Abstract

Mucopolysaccharidosis type II (MPS II, Hunter syndrome) is an X-linked genetic disorder caused by a deficiency of iduronate 2-sulfatase (IDS), and missense mutations comprising about 30% of the mutations responsible for MPS II result in heterogeneous phenotypes ranging from the severe to the attenuated form. To elucidate the basis of MPS II from the structural viewpoint, we built structural models of the wild type and mutant IDS proteins resulting from 131 missense mutations (phenotypes: 67 severe and 64 attenuated), and analyzed the influence of each amino acid substitution on the IDS structure by calculating the accessible surface area, the number of atoms affected and the root-mean-square distance. The results revealed that the amino acid substitutions causing MPS II were widely spread over the enzyme molecule and that the structural changes of the enzyme protein were generally larger in the severe group than in the attenuated one. Coloring of the atoms influenced by different amino acid substitutions at the same residue showed that the structural changes influenced the disease progression. Based on these data, we constructed a database of IDS mutations as to the structures of mutant IDS proteins.

Introduction

Iduronate 2-sulfatase (IDS, EC 3.1.6.13) is a lysosomal enzyme that catalyses the hydrolysis of sulfated esters at the non-reducing-terminal iduronic acids in the glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) heparan sulfate and dermatan sulfate. A deficiency of IDS activity results in systemic accumulation of GAGs, leading to a rare metabolic disease, mucopolysaccharidosis type II (MPS II, OMIM 309900), which is also known as Hunter syndrome [1]. Patients with MPS II typically exhibit systemic manifestations including a short stature, a specific facial appearance, dysostosis multiplex, a thick skin, inguinal hernia, hepatosplenomegaly, hearing difficulty, an ophthalmic problem, a respiratory defect, heart disease, and occasional neurologic involvement. However, this disease exhibits a wide range of clinical phenotypes from the “severe form” with progressive clinical deterioration to the “attenuated form” without mental retardation.

Enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) involving recombinant human IDS is approved in many countries for treatment of MPS II patients. As recent studies demonstrated that ERT improved the manifestations of MPS II, especially when it was started at an early age [2–5], an early diagnosis and clinical phenotype determination are becoming more and more important for predicting the prognoses of patients and a proper therapeutic plan.

The IDS gene is located at the Xq27/28 boundary [6], and contains nine exons spread over 24 kb [7,8]. It has been reported that 2.3 kb-IDS cDNA encodes a polypeptide of 550 amino acids showing high homology with the sulfatase protein family [8,9]. The synthesized IDS requires post-translational modification including removal of the signal sequence peptide, glycosylation, phosphorylation, proteolysis, and conversion of C84 to the catalytic formylglycine: the 76 kDa precursor is processed through intermediates to the 55 kDa and 45 kDa mature forms [10]. So far, at least 530 genetic mutations responsible for MPS II have been identified, and it is known that gross alterations lead to the severe form. However, missense mutations comprising about 30% of the MPS II mutations result in heterogeneous phenotypes ranging from the severe to the attenuated form.

As to human IDS, no crystal structure has been reported, and a few structural models have been constructed by means of homology modeling using crystal structure information of other sulfatases including arylsulfatase A and arylsulfatase B as templates [11–14]. In those studies, some missense mutations were found to be localized on the predicted IDS structure and the effects of amino acid substitutions were discussed. But the number of mutations discussed was very small.

In this study, we built a new structural model of human IDS by means of the homology modeling and molecular dynamics methods, and predicted structural changes in IDS caused by 131 amino acid substitutions responsible for MPS II, and examined the relationship between the mutant IDS structures and the respective clinical phenotypes.

Methods

Missense mutations in the IDS gene

In this study, we analyzed 131 missense mutations in the IDS gene for which the MPS II phenotypes have been clearly described (67 severe and 64 attenuated). These missense mutations, the respective phenotypes, and the references are summarized in Table 1, and other missense mutations in the IDS gene that were excluded in this analysis are summarized in S1 Table.

Table 1. IDS mutations, phenotypes, references, and structural characteristics for mutant IDS proteins.

| Mutation | Phenotype* | Numbers of affected atoms | RMSD | ASA | Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main chain | Side chain | Active Site | (Å) | (Å2) | |||

| p.D45N | Attenuated | 30 | 40 | 13 | 0.04 | 1 | Vafiadaki (1998) Arch Dis Child 79:237 |

| p.R48P | Attenuated | 81 | 107 | 0 | 0.086 | 30.6 | Sukegawa (1995) Hum Mutat 6:136 |

| p.Y54D | Severe | 24 | 30 | 0 | 0.039 | 126.8 | Karsten (1998) Hum Genet 103:732 |

| p.S61P | Attenuated | 80 | 67 | 0 | 0.071 | 2 | Sohn (2012) Clin Genet 81:185 |

| p.N63D | Attenuated | 4 | 15 | 0 | 0.022 | 53.5 | Karsten (1998) Hum Genet 103:732 |

| p.N63K | Severe | 28 | 43 | 0 | 0.038 | 53.5 | Chang (2005) Hum Genet 116:160 |

| p.L67P | Severe | 24 | 24 | 0 | 0.045 | 3.2 | Zhang (2011) PLoS One 6:e22951 |

| p.A68E | Severe | 188 | 205 | 0 | 0.125 | 2.1 | Schroeder (1994) Hum Mutat 4:128 |

| p.S71R | Severe | 105 | 109 | 0 | 0.085 | 0.2 | Li (1999) J Med Genet 36:21 |

| p.S71N | Attenuated | 30 | 29 | 0 | 0.04 | 0.2 | Froissart (1998) Clin Genet 53:362 |

| p.L72P | Severe | 64 | 83 | 0 | 0.07 | 1.2 | Zhang (2011) PLoS One 6:e22951 |

| p.A79E | Attenuated | 153 | 167 | 22 | 0.097 | 0 | Karsten (1998) Hum Genet 103:732 |

| p.Q80K | Severe | 203 | 199 | 7 | 0.103 | 5.2 | Gucev (2011) Prilozi 32:187 |

| p.P86R | Severe | 281 | 325 | 9 | 0.171 | 0 | Hopwood (1993) Hum Mutat 2:435 |

| p.P86L | Severe | 114 | 118 | 6 | 0.096 | 0 | Vafiadaki (1998) Arch Dis Child 79:237 |

