Significance

Elevated expression of the iron–sulfur (Fe-S) protein nutrient-deprivation autophagy factor-1 (NAF-1) is associated with the progression of multiple cancer types. Here we demonstrate that the lability of the Fe-S cluster of NAF-1 plays a key role in promoting breast cancer cell proliferation, tumor growth, and resistance of cancer cells to oxidative stress. Our study establishes an important role for the unique 3Cys-1His Fe-S cluster coordination structure of NAF-1 in promoting the development of breast cancer tumors and suggests the potential use of drugs that suppress NAF-1 accumulation or stabilize its cluster in the treatment of cancers that display high expression levels of NAF-1.

Keywords: Fe-S, ROS, NEET, cancer, NAF-1

Abstract

Iron–sulfur (Fe-S) proteins are thought to play an important role in cancer cells mediating redox reactions, DNA replication, and telomere maintenance. Nutrient-deprivation autophagy factor-1 (NAF-1) is a 2Fe-2S protein associated with the progression of multiple cancer types. It is unique among Fe-S proteins because of its 3Cys-1His cluster coordination structure that allows it to be relatively stable, as well as to transfer its clusters to apo-acceptor proteins. Here, we report that overexpression of NAF-1 in xenograft breast cancer tumors results in a dramatic augmentation in tumor size and aggressiveness and that NAF-1 overexpression enhances the tolerance of cancer cells to oxidative stress. Remarkably, overexpression of a NAF-1 mutant with a single point mutation that stabilizes the NAF-1 cluster, NAF-1(H114C), in xenograft breast cancer tumors results in a dramatic decrease in tumor size that is accompanied by enhanced mitochondrial iron and reactive oxygen accumulation and reduced cellular tolerance to oxidative stress. Furthermore, treating breast cancer cells with pioglitazone that stabilizes the 3Cys-1His cluster of NAF-1 results in a similar effect on mitochondrial iron and reactive oxygen species accumulation. Taken together, our findings point to a key role for the unique 3Cys-1His cluster of NAF-1 in promoting rapid tumor growth through cellular resistance to oxidative stress. Cluster transfer reactions mediated by the overexpressed NAF-1 protein are therefore critical for inducing oxidative stress tolerance in cancer cells, leading to rapid tumor growth, and drugs that stabilize the NAF-1 cluster could be used as part of a treatment strategy for cancers that display high NAF-1 expression.

Recent studies identified a possible link between Fe-S metabolism and cancer development (1–3). Overexpression of the microRNA miR-210 that suppresses the expression of the Fe-S cluster scaffold protein ISCU was, for example, detected in most solid tumors and linked to enhanced reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and adverse prognosis in patients with breast cancer (1). Disrupted expression of frataxin, another protein involved in Fe-S biogenesis, in hepatocytes of transgenic mice similarly led to impaired mitochondrial function, oxidative stress, and the development of multiple hepatic tumors (2). Moreover, ISCU and frataxin are regulated at the transcriptional level by p53 controlling the levels of ROS in cells (3). Because the level of ROS in cancer cells is kept at a moderately high level, the tumorigenic level (4), it is plausible that alterations in Fe-S metabolism, e.g., by enhanced or suppressed expression of different proteins involved in Fe-S metabolism, could play a key biochemical and regulatory role in cancer cells, promoting cell proliferation and enhancing tumorigenicity (1–5).

NEET proteins compose a unique class of iron–sulfur (2Fe-2S) proteins (6). Their clusters are coordinated by a 3Cys:1His structure that allows it to be both relatively stable, as well as to transfer to apo-acceptor proteins. This unique feature of NEET proteins is likely controlled by the NEET’s 2Fe-2S’s coordinating His that is positioned at the protein surface and can undergo protonation that destabilizes the cluster and enables its transfer (6). Recent studies implicated NEET proteins in a diverse array of biological processes and diseases. Localized to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and mitochondria, the NEET protein nutrient-deprivation autophagy factor-1 (NAF-1) (encoded by CISD2) was, for example, implicated in the regulation of autophagy (6, 7), apoptosis (8), ER–calcium signaling (6, 9), and iron and ROS homeostasis (10, 11). NAF-1 was also linked to neurodegenerative diseases, skeletal muscle maintenance, and aging (12, 13). Localized to the mitochondrial outer membrane, the NEET protein mNT (encoded by CISD1) was similarly implicated in diabetes, obesity, and iron and ROS homeostasis (6).

Enhanced expression of NAF-1 or mNT is associated with different cancers, including breast (10, 11, 14), prostate (15), gastric (16), cervical (17), liver (18), and laryngeal cancer (19). Silencing of mNT or NAF-1 expression in breast (10, 11) or gastric (16) cancer cells significantly inhibited cellular proliferation and tumorigenicity, whereas overexpression of mNT in breast (14) or NAF-1 in gastric (16) cancer cells significantly enhanced cellular proliferation. Moreover, patients with gastric and liver cancer with high NAF-1 expression displayed a shorter survival and higher recurrence rate compared with patients with low NAF-1 expression (16, 18). Taken together, these studies point to a potential key role for the NEET proteins NAF-1 and mNT in promoting the proliferation of different epithelial cancers. Nevertheless, it is unknown what role the NEET’s 2Fe-2S clusters play in promoting cancer cell proliferation and tumorigenicity.

Here we report that the lability of the NAF-1 cluster plays a key role in promoting rapid tumor growth through enhancing cellular resistance to oxidative stress. We further demonstrate that a drug that increases the stability of the NAF-1 cluster [pioglitazone (PGZ)] could be used to target cancer cells with high levels of NAF-1 overexpression.

Results

NAF-1 Overexpression Results in a Dramatic Augmentation in Xenograft Tumor Growth and Proliferation.

