Abstract

Prostate cancer (PC) is a biologically heterogeneous disease with variable molecular alterations underlying cancer initiation and progression. Despite recent advances in understanding PC heterogeneity, better methods for classification of PC are still needed to improve prognostic accuracy and therapeutic outcomes. In this study we computationally assembled a large virtual cohort (n=1,321) of human PC transcriptome profiles from 38 distinct cohorts and, using pathway activation signatures of known relevance to PC, developed a novel classification system consisting of 3 distinct subtypes (named PCS1 to 3). We validated this subtyping scheme in 10 independent patient cohorts and 19 laboratory models of PC, including cell lines and genetically engineered mouse models. Analysis of subtype-specific gene expression patterns in independent datasets derived from luminal and basal cell models provides evidence that PCS1 and PCS2 tumors reflect luminal subtypes, while PCS3 represents a basal subtype. We show that PCS1 tumors progress more rapidly to metastatic disease in comparison to PCS2 or PCS3, including PSC1 tumors of low Gleason grade. To apply this finding clinically, we developed a 37-gene panel that accurately assigns individual tumors to one of the 3 PCS subtypes. This panel was also applied to circulating tumor cells (CTCs) and provided evidence that PCS1 CTCs may reflect enzalutamide resistance. In summary, PCS subtyping may improve accuracy in predicting the likelihood of clinical progression and permit treatment stratification at early and late disease stages.

Keywords: prostate cancer, data integration, classification, pathway, prognosis

INTRODUCTION

Prostate cancer (PC) is a heterogeneous disease. Currently defined molecular subtypes are based on gene translocations (1,2), gene expression (3,4), mutations (5–8), and oncogenic signatures (9,10). In other cancer types, such as breast cancer, molecular classifications predict survival and are routinely used to guide treatment decisions (11,12). However, the heterogeneous nature of PC, and the relative paucity of redundant genomic alterations that drive progression, or that can be used to assess likely response to therapy, have hindered attempts to develop a classification system with clinical relevance (13).

Recently, molecular lesions in aggressive PC have been identified. For example, overexpression of the androgen receptor (AR) due to gene amplification has been observed in castration resistant PC (CRPC) (14). Presence of AR variants (AR-Vs) that do not require ligand for activation have been reported in a large percentage of CRPCs and have been correlated with resistance to AR targeted therapy (15). The oncogenic function of enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) was found in cells of CRPC, and recurrent mutations in the speckle-type POZ protein (SPOP) gene occur in ~15% of PC (16,17). Expression signatures related to these molecular lesions have also been developed to predict patient outcomes. While, in principle, signature-based approaches could be used independently in small cohorts (4,10), there is a potential for an increase in diagnostic or prognostic accuracy if signatures reflecting gene expression perturbations relevant to PC could be applied to large cohorts containing thousands of clinical specimens.

Here we present the results of an integrated analysis of an unprecedentedly large set of transcriptome data, including from over 4,600 clinical PC specimens. This study revealed that RNA expression data can be used to categorize PC tumors into 3 distinct subtypes, based on molecular pathway representation encompassing molecular lesions and cellular features related to PC biology. Application of this subtyping scheme to 10 independent cohorts and a wide range of preclinical PC models strongly suggests that the subtypes we define originate from inherent differences in PC origins and/or biological features. We provide evidence that this novel PC classification scheme can be useful for detection of aggressive tumors using tissue as well as blood from patients with progressing disease. It also provides a starting point for development of subtype-specific treatment strategies and companion diagnostics.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Merging transcriptome datasets and quality control

To assemble a merged dataset from diverse microarray and high throughput sequencing platforms, we applied a median-centering method followed by quantile scaling (MCQ) (18). Briefly, each dataset was normalized using the quantile method (19). Probes or transcripts were assigned to unique genes by mapping NCBI entrez gene IDs. Redundant replications for each probe and transcript were removed by selecting the one with the highest mean expression. Log2 intensities for each gene were centered by the median of all samples in the dataset. Each of the matrices was then transformed into a single vector. The vectors for the matrices were scaled by the quantile method to avoid a bias toward certain datasets or batches with large variations from the median values. These scaled vectors were transformed back into the matrices. Finally, the matrices were combined by matching the gene IDs in the individual matrices, resulting in a merged dataset of 2,115 samples by 18,390 human genes. To evaluate the MCQ-based normalization strategy, we applied the XPN (cross platform normalization) (20) method to the same datasets and compared it to the merged data from MCQ. Multi-dimensional scaling (MDS) between samples was performed to assess batch effects. The same MCQ approach with the quantile method, or the Single Channel Array Normalization (SCAN) method (21), was also applied for normalization and batch correction of data from the independent cohorts.

Computing pathway activation score

We used the Z-score method to quantify pathway activation (22). Briefly, the Z-score was defined by the difference between the error-weighted mean of the expression values of the genes in a gene signature and the error-weighted mean of all genes in a sample after normalization. Z-scores were computed using each signature in the signature collection for each of the samples, resulting in a matrix of pathway activation scores.

Determination of the optimal number of clusters

Non-negative matrix factorization (NMF) clustering with a consensus approach is useful to elucidate biologically meaningful classes (23). Thus, we applied the consensus NMF clustering method (24) to identify the optimal number of clusters. NMF was computed 100 times for each rank k from 2 to 6, where k was a presumed number of subtypes in the dataset. For each k, 100 matrix factorizations were used to classify each sample 100 times. The consensus matrix with samples was used to assess how consistently sample-pairs cluster together. We then computed the cophenetic coefficients and silhouette scores for each k, to quantitatively assess global clustering robustness across the consensus matrix. The maximum peak of the cophenetic coefficient and silhouette score plots determined the optimal number of clusters.

Classification using a 14-pathway classifier

We constructed a classifier, where a set of predictors consists of 14 pathways, using a naïve Bayes machine learning algorithm. For training the classifier, we used the pathway activation scores and subtype labels of the result of the NMF clustering process. We then computed the misclassification rate using stratified 10-fold cross validation. To assess performance, we adopted a 3-class classification as a 2-class classification (e.g., PCS1 versus others) and computed the average area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves from all 3 of 2-class classifications. Finally, we applied the 14-pathway classifier to assign subtypes to the specimens.

Identifying subtype enriched genes (SEGs)

Wilcoxon rank-sum test and subsequent false discovery rate (FDR) correction with Storey’s method (25) were employed to identify differentially expressed genes between the subtypes. Genes were selected with FDR<0.001 and fold change ≥1.5, resulting in 428 SEGs.

