An inpatient penicillin allergy skin testing program can be successfully managed by infectious diseases fellows under attending supervision offering a novel practice area for infectious diseases practitioners.

Keywords: allergy, β-lactam, penicillin

Abstract

Background. A large percentage of patients presenting to acute care facilities report penicillin allergies that are associated with suboptimal antibiotic therapy. Penicillin skin testing (PST) can clarify allergy histories but is often limited by access to testing. We aimed to implement an infectious diseases (ID) fellow-managed PST program and to assess the need for PST via national survey.

Methods. We conducted a prospective observational study of the implementation of an ID fellow-managed penicillin allergy skin testing service. The primary outcome of the study was to assess the feasibility and acceptability of an ID fellow-managed PST service and its impact on the optimization of antibiotic selection. In addition, a survey of PST practices was sent out to all ID fellowship program directors in the United States.

Results. In the first 11 months of the program, 90 patients were assessed for PST and 76 patients were tested. Of the valid tests, 96% were negative, and 84% with a negative test had antibiotic changes; 63% received a narrower spectrum antibiotic, 80% received more effective therapy, and 61% received more cost-effective therapy. The majority of survey of respondents (n = 50) indicated that overreporting of penicillin allergy is a problem in their practice that affects antibiotic selection but listed inadequate personnel and time as the main barriers to PST.

Conclusions. Inpatient PST can be successfully managed by ID fellows, thereby promoting optimal antibiotic use in patients reporting penicillin allergies. This model can increase access to PST at institutions without adequate access to allergists while also providing an important educational experience to ID trainees.

Up to 15% of inpatients report an allergy to penicillin antibiotics [1]. Type I immunoglobulin (Ig)E-mediated hypersensitivity reactions (urticaria and anaphylaxis) are potentially life threatening; identification of patients at high risk for these reactions is critical in preventing avoidable morbidity and mortality. In contrast, patient self-report of antibiotic allergy has been associated with antimicrobial resistance, increased length of stay (LOS), increased cost, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, and death [2, 3]. Identifying those patients with reported penicillin allergy who are actually at low risk for IgE-mediated reactions allows for optimized antimicrobial therapy.

The penicillin skin test (PST) assesses local reactions to minute doses of penicillin metabolites, which include major and minor determinants, responsible for >80% and <10% of type I reactions, respectively. The major determinants are penicilloyl haptens, commercially available as benzylpenicilloyl polylysine ([PPL] Pre-pen; ALK-Abello, Inc., Round Rock, TX). Minor determinants are penicillenyl and penicillamine haptens, found in injectable penicillin G (PCN G) [4].

The penicillin skin test has a negative predictive value of 97%–99% for IgE-mediated reactions, and the risk for such reactions in patients with a negative test corresponds to that of the general population [5, 6]. Multiple studies have demonstrated a positive impact of PST on antibiotic utilization and cost-effectiveness in various settings and populations [7, 8]. However, in clinical practice, PST is often not readily available. A survey of the Infectious Disease Society of America Emerging Infections Network found that of 744 members who responded (53% response rate), only 60% had PST available at their institutions. Of those, 90% indicated that testing was performed by allergy and/or immunology physicians [9]. Allergists mainly offer assessment and testing for outpatients, and therefore the unavailability of PST is a particular problem for acute inpatient care and hospital antibiotic stewardship. Therefore, we were interested in evaluating the integration of PST into infectious diseases (ID) practice and training, providing a model to optimize antibiotic use in the hospital.

In addition, ID as a specialty is struggling under the current procedure-oriented, fee-for-service reimbursement system [10]. A decreasing interest in ID fellowship training, as evidenced by 117 of 335 ID fellowship positions remaining unfilled this year, might be related and is of concern [11, 12]. However, responsibilities for antimicrobial stewardship and hospital infection control are growing areas for ID-trained physicians [10]. An academic hospital with an ID training program might be a promising setting for integrating PST into ID practice by engaging ID fellows in antimicrobial stewardship and training them in a novel procedure. Incorporating PST into an ID fellowship curriculum could also increase access to PST on a larger scale as program graduates go out into the community to practice.

