Significance

Adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the fuel of life, is produced by a molecular machine consisting of two motors linked by a rotor. One generates rotation by consuming energy derived from oxidative metabolism or photosynthesis; the other uses energy transmitted by the rotor to put ATP molecules together from their building blocks adenosine diphosphate and phosphate. In many species the machine is easily reversible, and various different mechanisms to regulate the reverse action have evolved so that it is used only when needed. In some eubacterial species, including the thermoalkaliphile Caldalkalibacillus thermarum, although evidently constructed in a similar way to reversible machines, the reverse action is severely impeded, evidently because the products of hydrolysis remain bound to the machine.

Keywords: Caldalkalibacillus thermarum, F1-ATPase, structure, inhibition, regulation

Abstract

The crystal structure has been determined of the F1-catalytic domain of the F-ATPase from Caldalkalibacillus thermarum, which hydrolyzes adenosine triphosphate (ATP) poorly. It is very similar to those of active mitochondrial and bacterial F1-ATPases. In the F-ATPase from Geobacillus stearothermophilus, conformational changes in the ε-subunit are influenced by intracellular ATP concentration and membrane potential. When ATP is plentiful, the ε-subunit assumes a “down” state, with an ATP molecule bound to its two C-terminal α-helices; when ATP is scarce, the α-helices are proposed to inhibit ATP hydrolysis by assuming an “up” state, where the α-helices, devoid of ATP, enter the α3β3-catalytic region. However, in the Escherichia coli enzyme, there is no evidence that such ATP binding to the ε-subunit is mechanistically important for modulating the enzyme’s hydrolytic activity. In the structure of the F1-ATPase from C. thermarum, ATP and a magnesium ion are bound to the α-helices in the down state. In a form with a mutated ε-subunit unable to bind ATP, the enzyme remains inactive and the ε-subunit is down. Therefore, neither the γ-subunit nor the regulatory ATP bound to the ε-subunit is involved in the inhibitory mechanism of this particular enzyme. The structure of the α3β3-catalytic domain is likewise closely similar to those of active F1-ATPases. However, although the βE-catalytic site is in the usual “open” conformation, it is occupied by the unique combination of an ADP molecule with no magnesium ion and a phosphate ion. These bound hydrolytic products are likely to be the basis of inhibition of ATP hydrolysis.

The F-ATPases (F1Fo-ATP synthases) from chloroplasts, mitochondria, and eubacteria have evolved different ways of regulating ATP hydrolysis (1). During darkness, chloroplast F-ATPases use a redox inhibitory mechanism (2, 3). Mitochondrial enzymes bind an inhibitor protein called IF1, inhibitor of F1-ATPase (4–7), and α-proteobacterial F-ATPases have a related inhibitor protein called the ζ-subunit (8–10). Many eubacterial F-ATPases synthesize ATP in the presence of oxygen and, under anaerobic conditions, hydrolyze ATP made by substrate-level phosphorylation to generate the proton-motive force, which is required for maintaining cell viability in the absence of growth. When the proton-motive force and cellular ATP concentration are low, an inhibitory mechanism that may operate to prevent ATP wastage has been demonstrated in vitro for the F-ATPases from Escherichia coli (11), Geobacillus stearothermophilus (12), and Thermosynechococcus elongatus (13) involving their ε-subunit. This subunit, a component of the rotor of the enzyme, is folded into an N-terminal nine-stranded β-sandwich and a C-terminal α-helical hairpin (13–18). The β-sandwich binds the subunit to the γ-subunit and to the c ring in the membrane domain, and the α-helices adopt two conformations, “down” and “up.” In the down state of the F-ATPase from G. stearothermophilus, the α-helices of the ε-subunit bind an ATP molecule and are associated with the β-sandwich (17); in the absence of bound ATP, the α-helices assume the up position, interacting with the α3β3-domain and inhibiting ATP hydrolysis (18). Up positions have been captured in structures of the F1-domains from E. coli (19, 20), but the isolated ε-subunit remains in a down conformation even when ATP is not bound to it (14–16). Deletion of its five C-terminal amino acids diminished respiratory growth (21), but deletion of the C-terminal domain had no growth phenotype (22).

The F-ATPases from the thermoalkaliphile Caldalkalibacillus thermarum (23) from mycobacterial species (24, 25) and from alkaliphilic Bacilli (26, 27) exemplify classes of eubacterial enzymes with F-ATPases that can synthesize ATP but show extreme latency in hydrolyzing ATP, although a weak ATPase activity can be stimulated artificially in vitro (23–27). The modes of inhibition of the hydrolytic activity is not understood, although it has been suggested that the C. thermarum enzyme is inhibited by the γ-subunit having adopted a modified structure (28). The γ-subunit is a key component of the enzyme’s rotor.

As described here, we have investigated possible mechanisms of inhibition of the F1-ATPase from C. thermarum by studying the structure and properties of a version lacking the δ-subunit (referred to as F1-ATPase); the δ-subunit is part of the enzyme’s stator, and has no direct role in the mechanism or regulation of ATP hydrolysis. We have reinvestigated the proposal that, in the inhibited enzyme, the γ-subunit has a modified structure, and have studied a form of the enzyme with two mutations in a region of the ε-subunit where the proposed regulatory ATP molecule is bound in E. coli and G. stearothermophilus (17, 29). Our study shows that neither the γ-subunit nor the regulatory ATP bound to the ε-subunit is involved in the inhibitory mechanism, and that probably ATP hydrolysis is prevented by hydrolysis products bound to a catalytic subunit.

Results

Structure Determination.

The purified wild-type and mutant F1-ATPases from C. thermarum consist of the α-, β-, γ-, and ε-subunits (Fig. S1). The ATP hydrolysis activity of the wild-type and mutant F1-complexes was activated by lauryldimethylamine oxide [LDAO; 0.1% (vol/vol)] to a specific activity of 33–38 U/mg protein for both enzymes. The crystal structure of the wild-type enzyme (Fig. 1 A and B) was solved by molecular replacement with data to 3.0-Å resolution. The asymmetric unit contains two copies of the complex. The electron density for one copy was slightly better than for the other, but their structures are very similar, with an rmsd in main-chain atoms of 0.37 Å. Data processing and refinement statistics for both structures are summarized in Table S1. The final model of the better-defined copy of the wild-type complex (complex 1) contains the following residues: αE, 26–500; αTP, 27–501; αDP, 27–502; βE, 2–462; βTP, 2–462; βDP, 2462; γ, 3–286; and ε, 3–134. The second copy (complex 2) contains αE, 27–500; αTP, 27–501; αDP, 25–502; βE, 2–462; βTP, 2–462; βDP, 2–462; γ, 3–286; and ε, 3–134. In both structures, the nucleotide binding sites in the βDP- and βTP-subunits and in the three α-subunits are occupied by Mg-ADP. The βE-subunit contains ADP, without an accompanying magnesium ion, at 50–75% occupancy, plus density interpreted as a phosphate ion at an occupancy of 100% (Fig. S2). An ATP molecule with a magnesium ion is bound in the C-terminal α-helical domain of the ε-subunit.

