Abstract

Discrimination based on one’s racial or ethnic background is one of the oldest and most perverse practices in the United States. While much of this research has relied on self-reported racial categories, a growing body of research is attempting to measure race through socially-assigned race. Socially-assigned or ascribed race measures how individuals feel they are classified by other people. This paper draws on the socially assigned race literature and explores the impact of socially assigned race on experiences with discrimination using a 2011 nationally representative sample of Latina/os (n=1,200). While much of the current research on Latina/os has been focused on the aggregation across national origin group members, this paper marks a deviation by using socially-assigned race and national origin to understand how being ascribed as Mexican is associated with experiences of discrimination. We find evidence that being ascribed as Mexican increases the likelihood of experiencing discrimination relative to being ascribed as White or Latina/o. Furthermore, we find that being miss-classified as Mexican (ascribed as Mexican, but not of Mexican origin) is associated with a higher likelihood of experiencing discrimination compared to being ascribed as white, ascribed as Latina/o, and correctly ascribed as Mexican. We provide evidence that socially assigned race is a valuable complement to self-identified race/ethnicity for scholars interested in assessing the impact of race/ethnicity on a wide range of outcomes.

Keywords: Race, Ethnicity, Discrimination, Socially assigned Race, Ascribed Race, Racial Misclassification

Introduction/Overview

Racial, ethnic, gender, and sexual orientation1 based discrimination is one of the central experiences that continue to plague the United States. Research literature has consistently documented the differences in outcomes due to discrimination for such populations (Anderson 2013; Reskin 2012). As a result of discrimination, several populations have experienced social inequalities, which have impacted their livelihood and overall well-being (Branscombe, Schmitt, and Harvey 1999; Harrell 2000; Leonardelli and Tormala 2003). While scholars in the social sciences have developed a sustained interest in exploring how discrimination influences the lives of communities of color (Keith and Herring, 1991;Jud and Walker 1997; Williams 1999; Williams et al. 2003 ; Reskin 2012), our examination seeks to delve “deeper” into the dynamics of discrimination within the pan-ethnic Latina/o community by assessing how discrimination varies based on how Latinos are viewed by others.

Extant research has identified strong relationships between racial discrimination and many outcome domains. Such outcomes include group identity (Clark and Clark, 1949; Banfield and Dovidio 2013; Branscombe, et al. 2012; Sellers et al. 2006), political behaviors (Schildkraut 2005), mental and physical health (Brodish et al. 2011; Stuber et al. 2003; Williams, Neighbors, and Jackson 2003), and generational health (Goosby and Heidbrink 2013; Nicklett, 2011). Social scientists have also discovered correlating relationships between discrimination and other domains such as home ownership and housing conditions (Painter, Gabriel, and Myers 2001; Turner et al. 2002; Williams et al. 2005), harsher criminal penalties (Steffensmeier, Ulmer, and Kramer 1998), negative labor market outcomes (Bertrand and Mullainathan 2004), and segmented consumer markets (Harris, Henderson, and Williams 2005).

Although this research area is extensive and has increased our understanding of the role, impact, and disparity that discrimination plays in the lives of many people of color in the U. S., our additional examination can contribute to distinctions for the bases of discriminatory behaviors and “targeted” groups. Our analysis intends to shed light on discrimination and race/ethnicity measurement in three specific areas within this larger literature: 1) identification of contributors of discrimination with the relatively lesser studied Latina/o population, 2) the role of socially ascribed race (how others view you in society) on discrimination, and 3) unpacking of the pan-ethnic classification of Latina/os by exploring national origin variations in discrimination (i.e. the Mexican origin population) relative to being misclassified as Mexican when you are from a different national origin group. The results of this analysis will advance our collective knowledge of the central concept of discrimination by providing some perspective on how being viewed as Mexican by others drives discrimination experiences within the largest minority population in the United States.

Discrimination and the Latina/o Population

Discrimination can be defined as the unequal treatment of an individual based on specific and unique characteristics. According to the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), these characteristics can include a person’s age, disability status, national origin, race/color, religion, or sexual orientation (U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, 2009). Race is defined as a group of people identified as distinct from other groups because of physical or genetic traits shared by the group. Ethnicity is defined as the state of belonging to a social group that has a common national or cultural tradition. Most directly tied to our analysis, discrimination based on one’s race/ethnicity has become one of the most debatable and stimulating social issues in the U.S. and most studied among social scientists. However, a vast majority of this work focuses on the African American population (Aguirre and Turner 2004; Chae, et, al. 2010; Chae, et. al. 2011; Chae, et. al. 2012; Dotterer, McHale, and Crouter 2009; Odom and Vernon-Feagans 2010; Roberts et al. 2008; Seaton, Yip, and Sellers 2009; Sellers et al. 2003; Smalls et. al. 2007).

Given our review of the literature, a large share of the research has focused on discrimination relative to African Americans and less work has focused on Latina/os. While, there has been some important work focused on the discrimination experiences of other groups, including Latina/os (Darity, Dietrich, and Hamilton, 2005; Chou, Asnaani, and Hofmann 2012; Lorenzo-Blanco et al. 2013; Ornelas and Hong 2012; Trevino and Ernst 2012; Molina and Simon, 2013), we know far less about the implications of discrimination within the pan-ethnic Latina/o population.

While limited, there is literature that suggests Latina/os experience discrimination to a similar degree as other racial or ethnic groups (Gee et al. 2006; LaVeist, Rolley, and Diala, 2003; Stuber et al. 2003), with many Latina/os reporting discriminatory experiences similar to those of African-Americans (Golash-Boza and Darity 2008). Furthermore, as documented in the existing research, historically Latina/os have faced and continue to face substantial discrimination in their workplace, neighborhoods, and in the public education system (Lopez, Morin, and Taylor 2010; Pew Research Center 2007). Recent work situated in South Florida, for example, links discrimination and mental health among Latina/o youth, suggesting a significant link between depression and Latina/os with darker skin when compared to Latina/os of a lighter skin complexion (Burgos and Rivera, 2009). Our growing, but still limited knowledge of how discrimination manifests itself among Latina/os is important due to the increased presence of the Latina/o population in the U.S., its socio-political make-up and noteworthy diversity within the pan-ethnic Latina/o population. Greater knowledge and understanding can highlight the ways in which discrimination impacts lives in this community.

Although it may appear as though the daily experiences of Latina/os mirror that of African-Americans within the context of racial/ethnic discrimination, there are some important differences between these two large racial/ethnic groups. These differences have implications for the nature and extent to which discrimination can impact the life chances of Latina/os, as well as how researchers approach their analyses of discrimination on this population. For example, Latina/os who have immigrated to the United States relatively recently may face discrimination due to their immigration and legal status (Finch, Kolody, and Vega 2000; Rumbaut 1994). Similarly, language has been a source of discrimination experiences among Latina/os (Pew Research Center, 2007; Haubert Weil 2009; Kossoudji 1988). These factors suggest that research focused on discrimination aimed at Latina/os will need to be sensitive to some of these nuances specific to the population that may predict discrimination experiences. Our analysis includes measures for these factors.

Although there are some factors that may affect discrimination experiences specific to the pan-ethnic Latina/o population, there are others that they share with African Americans. For example, skin color may be a factor that influences discrimination experiences for Latina/os similar to research findings for African Americans. Throughout U.S. history, racial and ethnic discrimination has been a major dilemma (Myrdal 1944), with individuals with darker skin complexion experiencing the greatest disadvantage (DuBois 1899; Knapp, Keil, et al. 1995; Hunter 2002; Rondilla, Spickard, and Spickard 2007; Stevenson 1996; Goldsmith et al. 2006; Hamilton, Goldsmith, and Darity 2009). There has been work that has examined phenotypic discrimination among Latina/os in the United States based on the 1990 Latino National Political Survey, finding that Mexicans and Cubans with darker skin complexion experience high levels of discrimination in the labor market, which affected their occupational chances (Murguia and Telles 1996; Espino and Franz 2002). We therefore include a measure of skin color in our models.