At the University of Maryland Medical Center (UMMC), a 1-year pilot of PST in the Medical Intensive Care Unit (MICU) was completed under management of the MICU ID consult team. Given its success, a more sustainable model for testing was desired so the service was formalized into a hospital-wide penicillin allergy consult service for adult patients. The objectives of this manuscript are to describe the implementation of an ID fellow-managed penicillin allergy consult service and assess the perceived need for such a service with a national survey of ID fellowship program directors.

METHODS

A prospective observational study of the implementation of an ID fellow-managed penicillin allergy service was conducted at UMMC. The UMMC is a 757-bed academic medical center offering 6 ID consult services (general, surgical, solid organ transplant, cancer and hematopoietic stem cell transplant, medical intensive care, and trauma) and 1 primary internal medicine service, which cares for patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and other infections. The adult ID fellowship is a 2-year accredited training program with 7 fellows per year. The study was recognized by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) as a Quality Assessment Project.

Training

At the beginning of the academic year, ID fellows and interested ID faculty received education and training on PST, including practical preparation and a didactic lecture. Initial training was given onsite by representatives from ALK-Abello with subsequent trainings and refresher courses led by “super-users”. Training included hands-on demonstration using actual testing supplies and volunteers with reported penicillin allergy from department staff. Super-users were 3 ID faculty who had received training from ALK-Abello and had the most experience with testing. Competency was assessed via a checklist that was evaluated by one of the super-users. All providers also had access to web-based videos, a slide presentation, and suggested literature. Individualized follow-up training sessions for the fellows before their scheduled penicillin allergy service month were also provided. The most flexible scheduling for an ID fellow to perform the penicillin allergy consults was during the rotation on the internal medicine ID/HIV service, where their primary role is teaching.

Testing

Recruitment of patients had 3 pathways: (1) the antimicrobial stewardship team through the daily antibiotic and chart reviews, (2) ID consult service, or (3) the primary team requesting a consult via dedicated pager. The availability of the penicillin allergy service was advertised broadly among the different inpatient services, and the ID fellow covering the service carried a dedicated penicillin allergy service pager. After a request for consultation, fellows performed detailed drug allergy histories and determined appropriateness for PST. Patients were excluded from PST if their allergy history revealed an anaphylactic reaction to a penicillin within 5 years, if they had tolerated the desired post-PST antibiotic in the past, or if there was a history of any serious non-Type 1 adverse reaction to a penicillin, cephalosporin, or carbapenem. Serious adverse reactions included Type 2, 3, and 4 drug reactions, which are contraindications to PST or rechallenge [5]. Penicillin skin test eligibility was ultimately determined by the ID fellow and ID attending physician based on the allergy history and on consideration on how test results may influence further therapy. For example, if the history of a patient with a reported penicillin allergy revealed that the patient had tolerated a cephalosporin in the past, and a cephalosporin was an appropriate treatment option for the patient, the team would not have pursued testing for that patient. However, if the target antibiotic therapy for that same patient was nafcillin, the team would have pursued PST because tolerance of ceftriaxone does not indicate the patient would tolerate nafcillin. Patients who were eligible and consented to PST had the skin test performed by the fellow with ID attending physician supervision.

The test kit was dispensed from the pharmacy and included PPL, PCN G potassium diluted to a concentration of 10 000 units/mL, histamine control (positive control), preservative-free sodium chloride 0.9% (negative control), and 1 amoxicillin 250 mg capsule. The preliminary prick test was performed with the Duotip-test II applicator device (Lincoln Diagnostics, Inc., Decatur, IL) using the PPL, PCN G, positive control, and negative control. Appearance of erythema and a wheal diameter of ≥3 mm greater than the negative control was indicative of a positive test. A negative reaction to the histamine control was considered an indeterminate test. If the prick tests were negative or equivocal, intradermal testing was done by applying duplicate 3 mm blebs of PPL and PCN G and 1 bleb of sodium chloride 0.9% and examining them after 15 minutes. If there was no response, defined as no increase in size of original bleb and no reaction greater than the control site, the test was considered negative [5]. Negative tests were followed with a single oral dose of amoxicillin 250 mg or the definitive non-aztreonam β-lactam therapy. A core group of ID attending physicians with expertise in PST provided supervision on an alternating basis. Additional ID attending physicians who were comfortable with the procedure and had prior training supervised fellow-directed PST for their own patients while on a consult service.

