Chromosomes, the longest molecular fiber that stores genetic information in eukaryotic cells, must be orderly packaged during mitosis for their proper segregation into daughter cells. Although the morphological changes of chromosomes during mitosis have been described in detail, how mitosis progression programs the transformation of seemingly amorphous and loose interphase chromosomes into highly characteristic mitotic chromosomes remains a classical problem in cell biology. Strikingly, the chromosomal morphology and the karyotypes in mitotic cells of a given organism are highly reproducible. This reproducibility indicates that chromosome packaging during mitosis follows an intrinsically defined pathway of chromatin folding. This pathway is likely governed by a mechanism that “precisely” determines the chromatin-folding regions. In addition, this pathway has to be coupled with and controlled by the temporal progression of the cell cycle. Thus, the cell-cycle-regulated chromatin folding is a central problem that needs to be explained in order to truly understand chromosomal packaging. To date, the nature of this internal logic is still largely unknown.

Numerous studies have focused on chromosomal organization, especially of metaphase and interphase chromosomes. Specific models were proposed for the structure of mitotic chromosomes. For example, one of the models assumed an organizational role of a protein-based scaffold (Adolph et al., 1977; Paulson and Laemmli 1977; Maeshima and Laemmli 2003). However, the existence of such a scaffold in chromosomal organization was questioned in more studies, which suggest instead a network organization of chromosomes (Poirier and Marko, 2002). In addition, a hierarchical swirling model was proposed to describe the pathway of chromatin folding in mitotic chromosomes (Kireeva et al., 2004). The concept of chromosome territories, which emphasizes the non-random positioning of chromosomes in the nuclear space, has been emerging as a consensus for the organization of interphase chromosomes (Cremer and Cremer, 2010). As to the internal organization of interphase chromosomes, the chromatin network model was proposed (Dehghani et al., 2005). These and other models mainly focus on describing the possible chromatin organization in chromosomes at a specific stage of the cell cycle. In other words, they focus on snapshots of the chromosomes, leaving the mechanism of the cell-cycle-coupled progressive packaging and unpackaging largely unexplained.

In 2011, I proposed a DNA-repeat-based general principle for chromatin folding and organization (Tang, 2011a). According to this principle, homologous DNA repeats undergo repeat pairing (RP) to form compact repeat assemblies (RAs). As such, repetitive elements function as matchmakers (crosslinkers) that direct chromatin-chromatin interactions to specify chromatin folding. In other words, RP guides site-directed chromatin folding. RP is a concept that was proposed to describe the interaction or association of homologous repeats in the cell (Tang, 2011a). No assumption was made on the involvement of strict Watson-Crick pairing in RP. The idea of RP was further sustained by a recent report of the spatial clustering of repeats in the same families, revealed by analysis of published data from chromosomal conformation capture (3C) studies (Cournac et al., 2016). Based on the principle of RP and empirical data, I postulated the skeletal structure of mitotic and interphase chromosomes (Tang, 2011b, 2012). Here, I wish to consider the implications of the principle of RP, which appears to be compatible with published data on the progressive packaging of chromosomes during mitosis. I will attempt to explain how an interphase chromosome is progressively condensed into a mitotic chromosome during the cell cycle and how the metaphase chromosome is transformed into the decondensed interphase chromosome.

The model

The theory for chromosome packaging during mitosis that I put forward here involves the following basic assumption: cation-regulated RP (i.e., RA formation) is the driving force for chromosome packaging during mitosis. The empirical evidence for this assumption will be given latter. The organization of interphase chromosomes is the starting point of the chromosome packaging during mitosis. Furthermore, the interphase chromosomes’ organization primes mitotic packaging. For the sake of simplicity, I subjectively divide the process of mitotic chromosome packaging into the following four stages:

-

1)

Initiation of packaging (prophase). Two important events happen at this stage. One is that the concentration of cations, including divalent cations (e.g., Ca2+ & Mg2+), starts increasing. The other event is nuclear envelope breakdown (NEB). Cation increase triggers the formation of new RPs and RAs, and NEB facilitates RA formation by eliminating steric constrains created by chromosomes’ attachments to the envelope.

-

2)

Progression of packaging (prophase-prometaphase-metaphase). This stage is characterized by sequential RP and RA formation, which directly causes chromatin folding and packaging in an orderly fashion. The end result is the formation of the chromoaxis, chromonodes and chromatin loops (including loop supercoils) (Tang, 2011b).

