Abstract

We compared SenseWear Armband versions (v) 2.2 and 5.2 for estimating energy expenditure in healthy adults. Thirty-four adults (26 women), 30.1±8.7 years old, performed two trials that included light-, moderate-, and vigorous-intensity activities: 1) Structured routine: Seven activities performed for 8-min each, with 4-min of rest between activities; 2) Semi-structured routine: 12 activities performed for 5-min each, with no rest between activities. energy expenditure was measured by indirect calorimetry and predicted using SenseWear v2.2 and v5.2. Compared to indirect calorimetry (297.8±54.2 kcal), total energy expenditure was overestimated (P<0.05) by both SenseWear v2.2 (355.6±64.3 kcal) and v5.2 (342.6±63.8 kcal) during the structured routine. During the semi-structured routine, total energy expenditure for SenseWear v5.2 (275.2±63.0 kcal) was not different than indirect calorimetry (262.8±52.9 kcal), and both were lower (P<0.05) than v2.2 (312.2±74.5 kcal). Average mean absolute percent error was lower for the SenseWear v5.2 than for v2.2 (P<0.001). SenseWear v5.2 improved energy expenditure estimation for some activities (sweeping, loading/unloading boxes, walking), but produced larger errors for others (cycling, rowing). Although both algorithms overestimated energy expenditure as well as time spent in moderate-intensity physical activity (P<0.05), v5.2 offered better estimates than v2.2.

Keywords: Activity Monitor, Physical Activity, Assessment, Accelerometer, Calorimetry

Introduction

Accurate, reliable, convenient, and objective assessment of physical activity levels and energy expenditure in free-living individuals remains a challenging problem for epidemiologists, exercise scientists, behavioral researchers, and clinicians. Monitoring physical activity levels is important because regular physical activity is effective in the primary and secondary prevention of chronic diseases like cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer, hypertension, and osteoporosis (Warburton, Nicol, & Bredin, 2006). It is also an important component of weight management programs (Jakicic et al., 2001; Wing & Phelan, 2005).

The SenseWear Armband™ is a commercially available device that can estimate energy expenditure and physical activity levels. It combines data from a triaxial accelerometer and several heat sensors with demographic characteristics including gender, age, height, weight, and handedness in order to estimate energy expenditure utilizing proprietary algorithms developed by the manufacturer. The algorithms are periodically updated to improve energy expenditure estimation, which have been evaluated by a number of investigators (Benito et al., 2012; Berntsen et al., 2010; Brazeau et al., 2011; Drenowatz & Eisenmann, 2011; Erdogan, Cetin, Karatosun, & Baydar, 2010; Fruin & Rankin, 2004; King, Torres, Potter, Brooks, & Coleman, 2004; Lee, Kim, Bai, Gaesser, & Welk, 2014; Papazoglou et al., 2006; Smith, Lanningham-Foster, Welk, & Campbell, 2012; Van Hoye, Boen, & Lefevre, 2014; Welk, McClain, Eisenmann, & Wickel, 2007). The current commercially available software algorithm is the Innerview Research Software “SenseWear 8.1”, which uses algorithm version (v) 5.2. SenseWear v5.2 replaced v2.2 in 2014.

At the time of our investigation, we were aware of only three studies (Lee et al., 2014; Smith et al., 2012; Van Hoye et al., 2014) that examined the validity of SenseWear v5.2 for estimating energy expenditure when compared with the previous algorithm v2.2. In these studies, SenseWear v5.2 improved energy expenditure predictions over a wide range of activities in children (Lee et al., 2014) and over a limited range of activities in pregnant women (Smith et al., 2012). In young men and women, SenseWear v5.2 improved energy expenditure estimation compared to SenseWear v2.2 during walking and running in a hot (33° C) laboratory condition, but not in cooler conditions (19° C and 26° C) (Van Hoye et al., 2014). No studies have examined the validity of the current SenseWear v5.2 for predicting energy expenditure and estimating physical activity intensity levels in healthy adults across a wide range of physical activity intensities, including both steady-state and non-steady-state conditions. Moreover, no studies have compared the SenseWear v5.2 with the previous v2.2 in healthy adults, so it is unknown whether the newer algorithm provides better estimates of energy expenditure for different activities. It is recommended that direct comparisons of the newer accelerometer algorithms should be made with previous versions per best practice guidelines for accelerometer research (Welk, 2005). Therefore, the purpose of this study was to determine the validity of SenseWear v5.2 for estimating energy expenditure and physical activity intensity levels and to compare it with v2.2. We used indirect calorimetry (IC) as the criterion measure, and hypothesized that SenseWear v5.2 would produce better energy expenditure predictions than v2.2.