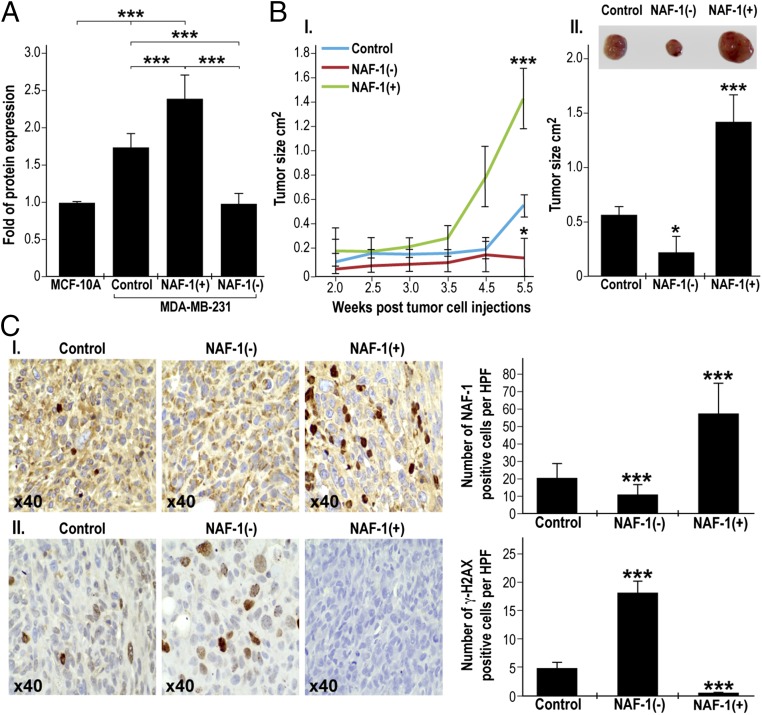

Enhanced expression of the 2Fe-2S protein NAF-1 is associated with the onset and progression of multiple cancer types (10, 11, 14–19). To determine whether elevated NAF-1 levels play a direct role in tumor development, we stably overexpressed NAF-1 in MDA-MB-231 cells [NAF-1(+)] and generated xenograft tumors in nude mice. As controls we generated xenograft tumors using MDA-MB-231 cells having native levels of NAF-1 (control), as well as MDA-MB-231 cells in which NAF-1 expression was suppressed via shRNA [NAF-1(−)] (10, 11). As shown in Fig. 1A, the endogenous expression of NAF-1 in control MDA-MB-231 cells is significantly higher compared with that of nonmalignant epithelial breast cells (MCF-10A), and overexpression of NAF-1 in MDA-MB-231 cells [NAF-1(+)] resulted in a further elevation of NAF-1 expression. Remarkably, xenograft tumors that developed from NAF-1(+) MDA-MB-231 cells were significantly larger and developed significantly faster than xenograft tumors that developed from control or NAF-1(−) cells (Fig. 1B). In agreement with their increased aggressiveness, NAF-1(+) tumors displayed elevated levels of cellular markers for cancer cell proliferation, including nuclear membrane and rough ER deformations and Golgi accumulation (Fig. S1). Furthermore, they contained fewer cells with elevated levels of the DNA damage marker protein γH2AX (Fig. 1C), suggesting that the enhanced expression of NAF-1 protected cancer cells from nuclear DNA damage. These results demonstrate that overexpression of the 2Fe-2S NAF-1 protein is directly involved in promoting the rapid growth and aggressiveness of breast cancer tumors.

Fig. 1.

Enhanced expression of NAF-1 in human MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells is associated with significant xenograft tumor growth in vivo. (A) Expression of NAF-1 in in noncancerous epithelial breast cells (MCF-10A), MDA-MB-231 (control), NAF-1(+), and NAF-1(−) measured as described in ref. 11. (B, I) Mean plot of tumor size (cm2) change over time comparing control, NAF-1(+), and NAF-1(−) xenograft tumors. Average ± SD tumor size for each time point is presented. (II) Bar graph showing xenograft tumor size at 5.5 wk following tumor injection. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, n = 30 (10 in each group). (C, I) IHC for NAF-1 showing increase in the number of NAF-1+ cells in NAF-1(+) compared with control and NAF-1(−) tumors. (II) IHC for γH2AX, a marker for cellular senescence, showing a decrease in the number of γH2AX+ cells in NAF-1(+) compared with control and NAF-1(−) tumors. (Left) Representative sections 40×. (Right) Quantification of positive cells. Cells were counted in 10 high-power fields (40×) for each section obtained from five mice in each group and average ± SD counts are presented. ***P < 0.001.

Fig. S1.

Accumulation of cellular markers for enhanced metabolic activity in cells from control, NAF-1(+), and NAF-1 (−) xenograft tumors. (A–C) Representative TEM images from MDA-MB-231 tumor xenografts of control (Left), NAF-1(+) (Center), and NAF-1(−) (Right) are shown side by side with quantitative analysis graphs (Far Right) of nuclear membrane deformation (A), rough endoplasmatic reticulum (RER) deformation (B), and the accumulation of Golgi per cell (C). ***P < 0.001 (n = 20 different sections).

Enhanced Expression of NAF-1 Is Associated with Enhanced Metabolic Activity of Breast Cancer Cells and Enhanced Tolerance to Oxidative Stress.