-

3)

End of packaging (metaphase). At metaphase, when cation concentrations are at their highest, RP occurs between high-threshold and low-density repeats. At this stage, non-homologous chromatins may also aggregate by electrostatic interaction. This chromatin collapse, which is not mediated by RP, marks the final stage of the formation of highly compact metaphase chromosomes.

-

4)

Reversal of packaging (metaphase –telophase-interphase). Cations (such as Ca2+ and Mg2+) decrease when mitosis progresses toward completion and heads into interphase. This sequentially reverses the packaging process outlined above starting with the dissociation of non-RP-based chromatin aggregates, followed by disruption of late-formed RAs first and then early-formed RAs. Some RAs remain stable in interphase, and they are the organizers of interphase chromosomes.

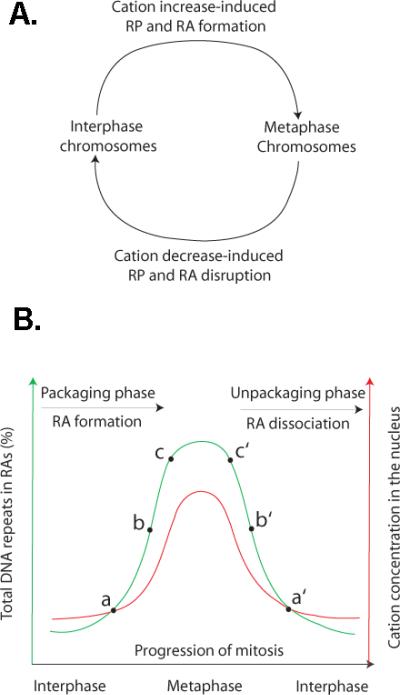

The central idea of the model is that cation dynamics regulate the interaction of DNA repeats (i.e., the formation of RAs) and consequently the condensation and decondensation of the chromosomes during mitosis (Fig. 1A). When cation concentrations are increasing, it favors the formation of RAs. During this time, chromosomes condensation occurs. When cation concentrations are decreasing, which favors the disruption of RPs and thus the dissociation of RAs, condensed chromosomes undergo the process of decondensation. In the following sections, I shall describe the key elements of the model in more detail and provide supporting evidence.

Fig. 1. A cation-regulated and RA-mediated potential mechanism for chromosome organization during mitosis.

A: A model of cation-regulated and RP/RA-mediated chromosome packaging and unpackaging during mitosis. B: Postulated relationship between cation dynamics (red lines) and RA dynamics (green lines) during cell cycles (black arrows). The key point that I intend to illustrate here is that the packaging and unpackaging of chromosomes during mitosis are driven by cation-regulated formation and disruption of a set of RAs, respectively. For example, a and a′ (or b and b′, or c and c′) are corresponding chromosomal organizations speculated to form during the packaging or unpackaging phase, respectively. They have similar topologies, which are organized by a similar set of RPs, at different stages of the cell cycle with similar concentrations of cations.

RP, RA and chromosome packaging during the cell cycle

Models of the repetitive-DNA-organized structure of mitotic and interphase chromosomes have been proposed previously (Tang, 2011b, 2012). Those models are proposed snapshots of the organization of dynamic chromosomes at specific stages of the cell cycle. Extending these models, I want to describe the process of chromosome condensation and decondensation (i.e., the dynamic transition from one state of chromosome organization to another) during mitosis. The crucial idea in this line of thinking is the assumption of the dynamic formation (or disruption) of RPs as the driving force of the transition.

I propose that, during the process of chromosome packaging (i.e., interphase → metaphase), more and more DNA repeats are progressively assembled into RAs via RPs. Consequently, chromatins are gradually folded (packaged) into mitotic chromosomes (Fig. 1B). It is important to emphasize that this RP-guided and cell cycle-coupled chromatin folding is highly, if not completely, precise. According to the CORE (chromosome organization by repetitive elements) theory (Tang, 2011a), DNA repeats mark the locations where chromatins are folded (and crosslinked with other chromatin regions). Thus, the distribution pattern of DNA repeats in the linear chromatin is expected to determine the folding pathway of this chromatin. I suggest that the RP-directed precision of chromatin folding is the key molecular basis for the reproducibility of chromosome packaging in different cells or different cell divisions. At the late stage of packaging, when RPs are largely completed, the chromatin can be further condensed via folding-independent chromatin collapse. The late-stage collapse-mediated chromosome packaging presumably occurs when high concentrations of cations largely neutralize the electro-repelling force in chromatins (see below). The collapse-mediated packaging is not directed by RP and probably occurs non-specifically, although it is influenced by and is largely constrained by the previous RP-directed packaging.