Methods

Participants

These data were collected as part of a larger National Institutes of Health funded project on physical activity monitoring devices (R01 HL091006). Study participants were 8 men and 26 women (see Table 1 for participant characteristics). Participants were excluded if they answered “yes” to any of the questions in the Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (Chisholm, Collis, Kulak, Davenport, & Gruber, 1975). Height was measured using a stadiometer. Weight and body composition were measured using the Bod Pod (Cosmed, Rome, Italy). All participants were nonsmokers and were not taking any medications for hypertension, diabetes, heart disease, or hyperlipidemia. The study was approved by the Arizona State University institutional review board and all participants provided written informed consent.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics (Means ± SD)

| All | Men | Women | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 34 | 8 | 26 |

| Age (years) | 30.1 ± 8.7 | 27.9 ± 7.2 | 30.8 ± 9.2 |

| Height (cm) | 165.7 ± 8.8 | 174.8 ± 5.7 | 162.9 ± 7.6 |

| Weight (kg) | 72.2 ± 16.8 | 84.4 ± 21.6 | 68.4 ± 13.4 |

| BMI (kg.m−2) | 26.2 ± 5.1 | 27.6 ± 6.9 | 25.7 ± 4.5 |

| Body Fat (%) | 30.6 ± 10.2 | 24.6 ± 13.9 | 32.5 ± 8.3 |

| Lean body mass (kg) | 49.1 ± 9 | 61.5 ± 6.4 | 45.3 ± 5.5 |

Physical Activity Routines

All participants underwent two physical activity routines, one structured and the other semi-structured. The activities, described in Table 2, were selected from a list established using metabolic equivalents (METs) from the Compendium of Physical Activity (Ainsworth et al., 2011). For both routines, participants were instructed to consume only water for at least 3 hours prior to ensure that resting oxygen uptake (V̇O2) was not affected by the thermic effect of food (Segal & Gutin, 1983; Segal, Gutin, Nyman, & Pi-Sunyer, 1985).

Table 2.

List of activities in the structured and semi-structured routines

| Structured Routine | Semi-Structured Routine | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sedentary/light-intensity | Moderate-intensity | Vigorous-intensity | |

| 1. Loading/ unloading boxesa | 1. Seated rest | 1. Sweeping | 1. Running 2.24 m·s−1 |

| 2. Sweeping | 2. Typing | 2. Vacuuming | 2. Running 2.46 m·s−1 |

| 3. Cycling at 50 Wb | 3. Ironing clothes | 3. Walking at 1.12 m·s−1 | 3. Stair climbing |

| 4. Walking at 1.34 m·s−1 | 4. Washing dishes | 4. Walking at 1.56 m·s−1 | 4. Cycling (at V̇O2 21 ml·kg−1·min−1b) |

| 5. Walking at 1.79 m·s−1 | 5. Walking at 0.67 m·s−1 | 5. Weightsd | 5. Rowing (at V̇O2 21-25 ml·kg−1·min−1) |

| 6. Arm ergometer 25 Wc | 6. Arm ergometer (at V̇O2 8 ml·kg−1·min−1c) | 6. Cycling (at V̇O2 15 ml·kg−1·min−1b) | 6. Walking at 1.34 m·s−1 + 10% grade |

| 7. Running at 2.24 m·s−1 | 7. Loading/unloading boxesa | 7. Rowing (at V̇O2 15 ml·kg−1·min−1) | |

| 8. Ball toss game | 8. Simulated golf e | ||

| 9. Walking with stair climbing | |||

| 10. Basketball dribble f | |||

| 11. Arm ergometer (at V̇O2 15 ml·kg−1·min−1c) | |||

1.0 m·s−1 = 2.24 miles per hour; W, Watts; V̇O2, oxygen uptake

Participants moved items weighing a total of 5.4 kg from one box to another and then moved these boxes across two tables placed 2.1 m apart.

Cadence 60 – 70 rpm

Cadence 40 – 50 rpm

Bicep curls, shoulder abduction, squat, military press, shoulder flexion using 2.3 kg (women) and 4.5 kg (men) dumbbells.15 repetitions in 30 s; 30 s rest between exercises

1 full swing hitting an aerated golf ball followed by walking on a treadmill at 0.89 m·s−1 for 20 s followed by a chip, two putts and then walking on a treadmill at 0.89 m·s−1 for 20 s again

Participants alternated walking and dribbling the basketball for 30 s and bounce-passing the ball with the investigator for 30 s

For the structured routine, participants performed seven different activities for 8 min each with a 4-min seated rest period between each activity. There was a 10-min rest period prior to the start of the routine, which resulted in 90 min of data collection. The order of the activities was randomized for each participant except for running at 2.24 m·s−1, which was performed at the end to minimize any energy expenditure carry-over effects of this vigorous-intensity activity on the light- or moderate-intensity activities.

During the semi-structured routine, participants performed 12 different activities (4 sedentary/light-intensity, 4 moderate-intensity, and 4 vigorous-intensity) that were randomly selected from the list of activities shown in Table 2. This allowed us to assess the SenseWear over a wide range of activities that are performed by free-living individuals per guidelines of the larger National Institutes of Health study as described previously (Lee et al., 2014). Each activity was performed for 4 min 50 s, allowing for 10 s to transition to the next activity. The semi-structured routine was preceded by 5 min of seated rest. Due to initialization delay for the monitor, data during the first min of seated rest were not collected on all subjects. Therefore, only 4 min of seated rest were used for data analysis, resulting in 64 min of data collection in the semi-structured routine.