Socially Assigned Race, Stereotypes, and Discrimination of Mexican Origin

While once widely debated, most scholars now agree that the notion of race is a socio-political construct. As a result, race should not be interpreted as being scientific or anthropological in nature due to the lack of a biological etiology (Vargas et al. 2015). Within the framework of race being socially constructed, social science research has provided two general approaches to measure race; self-identification and social-assignment or ascribed race. Much of the research interested in exploring disparities across racial/ethnic groups has typically relied on asking respondents to self-identify their race/ethnicity in surveys (Lewis 2003; Saperstein 2006; Roth 2010; Stepanikova 2010; Campbell and Troyer 2011; Cheng and Powell 2011; Veenstra 2011; Saperstein 2012; Song and Aspinall 2012; N. Vargas 2014). While this approach has proven its value over time, some contend that people make a determination about an individual’s race before asking them how they self-identify (Saperstein 2006; Roth 2010; Stepanikova 2010; Cheng and Powell 2011; Veenstra 2011; Song and Aspinall 2012; N. Vargas 2015; Vargas et al. 2015; Garcia et al. 2015; Irizarry 2015).

The notion that others may define your race regardless of your own identity is known as “socially assigned race” or “ascribed race” has proven to be a very important measure in predicting the level of discrimination an individual will encounter as well their health outcomes. For example, Jones et al. (2008) demonstrated that if respondents self-identified as Hispanic, Native American, or mixed-race, but were socially assigned as White, they were more likely to report very good and excellent health compared to respondents who self-identified as the same race, but who were ascribed as non-White (i.e. White advantage) (Jones et al. 2008). Corroborating the Jones et al. (2008) findings, MacIntosh et al. (2013) recently demonstrated that respondents who self-identified as racial/ethnic minorities, but who are ascribed as white are more likely to receive preventive vaccinations and less likely to report healthcare discrimination, compared to respondents ascribed as non-White (MacIntosh et al. 2013).

In another work which examines racial self-identification and perception by others, Saperstein and Penner (2010) investigated this relationship within the criminal justice system. From this study, authors found that racial self-identification was strongly linked to one’s likelihood of being incarcerated and that the general population in America links “blackness” to negative traits and criminal status (Saperstein and Penner 2010). More specifically, those respondents who have been incarcerated were more likely to identify and be seen as black; and more likely not identify or is perceived as white. This pattern among incarcerated respondents held up regardless how they had been perceived and identified themselves previously (in this longitudinal study). This literature suggests that being defined as white by others may have positive outcomes, and certain experiences or statuses (i.e. incarceration, welfare recipients, etc.) can create have the effect of a negotiation process in which individuals are negotiated with everyday interactions. Finally, their research introduces the fluidity of racial identification over time and an individual’s circumstances.

We then hypothesize that Latina/o respondents who are viewed by others as being white are less likely to report experiences with discrimination than those who are ascribed as Mexican or Latina/o. We do discuss later the stigmatization and the negative images that are associated with being Latina/o and/or Mexican. We are also interested in potential negative consequences associated with racial or ethnic misclassification2. In work that examines racial misclassification, Campbell and Troyer (2011) find that misclassified American Indians have higher rates of psychological distress (Campbell and Troyer 2011). Similarly, in what scholars have labeled the “whitening of Latina/os,” recent work by Vargas (2014) has shown that respondents who report higher socioeconomic status and lighter skin are more likely to be viewed as white compared to respondents who have lower socioeconomic status and darker skin (Vargas 2014).

Our analysis intends to advance our understanding of the bounds of racial misclassification by exploring the further specification of national origin group members under the Latina/o pan-ethnic umbrella. In this case, what are the consequences associated with being misidentified or classified as Mexican, as opposed to being white or Latina/o? Does being viewed by others as Mexican for non-Mexican origin respondents yield higher rates of discrimination than being viewed as white, Latina/o, or being correctly classified as Mexican (ascribed as Mexican and of Mexican origin)? This research addresses how pan-ethnic aggregation and national origin may mask important variations that are traditionally treated as noise (modeled in the error term) in quantitative analysis. Taking into account the heterogeneity and diversity of the Latina/o population in the U.S., this study analyzes the impact of being ascribed as Mexican on experiences with discrimination.

Latina/o sub-groups tend to reside in different areas of the United States, can have different cultural practices/norms, have different immigration experiences, and have different levels of social economic status. However, it is unlikely that members of the general population make these important distinctions when interacting with Latina/os in the United States. We approach this analysis from the standpoint that the size of the Mexican origin population in the U.S., historical perceptions, and current political context surrounding immigration policy can lead to greater discrimination for Latina/os who are viewed Mexican.

The Mexican Origin Experience in the U.S

Mexican Americans are the largest Latina/o sub-group, making up over 65 percent of the total Latina/o population. While historically situated in the Southwest, migration streams have spread the Mexican origin population to the southern and northeastern parts of the U.S; while expanding their presence in the Mid- and Southwest. Latina/os have been the largest “contributor” to this country’s population’s growth rates with the Mexican origin population representing a substantial portion of that population’s growth. Concomitantly, the size and fast growth of the Latina/o population has been associated with a sense of fear toward this group by non-Hispanics (as affecting the racial/ethnic makeup of the nation, creating cultural and value differences, preponderance of Spanish language use, etc.) Individuals being identified Latina/os, or more specifically, as Mexican origin, may be more likely to experience discriminatory behavior. The added case of mistaken identity (i.e. perceived as Mexican when that it is not the person’s national origin) can compound discrimination experiences. We will briefly outline the historical context of discrimination directed toward Mexicans in the United States, and the current climate surrounding common perceptions of Mexicans as primarily immigrant’s, especially undocumented ones.

As the largest segment of Latina/os, the Mexican origin community has been long standing in the United States. Mexican presence in the current U.S. preceded the expansion of U.S. into the now American southwest (Gutierrez 1983). The aftermath of the Mexican–American War resulted in the acquisition of the northwest territory of Mexico and placed residing Mexicans under U.S. governance. Historically, those of Mexican origin have been stereotyped as lazy, dumb, morally deficient, and violent (Aguirre 1972). The field of Mexican-American history has documented the pattern of discriminatory practices and negative stereotypes (Foley 1997; Ngai 2004; Vasquez 2010) in a variety of settings and locations.

In addition to individuals’ discriminatory behaviors, there have been institutional practices that have treated those of Mexican origin differentially. In 1930, the U.S. Bureau of the Census added the category of “Mexican” as part of the range of racial categories (Gross 2003; Rodriquez 2000). At that time in history, it was perceived that all Mexican laborers were of mixed race. Due to this instance, census enumerators were instructed to recognize individuals as Mexicans, if they had been born in Mexico, had parents born in Mexico, or who could not be classified as being White, Negro, Indian, Chinese, or Japanese (Ortiz and Telles 2012). This practice occurred during the 1930 Census and the separate racial category of Mexican was removed in subsequent censuses.

In addition, Mexican American children were part of a segregated school system in the Southwest (San Miguel 1987), with separate schools and the rationale was language and “negative cultural values and traditions (San Miguel, 1987). In the late 1960’s and in the early 1970’s, attempts to integrate the desegregated school systems in the Southwest, designated Mexican Americans as white so as to integrate segregated African American schools with segregated Mexican schools. Several court cases in Denver, Corpus Christi, and Houston sought to have Mexican Americans as an identifiable ethnic minority group for the purpose of school desegregation. In these jurisdictions, the courts recognized Mexican Americans as a distinct minority group for the purpose of school assignments (Foley 1995; Menchaca 1995). Mexicans also experienced segregated public facilities, lynching, and other discriminatory practices (Barrera 1979; Almaguer 1994) as well as a limited opportunity structure in employment, education, and health care access and treatment. Thus our focus upon those of Mexican origin as having significance as “objects” of discriminatory treatment has a strong basis for paring out from the Latina/o pan-ethic grouping.

Two studies have examined how the perceived statuses of Mexican origin respondents affect how others see them racially/ethnically. In Buriel and Vasquez (1982), Mexican American and Anglo adolescents were asked to assign characteristics (positive and negative) about Mexican origin people. Consistently, Anglo adolescents had more negative ratings; while Mexican American adolescents were positive about their own group. They did find some negative shifts among second and third generation Mexican Americans. Their concluding comments suggested greater exposure to American culture and norms contributes to prevailing negative stereotypes in American society. Finally, Ortiz and Telles (2012; 2008) examined the racial treatment of Mexican Americans who acknowledge their history of racialization (Barrera 1979; Vasquez 2010). In this research, ascribed race or perceptions about being Mexican corresponded with experiences with discrimination. Key dimensions of skin tone (Gomez 2000), educational attainment, dense social networks with other Mexicans, and interaction with Anglos contributed to greater incidence of discrimination. Mexican Americans with higher educational attainment have more contact with Anglos experiencing a greater prevalence of negative Mexican origin stereotyping. The incidences of discrimination occur more frequently in the workplace, in school settings, and with the police. Our brief coverage of the relation between being of Mexican origin and stereotypes and discrimination (Andrade, 1982), ties to our current research effort to examine the ascribed “category” of Mexican origin in addition to being identify as the Latina/o and white racial categories. Differentiation within national origin groups is an important area that has been relatively under-researched.