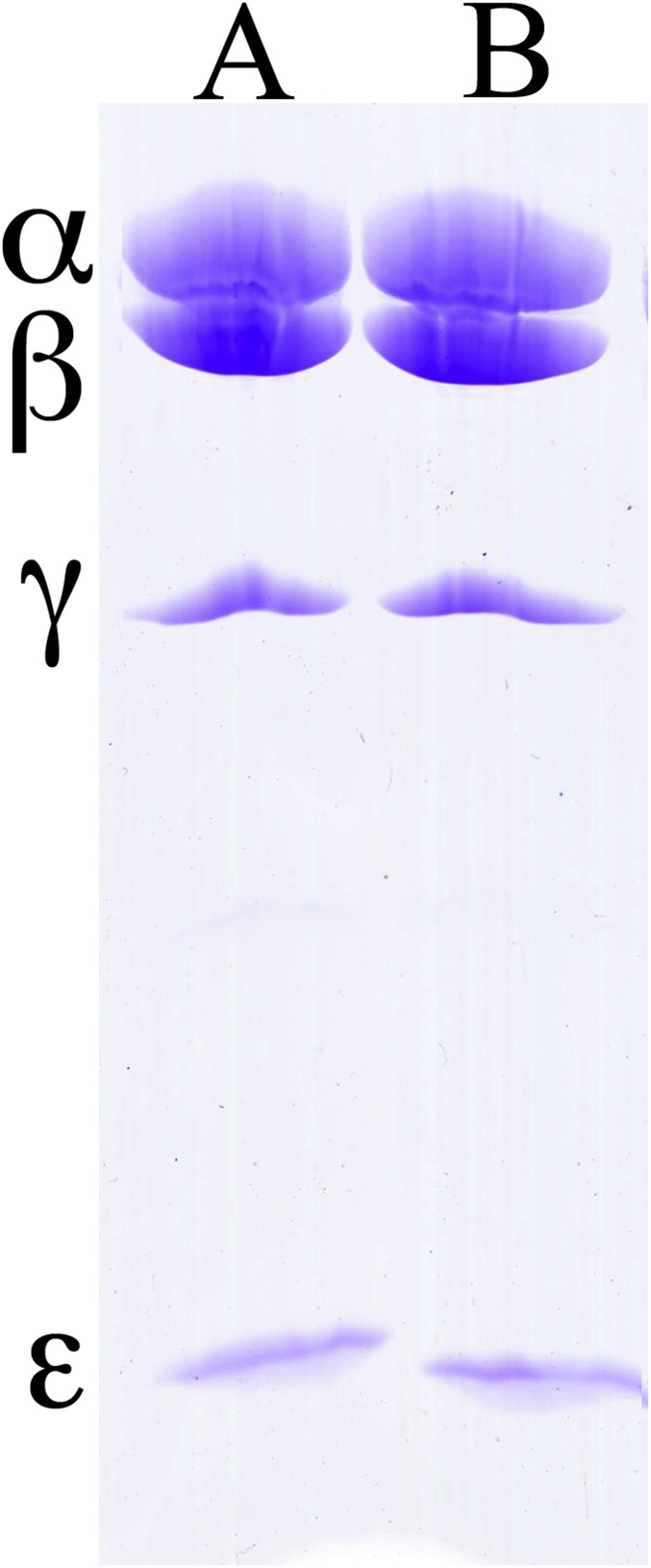

Fig. S1.

Analysis by SDS/PAGE of purified wild-type and mutant F1-ATPases from C. thermarum. The 12–22% polyacrylamide gradient gel was stained with Coomassie blue. Tracks A and B, wild-type and mutant enzymes, respectively. The positions of the subunits are indicated on the left.

Fig. 1.

Structure of the F1-ATPase from C. thermarum. (A) Side view of the wild-type structure in ribbon representation with the α-, β-, γ-, and ε-subunits in red, yellow, blue, and magenta, respectively, and bound nucleotides in black. (B) Cross-sectional view of the C-terminal domains of the α- and β-subunits, upward from the foot of the central stalk along the axis of the γ-subunit, showing the occupancy of nucleotides in nucleotide-binding domains. Green spheres represent magnesium ions, and black spheres denote a phosphate ion bound to the βE-subunit. (C) Comparison of the wild-type and mutant complexes, in blue and cyan, respectively; the structures are superimposed via their α3β3-domains. (D) Comparison of structures of F1-ATPases from C. thermarum (blue) and bovine mitochondria (pink).

Table S1.

Data collection and refinement statistics for the structures of the wild-type and mutant F1-ATPases from C. thermarum

| Parameter | Wild-type | Mutant |

| Space group | P21 | P21 |

| Unit-cell dimensions a, b, c (Å) | 147.8, 130.8, 210.4 | 148.2, 131.3, 212.0 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 64.3–3.0 (3.16–3.0) | 46.94–2.6 (2.64–2.6) |

| No. of unique reflections | 145,626 (19,744) | 220,174 (10,144) |

| Multiplicity | 3.8 (3.6) | 1.7 (1.6) |

| Completeness (%) | 95.6 (88.9) | 93.9 (87.2) |

| Rmerge* | 0.108 (0.444) | 0.056 (0.273) |

| <I/σ(I)> | 11.6 (3.0) | 10.1 (2.7) |

| B factor, from Wilson plot (Å2) | 57.3 | 27.6 |

| R factor† (%) | 0.2029 | 0.2126 |

| Free R factor‡ (%) | 0.2461 | 0.2376 |

| Rmsd of bonds (Å) | 0.011 | 0.007 |

| Rmsd of angles (°) | 1.567 | 1.057 |

Statistics for the highest-resolution bin are shown in parentheses.

Rmerge = ΣhΣi|I(h) − I(h)i|/ΣhΣiI(h)i, where I(h) is the mean weighted intensity after the rejection of outliers.

R = Σhkl||Fobs| − k|Fcalc||/Σhkl|Fobs|, where Fobs and Fcalc are the observed and calculated structure factor amplitudes, respectively.

Rfree = Σhkl⊂T||Fobs| − k|Fcalc||/Σhkl⊂T|Fobs|, where Fobs and Fcalc are the observed and calculated structure factor amplitudes, respectively, and T is the test set of data omitted from refinement (5% in this case).

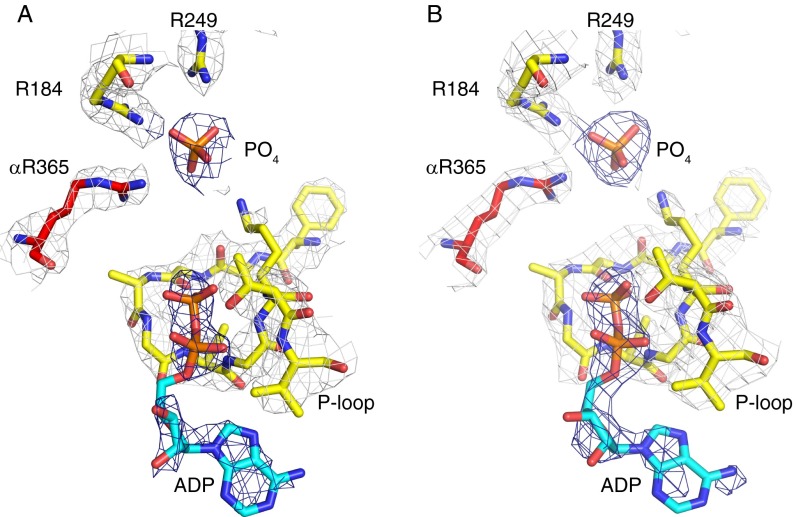

Fig. S2.

2Fo−Fc density calculated having omitted ADP and phosphate from the αE–βE–catalytic interface. A and B show the 2Fo−Fc density at 1σ in molecule 1 and molecule 2 of the wild-type enzyme, respectively. The P loop consists of residues 150–159 of the β-subunit.

