An investigation of a Legionnaires' disease outbreak at a Cozumel Island resort identified the source of the first reported Legionnaires' disease outbreak in Mexico and highlighted the need for all countries to make Legionnaires' disease a reportable disease.

Keywords: community-acquired pneumonia, legionellosis, Legionnaires' disease

Abstract

Background. A Legionnaires' disease (LD) outbreak at a resort on Cozumel Island in Mexico was investigated by a joint Mexico-United States team in 2010. This is the first reported LD outbreak in Mexico, where LD is not a reportable disease.

Methods. Reports of LD among travelers were solicited from US health departments and the European Working Group for Legionella Infections. Records from the resort and Cozumel Island health facilities were searched for possible LD cases. In April 2010, the resort was searched for possible Legionella exposure sources. The temperature and total chlorine of the water at 38 sites in the resort were measured, and samples from those sites were tested for Legionella.

Results. Nine travelers became ill with laboratory-confirmed LD within 2 weeks of staying at the resort between May 2008 and April 2010. The resort and its potable water system were the only common exposures. No possible LD cases were identified among resort workers. Legionellae were found to have extensively colonized the resort's potable water system. Legionellae matching a case isolate were found in the resort's potable water system.

Conclusions. Medical providers should test for LD when treating community-acquired pneumonia that is severe or affecting patients who traveled in the 2 weeks before the onset of symptoms. When an LD outbreak is detected, the source should be identified and then aggressively remediated. Because LD can occur in tropical and temperate areas, all countries should consider making LD a reportable disease if they have not already done so.

Legionnaires' disease (LD) is a potentially fatal form of pneumonia caused by Legionella bacteria. Infection usually results from the inhalation of aerosols containing Legionella bacteria that are capable of amplifying in man-made water systems such as cooling towers, whirlpool spas, and potable water systems [1–3]. Although LD cases may be underdiagnosed, the number of LD cases reported in the United States and Europe has been rising since 2000, indicating the importance of understanding and controlling LD [4–6]. Legionnaires' disease outbreaks have been identified in tropical areas such as the Virgin Islands and Singapore as well as in temperate areas such as the continental United States and Europe [1, 2, 5, 7, 8], but only sporadic LD cases have been previously reported in Mexico [9]. Legionnaires' disease is currently neither a reportable disease nor under surveillance in Mexico.

In late 2009 and early 2010, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) received 6 reports of LD among international travelers who had recently stayed at the same resort on tropical Cozumel Island in the Mexican state of Quintana Roo, meeting the CDC criteria for an outbreak because at least 2 individuals had developed LD after being exposed to the same location at approximately the same time [10]. Two similar reports previously forwarded to the Pan American Health Organization, the earliest from May 2008, were found on retrospective review of CDC records. Only 2 additional LD cases with onset of symptoms between 2008 and April 2010 were reported among US travelers to Cozumel who did not stay at the resort, further indicating that the resort was associated with an unusually large number of LD cases. In response to this outbreak, the Mexican Secretariat of Health, the Quintana Roo Secretariat of Health, and the CDC conducted a joint field investigation of this LD outbreak in April 2010 according to the principles contained in the Technical Guidelines for United States-Mexico Coordination on Public Health Events of Mutual Interest [11].

METHODS

Outbreak Identification

Cases of LD in the United States are reported to local or state health authorities. State health departments in turn notify the CDC of LD cases they learn of directly or through local health departments. Because travel-related LD outbreaks may affect travelers widely dispersed throughout the United States, sometimes making identification of such outbreaks difficult for individual local or state health departments, states are encouraged to include information about recent travel in their reports to the CDC of LD cases [4]. Foreign governments, particularly those associated with the multinational European Working Group for Legionella Infections ([EWGLI] now called the European Legionnaires' Disease Surveillance Network), also report cases of LD to the CDC, especially when they involve travelers to the United States [4].