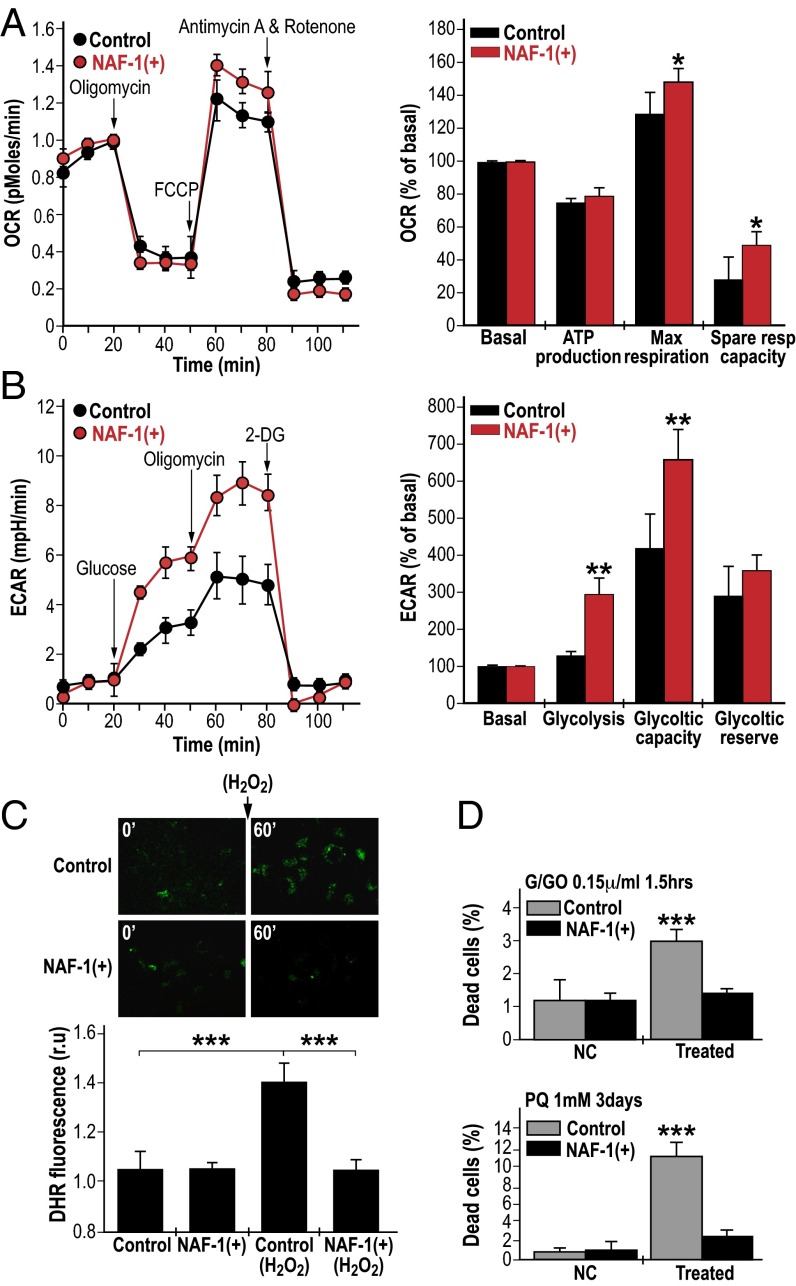

Enhanced proliferation of cancer cells is associated with elevated metabolic activity, metabolic stress, and enhanced ROS production (4, 20). Overexpression of NAF-1 in cancer cells could promote cellular proliferation by alleviating metabolic stress, as well as preventing metabolic stress-derived ROS accumulation. To determine whether enhanced NAF-1 expression promoted cellular proliferation via reducing metabolic stress we tested respiration, glycolysis, and ROS accumulation in NAF-1–overexpressing cells. Overexpression of NAF-1 resulted in enhanced respiration and glycolytic activity, supporting the possible production of excess metabolic ROS (Fig. 2 A and B) (4, 20–23). Remarkably, we were unable, however, to detect elevated levels of ROS in NAF-1(+) cells, compared with controls (Fig. 2C). Moreover, NAF-1(+) cells were able to detoxify H2O2 more efficiently than control cells (Fig. 2C) and had a higher survival rate compared with control cells when challenged with H2O2 or superoxide (Fig. 2D), suggesting that they could contain elevated levels of ROS detoxifying mechanisms. Similar resistance to oxidative stress was observed in MCF-7, a different human epithelial breast cancer cell line, overexpressing NAF-1 (Fig. S2). Moreover, the application of the iron chelator deferiprone (DFP) or the antioxidant N-acetyl cysteine (NAC) had a protective effect similar to that of NAF-1 overexpression on control cancer cells challenged with oxidative stress (Fig. S3), further demonstrating that an enhanced potential for ROS scavenging could be the basis of NAF-1 function in cancer cells. Because oxidative stress in cells is associated with mTOR inactivation leading to suppressed cell proliferation, as well as HIF-1α stabilization leading to the induction of ROS-scavenging mechanisms (24–26), we measured the expression of HIF-1α and the phosphorylation state of two mTOR target proteins (Fig. S4). Our results indicate that overexpression of NAF-1 caused HIF-1α stabilization and that mTOR was not inactivated in NAF-1(+) cells.

Fig. 2.

Enhanced expression of NAF-1 is associated with enhanced metabolic activity and oxidative stress resistance of cancer cells. (A) Oxygen consumption rates (OCR) (Left) and calculated spare respiratory activity values (Right) of control and NAF-1(+) cells showing enhanced respiratory activity of NAF-1(+) cells. (B) Extracellular acidification rates (ECAR) (Right) and calculated glycolytic capacity of control and NAF-1(+) cells showing enhanced glycolytic activity of NAF-1(+) cells. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. (C) Detoxification of ROS by NAF-1(+) cells. (C, Upper) Semiconfocal Images of control and NAF-1(+) cells at 0 min and 60 min following preincubation with Dihydrorhodamine 123; 2-(3,6-Diamino-9H-xanthene-9-yl)-benzoic acid methyl ester (DHR) for 10 min in the presence or absence of H2O2 (50 µM). (Lower) Quantification of DHR mean fluorescence at 60 min in the presence or absence of H2O2 (50 µM). ***P < 0.001. (D) Quantitative analysis of cell death in control and NAF-1(+) cells treated or not treated with G/GO (10 mM/0.15 units/mL) or paraquat (1 mM). ***P < 0.001.

Fig. S2.

Detoxification of ROS by MCF-7-NAF-1(+) cells. (A) Semiconfocal images of control and NAF-1(+) MCF-7 cells at 0 min and 60 min following preincubation with DHR for 10 min in the presence or absence of hydrogen peroxide (50 µM). (Magnification: 600×.) (B) Bar graphs showing quantification of DHR mean fluorescence at 60 min in the presence or absence of hydrogen peroxide (50 µM). (C) Bar graphs showing the quantitative analysis of cell death in control and NAF-1(+) MCF-7 cells treated with G/GO (10 mM/0.15 µnits/mL). ***P < 0.0001.

Fig. S3.

Survival of control and NAF-1(+) MDA-MB-231 cells treated with G/GO in the presence or absence of DFP or NAC. Bar graphs show the quantitative analysis of cell death in control and NAF-1(+) cells treated or not treated (NC) with G/GO (10 mM/0.15 µnits/mL) in the presence or absence of DFP (100 μM) or NAC (1 mM). **P < 0.01.

Fig. S4.