On the other hand, during the process of chromosome decondensation (i.e., metaphase → interphase), many RAs gradually dissociate due to disruption of RPs. As a result of the RP disruption, the packaged mitotic chromosomes are progressively decondensed (unpackaged) (Fig. 1B). It is reasonable to conceive that the process of unpackaging is a reversal of the packaging process. In other words, the packaging and unpackaging of chromosomes during the progression of the cell cycle are two processes that are probably inversely symmetric to one another. The repeats that are assembled into RAs at the early stages of chromosome packaging will dissociate from their paring partners at late stages of unpackaging, while the repeats that are assembled into RAs during the late stages of chromosome packaging will dissociate at the early stages of unpackaging (Fig. 1B).

An important feature of RP-mediated chromatin packaging during cell cycles is its reversibility. The same RA can be formed at one time but dissociate at another. The formation or disruption of the same RA is expected to have a definite impact on the organization of chromatins in the chromosomes. It is a tempting idea that the reversibility of RPs is the molecular basis of the reversibility of chromosome morphology.

Repeats in a given family (especially interspersed repeats) may undergo RP at different periods during chromosome packaging. Some members may complete RP earlier than others. Thus, different members of repeats in the same family likely have distinct roles during the progression of chromosome packaging. On the other hand, chromosome packaging is the result of coordinated RPs of different repeat families. At a given stage of packaging, repeats in multiple families may undergo RPs, with particular families being the dominant groups..

It is not clear how formation of a specific set of RPs is determined at a specific stage of chromosome packaging. In theory, any one repeat may interact with many other members of the family. For orderly packaging of chromatins, it is critical for a specific repeat to interact with designated homologous sequences. Spatial and topological restrictions may constrain the available partners. Prior RPs can guide subsequent RPs, by creating or removing constrains for a given repeat.

Although many details are currently incomplete, if the conceptual model presented here is correct, the nature of chromosomal packaging or unpackaging during the progression of the cell cycles is programmed by the formation or disruption of RPs (or RAs), respectively.

Cation-regulated RP during mitosis

Another crucial idea in the proposed model is that dynamic cation concentrations during cell cycles regulate the formation and disruption of RPs. Cation concentration increase favors RA formation, while a decrease in cations promotes RA dissociation. In addition, RA formation is expected to be critically regulated by the local concentration of involved repeats. It is self-evident that the local concentration of tandem repeats is much higher than that of dispersed repeats, and therefore, tandem repeats are among the early sequences that undergo RPs to form tandem repeat assemblies (TRAs). This may explain why some satellite repeats (e.g., satellite repeats at centromeres) are in heterochromatins during interphase. In contrast to tandem repeats, the local concentration of dispersed repeats is relatively low and may change dynamically. By altering the spatial distribution of associated chromatins, preceding RPs can change the local concentration of dispersed repeats and thus program subsequent RPs. Some dispersed repeats that were spatially distant before can be brought closer for RPs. Therefore, the local concentration of specific repeats is also dynamic. In this way, RPs underlying progressive chromosome packaging are sequentially programmed by mitosis-regulated cation changes and dynamic local concentrations of repeats.