Epidemiological Investigation

At the time of the April 2010 joint Mexico-US field investigation, a confirmed LD case connected to the outbreak was defined as laboratory-confirmed LD with onset during the resort stay or within 2 weeks of departure from the resort between May 2008 and April 2010. Laboratory evidence of Legionella infection potentially included at least 1 of the following: isolation through culture of any Legionella organism from respiratory secretions, lung tissue, pleural fluid, or other normally sterile fluid; detection of Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1 antigen in urine; or seroconversion, specifically a 4-fold or greater rise in specific serum antibody titer to L pneumophila serogroup 1 between acute and convalescent titers. A possible LD case was defined as pneumonia consistent with a diagnosis of LD with onset during the resort stay or within 2 weeks of departure from the resort between May 2008 and April 2010 in which there was no other explanation for pneumonia besides LD but also no available laboratory confirmation of LD.

Several methods were used to identify cases of LD related to the resort. First, CDC staff reviewed reports of LD cases received by the CDC to identify any reports associated with the resort. Second, in March 2010, CDC staff requested information on any LD cases linked to the resort through a posting on Epi-X, the CDC's secure website for sharing information among CDC, US state and local health departments, and other public health agencies. Finally, Mexican Secretariat of Health staff searched for confirmed or possible LD cases treated on Cozumel Island during May 2008 to April 2010 by reviewing records from the resort, which had an on-call doctor available to see guests, the Cozumel Mexican Institute for Social Security (IMSS) clinic, which cares for sick resort employees and assesses their requests for medical leaves, and the San Miguel Health Center, the main general medical facility on Cozumel Island.

For cases of laboratory-confirmed LD linked to the resort among international travelers, staff from the CDC, state health departments in the United States, and EWGLI collected additional information through interviews with patients. Because this investigation was an emergency response to an outbreak of a potentially life-threatening disease, it was designated exempt from ethical committee review and requirements for written informed consent under the CDC's and Mexican Secretariat of Health's human subject policies.

Clinical Laboratory Testing

A sputum specimen from 1 case with onset of symptoms in March 2010 was received from a clinical laboratory and tested at the CDC Legionella laboratory. Once Legionella was cultured from the specimen, the species and serogroup were determined [12, 13], and the isolate underwent monoclonal antibody (MAb) typing with an international panel of 7 MAbs using a dot blot method [14, 15]. Molecular sequence-based typing (SBT) was performed to create 7 gene, allelic profiles (flaA, pilE, asd, mip, mompS, proA, neuA) and determine sequence types (STs) of select L pneumophila serogroup 1 isolates [16, 17].

Environmental Assessment and Testing

A team from the Mexican Secretariat of Health, the Quintana Roo Secretariat of Health, and the CDC visited the resort in April 2010, searched the resort for possible sources of Legionella exposure, and reviewed the resort's maintenance and Legionella prevention measures. The team also measured the temperature and total chlorine of the water at 38 potable, decorative, and recreational water sites in the resort and collected 119 bulk water and biofilm swab samples from those 38 sites according to previously published standard procedures [18]. Bulk water samples were collected in 1-liter sterile bottles with 0.5 mL of 0.1 N sodium thiosulfate added to neutralize chlorine. Biofilms inside plumbing fixtures were sampled with a Dacron-tipped swab and then placed in 3 to 5 mL water (to prevent drying during transport) with 2 to 3 drops of 0.1 N sodium thiosulfate solution. Water for the biofilm swabs came from the same site as where the swab was collected. Those samples were cultured at the CDC Legionella laboratory using previously published standard procedures [18]. Isolates were screened for L pneumophila serogroup 1 using specific L pneumophila serogroup 1 MAb reagents [13]. Selected L pneumophila serogroup 1 isolates also underwent MAb typing and ST identification [15–17].