| p.S87N | Attenuated | 10 | 10 | 2 | 0.025 | 0.4 | Popowska (1995) Hum Mutat 5:97 |

| p.R88C | Severe | 189 | 222 | 29 | 0.108 | 0.4 | Karsten (1998) Hum Genet 103:732 |

| p.R88G | Severe | 159 | 212 | 23 | 0.097 | 0.4 | Froissart (1998) Clin Genet 53:362 |

| p.R88H | Severe | 23 | 37 | 16 | 0.032 | 0.4 | Karsten (1998) Hum Genet 103:732 |

| p.R88L | Severe | 27 | 39 | 5 | 0.04 | 0.4 | Karsten (1998) Hum Genet 103:732 |

| p.R88P | Severe | 40 | 63 | 16 | 0.051 | 0.4 | Villani (2000) Biochim Biophys Acta 1501: 71 |

| p.L92P | Severe | 14 | 9 | 0 | 0.028 | 5.4 | Popowska (1995) Hum Mutat 5:97 |

| p.G94D | Attenuated | 111 | 107 | 0 | 0.098 | 0 | Hopwood (1993) Hum Mutat 2:435 |

| p.R95G | Attenuated | 126 | 147 | 0 | 0.086 | 34 | Goldenfum (1996) Hum Mutat 7:76 |

| p.R95T | Attenuated | 87 | 97 | 0 | 0.071 | 34 | Moreira da Silva (2001) Clin Genet 60:316 |

| p.P97R | Severe | 514 | 542 | 25 | 0.229 | 3.6 | Sohn (2012) Clin Genet 81:185 |

| p.L102R | Attenuated | 129 | 142 | 8 | 0.127 | 0 | Karsten (1998) Hum Genet 103:732 |

| p.Y108C | Attenuated | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.002 | 131 | Rathmann (1996) Am J Hum Genet 59:1202 |

| p.Y108S | Attenuated | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.002 | 131 | Zhang (2011) PLoS One 6:e22951 |

| p.W109R | Severe | 76 | 98 | 0 | 0.054 | 110.3 | Chistiakov (2014) J Genet Genomics 41:197 |

| p.N115Y | Attenuated | 56 | 45 | 0 | 0.093 | 25.3 | Vafiadaki (1998) Arch Dis Child 79:237 |

| p.S117Y | Severe | 134 | 127 | 0 | 0.094 | 34.6 | Kim (2003) Hum Mutat 21:449 |

| p.Q121R | Severe | 221 | 241 | 9 | 0.146 | 24.6 | Froissart (1998) Clin Genet 53:362 |

| p.E125V | Attenuated | 6 | 2 | 0 | 0.015 | 127.2 | Rathmann (1996) Am J Hum Genet 59:1202 |

| p.T130N | Attenuated | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.006 | 56.9 | Boyadjiev (2012) Mol Genet Metab 105:S22 |

| p.T130I | Attenuated | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.002 | 56.9 | Zhang (2011) PLoS One 6:e22951 |

| p.S132W | Severe | 328 | 340 | 8 | 0.192 | 44.8 | Jonsson (1995) Am J Hum Genet 56:597 |

| p.G134R | Severe | 146 | 171 | 9 | 0.11 | 1.4 | Rathmann (1996) Am J Hum Genet 59:1202 |

| p.G134E | Attenuated | 61 | 78 | 9 | 0.1 | 1.4 | Amartino (2014) Mol Genet Metab Rep 1:401 |

| p.K135R | Attenuated | 54 | 41 | 0 | 0.047 | 13.3 | Hopwood (1993) Hum Mutat 2:435 |

| p.K135N | Attenuated | 28 | 38 | 0 | 0.033 | 13.3 | Popowska (1995) Hum Mutat 5:97 |

| p.H138D | Attenuated | 355 | 365 | 21 | 0.155 | 13 | Froissart (1998) Clin Genet 53:362 |

| p.H138R | Severe | 52 | 37 | 0 | 0.049 | 13 | Chang (2005) Hum Genet 116:160 |

| p.G140R | Attenuated | 244 | 296 | 15 | 0.18 | 3.5 | Kato (2005) J Hum Genet 50:395 |

| p.S142F | Severe | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.002 | 84.8 | Chistiakov (2014) J Genet Genomics 41:197 |

| p.S142Y | Severe | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.003 | 84.8 | Amartino (2014) Mol Genet Metab Rep 1:401 |

| p.S143F | Severe | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0.003 | 77.3 | Vallence (1999) hum mut mutation in brief#233 online |

| p.D148V | Severe | 71 | 70 | 3 | 0.072 | 105.2 | Keeratichamroen (2008) J Inherit Metab Dis 31S2:S303 |

| p.P157S | Severe | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.007 | 62.6 | Amartino (2014) Mol Genet Metab Rep 1:401 |

| p.H159P | Severe | 64 | 69 | 4 | 0.086 | 46.6 | Karsten (1998) Hum Genet 103:732 |

| p.C171R | Attenuated | 15 | 17 | 0 | 0.029 | 23.4 | Kato (2005) J Hum Genet 50:395 |

| p.N181I | Attenuated | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.009 | 121.9 | Moreira da Silva (2001) Clin Genet 60:316 |

| p.L182P | Attenuated | 45 | 43 | 0 | 0.048 | 60.6 | Isogai (1998) J Inherit Metab Dis 21:60 |

| p.C184F | Attenuated | 267 | 281 | 0 | 0.137 | 25.8 | Rathmann (1996) Am J Hum Genet 59:1202 |

| p.L196S | Attenuated | 3 | 21 | 0 | 0.019 | 5 | Jonsson (1995) Am J Hum Genet 56:597 |

| p.D198N | Severe | 53 | 99 | 0 | 0.062 | 0.6 | Amartino (2014) Mol Genet Metab Rep 1:401 |

| p.D198G | Attenuated | 225 | 250 | 9 | 0.111 | 0.6 | Karsten (1998) Hum Genet 103:732 |

| p.A205P | Attenuated | 11 | 9 | 0 | 0.032 | 2 | Goldenfum (1996) Hum Mutat 7:76 |

| p.T214M | Severe | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.003 | 82.4 | Amartino (2014) Mol Genet Metab Rep 1:401 |

| p.L221P | Attenuated | 37 | 46 | 0 | 0.059 | 6.4 | Hopwood (1993) Hum Mutat 2:435 |