Overexpression of NAF-1 resulted in HIF-1α stabilization and maintenance of high basal levels of pS6 and p-4EBP1 phosphorylation. Protein blot analysis (Top) and quantification (Bottom) of control and NAF-1(+) cells measure the protein levels of HIF-1α and phosphorylated pS6. β-Actin was used as a loading control. Quantification of protein expression was performed per total protein for three different experiments. **P < 0.01.

Enhanced Expression of NAF-1 Is Associated with Elevated Expression of Transcripts and Proteins Involved in ROS Detoxification.

To determine whether enhanced NAF-1 expression is associated with enhanced expression of proteins and transcripts involved in ROS detoxification, we performed proteomics analysis of xenograft tumors overexpressing NAF-1. In addition, we conducted meta-analysis of transcriptomics data from a collection of triple-negative breast cancer cell lines (Fig. 3 and Figs. S5 and S6). Our proteomic analysis identified 359 proteins significantly up-regulated and 287 proteins significantly down-regulated in NAF-1(+) tumors (for complete details, see SI Materials and Methods, Fig. 3A, Fig. S5, and Datasets S1 and S2). Gene Ontology and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway annotations of the proteins enriched in NAF-1(+) tumors pointed to enhanced ROS detoxification and pentose phosphate pathways (supply of NADPH for ROS removal), coupled with reduced oxidative phosphorylation, TCA cycle, and fatty acid oxidation (potential sources of ROS) (Fig. S5 and Dataset S3). The level of several key proteins involved in ROS detoxification was found to be up-regulated in NAF-1(+) tumors (Fig. 3A). These included superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1), glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4), glutathione synthase (GSS), sulfiredoxin 1 (SRXN1), copper chaperone for SOD (CCS), glutaredoxin-1, and ferritin light and heavy chain proteins (Dataset S2). We further confirmed by immunohistochemistry (IHC) that ferritin (FTH-1) is up-regulated in NAF-1(+) tumors (Fig. 3B). Ferritin could play a key role in ROS detoxification via sequestering of free iron that could potentially lead to the formation of hydroxyl radicals. We further analyzed transcriptomics data obtained from 21 different triple-negative (TN) human epithelial breast cancer cell lines (27). As shown in Fig. 3C, the expression of NAF-1 was positively correlated with that of SRXN1, GPX1, GSS, NAD(P)H dehydrogenase quinone 1 (NQO1), peroxiredoxin 1 (PRX1), and thioredoxin reductase 1 (TXNRD1), all involved in ROS metabolism and detoxification. NAF-1 accumulation was also associated with the enhanced accumulation of transcripts encoding cell cycle control proteins (Fig. S6). The findings presented in Fig. 3, Fig. S5, and Dataset S1 suggest that NAF-1 overexpression is associated with resistance of cells to oxidative stress, a possible mechanism that could promote rapid tumor cell growth (21–23).

Fig. 3.

NAF-1 overexpression is associated with the up-regulation of ROS-related proteins in breast cancer clinical samples and xenografts. (A) Expression intensities for selected ROS-related proteins in NAF-1(+) and control tumors using proteomic analysis on tumor control and NAF-1(+) xenografts. LFQ, label-free quantification. Proteomics analysis is described in SI Materials and Methods. *P < 0.02, **P < 0.001, ***P < 0.0001, n = 4 in each group. (B) IHC for ferritin heavy polypeptide 1 (FTH-1). (Left) Representative sections, 40×. (Right) Ferritin+ cells were counted in 10 high-power fields (×40) for each section obtained from 10 mice in each group and average ±SD counts are presented. ***P < 0.001. (C) Correlation network for NAF-1 and different transcripts that positively (purple) or negatively (green) correlate with NAF-1 expression in transcriptomic data from 21 different human TN breast cancer cell lines (27). All correlations were filtered with a cutoff of ±0.40. Black edges, positive correlation; red edges, negative correlation. The thickness of the edges is related to the absolute value of the correlation.

Fig. S5.

Proteomic analysis of xenograft tumors with enhanced NAF-1 expression. (A) Hierarchical clustering of significantly up- and down-regulated proteins in NAF-1(+) compared with control tumors. (B) Protein interaction networks of proteins belonging to enriched processes in NAF-1(+) compared with control tumors. Node size represents t-test difference.

Fig. S6.

Expression correlation plots in transcriptomic data from 21 different human TN breast cancer cell lines between NAF-1 (CISD2) and (A) SRXN1, GPX1, GSS, TXNRD1, PRDX1, and NQO1 and (B) CDC23, CCNA2, and CDC14A. Transcriptomics data were obtained from ref. 32.

A Mutation That Stabilizes the NAF-1 2Fe-2S Clusters (H114C) Abolishes Its Tumor-Promoting and Oxidative Stress Protection Functions in Cancer Cells.

To determine whether the function of NAF-1 in promoting tumor growth (Fig. 1) is dependent on the function of the NAF-1 clusters, we overexpressed in MDA-MB-231 cells a mutated form of NAF-1 in which the 3Cys-1His cluster coordination structure was changed into a 4-Cys cluster (H114C) (Fig. 4 A, I). The NAF-1(H114C) mutant protein is 25-fold more stable and has a reducing potential (Em) that is ∼300 mV more negative than that of wild-type NAF-1 (28). In addition, the NAF-1(H114C) mutant was unable to donate its cluster to an acceptor protein (28). The overexpression of H114C in cancer cells is expected to completely or partially replace the native NAF-1 protein with the H114C inactive variant and/or inhibit NAF-1 function via the formation of inactive NAF-1/H114C dimers (i.e., a dominant-negative effect) (6). As shown in Fig. 4 A, II, the H114C protein was stable in NAF-1(H114C) MDA-MB-231 cancer cells and accumulated to the same level as the overexpressed wild-type NAF-1 in NAF-1(+) cells. Remarkably, xenograft tumors that developed from NAF-1(H114C) cells were significantly smaller than those developed from control or NAF-1(+) cells (Fig. 4 B and C). This finding clearly indicates that the lability of the 2Fe-2S NAF-1 cluster is critical for its tumor-promoting function. NAF-1 was previously shown to regulate the levels of mitochondrial iron and ROS in cells (10, 11). To determine whether the lability of the NAF-1 cluster is required for this function in cancer cells we measured mitochondrial iron and ROS in NAF-1(H114C) cells. Compared with control or NAF-1(+) cells, the mitochondria of NAF-1(H114C) cells accumulated significant levels of iron and ROS (Fig. 4D). To determine whether the lability of the NAF-1 cluster is also required for enhancing the ROS detoxification capacity of cells, we challenged NAF-1(H114C) cells with H2O2. In contrast to untreated control or NAF-1(+) cells, untreated NAF-1(H114C) cells accumulated significant levels of ROS (Fig. 4D). Moreover, whereas NAF-1(+) cells were able to detoxify H2O2 that was added to their culture, control and NAF-1(H114C) cells were unable to do so (Fig. 4D). These findings provided an important link between mitochondrial iron accumulation, the function of NAF-1 in mediating Fe-S cluster transfer reactions in cells, and the overall resistance of cells to oxidative stress. In addition, they strongly support a role for the labile 2Fe-2S cluster of NAF-1 in alleviating ROS stress in cancer cells.