RESULTS

Epidemiological Investigation

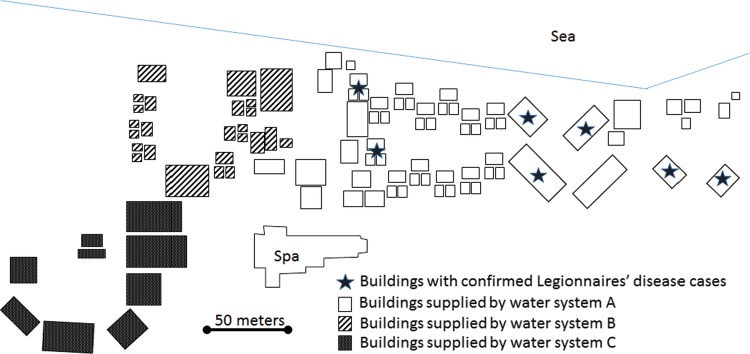

Nine confirmed LD cases were identified among international travelers with onset of symptoms within 2 weeks of staying at the resort between May 2008 and April 2010 (Figure 1). Six cases were reported in late 2009 and early 2010, 2 cases reported in June 2008 and May 2009 were found during a retrospective records review, and 1 case with onset of symptoms in March 2010 was reported to the CDC in January 2011. Eight reports involved residents of the United States, whereas the ninth case involved a resident of the Netherlands interviewed and reported to the CDC by EWGLI. All cases had positive L pneumophila serogroup 1 urine antigen tests, and 1 case was Legionella culture-positive at the CDC. All 9 individuals with LD were hospitalized, and all recovered from their illnesses.

Figure 1.

Confirmed Legionnaires' disease cases by month of onset, May 2008–April 2010.

All 9 individuals with confirmed LD were ≥50 years old (Table 1). Four individuals were either current or former smokers, and 6 had at least 1 chronic disease known to be associated with increased risk for LD, specifically diabetes, coronary artery disease, rheumatoid arthritis treated with an immunosuppressant, leukemia, chronic lung disease, or chronic liver disease. The resort was the only common exposure identified among the individuals with confirmed LD. Two individuals did not visit any other attractions or restaurants on Cozumel during their trips. All 9 individuals used their room showers during their stays, and 4 also used nonguest room resort showers at the resort's beach. Only 1 individual used the resort spa.

Table 1.

Characteristics and Exposures of Confirmed Legionnaires' Disease Cases Among Resort Guests, May 2008 to April 2010

| Characteristic or Exposure | Number With Characteristic (%) |

|---|---|

| Age ≥50 y | 9 (100) |

| Male Sex | 5 (56) |

| Current or former smoker | 4 (44) |

| Chronic diseasea | 6 (67) |

| Used room shower | 9 (100) |

| Used beach shower | 4 (44) |

| Used resort spa | 1 (11) |

| Visited other island attractions or restaurants | 7 (78) |

a Chronic disease includes diabetes, coronary artery disease, rheumatoid arthritis treated with an immunosuppressant, leukemia, chronic lung disease, and chronic liver disease.

An additional possible LD case was identified during the interviews of the individuals with confirmed LD. The individual with possible LD had onset of pneumonia in November 2009 within 5 days of a stay at the resort but was not tested for LD. This individual was a >50-year-old male nonsmoker with a history of diabetes who stayed at the resort as part of the same group as a confirmed case. He was hospitalized but survived his illness.

No additional confirmed or possible LD cases were found on review of the resort's records or records from the IMSS clinic or the San Miguel Health Center, including among the employees of the resort. The resort's records indicated that the resort's on-call doctor usually saw 2 to 3 respiratory infections each year, all of which were clinically classified as pharyngitis or bronchitis, and that there had not been an increase in the number of cases seen in recent years. The reviews of the records at the IMSS clinic and the San Miguel Health Center did not identify any unexplained pneumonia cases in working age adults or serious lower respiratory tract infections connected to the resort.

Clinical Laboratory Testing

A sputum specimen from 1 case-patient with onset of symptoms in March 2010 was received from a clinical laboratory and successfully cultured for Legionella at the CDC Legionella laboratory. This isolate was determined to be L pneumophila serogroup 1, MAb pattern (1, 2, 5, *) and ST 42. (The asterisk indicates MAb 6 was not tested due to low supply of typing sera.)