Development of a 37-gene diagnostic panel

A random forest machine learning algorithm was employed to develop a diagnostic gene panel. For parameter estimation and training the model, we used the merged dataset. Initially, the model comprised of the 428 SEGs as a set of predictors and subtype label of the merged dataset was used as a response variable for model training. To verify the optimal leaf size, we compared the mean squared errors (MSE) obtained by classification of leaf sizes of 1 to 50 with 100 trees, resulting in an optimal leaf size of 1 for model training. We then permuted the values for each gene across every sample and measured how much worse MSE became after the permutation. Imposing a cutoff of importance score at 0.5, we selected the 37 genes for subtyping. From the computation of MSE growing 100 trees on 37 genes and on the 428 SEGs, the 37 genes we chose gave the same MSE as the full set of 428 genes. ROC curve analyses and 10-fold cross-validation were also conducted to assess the performance of a classification ensemble.

Statistical analysis

We performed principal component analysis (PCA) and MDS for visualizing the samples to assess their distribution using pathway activation profiles. Wilcoxon rank-sum statistics were used to test for significant differences in pathway activation scores between the subtypes. Kaplan-Meier analysis, Cox proportional hazard regression, and the Chi-square test were performed to examine the relationship(s) between clinical variables and subtype assignment. The odds ratio test using dichotomized variables was conducted to investigate relationships between different subtyping schemes. The MATLAB package (Mathworks, Natick, MA, USA) and the R package (v.3.1 http://www.r-project.org/) were used for all statistical tests.

RESULTS

A prostate cancer gene expression atlas

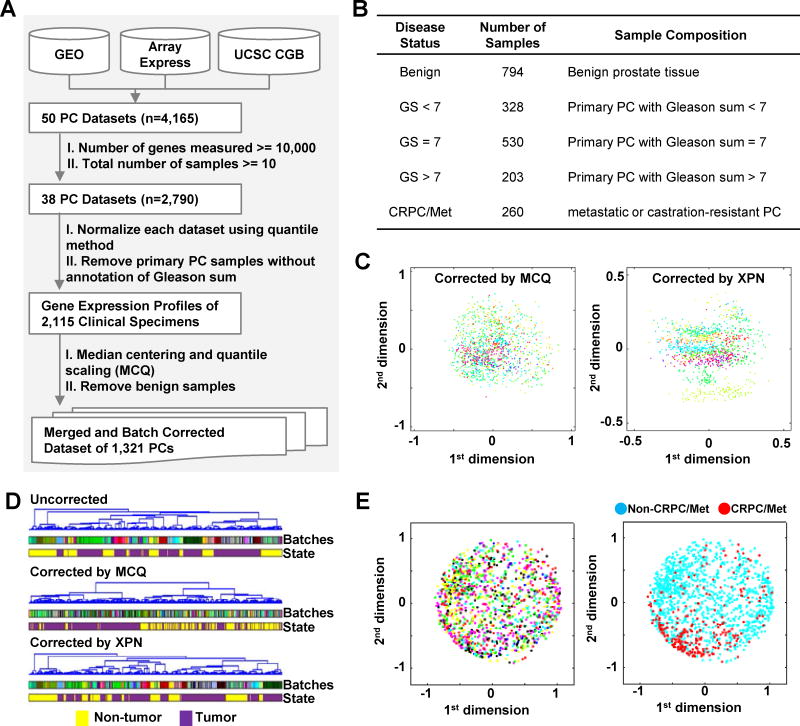

To achieve adequate power for a robust molecular classification of PC, we initially collected 50 PC datasets from three public databases: Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo), ArrayExpress (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress), and the UCSC Cancer Genomics Browser (https://genome-cancer.ucsc.edu) and selected 38 datasets (Supplementary Table S1), in which the numbers of samples are larger than 10 and where over 10,000 genes were measured (Fig. 1A). This collection contains datasets consisting of 2,790 expression profiles of benign prostate tissue, primary tumors, and metastatic or castration-resistant PC (CRPC/Met) (Fig. 1B). We then removed a subset of samples with ambiguous clinical information and generated a single merged dataset by cross study normalization, based on median-centering and the quantile normalization method (MCQ) (18). The merged dataset consists of 1,321 tumor specimens that we named the Discovery (DISC) cohort. The merged gene expression profiles showed a significant reduction of systematic, dataset-specific bias in comparison to the same dataset corrected by the XPN method, which is also used for merging data from different platforms (20) (Fig. 1C). Biological differences between tumors and benign tissues were also maintained while minimizing batch effects (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1.

Integration of PC transcriptome and quality control. A. Schematic showing the process of collecting and merging PC transcriptomes. B. Clinical composition of 2,115 PC cases. C. MDS of merged expression profiles after MCQ or XPN correction in the DISC cohort. Dots with different colors represent different batches or datasets. D. Hierarchical clustering illustrates the sample distribution of uncorrected (upper), corrected by MCQ (middle), and corrected by XPN (lower). Different colors on ‘Batches’ rows represent different batches or datasets from the individual studies. E. MDS of pathway activation profiles in the DISC cohort shows distribution of the samples from same batches. Dots with different colors represent different batches or datasets.

As validation datasets, we assembled another collection of 12 independent cohorts consisting of 2,728 tumors from primary and CRPC/Met samples (Table 1). From this collection, 3 datasets, the Swedish watchful waiting cohort (SWD), the Emory cohort (EMORY), and the Health Study Prostate Tumor cohort (HSPT), were obtained from GEO. The gene expression profiles and clinical annotations of The Cancer Gnome Atlas (TCGA) cohort of 333 PC and SU2C/PCF Dream Team cohort (SU2C) of 118 CRPC/Mets were obtained from cBioPortal (http://www.cbioportal.org/). Seven additional cohorts were obtained from the Decipher GRID™ database (GRID). The expression datasets from the GRID were generated using a single platform, the Affymetrix Human Exon 1.0 ST Array, using primary tumors for the purpose of developing outcomes and treatment response signatures. We used these 7 cohorts to investigate associations of clinical outcomes with subtype assignment in this study.

Table 1.