Recommendations for definitive antibiotic therapy based on PST result were made by the responsible ID consult service/attending. If patients had not been seen by one of the ID consult teams until PST, the appropriate service was asked to evaluate and follow the patient for antibiotic recommendations.

Documentation of PST testing and result was done in the patient chart on a dedicated consult form. The ID fellows were responsible for updating the allergy section of the electronic medical record. Patients were also given take-home pocket cards with their test results to share with their primary care physician and future healthcare providers.

Outcome Evaluation

The primary outcome of the study was to assess the feasibility and acceptability of an ID fellow-managed PST consult service. In addition, we sought to assess the impact of the PST service on the optimization of antibiotic selection. For this, patient data were collected retrospectively by 3 study team members at the end of the first year of the program; they included demographics, details of reported penicillin allergy, PST results, clinical and microbiological indication for antibiotic use, antibiotic receipt before and after testing, length of hospital stay, and information on re-admissions. Optimization was assessed by the study investigators as changes in antibiotic therapy to narrower spectrum antibiotics, more effective therapy based on national guideline recommendations (eg, vancomycin to nafcillin for methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus [MSSA] bacteremia [13, 14]), and more cost-effective therapy based on current antibiotic costs at UMMC (eg, aztreonam vs piperacillin/tazobactam [15]).

At our institution, patients with a reported penicillin allergy are often receiving aztreonam as empiric therapy for infections with concern for involvement of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. However, the greater than 60% of local Pseudomonas isolates with aztreonam resistance and the 10-fold higher cost of aztreonam compared with alternative agents such as piperacillin/tazobactam at UMMC make this choice problematic. Therefore, we evaluated change in aggregate aztreonam use as a secondary outcome. Change in aggregate aztreonam use was evaluated as days of therapy (DOT) and defined daily dose (DDD) per 1000 patient days (PD) 1 year before and the year after PST implementation and was compared with the Mann–Whitney U test. Where indicated, clinical variables between patients were compared with the χ2 test.

Survey

Fellows completed a questionnaire regarding their knowledge of and experiences with PST at the beginning of the study and after 9 months. In addition, a survey of PST practices was sent out to all ID fellowship program directors (n = 156) in the United States; this was exempt from IRB approval based in federal regulations 45 CFR46. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the study and survey results. All statistical analysis was performed with Stata 13 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Primary Outcome: Increase in Penicillin Skin Test (PST) With Infectious Diseases Fellow-Run PST Service