Several lines of evidence indicate an important role of cations in regulating chromosomal packaging. In vitro studies clearly shown that cation increase in physiological ranges promotes the aggregation of nucleosomes (de Frutos et al., 2001). Cation-promoted nucleosome association can be easily explained by the neutralization of the negative charge on DNA. Importantly, mitotic chromosomes in cells can be induced to undergo reversible morphological changes by altering cation concentrations (Cole, 1967; Hudson et al., 2003). The reversibility of the morphology suggests that cation changes cause non-random chromatin folding (packaging), which likely results from induced alteration of the biophysical properties of chromatins. How this cation-regulated reversible packaging is achieved is remained unclear. I speculate that cation concentrations control this process by regulating the formation or disruption of RPs. Several studies from different laboratories have demonstrated the homology-dependent paring of double stranded DNA (dsDNA) (Inoue et al., 2007; Baldwin et al., 2008; Danilowicz et al., 2009). Inoue et al. (2007) observed that Mg2+ promotes self-assembly of dsDNA under protein-free conditions (Inoue et al., 2007). It is important to note that these studies were performed with naked DNA rather than with chromatin on histone cores. The cation conditions for the association of dsDNA, single-stranded DNA (ssDNA), nucleosomes or chromatins appear to be very similar (de Frutos et al., 2001; Raspaud et al., 1999; Lu et al., 2006), indicating that the presence of histones may not greatly alter the self-association property of DNA. Consistent with this notion, more recent work shows that chromatins (or nucleosomes) with homologous DNAs prefer to self-assemble (Cherstvy and Teif, 2013; Nishikawa and Ohyama, 2013).

Roles of cations in chromosome condensation have been established both in cells and in vitro (Cole, 1967; Bojanowski and Ingber, 1998; Strick et al., 2001; Hudson et al., 2003; Lu et al., 2006). Cations neutralize negative charges on DNA phosphate backbones and probably establish salt bridges between interacting repeats. From interphase to mitosis, cation concentrations, especially Ca2+ and Mg2+, increase in chromatins (Strick et al., 2001). It was speculated that Mg2+ is a trigger of the condensation-decondensation transition of chromosomes during mitosis (Jerzmanowski and Staron, 1980). Cations are known to regulate the compact state of tandem repeats in heterochromatins (Horvath and Hörz, 1981; Zhang and Horz, 1982). The Ca2+ concentration is higher on the AT-rich axis of mitotic chromosomes, probably binding to the minor groove of the AT-rich sequence (Strick et al., 2001a). As I suggested previously (Tang, 2011b), the AT-rich axis mainly consists of tandem repeats. Importantly, in vitro studies indicate that divalent cations (e.g., Mg2+) selectively stimulate self-association of DNA fragments (Inoue et al., 2007). If cations similarly affect the aggregation of naked DNA or DNA on histone cores as proposed (Raspaud, Chaperon et al. 1999; de Frutos, Raspaud et al. 2001), this observation would suggest that cations may preferentially promote DNA-repeat-mediated chromatin-chromatin interaction. As such, cation concentration increase during mitosis is thought to stimulate the formation of new RPs and stabilize preexisting RPs. Ca2+ binds satellite repeats more strongly than bulk chromatins (Zhang and Horz, 1982). While Ca2+ is enriched on the axis, the Mg2+ concentration is higher mainly in the halo of mitotic chromosomes (Strick et al., 2001a). According to the chromosomal skeleton model, assemblies of tandem repeats form the longitudinal axis while the assemblies of dispersed repeats organize chromatins around the axis (Tang, 2011). The differential distribution of Ca2+ along the axis and Mg2+ in the halo indicate that Ca2+ may preferentially regulate RPs of tandem repeats, whereas Mg2+ preferentially controls RPs of dispersed repeats. Although less data are available in the context of chromosome condensation during cell cycles, other cations such as Mn2+, which can interact with both DNA phosphates and bases (Teif and Bohinc 2011), may also contribute to repeat-mediated chromatin folding, given their reported activity in inducing DNA condensation (Cherstvy et al., 2002). Mn2+ was reported to be able to support yeast cell cycle progression in place of Ca2+ (Loukin and Kung, 1995), indicating that Mn2+ may replace the role of Ca2+ in chromosome condensation.

Although relatively low concentrations of cations are speculated to promote RPs, high concentrations may cause aggregation of spatially nearby non-homologous chromatins and lead to the formation of highly compact chromosomes. This non-specific chromatin collapse probably occurs mainly during the late stage of chromosome packaging when a RA-organized chromoskeleton has formed and thus would not dramatically affect large-scale morphology of mitotic chromosomes. Therefore, according to this postulated scheme, the progressive increase of cations leads to a progressive packaging of chromosomes that is guided by the sequential formation of RPs; whereas progressive decrease of cations causes a progressive unpackaging of chromosomes guided by the sequential dissociation of RPs (Fig. 1B). The cation-regulated sequential formation (or disruption) of RPs proposed here can explain nicely the reversibility of chromosome morphology during mitosis and cation-regulated reversible changes of mitotic chromosomes (Cole, 1967; Hudson et al., 2003). It should be noted that a possible mechanism of reentrant chromatin condensation was proposed (Teif and Bohinc, 2011). According to the reentrant condensation mechanism, chromatins undergo condensation as cations increase but will proceed to decondensation if the increase of cations goes over a certain limit. In this context, it will be interesting to check the RP behavior follows the reentrant effect.

