled by highly redundant regulatory mechanisms involving auxin oxidation, conjugation, and synthesis pathways. These auxin homeostasis regulatory mechanisms are also highly nonlinear, involving multiple feedback loops that control the expression of AtDAO1 IAA oxidase and GH3 IAA conjugation enzymes. These regulatory mechanisms also operate across a range of spatial and temporal scales and auxin concentrations. For example, AtDAO1 and GH3 exhibit contrasting slow and rapid temporal expression dynamics, respectively. These differences in timing of AtDAO1 and GH3 induction by auxin are likely to be functionally very important. The slow auxin induction of AtDAO1 ensures that perturbations in this signal can still cause a desired developmental response, while helping the cell maintain an optimal level of auxin. GH3, however, is only induced when auxin is high and therefore, may be expressed rapidly to remove excess auxin as quickly as possible. The triggering of the GH3 degradation pathway at high levels of auxin is possibly a stress response to excess auxin levels and likely in effect during many laboratory experiments when large amounts of exogenous auxin are applied. However, Kramer and Ackelsberg (24) recently suggested that the GH3 conjugation pathway may be important at sites of high auxin accumulation during normal growth, such as lateral root primordia or within the shoot apical meristem.

Despite these myriad auxin homeostasis mechanisms operating in plants, our multicellular model predicted that disrupting just the IAA oxidase AtDAO1 is still able to perturb auxin levels in selected root tissues. These changes in auxin levels included elevated concentration in the dao1-1 mutant epidermis (Fig. 4B), the tissue from which root hairs originate and elongate in an auxin-dependent manner.

Datta et al. (25) have recently shown that root hair length is directly proportional to the abundance of a basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor RSL4, which has expression that is auxin inducible. Hence, we would predict (based on our multicellular model simulations) that RSL4 and root hair length would increase in proportion to the >40% increase in auxin levels in the dao1-1 mutant epidermis. Consistent with our model predictions, Porco et al. (11) report similar increases in RSL4 mRNA abundance and root hair length in the dao1-1 mutant epidermis experimentally. Hence, we reason that auxin levels may also be perturbed in other dao1-1 mutant tissues and/or stages of development, helping to explain why, despite the highly redundant organization of auxin homeostasis, dao1-1 exhibits a number of subtle auxin-related mutant phenotypes in root, shoot, and floral tissues (11, 12).

Materials and Methods

Plant Material and Growth Conditions.

A. thaliana Columbia-0 (Col-0) was used as the WT in all experiments. All transfer DNA insertion mutants were obtained from the Nottingham Arabidopsis Stock Centre. WT and mutant plants were grown as described in ref. 11.

RNA Isolation and Analysis.

Sterilized seeds were plated on one-half Murashige and Skoog media, stratified at 4 °C for 24 h to synchronize germination, and then transferred to a controlled growth chamber; 7-d-old seedlings on plates were then transferred to Murashige and Skoog media containing 1 μM IAA for varying lengths of time. RNA was extracted from root tips and used for microarray analysis with the Affymetrix ATH1 array.

IAA Metabolite Profiling.

A. thaliana WT Col-0 and the dao1-1 mutant were grown under long-day conditions for 7 or 10 d. Whole seedlings or dissected tissues were collected in five replicates (20 mg tissue per sample). Sample purification and quantification of IAA metabolites were performed as described in ref. 26.

Mathematical Models and Parameter Estimation.

Here, we summarize our mathematical models of the auxin homeostasis network. Full details of all models, definitions of model variables and parameters, and parameter estimation are in SI Text.

IAA Metabolism Model.

The simplest model of the pathway shown in Fig. 1A has a constant rate of IAA biosynthesis (λ) and linear rates of degradation and conversion from one form of auxin to another:

| [1a] |

| [1b] |

| [1c] |

| [1d] |

| [1e] |

and

| [1f] |

Inducible AtDAO1-GH3 Model.

We extend Eqs. 1a–1f by assuming that the rate of conversion of IAA to oxIAA () is proportional to the level of a new variable representing AtDAO1 and that the rates of conjugation of IAA to IAA-Asp () and IAA-Glu () are proportional to the level of another new variable representing GH3s. and are assumed to be produced in response to , represented by Hill functions, and decay linearly, so that

| [2a] |

| [2b] |

and

| [2c] |

Multicellular Model.