List of independent cohorts for validation of the subtypes. OS: overall survival; PMS: progression to metastatic state; TMP: time to metastatic progression; PCSM: PC-specific mortality.

| Cohort Name | Number of Samples | Disease Status | Available Clinical Outcomes | Data from GRID™ | Abbreviation | PubMed ID. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Swedish Watchful-Wainting Cohort | 281 | Localized | OS | No | SWD | 20233430 |

| The Cancer Genome Anatomy | 333 | Localized | N.A. | No | TCGA | 26000489 |

| Emory University | 106 | Localized | N.A. | No | EMORY | 24713434 |

| Health Professionals Follow-up Study and Physicians' Health Study Prostate Tumor Cohort | 264 | Localized | N.A. | No | HSPT | 25371445 |

| Stand Up To Cancer/Prostate Cancer Foundation Dream Team Cohort | 118 | CRPC/Met | N.A. | No | SU2C | 26000489 |

| Mayo Clinic Cohort 1 | 545 | Localized | PMS, TMP, PCSM | Yes | MAYO1 | 23826159 |

| Mayo Clinic Cohort 2 | 235 | Localized | PMS, TMP, PCSM | Yes | MAYO2 | 23770138 |

| Thomas Jefferson University cohort | 130 | Localized | PMS, TMP, PCSM | Yes | TJU | 25035207 |

| Cleveland Clinic Foundation Cohort | 182 | Localized | PMS, TMP, PCSM | Yes | CCF | 25466945 |

| Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center cohort | 131 | Localized | PMS, PCSM | Yes | MSKCC | 20579941 |

| Erasmus Medical Centre Cohort | 48 | Localized | PMS, PCSM | Yes | EMC | 23319146 |

| Johns Hopkins Medicine Cohort | 355 | Localized | PMS, TMP, PCSM | Yes | JHM | 25466945 |

N.A.: Not Available

Pathway activations describing PC biology

Recent studies have demonstrated the advantage of pathway-based analysis in clinical stratification for prostate and other cancer types (10,26,27), However, to date there has been no study of PC using pathway activation profiles in which thousands of patient specimens were used. In addition, the utility of recently characterized molecular lesions such as AR amplification/overexpression, AR-V expression, transcriptional activation of EZH2 and forkhead box A1 (FOXA1), and SPOP mutation have not been fully exploited for classification. Therefore, we employed 22 pathway activation gene expression signatures encompassing PC-relevant signaling and genomic alterations (Supplementary Table S2 and Supplementary Table S3) in the DISC cohort (n=1,321). These were ultimately collapsed into 14 pathway signatures that were grouped into 3 categories: 1) PC-relevant signaling pathways, including activation of AR, AR-V, EZH2, FOXA1, and rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (RAS) and inactivation by polycomb repression complex 2 (PRC); 2) genetic and genomic alterations, including mutation of SPOP, TMPRSS2–ERG fusion (ERG), and deletion of phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN); and 3) biological features related to aggressive PC progression, including stemness (ES), cell proliferation (PRF), epithelial-mesenchymal transition (MES), pro-neural (PN), and aggressive PC with neuroendocrine differentiation (AV). Pathway activation scores were computed in each specimen in the DISC cohort using the Z-score method (22). The conversion of gene expression to pathway activation showed a further reduction of batch effects, while preserving biological differences that are particularly evident in the clustering of metastatic and non-metastatic samples (Fig. 1E).

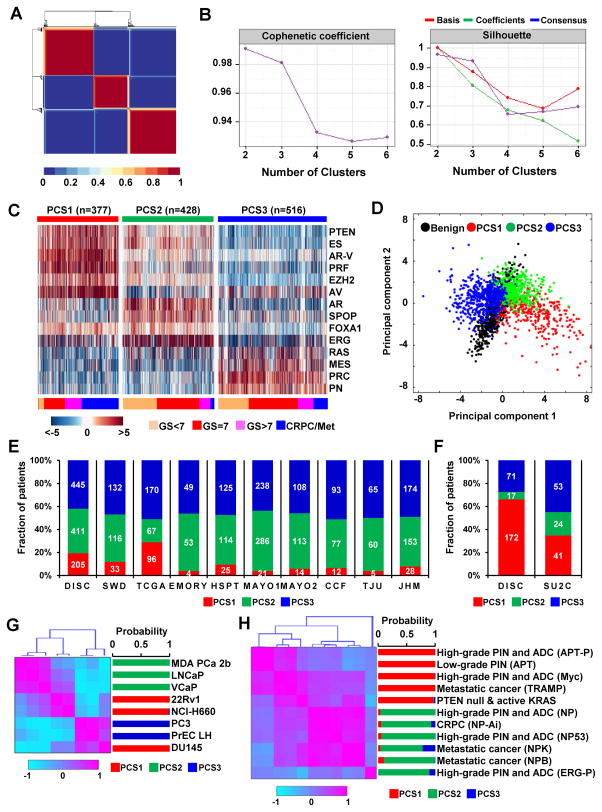

Identification and validation of molecular subgroups

We performed unsupervised clustering based on consensus NMF clustering (24) using the 14 pathway activation profiles in the DISC cohort. A consensus map of the NMF clustering results shows clear separation of the samples into three clusters (Fig. 2A). To identify the optimal number of clusters and to assess robustness of the clustering result, we computed the cophenetic coefficient and silhouette score using different numbers of clusters (2 to 6). These results indicate that 3 clusters is a statistically optimal representation of the data (Fig. 2B). A heatmap of 3 sample clusters demonstrates highly consistent pathway activation patterns within each group (Fig. 2C). These analyses suggest that the clusters correspond to 3 PC subtypes. We compared the magnitude of activation of each pathway across the 3 clusters evident in Fig. 2C using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for pairwise comparisons (Supplementary Fig. S1). The PCS1 subtype exhibits high activation scores for EZH2, PTEN, PRF, ES, AV, and AR-V pathways. In contrast, ERG pathway activation predominates in PCS2, which is also characterized by high activation of AR, FOXA1, and SPOP. PCS3 exhibits high activation of RAS, PN, MES, while AR and AR-V activation are low.

Figure 2.

Identification and validation of novel PC subtypes. A. Consensus matrix depicts robust separation of tumors into 3 subtypes. B. Changes of cophenetic coefficient and silhouette score at rank 2 to 6. C. Pathway activation profiles of 1,321 tumors defines 3 PC subtypes. D. Score plot of principal component analysis for benign and 3 subtypes. E and F. The 3 subtypes were recognized in 10 independent cohorts. G and H. Correlation of pathway activation profiles in 8 PC cell lines from the CCLE and 11 PC mouse models and probability from the pathway classifier.

High enrichment of PRC and low AR within PCS3 raises the question of whether this subtype is an artifact of contaminating non-tumor tissues. However, principal component analysis demonstrates that samples in PCS3 are as distinct from benign tissues as samples in the other subtypes (Fig. 2D). To further confirm the difference from benign tissue, we made use of a gene signature shown to discriminate benign prostate tissue from cancer in a previous study (28) and found a significant difference (P<0.001) in all the tumors in the subtypes compared to benign tissues (Supplementary Fig. S2). These results demonstrate that PCs retain distinct gene expression profiles between subtypes, which are not related to the amount of normal tissue contamination.

