Summary

We present a case of a 45-year-old woman with a long-standing history of persistent cervical dysplasia that resulted in a hysterectomy. Subsequent vaginal smears revealed high-grade vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia (VAIN III) on Pap smear with positive human papilloma virus (HPV) testing. Over the course of 2 years, the patient underwent 2 CO2 laser vaporization procedures of the upper vagina and intermittent 5-fluorouracil therapy. A biopsy performed at the time of the second laser procedure revealed endocervical-type well-differentiated adenocarcinoma, associated with VAIN III. HPV in situ hybridization for HPV types 16 and 18 was positive in both the glandular and squamous mucosa. The patient has no known history of intrauterine diethylstilbestrol exposure or mullerian developmental abnormalities. Subsequently, the patient underwent a radical upper vaginetcomy with bilateral pelvic lymph nodes dissection and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. The vaginectomy specimen showed residual adenocarcinoma associated with VAIN-III and extensive vaginal adenosis with free resection margins. This is the second reported case in the literature of adenocarcinoma arising in vaginal adenosis after 5-fluorouracil. Herein, we highlight these important findings and shed some light on the pathogenesis of vaginal adenosis and the subsequent development of vaginal adenocarcinoma.

Keywords: Vagina, Adenocarcinoma, Adenosis, Human papillomavirus, 5-Fluorouracil

Vaginal adenosis is a rare entity that is most commonly observed in patients with in utero exposure to diethylstilbestrol (DES) or mullerian developmental anomalies. Although many cases of vaginal adenosis developing in patients after topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) therapy and CO2 laser ablation for a variety of conditions have been reported, the occurrence of adencoarcinoma is rarely observed (1–4).

Primary adenocarcinoma of the vagina is extremely rare, accounting for <1% of all gynecologic malignancies. The most common type that the literature has focused on is the clear cell type with its well-known association with in utero DES exposure and vaginal adenosis. The second most common subtype is endometrioid adenocarcinoma, which is most often associated with vaginal endometriosis (5).

Herein, we describe a case of endocervical-type primary adenocarcinoma of the vagina, arising in the setting of vaginal adenosis after therapy with 5-FU and multiple CO2 laser ablations for high-grade vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia (VAIN III) associated with human papilloma virus (HPV). To the best of our knowledge, this is the second reported case of adenocarcinoma occurring in this context ever described in the literature (1).

CASE REPORT

A 45-year-old White women with a longstanding history of abnormal Pap smears and cervical biopsies including high and low-grade cervical dysplasia, and positive testing for both high and low-risk HPV types, was referred to the gynecologic oncology service for follow-up and treatment. Her past medical history was unremarkable. Notably, there was no history of DES exposure or mullerian abnormalities. Despite treatment with laser conization and cryosurgery, she continued to have abnormal Pap smears, and she therefore underwent a hysterectomy in 2005 for definitive therapy. The patient has continued to have recurrent vaginal dysplasia since that time, with abnormal vaginal smears. She underwent a vaginal CO2 laser vaporization 2 years after her hysterectomy, after which she continued to have abnormal vaginal smears ranging from low to high-grade dysplasia. The patient was treated with 5-FU cream on and off for approximately 1 year, alternating with estrogen hormonal therapy. The patient then had a second vaginal laser vaporization, at which time an area with red granulation tissue was biopsied. After the biopsy diagnosis, the patient underwent a radical upper vaginectomy, bilateral pelvic lymph node dissection and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