The multicellular model is described in SI Text.

SI Text

1. Linear ODE Model of IAA Degradation.

To investigate whether the conceptual model of the main IAA degradation pathways summarized in Fig. 1A is consistent with the metabolite data given in Fig. 1B, a simple linear ODE model was formulated as described below in SI Text, 1.1. Model reactions and SI Text, 1.2. Model equations. The model simulates the biosynthesis of IAA and its subsequent conversion to IAA-glc via UGT, IAA-Asp and IAA-Glu via GH3, and oxIAA via AtDAO1/2. IAA-glc and oxIAA can both be conjugated further to form 2-oxoindole-3-acetic acid glucose (oxIAA-glc), and oxIAA-glc and the conjugates IAA-Asp and IAA-Glu are then degraded at fixed rates (to prevent accumulation of these products in the model system).

1.1. Model reactions.

In the following, the empty set notation is used to denote a fixed pool of molecules from and into which model variables can be synthesized and degraded, respectively. We assume that all substrates, such as the amino acids Asp and Glu, are available in excess, so that this pool is neither depleted nor increased. A review of the IAA metabolic pathways modeled here is in ref. 27.

We initially consider the input of IAA to the system to be at some fixed rate λ:

This IAA synthesis step is considered in more detail, taking into account quantitative IAA precursor data, in SI Text, 2. IAA Precursors.

The oxidative pathway is modeled by the conversion of IAA to oxIAA by the combined action of AtDAO1 and AtDAO2 with respective rate constants and , the subsequent conversion of oxIAA to oxIAA-glc with rate , and finally, the degradation of oxIAA-glc with rate :

GH3-mediated conjugation is modeled by two pathways: one that models the conjugation of IAA with aspartic acid with rate to produce IAA-Asp and another that models the conjugation of IAA with glutamate with rate to produce IAA-Glu:

where and are the respective degradation rates of IAA-Asp and IAA-Glu.

Finally, the conversion of IAA to IAA-glc via UGT is modeled with rate constant , with the reverse reaction also included with rate . IAA-glc can also be converted to oxIAA-glc with rate , which as previously stated, degrades with rate :

1.2. Model equations.

Using the law of mass action, we cast the set of the reactions described in SI Text, 1.1. Model reactions as a set of ODEs for six variables:

| [S1a] |

| [S1b] |

| [S1c] |

| [S1d] |

| [S1e] |

and

| [S1f] |

Time is dimensionless, scaled by the dimensional biosynthesis rate (), and divided by the IAA concentration in the WT (), so that for the WT, . All other model species are nondimensionalized by scaling with .

1.3. dao1-1 Mutant simulations.

We use the * superscript notation to indicate the mutant value when parameter values may differ from their WT values in the dao1-1 simulations. For example, the WT rate of AtDAO1-mediated oxidation is denoted , whereas the value in the dao1-1 mutant is denoted .

The simplest way to model the dao1-1 KO mutant is to set in Eqs. S1a–S1f. However, if setting is the only difference between WT and mutant simulations, it is not possible to get good agreement between the model steady states and the metabolic data (Fig. 1C and Fig. S1) when running the parameter fitting algorithm (SI Text, 3. Parameter Fitting). The best fit parameter set is given in Table S1, set 1 and used as the base parameter set for additional modifications of parameter values in the dao1-1 simulations (Fig. 1 D and E).

Based on this fitting of the initial model and with support from additional experimental data (Fig. 2 A and B) in subsequent parameter fitting exercises, we may also allow the IAA synthesis rate () and the conjugation rates ( and ) to vary from their WT values in the dao1-1 mutant simulations. Fig. 1D uses the parameters in Table S1, set 1, except and , whereas in Fig. 1E, , , and .

2. IAA Precursors.

To fix the IAA synthesis rate in dao1-1 (), we assume that IAA precursors have constant production rates (which do not vary between the WT and dao1-1) and that each precursor is converted to IAA at a rate that is different in dao1-1 compared with the WT.