The mutant F1-ATPase complex from C. thermarum was solved by molecular replacement using the α3β3-domain from the wild-type structure with data to 2.6-Å resolution (Table S1). Like the wild-type structure, the asymmetric unit of the mutant enzyme contains two copies of the complex, complexes 1 and 2, with electron densities of similar quality. The model of complex 1 contains residues αE, 27–501; αTP, 26–395, 403–501; αDP, 26–398, 401–502; βE, 1–462; βTP, 1–462; βDP, 2–462; γ, 2–286; and ε, 3–134. The resolved regions of complex 2 are almost identical, and the model contains the following residues: αE, 27–501; αTP, 26–394, 403–501; αDP, 24–399, 403–502; βE, 1–462; βTP, 1–462; βDP, 1–462; γ, 2–286; and ε, 1–134. The occupancy of nucleotides in the α- and β-subunits was the same as in the wild-type structure, with full occupancy of the ADP in the βE-subunit. Water molecules were built into the mutant structure but, because of its relatively modest resolution, only in some instances in the wild-type structure. The wild-type and mutant structures resemble each other closely, and the rmsd value of all atoms of the superimposed structures (Fig. 1C) is 0.91 Å. The higher resolution of the mutant structure revealed that the magnesium ions associated with ADP molecules in the βTP- and βDP-catalytic sites are hexacoordinated by four water molecules, the hydroxyl group of βThr158, and the oxygen atom O2B of the adenosine, as in structures of mitochondrial F1-ATPases (5–7, 30–34). Also, in the nucleotide-binding domains of the βE-subunits, there was additional density interpreted as a phosphate ion. The only significant difference between the wild-type and mutant structures is that an ATP molecule and an accompanying magnesium ion are bound to the ε-subunit of the former but not the latter. Currently, the structure of the mutant F1-ATPase from C. thermarum is the highest-resolution structure of a bacterial F1-ATPase to have been described, and it represents a significant contribution toward establishing a high-resolution molecular structure of an intact bacterial F-ATPase.

The γ-Subunit.

The γ-subunit of the F1-ATPase from the C. thermarum enzyme is folded into two α-helices in its N- and C-terminal regions (residues 1–59 and 210–286, respectively), with an intervening Rossmann fold (residues 76–189). The Rossmann fold has five β-strands with α-helices between strands 1 and 2, 2 and 3, and 3 and 4. The N- and C-terminal α-helices form an antiparallel coiled-coil that lies along the central axis of the α3β3-domain, with the extreme C-terminal region occupying the central cavity of the annular “crown.” This coiled-coil extends below the α3β3-domain, where it is associated with the Rossmann-fold domain and with the nine-stranded β-structure of the N-terminal domain of the ε-subunit.

The structure of the γ-subunit of the F1-ATPase from C. thermarum resembles closely those described previously in the structures of F1-ATPases from eubacteria and mitochondria, as expected from the conservation of sequences, especially in the C-terminal region (Fig. S3). In the structure it occupies a central position, as in other F1-ATPases. It is most closely related to the γ-subunits from E. coli (19), G. stearothermophilus (18), and Paracoccus denitrificans (10), which have almost exactly the same fold (Fig. 2 A–C). It is also similar to the γ-subunit in the bovine enzyme (Fig. 2D), but the α-helices in the coiled-coil of the bovine protein deviate from the pathway of the bacterial coiled-coil in the lower region, and the foot of the γ-subunit in C. thermarum is rotated by about 15° counterclockwise as viewed from the membrane domain of the enzyme relative to the γ-subunit in a structure of bovine F1-ATPase, where the γ- and ε-subunits are fully resolved (30). As a consequence, in the superimposed structures (Fig. 2D) the Rossmann folds are displaced relative to each other.

Fig. S3.

Alignment of sequences of γ-subunits of F-ATPases from bacteria and bovine mitochondria. Asterisks denote absolute conservation; colons indicate conservative substitution; and periods indicate similarity. BOVIN, bovine mitochondria; CALDA, C. thermarum; ECOLI, E. coli; GEOSE, G. stearothermophilus; PARDP, P. denitrificans.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of the structures of γ-subunits of the F1-ATPases in eubacteria and mitochondria. The structures shown from the side in each panel have been abstracted from the pairwise comparisons made by superimposition of the crown domain of structures of F1-ATPases. The following pairwise comparisons of γ-subunits are shown: C. thermarum from the wild-type structure in the current work (blue) versus (A) E. coli (yellow; residues 1–264), (B) G. stearothermophilus (pink; residues 2–58, 69–104,106–130, 133–162, 164–192, and 209–284), (C) P. denitrificans (light blue; residues 13–62, 64–73, 78–110, 115–143, 147–166, 170–199, and 212–289), (D) bovine mitochondria (green; residues 1–61, 67–96, and 101–272), and (E) C. thermarum from a structure of nucleotide-free F1-ATPase (orange; residues 3–49, 64–193, and 217–266).

In contrast to the likeness between the structures of the γ-subunits in bacterial and mitochondrial F1-ATPases, including that of C. thermarum determined in the present work, in a published structure of the nucleotide-free F1-ATPase from C. thermarum (28) the γ-subunit is radically different. In this earlier structure, the α-helical coiled-coil (residues 3–49 and 217–266) is displaced from the central axis of the α3β3-domain toward the β-subunits by ∼20°, and the C-terminal α-helix is truncated by disorder in its C-terminal region. It has three additional α-helical segments from residues 89–101, 119–128, and 149–161, with loops from residues 64–88, 102–188, 129–148, and 162–193. Residues 1–2, 50–63, and 194–216 were unresolved. The α-helices from residues 89–101 and 119–128 correspond to α-helices 1 and 2 in the Rossmann fold of the current structures, respectively. The many differences between this earlier structure and the current one are illustrated in Fig. 2E.

The ε-Subunit.

In the structure of the wild-type F1-ATPase from C. thermarum, the ε-subunit is in the down position with an ATP molecule bound to it. Therefore, because the enzyme is already inhibited, this mechanism of inhibition of ATP hydrolysis cannot involve the ε-subunit assuming the up position in the absence of a bound ATP molecule. The finding that the removal of the capacity of the ε-subunit to bind ATP has no effect on the inhibition of the enzyme additionally removes any possibility that the bound ATP molecule could be involved in some other unspecified inhibitory mechanism. The structures of the wild-type and mutant forms of the ε-subunit are essentially identical (rmsd for Cα-atoms 0.50 Å). In both forms, the N-terminal region (residues 3–84) has nine β-strands arranged in a β-sandwich, followed by two α-helices (residues 90–106 and 113–132) in a hairpin lying alongside the N-terminal domain. As shown in Fig. 3, they are both similar to the structures of the ε-subunit from G. stearothermophilus (rmsd for Cα-atoms 1.79 Å) (17), E. coli (rmsd 1.67 Å) (15), T. elongatus (rmsd 2.20 Å) (13), and P. denitrificans (N-terminal domain only; rmsd 1.12 Å) and to the δ-subunit of F1-ATPase from bovine mitochondria (rmsd 3.27 Å) (30).

Fig. 3.