| p.G224A | Severe | 1 | 9 | 0 | 0.037 | 3.3 | Keeratichamroen (2008) J Inherit Metab Dis 31S2:S303 |

| p.G224E | Severe | 40 | 56 | 4 | 0.065 | 3.3 | Karsten (1998) Hum Genet 103:732 |

| p.Y225D | Attenuated | 98 | 124 | 3 | 0.081 | 3.4 | Sukegawa (1993) 3rd Inter Sympo on MPS, Essen |

| p.K227M | Attenuated | 5 | 19 | 0 | 0.018 | 3.6 | Isogai (1998) J Inherit Metab Dis 21:60 |

| p.K227Q | Severe | 7 | 27 | 0 | 0.025 | 3.6 | Hopwood (1993) Hum Mutat 2:435 |

| p.P228L | Attenuated | 161 | 197 | 18 | 0.116 | 0.4 | Vafiadaki (1998) Arch Dis Child 79:237 |

| p.P228A | Attenuated | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.004 | 0.4 | Sohn (2012) Clin Genet 81:185 |

| p.P228Q | Severe | 198 | 223 | 12 | 0.111 | 0.4 | Amartino (2014) Mol Genet Metab Rep 1:401 |

| p.P228T | Severe | 20 | 19 | 1 | 0.039 | 0.4 | Gort (1998) J Inherit Metab Dis 21:655 |

| p.H229Y | Severe | 14 | 25 | 4 | 0.027 | 15 | Jonsson (1995) Am J Hum Genet 56:597 |

| p.P231L | Attenuated | 9 | 15 | 0 | 0.019 | 26.9 | Gort (1998) J Inherit Metab Dis 21:655 |

| p.R233G | Attenuated | 9 | 17 | 0 | 0.021 | 85 | Chistiakov (2014) J Genet Genomics 41:197 |

| p.K236N | Attenuated | 19 | 26 | 0 | 0.027 | 73.9 | Gucev (2011) Prilozi 32:187 |

| p.P261A | Attenuated | 47 | 43 | 0 | 0.077 | 107.3 | Sohn (2012) Clin Genet 81:185 |

| p.N265I | Attenuated | 41 | 57 | 0 | 0.044 | 0.5 | Filocamo (2001) Hum Mutat 18:164 |

| p.N265K | Severe | 127 | 148 | 0 | 0.077 | 0.5 | Chistiakov (2014) J Genet Genomics 41:197 |

| p.P266R | Severe | 105 | 140 | 0 | 0.086 | 6 | Vafiadaki (1998) Arch Dis Child 79:237 |

| p.W267C | Attenuated | 54 | 54 | 0 | 0.057 | 82.9 | Chang (2005) Hum Genet 116:160 |

| p.Q293H | Attenuated | 91 | 110 | 0 | 0.091 | 0.6 | Schroeder (1994) Hum Mutat 4:128 |

| p.K295I | Severe | 7 | 16 | 0 | 0.015 | 71.2 | Amartino (2014) Mol Genet Metab Rep 1:401 |

| p.S299I | Attenuated | 141 | 172 | 0 | 0.088 | 0 | Kim (2003) Hum Mutat 21:449 |

| p.S305P | Attenuated | 63 | 67 | 0 | 0.054 | 30.7 | Brusius-Facchin (2014) Mol Genet Metab 111:133 |

| p.D308N | Attenuated | 15 | 31 | 0 | 0.03 | 9 | Isogai (1998) J Inherit Metab Dis 21:60 |

| p.D308E | Attenuated | 43 | 42 | 0 | 0.054 | 9 | Gort (1998) J Inherit Metab Dis 21:655 |

| p.T309A | Severe | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.003 | 55.2 | Gort (1998) J Inherit Metab Dis 21:655 |

| p.G312D | Attenuated | 23 | 25 | 0 | 0.034 | 5.5 | Amartino (2014) Mol Genet Metab Rep 1:401 |

| p.S333L | Severe | 67 | 73 | 21 | 0.072 | 0 | Vafiadaki (1998) Arch Dis Child 79:237 |

| p.D334N | Attenuated | 22 | 23 | 2 | 0.034 | 0.8 | Froissart (1998) Clin Genet 53:362 |

| p.D334G | Severe | 52 | 52 | 14 | 0.07 | 0.8 | Li (1996) J Inherit Metab Dis 19:93 |

| p.H335R | Attenuated | 42 | 49 | 20 | 0.049 | 0.6 | Froissart (1998) Clin Genet 53:362 |

| p.G336E | Severe | 235 | 291 | 30 | 0.159 | 0 | Froissart (1998) Clin Genet 53:362 |

| p.G336V | Severe | 97 | 137 | 23 | 0.11 | 0 | Kato(2005) J Hum Genet 50:395 |

| p.W337R | Attenuated | 84 | 111 | 18 | 0.057 | 0.2 | Sukegawa (1995) Hum Mutat 6:136 |

| p.L339R | Severe | 37 | 69 | 1 | 0.042 | 3.8 | Froissart (1998) Clin Genet 53:362 |

| p.L339P | Severe | 33 | 52 | 0 | 0.059 | 3.8 | Amartino (2014) Mol Genet Metab Rep 1:401 |

| p.G340D | Attenuated | 20 | 17 | 0 | 0.024 | 4.2 | Karsten (1998) Hum Genet 103:732 |

| p.E341K | Severe | 348 | 458 | 23 | 0.16 | 21 | Vallence (1999) hum mut mutation in brief#233 online |

| p.H342Y | Attenuated | 27 | 31 | 0 | 0.035 | 5 | Vallence (1999) hum mut mutation in brief#233 online |

| p.W345R | Severe | 25 | 32 | 1 | 0.03 | 0.4 | Amartino (2014) Mol Genet Metab Rep 1:401 |

| p.W345K | Attenuated | 22 | 29 | 1 | 0.032 | 0.4 | Popowska (1995) Hum Mutat 5:97 |

| p.A346D | Attenuated | 100 | 115 | 15 | 0.083 | 0 | Olsen (1996) Hum Genet 97:198 |

| p.K347E | Severe | 249 | 251 | 18 | 0.109 | 0.8 | Chang (2005) Hum Genet 116:160 |

| p.K347T | Severe | 90 | 97 | 16 | 0.072 | 0.8 | Villani (1997) Hum Mutat 10:71 |