To validate the PCS classification scheme, a 14-pathway classifier was developed using a naïve Bayes machine learning algorithm (see details in Method). This classifier was applied to 9 independent cohorts of localized tumors (i.e. SWD, TCGA, EMORY, HSPT, MAYO1/2, CCF, TJU, and JHM) and the SU2C cohort of CRPC/Met tumors. Out of these 10 independent cohorts, 5 cohorts (i.e., MAYO1/2, TJU, CCF, and JHM) were from the GRID (Fig. 2E and Table 1) (29). The 14-pathway classifier reliably categorized tumors in the DISC cohort into 3 subtypes, with an average classification performance = 0.89 (P<0.001). The 3 subtypes were identified in all cohorts. Their proportions were similar across the localized disease cohorts, demonstrating the consistency of the classification algorithm across multiple practice settings (Fig. 2E). The 2 cohorts consisting of CRPC/Met tumors (DISC and SU2C) showed some differences in the frequency of PCS1 and PCS3; the most frequent subtype in the DISC CRPC/Met cohort was PCS1 (66%), while the most frequent subtype in SU2C was PCS3 (45%) (Fig. 2F). PCS2 was the minor subtype in both CRPC/Met cohorts.

To determine if the PCS classification is relevant to laboratory models of PC, we analyzed 8 human PC cell lines from The Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) (GSE36133) (30) and 11 PC mouse models (31,32). There are two datasets for mouse models. The first dataset (GSE53202) contains transcriptome profiles of 13 genetically-engineered mouse models, including: normal epithelium (i.e., wild-type), low-grade PIN (i.e., Nkx3.1 and APT), high-grade PIN and adenocarcinoma (i.e., APT-P; APC; Myc; NP; Erg-P; and NP53), castration-resistant PC (i.e., NP-Ai), and metastatic PC (i.e., NPB; NPK; and TRAMP). Because of no available data for samples without drug treatment, the Nkx3.1 and APC models were excluded from this analysis. The second dataset (GSE34839) contains transcriptome profiles from mice with PTEN-null/KRAS activation mutation-driven high grade, invasive PC and mice with only the PTEN-null background. This analysis revealed that all 3 PC subtypes were represented in the 8 human PC cell lines (Fig. 2G), while only 2 subtypes (PCS1 and PCS2) were represented in the mouse models (Fig. 2H). This result provides evidence that the subtypes are recapitulated in genetically engineered mouse models and persist in human cancer cells in cell culture.

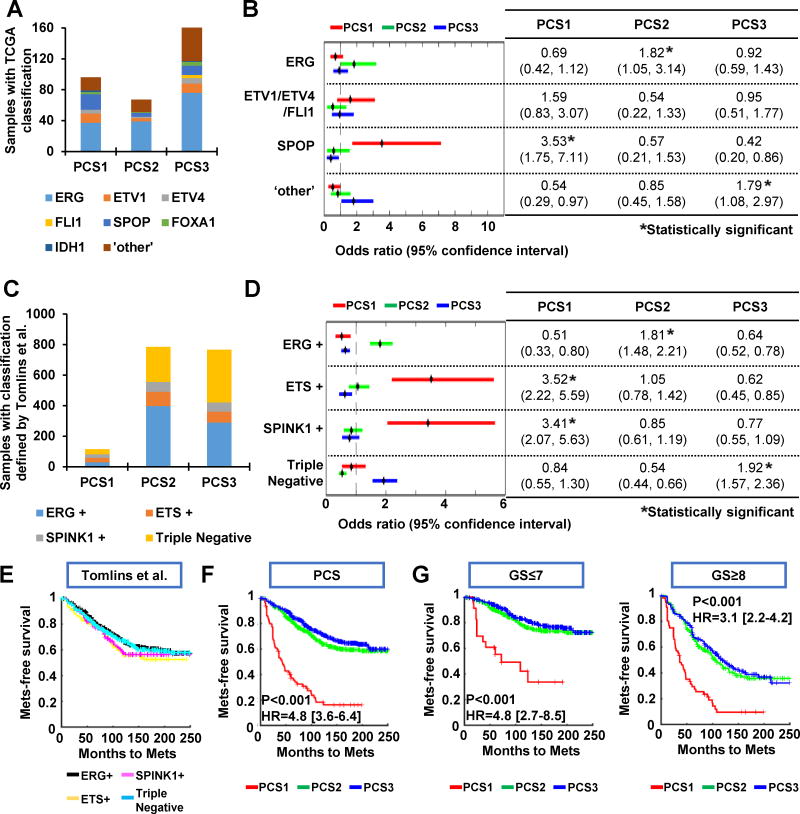

Evaluation of PCS subtypes in comparison with other subtypes

Several categorization schemes of PC have been described, based mostly on tumor-specific genomic alterations and in some cases with integration of transcriptomic and other profiling data (10,29,33). This prompted us to compare the PCS classification scheme with the genomic subtypes derived by TCGA (34), because comprehensive genomic categorization was recently made available (35). We also compared the PCS classification with the subtypes recently defined by Tomlins et al. from RNA expression data (29). The Tomlins subtyping scheme is defined using the 7 GRID cohorts (i.e., MAYO1/2, TJU, CCF, MSKCC, EMC, and JHM) that we used for validating the PCS system. The large number of cases in the 7 GRID cohorts (n=1,626) is comparable to our DISC cohort in terms of heterogeneity and complexity. TCGA identified several genomic subtypes, named ERG, ETV1, ETV4, FLI1, SPOP, FOXA1, IDH1, and ‘other’. Tomlins et al. described 4 subtypes based on microarray gene expression patterns that are related to several genomic aberrations (i.e., ERG+, ETS+, SPINK1+, and Triple Negative (ERG-/ETS-/SPINK1-)).

A comparison of the PCS categories with the TCGA genomic subtypes showed that the tumors classified as ERG, ETV1/4, SPOP, FOXA1, and ‘other’ were present across all the PCS categories in the TCGA dataset (n=333) (Fig. 3A). SPOP cancers were enriched in PCS1 [odds ratio: 3.53], while PCS2 tumors were over-represented in TCGA/ERG cancers [odds ratio: 1.82] and TCGA/‘other’ cancers were enriched in PCS3 [odds ratio: 1.79] (Fig. 3B). In the GRID cohorts, we observed all PCS categories in all classification groups as defined by Tomlins et al. (Fig. 3C and D). We found a high frequency of the Tomlins/ERG+ subtype in PCS2, but not in PCS1. PCS1 was enriched for Tomlins/ETS+ and Tomlins/SPINK1+ subtypes, while PCS3 was enriched for the Triple Negative subtype but not the ERG+ or ETS+ subgroups. Finally, we compared the Tomlins classification method with the PCS classification using 5 out of 7 GRID cohorts. PCS1 demonstrated significantly shorter metastasis-free survival compared to PCS2 and PCS3 (P<0.001) (Fig. 3E). In contrast, no difference in metastatic progression was seen among the Tomlins categories (Fig. 3F).