The legacy of discrimination directed toward the Mexican-origin population in the U. S. has been reinforced by the current anti-immigrant socio-political context. Analysis of public opinion data suggests that the U.S. population’s views toward immigration policy have become more conservative over time (Espenshade and Calhoun 1993; Espenshade and Hempstead 1996; Harwood 1986), driven largely by a rise in undocumented immigration (Cornelius 1982; Passel 1986). Furthermore, research has also shown that the general American population has associated the surge in undocumented immigrants with increased levels of crime (Cornelius 1982) and an overall eradication of American political values (Day 1990; Huntington 2004; Schlesinger 1998).

Our theory, that being defined as Mexican leads to greater discrimination, is driven not only by a rise in conservatism, but also by an association made by the mass public regarding negative views about immigration and the Mexican population. Using surveys from 2007–2008, Pérez (2010) finds that negative attitudes towards Latina/o immigrants are associated with restrictive policy preferences towards both legal and undocumented immigrants. Using a survey experiment conducted in 2010, Hartman, Newman, and Bell (2014) found that racial antipathy towards Hispanics plays a role in anti-immigrant sentiment and in support for anti-immigrant policies. Furthermore, they find support for the idea that anti-immigrant sentiment and anti-immigrant policy preferences act in part as “coded” expressions of anti-Hispanic prejudice. While this work does not make explicit that negative attitudes are Mexican specific, given the disproportionately high rate of migration from Mexico; it is very likely that Americans attitudes are directed specifically at who they believe to be Mexican.

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) reports over 4.6 million removals between 1997–20131 over twice the total number of all deportations before this period (Golash-Boza and Hondagneu-Sotelo 2013). Directly tied to our theory, DHS reports that in 2013 over 240,000 Mexicans were removed. That was over five times the number of removals from the next highest country of Guatemala at 47,000. Immigration policy scholars have also found that Mexicans are the primary target of border enforcement efforts. For example, Lopez et al. (2011) find that 73% of removals are Mexicans, although undocumented immigrants from Mexico represent only 58% of undocumented immigrants present in the U.S. For these reasons, we anticipate that non-Mexicans who are socially ascribed as being of Mexican origin will report higher levels of discrimination than other Latina/os in our sample, while controlling for the lived experiences of Latina/os (language, skin color, nativity, national origin, social economic status, and gender).

Methods

Data Collection

For our analysis, we took advantage of a 2011 Latino Decisions/ImpreMedia survey that was designed in collaboration with the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Center for Health Policy at the University of New Mexico. Latino Decisions conducted the field work for the survey and worked in conjunction with the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Center for Health Policy (University of New Mexico) to design a survey instrument focusing on health and Latina/os. The sample and design allowed us not only to test the relationship between socially assigned race and experiences with discrimination but also allowed us to explore the heterogeneous nature of the Latina/o experience. This is an ideal dataset for our research question, as we have built in indicators of how Latina/os believe they are classified in the United States as well as questions regarding national origin, nativity, acculturation, and citizenship. Taken together, this is the only nationally representative dataset of Latina/os that measures socially assigned race, features a discrimination variable, and contains key indicators used when studying Latina/os.

A total of 1,200 Latina/os were interviewed over the phone through two samples: 600 Latina/o registered voters and 600 non-registered Latina/os. The non-voter sample was added for the purpose of ensuring that our ability to explore the relationship between multiple measures of race and health related outcomes included non-citizens, who are obviously not included in registered voter samples. Given this design, half of the registered voting sample was foreign born, among the non-registered sample, 63 percent of this sample was foreign born.

All phone calls were administered by Pacific Market Research in Renton, Washington. The survey has an overall margin of error of +/− 4 percent, with an AAPOR response rate of 29 percent. Latino Decisions selected the 21 states with the highest number of Latina/o registered voters, states that collectively account for over 95 percent of the Latina/o electorate. Although this sample was designed to capture a large margin of Latina/o voters, these states also comprise 91 percent of the overall Latina/o adult population. The voter sample was drawn from registered voters by using the official statewide databases of registered voters, maintained by elections officials in each of the 21 states. A separate list of Hispanic households was used to identify respondents for the non-voter sample, which was designed to be proportionate to the overall population in those states. Probability sampling methods were employed in both samples based on the respective lists used to identify the universe of potential participants. Respondents were interviewed by telephone, and they could choose to be interviewed in either English or Spanish. A mix of cell phone only and landline households were included in the sample, and both samples are weighted to match the 2010 Current Population Survey universe estimate of Latina/os and Latina/o voters respectively for these 21 states with respect to age, place of birth, gender, and state. The survey was approximately 22 minutes long and was fielded from September 27, 2011 to October 9, 2011.

Measures

The primary outcome variable of interest is experience with discrimination using a single survey question: “Have you personally experienced discrimination, or been treated unfairly because of your race or ethnicity?” The response categories for this measure are 0= No and 1= Yes. This measure is specific to racial/ethnic discrimination, making it ideal for our analysis, and has been utilized in numerous studies (Harris et al. 2013; Hossain and Susan 2010; Ro and Choi 2009; Gee et al. 2008; Gee et al. 2006). To provide context on this outcome, a 2007 study by the Pew Hispanic Center shows that among Latina/o adults, 31 percent responded that they or a family member has experienced discrimination in 2002, 38 percent responded they experienced discrimination in 2006, and 41 percent responded they or a family member has experienced discrimination in 2007 (Pew Hispanic Center, 2007).

Our main explanatory variables are four mutually-exclusive categories that are created using ascribed race and national origin survey questions. Our specific question on ascribed race was: “ How do other people usually classify you in the United States? Would you say you are primarily viewed by others as…? Please Select One” The response categories for this variable are Hispanic/Latina/o, Black/African American, White, American Indian/Native American, Mexican, and Some Other Group. The categories of Black/African American, American Indiana/Native American, and Some Other Group are dropped due to small sample sizes (n=118). The three socially assigned race categories are White, Latina/o, and Mexican totaling 1,082 respondents. We also make use of a national origin question to create our match and mismatch categories among ascribed as Mexican respondents. The specific survey question was: “[Hispanics/Latinos] have their roots in many different countries in Latin America. To what country do you or your family trace your ancestry? [OPEN-ENDED WITH LIST OF ALL COUNTRIES].” Two categories make use of the national origin question: Latina/os who are ascribed as Mexican but are not of Mexican origin and Latina/os who are ascribed as Mexican and who are of Mexican origin. The distribution on the national origin indicator shows that Mexican origin Latina/os make up the majority of respondents representing 52.75 percent of the sample, followed by Puerto Ricans (8.58 percent), Spanish (6.08 percent), Cubans (4.67 percent), Columbians (2.75 percent), Salvadorians (2.33 percent), Dominican Republicans (2.25 percent) and Guatemalans (2 percent).

Finally, we control for a handful of measures that have been found to be correlated with discrimination in previous research. Among the demographic variables, we include: standard measures of income, educational attainment, age, and gender. To assess income we have included several dummy variables representing different income categories: $40,000–$60,000; $60,000–$80,000; and >$80,000, with less than $40,000 serving as the reference category. We also include a variable of “unknown” income in the model which includes respondents who did not report their income as a means of saving cases. Finally, we control for cultural factors including nativity, language of survey, and self-reported skin color on a five point scale ((Very Light -17.22 percent, Light -25.57 percent, Medium -47.36 percent, Dark -6.50 percent, Very Dark -3.34 percent). Summary statistics for all variables used in this analysis are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary Statistics (n=985) using a 2011 Latino Decisions/ImpreMedia Survey.

| Variables | Mean | Standard Deviation | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discrimination | 0.345 | 0 | 1 | |

| Ascribed as White | 0.117 | 0 | 1 | |

| Ascribed as Latina/o | 0.494 | 0 | 1 | |

| Ascribed as Mexican | 0.389 | 0 | 1 | |

| Mismatch-Mex | 0.062 | 0 | 1 | |

| Match-Mex | 0.327 | 0 | 1 | |

| Age | 51.623 | 17.182 | 18 | 98 |

| Education1 | 3.471 | 1.547 | 1 | 6 |

| Female | 0.586 | 0 | 1 | |

| Spanish Language2 | 0.503 | 0 | 1 | |

| U.S. Born3 | 0.431 | 0 | 1 | |

| Skin Color4 | 2.53 | 0.962 | 1 | 5 |

| Income Missing | 0.191 | 0 | 1 | |

| Less $40K | 0.485 | 0 | 1 | |

| $40-$60K | 0.130 | 0 | 1 | |

| $60-$80K | 0.073 | 0 | 1 | |

| $80 Plus | 0.122 | 0 | 1 |

Education (1=Grade 1–8, 2=Some HS, 3=HS, 4=Some College, 5=College Grad, 6=Post-Grad)

Interview was conducted in Spanish.