Environmental Assessment and Testing

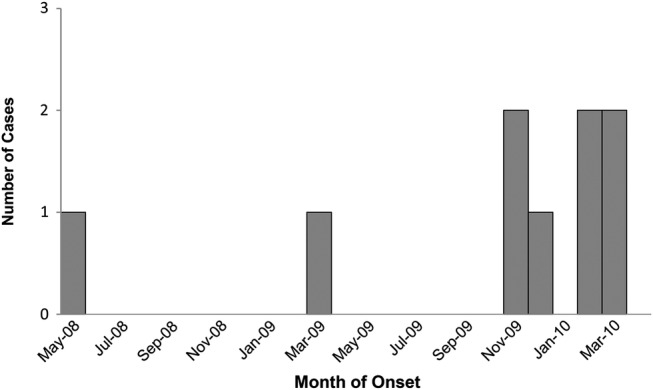

The resort had 312 guest rooms and 3 separate potable hot water systems (Figure 2). Each hot water system used its own water heater and kept its heated water in its own storage tank until the water was sent via pipe to a faucet or shower. Water system A provided all water for the resort buildings where the individuals with confirmed LD stayed. The resort did not have any water-based air cooling systems such as cooling towers, but it did have a spa building containing whirlpool spas and a decorative water fountain. The resort's maintenance staff routinely added halogens such as chlorine to the whirlpool spas and swimming pools but not to the rest of the potable water system.

Figure 2.

Confirmed Legionnaires' disease cases by location of patient stay, May 2008–April 2010. (Note: Some buildings had multiple confirmed Legionnaires' disease cases.)

Of the 119 water samples collected for Legionella testing, 104 (87%) were positive for a Legionella species, and 93 (78%) specifically contained L pneumophila serogroup 1, sometimes in combination with Legionellae other than L pneumophila serogroup 1. Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1 was found in all 3 of the resort's hot water systems and the guest rooms they provided water to as well as in the hot water tanks of water systems B and C. Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1 with MAb pattern (1, 2, 5,*) and ST 42, the pattern and type matching the clinical isolate, was found in water systems A and B. No Legionellae were found in the spa building's whirlpool spas. Tests of 2 whirlpool spas showed >3.5 ppm of chlorine, but no residual chlorine was found in the water from the resort's potable water systems. The water from the hot water tanks supplying the 3 water systems had temperatures ranging from 39.3 to 46.0°C.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first identified LD outbreak in Mexico. The findings suggest the resort's potable water system was the common source of infection. First, use of the resort's potable water system, such as showering in guest rooms, was the only identified common exposure to aerosolized water among the cases. A source outside of the resort was unlikely because the cases did not report any common exposures besides the resort during the possible incubation periods for their illnesses. Second, the potable water system's water temperatures and chlorine levels were compatible with Legionella growth because Legionella can amplify at temperatures of 25 to 42°C, particularly in the absence of chlorine or other halogens [3, 19]. Third, Legionellae were found to have extensively colonized the resort's potable water system. Finally, the 1 clinical isolate obtained from this outbreak matched Legionella found in the potable water system of this resort. This LD outbreak underscores the importance of the Infectious Disease Society of America's recommendation that medical providers test for LD when treating patients with community-acquired pneumonia who have traveled anywhere in the 2 weeks before the onset of symptoms as well as patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia [20]. Both urine antigen tests for Legionella and culture of respiratory specimens for Legionella can be useful diagnostic options for such patients [4, 20], as was the case in this outbreak. However, collection of respiratory specimens can be particularly helpful because such specimens allow the detection of all species and serogroups of Legionella and enable the identification of the strain causing an outbreak, which in turn can facilitate the identification of the outbreak source [4, 8]. When combined with prompt reporting of LD cases to public health authorities, aggressive testing can lead to better identification, investigation, and control of LD outbreaks in all countries, including the United States [4].

International cooperation was essential for the investigation of this outbreak. The outbreak was detected due to reports of cases among travelers from the United States and Europe, but both the site visit that confirmed the source and the search for cases among local residents depended on work by Mexican public health authorities. Due to the many LD cases reported each year that are related to the more than 1 billion annual overnight international trips [4, 5, 21], international cooperation will continue to be important in responding to future LD outbreaks [22], some of which might be further complicated by multinational ownership or operation of the source facility. Although ad hoc joint investigations are a viable option for organizing international cooperative efforts in dealing with LD outbreaks, more formalized cooperative mechanisms, such as the European Legionnaires' Disease Surveillance Network, can be very effective, as shown by that network's history of success in identifying and responding to LD outbreaks [22].