Comparison of structures of ε-subunits of F-ATPases. (A) Superimposed structures of ε-subunits from C. thermarum (magenta, wild-type; gray, mutant), G. stearothermophilus (orange), E. coli (yellow), P. denitrificans (β-sheet domain; blue), and T. elongatus (pink). (B) The ATP binding site in the ε-subunit of the wild-type enzyme. ATP (gray) is bound to a magnesium ion (green sphere) next to C-terminal α-helices 1 and 2 of the ε-subunit (magenta). Residues Glu83, Ile88, Asp89, Arg92, Arg99, Arg123, and Arg127 (yellow) contribute to the binding site; the boxed residues were changed to alanine in the mutant form. (C) The ε-subunit in C. thermarum illustrating the surface binding site for ATP. The N-terminal β-domain and C-terminal α-helices are red and blue, respectively, and connecting loops are pink; the bound ATP molecule is yellow. (D) Superimposition of the C. thermarum ε-subunit (magenta) with ATP bound (black), and the bovine δ-subunit (cyan) bound to its cognate ε-subunit (green).

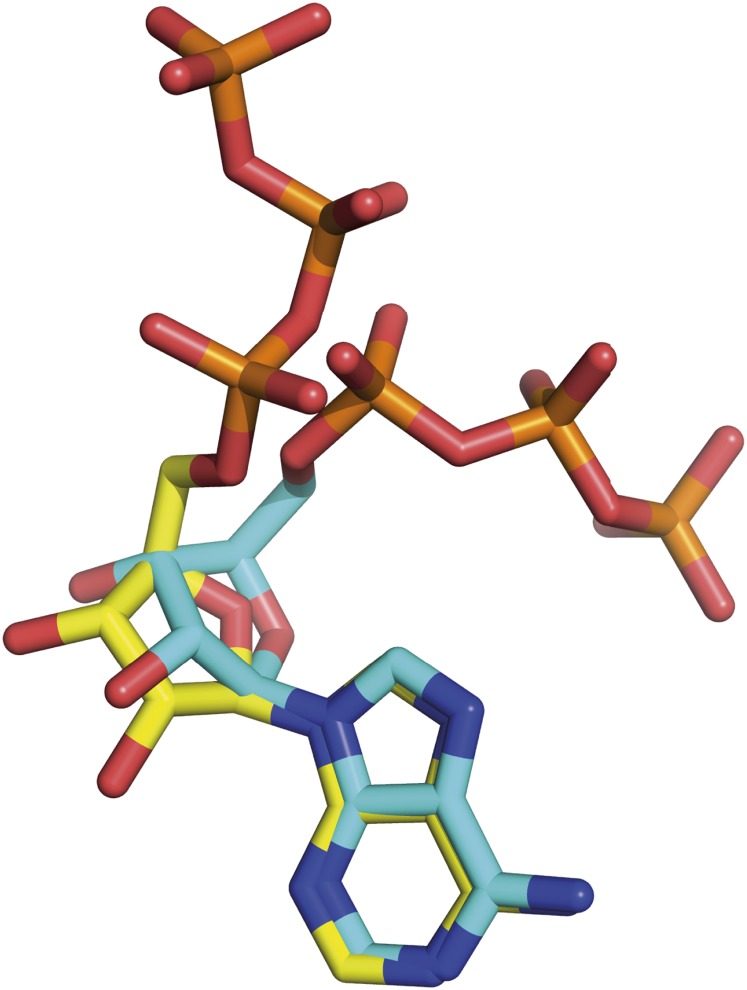

The only significant difference between the mutant and wild-type structures of the ε-subunit from C. thermarum is that an ATP molecule and an accompanying magnesium ion are bound by the two α-helices in the wild-type ε-subunit but not in the mutant form. This bound ATP has an unusual compact structure, bent by about 60° at the α-phosphate relative to the conformation, for example, of an ATP molecule bound to the βDP-subunit of the F1-ATPase from P. denitrificans (10) (Fig. S4). This conformation is characteristic of regulatory ATP molecules, whereas substrate ATP molecules are extended (35). The bound ATP is accompanied by a magnesium ion, and the O2A and O2B atoms of the ATP molecule provide two of the six ligands; the other four are almost certainly unresolved water molecules. As expected (17), both Asp89 and Arg92 help to stabilize the bound ATP. The backbone oxygen and nitrogen atoms of Asp89 interact with the adenine ring, and the side chain of Arg92 stacks on top of the adenine ring with the guanidino moiety involved in π–π interactions (Fig. 3 B and C). Residues Glu83, Ile88, and Ala93 also contribute to the adenine-binding pocket. Residue Arg92 interacts additionally with the ribose and the γ-phosphate, and residues Arg99, Arg123, and Arg127 help to coordinate the phosphates.

Fig. S4.

Comparison of the extended and compact conformations of ATP molecules bound to subunits of F-ATPases. The compact conformation is the ATP molecule bound to the ε-subunit of the F1-ATPase from C. thermarum, and the extended conformation is the ATP bound to the catalytic site in the βDP-subunit of the F-ATPase from P. denitrificans. The carbon atoms of the ATP molecules bound to the former are yellow and to the latter are light blue, with oxygen, nitrogen, and phosphorus atoms in red, dark blue, and orange, respectively.

The ε-subunit from C. thermarum is also closely related to its mitochondrial ortholog, the δ-subunit of their F-ATPases (Fig. S5). The somewhat elevated rmsd value for Cα-atoms of 3.27 Å with the bovine δ-subunit (30) reflects the slight difference in the curvature of the β-strands in the bacterial and mitochondrial orthologs (Fig. 3D). However, in structures of F1-ATPases from bovine and yeast mitochondria, an ATP molecule is not bound to the δ-subunit. Rather, the binding site in mitochondrial δ-proteins has evolved to bind the ε-subunit (which has no eubacterial equivalent). From residues 10–25 the 50-residue bovine ε-subunit is folded into a single α-helix, bound in a groove between the two domains of the bovine δ-subunit, where it occludes the pocket occupied by ATP in the bacterial ε-subunit (Fig. 3D).

Fig. S5.

Sequences in the nucleotide-binding regions of ε-subunits of bacterial F1-ATPases. The corresponding region of the orthologous δ-subunit of bovine F1-ATPase is also shown. The red residues correspond to the ATP-binding motif Ile(Leu)-Asp-X-X-Arg-Ala, plus other residues involved in ATP binding. THEEB, T. elongatus.

The α3β3-Domain.

In both mutant and wild-type forms of the enzyme from C. thermarum, the F1-ATPase and the α3β3-domain are asymmetrical, with similar architectures to the enzymes from bovine and yeast mitochondria. Their close similarity is demonstrated by the superimposition of their structures (Fig. 1D). The rmsd values for the Cα-atoms are 5.57 and 2.71 Å, respectively, for the F1-ATPases and 1.28 and 1.24 Å for the corresponding α3β3-domains.