As shown by Strick et al. and others (Cameron et al., 1979; Strick et al., 2001), there is in general a rise of cations in the nucleus during the transition from interphase to metaphase, and the reversal of cation concentration during the transition from the mitosis to interphase. Sporadic observations were reported regarding the changes of cation concentration in the nucleus during mitosis, but information in this aspect remain rudimental and a solid general conclusion is hard to be made based on the available information because of different cells or methods of cation measurements used (Cameron et al., 1979; Kendall et al., 1985; Wroblewski et al., 1983). In this aspect, the studies by Strick et al. (2001) provide informative insights into the correlation between the change of cation concentration (especially Ca2+ and Mg2+) in chromosomes and chromosomal condensation during mitosis. In interphase Indian muntjac (IM) deer fibroblasts, while Ca2+ was found throughout the cytosol, with possible accumulation in ER and Golgi complex, it was reduced in the nucleus. In contrast, mitotic cells displayed high Ca2+ concentrations on chromatins. Mg2+ showed similar dynamics during the cell cycle (Strick et al., 2001). The increase of Ca2+ and Mg2+ in the nucleus during the transition from interphase to metaphase chromosomes was thought to be causally linked to chromosome condensation. Coincidently, the physiological concentration of Mg2+ was shown to promote the self-assembly of similar DNA/chromatin in vitro (Inoue et al., 2007; Nishikawa and Ohyama, 2013). It is currently unclear about the source of cations that promote chromosome packaging, most likely from certain intracellular stores. In this line of thinking, it is tempting to speculate the possibility of the nuclear envelope as the cation store that regulates chromosome condensation (and decondensation) during mitosis. The nucleus envelope is connected with endoplasmic reticulum (ER), where a major intracellular Ca2+ store (Meldolesi and Pozzan, 1998), and starts to break down during the early phase of mitosis and is restored at the end of mitosis (Smoyer and Jaspersen, 2014). It is possible that the envelope breakdown causes Ca2+ release while restoration of the envelope causes the reuptake of Ca2+ and thus decrease Ca2+ in the nucleus.

The potential role of scaffold proteins in chromosome packaging during mitosis

While it is well established that in eukaryotic cells DNA is first packaged by wrapping on histone cores (Beshnova et al., 2014; Cherstvy and Teif, 2014; Kornberg, 1974), a role for scaffold proteins in the higher-order chromosomal packaging has been proposed (Laemmli, Cheng et al. 1977; Swedlow and Hirano 2003; Belmont 2006). Scaffold proteins such as condensins and topoisomerase II (TOPOII) display characteristic temporal expression during mitosis and are associated with mitotic chromosomes, especially on the axis. However, some studies have seriously challenged the view that scaffold proteins are the organizers of chromosomal packaging (Belmont, 2006). The model proposed here advocates a central role of DNA repeats in chromosome packaging during mitosis. I envision that scaffold proteins, specifically TOPO II and condensins, which appear to be recruited to chromosomes at a relatively late stage when the packaging is nearly complete (Kireeva et al., 2004), facilitate and stabilize RPs that are formed as a consequence of cation increase. I will describe the function of TOPOII and condensins in this process in a little more detail from this perspective. For RPs to proceed, topological tensions will be introduced in chromatins around RAs. TOPO II may function in chromatins surrounding RAs to remove the tensions and thus facilitate RPs. The requirement of TOPO II in mitotic chromosome condensation is probably transient; when RA formation is completed, so is the function of TOPO II. This may explain the temporal involvement of TOPO II in chromosomal condensation (Hirano and Mitchison, 1993; Maeshima and Laemmli, 2003) but not during maintenance when the chromosome condensation is completed (Hirano and Mitchison, 1993). When RPs (and thus RAs) are formed, condensins bind to the paired chromatins in RAs, which may have specific structural features that are required for condensins to load. The ring structure of condensins (Hirano, 2006) is ideal for bundling parallel chromatin fibers and thus stabilizing RPs. In this way, the loading of condensins onto mitotic chromosomes depends on RA formation. This view is consistent with the facts that condensins load onto chromosomes at a relatively late stage of condensation (Maeshima and Laemmli, 2003) and are required not for condensation but for maintaining the stability of mitotic chromosomes (Hudson et al., 2003). Depletion of condensins would increase the kinetics of RA disassociation, which may explain the delay of chromosome condensation observed after ScII/SMC2 knockout (Hudson et al., 2003). Coincidently, the idea that condensins localize to RAs and that TOPO II is found in the chromatins proximal to RAs is consistent with the alternated distribution of these proteins along the axis (Maeshima and Laemmli, 2003), which is probably a tandem array of RAs (Tang, 2011b). This also coincides with the observation that in chromosomes reconstituted in vitro, condensin but not TOPO II is enriched in chromatin crosslinking knots (König et al., 2007).