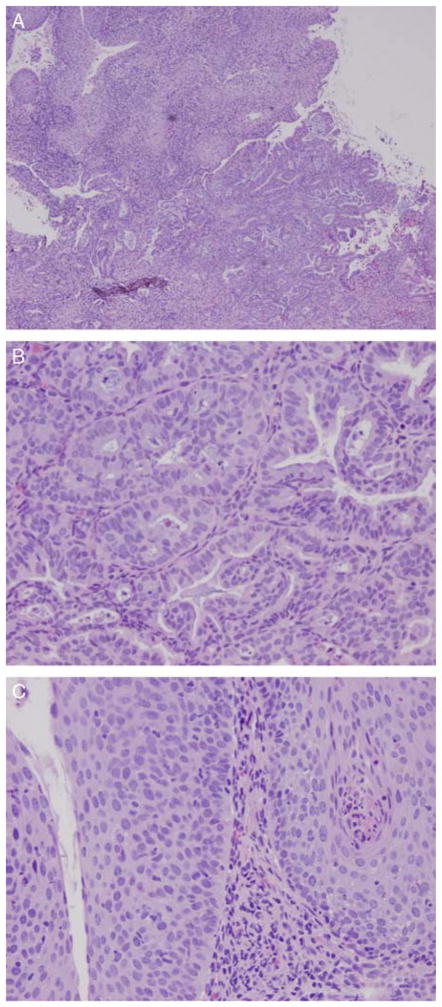

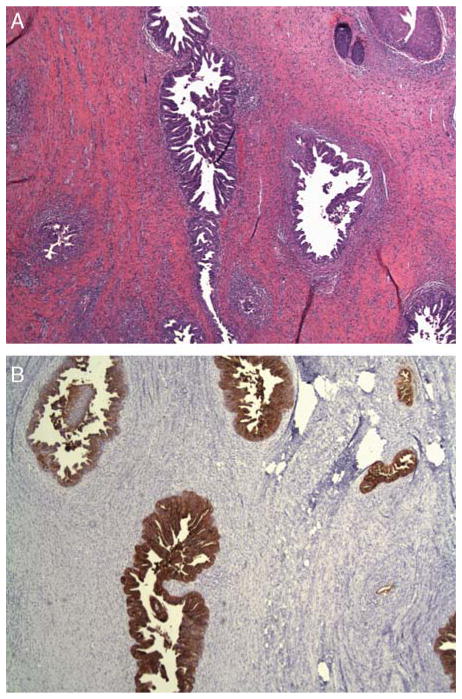

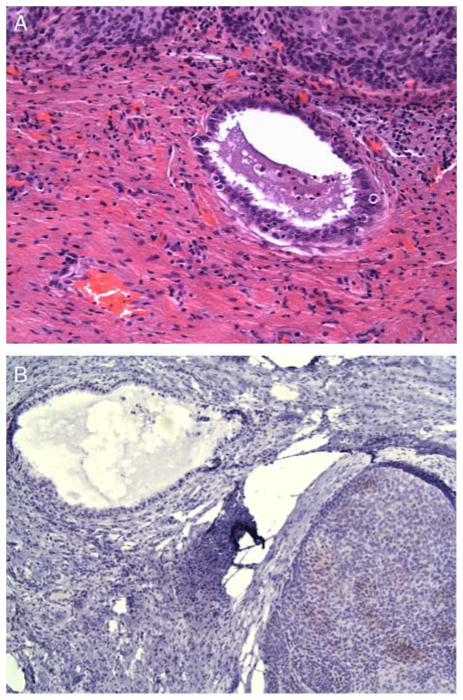

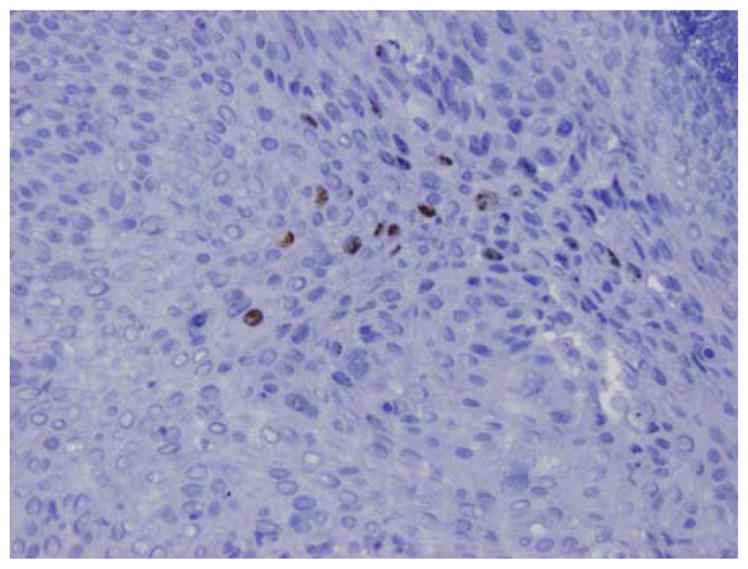

The vaginal biopsy revealed well-differentiated endocervical-type adenocarcinoma, measuring 0.3 × 0.2 cm associated with high-grade VAIN and extending to the resection biopsy site (Figs. 1A–C). Immunohistochemisty revealed neoplastic glands to be positive for AE1/3, CEA-m and negative for vimentin, and ER to be consistent with endocervical-type adenocarcinoma. In situ hybridization for highrisk HPV types 16 and 18 were positive in both squamous and glandular components (Fig. 2). The earlier hysterectomy specimen slides were reviewed and we confirmed the presence of low-grade cervical dysplasia and that the cervix was removed in its entirety. The upper vaginectomy specimen showed VAIN III of the anterior vagina associated with invasive, well-differentiated adenocarcinoma (CEA-positive) (Figs. 3A, B) arising in a background of vaginal adenosis (CEA-negative) (Figs. 4A, B). The margins were free of tumor and there was no evidence of metastatic disease.

FIG. 1.

(A) A low-power magnification of the vaginal biopsy hematoxylin and eosin section revealed a well-differentiated adenocarcinoma, and the overlying squamous mucosa showed high-grade vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia (10×). (B) The adenocarcinoma component consisted of back-to-back glands with slight nuclear atypia and few mitotic figures (40×). (C) The squamous mucosa overlying the adenocarcinoma shows a high-grade vaginal dysplasia in which the cells lacked normal maturation and reached the entire thickness of the squamous epithelium. Koilocytosis resulting from human papilloma virus effect are also present.

FIG. 2.

Human papilloma virus in situ hybridization for 16 and 18 subtypes show nuclear staining in the squamous and glandular epithelium (20×).

FIG. 3.

(A) The radical upper vaginectomy specimen shows residual well-differentiated adenocarcinoma positive for CEA antibody (B).