Fig. 4.

Overexpression of a NAF-1 mutant NAF-1(H114C) with a single amino acid mutation exchanging 3Cys-1His to a 4Cys cluster resulted in a dramatic decrease in tumor size in vivo, accompanied by reduced tolerance to oxidative stress. (A, I) Structure of the NAF-1 3Cys-1His cluster vs. the NAF-1(H114C) mutant with a 4Cys cluster. (II) Expression of NAF-1 in MDA-MB-231 (control), NAF-1(+), and NAF-1(H114C) cells measured as described in ref. 11. (B) Mean plot of tumor size (cm2) change over time comparing control, NAF-1(+), and NAF-1(H114C) xenograft tumors. Average ± SD tumor size for each time point is presented. (C) Bar graph showing xenograft tumor size at 5 wk following tumor injection. ***P < 0.001, n = 30 (10 in each group). (D) Detoxification of ROS by control, NAF-1(+), and NAF-1(H114C) cells. (Upper) Semiconfocal images of control, NAF-1(+), and NAF-1(H114C) cells at 0 min and 60 min following preincubation with DHR for 10 min in the presence or absence of H2O2 (50 µM). (Magnification: 600×.) (Lower) Quantification of DHR mean fluorescence at 60 min in the presence or absence of H2O2 (50 µM). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Treatment with PGZ, a Drug That Stabilizes the Native 3Cys-1His 2Fe-2S Cluster of NAF-1, Inhibits the Function of NAF-1 in Cancer Cells and Results in the Overaccumulation of Mitochondrial Iron and ROS.

The thiazolidinedione (TZD) class of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR-γ) ligand drugs is known for its ability to induce adipocyte differentiation, to increase insulin sensitivity, and to have anticancer properties (29, 30). We previously showed that PGZ, a TZD drug, inhibits NAF-1’s ability to transfer its cluster to apo-acceptor proteins (31). To test whether stabilizing the NAF-1 cluster via treatment with TZD has an effect on cancer cells similar to that of overexpressing the cluster-stable NAF-1(H114C) mutant, we treated control, NAF-1(+), and NAF-1(H114C) cells with 100 µM PGZ overnight. As shown in Fig. 5 A, I, treatment of control or NAF-1(+) cells with PGZ resulted in the accumulation of mitochondrial iron to levels similar to that observed for untreated NAF-1(H114C) cells. In contrast, no further increase in mitochondrial iron could be obtained by treatment of NAF-1(H114C) cells with PGZ (Fig. 5 A, I). Treatment of NAF-1(+) cells with PGZ also resulted in a significant increase in mitochondrial ROS levels (Fig. 5 A, II). In contrast, treatment of control cells with PGZ did not alter the level of mitochondrial ROS. In addition, no further increase in mitochondrial ROS could be obtained by treatment of NAF-1(H114C) cells with PGZ (Fig. 5 A, II). These findings suggested that in contrast to control cells that have a native level of NAF-1 protein, NAF-1(+) cells that overexpress NAF-1 are more sensitive to PGZ. Furthermore, cells that overexpress the NAF-1(H114C) protein and already have high levels of mitochondrial iron and ROS are insensitive to treatment with PGZ. To further study the binding of PGZ to NAF-1 we used our in-house molecular docking method iFitDock (32) to dissect their interaction. In our model, PGZ binds to NAF-1 (PDB ID code 4OO7) with a binding energy of −42 kJ/mol. PGZ binding is accompanied by both hydrophobic interactions and the formation of four hydrogen bonds between PGZ and residues Y98, K81, H114, and N115 (Fig. 5B). Thus, our model predicts that PGZ binds to NAF-1 in the vicinity of its clusters, shielding His114 and preventing it from undergoing protonation that would cause cluster destabilization. The findings presented in Fig. 5 highlight a potential use of drugs that stabilize the clusters of NEET proteins in the treatment of cancers with high expression level of NAF-1.

Fig. 5.

Treatment with PGZ, a drug that stabilizes the 3Cys-1His clusters of NAF-1, inhibits the function of NAF-1 in cancer cells and results in the overaccumulation of mitochondrial iron and ROS. (A) Accumulation of mitochondrial iron measured with rhodamine B-[(1,10-phenanthrolin-5-yl aminocarbonyl] benzyl ester (RPA) (A, I) and mitochondrial ROS measured with mitoSOX (Mitochondrial Superoxide Indicator Red) (II) in control, NAF-1(+), and NAF-1(H114C) MDA-MB-231 cells treated overnight with PGZ (100 µM). The bar graph represents mean fluorescence values as relative unit (r.u.) of more than 10 cells per field, calculated for the initial images and images after 1 h and normalized to the initial fluorescence (f/f0) *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, n = 30 (10 in each group). (B) The predicated binding mode of PGZ to NAF-1. PGZ binds in the vicinity of the 2Fe-2S cluster of NAF-1 (binding free energy of −42 kJ/mol). The pink stick-ball model is the PGZ compound. Hydrogen bonds between PGZ and NAF-1 are shown as red dashed lines. The list of NAF-1 amino acids that interact with PGZ by π–π interactions or hydrogen bonding is provided in the table on the left side of the structure.

SI Materials and Methods

Sample Preparation for Proteomic Analysis.