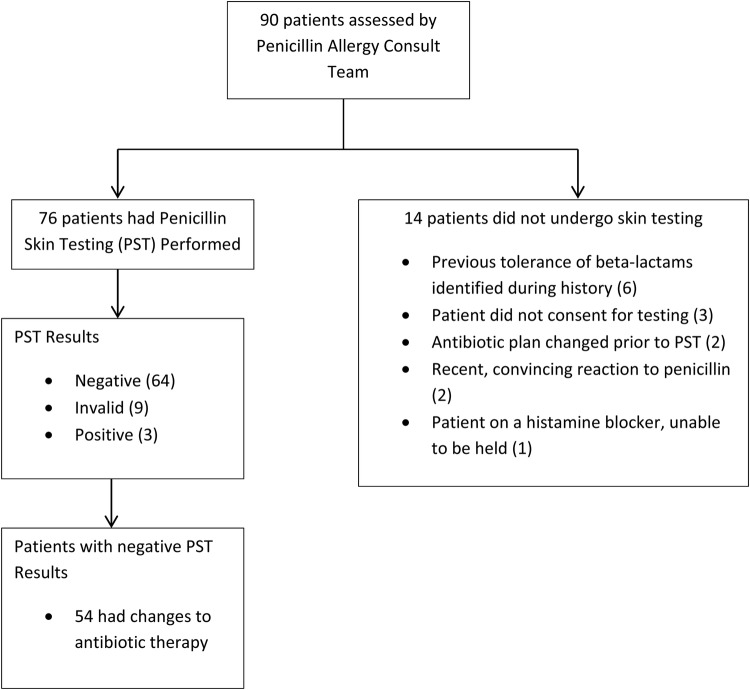

Implementation of the PST service was well received by both hospital practitioners and the ID fellows participating in the service. In the year before establishing the formal PST service, only 21 patients received penicillin skin testing. In comparison, during the first 11 months of the service, 90 patients were assessed for penicillin allergy testing and 76 patients underwent penicillin skin testing (Figure 1). The ID fellows appreciated the opportunity to learn this additional skill and reported increased comfort with assessing patient allergy, determining patient eligibility for PST, and performance of PST based on the pre- and postsurvey. In addition, all of the fellows reported on the postsurvey that they believe PST is useful to their everyday practice.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of patients assessed by penicillin allergy consult team.

The most commonly reported reaction to penicillin was hives, and the timing of the reaction was unknown in most cases (Table 1). The vast majority of patients had a negative skin test (64% or 84%), 9 (12%) had invalid tests, and 3 (4%) had positive tests. Of the valid tests, 96% were negative and 84% with a negative test had antibiotic changes. All patients with negative tests received either a 250-mg amoxicillin oral challenge or the definitive non-aztreonam β-lactam therapy. Most patients were switched to a penicillin (55%), followed by a cephalosporin (40%) or a carbapenem (5%).

Table 1.

Demographic Information of Penicillin Allergy Consult Patients (n = 90)

| Number of Patients (%) | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 28 (31) |

| Female | 62 (69) |

| Hospital Location | |

| Medical/Surgical Floors | 61 (68) |

| Intermediate Care Unit | 8 (9) |

| Intensive Care Unit | 21 (23) |

| Penicillin Allergy History | |

| Reaction | |

| Rash | 16 (18) |

| Hives | 28 (31) |

| Swelling | 11 (12) |

| Anaphylaxis | 14 (16) |

| Unknown | 21 (23) |

| Timing of Reaction | |

| Unknown | 50 (56) |

| Childhood | 17 (19) |

| >10 yrs ago | 17 (19) |

| 5–10 yrs ago | 3 (3) |

| <5 yrs ago | 3 (3) |

| Antibiotic Indication | |

| Bacteremia | 7 (8) |

| Bone/Joint Infection | 18 (20) |

| Endovascular Infection | 6 (7) |

| Gastrointestinal Infection | 15 (16) |

| Neutropenic Fever | 2 (2) |

| Pneumonia | 13 (14) |

| Skin and Soft Tissue Infection | 17 (19) |

| Sepsis of Unknown Origin | 6 (7) |

| Surgical Prophylaxis | 1 (1) |

| Urinary Tract Infection | 5 (6) |

| Testing Information | |

| Source of Penicillin Allergy Consult Request | |

| Infectious Diseases Consult Service | 72 (80) |

| Primary Care Team | 10 (11) |

| Antimicrobial Stewardship Team | 8 (9) |

| Penicillin Skin Test Performed | |

| Yes | 76 (84) |

| No | 14 (16) |

Table 2.