| p.S349I | Severe | 70 | 95 | 0 | 0.072 | 0.2 | Gort (1998) J Inherit Metab Dis 21:655 |

| p.P358R | Severe | 320 | 323 | 8 | 0.123 | 2 | Jonsson (1995) Am J Hum Genet 56:597 |

| p.L403R | Severe | 375 | 423 | 35 | 0.13 | 5.5 | Froissart (1998) Clin Genet 53:362 |

| p.L410P | Attenuated | 21 | 28 | 0 | 0.043 | 0 | Ben Simon-Schiff (1994) Hum Mutat 4:263 |

| p.C422Y | Attenuated | 312 | 311 | 9 | 0.197 | 0 | Gort (1998) J Inherit Metab Dis 21:655 |

| p.C422G | Attenuated | 6 | 14 | 0 | 0.017 | 0 | Hopwood (1993) Hum Mutat 2:435 |

| p.C432R | Attenuated | 33 | 35 | 0 | 0.043 | 113.1 | Lualdi (2006) Biochim Biophys Acta 1762:478 |

| p.C432Y | Severe | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.002 | 113.1 | Karsten (1998) Hum Genet 103:732 |

| p.Q465P | Severe | 85 | 114 | 3 | 0.09 | 13.8 | Hartog (1999) Hum Mutat 14:87 |

| p.P467L | Severe | 92 | 109 | 0 | 0.101 | 0.6 | Moreira da Silva (2001) Clin Genet 60:316 |

| p.R468Q | Severe | 366 | 421 | 17 | 0.161 | 0 | Vafiadaki (1998) Arch Dis Child 79:237 |

| p.R468G | Severe | 61 | 100 | 0 | 0.063 | 0 | Hopwood (1993) Hum Mutat 2:435 |

| p.R468L | Severe | 82 | 117 | 0 | 0.06 | 0 | Sukegawa (1995) Hum Mutat 6:136 |

| p.R468P | Severe | 289 | 301 | 0 | 0.13 | 0 | Charoenwattanasatien (2012) Biochem Genet 50:990 |

| p.P469H | Attenuated | 96 | 118 | 4 | 0.063 | 0.2 | Jonsson (1995) Am J Hum Genet 56:597 |

| p.D478G | Attenuated | 27 | 32 | 0 | 0.042 | 54 | Schroeder (1994) Hum Mutat 4:128 |

| p.D478Y | Severe | 20 | 35 | 0 | 0.029 | 54 | Karsten (1998) Hum Genet 103:732 |

| p.P480R | Severe | 116 | 145 | 0 | 0.088 | 42.9 | Froissart (1998) Clin Genet 53:362 |

| p.P480Q | Attenuated | 39 | 47 | 0 | 0.07 | 42.9 | Froissart (1998) Clin Genet 53:362 |

| p.P480L | Attenuated | 10 | 16 | 0 | 0.041 | 42.9 | Froissart (1998) Clin Genet 53:362 |

| p.I485R | Severe | 170 | 236 | 0 | 0.141 | 155.6 | Vafiadaki (1998) Arch Dis Child 79:237 |

| p.I485K | Severe | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.005 | 155.6 | Vafiadaki (1998) Arch Dis Child 79:237 |

| p.G489D | Severe | 62 | 68 | 0 | 0.064 | 1.8 | Chang (2005) Hum Genet 116: 160 |

| p.Y490S | Attenuated | 6 | 7 | 0 | 0.024 | 74.7 | Froissart (1998) Clin Genet 53:362 |

| p.S491F | Severe | 135 | 167 | 0 | 0.081 | 0.4 | Sohn (2012) Clin Genet 81:185 |

| p.W502C | Severe | 23 | 20 | 0 | 0.03 | 2.2 | Vafiadaki (1998) Arch Dis Child 79:237 |

| p.L522P | Severe | 55 | 65 | 0 | 0.063 | 0.8 | Sohn (2012) Clin Genet 81:185 |

| p.Y523C | Attenuated | 12 | 17 | 0 | 0.023 | 8.4 | Jonsson (1995) Am J Hum Genet 56:597 |

*Description of the phenotypes is according to the original papers.

Structural modeling of the human wild type IDS protein

Because no IDS crystal structure has been reported, we built a model of human IDS using homology modeling server I-TASSER (zhanglab.ccmb.med.umich.edu/ I-TASSER/) [15]. To take protein structure fluctuations into consideration, we conducted molecular dynamics calculations using Gromacs (version 5.0.5) [16]. In the simulation, we used the AMBER99sb force field and SPC/E water models. At first, we performed structure optimization using the steepest-descent method. Then, we carried out equilibration in two phases (NVT and NPT ensemble). As the production run, we performed 10ns MD simulation using Parrinello-Rahman pressure coupling and V-rescale temperature simulation. In order to obtain a representative structure, we used the simulated annealing method.

Structural modeling of mutant IDS proteins and calculation of the numbers of atoms influenced by amino acid substitutions responsible for MPS II

Structural models of mutant human IDS proteins responsible for MPS II were built by means of homology modeling using the wild type IDS protein model as a template. For that purpose, we used molecular modeling software TINKER [17], and energy minimization was performed, the root-mean-square graduate value being set at 0.05 kcal/mol・Å. Then, each mutant model was superimposed on the wild type IDS structure based on the Cα atoms by the least-square-mean fitting method. We defined that an atom was influenced by an amino acid substitution when the position of the atom in a mutant IDS protein differed from that in the wild type one by more than the cut-off distance (0.15 Å) based on the total root-mean-square distance (RMSD), as described previously [18]. We calculated the numbers of influenced atoms in the main chain (the protein backbone: alpha carbon atoms linked to the amino group, the carboxyl one, and hydrogen atoms of the molecule) and the side chain (variable components linked to the alpha carbons of the molecule), and in the active site (D45, D46, C84, K135, and D334). Then, average numbers of influenced atoms were calculated for the severe MPS II group and the attenuated one.

Determination of the RMSD values of all atoms in the mutant IDS proteins

To determine the influence of each amino acid substitution on the total conformational change in IDS, the RMSD values of all atoms in the mutant IDS proteins were calculated according to the standard method [19]. Then, average RMSD values were calculated for the severe group and the attenuated one.