Indirect Calorimetry

Ventilation and pulmonary gas exchange were measured breath-by-breath with the Oxycon™ Mobile portable system (Carefusion Inc., San Diego, CA). Calibration was performed prior to each activity routine according to manufacturer's instructions. energy expenditure (kcal·min−1) was expressed as 1-min averages of breath-by-breath data. Test-retest reliability (using intraclass correlation coefficients, ICC) for indirect calorimetry was assessed in our laboratory for 24 participants that performed the structured routine on two separate occasions and was 0.98 for min-by-min energy expenditure and 0.91 for total energy expenditure (Bhammar, Sawyer, Tucker, Baez, & Gaesser, 2013, May). Using the same dataset, the coefficient of variation for the test retest reliability for total energy expenditure was estimated at 8.2% (95% CI: 6.2 – 12.2%). For data analysis of physical activity intensity classification, MET values were calculated by dividing measured V̇O2 (ml·kg−1·min−1) by 3.5 ml·kg−1·min−1, rather than the Compendium of Physical Activity (Ainsworth et al., 2011). The intensities of activities were defined on the basis of MET levels: 1 < MET ≤ 3 for sedentary/light-intensity; 3 < MET ≤ 6 for moderate-intensity; and MET > 6 for vigorous-intensity (Ainsworth et al., 2011).

SenseWear Armband

Participants were fitted with the SenseWear (Model MF-SW, Body Media, Pittsburgh, PA) over the left triceps brachii muscle, midway between the elbow and the shoulder, prior to starting both activity routines. Energy expenditure from the SenseWear was recorded in 1-min epochs. Data were processed using algorithm v2.2 (SenseWear 7.0) and v5.2 h (SenseWear 8.1). The currently available v5.2 h is an update from previous v5.2 e (SenseWear 8.0). The test-retest reliability (using ICC) for the SenseWear was 0.94 for min-by-min energy expenditure and 0.95 for total energy expenditure (Bhammar et al., 2013, May). Using the same dataset, the coefficient of variation for the test retest reliability for total energy expenditure was estimated at 6.3% (95% CI: 4.7 – 9.5%). All minute-by-minute energy expenditure data from the SenseWear and indirect calorimetry were plotted over time and were visually inspected to confirm time-alignment.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). All P-values were calculated assuming two-tailed hypothesis; P < 0.05 was considered significant. Effect size estimations were expressed using Cohen's d. Linear mixed models were used to detect differences between methods (i.e., indirect calorimetry, SenseWear v2.2, and v5.2) in total energy expenditure, minute-by-minute energy expenditure for different activities, and time spent in light-, moderate-, and vigorous-intensity physical activity. Method, sex, and method x sex were treated as fixed factors, and BMI and age were treated as random factors. In the minute-by-minute energy expenditure models, time was included as a random factor to account for repeated observations made in the same individual. If there was a significant main effect, post hoc analysis was conducted using Bonferroni comparisons.

Mean absolute percentage errors were calculated for individual activities to reflect true error in energy expenditure estimation. Differences in mean absolute percent error between SenseWear v2.2 and v5.2 were detected with paired t-tests. Additionally, we estimated the contribution of energy expenditure error for each physical activity to the total error in energy expenditure for both SenseWear v2.2 and v5.2. First, the difference in kcal·min−1 between indirect calorimetry and SenseWear was calculated by using data during min 4-7 of each physical activity performed in the structured routine and min 4-5 of each physical activity performed in the semi-structured routine. The resulting difference was multiplied by 8 for the structured routine since each activity was performed for 8 min, and by 5 for the semi-structured routine since each activity was performed for 5 min, to produce a total kcal difference between indirect calorimetry and SenseWear for each physical activity. The only exception was seated rest, which comprised 34 total min of the 90-min structured routine and 4 min of the semi-structured routine. This method was used because it allowed us to estimate steady-state error rather than minute-by-minute error, which could have been greater due to the time delay in attaining steady-state V̇O2 at the start and end of each activity (Gaesser & Brooks, 1984) that affects energy expenditure estimates by indirect calorimetry but not those by the SenseWear.

Bland-Altman plots were used to examine agreement in total energy expenditure between the three methods (Bland & Altman, 1986). Limits of agreement were established as 1.96 SD from the mean difference. Individual Pearson correlation coefficients were computed to evaluate overall measurement agreement using minute-by-minute energy expenditure data. The Fisher z transformation method was used when averaging individual correlation coefficients. Coefficients of variation for the typical error of estimate were calculated from the standard error of estimate of log transformed data (Hopkins, 2015). Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics version 21 (IBM, Armonk, NY).

Results

Structured Routine

Both SenseWear v2.2 and v5.2 overestimated total energy expenditure when compared with indirect calorimetry (Table 3). There was a significant method x sex interaction, where v2.2 significantly overestimated total energy expenditure as compared to v5.2 only in women (336.0 ± 51.0 kcal vs. 316.4 ± 39.4 kcal; Cohen's d = 0.44; P = 0.034), but not in men (419.3 ± 64.3 kcal vs. 427.8 ± 53.1 kcal; Cohen's d = 0.14; P = 1.000). Both SenseWear v2.2 and 5.2 signficantly overestimated energy expenditure when compared to indirect calorimetry for women (283.9 ± 51.5 kcal; Cohen's d = 1.01 and 0.71, respectively; P < 0.01) and men (342.9 ± 36.5 kcal; Cohen's d = 1.48 and 1.88, respectively; P < 0.01).