Penicillin Skin Test Results and Antibiotic Management

| Number of Patients (%) | |

|---|---|

| Penicillin Skin Test Results | |

| Positive | 3 (4) |

| Negative | 64 (84) |

| Invalid | 9 (12) |

| Antibiotic Management for Patients With Valid Skin Tests | |

| Change in antibiotic therapy | 54/67 (81) |

| Narrower spectrum | 34/54 (63) |

| Clinically more effective therapy | 43/54 (80) |

| More cost-effective therapy | 33/54 (61) |

| Patient's allergy list updated to reflect test results | 59 (88) |

No patient experienced any serious adverse effects related to non-aztreonam β-lactam antibiotics; 3 patients had a delayed mild rash after switch to a β-lactam (nafcillin, ertapenem, and cefepime, respectively). Of 14 patients who had negative skin tests and were re-admitted within the first year, 9 received β-lactams (5 received penicillins and 4 received a cephalosporin) during their subsequent admissions, all without complication. The allergy history in the electronic medical record was appropriately updated for 88% of patients.

Clinical Impact of Penicillin Skin Testing

Bone and joint were the most frequent sites of infection (17 of 64; 26.5%) in patients with a negative PST; 10 of the 17 patients were tested with the aim to optimize definitive antibiotic therapy. Definitive treatment for gastrointestinal (10.9%), endovascular (9.4%), and lung (7.8%) infections and empiric treatment for skin/soft tissue infections (7.8%) were the next most common indications. Eleven of 64 (17%) infections in patients with negative PST were due to MSSA, 10 due to Streptococcus spp, and 9 were due to ampicillin-sensitive Enterococcus spp.

Vancomycin was the most commonly used antibiotic in 23% of patients before PST and aztreonam in 22%. Other antibiotics used before testing included fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines, and clindamycin. Twenty patients were switched from aztreonam to alternate agents based on results of the skin test. Aztreonam use decreased from a mean ± standard deviations of 4.2 ± 2.6 DDD/1000 PD to 2.3 ± 1.3DDD/1000 PD (P = .01) and from 3.4 ± 0.9 DOT/1000 PD to 1.9 ± 0.9DOT/1000 PD (P = .0015) after PST implementation, translating into approximately $26 000 in savings per year. Overall, 63% of patients received a narrower spectrum antibiotic, 80% received more effective therapy, and 61% received more cost-effective therapy as a result of PST testing (Table 2).

A negative histamine control leading to an invalid PST occurred in 9 patients (12%), 7 of whom underwent testing while in the ICU. Intensive care unit stay was associated with an odds ratio of 23.45 (95% confidence interval, 3.57–246.13) of a negative histamine response (P < .001). However, 10 patients tested while in the ICU had a valid test result; there was no difference in age, LOS, time of consult to admission, steroid use, administration of antihistamine within 48 hours of the test, or the presence of renal insufficiency between the 7 ICU patients with an invalid histamine test and the 10 ICU patients with a valid histamine test.

Infectious Diseases Fellowship Program Director Survey

Of 156 ID fellowship program directors surveyed, 50 responded (32% response rate). Sixty percent of respondents had PST available at their institution, which was performed by allergy/immunology consult services in 94%, pharmacy in 3%, and outpatient only in 3%. The vast majority (92%) of respondents indicated that overreporting of penicillin allergy is a problem in their practice that affects antibiotic selection but listed inadequate personnel and time as the main barriers to PST implementation at their institution. Fifty-six percent of responding program directors thought their fellows could be involved in an inpatient PST service, and 70% thought that an inpatient PST service involving their ID fellows would benefit patient care and antibiotic stewardship in their hospital.

DISCUSSION

The frequent overreporting of penicillin allergy has been shown to lead to suboptimal antibiotic use and patient outcomes. The PST is a valuable tool in patients reporting penicillin allergy, but its use in inpatients, where its immediate benefit is probably highest, is often limited by resource availability. This pilot study demonstrated that a successful PST program can be successfully implemented in a large urban tertiary medical center by ID physicians with fellow support. The program had an important positive impact on patient care at our institution with 84% of patients with negative tests having their antibiotic therapy changed based on the test results. One reason for an absence of change of antibiotic therapy was that patients were tested preemptively while not receiving antibiotics (eg, a bone marrow transplant patient being tested before transplant to facilitate optimal antibiotic therapy for subsequent episodes of febrile neutropenia or antibiotic prophylaxis). For other patients, antibiotic therapy was not adjusted due to a change in circumstances after testing (eg, maintaining the patient on linezolid posttesting to facilitate intravenous to oral therapy conversions for discharge).