A striking feature of both the wild-type and mutant structures of the C. thermarum F1-ATPase is that the catalytic site of the βE-subunit contains an ADP molecule without an associated magnesium ion, and also additional electron density interpreted as a phosphate ion (Fig. 4 A and B). As in other structures of F1-ATPase, the adenine moiety is bound in a pocket provided by the side chains of residues Tyr345 and Phe424, and the diphosphate part of ADP is associated with the P-loop sequence, which is Gly-Ala-Gly-Val-Gly-Lys-Thr (residues 152–158) in C. thermarum. The side chain of the “arginine finger” residue α-Arg365 (equivalent to bovine α-Arg373) (Fig. 4 C–F), an essential component of the catalytic mechanism, also points toward the bound phosphate, although there is evidence of an alternate conformation, as in the ground-state structure of the bovine F1-ATPase (Fig. 4F). The phosphate-binding pocket contains residues Lys157, Arg184, Asp245, Asn246, and Arg249, with their side chains interacting with the oxygen atoms of the phosphate, as usual. The phosphate itself is about 7 Å from where the γ-phosphate of an ATP molecule would be if bound to a βE-subunit. The corresponding electron density was interpreted as phosphate rather than sulfate, as the enzyme had not been exposed to any oxyanions. The purification buffers included 1 mM Mg-ADP but the crystallization buffers were devoid of nucleotide, and therefore it is likely that both the bound ADP and the phosphate originated in the E. coli strain used to overexpress the enzymes.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of the βE-catalytic site in the F1-ATPase from C. thermarum with those in various structures of bovine F1-ATPase. (A) The βE-catalytic site in the wild-type enzyme from C. thermarum. (B) Comparison of the βE-catalytic sites in the wild-type (yellow) and mutant (blue) forms of the enzyme from C. thermarum. (C and D) The βE-catalytic sites in bovine F1-ATPase crystallized in the presence of phosphonate (C) and thiophosphate (D). (E) The complex of bovine F1-ATPase with the c8 ring. (F) The ground-state structure of bovine F1-ATPase.

The presence of both a bound ADP molecule (lacking an accompanying magnesium ion) and a bound phosphate ion in the βE-subunit of an F1-ATPase is unique among reported structures of the enzyme. In structures of bovine F1-ATPase, the βE-subunit is occupied by an ADP molecule, and no magnesium ion, when crystals were grown in the presence of the magnesium chelator phosphonate (33) (Fig. 4C), and the phosphate analog thiophosphate (34) occupies a similar position to the phosphate in the current structures (Fig. 4D). Phosphate has been found also in a similar position in structures of yeast F1-ATPase (36), the bovine F1–c8 ring complex (37) (Fig. 4E), and bovine F1-ATPase inhibited with dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (30). In the ground-state structure of bovine F1-ATPase determined at 1.9-Å resolution (38), neither nucleotide nor phosphate occupied the βE-subunit (Fig. 4F).

Discussion

The proposal that the ATP hydrolase activity of the F1-ATPase from C. thermarum is inhibited by the γ-subunit adopting an extensively modified structure (28) has been reexamined. In the inhibited complex, the γ-subunit has a structure closely resembling those of γ-subunits in catalytically active F1-ATPases from other bacterial and mitochondrial sources. It is unlikely that the differences can be attributed to the earlier structure of enzyme from C. thermarum being made with enzyme devoid of bound nucleotides (28) because in a structure of the F1-ATPase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae, also determined with no bound nucleotides (39), the structure of the γ-subunit is very similar (rmsd 1.12 Å) to that determined when bound nucleotides were present in the same enzyme (36). Therefore, there is no good structural reason to invoke the remodeling of the γ-subunit as the inhibitory mechanism. In addition, the structure of the α3β3-domain and the penetrant region of the γ-subunit, which lies along its central axis, do not differ in any discernible way from those of active F1-ATPases. Therefore, the basis of the inhibitory mechanism is probably associated with some other features of the enzyme.

One possibility that has been considered is that the ε-subunit may contribute to this inhibitory mechanism as reported in other bacterial F-ATPases (11–13, 17–21). In the active F1-ATPase from G. stearothermophilus, for example, the ε-subunit has been observed in the down position with the C-terminal α-helical hairpin, and bound ATP, alongside the N-terminal β-domain (17). It has been proposed that when the proton-motive force and ATP concentration are low, the ATP molecule leaves the ε-subunit, allowing its two α-helices to dissociate from the β-domain, forming the inhibitory up conformation (17–20, 40). In this conformation, the α-helices penetrate into the catalytic domain along the axis of the coiled-coil in the γ-subunit. In the structure of the inhibited wild-type F1-ATPase from C. thermarum the ε-subunit is down, with an ATP molecule bound to it. Therefore, to test the possibility that the ATP molecule bound to the ε-subunit plays some hitherto unconsidered role in inhibiting the C. thermarum F1-ATPase, the ATP-binding capacity was removed by mutation. The enzyme remained inactive, and the structure of the ε-subunit was unchanged with its C-terminal α-helices still down. Therefore, it is unlikely that the ε-subunit, and its bound ATP molecule, contributes to this inhibitory mechanism.

A characteristic feature of bacterial F-ATPases with latent hydrolytic activity is that ATP hydrolysis can be activated artificially in vitro (26, 27) and, for example, LDAO activates the C. thermarum F1-ATPase (41). Removal of the C-terminal domain of the ε-subunit activated the enzyme partially (41), and LDAO activated this mutated enzyme to its fullest extent. LDAO also stimulates the activities of F1-ATPases that can hydrolyze ATP, by releasing ADP from a catalytic site (42, 43). Thus, it is possible that in vitro activation of the C. thermarum F1-ATPase with LDAO (41) may proceed by a combination of perturbation of the interaction between the ε-subunit and α3β3-domain (41, 44, 45) and an effect on one or more catalytic sites.

The most striking difference between the structures of the inactive C. thermarum wild-type and mutant states is that the most open of the three catalytic β-subunits, the βE-subunit, is occupied by both an ADP molecule, with no associated magnesium ion, and by a phosphate ion bound in a position 7 Å from the γ-phosphate of a bound ATP molecule. A similar occupancy of ADP and phosphate in the βE-subunit has never been observed in any of the many structures of states derived from an active F1-ATPase, suggesting that it may be the basis of the mechanism of inhibition of ATP hydrolysis in C. thermarum. Following the hydrolysis of an ATP molecule in a closed catalytic site of F1-ATPase, as the site opens in response to rotation of the γ-subunit driven by ATP hydrolysis in another catalytic site, the order of product release is not known, although it appears that the first product to leave as the catalytic site opens is the magnesium ion. However, there are conflicting data about whether ADP is released before phosphate or vice versa, although in other NTPases, ADP leaves last (46). Thus, one interpretation of the current information is that after ATP hydrolysis in the βDP-site that subsequently becomes the observed βE-site in the structure, the magnesium ion leaves followed by ADP, which then rebinds in a concentration-dependent manner. Another possibility is that the magnesium ion and phosphate leave after hydrolysis, and phosphate then rebinds in a concentration-dependent manner. The current structure favors the former mechanism. Thus, quantitative measurement of the affinities of ADP and phosphate and the structure of the enzyme artificially activated with LDAO would help to test these interpretations.

Knowledge of the mechanism of inhibition of the C. thermarum and other bacterial F-ATPases similarly inhibited in ATP hydrolysis could have practical benefits. For example, the F-ATPase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis is a validated drug target for treatment of tuberculosis, and knowledge of the mechanism of inhibition of ATP synthesis in this organism, and in other pathogenic bacteria, could provide new opportunities for drug development.

Materials and Methods

For purification and crystallization of bacterial F1-ATPase, the C. thermarum F1-ATPase (wild-type and mutant) was expressed from versions of plasmid pTrc99A (47) with a His10 tag and a cleavage site for the tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease at the N terminus of subunit ε. The enzyme was purified by nickel affinity chromatography and cleaved on-column with TEV protease. Crystals grown by the microbatch method were cryocooled, and data were collected at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility, Grenoble, France. For full details of these processes and of the structure determination and analysis, see SI Materials and Methods.

SI Materials and Methods

Expression Plasmids.