Efforts to identify and respond to international as well as domestic LD outbreaks would be strengthened if all countries required medical providers and laboratories to report laboratory-confirmed cases of LD to public health authorities. Because LD outbreaks have been reported in a range of temperate and tropical countries, it is likely that LD can occur in any area with man-made systems with warm water such as cooling towers, whirlpool spas, and potable water systems [1–3, 5, 7, 8]. Legionnaires' disease outbreaks linked to such water systems can occur at buildings other than hotels and resorts, including long-term care facilities, hospitals, industrial and office workplaces, and residential buildings [6]. In addition to facilitating identification of LD cases among travelers from all countries, a reporting requirement would aid public health authorities of countries in which LD is not currently a reportable disease in identifying and controlling their domestic LD outbreaks.

Ensuring that all countries have access to public health laboratories with the capacity to test clinical and environmental samples for Legionellae would also facilitate detection of and response to LD outbreaks. In addition to the ability to culture for Legionellae and perform Legionellae urine antigen testing, laboratories would benefit from the ability to perform SBT and other genetic analyses of detected Legionellae because such testing can allow more detailed analyses of connections between Legionellae found in clinical and environmental samples and, in some cases, characterization of Legionellae from such samples that could not be cultured [23–25]. For example, if more Legionella isolates from clinical samples had been available during this investigation, genetic testing might have found that multiple strains of L pneumophila serogroup 1 had caused the LD cases, as was the case in an LD outbreak at a hotel in Calp, Spain [24].

The lack of cases identified among local residents, including resort employees, in this outbreak is consistent with the findings of multiple previous investigations of LD outbreaks at hotels and resorts. Investigations of LD outbreaks at hotels in Ocean City, Maryland [26], Orlando, Florida [27], and Las Vegas, Nevada did not identify any LD cases among hotel employees [2]. The first investigation of an LD outbreak, which centered on a hotel in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, found that only 1 of the 182 illnesses that met that investigation's case definition occurred among the hotel's more than 400 employees, and that illness was more likely an upper respiratory infection than true LD [28]. The frequent lack of LD cases among employees of hotels experiencing LD outbreaks among travelers may in part be due to the fact that the hotel employees are likely younger and healthier than the travelers who develop LD. In addition, hotel employees may be less likely to have exposures that could lead to LD transmission, such as use of the hotel's showers or hot water spas. However, hotel employees can also be at risk from LD, as shown by the LD outbreak at a hotel in Calp, Spain in which 6 of 44 identified LD cases occurred in hotel employees [24, 29]. Investigators of hotel LD outbreaks identified due to LD cases among travelers should consider ruling out cases among hotel employees to ensure that investigations do not overlook possible sources of Legionella that could be revealed through cases' exposure histories as well as to assuage potential local fears of a larger outbreak.

This investigation had several limitations. The 9 cases of confirmed LD and 1 case of possible LD identified in this outbreak are likely an underestimate because empiric antibiotic therapy is often used for pneumonia treatment and LD is not a reportable disease in all countries. In particular, the fact that LD was not a reportable disease in Mexico increases the likelihood that Mexican healthcare providers would not diagnose or report LD cases. In addition, the efforts to identify possible LD cases among hotel employees would not have detected cases among employees who did not seek medical care for lower respiratory tract infections during the time of the outbreak or who sought care from a healthcare facility other than the 2 whose records were actively reviewed. These limitations underscore the importance of healthcare providers being alert to the possibility of LD and reporting LD cases to public health authorities. In addition, we did not compare the characteristics or behaviors of the cases with the characteristics or behaviors of travelers who stayed at the resort and did not develop LD or hotel employees or collect the data needed for such a comparison. However, despite this limitation, the environmental assessment and testing findings, the match between the clinical isolate and some of the environmental isolates, and the fact that use of the resort's potable water system was the only common exposure to aerosolized water among the cases all indicate that the resort's potable water system was the common source of infection in this outbreak.