FIG. 4.

(A) In the background, areas of vaginal adenosis consistent with benign-looking endocervical-like glands are also present. These glands are negative for CEA antibody (B).

The patient did not have any postoperative complications. No further therapy was given and follow-up at 2 to 3-month intervals is planned.

HPV DNA Detection by In Situ Hybridization

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections were used. Biotin-labeled DNA-specific HPV probe solutions for types 16 and 18 were applied to individual sections. Detection of hybridized probe was performed by tyramid-catalyzed signal amplification using the Dako Genpoint Kit (Dakocytomation, CA). Chromogenic detection was performed with DAB/H2O2. Controls included tissue sections positive for HPV wide spectrum, the HeLa cell line for HPV 18 and the SiHa cell line for HPV 16. Biotin-labeled plasmid probes served as a negative control in each case. Cases with a discrete punctate reaction product in the cell nuclei were interpreted as positive.

DISCUSSION

The presence of vaginal adenosis is most commonly associated with DES exposure in utero, but can also be seen in cases of mullerian developmental disorders. In a series of autopsies examined by Sandberg (6), occult vaginal adenosis was found in 41% of postpubertal patients and in 0% of prepubertal patients, suggesting that adenosis develops de novo after puberty rather than during vaginal embryogenesis. More recently, there have been reports of vaginal adenosis after different types of vaginal trauma such as the application of 5-FU (1–3), CO2 laser vaporization (4), Stevens-Johnson syndrome (7) and contact irritation from a disinfectant used preoperatively (8). Although the pathogenesis of vaginal adenosis is still not completely understood, in cases of adenosis after vaginal trauma or irritation, it is suggested that adenosis develops as a metaplastic process similar to other well-known types of metaplasia that occur as a result of noxious stimuli in other parts of the body.