Figure 3.

Comparison of the PCS subtypes with previously described subtypes. A. Distribution of TCGA tumors (n=333) using the PCS subtypes compared to TCGA subtypes. B. Relationship between PCS subtyping and TCGA subtypes. C. Distribution of GRID tumors (n=1,626) using PCS categories compared to Tomlins subtypes. D. Relationship between PCS subtyping and Tomlins subtypes. E and F. Association of metastasis-free survival using Tomlins subtypes and using the PCS subtypes in the GRID tumors. G. Metastasis-free survival in tumors of GS≤7 (left) and GS≥8 (right).

PCS1 contained the largest number of PCs with GS≥8 (Fig. 2C). Given the overall poorer outcomes seen in PCS1 tumors, we tested whether this result was simply a reflection of the enrichment of high-grade disease in this group (i.e., GS≥8). For this analysis, we merged 5 GRID cohorts (i.e., MAYO1/2, TJU, CCF, and JHM) into a single dataset and separately analyzed low and high-grade disease. We observed a similarly significant (P<0.001) association between subtypes and metastasis-free survival in GS≤7 and in GS≥8 (Fig. 3G). Thus, tumors in the PCS1 group exhibit the poorest prognosis, including in tumors with low Gleason sum score. Finally, in the DISC cohort, although CRPC/Met tumors were present in all PCS categories, PCS1 predominated (66%), followed by PCS3 (27%) and PCS2 (7%) tumors. To confirm whether this clinical correlation is replicated in individual cohorts, we also assessed association with time to metastatic progression, PC-specific mortality (PCSM), and overall survival (OS) in 5 individual cohorts in the GRID (i.e. MAYO1/2, CCF, TJU, and JHM) and in the SWD cohorts. PCS1 was seen to be the most aggressive subtype, consistent with the above results (Supplementary Fig. S3).

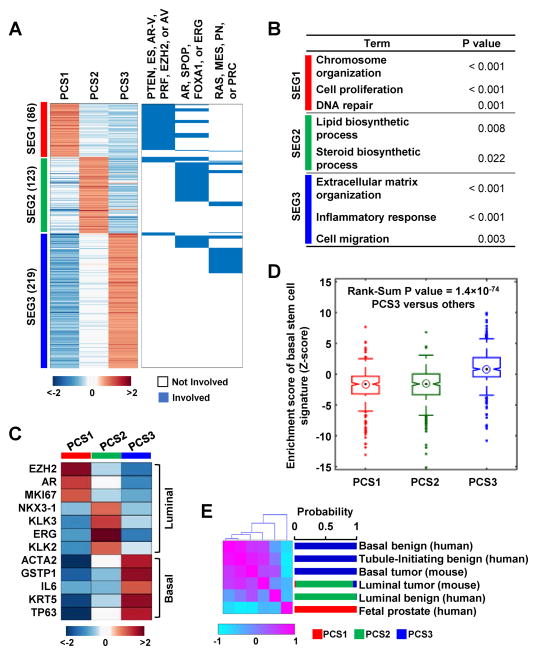

PCS categories possess characteristics of basal and luminal prostate epithelial cells

PC may arise from oncogenic transformation of different cell types in glandular prostate epithelium (36–38). Breast cancers can be categorized into luminal and basal subtypes, which are associated with different patient outcomes (39). It is unknown whether this concept applies to human PC. To examine whether the 3 PCS categories are a reflection of different cell types, we identified 428 subtype-enriched genes (“SEG”1–3; 86 for PCS1, 123 for PCS2, and 219 for PCS3; Supplementary Table S4) in each subtype. As expected, these genes are involved in pathways that are enriched in each subtype (Fig. 4A) and which define the perturbed cellular processes of the subtype. We then identified the cellular processes that are associated with the SEGs. Proliferation and lipid/steroid metabolism are characteristic of SEG1 and SEG2, while extracellular matrix organization, inflammation, and cell migration are characteristic of SEG3 (Fig. 4B). This result suggests that distinct biological functions are associated with the PCS categories.

Figure 4.

Genes enriched in each of the 3 subtypes are associated with luminal and basal cell features. A. Relative gene expression (left) and pathway inclusion (right) of SEGs are displayed. B. Cellular processes enriched by each of the 3 SEGs (P<0.05). C. Expression of the luminal and basal markers in the 3 subtypes. D. Enrichment of basal stem cell signature. E. Correlation of pathway activities between samples from human and mouse prostate (left) and probability from the pathway classifier (right).

To determine whether the PCS categories reflect luminal or basal cell types of the prostatic epithelium, we analyzed the mean expression of genes known to be characteristic of luminal (EZH2, AR, MKI67, NKX3-1, KLK2/3, and ERG) or basal (ACTA2, GSTP1, IL6, KRT5, and TP63) prostatic cells (Fig. 4C). We observed a strong association (FDR<0.001; fold change>1.5) between luminal genes and PCS1 and PCS2, and basal genes and PCS3. To verify this observation, we used 2 independent datasets derived from luminal and basal cells from human (40) and mouse (GSE39509) (37) prostates. The assignment of a basal designation to PCS3 is further supported by the highly significant enrichment in PCS3, in comparison to the other 2 subtypes, of a recently described prostate basal cell signature derived from CD49f-Hi versus CD49f-Lo benign and malignant prostate epithelial cells (Fig. 4D) (41). In addition, using the 14-pathway classifier, mouse basal tumors and human basal cells from benign tissues were classified as PCS3, while mouse luminal tumors and benign prostate human luminal cells were classified into PCS2 (Fig. 4E). These results are consistent with the conclusion that the PCS categories can be divided into luminal and basal subtypes.