Condensins are able to introduce supercoiling in closed DNA circles (Kimura and Hirano, 1997; Kimura et al., 1999). Because of this activity, I propose that, in addition to stabilizing RAs, condensins may transform chromatin loops around RAs into supercoils. This postulated condensin-mediated supercoiling may provide an important mechanism to further condense chromatins. This type of packaging is expected to occur during the late stage of chromosome packaging during mitosis.

Implications of the model

The core idea of the proposed theory is that the cation-regulated sequential RPs program orderly chromatin folding during the packaging of chromosomes in mitosis and conversely that progressive cation decrease leads to orderly RP dissociation and mitotic chromosome decondensation. This packaging/unpackaging process during mitosis is not stochastic. Rather, it is largely, if not totally, guided by the coordinated action of DNA repeats. If this theoretical consideration is proven, it will provide a simple mechanism for reproducibly folding chromosomes during the cell cycle because of the expected precise folding that is mediated by RPs. In addition, the cation-dynamics-regulated RPs provide a straightforward means to couple the progression of the cell cycle to the sequential chromosome condensation and decondensation.

This model predicts that interfering with cation will affect chromosome packaging (e.g., artificially blocking the decrease of cations will block the transition of metaphase chromosomes to interphase chromosomes, whereas increasing cation in prophase will cause the formation of precocious metaphase chromosome). Changes in cation concentration are expected to affect the spatial organization of repetitive DNA in chromosomes. If possible, deleting massive repetitive elements will have an inhibitory effect on chromosome packaging during the cell cycle, and altering the distribution of repetitive DNA in the linear genome will also be expected to have a drastic effect on chromosome packaging.

This model makes a few specific predictions about the structural characteristics of eukaryotic chromosomes. (1) Structural reversibility. The cation-regulated RPs suggested here predict that the chromosome structure and morphology can be reversibly altered by changes in cation concentrations. Indeed, this has been demonstrated, both in vitro and in cultured cells (Cole 1967; Hudson et al., 2003; Marko 2008). (2) Condensation and decondensation during mitosis are progressive processes. Because RPs depend on the local concentration of the involved repeats, it follows that the region with a high density of homologous repeats will be packed early during chromosomal condensation but unpacked later during decondensation. This prediction is consistent with the behavior of tandem repeat regions (e.g., centromeres), which contain a high density of repeats and are condensed early but decondensed late during the cell cycle. (3) The symmetrical processes of chromosome condensation and decondensation. The chromosome packaging induced by cation increase from interphase to metaphase and the chromosome unpackaging induced by cation decrease from metaphase to interphase are symmetrical in terms of RA-governed chromosome organization (Fig. 1B).

Concluding remarks

Here, I propose that the progression of chromatin folding during the packaging of chromosomes in mitosis is a molecular process that is specified by the cation-regulated sequential formation of RPs. This RP-coordinated chromatin folding is coupled to the progression of the cell cycle via the dynamics of cation concentrations. In the scenario dictated by this model, one can envision the process of RP-directed precision in the folding of chromatin. From this perspective, the seemingly complicate packaging of mitotic chromosomes during mitosis is in fact surprisingly “simple”.