Table 3.

Total energy expenditure (EE) measured by indirect calorimetry and estimated by SenseWear Armbands v2.2 and v5.2 for both structured and semi-structured routines. Steady-state EE for individual activities for the structured routine and time spent in light (≤ 3 METs), moderate (3 – ≤ 6 METs), and vigorous (> 6 METs) physical activity based on MET levels for the semi-structured routine are also shown.

| Indirect Calorimetery | SenseWear Armband v2.2 | SenseWear Armband v5.2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | 95% CI | Mean ± SD | 95% CI | Cohen's d* | Mean ± SD | 95% CI | Cohen's d* | |

| Total EE (kcal) | ||||||||

| Structured Routine | 297.8 ± 54.2 | 278.9 – 316.7 | 355.6 ± 64.3a | 333.2 – 378.0 | 0.97 | 342.6 ± 63.8a | 320.3 – 364.9 | 0.76 |

| Semi-structured Routine | 262.8 ± 52.9 | 243.8 – 281.9 | 312.2 ± 74.5a | 285.4 – 339.1 | 0.76 | 275.2 ± 63.0b | 252.5 – 297.9 | 0.21 |

| Steady-State EE (kcal·min−1) | ||||||||

| Seated Rest | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 1.1 – 1.3 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 1.1 – 1.3 | 0.00 | 1.4 ± 0.3a, b | 1.3 – 1.5 | 0.67 |

| Load/Unload Boxes | 2.5 ± 0.8 | 2.2 – 2.7 | 3.8 ± 1.1a | 3.4 – 4.2 | 1.35 | 3.5 ± 1.3a,b | 3.1 – 3.9 | 0.93 |

| Sweeping | 2.6 ± 1.2 | 2.2 – 3.0 | 4.3 ± 1.6a | 3.7 – 4.8 | 1.20 | 3.4 ± 1.2a, b | 3.0 – 3.9 | 0.67 |

| Arm Ergometer at 25 W | 3.4 ± 0.9 | 3.1 – 3.7 | 4.1 ± 1.1a | 3.8 – 4.4 | 0.70 | 4.0 ± 1.2a | 3.6 – 4.4 | 0.57 |

| Cycle Ergometer at 50 W | 4.2 ± 0.6 | 4.0 – 4.3 | 4.3 ± 1.7 | 3.8 – 4.9 | 0.08 | 3.2 ± 1.5 | 2.8 – 3.7 | −0.88 |

| Walking 1.34 m·s−1 | 4.2 ± 1.0 | 3.9 – 4.6 | 5.4 ± 1.6a | 4.9 – 6.0 | 0.90 | 4.9 ± 1.3a, b | 4.4 – 5.3 | 0.60 |

| Walking 1.79 m·s−1 | 6.0 ± 1.5 | 5.4 – 6.5 | 7.0 ± 1.8a | 6.4 – 7.6 | 0.60 | 6.5 ± 1.6a,b | 6.0 – 7.1 | 0.32 |

| Running 2.24 m·s−1 | 9.4 ± 2.1 | 8.6 – 10.1 | 10.5 ± 2.1a | 9.7 – 11.2 | 0.52 | 11.1 ± 1.9a,b | 10.5 – 11.8 | 0.85 |

| Time (minutes)** | ||||||||

| Sedentary/Light | 32 ± 8 | 30 – 35 | 16 ± 6a | 14 – 18 | 2.26 | 23 ± 8a,b | 20 – 26 | 1.13 |

| Moderate | 26 ± 6 | 24 – 28 | 42 ± 6a | 40 – 44 | 2.67 | 37 ± 7a,b | 34 – 39 | 1.69 |

| Vigorous | 7 ± 5 | 5 – 9 | 7 ± 6 | 5 – 9 | 0.00 | 6 ± 5 | 4 – 7 | 0.20 |

SD, standard deviation; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval; MET, metabolic equivalent; 1.0 m·s−1 = 2.24 miles per hour; W, Watts.

Significantly different from indirect calorimetry (P < 0.05)

Significantly different from Senwear Armand v2.2 (P < 0.05)

Effect sizes are represented by Cohen's d and are in comparison with indirect calorimetry

Represents time spent in sedentary/light, moderate, and vigorous activity during the semi-structured routine.