A gene expression classifier for assignment to subtypes

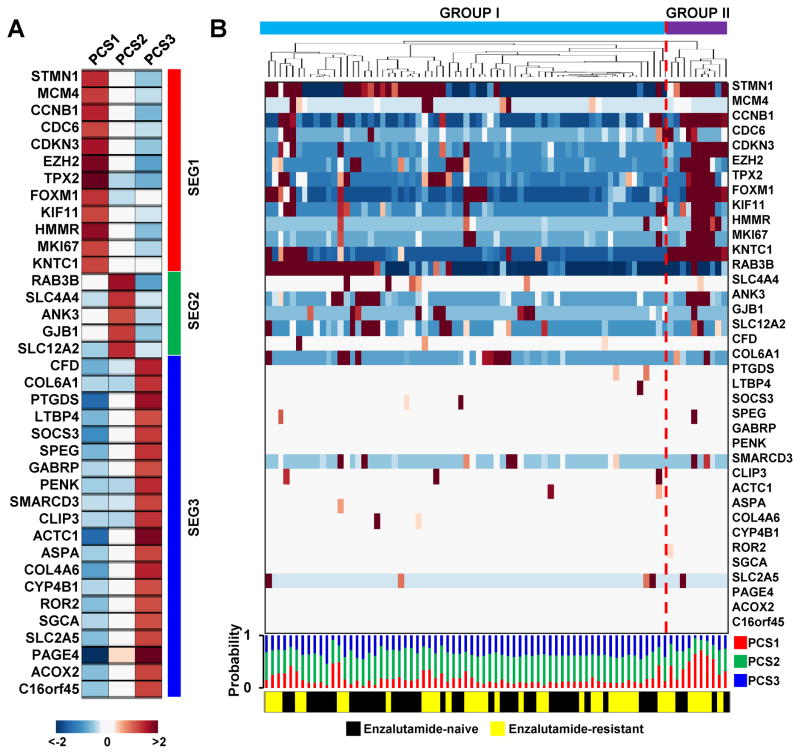

Given the potential advantages of the PCS system to classify tumor specimens, we constructed a classifier that can be applied to an individual patient specimen in a clinical setting (Supplementary Fig. S4A). First, out of 428 SEGs, 93 genes were selected on the basis of highly consistent expression patterns in 10 cohorts (i.e. SWD, TCGA, EMORY, HSPT, SU2C, MAYO1/2, CCF, TJU, and JHM). Second, using a random forest machine learning algorithm, we selected 37 genes with feature importance scores >0.5, showing a comparable level of error with the full model based on 428 SEGs (Supplementary Fig. S4B). Performance of the classifier was assessed in the GRID cohort (AUC=0.97). The 37-gene panel displays significantly different expression patterns between the 3 subtypes in the DISC cohort (Fig. 5A).

Figure 5.

A 37-gene classifier employed in patient tissues and CTCs. A. Heatmap displays the mean expression pattern of the 37 gene panel in the 3 subtypes from the DISC cohort. B. Hierarchical clustering of 77 CTCs obtained from CRPC patients by gene expression of the 37-gene panel. Barplot in the bottom displays probability of PCS assignment from application of the classifier.

The robust performance of the gene panel led us to determine whether it could be used to profile circulating tumor cells (CTCs) from patients with CRPC. We analyzed single cell RNA sequencing data from 77 intact CTCs isolated from 13 patients (42). Prior to the clustering analysis to investigate the expression patterns of these CTC data, the normalized read counts as read-per-million (RPM) mapped reads were transformed on a log2-scale for each gene. The 77 CTCs were largely clustered into two groups using median-centered expression profiles corresponding to the 37 gene PCS panel by the hierarchical method (Fig. 5B). One group (GROUP I), consisting of 67 CTCs displays low expression of PCS1 enriched genes, while the other group (GROUP II) consisting of 10 CTCs has high expression of PCS1 enriched genes. In addition, we observed that PCS3 enriched genes in the panel were not detected or have very low expression changes across all CTCs as shown in the heatmap of Fig. 5B. The results suggest that CTCs can be divided into two groups with the 37 PCS panel. Given this result, we hypothesized that the 37-gene classifier might assign CTCs to PCS1 or PCS2, consistent with the clustering result. The bar graph below the heatmap illustrates the probability of likelihood of PCS assignment, with the result that all the CTCs were assigned to PCS1 (n=12) or PCS2 (n=65), while no PCS3 CTCs were assigned based on the largest probability score. By comparing with the CTC group assignment, 7 (70%) out of 10 CTCs in the GROUP II were assigned to PCS1 by the 37-gene classifier and 62 (95%) out of 65 CTCs in the GROUP I were assigned to PCS2 by the classifier. We then tested whether GROUP I and II exhibit any difference in terms of therapeutic responses. Of note, 5 out of the 7 CTCs in GROUP II [odds ratio: 1.74; 95% confidence interval: 0.49–6.06] were from patients whose cancer exhibited radiographic and/or PSA progression during enzalutamide therapy, suggesting that the 37 gene PCS panel can potentially identify patients with resistance to enzalutamide therapy.

Collectively, the results demonstrate that the 37-gene classifier has a potential to assign individual PCs to PCS1 using both prostate tissues and blood CTCs, suggesting that the classifier can be applied to subtype individual PCs using clinically relevant technology platforms (43,44), including by noninvasive methods.

DISCUSSION

In this study we describe a novel classification system for PC, based on an analysis of over 4,600 PC specimens, which consists of only 3 distinct subtypes, designated PCS1, PCS2 and PCS3. PCS1 exhibits the highest risk of progression to advanced disease, even for low Gleason grade tumors. Although sampling methods across the cohorts we studied were different, classification into the 3 subtypes was reproducible. For example, the SWD cohort consists of specimens that were obtained by transurethral resection of the prostate rather than radical prostatectomy; however, subtype assignment and prognostic differences between the subtypes were similar to the other cohorts we examined (Supplementary Fig. S3J). Genes that are significantly enriched in the PCS1 category were highly expressed in the subset of CTCs (58%, 7 CTCs out of 12) from patients with enzalutamide-resistant tumors. This proportion of resistant cases in PCS1 CTCs is very high compared to PCS2 CTCs (8%, 5 CTCs out of 65). The characteristics of the PCS categories are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of PCS characteristics.

| Sample Type | Features | PCS1 | PCS2 | PCS3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Tumors | Proportion | 6% | 47% | 47% |

| Pathology | Enriched GS≥8 | Enriched GS≤7 | Enriched GS≤7 | |

| Prognosis | Poor | Variable | Variable | |

| Subtypes- TCGA | SPOP | ERG | ‘other’ | |

| Subtypes- Tomlins | ETS+, SPINK+ | ERG+ | Triple Negative | |

| Pathway signatures | AR-V, ES, PTEN, PRF, EZH2, NE | AR, FOXA1, SPOP, ERG | PRC, RAS, PN, MES | |

| Cell lineage | Luminal-like | Luminal-like | Basal-like | |

|

| ||||

| Patient CTCs | Proportion | 16% | 84% | 0% |

| Enzalutamide Resistance | Yes (58%) | No (8%) | unknown | |

Previously published PC classifications have defined subtypes largely based on the presence or absence of genomic alterations (e.g., TMPRSS2-ERG translocations). Tumors with ERG rearrangement (ERG+) are overrepresented in PCS2, however it is not the presence or absence of an ERG rearrangement that defines the PCS2 subtype, but rather ERG pathway activation features based on coordinate expression levels of genes in the pathway. Our findings provide evidence for biologically distinct forms of PC that are independent of Gleason grade, currently the gold standard for clinical decision-making. In addition, by comparing prognostic profiles between the PCS categories and the Tomlins et al. categories, prognostic information was evident only from the PCS classification scheme in the same cohort. Taken together, this indicates that the PCS classification is unique.