Determination of the accessible surface area (ASA) of the amino acid residues of the IDS protein

The ASA of each amino acid residue in the structure of the wild type IDS was calculated using Stride [20] to determine the location of the residue in the IDS molecule. Then, the average ASA values of the residues for which substitutions had been identified in the severe group and the attenuated one were calculated.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis to determine the differences in the numbers of influenced atoms, the RMSD, and the ASA values between the severe MPS II group and the attenuated one was performed by means of Welch’s t-test, and it was taken that there was a significant difference if p< 0.05.

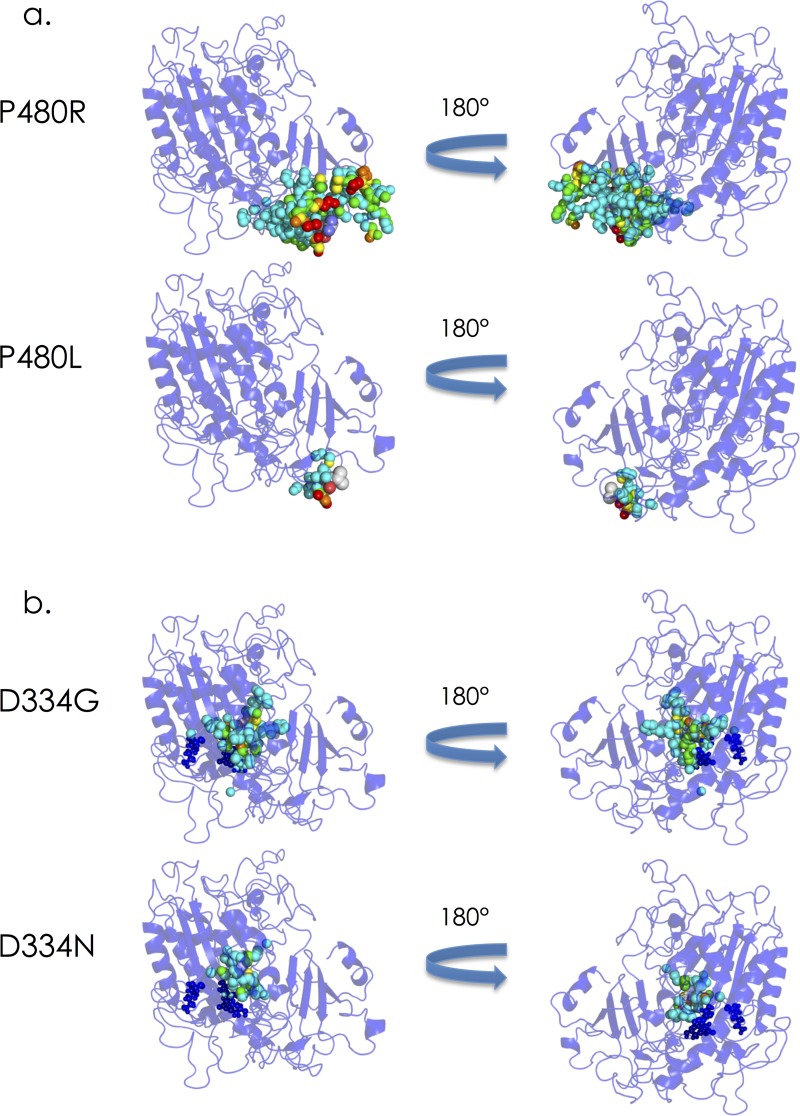

Coloring of the atoms influenced by different amino acid substitutions at the same residue on IDS

Coloring of the influenced atoms in the three-dimensional structure of IDS was performed for amino acid substitutions including P480R (phenotype: severe), P480L (phenotype: attenuated), D334G (phenotype: severe), and D334N (phenotype: attenuated) as representatives, based on the distance between the wild type and mutant to determine the influence of the amino acid substitutions geographically and semi-quantitatively according to the method previously described [18].

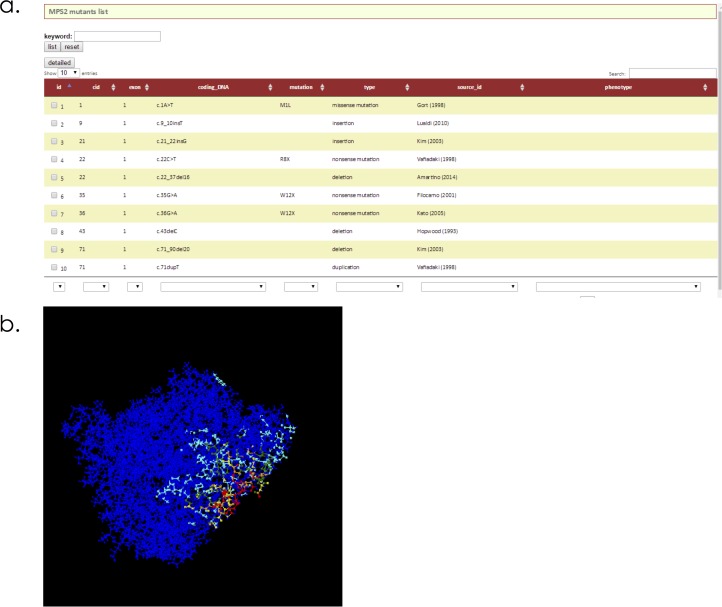

Construction of a database including genotypes, clinical phenotypes, references and mutant IDS structures in MPS II

In order to help researchers and clinicians who study MPS II, we built a database including the genotypes, clinical phenotypes, references, and structures of mutant IDSs, according to the method described previously [21].