If we denote the pool of IAA precursors in the WT and in dao1-1 and assume that they are governed by the following:

and

where δ is the constant synthesis rate, and λ and are the respective conversion rates to . Then, at steady state, we can rearrange to obtain

It follows that is inversely proportional to the corresponding drop in auxin precursor concentrations (0.74 averaged across IAM, IPyA, and IAN from the whole-seedling metabolite data shown in Fig. 1), giving (because ).

3. Parameter Fitting.

During the parameter fitting and all other single-compartment simulations, the systems of ODEs were solved from zero initial conditions in Matlab using the function ode15s. To simulate WT plants, the models were run with one parameter set to steady state, and the same model was run with another parameter set to represent the dao1-1 mutant. The steady-state values were then compared with the data.

For the parameter estimation problems described below, we used the genetic algorithm (function ga) followed by local minimum search (function fmincon) from the Matlab Optimization toolbox to minimize the error between the data and model simulations. The objective function to be minimized was

| [S2] |

where M represents model steady-state values, and D represents data points with associated error σ. The superscript denotes the WT (Col-0), whereas denotes the -1 KO model variant and mutant plants. X is the set of metabolites , , , , , and , the data for which are normalized relative to the WT IAA measurement, consistent with the nondimensional models. Unless stated, all parameters were identical in the WT and dao1-1 simulations, save the mutant value for the AtDAO1 oxidation rate , and constrained between and . In all cases, the WT IAA production rate (λ) was fixed at .

The results of the parameter fitting in the simplest case, where only differs from the WT in the dao1-1 simulation, are shown in Fig. 1 and Fig. S1, and the parameters are given in Table S1, set 1.

In Fig. 2, the linear model (Eqs. S1a–S1f) was fitted against the data, with and free to vary within the default constraints, whereas was fixed at (SI Text, 2. IAA Precursors). The representative parameter set used to produce Fig. 2D and Fig. S2 is given in Table S1, set 2.

4. Inducible AtDAO/GH3 Model.

4.1. Model formulation.

The model is as the initial model (Eqs. S1a–S1f), except that the rate of conversion of IAA to oxIAA is proportional to the level of a new variable representing the level of AtDAO1, and the rates of conjugation of IAA to IAA-Asp and IAA-Glu are proportional to the level of another new variable representing the level of GH3, so that

| [S3a] |

| [S3b] |

and

| [S3c] |

where , , and are new parameters.

and are themselves produced at rates nonlinearly dependent on the level of represented by Hill functions, so that

| [S3d] |

and

| [S3e] |

4.2. Parameter fitting.

The inducible model was also fitted to the same metabolic data using the same algorithm as the linear model (SI Text, 3. Parameter Fitting). The only parameter that differed from the WT in dao1-1 was , which was again fixed at ; and were found using the parameter fitting but constrained and . This upper bound on was selected to ensure that the response of GH3 occurs within approximate physiological bounds of the level of IAA. The parameters , , , and do not directly affect the fit with the metabolic data, and they were instead separately estimated based on the available GH3 and AtDAO1 mRNA expression data and fixed during the parameter fitting algorithm. We fit the remaining model parameters to the steady-state metabolic WT and dao1-1 data. Because we see, at most, a doubling of the mRNA level from basal expression under IAA treatment, with no sharp switch in expression observed (Fig. S3A), we fix both the Hill coefficient () and the binding threshold () ; and affect the respective timescales over which AtDAO1 and GH3 can change. We estimate that gene expression will evolve over a slower timescale than biosynthesis, with AtDAO1 changing more slowly than GH3, and therefore, we set and .

The representative fitted parameter set used to produce Fig. 3 C–G and Figs. S4 and S5 is given in Table S1, set 3 and used as the basis for parameterization of the multicellular model.

4.3. Model variants.

For each of the model variants described below, the model was run to steady state (using the parameters in Table S1, set 3) with ; then, using these results as the initial conditions for a new set of simulations for , the time courses shown in Fig. 3 D–F were plotted. The steady state of each model variant is also plotted for in Fig. 3G.