Once an international travel-related LD outbreak is recognized, both close coordination between the relevant countries and an aggressive response, including effective remediation of the source of infection [3], are important for preventing further disease transmission. Ongoing Legionella control measures are essential following remediation [1–3], particularly because outbreaks have recurred when Legionella remediation efforts were not sufficient to reduce the amount of Legionella bacteria in an affected water system to undetectable levels [2]. Such a recurrence may have affected this resort because 4 additional LD cases among travelers who stayed at the resort have been reported to the CDC since the investigation over a 5-year period. Ongoing vigilance to implement and assess the effectiveness of interventions to control Legionella are paramount. Continued monitoring of water systems to assess temperature, disinfection levels, and Legionella colonization at a facility affected by an outbreak, such as this resort, can help confirm whether or not the control measures are effective [1–3]. In addition, an experienced Legionella remediation consultant can provide valuable aid in the planning and execution of a Legionella testing and control strategy. The development of such expertise in countries where it is not readily available can contribute to public health capacity. Some countries, including ones with substantial tourist industries, have adopted regulations regarding maintenance, testing, and treatment of water systems and other possible Legionella sources [7, 30]. Because Legionellae are likely ubiquitous in man-made water systems, all countries should promote effective LD prevention and surveillance measures and should be prepared to cooperate in detecting and responding to LD outbreaks [3].

CONCLUSIONS

This LD outbreak illustrates the importance of medical providers testing for LD when treating patients with community-acquired pneumonia who have traveled anywhere in the 2 weeks before the onset of symptoms. When an LD outbreak is detected, both a careful investigation to identify the outbreak source and aggressive remediation of the identified outbreak source are essential and may require international cooperation if the outbreak is identified due to LD cases among international travelers. In hotel LD outbreak investigations prompted by LD cases among travelers, efforts to identify LD cases among hotel employees may be useful. Because LD can occur in both tropical and temperate areas, all countries should consider making LD a reportable disease if they have not already done so.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of the resort for their cooperation with this investigation, particularly the local management of the resort for facilitating the environmental investigation and responding positively to the recommendations for Legionnaires' disease remedial interventions and preventive measures. We also thank numerous personnel at the Quintana Roo Secretariat of Health, the Dirección General de Epidemiología, the Instituto de Diagnóstico y Referencia Epidemiológicos, the Comisión Federal para la Protección contra Riesgos Sanitarios, the Alaska Department of Health and Social Services, the California Department of Public Health, the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, the Delaware Department of Health and Social Services, the Illinois Department of Public Health, the Nevada Department of Health and Social Services, the Pennsylvania Department of Health, the Washington Department of Health, the Wisconsin Department of Health Services, and the European Working Group for Legionella Infections for their assistance with case finding and data collection during this investigation.

Disclaimer. The findings and conclusions in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Connecticut Department of Public Health, the Mexican Secretariat of Health, or the Quintana Roo Secretariat of Health.

Financial support. This work was supported by funds from the Global Disease Detection Program, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Mexican Secretariat of Health.

Potential conflicts of interest. L. M. H., J. K., N. A. K.-M., C. L., B. F, L. S., T. M.-E., S. W., L. A. H. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Cowgill KD, Lucas CE, Benson RF et al. . Recurrence of Legionnaires disease at a hotel in the United States Virgin Islands over a 20-year period. Clin Infect Dis 2005; 40:1205–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Silk BJ, Moore MR, Bergtholdt M et al. . Eight years of Legionnaires’ disease transmission in travellers to a condominium complex in Las Vegas, Nevada. Epidemiol Infect 2012; 140:1993–2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Society of Heating Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers. ASHRAE Guideline 12-2000: minimizing the risk of legionellosis associated with building water systems. Atlanta: ASHRAE, 2000:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Legionellosis --- United States, 2000–2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2011; 60:1083–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Legionnaires’ disease in Europe, 2012. Stockholm: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garrison LE, Kunz JM, Cooley LA et al. . Vital signs: deficiencies in environmental control identified in outbreaks of Legionnaires’ disease - North America, 2000–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016; 65:576–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lam MC, Ang LW, Tan AL et al. . Epidemiology and control of legionellosis, Singapore. Emerg Infect Dis 2011; 17:1209–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fields BS, Benson RF, Besser RE. Legionella and Legionnaires’ disease: 25 years of investigation. Clin Microbiol Rev 2002; 15:506–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huerta-Torrijos J, Lisker-Halpert A, Nunez-Perez RC et al. . [Atypical pneumonia caused by Legionella pneumophila. Report of a second case in Mexico]. Gac Med Mex 1995; 131:587–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ambrose J, Hampton LM, Fleming-Dutra KE et al. . Large outbreak of Legionnaires’ disease and Pontiac fever at a military base. Epidemiol Infect 2014; 142:2336–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Technical Guidelines for United States-Mexico Coordination on Public Health Events of Mutual Interest, 2015. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/USMexicoHealth/pdf/us-mexico-guidelines.pdf Accessed 21 March 2016.