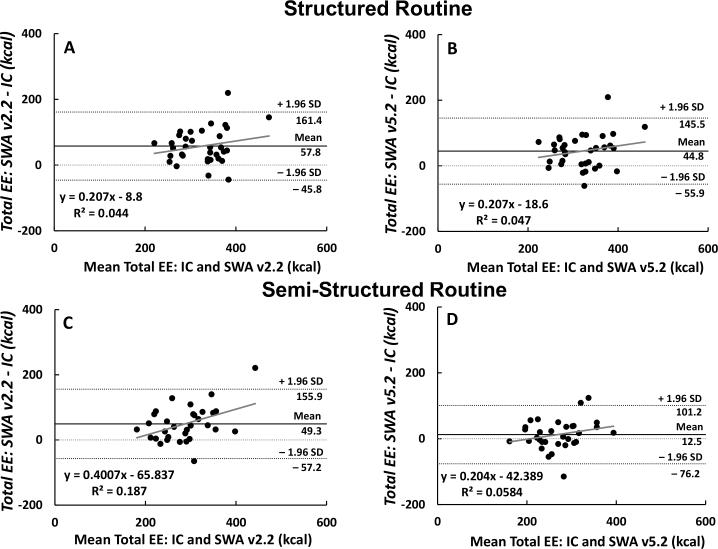

For both SenseWear v2.2 and v5.2, Bland-Altman analysis showed similar limits of agreement and no proportional bias (Figures 1A and 1B). The individual correlation coefficients for the entire 90-min protocol between indirect calorimetry and SenseWear ranged from 0.76 to 0.95 for v2.2 (mean = 0.89) and from 0.76 to 0.96 for v5.2 (mean = 0.89). The coefficients of variation for total energy expenditure for both Sensewear v2.2 and v5.2 were the same (15.4%; 95% CI: 12.2 – 20.9%) when compared with indirect calorimetry.

Figure 1.

Bland-Altman plots for total energy expenditure (EE) during the structured routine for Sensewear Armband (SWA) v2.2 (Panel A) and v5.2 (Panel B) and during the semi-structured routines for SWA v2.2 (Panel C) and v5.2 (Panel D).

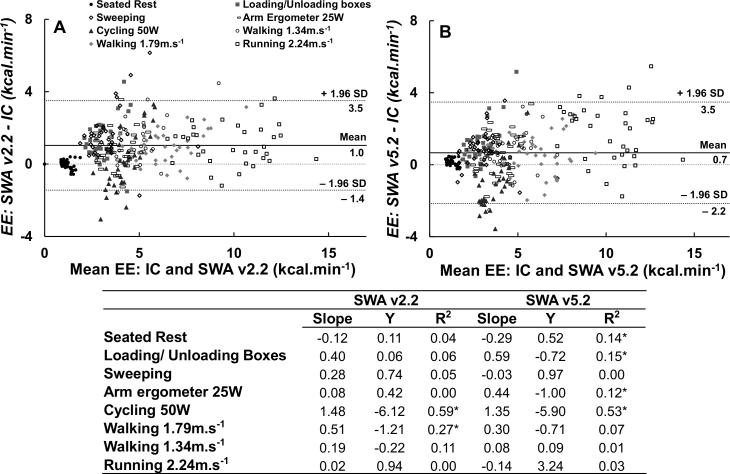

Both SenseWear v2.2 and v5.2 significantly overestimated steady-state energy expenditure during all activities except cycle ergometry (Table 3). SenseWear v5.2 also overestimated resting energy expenditure. Bland-Altman analysis for steady-state energy expenditure showed that the limits of agreement (± 1.96 SD) for SenseWear v5.2 were similar to v2.2 (Figures 2A and 1B). Although mean energy expenditure for cycle ergometry was not different between indirect calorimetry and SenseWear (Table 3), both v2.2 and v5.2 showed a moderate proportional bias (i.e. R2 between 0.4 and 0.6 (Christine & John, 2002) for energy expenditure during this activity, with underestimation at low energy expenditure and overestimation at high energy expenditure levels (Figure 2A and B).

Figure 2.

Bland-Altman plots for steady-state energy expenditure (EE) during individual activities during the structured routine for Sensewear Armband (SWA) v2.2 (A) and v5.2 (B). The table represents slope, Y intercept, and R2 for individual activities in the routine. * Significant correlation P < 0.05.

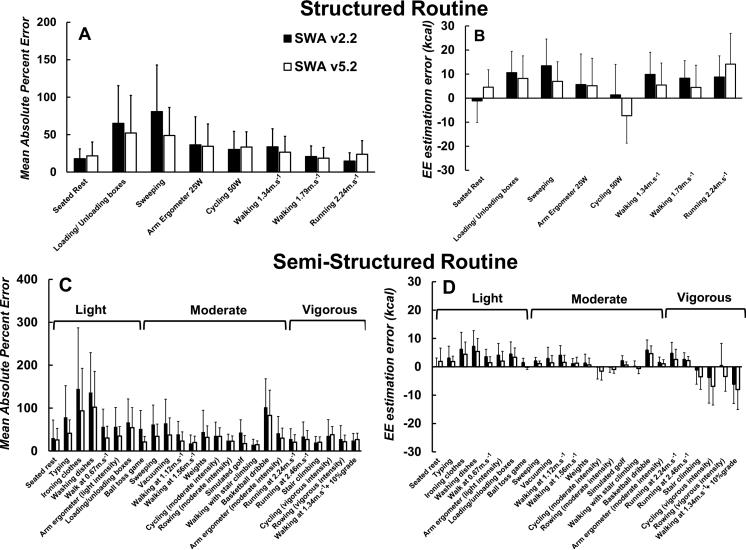

The mean absolute percent errors for both SenseWear v2.2 and v5.2 were highest for light-intensity activities like loading/unloading boxes and sweeping (Figure 3A). For moderate- and vigorous-intensity activities, mean absolute percent errors for SenseWear v2.2 and v5.2 were similar, and generally between 15-35%. Overall, the average mean absolute percent error was lower for the SenseWear v5.2 (32 ± 30%; 95% CI: 28 – 36%) compared with the v2.2 (37 ± 40%; 95% CI: 32 – 42%; Cohen's d = 0.14; P = 0.005). For SenseWear v5.2, approximately 30% (13.6 kcal) of the energy expenditure estimation error over the 90-min routine (44.8 kcal; Table 3) was attributable to running at 2.24m·s−1 (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Mean absolute percentage error and relative contribution of individual activities to overall EE estimation error for Sensewear Armband (SWA) v2.2 and v5.2 for different activities in the structured (Panels A and B) and semi-structured routines (Panel C and D).