Two surveys from the Emerging Infections Network plus our own survey of the ID fellowship program directors indicate that appropriate elimination of penicillin allergy from a patient's record can impact antimicrobial stewardship at their own institutions [9, 16]. Infectious diseases physicians are frequently consulted to evaluate patients reporting a penicillin allergy and play an important role in the management of these patients. Exclusion of antibiotic allergies can lead to more appropriate antibiotic selection, improved antibiotic stewardship, and safer administration of antibiotics [16]. Limitations identified to incorporating PST most often cited were inadequate personnel and inadequate time. A PST service incorporating ID fellow trainees not only offers personnel to administer test but also a valuable learning experience to the trainees. In addition to the national survey, we performed an interval survey of the UMMC fellows before the start of the program and on completion of the program. Most fellows reported increased confidence in their ability to assess a patient's allergy history, to determine when a PST is indicated for a patient, and in their ability to perform the PST. All fellows surveyed agreed that PST was useful to their practice.

Allergy skin testing has traditionally been done exclusively by allergists, generally in the outpatient setting. A survey assessing how allergists vs nonallergists manage patients with a penicillin allergy found a difference in the willingness of nonallergists to administer penicillins after a negative skin test [17]. Physicians without exposure to allergy skin testing are unfamiliar and uncomfortable with requesting, administering, and interpreting test results, and they may be less likely to use those results in subsequent clinical decisions. A study of the management of patients reporting a penicillin allergy in a large Canadian tertiary-care academic hospital without allergists on staff found that allergy documentation was poor and patients with alleged penicillin allergies had increased antibiotic-related costs [18]. Although the ideal scenario would be to have allergists available to assess penicillin allergies for inpatients, in reality, the number of certified allergists is not sufficient to manage this commonly reported allergy with approximately 5900 board certified allergists in the United States who mostly practice in an outpatient setting [19]. The PST is a relatively straightforward test that can be administered by physicians, nurses, and, in some states, medical assistants and pharmacists. Novel successful models of PST have been demonstrated in the emergency department (ED) setting by ED physicians [20] and in a tertiary care center by pharmacists [21]. It is important to increase access to this test by using nonallergist practitioners with proper training when allergists are not available. One advantage of an ID-managed inpatient PST program is that ID providers are often the ones who first recognize the need for testing and can quickly perform the test and act on the results. In addition, by providing this training to ID fellows, upon graduation they are well positioned to implement PST in their future practices, expanding overall access to testing. Inpatient PST testing can be counted towards antibiotic stewardship and antibiotic cost-savings activities. In one institution, the annual savings from successful transitions to β-lactam agents after negative PSTs was $82 000 [8]. In the outpatient setting, up to 9 Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes are applied to 1 PST based on number of pricks/injections, with a total reimbursement of approximately $180 000 with an additional CPT code for an oral challenge.

In our study, of the patients with valid tests, 96% tested negative, similar to reports in the literature [22], and led to antibiotic changes in most of the patients. These changes included narrower, more clinically effective, and/or more cost-effective antibiotics. Establishment of an ID fellow-managed program increased access to testing, allowed for optimization of antibiotic therapy for an increased number of patients, and helped to train ID specialists who can bring PST experience to their future practices.