Four different xenografts of either control or overexpressed NAF-1 were analyzed. Xenograft paraffin blocks were cut into 10-μm-thick sections, using a microtome, and were deparaffinized using xylene and an ethanol/water gradient. The tissue was scraped into a lysis buffer [50% (vol/vol) 2-2-2 trifluoroethanol in 25 mM ammonium bicarbonate] and sonicated. Proteins were reduced with 5 mM DTT and alkylated with 15 mM IAA (Sigma-Aldrich), followed by overnight digestion with LysC (Wako chemicals; 1:100 protein concentration ratio) and trypsin (Promega; 1:50). Resulting peptides were acidified with TFA and fractionated using stage-tip–based SCX microcolumns. Peptides were separated by nano-ultra HPLC coupled on line to a Q-Exactive Plus mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific), using a 140-min water–acetonitrile gradient. Mass spectra were acquired in a data-dependent manner with the top-10 precursor m/z values from each MS scan fragmented by higher-energy collisional dissociation.

Proteomic Data Analysis.

MS raw files were analyzed by MaxQuant (version 1.5.3.5). MS/MS spectra were searched against the human Uniprot database (November 2014) by the Andromeda search engine. False-discovery rate (FDR) of 0.01 was used on both the peptide and protein levels and determined by a decoy database. Protein intensities were quantified using a label-free approach (34). Bioinformatics and statistical analyses of proteomic data were performed with the Perseus software (35) on proteins that were present in >75% of the samples. Welch’s t tests for statistical significance were performed with a permutation-based FDR correction threshold of 0.05. Fisher’s exact tests for annotation enrichment were performed with FDR threshold of 0.02 against the human proteome. Welch’s t tests for statistical significance were performed as described in ref. 36. Protein interaction network was constructed using STRING database (string-db.org).

Supplementary Computational Calculations.

Computational calculations were performed as previously described in ref. 33. To determine the binding mode of PGZ to NAF-1, PGZ was docked on the identified druggable binding site by using our in-house molecular docking tool named iFitDock. The structure of NAF-1 (PDB ID code 4OO7) was prepared with the Protein Preparation Wizard (37) integrated in a multiple-purpose molecular modeling environment called Maestro (https://www.schrodinger.com/maestro) with default settings, deleting water molecules, adding hydrogens, and loading charges with AMBER Force Field. A large grid box with the size of 40 × 20 × 25 Å3 was carefully designed to cover the whole identified druggable binding site on NAF-1 and a scoring grid of NAF-1 for docking was generated by using DOCK 6.5 (38). The initial 3D coordination of PGZ was built by Chem3D 14.0 (39) and minimized using the MM2 force field available in Chem3D with standard setup. The Gasteiger–Marsili method was used to assign partial atomic charges to PGZ. The molecular-mechanic–generalized born solvent accessible (MM-GBSA) method available in iFitDock was used to estimate the binding free energy for the predicted binding mode of PGZ to NAF-1. The structure of NAF-1 was taken as rigid and the parameters were set as default in docking simulations. As a result, the binding mode with the lowest binding free energy (−42 kJ/mol) was selected as the predicted binding structure of PGZ to NAF-1.

Discussion

Maintaining the biogenesis of Fe-S clusters was shown to be important for cancer cell proliferation, suggesting that Fe-S–containing proteins could play an important role in cancer cell metabolism (1–5). Here, we identified the 2Fe-2S protein NAF-1 as a key protein that promotes tumorigenicity when overexpressed in cancer cells (Fig. 1). Thus, overexpression of NAF-1 in xenograft breast cancer tumors resulted in a dramatic enhancement in tumor size and aggressiveness in vivo, as well as enhanced the tolerance of cancer cells to oxidative stress (Figs. 1–3). Remarkably, overexpression of a NAF-1 mutant, with a single amino acid mutation, NAF-1(H114C), that stabilizes its 2Fe-2S cluster 25-fold over that of the native NAF-1 cluster in cancer cells, resulted in a dramatic decrease in tumor size in vivo, accompanied by enhanced mitochondrial iron and ROS accumulation and reduced tolerance to oxidative stress (Figs. 4 and 5). Furthermore, treatment of NAF-1(+) cells with PGZ, a drug that stabilizes the 3Cys-1His cluster of NAF-1, resulted in a similar phenotype to that of overexpressing the stable mutant of NAF-1 in cells [NAF-1(H114C)] (Fig. 5). Taken together, these findings point to a key role for the 3Cys-1His cluster coordination structure of NAF-1 in promoting rapid tumor growth, probably through enhanced cellular resistance to oxidative stress.

Proliferating breast cancer cells are thought to accumulate high levels of iron and ROS in their mitochondria, up to levels that could potentially limit their growth and proliferation (23). Our findings that overexpression of the NAF-1(H114C) protein failed to attenuate the mitochondrial levels of iron and ROS and resulted in suppressed tumor growth (to below that of normal cancer cells; Fig. 4) provide direct evidence for a key role for the NAF-1 2Fe-2S cluster in these functions. NAF-1 could therefore be preventing the buildup of labile iron in mitochondria and its adverse consequences of enhanced ROS formation in proliferating breast cancer cells, via reactions that are mediated by NAF-1’s 2Fe-2S cluster. The accumulation of labile iron in the mitochondria could therefore be rate limiting for breast cancer cell proliferation, and the function of the labile 2Fe-2S cluster of the overexpressed NAF-1 protein could be key to inducing a state of enhanced tolerance to oxidative stress in cancer cells and tumors.

Alterations in NAF-1 cluster lability by PGZ or the H114C mutation resulted in the overaccumulation of iron and ROS in mitochondria of cancer cells (Figs. 4 and 5). These findings support our previous report that NAF-1 could be one of the cellular targets of a mitocan that affects its cluster stability and causes an increase in mitochondrial iron and ROS accumulation (33). Taken together, our findings suggest that any drastic change in the lability of the NAF-1 cluster would impair its function in maintaining the levels of iron and ROS in mitochondria under control. Altering NAF-1 cluster lability via different drugs could therefore be used to treat different cancers that depend on NAF-1 overexpression for their proliferation (10, 11, 14–19).