Semi-structured routine

SenseWear v5.2 total energy expenditure estimate was not different from indirect calorimetry (P = 0.35), whereas v2.2 significantly overestimated total energy expenditure (P < 0.001; Table 3). There was a significant method x sex interaction, where v2.2 significantly overestimated total energy expenditure as compared to v5.2 only in women (290.4 ± 56.0 kcal vs. 250.4 ± 42.1 kcal; P < 0.001), but not in men (390.3 ± 83.8 kcal vs. 363.9 ± 41.0 kcal P = 0.875). Only SenseWear v2.2 signficantly overestimated energy expenditure when compared to indirect calorimetry for women (249.4 ± 48.0 kcal; P < 0.001) and men (310.7 ± 42.9 kcal; P = 0.017).

Bland-Altman analysis for total energy expenditure showed narrower limits of agreement for v5.2 compared with v2.2. SenseWear v2.2 also showed a weak proportional bias (P = 0.014) (Figures 1C and 1D). The individual correlation coefficients for the entire 64-min protocol between indirect calorimetry and SenseWear ranged from 0.23 to 0.87 for v2.2 (mean = 0.66) and from 0.41 to 0.90 for v5.2 (mean = 0.73). The coefficient of variation for total energy expenditure was 15.8% (95% CI: 12.4 – 21.6%) for Sensewear v2.2 and 16.2% (95% CI: 12.8 – 22.3%) for v5.2 when compared with indirect calorimetry.

Mean absolute percent errors were higher for light-intensity activities, and lower for the moderate- and vigorous-intensity activities for both SenseWear v2.2 and v5.2, with mean absolute percent errors generally lower for SenseWear v5.2 (39 ± 18%; 95% CI: 35 – 42%) than v2.2 (51 ± 26%; 95% CI: 47 – 56%; Cohen's d = 0.54; P < 0.001; Figure 3C). The closer agreement with indirect calorimetry for total energy expenditure during the semi-structured routine for SenseWear v5.2 compared with v2.2 (Table 3) is illustrated in Figure 3D, which shows that, for most activities, v5.2 produced slightly smaller positive errors, and larger negative errors than v2.2.

Both SenseWear v2.2 and v5.2 overestimated time spent in moderate-intensity activity and underestimated time spent in light-intensity activity when compared with indirect calorimetry (Table 3). In addition, SenseWear v5.2 provided significantly better estimates of time spent in sedentary/light- or moderate-intensity activity when compared with v2.2 (Table 3). Both algorithms accurately estimated time spent in vigorous-intensity activity (main effect P = 0.625). There was no method x sex interaction for time spent in light-, moderate-, or vigorous-intensity physical activity.

Discussion

Both SenseWear v2.2 and v5.2 overestimated energy expenditure during the structured routine when compared with indirect calorimetry. In contrast, during the semi-structured routine, SenseWear v5.2 provided an estimate of total energy expenditure not different than that of indirect calorimetry. This is because v5.2 generally produced smaller errors in energy expenditure estimation for activities in which both algorithms overestimated energy expenditure (mostly light-to-moderate-intensity physical activity), and larger errors in energy expenditure estimation for activities in which both algorithms underestimated energy expenditure (e.g., cycling, rowing, stair climbing, and walking up a grade) (Figure 2D). This underscores the importance of physical activity selection when assessing whether the SenseWear provides a good estimate of energy expenditure during the performance of a particular physical activity routine involving multiple activities. This also has implications for individuals that engage in one specific exercise and are using the SenseWear for estimating energy expenditure in free-living conditions, where the estimate of total energy expenditure could be over- or under-estimated depending on physical activity selection. The improved performance of v5.2 could also be due to the fact that most of our subjects (26 of 34) were women. We observed a significant method x sex interaction, with v5.2 producing energy expenditure estimates closer to the indirect calorimetry values in women compared to men.

We are aware of only three published reports that compared the newest algorithm v5.2 with previous v2.2 for estimating energy expenditure during physical activity (Lee et al., 2014; Smith et al., 2012; Van Hoye et al., 2014). Van Hoye et al (Van Hoye et al., 2014) reported that SenseWear v5.2 did not improve energy expenditure estimation in young men and women while standing, walking, or running on a treadmill during indoor temperatures of 19° C and 26° C, but did improve energy expenditure estimation while walking and running at 33° C. Smith et al (Smith et al., 2012) studied pregnant women while they performed seven different activities (typing, folding laundry, sweeping, walking at 0.89, 1.12, and 1.34 m·s−1 and walking at 1.34 m·s−1 up a 3% incline). This is comparable to our structured routine, albeit with a narrower range of indirect calorimetry-measured energy expenditure (≈1-5 kcal·min−1 vs. ≈1-9 kcal·min−1). With the exception of typing, incline walking, and walking at.89 m·s−1 (SenseWear v5.2 only), both algorithms overestimated energy expenditure. Our results are consistent with these findings in that both SenseWear v2.2 and v5.2 overestimated energy expenditure for all activities in our structured routine except for cycle ergometry, with generally lower mean absolute percent errors for SenseWear v5.2 than v2.2. Smith et al (Smith et al., 2012) also showed consistently lower mean absolute percent errors for SenseWear v5.2 for all activities except walking at 1.34 m·s−1 with 0% incline.