Although the present report has provided evidence that PCS classification can assign subtypes within groups of “indolent” as well as aggressive tumors, and in a wide range of preclinical models, it remains to be determined whether the PCS categories might be stable during tumor evolution in an individual patient. An interesting alternative possibility is that disease progression results in phenotypic diversification with respect to the PCS assignment. We have shown that pre-clinical model systems, including genetically-engineered mouse models (GEMMs), can be assigned with high statistical confidence to the PCS categories. We believe the simplest explanation for this finding is that these subtypes reflect distinct epigenetic features of chromatin that are potentially stable, even in the setting of genomic instability associated with advanced disease. This possibility needs to be formally tested. The human PC cell lines we evaluated could be assigned to all 3 subtypes; however, the GEMMs we tested could only be assigned to PCS1 and PCS2. This finding suggests that approximately 1/3 of human PCs are not being modeled in widely used GEMMs. It should be feasible to generate mouse models for PCS3 through targeted genetic manipulation of pathways that are deregulated in PCS3 and through changing chromatin structure, such as by altering the activity of the PRC2 complex.

A major clinical challenge remains the early recognition of aggressive disease, in particular due to the multifocal nature of PC (45). The classification scheme we describe predicts the risk of progression to lethal PC in patients with a diagnosis of low-grade localized disease (Fig 3G). It is possible that in these cancers, pathway activation profiles are independent of Gleason grade and that pathways indicating high risk of progression are manifested early in the disease process and throughout multiple cancer clones in the prostate. In addition to predicting the risk of disease progression, PCS subtyping might also assist with the selection of drug treatment in advanced cancer by profiling CTCs in patient blood. With the 37-gene classifier we present here, it will be possible to assign individual tumors to PCS categories in a clinical setting. This new classification method may provide novel opportunities for therapy and clinical management of PC.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from NIH (R01DK087806, R01CA143777, G20 RR030860, and 2P01 CA098912), the Department of Defense PCRP (W81XWH-14-1-0152; W81XWH-14-1-0273), the Urology Care Foundation Research Scholars Program, the Prostate Cancer Foundation Creativity Award, the Jean Perkins Foundation, and the Spielberg Family Discovery Fund. The authors are grateful to Drs. Francesca Demichelis, Felix Feng, and Benjamin Berman for helpful discussions during the course of this study.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest: N. Erho is a bioinformatics group lead at GenomeDx Biosciences Inc. M. Alshalalfa is a bioinformatician at GenomeDx Biosciences Inc. H. Al-deen Ashab is a data scientist at Genomedx Biosciences Inc. E. Davicioni has ownership interest (including patents) in GenomeDx Biosciences Inc. R.J. Karnes reports receiving other commercial research support from GenomeDx Biosciences Inc. E.A. Klein has received speakers bureau honoraria from GenomeDx Biosciences Inc. A.E. Ross has ownership interest (including patents) in GenomeDx Biosciences Inc. Mandeep Takhar is a bioinformatician at GenomeDX. No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed by the other authors.