Nativity (0=Foreign Born, 1=U.S.-Born)

Skin Color (1=Very Light, 2=Light, 3=Medium, 4=Dark, 5=Very Dark)

Statistical Analysis

Our analytical approach is intended to determine the relationship between socially assigned race and experiences with discrimination within a nationally representative sample of Latina/o adults. Our primary focus is to determine the effect of being socially assigned Mexican on reported discrimination compared to being socially assigned as Latina/o or white. We then focus on further decomposing the ascribed as Mexican category to explore differences in the probability of experiencing discrimination for respondents who ascribe Mexican, but who are not of Mexican origin (being misclassified as Mexican) compared to respondents who ascribed as Mexican and who are of Mexican origin, as well as respondents who are ascribed as white or Latina/o. We will then conduct logistic regression to examine the differences across socially assigned racial categories on the probability of experiencing discrimination.

Results

We begin with a discussion of the distributions from our sample (which are provided in tables 1 and 2). Regarding our socially assigned categories (Table 1) a large segment of our sample indicated that they are socially ascribed as Latina/o or Hispanic (49.35 percent). About 11.74 percent of our sample indicated that they are ascribed as White, and 38.72 percent are ascribed as Mexican. Among the ascribed as Mexican category (421 respondents), 32.72 percent of the respondents are not of Mexican origin (variable name: Mismatch-Mex) compared to 6.19 percent of respondents who are of Mexican origin (variable name: Match-Mex), which are shown in the bottom half of table 1. A crosstab of our main dependent variable shows that 34.5 percent of our sample has experienced discrimination. The mean age in our sample is 52, and the majority of our sample has at least a high school education. Moreover, at least half of our sample completed the survey in Spanish, and just under half of the sample indicated that they are of Mexican ancestry (43 percent), both consistent with national data on Latina/os from the U.S. Census, except for Mexican ancestry as about 64 percent of the Latina/o population is of Mexican ancestry. In regards to citizenship and nativity, just under half of our full sample is U.S. born, with a large majority reporting U.S. citizenship. In sum, our sample is representative of U.S. Latina/os, as the U.S. Census estimates that about 63 percent of Latina/os over the age 25 have a high school education, and about 74 percent of Latina/os over five years of age speak Spanish at home.

Table 1.

Crosstab of Ascribed Race and Mis-Match Categories using a 2011 Latino Decisions/ImpreMedia Survey.

| Variables | Variable Name | Ascribed Race Survey Response | Country of Origin Survey Response | Number of Observations | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original | Ascribed as White | White | 127 | 11.74 | |

| Ascribed as Latina/o | Latina/o | 534 | 49.35 | ||

| Ascribed as Mexican | Mexican | 421 | 38.91 | ||

| Creation of Mismatch Categories | |||||

| Mismatch1 | Mismatch-Mex | Mexican | Other Than Mexico | 67 | 32.72 |

| Match-Mex | Mexican | Mexico | 354 | 6.19 | |

Mis-Match Categories (separating ascribed as Mexican respondents (n=421) by country of origin.

Our logistic regression models 1–4 decompose the ascribed as Mexican category to explore differences in the probability of experiencing discrimination for respondents who are viewed by others as being Mexican, but who are not actually of Mexican origin (reference category) compared to respondents who are accurately ascribed as Mexican origin, as well as respondents ascribed as white or Latina/o. We estimate models 1–4, iteratively to first understand differences in discrimination controlling for age, education, gender, and language of interview (model 1). We then estimate this model and include nativity (model 2), income (model 3), and skin color (model 4) to isolate the effects of nativity, income, and skin color on experiences with discrimination.3

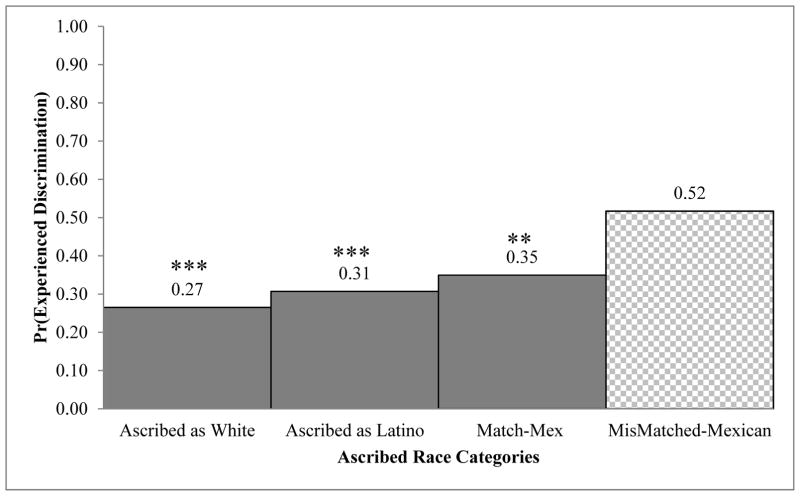

As shown in models 1–4, we can conclude that respondents who are mistakenly ascribed as being of Mexican-origin compared to white or Latina/o, or who are accurately ascribed as being Mexican experience higher levels of discrimination. In fact, among respondents who are ascribed as being white the odds of experiencing discrimination are 67 percent lower (p<0.001) than respondents who are misclassified as Mexican, holding all else constant. Respondents who are ascribed as being Latina/o or Hispanic have odds of reporting discrimination 59 percent (p<0.001) lower than respondents who are misclassified as being Mexican, holding all else constant. Finally, respondents who are of Mexican origin and accurately classified as being Mexican the odds of experiencing discrimination decrease by 51 percent (p<0.05) compared to non-Mexican origin Latina/os who are misclassified as Mexican, holding all else constant.

To help visualize these relationships we computed the predicated probabilities of experiencing discrimination for each of the ascribed race categories of theoretical interest, holding all else constant. These relationships are shown in figure 1, and we find that respondents who are socially assigned as white, report the lowest probability of experiencing discrimination (27 percent), followed by being ascribed as Latino (31 percent). Moreover, we find that respondents who are correctly classified as Mexican are 35 percent likely to experience discrimination. Lastly, respondents who are misclassified as being Mexican when they are from another national origin group are most likely to experience discrimination (52 percent). This confirms that Latinos who are viewed as Mexican by others face greater discrimination in US society than Latinos viewed as white. This figure provides strong visual support for our primary theory that Latina/os who are misclassified as Mexican have a greater likelihood of experiencing discrimination, even after accounting for the internal variation among the Latina/o population and other potential sources of discrimination in our models.

Figure 1.

Adjusted Predicted Probabilities of Logistic Coefficients for Regression of Socially Assigned Race on Experienced Discrimination using a 2011 Latino Decisions/ImpreMedia Survey (n=959).

Note. Controlling for age, gender, education, income, nativity, language of interview, and skin color (all of which were set to their mean or mode values).

*P < 0.1, **P < 0.05, ***P < 0.01 for the differences between MisMatched Mexican (ascribed as Mexican but not of Mexican origin) versus Match Mex (Ascribed as Mexican and of Mexican origin), ascribed as Latino, and Ascribed as white.