- 12.Benson RF, Fields BS. Classification of the genus Legionella. Semin Respir Infect 1998; 13:90–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Travis TC, Brown EW, Peruski LF et al. . Survey of Legionella species found in Thai soil. Int J Microbiol 2012; 2012:218791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanden GN, Cassiday PK, Barbaree JM. Rapid immunodot technique for identifying Bordetella pertussis. J Clin Microbiol 1993; 31:170–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joly JR, McKinney RM, Tobin JO et al. . Development of a standardized subgrouping scheme for Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1 using monoclonal antibodies. J Clin Microbiol 1986; 23:768–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaia V, Fry NK, Afshar B et al. . Consensus sequence-based scheme for epidemiological typing of clinical and environmental isolates of Legionella pneumophila. J Clin Microbiol 2005; 43:2047–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ratzow S, Gaia V, Helbig JH et al. . Addition of neuA, the gene encoding N-acylneuraminate cytidylyl transferase, increases the discriminatory ability of the consensus sequence-based scheme for typing Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1 strains. J Clin Microbiol 2007; 45:1965–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Procedures for the recovery of Legionella from the environment. Atlanta, GA: Department of Health and Human Services, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Silk BJ, Foltz JL, Ngamsnga K et al. . Legionnaires’ disease case-finding algorithm, attack rates, and risk factors during a residential outbreak among older adults: an environmental and cohort study. BMC Infect Dis 2013; 13:291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A et al. . Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 44(Suppl 2):S27–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Tourism Organization. UNWTO Tourism Highlights, 2016 Edition, 2015. Available at: http://www.e-unwto.org/doi/book/10.18111/9789284418145 Accessed 24 August 2016.

- 22.World Health Organization. Legionella and the Prevention of Legionellosis. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dooling KL, Toews KA, Hicks LA et al. . Active bacterial core surveillance for legionellosis - United States, 2011–2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015; 64:1190–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sanchez-Buso L, Guiral S, Crespi S et al. . Genomic investigation of a legionellosis outbreak in a persistently colonized hotel. Front Microbiol 2015; 6:1556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McAdam PR, Vander Broek CW, Lindsay DS et al. . Gene flow in environmental Legionella pneumophila leads to genetic and pathogenic heterogeneity within a Legionnaires’ disease outbreak. Genome Biol 2014; 15:504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Legionnaires disease associated with potable water in a hotel--Ocean City, Maryland, October 2003-February 2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2005; 54:165–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hlady WG, Mullen RC, Mintz CS et al. . Outbreak of Legionnaire's disease linked to a decorative fountain by molecular epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol 1993; 138:555–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fraser DW, Tsai TR, Orenstein W et al. . Legionnaires’ disease: description of an epidemic of pneumonia. N Eng J Med 1977; 297:1189–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vanaclocha H, Guiral S, Morera V et al. . Preliminary report: Outbreak of Legionnaires disease in a hotel in Calp, Spain, update on 22 February 2012. Euro Surveill 2012; 17:pii=20093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parr A, Whitney EA, Berkelman RL. Legionellosis on the rise: a review of guidelines for prevention in the United States. J Public Health Manag Pract 2015; 21:E17–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]