References

- 1.Perner S, Demichelis F, Beroukhim R, Schmidt FH, Mosquera JM, Setlur S, et al. TMPRSS2:ERG fusion-associated deletions provide insight into the heterogeneity of prostate cancer. Cancer research. 2006;66(17):8337–41. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tomlins SA, Laxman B, Dhanasekaran SM, Helgeson BE, Cao X, Morris DS, et al. Distinct classes of chromosomal rearrangements create oncogenic ETS gene fusions in prostate cancer. Nature. 2007;448(7153):595–9. doi: 10.1038/nature06024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh D, Febbo PG, Ross K, Jackson DG, Manola J, Ladd C, et al. Gene expression correlates of clinical prostate cancer behavior. Cancer cell. 2002;1(2):203–9. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00030-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lapointe J, Li C, Higgins JP, van de Rijn M, Bair E, Montgomery K, et al. Gene expression profiling identifies clinically relevant subtypes of prostate cancer. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101(3):811–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0304146101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taylor BS, Schultz N, Hieronymus H, Gopalan A, Xiao Y, Carver BS, et al. Integrative genomic profiling of human prostate cancer. Cancer cell. 2010;18(1):11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grasso CS, Wu YM, Robinson DR, Cao X, Dhanasekaran SM, Khan AP, et al. The mutational landscape of lethal castration-resistant prostate cancer. Nature. 2012;487(7406):239–43. doi: 10.1038/nature11125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baca SC, Prandi D, Lawrence MS, Mosquera JM, Romanel A, Drier Y, et al. Punctuated evolution of prostate cancer genomes. Cell. 2013;153(3):666–77. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barbieri CE, Baca SC, Lawrence MS, Demichelis F, Blattner M, Theurillat JP, et al. Exome sequencing identifies recurrent SPOP, FOXA1 and MED12 mutations in prostate cancer. Nature genetics. 2012;44(6):685–9. doi: 10.1038/ng.2279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tomlins SA, Mehra R, Rhodes DR, Cao X, Wang L, Dhanasekaran SM, et al. Integrative molecular concept modeling of prostate cancer progression. Nature genetics. 2007;39(1):41–51. doi: 10.1038/ng1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Markert EK, Mizuno H, Vazquez A, Levine AJ. Molecular classification of prostate cancer using curated expression signatures. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108(52):21276–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117029108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perou CM, Sorlie T, Eisen MB, van de Rijn M, Jeffrey SS, Rees CA, et al. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2000;406(6797):747–52. doi: 10.1038/35021093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cancer Genome Atlas Research N. Comprehensive genomic characterization defines human glioblastoma genes and core pathways. Nature. 2008;455(7216):1061–8. doi: 10.1038/nature07385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choudhury AD, Eeles R, Freedland SJ, Isaacs WB, Pomerantz MM, Schalken JA, et al. The role of genetic markers in the management of prostate cancer. European urology. 2012;62(4):577–87. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.05.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharma NL, Massie CE, Ramos-Montoya A, Zecchini V, Scott HE, Lamb AD, et al. The androgen receptor induces a distinct transcriptional program in castration-resistant prostate cancer in man. Cancer cell. 2013;23(1):35–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Watson PA, Arora VK, Sawyers CL. Emerging mechanisms of resistance to androgen receptor inhibitors in prostate cancer. Nature reviews Cancer. 2015;15(12):701–11. doi: 10.1038/nrc4016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu K, Wu ZJ, Groner AC, He HH, Cai C, Lis RT, et al. EZH2 oncogenic activity in castration-resistant prostate cancer cells is Polycomb-independent. Science. 2012;338(6113):1465–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1227604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blattner M, Lee DJ, O'Reilly C, Park K, MacDonald TY, Khani F, et al. SPOP mutations in prostate cancer across demographically diverse patient cohorts. Neoplasia. 2014;16(1):14–20. doi: 10.1593/neo.131704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.You S, Cho CS, Lee I, Hood L, Hwang D, Kim WU. A systems approach to rheumatoid arthritis. PloS one. 2012;7(12):e51508. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bolstad BM, Irizarry RA, Astrand M, Speed TP. A comparison of normalization methods for high density oligonucleotide array data based on variance and bias. Bioinformatics. 2003;19(2):185–93. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shabalin AA, Tjelmeland H, Fan C, Perou CM, Nobel AB. Merging two gene-expression studies via cross-platform normalization. Bioinformatics. 2008;24(9):1154–60. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Piccolo SR, Sun Y, Campbell JD, Lenburg ME, Bild AH, Johnson WE. A single-sample microarray normalization method to facilitate personalized-medicine workflows. Genomics. 2012;100(6):337–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levine DM, Haynor DR, Castle JC, Stepaniants SB, Pellegrini M, Mao M, et al. Pathway and gene-set activation measurement from mRNA expression data: the tissue distribution of human pathways. Genome biology. 2006;7(10):R93. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-10-r93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carrasco DR, Tonon G, Huang Y, Zhang Y, Sinha R, Feng B, et al. High-resolution genomic profiles define distinct clinico-pathogenetic subgroups of multiple myeloma patients. Cancer cell. 2006;9(4):313–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brunet JP, Tamayo P, Golub TR, Mesirov JP. Metagenes and molecular pattern discovery using matrix factorization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101(12):4164–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308531101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Storey JD. A direct approach to false discovery rates. J Roy Stat Soc B. 2002;64:479–98. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gatza ML, Silva GO, Parker JS, Fan C, Perou CM. An integrated genomics approach identifies drivers of proliferation in luminal-subtype human breast cancer. Nature genetics. 2014;46(10):1051–9. doi: 10.1038/ng.3073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Drier Y, Sheffer M, Domany E. Pathway-based personalized analysis of cancer. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110(16):6388–93. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219651110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stuart RO, Wachsman W, Berry CC, Wang-Rodriguez J, Wasserman L, Klacansky I, et al. In silico dissection of cell-type-associated patterns of gene expression in prostate cancer. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101(2):615–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2536479100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tomlins SA, Alshalalfa M, Davicioni E, Erho N, Yousefi K, Zhao S, et al. Characterization of 1577 Primary Prostate Cancers Reveals Novel Biological and Clinicopathologic Insights into Molecular Subtypes. European urology. 2015;68(4):555–67. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.04.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barretina J, Caponigro G, Stransky N, Venkatesan K, Margolin AA, Kim S, et al. The Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia enables predictive modelling of anticancer drug sensitivity. Nature. 2012;483(7391):603–7. doi: 10.1038/nature11003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aytes A, Mitrofanova A, Lefebvre C, Alvarez MJ, Castillo-Martin M, Zheng T, et al. Cross-species regulatory network analysis identifies a synergistic interaction between FOXM1 and CENPF that drives prostate cancer malignancy. Cancer cell. 2014;25(5):638–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mulholland DJ, Kobayashi N, Ruscetti M, Zhi A, Tran LM, Huang J, et al. Pten loss and RAS/MAPK activation cooperate to promote EMT and metastasis initiated from prostate cancer stem/progenitor cells. Cancer research. 2012;72(7):1878–89. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Erho N, Crisan A, Vergara IA, Mitra AP, Ghadessi M, Buerki C, et al. Discovery and validation of a prostate cancer genomic classifier that predicts early metastasis following radical prostatectomy. PloS one. 2013;8(6):e66855. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Electronic address scmo, Cancer Genome Atlas Research N. The Molecular Taxonomy of Primary Prostate Cancer. Cell. 2015;163(4):1011–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robinson D, Van Allen EM, Wu YM, Schultz N, Lonigro RJ, Mosquera JM, et al. Integrative clinical genomics of advanced prostate cancer. Cell. 2015;161(5):1215–28. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goldstein AS, Huang J, Guo C, Garraway IP, Witte ON. Identification of a cell of origin for human prostate cancer. Science. 2010;329(5991):568–71. doi: 10.1126/science.1189992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang ZA, Mitrofanova A, Bergren SK, Abate-Shen C, Cardiff RD, Califano A, et al. Lineage analysis of basal epithelial cells reveals their unexpected plasticity and supports a cell-of-origin model for prostate cancer heterogeneity. Nature cell biology. 2013;15(3):274–83. doi: 10.1038/ncb2697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baird AA, Muir TC. Membrane hyperpolarization, cyclic nucleotide levels and relaxation in the guinea-pig internal anal sphincter. British journal of pharmacology. 1990;100(2):329–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1990.tb15804.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Visvader JE. Keeping abreast of the mammary epithelial hierarchy and breast tumorigenesis. Genes & development. 2009;23(22):2563–77. doi: 10.1101/gad.1849509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu H, Cadaneanu RM, Lai K, Zhang B, Huo L, An DS, et al. Differential gene expression profiling of functionally and developmentally distinct human prostate epithelial populations. The Prostate. 2015;75(7):764–76. doi: 10.1002/pros.22959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith BA, Sokolov A, Uzunangelov V, Baertsch R, Newton Y, Graim K, et al. A basal stem cell signature identifies aggressive prostate cancer phenotypes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America; 2015; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miyamoto DT, Zheng Y, Wittner BS, Lee RJ, Zhu H, Broderick KT, et al. RNA-Seq of single prostate CTCs implicates noncanonical Wnt signaling in antiandrogen resistance. Science. 2015;349(6254):1351–6. doi: 10.1126/science.aab0917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Geiss GK, Bumgarner RE, Birditt B, Dahl T, Dowidar N, Dunaway DL, et al. Direct multiplexed measurement of gene expression with color-coded probe pairs. Nature biotechnology. 2008;26(3):317–25. doi: 10.1038/nbt1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morrison T, Hurley J, Garcia J, Yoder K, Katz A, Roberts D, et al. Nanoliter high throughput quantitative PCR. Nucleic acids research. 2006;34(18):e123. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martin NE, Mucci LA, Loda M, Depinho RA. Prognostic determinants in prostate cancer. Cancer journal. 2011;17(6):429–37. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e31823b042c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.