With the exception of atpH encoding the δ-subunit, the genes for the subunits of Caldalkalibacillus thermarum F1-ATPase had been cloned into the expression plasmid pTrc99A (47). The resulting plasmid pTrcα-ε (containing atpAGDC), encoding the α-, γ-, β-, and ε-subunits, of the F1 sector of the ATP synthase from C. thermarum was used to create plasmids for the expression of both the wild-type and mutant F1-ATPases. To facilitate purification of the wild-type and mutant complexes, a decahistidine tag and a cleavage site for the protease from TEV were introduced by PCR overlap mutagenesis into the N terminus of atpC from the plasmid pTrcα-ε. Two pairs of primers, εHis10Fwd (forward) (5′-CACCATCACCATCACCATCACCATCACCATGAGAATCTTTATTTTCAG GGCGCAACTGTTCAAGTTGATATCGTCAC-3′) with pTrc99ARev (reverse) (5′-CCGCTTCTGCGTTCTGATTT-3′) and εHis10Rev (5′-GCCCTGAAAATAAAGATTCTCATGGTGATGGTGATGGTGATGGTGATG GTGCATTGTTTATCCTCCCCTATCTCAG-3′) with primer AflIIFwd (5′-CACCCAGGCCAAATTAAACCGTGGTG-3′), were used to generate DNA fragments with 10 histidine codons and a TEV protease cleavage site. These overlapping fragments were then used for PCR overlap extension with the external primers AflIIFwd and pTrc99ARev, and the resulting product was digested with NotI and SalI and then cloned into plasmid pTrcα-ε digested with NotI and SalI. The resulting plasmid pTrcF1ΔδHisTev contained the wild-type F1-ATPase from C. thermarum with a decahistidine tag and a TEV protease cleavage site on the N terminus of the ε-subunit.

The mutations Asp89Ala and Arg92Ala were introduced into atpC in pTrcF1ΔδHisTev by PCR using two pairs of primers, NotIFwd (5′-GATATTTACAATGCGATTACC-3′) with atpCRP1 (5′-TTTGGCGGCCTCGACAGCGATTTCTTCCGGCAATTCGGC-3′) and atpCFP2 (5′-GAAATCGCTGTCGAGGCCGCCAAAAAGGCAAAGGCGCGC-3′) with pTrc99ARev (5′-CCGCTTCTGCGTTCTGATTT-3′). The resulting overlapping fragments were joined by PCR overlap extension with the primers NotIFwd and pTrc99ARev. The product was cloned into the NotI and SalI sites in pTrcF1ΔδHisTev, generating the plasmid pTrcF1ΔδHisTev-(D89A, R92A). All cloning was conducted in Escherichia coli XL1-Blue cells (Agilent), and the enzyme used for all PCR was the DNA polymerase from Thermococcus kodakaraensis (Merck Millipore). All regions amplified by PCR were confirmed by DNA sequencing. For overexpression of the F1-ATPase, the plasmids pTrcF1ΔδHisTev and pTrcF1ΔδHisTev-(D89A, R92A) were transformed into a strain of E. coli C41 known as E. coli C41(Δunc), where the unc operon, encoding the E. coli F-ATPase complex, had been disrupted by the insertion of a chloramphenicol resistance gene.

Purification of Wild-Type and Mutant F1-ATPases.

Cells of transformed E. coli C41(Δunc) were grown at 37 °C in an Applikon ADI 1075 fermenter (100-L maximum capacity) in 2× tryptone-yeast extract broth containing ampicillin (100 µg/mL). When the optical density of the culture at 600 nm had reached 0.6, 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-1-thiogalactosylpyranoside was added, and cell growth was continued for a further 16 h at 25 °C. The yield of wet cells was 9 g/L. Cells were suspended in six volumes (600 mL for 100 g cells) of buffer consisting of 50 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 8.0), 10% (vol/vol) glycerol, and 2 mM MgCl2. They were disrupted by a single passage at 30 kpsi through a Constant Systems cell disruptor, and the effluent was centrifuged (150,000 × g, 45 min, 4 °C). The supernatant was heated at 65 °C for 30 min with agitation every 10 min, and insoluble material was removed by centrifugation (50,000 × g, 25 min, 4 °C). The supernatant was filtered (0.22-μm pores; Millipore), and loaded onto a nickel affinity column (5 mL; GE Healthcare) equilibrated in buffer A [20 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 8.0, 10% (vol/vol) glycerol, 40 mM imidazole, 2 mM MgCl2, 300 mM NaCl, 1 mM ADP, and EDTA-free protease inhibitor mixture tablets (Roche)]. The protein was eluted at a flow rate of 1 mL/min with the same buffer, except that the concentration of imidazole was 200 mM (buffer B). The protein content of fractions (1 mL) was analyzed by SDS/PAGE on 12–15% polyacrylamide gradient gels. The fractions containing F1-ATPase were pooled. TEV protease (AcTEV; Thermo Fisher) was added (1:5, wt/wt), and the solution was dialyzed overnight at room temperature with a 3,500-kDa molecular-mass cutoff membrane (Spectra) against buffer consisting of 50 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 8.0), 10% (vol/vol) glycerol, 2 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM Tris-2-carboxyethylphosphine. The retained solution was concentrated to 5 mL with a Vivaspin 6 concentrator (molecular-mass cutoff of 100,000 kDa; Sartorius Stedim) and applied to a nickel affinity column equilibrated in buffer A. All subsequent concentration steps were performed with Vivaspin 6 concentrators (molecular-mass cutoff of 100,000 kDa; Sartorius Stedim). Cleaved F1-ATPase lacking the His tag was recovered in the breakthrough fractions, and uncleaved enzyme was eluted with buffer B. Cleaved enzyme was pooled, concentrated to 2 mL, and centrifuged (120,000 × g, 30 min, 4 °C). The supernatant was applied to a column of Superdex 200 (120 mL; GE Healthcare) equilibrated in buffer containing 20 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 8.0), 10% (vol/vol) glycerol, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM ADP, and 100 mM NaCl and eluted at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The ultraviolet absorption of the effluent was monitored at 280 nm. Fractions (1 mL) containing the wild-type F1-ATPase and the F1-complex with the mutations Asp89Ala and Arg92Ala were analyzed by SDS/PAGE, and the purest fractions were pooled. Their protein concentrations were measured by the bicinchoninic assay (Pierce) and adjusted to a concentration of 10 mg/mL. F1-ATPase activity was measured at 45 °C using an ATP-regenerating assay as described previously with 0.1% (vol/vol) LDAO (41).

Crystal Growth.

Samples of the concentrated solutions of the wild-type and mutant enzymes (10 mg/mL) were centrifuged (120,000 × g, 30 min, 4 °C) and crystallized at 23 °C by the microbatch method under paraffin oil. For the wild-type enzyme, the drops consisted of the concentrated solution of enzyme (2 µL) plus a solution (2 µL) containing 8.75% (wt/vol) polyethylene glycol 1500, 16.75% (wt/vol) polyethylene glycol 4000, and 100 mM Bis-Tris (pH 7.8). For the mutant complex, the drops consisted of the protein solution (2 μL) plus a solution (2 μL) containing 26.9% (wt/vol) polyethylene glycol 4600 and 100 mM Bis-Tris (pH 6.6). Crystals of both complexes were harvested after 30 d of growth. For the crystals of the wild-type enzyme, a solution with the same composition as the mother liquor, plus an additional 2% (wt/vol) PEG and 10% (vol/vol) glycerol, was added to drops containing crystals. After 2 min, a sample (10 μL) of the drop was mixed with harvest solution (10 μL) containing 20% (vol/vol) glycerol. This process was repeated until the concentration of glycerol in the drop was 20% (vol/vol). Similarly, with the crystals of the mutant enzyme, a solution with the same composition as the mother liquor plus an additional 2% (wt/vol) PEG and 25% (vol/vol) glycerol was added to drops containing crystals. The process was repeated until the concentration of glycerol in the drops was 25% (vol/vol), after which individual crystals were vitrified in liquid nitrogen.