In addition to our measures of socially assigned race, among the control variables, only education and nativity (being U.S. born) proved to be significant. In line with the extant literature on the relationship between education and discrimination, education is positively correlated with experiencing discrimination among Latina/os. We also find that being born in the U.S. also increases your likelihood of experiencing discrimination, which has shown to be the case in studies focused on immigrants. We do not find evidence that age, income, gender, or skin color is a matter on experiencing discrimination among our sample. Finally, language of interview is not an important factor in experienced discrimination. The lack of a significant relationship between skin color and discrimination is somewhat surprising given the strong correlation identified in the literature. However, these studies have not accounted for this more recently developed concept of ascribed race.

Conclusions and Discussion

The focus of the current work was to take an in-depth look at the effects of socially assigned race on discrimination among the Latina/o population in the United States, with a particular focus on the relationship between being accurately classified and misclassified as being Mexican and discrimination. Our analysis finds that being ascribed as Mexican, compared to being ascribed as white or Latina/o, increases your likelihood of experiencing discrimination among Latinos in the United States. Moreover, once we decompose the ascribed as Mexican category, we find that non-Mexican origin Latina/os who are misclassified as being Mexican report the highest levels of discrimination, even after taking into consideration age, education, income, nativity, language, gender, and skin color, all key components of the Latina/o experience.

These findings are important, as they highlight differentiating discriminatory effects on Latina/o sub-groups that would be hidden or overlooked if aggregated across Latina/o subgroups. These findings suggest that being socially assigned as Mexican carries with it a heavy burden and speaks to the systematic racialization that exists for Latina/os, particularly for Mexicans. Findings from this research highlight the racialization and the historical legacy of discrimination among Mexican origin populations. Research on Mexican Americans has provided evidence of the racialization of this group, both historically and in contemporary life in the U.S. (Almaguer 1994; Barrera 1979; Foley 1997; Gomez 2007; Massey 2009; Vasquez 2010). An extended pattern of labor migrants has placed many Mexican Americans at the lower end of the economic hierarchy and their historic placement near the bottom of the racial hierarchy (Montejano 1987). This was preceded by the conquest of the original Mexican inhabitants in American Southwest which fostered notions about a distinct racial category of “Mexican” in the prevalent public sphere. Mexican origin persons encounter significant racial barriers, which have resulted in limited opportunities for them. Ortiz and Telles (2012) have demonstrated that Mexican Americans lag educationally and economically even after several generations in the U. S., as a result of this treatment. They have been thus limited to mostly working class jobs and from successfully integrating into middle class society.

While Latinos of Mexican-origin are more likely to report discrimination than Latinos from other backgrounds, interestingly, we find discrimination experiences are even more likely for Latinos who are mistaken for being Mexican. We believe that this may be driven by not only the racialization of the Mexican population in the United States, but also the variation in discrimination experiences among Mexican Americans. The inter-relationship between a historical legacy of discrimination among third-generation Mexican Americans who are middle-class and structurally integrated into U.S. occupations, institutions, and mainstream culture is the focus of research by Vasquez (2010). She describes these Mexican Americans as living at an identity and cultural “crossroads”, with respondents who are either part European-descent or have lighter skin and hair colors have “flexible ethnicity,” that enable them to traverse multiple racial terrains with some dexterity (Anzaldúa 1987). This could lead many Mexican Americans to report lower levels of discrimination than non-Mexicans who are ascribed as Mexican, particularly when we control for skin color.

Our research findings reconfirm the importance of examining national origin groups within the pan-ethnic groupings to examine differential effects and/or compounded consequences of being Latina/o and Mexican origin. However, we find that personal identification choices can hit a wall of racialization, as well; whereas “Mexican ethnicity is in large part determined by things much greater than our personal volition” (Macias 2006: xiii). This highlights the importance of thinking beyond self-identification for measurement of race, ethnicity, and in this case, national origin. Our measurement approach of utilizing not only an ascribed identity, but to combine that with the more traditional self-identification measure has led to what we believe is an important suggestion for the measurement of important concepts central to scholars interested in race and ethnicity. Particularly in today’s socio-demographic climate where immigration attitudes appear to be influencing relationships across racial groups, assessing how being mistaken for a negatively viewed group impacts outcomes such as discrimination is both timely and important. These results hold even after controlling for regional variation, emphasizing the need to replicate our measurement approach in future work.

Our findings also highlight interesting patterns for the relationship between education and experiences with discrimination in that higher educated Latina/os are more likely to report experiences with discrimination. One plausible explanation for this relationship is that with greater levels of education, Latina/os are put into positions that require more contact with more non-Latina/os co-workers/neighbors (Ortiz and Telles 2012). This increased contact could then lead to an increased chance of experiencing discrimination. For example, research has shown that higher income and older African Americans are more likely to experience discrimination than their less educated and lower income counterparts (Halanych et al. 2011). In line with the extant literature on the relationship between education and discrimination, education is positively correlated with experiencing discrimination among Latina/os (Berkel et al. 2010; Ortiz and Telles 2012; Pere , Fortuna, and Alegría 2008). We also find that nativity (being U.S. born) proved to be positively associated with experiencing discrimination, which has shown to be the case in studies focused on immigrants (Córdova Jr. and Cervantes 2010; Finch, Kolofy, and Vega 2000; Pere , Fortuna, Alegría 2008; Perez, Sribney, and Rodríguez 2009).

While we believe this study has important implications for social scientists, we acknowledge that there are a number of unsettled issues with our analysis due to the limitations inherent to the research design. Most prominently, scholars in the future should consider how the race of the discrimination agent may influence the impact of discrimination on Latina/os well-being. The Latino National Survey (2006) reveals that while the majority of respondents who reported experiences with discrimination indicated that they had been discriminated against by a white individual in their last discrimination experience (64.7%), another 12.6% reported being discriminated by another Latina/o, 8.3% by an African American, 3.4% by an Asian American. We encourage survey researchers to develop an instrument that provides the power to conduct this analysis, as it may be possible that the experience of being discriminated by someone from your own ethnic group could have a pronounced impact on the well-being of individuals. Furthermore, it would be very interesting to see if the findings from this study travel to other populations who have been socially assigned with negative stereotypes. For example, does being ascribed as someone of middle-eastern descent, or as an African American lead to similar experiences of discrimination among other racial or ethnic communities? These are questions we hope to see other researches take on replicating our measurement approach with data tailored to these purposes.

As the U.S. continues to be more racially and ethnically diverse, understanding how the lives of individuals in society vary by race and ethnicity becomes more critical, particularly for pan-ethnic groups (Asian, Native Americans, and Latina/os). This comes at a time when the U.S. Census Bureau is developing numerous experiments on how to eliminate missing data among Latina/o respondents when asked the question regarding self-reported race. Our paper advocates for approaching the task of measuring race and ethnicity from the standpoint of ascribed race, in addition to traditional measures of self-reported race. This requires moving beyond single measures of race and/or ethnicity which are usually constructed through self-identification. We believe that the approach we take in this analysis can be applied with other outcomes in mind. It is likely that if being mistakenly classified as Mexican leads to higher rates of discrimination, this could also lead to negative health outcomes such as depression, decreased wages, and potentially a greater sense of commonality with other Latina/os. We encourage scholars to continue the advancement of our measures of race and ethnicity in an effort to better reflect the lived experience of these communities with our measurement approaches. We also encourage scholars to include other Latin American national origin response categories within the ascribed race question a task that has not been examined at this time to test for response bias.

Table 3.