Two high-impact areas for antibiotic optimization in penicillin allergic patients are invasive MSSA and enterococcal infections. Our study demonstrated multiple patients with MSSA bacteremia with antibiotic changes from vancomycin to nafcillin or cefazolin after negative PST, which has repeatedly been shown to be superior therapy [13, 14]. Likewise, improved outcomes are seen for patients with Enterococcus faecalis endocarditis changed from vancomycin, daptomycin, or linezolid to ampicillin [24, 25]. In a recent study, a model was published simulating 3 strategies for patients with MSSA bacteremia and a reported penicillin allergy: (1) no allergy evaluation and patient receives vancomycin; (2) allergy history-guided treatment—if history excludes anaphylaxis, give cefazolin; and (3) allergy evaluation with PST—if negative, give cefazolin. The model demonstrated improvements in rates of MSSA cure, recurrence, and death in patients with negative PST and subsequent cefazolin therapy (84.5%/8.9%/6.6% with negative PST and cefazolin vs 67.3%/14.8%/17.9% with vancomycin) [23]. Although improvements were best in the negative PST group, they were only marginally better than the allergy history-guided treatment group, which had 83.4% cure, 9.3% recurrence, and 7.3% death. This reinforces the importance of thorough allergy histories, which was part of our penicillin allergy service because we often found that PST was not needed when a thorough allergy history was done. Of note, PST cannot fully assess cephalosporin or carbapenem allergy, and use of these agents after penicillin skin testing would have to be guided by physician's discretion.

Another area where we found testing to be beneficial is before bone marrow or solid organ transplant to remove the allergy from patient records in anticipation of future antibiotic needs. Although the patients tested did not require antibiotics at the time, clarification of their allergies before transplant allowed for better antibiotic options in the setting of febrile neutropenia or infection posttransplant and more optimal surgical prophylaxis per our institutional guidelines for the solid organ transplants.

One major challenge in this PST program was the rate of invalid tests due to a negative histamine control (12%), which has been reported to be as high as 20% in the literature [26]. A recent analysis of 52 cases of patients with a negative histamine response in the absence of antihistamine (H1 receptor blocker) therapy for 72 hours before testing identified ICU status regardless of age to be associated with a negative histamine response. In addition, systemic corticosteroids, older age, and receipt of an H2 receptor blocker (eg, ranitidine, famotidine) were associated with a lack of histamine response [27]. Our results support the observation that ICU admission might increase the risk of a negative histamine test. This could be a consideration when evaluating patients for skin testing. In our experience, attempts to retest patients with invalid tests have added significant material and time resource requirements.

Another challenge in our study was to ensure the optimal documentation of test results. Because this was a real-world implementation study, it was noted during the retrospective chart review that the patient allergy history in the chart was updated for only 88% of tested patients. For optimal impact of a PST program, communication of results to future providers is of the utmost importance. Therefore, patients were given a take-home wallet card with their test results and were advised to share it with their outpatient providers or at any future hospitalizations. However, suboptimal documentation in the medical charts of our hospital or other hospitals and clinics may still impede future antibiotic therapy. Shared access to electronic medical records across the healthcare continuum may improve this in the future.

Our study has several limitations. The study was observational in nature and we could not control for patient selection bias. In addition, a formal cost analysis of antibiotic savings was not completed. However, aztreonam use declined over the course of the intervention and suggested cost savings for our hospital—although we cannot formally exclude other reasons for the decline. In addition, our program may not be generalizable to ID programs that train fewer fellows or hospitals that have no fellowship program and hence lack the necessary personnel resources.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, we evaluated a durable model for inpatient penicillin skin testing managed by ID fellows. This model could increase access to PST at institutions without adequate access to allergists while also providing an important educational experience to ID trainees.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the infectious disease fellows from the University of Maryland for their continued efforts in our penicillin skin testing initiatives.

Financial support. This work was supported by an education grant from ALK-Abello, Inc. E. L. H. and J. T. B. received support for travel from ALK-Abello to present the results of this work.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest.