Data Collection and Structure Determination.

X-ray diffraction data were collected at 100 K from cryoprotected crystals with a Mar mosaic charge-coupled detector (Rayonix) at a wavelength of 0.8726 Å on beamline ID23-2 at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility, Grenoble, France. To minimize radiation damage to crystals of the mutant complex, a helical line scan was used. Diffraction images were integrated with MOSFLM (48, 49), and the data were reduced with SCALA (50) and TRUNCATE (51). With the wild-type enzyme, molecular replacement with the α3β3-domain from the structure of azide-inhibited bovine F1-ATPase (PDB ID code 2CK3) was carried out with Phaser (52). Nucleotides, magnesium ions, and water molecules were removed from the model. Rigid-body refinement and restrained refinement with noncrystallographic symmetry restraints were performed with REFMAC5 (53). Manual rebuilding was performed with Coot (54), alternating with refinement performed with REFMAC5. For calculations of Rfree, 5% of the diffraction data were excluded from the refinement. Stereochemistry was assessed with MolProbity (55), and images of structures and electron density maps were prepared with PyMOL (56). The solution of the structure of the mutant complex was carried out in the same way, except that the molecular replacement model was the wild-type structure without the ε-subunit.

Comparison of Structures.

The structures of the wild-type and mutant forms of the F1-ATPase from C. thermarum were compared with each other, and the wild-type structures only were compared with those of F1-ATPases from other species. The structures were superimposed pairwise, with no cycles of refinement, in PyMOL (56) via their “crown” domains (residues 25–90 and 22–80 in C. thermarum α- and β-subunits, respectively), their α3β3-domains, or the ε-subunits. The rmsd values given above are for Cα-atoms unless stated otherwise. Comparisons of the γ-subunit were made with the crown domain-aligned F1-ATPases from E. coli (PDB ID code 3OAA; crown residues α 25–90, β 22–80) (19), Geobacillus stearothermophilus (PDB ID code 4XD7; crown residues α 25–90, β 22–80) (18), P. denitrificans (PDB ID code 5DN6; crown residues α 25–90, β 22–80) (10), and bovine mitochondria (PDB ID code 1E79; crown residues α 25–90, β 22–80) (30) and with a published structure of F1-ATPase from C. thermarum (PDB ID code 2QE7; crown residues α 25–90, β 22–80) (28). The ε-subunits from G. stearothermophilus (PDB ID code 2E5Y) (17), E. coli (PDB ID code 1AQT) (15), Thermosynechococcus elongatus (PDB ID code 2RQ6) (13), and Paracoccus denitrificans (PDB ID code 5DN6; N-terminal domain only; the α-helices were not resolved in this structure) and the δ-subunit of F1-ATPase from bovine mitochondria (PDB ID code 1E79) (30) were superimposed pairwise, with no cycles of refinement, in PyMOL (56). Images of the nucleotide binding sites of βE-subunits were taken from the structures of bovine F1-ATPase inhibited with phosphonate and thiophosphate (PDB ID codes 4ASU and 4YXW, respectively) (33, 34), the bovine F1–c8 ring complex (PDB ID code 2XND) (37), and the ground state of bovine F1-ATPase (PDB ID code 2JDI) (38).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. D. M. Rees for preparing Escherichia coli C41(Δunc), and the beamline staff at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility for their help. This work was supported by the Medical Research Council UK by Grants MC_U1065663150 (to J.E.W.) and MC_U105184325 (to A.G.W.L.), and by Programme Grant MR/M009858/1 (to J.E.W.). G.M.C. was supported by a James Cook Fellowship from the Royal Society of New Zealand and the Health Research Council of New Zealand.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data deposition: The crystallography, atomic coordinates, and structure factors reported in this paper have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID codes 5HKK and 5IK2).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1612035113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Walker JE. The ATP synthase: The understood, the uncertain and the unknown. Biochem Soc Trans. 2013;41(1):1–16. doi: 10.1042/BST20110773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nalin CM, McCarty RE. Role of a disulfide bond in the γ subunit in activation of the ATPase of chloroplast coupling factor 1. J Biol Chem. 1984;259(11):7275–7280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hisabori T, Konno H, Ichimura H, Strotmann H, Bald D. Molecular devices of chloroplast F(1)-ATP synthase for the regulation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1555(1–3):140–146. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(02)00269-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pullman ME, Monroy GC. A naturally occuring inhibitor of mitochondrial adenosine triphosphatase. J Biol Chem. 1963;238(11):3762–3769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gledhill JR, Montgomery MG, Leslie AGW, Walker JE. How the regulatory protein, IF(1), inhibits F(1)-ATPase from bovine mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(40):15671–15676. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707326104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robinson GC, et al. The structure of F1-ATPase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae inhibited by its regulatory protein IF1. Open Biol. 2013;3(2):120164. doi: 10.1098/rsob.120164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bason JV, Montgomery MG, Leslie AGW, Walker JE. Pathway of binding of the intrinsically disordered mitochondrial inhibitor protein to F1-ATPase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(31):11305–11310. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1411560111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morales-Ríos E, et al. A novel 11-kDa inhibitory subunit in the F1FO ATP synthase of Paracoccus denitrificans and related α-proteobacteria. FASEB J. 2010;24(2):599–608. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-137356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Serrano P, Geralt M, Mohanty B, Wüthrich K. NMR structures of α-proteobacterial ATPase-regulating ζ-subunits. J Mol Biol. 2014;426(14):2547–2553. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2014.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morales-Rios E, Montgomery MG, Leslie AGW, Walker JE. Structure of ATP synthase from Paracoccus denitrificans determined by X-ray crystallography at 4.0 Å resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(43):13231–13236. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1517542112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laget PP, Smith JB. Inhibitory properties of endogenous subunit epsilon in the Escherichia coli F1 ATPase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1979;197(1):83–89. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(79)90222-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kato-Yamada Y, et al. ε subunit, an endogenous inhibitor of bacterial F(1)-ATPase, also inhibits F(0)F(1)-ATPase. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(48):33991–33994. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.48.33991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yagi H, et al. Structural and functional analysis of the intrinsic inhibitor subunit ε of F1-ATPase from photosynthetic organisms. Biochem J. 2009;425(1):85–94. doi: 10.1042/BJ20091247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilkens S, Dahlquist FW, McIntosh LP, Donaldson LW, Capaldi RA. Structural features of the ε subunit of the Escherichia coli ATP synthase determined by NMR spectroscopy. Nat Struct Biol. 1995;2(11):961–967. doi: 10.1038/nsb1195-961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uhlin U, Cox GB, Guss JM. Crystal structure of the ε subunit of the proton-translocating ATP synthase from Escherichia coli. Structure. 1997;5(9):1219–1230. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(97)00272-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilkens S, Capaldi RA. Solution structure of the ε subunit of the F1-ATPase from Escherichia coli and interactions of this subunit with β subunits in the complex. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(41):26645–26651. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.41.26645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yagi H, et al. Structures of the thermophilic F1-ATPase ε subunit suggesting ATP-regulated arm motion of its C-terminal domain in F1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(27):11233–11238. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701045104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shirakihara Y, et al. Structure of a thermophilic F1-ATPase inhibited by an ε-subunit: Deeper insight into the ε-inhibition mechanism. FEBS J. 2015;282(15):2895–2913. doi: 10.1111/febs.13329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cingolani G, Duncan TM. Structure of the ATP synthase catalytic complex (F(1)) from Escherichia coli in an autoinhibited conformation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18(6):701–707. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shah NB, Hutcheon ML, Haarer BK, Duncan TM. F1-ATPase of Escherichia coli: The ε-inhibited state forms after ATP hydrolysis, is distinct from the ADP-inhibited state, and responds dynamically to catalytic site ligands. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(13):9383–9395. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.451583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shah NB, Duncan TM. Aerobic growth of Escherichia coli is reduced and ATP synthesis is selectively inhibited when five C-terminal residues are deleted from the ε subunit of ATP synthase. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(34):21032–21041. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.665059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taniguchi N, Suzuki T, Berney M, Yoshida M, Cook GM. The regulatory C-terminal domain of subunit ε of FoF1 ATP synthase is dispensable for growth and survival of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2011;193(8):2046–2052. doi: 10.1128/JB.01422-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cook GM, et al. Purification and biochemical characterization of the F1Fo-ATP synthase from thermoalkaliphilic Bacillus sp. strain TA2.A1. J Bacteriol. 2003;185(15):4442–4449. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.15.4442-4449.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakagawa H, Lee SH, Kalra VK, Brodie AF. Trypsin-induced changes in the orientation of latent ATPase in protoplast ghosts from Mycobacterium phlei. J Biol Chem. 1977;252(22):8229–8234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haagsma AC, Driessen NN, Hahn MM, Lill H, Bald D. ATP synthase in slow- and fast-growing mycobacteria is active in ATP synthesis and blocked in ATP hydrolysis direction. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2010;313(1):68–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2010.02123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoffmann A, Dimroth P. The ATPase of Bacillus alcalophilus. Purification and properties of the enzyme. Eur J Biochem. 1990;194(2):423–430. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb15635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hicks DB, Krulwich TA. Purification and reconstitution of the F1F0-ATP synthase from alkaliphilic Bacillus firmus OF4. Evidence that the enzyme translocates H+ but not Na+ J Biol Chem. 1990;265(33):20547–20554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stocker A, Keis S, Vonck J, Cook GM, Dimroth P. The structural basis for unidirectional rotation of thermoalkaliphilic F1-ATPase. Structure. 2007;15(8):904–914. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kato S, Yoshida M, Kato-Yamada Y. Role of the ε subunit of thermophilic F1-ATPase as a sensor for ATP. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(52):37618–37623. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707509200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gibbons C, Montgomery MG, Leslie AGW, Walker JE. The structure of the central stalk in bovine F(1)-ATPase at 2.4 Å resolution. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7(11):1055–1061. doi: 10.1038/80981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gledhill JR, Montgomery MG, Leslie AGW, Walker JE. Mechanism of inhibition of bovine F1-ATPase by resveratrol and related polyphenols. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(34):13632–13637. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706290104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bowler MW, Montgomery MG, Leslie AGW, Walker JE. How azide inhibits ATP hydrolysis by the F-ATPases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(23):8646–8649. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602915103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rees DM, Montgomery MG, Leslie AGW, Walker JE. Structural evidence of a new catalytic intermediate in the pathway of ATP hydrolysis by F1-ATPase from bovine heart mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(28):11139–11143. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1207587109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bason JV, Montgomery MG, Leslie AGW, Walker JE. How release of phosphate from mammalian F1-ATPase generates a rotary substep. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(19):6009–6014. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1506465112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lu S, et al. The structural basis of ATP as an allosteric modulator. PLoS Comput Biol. 2014;10(9):e1003831. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kabaleeswaran V, Puri N, Walker JE, Leslie AGW, Mueller DM. Novel features of the rotary catalytic mechanism revealed in the structure of yeast F1 ATPase. EMBO J. 2006;25(22):5433–5442. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Watt IN, Montgomery MG, Runswick MJ, Leslie AGW, Walker JE. Bioenergetic cost of making an adenosine triphosphate molecule in animal mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(39):16823–16827. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011099107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bowler MW, Montgomery MG, Leslie AGW, Walker JE. Ground state structure of F1-ATPase from bovine heart mitochondria at 1.9 Å resolution. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(19):14238–14242. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700203200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kabaleeswaran V, et al. Asymmetric structure of the yeast F1 ATPase in the absence of bound nucleotides. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(16):10546–10551. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M900544200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Suzuki T, et al. F0F1-ATPase/synthase is geared to the synthesis mode by conformational rearrangement of ε subunit in response to proton motive force and ADP/ATP balance. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(47):46840–46846. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307165200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Keis S, Stocker A, Dimroth P, Cook GM. Inhibition of ATP hydrolysis by thermoalkaliphilic F1Fo-ATP synthase is controlled by the C terminus of the epsilon subunit. J Bacteriol. 2006;188(11):3796–3804. doi: 10.1128/JB.00040-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jault JM, et al. The α3β3γ complex of the F1-ATPase from thermophilic Bacillus PS3 containing the αD261N substitution fails to dissociate inhibitory MgADP from a catalytic site when ATP binds to noncatalytic sites. Biochemistry. 1995;34(50):16412–16418. doi: 10.1021/bi00050a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nakanishi-Matsui M, et al. Stochastic high-speed rotation of Escherichia coli ATP synthase F1 sector: The epsilon subunit-sensitive rotation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(7):4126–4131. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510090200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lötscher HR, deJong C, Capaldi RA. Interconversion of high and low adenosinetriphosphatase activity forms of Escherichia coli F1 by the detergent lauryldimethylamine oxide. Biochemistry. 1984;23(18):4140–4143. doi: 10.1021/bi00313a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dunn SD, Tozer RG, Zadorozny VD. Activation of Escherichia coli F1-ATPase by lauryldimethylamine oxide and ethylene glycol: Relationship of ATPase activity to the interaction of the ε and β subunits. Biochemistry. 1990;29(18):4335–4340. doi: 10.1021/bi00470a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nitta R, Okada Y, Hirokawa N. Structural model for strain-dependent microtubule activation of Mg-ADP release from kinesin. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15(10):1067–1075. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stocker A, Keis S, Cook GM, Dimroth P. Purification, crystallization, and properties of F1-ATPase complexes from the thermoalkaliphilic Bacillus sp. strain TA2.A1. J Struct Biol. 2005;152(2):140–145. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leslie AGW. The integration of macromolecular diffraction data. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2006;62(Pt 1):48–57. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905039107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Battye TG, Kontogiannis L, Johnson O, Powell HR, Leslie AG. iMOSFLM: A new graphical interface for diffraction-image processing with MOSFLM. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2011;67(Pt 4):271–281. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910048675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Evans P. Scaling and assessment of data quality. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2006;62(Pt 1):72–82. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905036693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.French G, Wilson K. On the treatment of negative intensity observations. Acta Crystallogr A. 1978;34:517–525. [Google Scholar]

- 52.McCoy AJ, et al. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Crystallogr. 2007;40(Pt 4):658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Murshudov GN, et al. REFMAC5 for the refinement of macromolecular crystal structures. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2011;67(Pt 4):355–367. doi: 10.1107/S0907444911001314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66(Pt 4):486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen VB, et al. MolProbity: All-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66(Pt 1):12–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Schrodinger LLC (2015) The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.8. Available at pymol.org. Accessed August 31, 2016.