Logistic Coefficients for Regression of Socially Assigned Race on Experienced Discrimination using a 2011 Latino Decisions/ImpreMedia Survey.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||

| VARIABLES | B | Odds Ratio | β | Odds Ratio | β | Odds Ratio | β | Odds Ratio |

| Reference: Mismatch-Mex (respondents who are ascribed as Mexican but not of Mexican origin) | ||||||||

| Ascribed as White | −1.197*** (0.353) | 0.302*** | −1.207*** (0.354) | 0.299*** | −1.191*** (0.356) | 0.304*** | −1.109*** (0.359) | 0.330*** |

| Ascribed as Latina/o | −0.930*** (0.293) | 0.394*** | −0.888*** (0.294) | 0.411*** | −0.845*** (0.295) | 0.429*** | −0.901*** (0.297) | 0.406*** |

| Match-Mex | −0.703** (0.298) | 0.495** | −0.690** (0.299) | 0.501** | −0.669** (0.300) | 0.512** | −0.704** (0.303) | 0.495** |

|

| ||||||||

| Age | 0.002 (0.004) | 1.002 | 0.002 (0.004) | 1.002 | 0.002 (0.004) | 1.002 | 0.002 (0.004) | 1.002 |

| Education1 | 0.132** (0.052) | 1.141** | 0.132** (0.052) | 1.141** | 0.122** (0.055) | 1.130** | 0.110 (0.056) | 1.116 |

| Female | 0.020 (0.137) | 1.020 | 0.014 (0.137) | 1.014 | 0.000 (0.141) | 1.000 | −0.012 (0.143) | 0.988 |

| Spanish Interview2 | −0.170 (0.152) | 0.844 | 0.056 (0.191) | 1.058 | 0.084 (0.194) | 1.088 | 0.147 (0.198) | 1.159 |

| U.S. Born3 | 0.355** (0.181) | 1.426** | 0.376** (0.183) | 1.457** | 0.366** (0.187) | 1.441** | ||

| Income Missing4 | 0.026 (0.209) | 1.026 | −0.074 (0.217) | 0.928 | ||||

| Inc. $40k-60K | 0.144 (0.209) | 1.155 | 0.146 (0.210) | 1.158 | ||||

| Inc. $60–80 | −0.404 (0.285) | 0.668 | −0.334 (0.287) | 0.716 | ||||

| Inc. $80 Plus | 0.243 (0.221) | 1.276 | 0.275 (0.223) | 1.316 | ||||

| Skin Color5 | 0.099 (0.077) | 1.104 | ||||||

| Adjusted R-Square | 0.0179 | 0.0209 | 0.0249 | 0.0247 | ||||

| Observations | 985 | 985 | 985 | 959 | ||||

Notes:

p<0.01,

p<0.05,

β is a logit coefficient, standard error in parenthesis

Education (1=Grade 1–8, 2=Some HS, 3=HS, 4=Some College, 5=College Grad, 6=Post-Grad)

Interview was conducted in Spanish.

Nativity (0=Foreign Born, 1=U.S.-Born)

Reference Category: Income Less than $40,000

Skin Color (1=Very Light, 2=Light, 3=Medium, 4=Dark, 5=Very Dark)

Footnotes

For this research, we focused our attention on discrimination specifically on Hispanic/Latina/os living in the U.S.

By mis-classification, we are noting situations in which an individual self-identifies with a particular racial/ethnic group and the ascribed racial/ethnic identification is of a different racial/ethnic group.

Prior to decomposing the ascribed as Mexican category by national origin to create our misclassification measure, we ran a logistic model on experiences with discrimination prior to the misclassification analysis that controls for age, education, gender, income, and language of interview. Here we find that being socially assigned as Mexican compared to being socially assigned as white or Hispanic/Latina/o increases the probability of reporting discrimination. In fact, Latina/os who are ascribed as being Mexican the odds of experiencing discrimination increase by 41.3 percent (p<0.05) compared to Latina/os who are ascribed as white, holding all else constant. Latina/o respondents who are ascribed as being Mexican the odds of experiencing discrimination increase by 26.2 percent (p<0.05) compared to Latina/os who are ascribed as Latina/o/Hispanic, holding all else constant.

The authors’ calculations using Homeland Security data – 2010 Yearbook of Immigration Statistics for FY 1997-FY 2010, and annual HSD announcements of year-end removal statistics for FY 2011- FY 2013. http://www.dhs.gov/immigration-statistics

Contributor Information

Edward D. Vargas, Center for Women’s Health and Health Disparities Research, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Nadia C. Winston, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Center for Health Policy at Meharry Medical College

John A. Garcia, Emeritus Professor at both the (ICPSR-Institute for Social Research-ISR (the University of Michigan), and School of Government and Public Policy (University of Arizona)

Gabriel R. Sanchez, Department of Political Science and RWJF Center for Health Policy, University of New Mexico

References

- 1.Aguirre Lydia R. In: La Causa Chicano: The Movement for Justice. Mangold Margaret., editor. New York: Family Service Association of America; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aguirre Adalberto, Turner Jonathan H. American Ethnicity: The Dynamics and Consequences of Discrimination. University of Michigan: McGraw-Hill; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Almaguer Tomas. Racial Fault Lines: The Historical Origins of White Supremacy in California. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson Kathryn F. Diagnosing Discrimination: Stress from Perceived Racism and the Mental and Physical Health Effects. Sociological Inquiry. 2013;83(1):55–81. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andrade Sally. Social Science Stereotypes of the Mexican American Woman. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1982;4(2):223–244. doi: 10.1177/07399863820042006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anzaldúa Gloria. Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. San Francisco, CA: Spinsters/Aunt Lute; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Araujo Beverly Y, Borrell Luisa N. Understanding the link between discrimination, mental health outcomes, and life chances among Latinos. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2006;29(2):245–266. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Banfield Jillian C, Dovidio John F. Whites’ perceptions of discrimination against Blacks: The influence of common identity. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2013;49(5):833–841. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barrera Mario. Race and Class in the Southwest: A Theory of Racial Inequality. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berkel Cady, Knight George P, Zeiders Katharine H, Tein Jenn-Yun, Roosa Mark W, Gonzales Nancy A, Saenz Delia. Discrimination and Adjustment for Mexican American Adolescents: A Prospective Examination of the Benefits of Culturally Related Values. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2010;20(4):893–915. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00668.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bertrand Marianne, Mullainathan Sendhil. Are Emily and Greg more employable than Lakisha and Jamal? A field experiment on labor market discrimination. American Economic Review. 2004;94(1):991–1013. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Branscombe Nyla R, Schmitt Michael T, Harvey Richard D. Perceiving Pervasive Discrimination among African Americans: Implications for Group Identification and Well-Being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;77(1):135–149. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brodish Amanda B, Cogburn Courtney D, Fuller-Rowell Thomas E, Peck Stephen, Malanchuk Oksana, Eccles Jacquelynne S. Perceived Racial Discrimination as a Predictor of Health Behaviors: the Moderating Role of Gender. Race and Social Problems. 2011;3(3):160–169. doi: 10.1007/s12552-011-9050-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burgos Giovani, Rivera Fernando. The (In)Significance of Race and Discrimination among Latino Youth: The Case of Depressive Symptoms. Sociological Focus. 2009;42(2):152–171. doi: 10.1080/00380237.2009.10571348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buriel Ray, Vasquez Richard. Stereotypes of Mexican Descent Persons: Attitudes of Three Generations of Mexican Americans and Anglo Americans. Journal of Cross Cultural Psychology. 1982;13(1):59–70. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Campbell Mary E, Troyer Lisa. Further Data on Misclassification: A Reply to Cheng and Powell. American Sociological Review. 2011;76(2):356–364. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chae David H, Nuru-Jeter Amani, Adler Nancy E. Implicit Racial Bias as a Moderator of the Association Between Racial Discrimination and Hypertension: A Study of Midlife African American Men. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2012;74:961–964. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3182733665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chae David H, Lincoln Karen H, Jackson James S. Discrimination, Attribution, and Racial Group Identification: Implications for Psychological Distress Among Black Americans in the National Survey of American Life (2001–2003) American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2011;81:498–506. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2011.01122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chae David H, Krieger N, Bennett GG, Lindsey JC, Barbeau EM. Implication of discrimination based on sexuality, gender, and race for psychological distress among working class sexual minorities: The United for Health Study, 2003–2004. International Journal of Health Services. 2010;40(4):589–608. doi: 10.2190/HS.40.4.b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheng Simon, Powell Brian. Misclassification by Whom? A Comment on Campbell and Troyer. American Sociological Review. 2011;76(2):347–355. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chou Tina, Asanani Anu, Hofmann Stefan G. Perception of Racial Discrimination and Psychopathology Across Three U.S. Ethnic Minority Groups. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2012;18(1):74–81. doi: 10.1037/a0025432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clark Kenneth B, Clark Mamie K. The Development of Consciousness of Self and the Emergence of Racial Identification in Negro Preschool Children. Journal of Social Psychology. 1939;10(4):591–599. [Google Scholar]