Vaginal adenocarcinomas are extremely rare, most commonly being clear cell carcinomas associated with in utero DES exposure (9). In nonexposed individuals, they are believed to arise from vaginal adenosis, endometriosis, or, rarely, Gartner’s duct remnants (10). To our knowledge, there has only been one earlier report in the literature of a vaginal adenocarcinoma arising in vaginal adenosis after 5-FU therapy. This case was a clear cell type diagnosed after treatment for condyloma acuminatum.

The relationship between HPV infection and genital neoplasia has been well established (11). There has been one other case reported in the literature showing HPV DNA in clear cell adenocarcinoma of the vagina (12). Our patient presented with well-differentiated endocervical-type adenocarcinoma, in a background of vaginal adenosis, following a long history of HPV infection and trauma secondary to multiple laser ablation procedures and prolonged 5-FU therapy. As there was no earlier biopsy to document the presence of adenosis, we could not be certain as to the lapse of time of progression from adenosis to carcinoma. In our case, the vaginal adenosis could be the result of numerous factors: (1) metaplastic process resulting from multiple traumas and injuries caused by 5FU and laser vaporization; (2) because occult adenosis is observed in postpuberal women, 5FU could unmask an occult adenosis and even stimulate its extension; (3) as HPV is well known to be a cancer initiating agents, a direct involvement of HPV in the malignant transformation of vaginal adenosis is also a plausible possibility; and (4) simply the combination of all these factors.

In conclusion, we report a case of well-differentiated endocervical-type adenocarcinoma of the vagina, arising in a background of vaginal adenosis after treatment of persistent VAIN-III with 5-FU and CO2 laser vaporization. This case supports the theory that vaginal adenosis can develop as a metaplastic process after trauma and not just embryologically. The finding of HPV DNA in the glandular epithelium suggests that HPV could be involved in the malignant transformation of vaginal adenosis to invasive adenocarcinoma. However, this issue is still open to discussion and speculation and more efforts are required to address it.

References

- 1.Goodman A, Zukerberg LR, Nikrui N, et al. Vaginal adenosis and clear cell carcinoma after 5-fluorouracil treatment for condylomas. Cancer. 1991;68:1628–32. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19911001)68:7<1628::aid-cncr2820680727>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dungar C, Wilkinson E. Vaginal columnar cell metaplasia. An acquired adenosis associated with topical 5-fluorouracil therapy. J Reprod Med. 1995;40:361–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bornstein J, Sova Y, Atad J, et al. Development of vaginal adenosis following combined 5-fluorouracil and carbon dioxide laser treatments for diffuse vaginal condylomatosis. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;81:896–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sedlacek TV, Riva JM, Magen AB, et al. Vaginal and vulvar adenosis: an unsuspected side-effect of carbon dioxide laser vaporiztion. J Reprod Med. 1990;35:995–1001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Staats PN, Clement PB, Young RH. Primary endometrioid adendocarcinoma of the vagina: a clinicopathologic study of 18 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:1490–501. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31804a7e9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sandberg EC. The incidence and distribution of occult vaginal adenosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1968;101:322–34. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(68)90058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marquette GP, Su B, Woodruff JD. Introital adenosis associated with Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 1985;66:143–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siders DB, Parrott MH, Abell MR. Gland cell prosoplasia (adenosis) of vagina. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1965;91:190–203. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(65)90200-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Melnick S, Cole P, Anderson D, et al. Rates and risks of diethylstilbestrol-related clear cell adenocarcinoma fo the vagina and cervix. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:514–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198702263160905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scurry J, Planner R, Grant P. Unusual variants of vaginal adenosis: a challenge for diagnosis and treatment. Gynecol Oncol. 1991;41:172–7. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(91)90280-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pater MM, Pater A. Expression of human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 DNA sequences in cervical carcinoma cell lines. J Med Virol. 1988;26:185–95. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890260210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ikenberg H, Runge M, Goppinger A, et al. Human papillomavirus DNA in invasive carcinoma of the vagina. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;76:432–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]