Results

Structural model of the human IDS protein and locations of the amino acid residues associated with MPS II

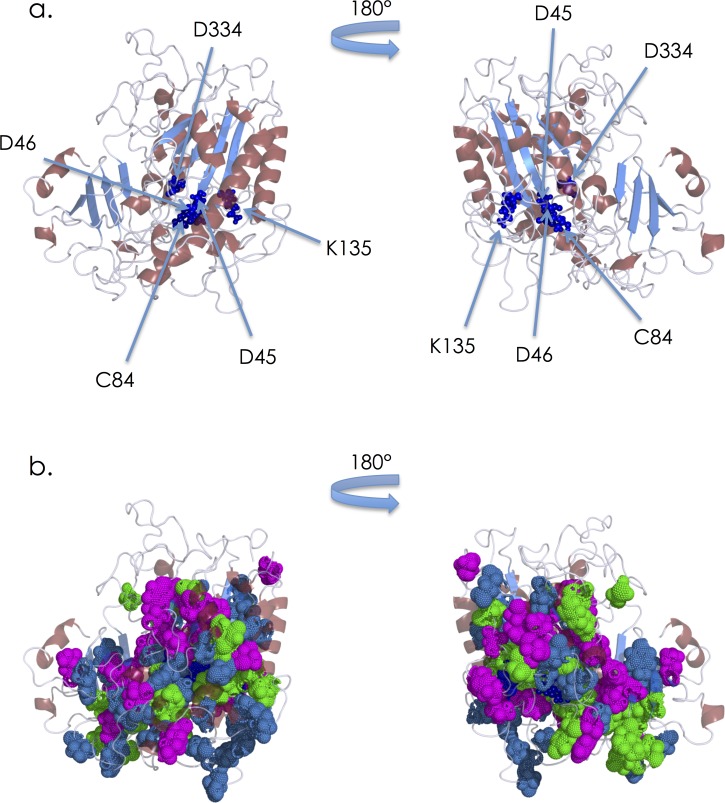

A homology modeling server was used to construct a structural model of the wild type IDS protein. For this calculation, several known structures were used as templates (pdb id: 2w8s, 2vqr, 3b5q, and 2quz). The results of the homology modeling revealed that IDS consists of alpha/beta folds, and that it contains two antiparallel beta-sheets (each sheet has 4 beta strands) with alpha helixes around them. The active site is located in the loop region near the N-terminal antiparallel beta-strand, and the D45, D46, C84, K135 and D334 residues comprising the putative active site [14] are indicated (Fig 1A). Then, to elucidate the relationship between the locations of the amino acid substitutions associated with MPS II and the respective phenotypes, we identified the positions of the residues in the wild type IDS protein structure (Fig 1B). The locations of the amino acid residues involved in the substitutions were widely spread over the enzyme molecule.

Fig 1.

Predicted structure of human IDS (a), and positions of amino acid residues where substitutions responsible for MPS II have been identified (b). The backbone is displayed as a ribbon model. (a) IDS is colored according to the secondary structure. Helices are colored red, sheets blue, and loops gray. The residues comprising the putative active site (D45, D46, C84, K135, and D334) are presented as small dark blue spheres. (b) The residues involved in substitutions responsible for MPS II are presented as spheres (severe: magenta, attenuated: blue, and both: green).

Numbers of atoms influenced by amino acid substitutions associated with MPS II

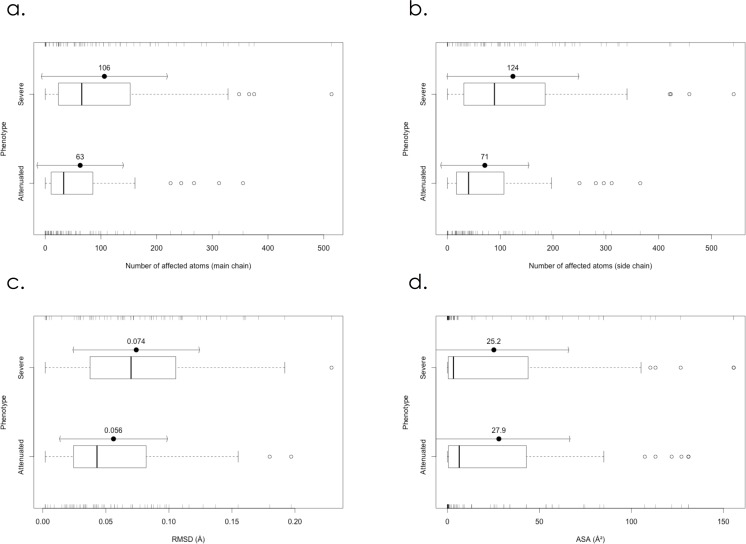

Then, we constructed structural models of the mutant IDS proteins and calculated the number of atoms influenced by the amino acid substitution for each mutant model. The results are summarized in Table 1. In the severe phenotypic group, the average values (± standard deviation, SD) for the influenced atoms in the main chain and the side chain regarding the amino acid substitutions were 106 (± 113) and 124 (± 125), respectively. In particular, 42 of the 67 severe cases (63%) had 50 atoms or more influenced in the main chain. On the other hand, in the attenuated group, the averages (± SD) of the influenced atoms in the main chain and side chain were 63 (± 78) and 71 (± 84), respectively. Notably, regarding the main chain atoms, 39 of the 64 of the attenuated cases (61%) had 49 atoms or less affected. Fig 2 shows the means ± SD and boxplots of the influenced atoms of the main chain (Fig 2A) and the side chain (Fig 2B) in the severe MPS II group and the attenuated one. Welch’s t-test revealed that there was a significant difference in the numbers of influenced atoms in both the main chain and the side chain (p<0.05) between the severe and attenuated groups. These results indicate that the structural changes caused by the amino acid substitutions responsible for severe MPS II were generally larger than those for attenuated MPS II. As to the influence of amino acid substitutions on the active site, the atoms of the residues comprising the putative active site were affected in 31 of the 67 severe cases (46%) and 17 of the 64 attenuated ones (27%).

Fig 2.

Boxplots of numbers of atoms affected by amino acid substitutions in the main chain (a) and the side chain (b), RMSD values between mutant and wild type IDS proteins (c), and ASA of amino acid residues where substitutions responsible for MPS II occur (d). Severe: Severe group. Attenuated: Attenuated group.

RMSD values between mutant IDS proteins and the wild type

To clarify the total structural change caused by each amino acid substitution, the RMSD value between the mutant IDS protein and the wild type was calculated, and the results are summarized in Table 1. The means ± SD and boxplots of RMSD values for the severe MPS II group and attenuated one are shown in Fig 2C. The average RMSD values (± SD) for the severe and attenuated groups were 0.074 (± 0.050) and 0.056 (± 0.043) Å, respectively. The Welch’s t-test showed that there was a significant difference in RMSD between the severe MPS II group and the attenuated one (p<0.05). These results indicate that structural changes in the severe MPS II group were larger than those in the attenuated one.