From the mechanistic standpoint, we demonstrate that at least two different components are required for NAF-1 to promote breast cancer tumorigenicity: a high level of NAF-1 protein expression and a unique cluster coordination structure that allows cluster lability. Only together do these two components create a cellular environment that promotes cancer cell tumorigenicity and enhances tolerance to oxidative stress. The high levels of NAF-1 protein coupled with the lability of its cluster achieve therefore a cellular threshold that enables cancer cells to maintain a high energetic state without the overaccumulation of iron and ROS in their mitochondria. In addition, they promote ROS resistance through the stabilization of HIF-1α and the accumulation of many antioxidative proteins and transcripts (Fig. 3 and Figs. S4–S6). Our findings establish a key role for NAF-1 overexpression in promoting the tumorigenicity of breast cancer cells (Fig. 1). Furthermore, they provide a mechanistic foundation for the role of NAF-1 overexpression in multiple cancer types, including breast (10, 11), prostate (15), gastric (16), cervical (17), liver (18), and laryngeal cancers (19).

Conclusion

Elevated expression of NAF-1 is associated with the progression of multiple cancer types. Here we show that NAF-1 overexpression in xenograft tumors results in a dramatic augmentation in tumor size and aggressiveness and that at least two different components are required for NAF-1 to promote breast cancer tumorigenicity: high levels of NAF-1 protein expression and a unique cluster coordination structure that conveys cluster lability. We propose that together these two components protect cancer cells from oxidative stress by preventing the buildup of labile iron and ROS in mitochondria. Drugs that alter NAF-1 cluster stability and/or NAF-1 protein level could therefore be used to treat multiple cancers that express high levels of NAF-1.

Materials and Methods

Animal Studies.

Animal experiments were performed in compliance with the Hebrew University Authority for biological and biomedical models (NS-13-13911-4). MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells (2.5 × 105) with normal NAF-1 (control), suppressed NAF-1 [shRNA; NAF-1(−)], or overexpressed NAF-1 [NAF-1(+) or NAF-1(H114C)] were injected s.c. into female athymic nude (FOXN1NU) 5- to 6-wk-old mice. Mouse weight and tumor size were measured twice weekly throughout the experiment.

Cell Culture Analysis and Drug Treatment.

MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells were grown as described in ref. 10. Plasmid for suppressing NAF-1 expression [shRNA; NAF-1(−)] (10) was pGFP-RS vector, and plasmid for overexpressing NAF-1 [NAF-1(+) or NAF-1(H114C)] was pEGFP-N1 vector. GenJuice (EMD Millipore) was used for transfection (10). Stable cell lines were obtained by FACS sorting, and protein expression was confirmed by protein blots (10, 11). Fluorescence microscopy was performed as described in refs. 10 and 11.

IHC and Transmission Electron Microscopy.

s.c. tumors were recovered from necropsy, measured for weight and size, and fixed for IHC and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and analyzed as described in refs. 10 and 11. The histological examination was performed by a pathologist (E.P.). Anti-CISD2 (NAF-1; HPA015914; Sigma) and antiphospho-Histone H2A.X (Ser139; clone JBW301; Merck) were used for IHC as described in ref. 11.

Cell Viability, Metabolic Activity, and Growth Measurements.

Alamar-blue (Invitrogen) was used to determine cell viability, and a Moxi Z cell counter (ORFLO Technologies) was used to measure cell growth (10). Paraquat (1 mM; 0–3 d) and glucose/glucose oxidase (G/GO; 10 mM/0.15 units/mL; 0–2 h) were used to induce oxidative stress. Oxygen consumption and extracellular acidification rates were measured using a Seahorse XF24 analyzer (Seahorse Bioscience) as described in ref. 10.

Meta-Analysis of Transcriptomics Data from 21 TN (ER-, PR-, Her2-) Human Breast Cancer Cell Lines.

Transcriptomics data for HCC70, HCC1143, HCC1187, BT20, SUM185PE, SUM1315MO2, MCF12A, MCF10a, MCF10F, MDA-MB-157, MDA-MB-231, HS578T, HCC1806, HCC3153, SUM149PT, HCC38, HCC2185, BT549, HCC1937, SUM159PT, and HCC1395 were obtained from ref. 27. Pearson correlation was calculated between the expression levels of NAF-1 and the expression levels of different transcripts encoding ROS detoxification [antioxidant activity: Gene Ontology (GO): 0016209] or cell cycle regulation (cell cycle: GO: 0007049). A correlation network was constructed with a cutoff of ±0.4 and visualized with Cytoscape (www.cytoscape.org/). The following criterion was used: Two randomly sampled datasets (from Gaussian distribution) have no more than 4% chance of having Pearson correlation above the cutoff value.

Proteomic Analysis.

Paraffin blocks from four different xenograft tumors of either control or overexpressed NAF-1 were cut and subjected to proteomics and statistical analysis as described in SI Materials and Methods.

Computational Calculations.