- 23.David Córdova, Jr, Cervantes Richard C. Intergroup and Within-Group Perceived Discrimination among U.S.-Born and Foreign-Born Latino Youth. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2010;32(2):259–274. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cornelius Wayne A. Interviewing Undocumented Immigrants: Methodological Reflections Based on Fieldwork in Mexico and the U.S. International Migration Review. 1982;16(2):378–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crook Errol D, Bryan Norman B, Hanks Roma, Slagle Michelle L, Morris Christopher G, Ross Mary C, Torres Herica M, Clay Williams R, Voelkel Christina, Walker Sheree, Arrieta Martha I. A Review of Interventions to Reduce Health Disparities Cardiovascular Disease in African-Americans. Ethinicity & Disease. 2009;19(2):204–208. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Day Christine L. What Older Americans Think: Interest Groups and Aging Policy. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Darity William, Jr, Dietrich Jason, Hamilton Darrick. Bleach in the Rainbow: Latin Ethnicity and Preference for Whiteness. Transforming Anthropology. 2005;13(2):103–10. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dotterer Aryn M, McHale Susan M, Crouter Ann C. The Development and Correlates of Academic Interests from Childhood through Adolescence. Journal of Education Psychology. 2009;101(2):509–519. doi: 10.1037/a0013987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Du Bois William EB. The Philadelphia Negro: A Social Study. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania; 1899. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Espenshade Thomas J, Hempstead Katherine. Contemporary American Attitudes Toward U.S. Immigration. International Migration Review. 1996;30(2):535–570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Espenshade Thomas J, Calhoun Charles A. An Analysis of Public Opinion toward Undocumented Immigration. Population Research and Policy Review. 1993;12(2):189–224. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Espino Rodolfo, Franz Michael M. Latino Phenotypic Discrimination Revisited: The Impact of Skin Color on Occupational Status. Social Science Quarterly. 2002;83:612–623. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Finch Brian K, Kolody Bohdan, Vega William A. Perceived Discrimination and Depression among Mexican-Origin Adults. California. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2000;41(3):295–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Flores Glenn. Racial and ethnic disparities in the health and health care of children. American Academy of Pediatrics. 2010;132(1):e281. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Foley Neil. The White Scourge: Mexicans, Blacks and Poor Whites in Texas Cotton Culture. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garcia John, Sanchez Gabriel R, Vargas Edward D, Ybarra Vicky, Sanchez-Youngman Shannon. Race as Lived Experience: The Impact of Multi-Dimensional Measures of Race on Self-Defined Health Status of Latinos. 2015 doi: 10.1017/S1742058X15000120. In Press, Du Bois Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gee Gilbert C, Ryan Andrew, Laflamme David J, Holt Jeanie. Self-Reported Discrimination and Mental Health Status among African Descendants, Mexican Americans, and Other Latinos in the New Hampshire REACH 2010 Initiative: The Added Dimension of Immigration. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(10):1821–1828. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.080085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Golash-Boza Tanya, Hondagneu-Sotelo Pierrette. Latino immigrant men and the deportation crisis: A gendered racial removal program. Latino Studies. 2013;11(3):271–292. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Golash-Boza Tanya, Darity William., Jr Latino racial choices: the effects of skin colour and discrimination on Latinos’ and Latina’ racial self-identifications. Ethnic and Racial Studies. 2008;31(5):899–934. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goldsmith Arthur, Hamilton Darrick, Darity William., Jr "Shades of Discrimination: Skin Tone and Wages". American Economic Review. 2006;96(2):242–245. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goosby Bridget J, Heidbrink Chelsea. Transgenerational consequences of racial discrimination for African-American Health. Social Compass. 2013;7(8):630–643. doi: 10.1111/soc4.12054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gomez Christina. The Continual Significance of Skin Color: An Exploratory Study of Latinos in the Northeast. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2000;22(1):94. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gomez Laura E. Manifest Destinies: The Making of the Mexican American Race. NY: New York University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gross Ariela J. Texas Mexicans and the Politics of Whiteness. Law and History Review. 2003;21(1):195–205. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gutierrez David. Significant to Whom? Mexican Americans and the History of the American West. Western Historical Quarterly. 1983;24(4):519–539. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Halnych Jewell H, Safford Monika M, Shikany James M, Cuffee Yendelela, Person Sharina D, Scarinici Isabel C, Kiefe Catarina I, Allison Jeroan J. The Association between Income, Education and Experiences of Discrimination in Older African American and European American Patients. Ethnicity & Disease. 2011;21(2):223–229. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hamilton Darrick, Goldsmith Arthur, Darity William., Jr "Shedding 'Light' on Marriage: The Influence of Skin Shade on Marriage for Black Females.". Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization. 2009;72(1):30–50. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Harrell Shelly P. A Multidimensional Conceptualization of Racism-Related Stress: Implications for the Well-Being of People of Color. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2000;70(1):42–57. doi: 10.1037/h0087722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Harris Anne-Marie G, Henderson Geraldine R, Williams Jerome D. Courting Customers: Assessing Consumer Racial Profiling and Other Marketplace Discrimination. Journal of Public Policy. 2005;24(1):163–171. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hartman Todd K, Newman Benjamin J, Scott Bell C. Decoding Prejudice Toward Hispanics: Group Cues and Public Reactions to Threatening Immigrant Behavior. Political Behavior. 2014;36:143–163. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Harwood Edwin. American Public Opinion and U.S. Immigration Policy. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Immigration and American Public Policy. 1986;487:201–212. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Haubert Weil Jeannie. Finding Housing: Discrimination and Exploitation of Latinos in the Post-Katrina Rental Market. Organization & Environment. 2009;22(4):491–502. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hu-Dehart Evelyn, Garcia Matthew, Coll Cynthia Garcia, Itzigsohn Jose, Orr Marion, Affigne Tony, Elorza Jorge. Latino National Survey (LNS)--New England, 2006. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research; 2006. ICPSR24502-v1. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hunter Margaret L. If you’re light you’re alright”: Light skin color as social capital for women of color. Gender and Society. 2002;16(2):175–193. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huntington Samuel P. Who are we? America’s great debate. United Kingdom: Free Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jones Camara P, Truman Benedict I, Elam-Evans Laurie D, Jones Camille A, Jones Clara Y, Jiles Ruth, Rumisha Susan F, Perry Geraldine S. Using Socially Assigned Race to Probe White Advantage in Health Status. Ethnicity & Disease. 2008;18(4):496–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jud Donald G, Walker James L. Discrimination by Race and Class and the Impact of School Quality. Social Science Quarterly. 1997;57(4):731–749. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Keith Verna M, Herring Cedric. Skin Tone and Stratification in the Black Community. The American Journal of Sociology. 1991;97(3):760–778. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Knapp Rebecca G, Keil Julian E, Sutherland Susan E, Rust Phillip F, Hames Curtis, Tyroler Herman A. Skin Color and Cancer Mortality among Black Men in the Charleston Heart Study. Clinical Genetics. 1995;47(4):200–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1995.tb03959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kossoudji Sherrie A. English Language Ability and the Labor Market Opportunities of Hispanic and East Asian Immigrant Men. Journal of Labor Economics. 1988;6(2):205–228. [Google Scholar]

- 61.LaVeist Thomas A, Rolley Nicole C, Diala Chamberlain. Prevalence and Patterns of Discrimination among U.S. Health Care Consumers. International Journal of Health Services. 2003;33(2):331–344. doi: 10.2190/TCAC-P90F-ATM5-B5U0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Leonardelli Geoffrey J, Tormala Zakary L. The Negative Impact of Perceiving Discrimination on Collective Well-Being: The Mediating Role of Perceived In-Group Status. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2003;33(4):507–514. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lewis Amanda E. Race in the School Yard: Negotiating the Color Line in Classrooms and Communities. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lorenzo-Blanco Elma I, Unger Jennifer B, Ritt-Olsen Anamara, Soto Daniel, Baezconde-Garbanti Lourdes. A Longitudinal Analysis of Hispanic Youth Acculturation and Cigarette Smoking: The Roles of Gender, Culture, Family, and Discrimination. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2013;15(5):957–968. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lopez Mark H, Gonzalez-Barrera Ana, Motel Seth. As Deportations Rise to Record Levels, Most Latinos Oppose Obama’s Policy. Washington, D.C: Pew Hispanic Center; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lopez Mark H, Morin Rich, Taylor Paul. Illegal Immigration Backlash Worries, Divides Latinos. Washington, D.C: Pew Hispanic Center; [Google Scholar]