ASA of the amino acid residues associated with MPS II mutations

To identify the locations of the residues associated with MPS II mutations in the IDS protein, the ASA values of the residues in the wild type structure were calculated and the results are summarized in Table 1. Fig 2D shows the means ± SD and boxplots of ASA for the severe group and the attenuated one. In the severe MPS II group, the average ASA value (± SD) was 25.2 (± 40.8) Å2. On the other hand, in the attenuated MPS II group, it was 27.9 (± 38.7) Å2. The results of the Welch’s t-test (p> 0.05) showed that there was no significant difference between the two groups.

Effects of different substitutions at the same residue on the IDS structure and coloring of atoms affected in the molecule

We next examined the effects of different substitutions at the same residue on the structural changes in the molecule and expression of the clinical phenotypes. There are at least 12 residues in the amino acid sequence of IDS at which different substitutions lead to different phenotypes (Table 1). For seven of those residues (N63, S71, G134, K227, N265, D334, and D480), the RMSD value and the number of affected atoms for the severe group were larger than those for the attenuated one. On the other hand, for 3 residues (H138, D198, and C432), the RMSD value and the number of affected atoms for the attenuated group were larger than those for the severe one. As to the other 2 residues (P228 and W345), it could not be determined for which phenotype the RMSD value and the number of affected atoms were larger than the other. Then, we examined the structural changes in IDS caused by P480R (phenotype: severe), P480L (phenotype: attenuated), D334G (phenotype: severe), and D334N (phenotype: attenuated) by means of coloring of the atoms affected. P480 is located near the molecular surface, and far from the active site. P480R is thought to cause a large structural change around the substituted residue, although it does not affect the active site, leading to the severe phenotype. The structural change caused by P480L is small and the influenced atoms are limited, leading to the attenuated phenotype (Fig 3A). On the other hand, D334 is a residue comprising the active site, and the D334G and D334N substitutions are both thought to directly affect the structure of the active site. The structural change in the former is larger than that in the latter, leading to the difference in phenotype (Fig 3B)

Fig 3.

Coloring of the atoms influenced by amino acid substitutions, (a) P480R and P480L, and (b) D334G and D334N, in the three-dimensional structure of IDS. The backbone of IDS is shown as a blue ribbon model. The influenced atoms are presented as spheres. The colors of the influenced atoms show the distances between the wild type and mutant proteins as follows: 0.15Å ≤ cyan < 0.30 Å, 0.30 Å ≤ green < 0.45Å, 0.45 Å ≤ yellow < 0.60Å, 0.60 Å ≤ orange< 0.75Å, and 0.75Å ≤ red.

Database of the genotypes, clinical phenotypes, references and mutant IDS structures in MPS II

We developed a database including the genotypes, clinical phenotypes, references and mutant IDS structures responsible for MPS II (mps2-database.org) (Fig 4A). The database provides readers with information on 530 MPS II mutations, which include 161 missense ones. The database is equipped with several tools. A text search tool is provided for searching the given text in selected fields of the database. Furthermore, using the control table option, users can search for MPS II mutations connected with specific phenotypes. A structural viewer is included in the database, which allows users to display the three-dimensional structures of the molecules using Jmol (Fig 4B). Furthermore, users can use many options for visualizing the structures of mutant IDS proteins.

Fig 4.

The list of MPS II gene mutations (a), and coloring of a mutant IDS protein with p.A68E (b) in the database (mps2-database.org).

Discussion

Structural information on defective IDS proteins is important to elucidate the pathogenesis of MPS II, and is also useful for understanding the basis of the disease in each patient and for preparing a proper therapeutic plan for him or her.

So far, several structural models of the wild type IDS have been reported [11–14]. Unfortunately, they have not been registered in the Protein Data Bank (pdb), and thus we could not precisely compare our new model with them. However, as far as we examined the figures in their reports, it seems that there are no large differences in the whole structure between their models and ours, but there are small differences between them, i.e., in the loop regions of the molecule.

Regarding the locations of residues involved in amino acid substitutions, Kato et al. examined eight cases (phenotypes: 4 severe and 4 attenuated), and reported that the mutations found in the severe phenotype probably undergo direct interactions with the active site residues or break the hydrophobic core region of IDS, whereas residues of the missense mutations found in the attenuated phenotype were located in the peripheral region [13]. But our study, in which 131 missense mutations (phenotypes: 67 severe and 64 attenuated) were analyzed, revealed that there was essentially no difference in the localization of amino acid substitutions between the severe group and the attenuated one (Figs 1B and 2D).

In order to examine structural changes caused by the amino acid substitutions we calculated the numbers of atoms affected and the RMSD values. The results revealed that structural changes in the severe group were generally larger than those in the attenuated one (Fig 2A, 2B and 2C).

We examined structural changes caused by different substitutions at the same residue in the amino acid sequence of IDS and the phenotypes. Furthermore, structural changes caused by P480R, P480L, D334G, and D334N were examined as representative cases by coloring of the atoms affected in IDS. The results revealed that the structural changes influenced the disease progression.

A lot of expression studies have been performed, and the results revealed that the “attenuated” mutants expressed the precursor and small amounts of the mature IDS, resulting in residual enzyme activity, although the “severe” mutants expressed the precursor but no mature IDS, resulting in almost completely deficient enzyme activity [14,22–25]. Considering these findings, the majority of the “severe” missense mutants cause large structural changes and defects of the molecular folding, leading to rapid degradation and/or insufficient processing. On the other hand, the “attenuated” missense mutants generally cause small structural changes and moderate folding defects, leading to partial degradation of the enzyme protein and residual activity. Some mutants may directly affect the active site, leading to a decrease in enzyme activity according to the degree of the structural changes.

Finally, we built a database of IDS gene mutations responsible for MPS II, clinical phenotypes, references, and predicted structures of mutant IDSs. This database can be accessed via the Internet, being user-friendly.

In conclusion, we constructed structural models of the wild type and mutant IDS proteins by means of the latest homology modeling techniques, and showed the correlation between the structural changes and clinical phenotypes. This database based on the results of a structural study will help investigators and clinicians who study MPS II.

Supporting Information

(XLSX)

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Fumie Yokoyama (Level-Five, Tokyo) for her collection of the mutation data. This work was supported by the Japan Society for Promotion of Science (ID: 15K090, HS).

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Japan Society for Promotion of Science (ID: 15K090, HS).