References

- 1.Lee CE, Zembower TR, Fotis MA et al. The incidence of antimicrobial allergies in hospitalized patients: implications regarding prescribing patterns and emerging bacterial resistance. Arch Intern Med 2000; 160:2819–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Charneski L, Deshpande G, Smith SW. Impact of an antimicrobial allergy label in the medical record on clinical outcomes in hospitalized patients. Pharmacotherapy 2011; 31:742–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.MacLaughlin EJ, Saseen JJ, Malone DC. Costs of beta-lactam allergies: selection and costs of antibiotics for patients with a reported beta-lactam allergy. Arch Fam Med 2000; 9:722–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Unger NR, Gauthier TP, Cheung LW. Penicillin skin testing: potential implications for antimicrobial stewardship. Pharmacotherapy 2013; 33:856–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.PREPEN [product information] Round Rock, TX: ALK-Abello, Inc.; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sogn DD, Evans R, Sheperd GM et al. Results of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases collaborative clinical trial to test the predictive value of skin testing with major and minor penicillin derivatives in hospitalized adults. Arch Intern Med 1992; 152:1025–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harris AD, Sauberman L, Kabbash L et al. Penicillin skin testing: a way to optimize antibiotic utilization. Am J Med 1999; 107:166–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rimawi RH, Cook PP, Gooch M et al. The impact of penicillin skin testing on clinical practice and antimicrobial stewardship. J Hosp Med 2013; 8:341–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abbo LM, Beekmann SE, Hooton TM et al. Management of antimicrobial allergies by infectious diseases physicians. JAMA Intern Med 2013; 173:1376–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chandrasekar P, Havlichek D, Johnson LB. Infectious diseases subspecialty: declining demand challenges and opportunities. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 59:1593–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chandrasekar PH. Bad news to worse news: 2015 infectious diseases fellowship match results. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 60:1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The Match. Match Results Statistics. Medical Specialties Matching Program-2015. Appointment Year 2016, pp 16. Available at: www.nrmp.org Accessed 29 April 2016.

- 13.Schweizer ML, Furuno JP, Harris AD et al. Comparative effectiveness of nafcillin or cefazolin versus vancomycin in methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. BMC Infect Dis 2011; 11:279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim SH, Kim KH, Kim HB et al. Outcome of vancomycin treatment in patients with methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2008; 52:192–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Red Book Online [database online]. Greenwood Village, CO: Truven Health Analytics, Inc. Updated periodically. Available at: https://www.micromedexsolutions.com/micromedex2/librarian/ssl/true. Accessed 20 November 2015.

- 16.Infectious Diseases Society of America Emerging Infections Network Report for Query “Antibiotic Allergy Practices”, 2015. Available at: http://ein.idsociety.org/. Accessed 6 August 2016.

- 17.Suetrong N, Klaewsongkram J. The differences and similarities between allergists and non-allergists for penicillin allergy management. J Allergy (Cairo) 2014; doi:10.1155/2014/214183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Picard M, Begin P, Bouchard H et al. Treatment of patients with a history of penicillin allergy in a large tertiary-care academic hospital. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2013; 1:252–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.American Board of Allergy and Immunology. Diplomate Statistics as of October 2015. Available at: https://www.abai.org/statistics_diplomates.asp Accessed 26 November 2015.

- 20.Raja AS, Lindsell CJ, Bernstein JA et al. The use of penicillin skin testing to assess the prevalence of penicillin allergy in an emergency department setting. Ann Emerg Med 2009; 54:72–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wall GC, Peters L, Leaders CB, Wille JA. Pharmacist-managed service providing penicillin allergy skin tests. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2004; 61:1271–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salkind AR, Cuddy PG, Foxworth JW. Is this patient allergic to penicillin? JAMA 2001; 285:2498–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blumenthal KG, Parker RA, Shenoy ES, Walensky RP. Improving clinical outcomes in patients with methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia and reported penicillin allergy. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61:741–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ceron I, Munoz P, Marin M et al. Efficacy of daptomycin in the treatment of enterococcal endocarditis: a 5 year comparison with conventional therapy. J Antimicro Chemother 2014; 69:1669–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baddour LM, Wilson WR, Bayer AS et al. Infective endocarditis in adults: diagnosis, antimicrobial therapy, and management of complications. Circulation 2015; 132:1–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin E, Saxon A, Ridel M. Penicillin allergy: value of including amoxicillin as a determinant in penicillin skin testing. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2010; 152:313–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geng B, Thakor A, Clayton E et al. Factors associated with negative histamine control for penicillin allergy skin testing in the inpatient setting. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2015; 115:33–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]