Previous investigation of cell-cycle-regulated chromosome packaging focused mainly on the morphological and structural description of chromosome dynamics. The mechanistic search has been largely concentrated on the involvement of specific proteins (e.g., histones and scaffolding proteins). Although packaging activity has been suggested for DNA elements called scaffold/matrix attachment regions (SARs/MARs), the function of these DNA elements is interpreted in the context of scaffolding proteins. The model presented here provides a novel conceptual framework to understand the molecular pathway of chromatin folding during mitosis. In this model, repetitive DNA elements (not proteins) are the central organizers of chromatin packaging during mitosis.

Prior studies have identified gene-specific functions of repetitive DNA. However, it is hard to generalize that this is the sole function of repetitive DNA, which occupies a large portion of the genomes of higher organisms. The model proposed here provides a generalizable concept to define the specific biological function of repetitive DNA in chromosomal packaging.

Acknowledgments

S.J.T. was supported by NIH grants (NS079166 and DA036165).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adolph KW, Cheng SM, Laemmli UK. Role of nonhistone proteins in metaphase chromosome structure. Cell. 1997;12:805–16. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(77)90279-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin GS, Brooks NJ, Robson RE, Wynveen A, Goldar A, Leikin S, Seddon JM, Kornyshev AA. DNA double helices recognize mutual sequence homology in a protein free environment. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2008;112:1060–4. doi: 10.1021/jp7112297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belmont AS. Mitotic chromosome structure and condensation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2006;18:632–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beshnova DA, Cherstvy AG, Vainshtein Y, Teif VB. Regulation of the nucleosome repeat length in vivo by the DNA sequence, protein concentrations and long-range interactions. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2014;10:e1003698. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bojanowski K, Ingber DE. Ionic control of chromosome architecture in living and permeabilized cells. Exp. Cell Res. 1998;244:286. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron IL, Smith NK, Pool TB. Element concentration changes in mitotically active and postmitotic enterocytes. An x-ray microanalysis study. J. Cell Biol. 1979;80:444–450. doi: 10.1083/jcb.80.2.444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherstvy AG, Kornyshev AA, Leikin S. Temperature-dependent DNA condensation triggered by rearrangement of adsorbed cations. J. Physical Chem. B. 2002;106:13362. [Google Scholar]

- Cherstvy AG, Teif VB. Structure-driven homology pairing of chromatin fibers: the role of electrostatics and protein-induced bridging. J. Biol. Physics. 2013;39:363–385. doi: 10.1007/s10867-012-9294-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherstvy AG, Teif VB. Electrostatic effect of H1-histone protein binding on nucleosome repeat length. Physical Biol. 2014;11:044001. doi: 10.1088/1478-3975/11/4/044001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole A. Chromosome structure. Theor. Biophys. 1967;1:305–375. [Google Scholar]