Our results for the semi-structured routine are similar to those reported for children ages 7 to 13 yr, who performed a physical activity routine consisting of 12 activities of varying intensity, for 5 min each with a 1-min rest between each activity (Lee et al., 2014). For both adults and children, the newest algorithm produced smaller mean absolute percent error in estimated energy expenditure than the previous algorithm. Thus SenseWear v5.2 may offer an advantage over SenseWear v2.2 for estimating total energy expenditure during physical activity provided that the routine includes a variety of light-, moderate-, and vigorous-intensity activities that counterbalance each other in overestimating and underestimating energy expenditure. It should be noted that the subject population in Lee et al. was also predominantly girls (34 of 45). If the method x sex interaction we found is present in children, the improved results of v5.2 in children could partly be attributable to the high percentage of girls in that study.

It may also be useful to know the accuracy of the device for estimating energy expenditure for specific activities. Based on the steady-state data from the structured physical activity routine, SenseWear v5.2 significantly improved energy expenditure estimation for sweeping, loading/unloading boxes, and walking on a level grade, but performed worse than v2.2 for seated rest (Table 3). Physical activity that involved upper body movements (e.g., sweeping, washing dishes, ironing, typing) tended to produce greater energy expenditure overestimation due to increased accelerometer output from the SenseWear. This was seen across both algorithms and is consistent with previously published studies (Lee et al., 2014; Smith et al., 2012).

Although the mean absolute percent error results suggest that SenseWear v5.2 is an improvement over v2.2, it is also useful to interpret the results from the perspective of actual energy expenditure estimation error. In the structured routine, for example, the mean absolute percent errors for cycling and for walking at 1.34 and 1.79 m·s−1 were similar for both SenseWear v5.2 and v2.2 (Figure 2A). However, the contribution to the energy expenditure estimation error (kcal) differed markedly (Figure 3B). Also, due to the high absolute energy expenditure for running at 2.24 m·s−1 (Table 3), the energy expenditure estimation error by SenseWear v5.2 for this activity was much higher than any of the other activities despite having a relatively low mean absolute percent error (Figure 2A). In fact, the energy expenditure estimation error for 8 min of running at 2.24 m·s−1 (13.6 kcal) represented 30% of the total difference in energy expenditure (44.8 kcal) between SenseWear v5.2 and indirect calorimetry (Table 3) during the structured routine. These results also have important implications for runners who use the SenseWear to track energy expenditure, where the SenseWear may overestimate energy expenditure by approximately 100 kcal for every hour of running. Conversely, for cyclists, v5.2 underestimates energy expenditure by approximately 83 kcal for every hour of vigorous cycling. The energy expenditure estimation error for cycling was considerably lower in v2.2. Our results indicate a need for activity-specific algorithms for activities such as cycling and running at different intensities. This would improve confidence in total energy expenditure estimates over longer periods for a majority of healthy adults.

For running energy expenditure, Drenowatz and Eisenmann (Drenowatz & Eisenmann, 2011) have suggested that the SenseWear may experience a ceiling effect, where it tends to underestimate energy expenditure for activities that are below 10 METs. Since the running speeds used in this study were below 10 METs on average, this could explain why the present study showed overestimation of energy expenditure and METs during running, consistent with previous reports (Drenowatz & Eisenmann, 2011; King et al., 2004). Also consistent with this hypothesis, two studies, Dudley et al and Van Hoye et al showed that SenseWear underestimated METs during running for average speeds of 2.7 m.s−1, which would be greater than 10 METs (Dudley, Bassett, John, & Crouter, 2012; Van Hoye et al., 2014).

An unexpected result for SenseWear v5.2 was the significant overestimation of energy expenditure during seated rest (Table 3). The ~0.2 kcal·min−1 overestimation during seated rest may be of little consequence for energy expenditure during physical activity routines lasting ~60-90 min, as in the present study. However, the ~17% error could contribute significantly to total energy expenditure estimation during the course of a day, especially considering that only 19% of the total energy expenditure is accounted for by physical activity in a field setting in healthy adults (Plasqui, Joosen, Kester, Goris, & Westerterp, 2005). Future versions of the SenseWear algorithms may consider reverting to the more accurate v2.2 equations for resting energy expenditure.