4.3.1. Only AtDAO1 induced.

The induction of GH3 is switched off by setting

with the initial condition that is equal to its steady-state value in Eq. S3e when , i.e.,

4.3.2. Only GH3 induced.

Similarly, we switch off the induction of AtDAO1 by setting

4.3.3. No induction.

Both inducible pathways are switched off by setting

5. Multicellular Model.

The multicellular model is based on that in ref. 17, in which auxin transport is embedded in a realistic root cell geometry, using a vertex-based data structure from the OpenAlea modeling framework (28), with experimentally observed locations for the PIN, AUX, and LAX auxin efflux and influx carriers. To incorporate the AtDAO1/GH3 homeostasis model, we replace the linear production and degradation of IAA in ref. 17 with the production and nonlinear degradation defined in Eqs. S1a and S3a–S3c, so that, in general terms, for every cell i,

| [S4] |

where (as in ref. 17) is a constant of proportionality to ensure that the relative contribution of metabolism and transport remains similar in the two models. All remaining model variables are simulated in every cell as in the inducible model.

The metabolism terms are identical to the right-hand side of Eq. S1a, with the IAA-inducible versions of , , and as defined in Eqs. S3a–S3e. Parameter values are as estimated by the fitting algorithm as defined in Table S1, set 3, with two exceptions. To maximize the number of cells in which the IAA homeostasis model works at basal levels of IAA in the same way as described in the single-compartment models (i.e., relatively low GH3 conjugation and intermediate levels of AtDAO1 oxidation), we set the thresholds in the Hill functions for and higher, so that and ; (WT) and (dao1-1 mutant) in all cells except in the quiescent center and columella initials, where and , again reflecting the cell type-specific differences modeled in ref. 17.

The transport terms, parameter values, initial conditions, and efflux/influx carrier positions are identical to those defined in ref. 17. In summary, movement of IAA (denoted in ref. 17) is simulated between every cell and its neighboring apoplastic compartments and between every apoplastic compartment and neighboring apoplastic compartments (via quasisteady-state concentrations of IAA at the vertices between apoplastic compartments) using the following model:

| [S5a] |

and

| [S5b] |

where and denote the IAA concentration and area of cell i, respectively, and and are the IAA concentration and segment length of the apoplastic compartment between cells i and j, respectively.

is the set of neighboring cells to cell i, is the number of apoplastic compartments between cells i and j, and is the pair of vertices adjacent to apoplastic compartment ; δ is a parameter defining the apoplast width.

Finally, is the flux from apoplast compartment into cell i, and is the flux into apoplastic compartment from one of two neighboring vertices . Both and are defined as in ref. 17.

For the boundary conditions, as done previously, we included a flux of auxin from the shoot by prescribing a nonzero auxin concentration within the stele cells at the shootward boundary of the modeled tissue (17). In the epidermal, cortical, and endodermal cells, we assume that the auxin concentrations have reached their far-field asymptotic values, hence setting them equal to those in neighboring (rootward) cells of the same type. This boundary condition is slightly different from that in ref. 17, which sets the boundary cells to have zero auxin concentration, and implies an appropriate shootward flux of auxin through the outer tissue layers (19)—moreover, we have checked that this modification makes no significant difference to the model predictions.

Acknowledgments

N.M., L.R.B., T.H., M.H.W., U.V., J.R.K., M.J.B., and M.R.O. acknowledge support from the Biological and Biotechnology Science Research Council Responsive Mode Awards to the Centre for Plant Integrative Biology. N.M., M.J.B., and M.R.O. acknowledge European Research Council Futureroots funding. L.R.B. acknowledges funding from the Leverhulme Trust. A.R. and M.J.B. also acknowledge support from the Saudi Arabian Ministry of Higher Education.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