- 67.Macias Thomas. Mestizo in America: Generations of Mexican Ethnicity in the Suburban Southwest. Tucson: University of Arizona Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 68.MacIntosh Tracy, Desai Mayur M, Lewis Tene T, Jones Beth A, Nunez-Smith Marcella. Socially-Assigned Race, Healthcare Discrimination and Preventative Healthcare Services. PLOS One. 2013;8(5):1–7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Massey Douglas S. Racial Formation in Theory and Practice: The Case of Mexicans in the United States. Race and Social Problems. 2009;1(1):12–26. doi: 10.1007/s12552-009-9005-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Menchaca Martha. The Mexican Outsiders: A Community History of Marginalization and Discrimination in California. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Molina Kristine, Simon Y. Everyday discrimination and chronic health conditions among Latinos: The moderating role of socioeconomic position. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2013;37(5):868–880. doi: 10.1007/s10865-013-9547-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Montejano David. Anglos and Mexicans in the Making of Texas: 1836–1986. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Murguia Edward, Telles Edward E. Phenotype and Schooling among Mexican Americans. Sociology of Education. 1996;69(4):276–289. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Myrdal Gunnar. An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy. New York: Harper Brothers Publishers; 1944. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ngai Mai. Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nicklett Emily J. Socioeconomic status and race/ethnicity independently predict health decline among older diabetics. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:684. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Odom Erica C, Vernon-Feagans Lynne. Buffers of Racial Discrimination: Links with Depression Among Rural African-American Mothers. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72(2):346–359. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00704.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ornelas India J, Hong Seunghye. Gender Differences in the Relationship between Discrimination and Substance Use Disorder among Latinos. Substance Use and Misuse. 2012;47(12):1349–1358. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2012.716482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ortiz Vilma, Telles Edward. Racial Identification and Racial Treatment of Mexican Americans. Race and Social Problems. 2012;4(4):41–56. doi: 10.1007/s12552-012-9064-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Painter Gary, Gabriel Stuart, Myers Dowell. Race, Immigrant Status, and Housing Tenure. Journal of Urban Economics. 2001;49(1):150–167. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pérez Debra J, Fortuna Lisa, Alegría Margarita. Prevalence and Correlates of Everyday Discrimination among U.S. Latinos. Journal of Community Psychology. 2008;36:421–433. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Perez Debra, Sribney William M, Rodríguez Michael A. Perceived Discrimination and Self-Reported Quality of Care Among Latinos in the United States. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2009;24(3):548–554. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1097-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pérez Efrén O. Explicit Evidence on the Import of Implicit Attitudes: The IAT and Immigration Policy Judgments. Political Behavior. 2010;32(4):517–545. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pew Research Center. Perceptions of Discrimination. Washington, D.C: 2007. [accessed August 12, 2014]. http://www.pewhispanic.org/2007/12/13/iv-perceptions-of-discrimination/ [Google Scholar]

- 85.Quinn Sandra C, Kumar Supriya, Freimuth Vicki S, Musa Donald, Casteneda-Angarita Nestor, Ridwell Kelley. Racial Disparities in Exposure, Susceptibility, and Access to Health Care in the US H1N1 Influenza Pandemic. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101(2):285–293. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.188029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Reskin Barbara F. The Race Discrimination System. Annual Review of Sociology. 2012;38(1):17–35. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Roberts Calpurnyia B, Vines Anissa I, Kaufman Jay S, James Sherman A. Cross-Sectional Association between Perceived Discrimination and Hypertension in African-American Men and Women: The Pitt County Study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2008;167(5):624–632. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rodriguez Clara E. Changing Race: Latinos, The Census, and The History of Ethnicity in the United States. NY: New York University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rondilla Joanne, Spickard Paul. Is Lighter Better? Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Rosenbloom Susan R, Way Niobe. Experiences of Discrimination among African–American, Asian–American, and Latino Adolescents in an Urban High School. Youth & Society. 2004;35(4):420–451. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Roth Wendy D. Racial Mismatch: The Divergence between form and Function in Data for Monitoring Racial Discrimination of Hispanics. Social Science Quarterly. 2010;91(5):1288–1311. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Rumbaut Rubén G. The Crucible Within: Ethnic Identity, Self-Esteem, and Segmented Assimilation Among Children of Immigrants. International Migration Review. 1994;28(4):748–794. [Google Scholar]

- 93.San Miguel Guadalupe., Jr . Let All of Them Take Heed: Mexican Americans and the Campaign for Educational Equality in Texas 1910–1981. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Saperstein Aliya. Double-checking the Race Box: Examining Inconsistency between Survey Measures of Observed and Self-reported Race. Social Forces. 2006;85(1):57–74. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Saperstein Aliya. Capturing Complexity in the United States: Which Aspects of Race Matter and When? Ethnic and Racial Studies. 2012;35(8):1484–1502. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Saperstein Aliya, Penner Andrew M. The Race of a Criminal Record: How Incarceration Colors Racial Perceptions. Social Problems. 2010;57(1):92–113. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Seaton Eleanor K, Yip Tiffany, Sellers Robert M. A Longitudinal Examination of Racial Identity and Racial Discrimination Among African American Adolescents. Child Development. 2009;80(2):406–417. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01268.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sellers Robert M, Copeland-Linder Nikeea, Martin Pamela P, L’Heureux Lewis R. Racial Identity Matter: The Relationship between Racial Discrimination and Psychological Functioning in African-American Adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2006;16(2):197–216. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sellers Robert M, Caldwell Cleopatra H, Schmeelk-Cone Karen H, Zimmerman Marc A. Racial Identity, Racial Discrimination, Perceived Stress, and Psychological Distress among African American Young Adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2003;44(3):302–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Schildkraut Deborah J. The Rise and Fall of Political Engagement among Latinos: The Role of Identity and Perceptions of Discrimination. Political Behavior. 2005;27(3):285–312. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Schlesinger Arthur M., Jr . The disuniting of America: Reflections on a multicultural society. New York. WW: Norton; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Song Miri, Aspinall Peter. Is Racial Mismatch a Problem for Young ‘Mixed Race’ People in Britain? The Findings of Qualitative Research. Ethnicities. 2012;12(6):730–753. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Smalls Ciara, White Rhonda, Chavous Tabbye, Sellers Robert M. Racial Ideological Beliefs and Racial Discrimination Experiences as Predictors of Academic Engagement Among African American Adolescents. Journal of Black Psychology. 2007;33(3):299–330. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Steffensmeier Darrell, Ulmer Jeffery, Kramer John. The Interaction of Race, Gender, and Age in Criminal Sentencing: The Punishment Cost of Being Young, Black, and Male. Criminology. 1998;36(4):763–798. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Stepanikova Irena. Applying a Status Perspective to Racial/Ethnic Misclassification: Implications for Health. Advances in Group Processes. 2010;27:159–183. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Stevenson Brenda. Life in Black and White: Family and Community in the Slave South. New York: Oxford University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Stuber Jennifer, Galea Sandra, Ahern Jennifer, Blaney Shannon, Fuller Crystal. The Association between Multiple Domains of Discrimination and Self-assessed Health: A Multilevel Analysis of Latinos and Blacks in Four Low-Income New York City Neighborhoods. Health Services Research. 2003;38(6 Pt 2):1735–1760. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2003.00200.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Telles Edward E, Ortiz Vilma. Generations of Exclusion: Mexican Americans, Assimilation, and Race. New York: Russel Sage Foundation; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Trevino Brandy, Ernst Frederick A. Skin Tone, Racism, Locus of Control, Hostility, and Blood Pressure in Hispanic College Students. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2012;34(2):340–348. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Turner Margery A, Ross Stephen L, Gaister George C, Yinger John. Discrimination in Metropolitan Housing Markets: National Results from Phase 1 HDS 2000. Washington, DC: Urban Inst., Dep. Housing and Urban Development; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Vargas Edward D, Sanchez Gabriel, Kinlock Ballington. The Enhanced Self-Reported Health Outcome Observed in Hispanics/Latinos who are Socially-Assigned as White is Dependent on Nativity. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2015 Dec;17(6):1803–10. doi: 10.1007/s10903-014-0134-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Vargas Nicholas. Off White: Colour-Blind Ideology at the Margins of Whiteness. Ethnic and Racial Studies. 2014;37(13):2281–2302. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Vargas Nicholas. Latina/o Whitening: Which Latinas/os Self-Classify as White and Report Being Perceived as White by Other Americans? Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race. 2015;12(1):119–136. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Vasquez Jessica M. Blurred Borders for Some but not “Others”: Racialization, ‘Flexible Ethnicity’, Gender, and Third-Generation Mexican American Identity. Sociological Perspectives. 2010;53(1):45–72. [Google Scholar]