The druggable binding site on NAF-1 was identified by a four-step computational scheme in our previous work (33). Based on this finding, the binding of PGZ to NAF-1 was studied by our in-house docking molecular tool iFitDock (details in SI Materials and Methods).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Israel Science Foundation Grant 865/13 (to R.N.); the University of North Texas College of Arts and Sciences (R.M.); and the Israel Cancer Research Fund (T.G.). Work at the Center for Theoretical Biological Physics is sponsored by the National Science Foundation (Grants PHY-1427654) and by the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT) (R1110). M.L. is supported by a training fellowship from the Keck Center for Interdisciplinary Bioscience Training of the Gulf Coast Consortia (CPRIT Grant RP140113); F.B. was partially supported by the Welch Foundation (Grant C-1792); and P.A.J. is supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM101467.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1612736113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Gee HE, Ivan C, Calin GA, Ivan M. HypoxamiRs and cancer: From biology to targeted therapy. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;21(8):1220–1238. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thierbach R, et al. Targeted disruption of hepatic frataxin expression causes impaired mitochondrial function, decreased life span and tumor growth in mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14(24):3857–3864. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Funauchi Y, et al. Regulation of iron homeostasis by the p53-ISCU pathway. Sci Rep. 2015;5:16497. doi: 10.1038/srep16497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sullivan LB, Chandel NS. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species and cancer. Cancer Metab. 2014;2:17. doi: 10.1186/2049-3002-2-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gari K, et al. MMS19 links cytoplasmic iron-sulfur cluster assembly to DNA metabolism. Science. 2012;337(6091):243–245. doi: 10.1126/science.1219664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tamir S, et al. Structure-function analysis of NEET proteins uncovers their role as key regulators of iron and ROS homeostasis in health and disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1853(6):1294–1315. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Du X, et al. NAF-1 antagonizes starvation-induced autophagy through AMPK signaling pathway in cardiomyocytes. Cell Biol Int. 2015;39(7):816–823. doi: 10.1002/cbin.10453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vento MT, et al. Praf2 is a novel Bcl-xL/Bcl-2 interacting protein with the ability to modulate survival of cancer cells. PLoS One. 2010;5(12):e15636. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang CH, Tsai TF, Wei YH. Role of mitochondrial dysfunction and dysregulation of Ca(2+) homeostasis in insulin insensitivity of mammalian cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2015;1350:66–76. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sohn YS, et al. NAF-1 and mitoNEET are central to human breast cancer proliferation by maintaining mitochondrial homeostasis and promoting tumor growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(36):14676–14681. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1313198110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holt SH, et al. Activation of apoptosis in NAF-1-deficient human epithelial breast cancer cells. J Cell Sci. 2016;129(1):155–165. doi: 10.1242/jcs.178293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang NC, et al. Bcl-2-associated autophagy regulator Naf-1 required for maintenance of skeletal muscle. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21(10):2277–2287. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu CY, et al. A persistent level of Cisd2 extends healthy lifespan and delays aging in mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21(18):3956–3968. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salem AF, Whitaker-Menezes D, Howell A, Sotgia F, Lisanti MP. Mitochondrial biogenesis in epithelial cancer cells promotes breast cancer tumor growth and confers autophagy resistance. Cell Cycle. 2012;11(22):4174–4180. doi: 10.4161/cc.22376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ge YZ, et al. Pathway analysis of genome-wide association study on serum prostate-specific antigen levels. Gene. 2014;551(1):86–91. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2014.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang L, et al. Overexpressed CISD2 has prognostic value in human gastric cancer and promotes gastric cancer cell proliferation and tumorigenesis via AKT signaling pathway. Oncotarget. 2016;7(4):3791–3805. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu L, et al. CISD2 expression is a novel marker correlating with pelvic lymph node metastasis and prognosis in patients with early-stage cervical cancer. Med Oncol. 2014;31(9):183. doi: 10.1007/s12032-014-0183-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen B, et al. CISD2 associated with proliferation indicates negative prognosis in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8(10):13725–13738. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang L, et al. A novel prognostic score model incorporating CDGSH Iron Sulfur Domain2 (CISD2) predicts risk of disease progression in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2016;7(16):22720–22732. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poillet-Perez L, Despouy G, Delage-Mourroux R, Boyer-Guittaut M. Interplay between ROS and autophagy in cancer cells, from tumor initiation to cancer therapy. Redox Biol. 2015;4:184–192. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2014.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tong L, Chuang CC, Wu S, Zuo L. Reactive oxygen species in redox cancer therapy. Cancer Lett. 2015;367(1):18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manda G, et al. The redox biology network in cancer pathophysiology and therapeutics. Redox Biol. 2015;5:347–357. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2015.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Torti SV, Torti FM. Iron and cancer: More ore to be mined. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13(5):342–355. doi: 10.1038/nrc3495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu SB, Wu YT, Wu TP, Wei YH. Role of AMPK-mediated adaptive responses in human cells with mitochondrial dysfunction to oxidative stress. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1840(4):1331–1344. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sofer A, Lei K, Johannessen CM, Ellisen LW. Regulation of mTOR and cell growth in response to energy stress by REDD1. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25(14):5834–5845. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.14.5834-5845.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Movafagh S, Crook S, Vo K. Regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1a by reactive oxygen species: New developments in an old debate. J Cell Biochem. 2015;116(5):696–703. doi: 10.1002/jcb.25074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Costello JC, et al. NCI DREAM Community A community effort to assess and improve drug sensitivity prediction algorithms. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32(12):1202–1212. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tamir S, et al. A point mutation in the [2Fe-2S] cluster binding region of the NAF-1 protein (H114C) dramatically hinders the cluster donor properties. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2014;70(Pt 6):1572–1578. doi: 10.1107/S1399004714005458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nadarajan K, Balaram P, Khoo BY. MK886 inhibits the pioglitazone-induced anti-invasion of MDA-MB-231 cells is associated with PPARα/γ, FGF4 and 5LOX. Cytotechnology. January 11, 2016 doi: 10.1007/s10616-015-9930-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kole L, Sarkar M, Deb A, Giri B. Pioglitazone, an anti-diabetic drug requires sustained MAPK activation for its anti-tumor activity in MCF7 breast cancer cells, independent of PPAR-γ pathway. Pharmacol Rep. 2016;68(1):144–154. doi: 10.1016/j.pharep.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tamir S, et al. Nutrient-deprivation autophagy factor-1 (NAF-1): Biochemical properties of a novel cellular target for anti-diabetic drugs. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e61202. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bai F, et al. Free energy landscape for the binding process of Huperzine A to acetylcholinesterase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(11):4273–4278. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1301814110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bai F, et al. The Fe-S cluster-containing NEET proteins mitoNEET and NAF-1 as chemotherapeutic targets in breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(12):3698–3703. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1502960112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cox J, et al. Accurate proteome-wide label-free quantification by delayed normalization and maximal peptide ratio extraction, termed MaxLFQ. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2014;13(9):2513–2526. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M113.031591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tyanova S, et al. The Perseus computational platform for comprehensive analysis of (prote)omics data. Nat Methods. 2016;13(9):731–740. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pozniak Y, et al. System-wide clinical proteomics of breast cancer reveals global remodeling of tissue homeostasis. Cell Syst. 2016;2(3):172–184. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2016.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sastry GM, Adzhigirey M, Day T, Annabhimoju R, Sherman W. Protein and ligand preparation: Parameters, protocols, and influence on virtual screening enrichments. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 2013;27(3):221–234. doi: 10.1007/s10822-013-9644-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lang PT, et al. DOCK 6: Combining techniques to model RNA-small molecule complexes. RNA. 2009;15(6):1219–1230. doi: 10.1261/rna.1563609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mills N. ChemDraw Ultra 10.0. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128(41):13649–13650. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.