See Commentary on page 10742.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1604458113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Vanneste S, Friml J. Auxin: A trigger for change in plant development. Cell. 2009;136(6):1005–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ludwig-Müller J. Auxin conjugates: Their role for plant development and in the evolution of land plants. J Exp Bot. 2011;62(6):1757–1773. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Staswick PE, et al. Characterization of an Arabidopsis enzyme family that conjugates amino acids to indole-3-acetic acid. Plant Cell. 2005;17(2):616–627. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.026690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Östin A, Kowalyczk M, Bhalerao RP, Sandberg G. Metabolism of indole-3-acetic acid in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 1998;118(1):285–296. doi: 10.1104/pp.118.1.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kai K, Horita J, Wakasa K, Miyagawa H. Three oxidative metabolites of indole-3-acetic acid from Arabidopsis thaliana. Phytochemistry. 2007;68(12):1651–1663. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pencík A, et al. Regulation of auxin homeostasis and gradients in Arabidopsis roots through the formation of the indole-3-acetic acid catabolite 2-oxindole-3-acetic acid. Plant Cell. 2013;25(10):3858–3870. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.114421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jackson RG, et al. Identification and biochemical characterization of an Arabidopsis indole-3-acetic acid glucosyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(6):4350–4356. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006185200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peer WA, Cheng Y, Murphy AS. Evidence of oxidative attenuation of auxin signalling. J Exp Bot. 2013;64(9):2629–2639. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanaka K, et al. UGT74D1 catalyzes the glucosylation of 2-oxindole-3-acetic acid in the auxin metabolic pathway in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2014;55(1):218–228. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pct173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Voß U, et al. The circadian clock rephases during lateral root organ initiation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7641. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Porco S, et al. Dioxygenase-encoding AtDAO1 gene controls IAA oxidation and homeostasis in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:11016–11021. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1604375113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang J, et al. DAO1 catalyzes temporal and tissue-specific oxidative inactivation of auxin in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:11010–11015. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1604769113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Butler ED, Gallagher TF. Characterization of auxin-induced ARRO-1 expression in the primary root of Malus domestica. J Exp Bot. 2000;51(351):1765–1766. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/51.351.1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao Z, et al. A role for a dioxygenase in auxin metabolism and reproductive development in rice. Dev Cell. 2013;27(1):113–122. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas SG, Phillips AL, Hedden P. Molecular cloning and functional expression of gibberellin 2- oxidases, multifunctional enzymes involved in gibberellin deactivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(8):4698–4703. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park JE, et al. GH3-mediated auxin homeostasis links growth regulation with stress adaptation response in Arabidopsis. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(13):10036–10046. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610524200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Band LR, et al. Systems analysis of auxin transport in the Arabidopsis root apex. Plant Cell. 2014;26(3):862–875. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.119495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kramer EM, Frazer NL, Baskin TI. Measurement of diffusion within the cell wall in living roots of Arabidopsis thaliana. J Exp Bot. 2007;58(11):3005–3015. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Band LR, King JR. Multiscale modelling of auxin transport in the plant-root elongation zone. J Math Biol. 2012;65(4):743–785. doi: 10.1007/s00285-011-0472-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swarup R, et al. Root gravitropism requires lateral root cap and epidermal cells for transport and response to a mobile auxin signal. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7(11):1057–1065. doi: 10.1038/ncb1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laskowski M, et al. Root system architecture from coupling cell shape to auxin transport. PLoS Biol. 2008;6(12):e307. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Payne RJH, Grierson CS. A theoretical model for ROP localisation by auxin in Arabidopsis root hair cells. PLoS One. 2009;4(12):e8337. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pitts RJ, Cernac A, Estelle M. Auxin and ethylene promote root hair elongation in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 1998;16(5):553–560. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kramer EM, Ackelsberg EM. Auxin metabolism rates and implications for plant development. Front Plant Sci. 2015;6:150. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Datta S, Prescott H, Dolan L. Intensity of a pulse of RSL4 transcription factor synthesis determines Arabidopsis root hair cell size. Nat Plants. 2015;1:15138. doi: 10.1038/nplants.2015.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Novák O, et al. Tissue-specific profiling of the Arabidopsis thaliana auxin metabolome. Plant J. 2012;72(3):523–536. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.05085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ljung K. Auxin metabolism and homeostasis during plant development. Development. 2013;140(5):943–950. doi: 10.1242/dev.086363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pradal C, Dufour-Kowalski S, Boudon F, Fournier C, Godin C. OpenAlea: A visual programming and component-based software platform for plant modelling. Funct Plant Biol. 2008;35(10):751–760. doi: 10.1071/FP08084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]