References

- 1.Neufeld EF, Muenzer J. The mucopolysaccharidosis In: Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Sly WS, Valle D, editors. The Metabolic and Molecular Basis of Inherited Disease, Vol. Ⅲ, 8th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001. pp. 3421–3452. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tajima G, Sakura N, Kosuga M, Okuyama T, Kobayashi M. Effects of idursulfase enzyme replacement therapy for mucopolysaccharidosis type II when started in early infancy: comparison in two siblings. Mol Genet Metab. 2013; 108:172–177. 10.1016/j.ymgme.2012.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sohn YB, Cho SY, Lee J, Kwun Y, Huh R, Jin DK. Safety and efficacy of enzyme replacement therapy with idursulfase beta in children aged younger than 6 years with Hunter syndrome. Mol Genet Metab. 2015; 114:156–160. 10.1016/j.ymgme.2014.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guffon N, Heron B, Chabrol B, Feillet F, Montauban V, Valayannopoulos V. Diagnosis, quality of life, and treatment of patients with Hunter syndrome in the French healthcare system: a retrospective observational study. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2015; 10:43 10.1186/s13023-015-0259-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parini R, Rigoldi M, Tedesco L, Boffi L, Brambilla A, Bertoletti S, et al. Enzymatic replacement therapy for Hunter disease: Up to 9 years experience with 17 patients. Mol Genet Metab Rep. 2015; 3:65–74. 10.1016/j.ymgmr.2015.03.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson PJ, Suthers GK, Callen DF, Baker E, Nelson PV, Cooper A, et al. Frequent deletions at Xq28 indicate genetic heterogeneity in Hunter syndrome. Hum Genet. 1991; 86:505–508. 10.1007/bf00194643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flomen RH, Green EP, Green PM, Bentley DR, Giannelli F. Determination of the organisation of coding sequences within the iduronate sulphate sulphatase (IDS) gene. Hum Mol Genet. 1993; 2:5–10. 10.1093/hmg/2.1.5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilson PJ, Meaney CA, Hopwood JJ, Morris CP. Sequence of the human iduronate 2-sulfatase (IDS) gene. Genomics. 1993; 17:773–775. 10.1006/geno.1993.1406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilson PJ, Morris CP, Anson DS, Occhiodoro T, Bielicki J, Clements PR, et al. Hunter syndrome: isolation of an iduronate-2-sulfatase cDNA clone and analysis of patient DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990; 87:8531–8535. 10.1073/pnas.87.21.8531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmidt B, Selmer T, Ingendoh A, von Figura K. A novel amino acid modification in sulfatases that is defective in multiple sulfatase deficiency. Cell. 1995; 82:271–278. 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90314-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim CH, Hwang HZ, Song SM, Paik KH, Kwon EK, Moon KB, et al. Mutational spectrum of the iduronate 2-sulfatase gene in 25 unrelated Korean Hunter syndrome patients: Identification of 13 novel mutations. Hum Mutat. 2003; 21:449–450. 10.1002/humu.9128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parkinson-Lawrence E, Turner C, Hopwood J, Brooks D. Analysis of normal and mutant iduronate-2-sulphatase conformation. Biochem J. 2005; 386:395–400. 10.1042/BJ20040739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kato T, Kato Z, Kuratsubo I, Tanaka N, Ishigami T, Kajihara J, et al. Mutational and structural analysis of Japanese patients with mucopolysaccharidosis type II. J Hum Genet. 2005; 50:395–402. 10.1007/s10038-005-0266-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sukegawa-Hayasaka K, Kato Z, Nakamura H, Tomatsu S, Fukao T, Kuwata K, et al. Effect of Hunter disease (mucopolysaccharidosis type II) mutations on molecular phenotypes of iduronate-2-sulfatase: enzymatic activity, protein processing and structural analysis. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2006; 29:755–761. 10.1007/s10545-006-0440-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Y. I-TASSER server for protein 3D structure prediction. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008; 9:40 10.1186/1471-2105-9-40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hess B, Kutzner C, van der Spoel D, Lindahl E. GROMACS 4: algorithms for highly efficient, load-balanced, and scalable molecular simulation. J Chem Theory Comput. 2008; 4:435–447. 10.1021/ct700301q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kundrot CE, Ponder JW, Richards FM. Algorithms for calculating excluded volume and its derivatives as a function of molecular conformation and their use in energy minimization. J Comput Chem. 1991; 12:402–409. 10.1002/jcc.540120314 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsuzawa F, Aikawa S, Doi H, Okumiya T, Sakuraba H. Fabry disease: correlation between structural changes in α-galactosidase, and clinical and biochemical phenotype. Hum Genet. 2005; 117:317–328. 10.1007/s00439-005-1300-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kabsh W. A solution for the best rotation to relate two sets of vectors. Acta Crystallogr. 1976; A32:827 10.1107/s0567739476001873 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frishman D, Argos P Knowledge-based protein secondary structure assignment. Proteins. 1995; 23:566–579. 10.1002/prot.340230412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saito S, Ohno K, Sakuraba H. Fabry-database.org: database of the clinical phenotypes, genotypes and mutant α-galactosidase A structures in Fabry disease. J Hum Genet. 2011; 56:467–468. 10.1038/jhg.2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Millat G, Froissart R, Cudry S, Bonnet V, Maire I, Bozon D. COS cell expression studies of P86L, P86R, P480L and P480Q Hunter's disease-causing mutations. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998; 1406:214–218. 10.1016/s0925-4439(97)00096-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Charoenwattanasatien R, Cairns JRK, Keeratichamroen S, Sawangareetrakul P, Tanpaiboon P, Wattanasirichaigoon D, et al. Decreasing activity and altered protein processing of human iduronate-2-sulfatase mutations demonstrated by expression in COS7 cells. Biochem Genet. 2012; 50:990–997. 10.1007/s10528-012-9538-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chang JH, Lin SP, Lin SC, Tseng KL, Li CL, Chuang CK, et al. Expression studies of mutations underlying Taiwanese Hunter syndrome (mucopolysaccharidosis type II). Hum Genet. 2005; 116:160–166. 10.1007/s00439-004-1234-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sukegawa K, Tomatsu S, Fukao T, Iwata H, Song XQ, Yamada Y, et al. Mucopolysaccharidosis type II (Hunter disease): identification and characterization of eight point mutations in the iduronate-2-sulfatase gene in Japanese patients. Hum Mutat. 1995; 6:136–143. 10.1002/humu.1380060206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(XLSX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.