- Cournac A, Koszul R, Mozziconacci J. The 3D folding of metazoan genomes correlates with the association of similar repetitive elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:245–255. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cremer T, Cremer M. Chromosome territories. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2010;2:a003889. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danilowicz C, Lee CH, Kim K, Hatch K, Coljee VW, Kleckner N, Prentiss M. Single molecule detection of direct, homologous, DNA/DNA pairing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:19824–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911214106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Frutos M, Raspaud E, Leforestier A, Livolant F. Aggregation of nucleosomes by divalent cations. Biophysical J. 2001;81:1127. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75769-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehghani H, Dellaire G, Bazett-Jones DP. Organization of chromatin in the interphase mammalian cell. Micron. 2005;36:95. doi: 10.1016/j.micron.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano T. At the heart of the chromosome: SMC proteins in action. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;7:311. doi: 10.1038/nrm1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano T, Mitchison TJ. Topoisomerase II does not play a scaffolding role in the organization of mitotic chromosomes assembled in Xenopus egg extracts. J. Cell Biol. 1993;120:601–612. doi: 10.1083/jcb.120.3.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath P, Hörz W. The compaction of mouse heterochromatin as studied by nuclease digestion. FEBS Lett. 1981;134:25–8. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(81)80542-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson DF, Vagnarelli P, Gassmann R, Earnshaw WC. Condensin Is required for nonhistone protein assembly and structural integrity of vertebrate mitotic chromosomes. Dev. Cell. 2003;5:323. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00199-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue S, Sugiyama S, Travers AA, Ohyama T. Self-assembly of double-stranded DNA molecules at nanomolar concentrations. Biochem. 2007;46:164. doi: 10.1021/bi061539y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerzmanowski A, Staron K. Mg2+ as a trigger of condensation-decondensation transition during mitosis. J. Theor. Biol. 1980;82:41–46. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(80)90089-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall MD, Warley A, Morris IW. Differences inapparent elemtal composition of tissues and cells using a fully quantitative X-ray microanalysis system. J. Micros. 1985;138:35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Kimura K, Hirano T. ATP-dependent positive supercoiling of DNA by 13S condensin: a biochemical implication for chromosome condensation. Cell. 1997;90:625. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80524-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura K, Rybenkov VV, Crisona NJ, Hirano T, Cozzarelli NR. 13S condensin actively reconfigures DNA by introducing global positive writhe: implications for chromosome condensation. Cell. 1999;98:239. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81018-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kireeva N, Lakonishok M, Kireev I, Hirano T, Belmont AS. Visualization of early chromosome condensation: a hierarchical folding, axial glue model of chromosome structure. J. Cell Biol. 2004;166:775–785. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200406049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- König P, Braunfeld M, Sedat J, Agard D. The three-dimensional structure of in vitro reconstituted Xenopus laevis chromosomes by EM tomography. Chromosoma. 2007;116:349–72. doi: 10.1007/s00412-007-0101-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornberg RD. Chromatin structure: a repeating unit of histones and DNA. Science. 1974;184:868–871. doi: 10.1126/science.184.4139.868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loukin S, Kung C. Manganese effectively supports yeast cell-cycle progression in place of calcium. J. Cell Biol. 1995;131:1025–37. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.4.1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X, Klonoski JM, Resch MG, Hansen JC. In vitro chromotin self-association and its relevance to genome architecture. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2006b;84:411–417. doi: 10.1139/o06-068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeshima K, Laemmli UK. A two-step scaffolding model for mitotic chromosome assembly. Dev. Cell. 2003;4:467. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00092-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marko JF. Micromechanical studies of mitotic chromosomes. Chromosome Res. 2008;16:469–497. doi: 10.1007/s10577-008-1233-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meldolesi J, Pozzan T. The endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ store: a view from the lumen. Trends Biochem. Sciences. 1998;23:10. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01143-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishikawa J.-i., Ohyama T. Selective association between nucleosomes with identical DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:1544–1554. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulson JR, Laemmli UK. The structure of histone-depleted metaphase chromosomes. Cell. 1977;12:817–828. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(77)90280-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poirier MG, Marko JF. Mitotic chromosomes are chromatin networks without a mechanically contiguous protein scaffold. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:15393–15397. doi: 10.1073/pnas.232442599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raspaud E, Chaperon I, Leforestier A, Livolant F. Spermine-induced aggregation of DNA, nucleosome, and chromatin. Biophysical J. 1999;77:1547. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77002-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smoyer CJ, Jaspersen SL. Breaking down the wall: the nuclear envelope during mitosis. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2014;26:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strick R, Strissel PL, Gavrilov K, Levi-Setti R. Cation-chromatin binding as shown by ion microscopy is essential for the structural integrity of chromosomes. J. Cell Biol. 2001;155:899–910. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200105026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swedlow JR, Hirano T. The making of the mitotic chromosome: modern insights into classical questions. Mol. Cell. 2003;11:557–569. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00103-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang SJ. Chromatin organization by repetitive elements (CORE): a genomic principle for the higher-order structure of chromosomes. Genes. 2011a;2:502–515. doi: 10.3390/genes2030502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang S-J. A model of DNA repeat-assembled mitotic chromosomal skeleton. Genes. 2011b;2:661–670. doi: 10.3390/genes2040661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang S-J. A model of repetitive-DNA-organized chromatin network of interphase chromosomes. Genes. 2012;3:167–175. doi: 10.3390/genes3010167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teif VB, Bohinc K. Condensed DNA: condensing the concepts. Prog. Biophy. Mol. Biol. 2011;105:208. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wroblewski J, Roomans GM, Madsen K, Friberg U. X-ray microanalysis of cultured chondrocytes. Scan. Electron Microsc. 1983;2:777–784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang XY, Horz W. Analysis of highly purified satellite DNA containing chromatin from the mouse. Nucleic Acids Res. 1982;10:1481–1494. doi: 10.1093/nar/10.5.1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]