Both SenseWear v2.2 and v5.2 resulted in significant misclassification of physical activity intensity, generally underestimating time spent in light-intensity activity and overestimating time spent in moderate-intensity activity. This is attributable to the consistent and significant overestimation of energy expenditure for activities such as sweeping and loading/unloading boxes that are in the range of 2.0-2.5 METs (Table 3). These results have implications for using the SenseWear when assessing whether physical activity guidelines are being met, as time spent in moderate-intensity activity during the semi-structured routine was overestimated by 42% (v5.2) and 62% (v2.2). It should be noted that we did not use measured values of resting energy expenditure to calculate METs from indirect calorimetry, and since measured resting energy expenditure may yield a MET value closer to 2.6 ml.min−1.kg−1 (Byrne, Hills, Hunter, Weinsier, & Schutz, 2005), we have likely underestimated the true MET value of activities in the routine and this could have affected the true intensity classification for our participants.

Our study has several strengths. Subjects performed both structured and semi-structured physical activity routines that included a variety of light-, moderate-, and vigorous-intensity activities that utilized both lower- and upper-body movements. We also performed multiple analyses that included both steady-state and non-steady-state data. The structured routine allowed for energy expenditure estimation for each activity while performed during steady-state conditions. The semi-structured routine, without rest periods between activities, allowed for inclusion of non-steady-state transitions between activities that might better reflect “free-living” conditions. Lastly, the inclusion of energy expenditure estimation errors in absolute terms (kcal) for each activity provided an additional perspective that is not readily apparent from looking at mean absolute percent error results alone.

This study also has limitations. Although we used a wide variety of activities, both routines were relatively short and performed in a controlled laboratory environment. The sample size was somewhat small, although similar to that of other recent comparisons of SenseWear v5.2 and v2.2 (Smith et al., 2012; Van Hoye et al., 2014). Our sample was also unbalanced (i.e., fewer men than women) and contained predominantly young healthy adults, which could limit the generalizability of this study. Future research should focus on validating the new algorithm in chronic disease populations and over longer periods in free-living conditions. Since two of the three previously published studies comparing v2.2 and v5.2 used predominantly (Lee et al., 2014) or exclusively (Smith et al. 2012) females, additional research is necessary to examine whether the method x sex interaction we observed can be confirmed with larger studies containing a balanced enrollment of sexes. Finally, we did not examine baseline activity levels of these participants, and their activity status (sedentary vs. active) may have affected the results.

In conclusion, the SenseWear v5.2 generally offers better estimates of energy expenditure and physical activity levels when compared with its predecessor, v2.2, but still overestimates energy expenditure for most activities. Because v5.2 reduced estimation error for most activities that SenseWear overestimates energy expenditure, but also increased estimation error for activities that SenseWear underestimates energy expenditure, performance of the SenseWear v5.2 relative to indirect calorimetry will depend on the mix of activities included in physical activity routines. Since the SenseWear Armband is comparable to other commercially available activity monitors for estimating energy expenditure and physical activity levels in healthy adults (Van Remoortel et al., 2012), it is a viable option for researchers, clinicians, and individuals interested in comprehensive monitoring of physical activity in healthy adults.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank volunteers of the study for their participation.

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01 HL091006.

Footnotes

This research was conducted at the Healthy Lifestyles Research Center at Arizona State University.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Herrmann SD, Meckes N, Bassett DR, Tudor-Locke C, Leon AS. 2011 compendium of physical activities: a second update of codes and MET values. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2011;43(8):1575–1581. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31821ece12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benito P, Neiva C, Gonzalez-Quijano P, Cupeiro R, Morencos E, Peinado A. Validation of the SenseWear armband in circuit resistance training with different loads. European Journal of Applied Physiology. 2012;112(8):3155–3159. doi: 10.1007/s00421-011-2269-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berntsen S, Hageberg R, Aandstad A, Mowinckel P, Anderssen SA, Carlsen KH, Andersen LB. Validity of physical activity monitors in adults participating in free-living activities. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2010;44(9):657–664. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2008.048868. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2008.048868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhammar DM, Sawyer BJ, Tucker WJ, Baez JC, Gaesser GA. Actiheart and Actigraph in Adults Poster session presented at the meeting of the American College of Sports Medicine. Indianapolis, IN.: May, 2013. Physical Activity and Energy Expenditure Measurements Using Sensewear Armband. [Google Scholar]

- Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical-Methods for Assessing Agreement between 2 Methods of Clinical Measurement. Lancet. 1986;1(8476) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brazeau AS, Karelis AD, Mignault D, Lacroix MJ, Prud'homme D, Rabasa-Lhoret R. Accuracy of the SenseWear Armband (TM) during Ergocycling. International Journal of Sports Medicine. 2011;32(10):761–764. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1279768. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1279768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne NM, Hills AP, Hunter GR, Weinsier RL, Schutz Y. Metabolic equivalent: one size does not fit all. Journal of Applied Physiology (Bethesda, MD: 1985) 2005;99(3):1112–1119. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00023.2004. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00023.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm D, Collis M, Kulak L, Davenport W, Gruber N. Physical Activity Readiness. British Columbia Medical Journal. 1975;17:375–378. [Google Scholar]

- Christine DP, John R. Statistics Without Maths for Psychology Using SPSS for Windows. Prentice Hall, Pearson Education; Harlow, England: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Drenowatz C, Eisenmann JC. Validation of the SenseWear Armband at high intensity exercise. European Journal of Applied Physiology. 2011;111(5):883–887. doi: 10.1007/s00421-010-1695-0. doi: 10.1007/s00421-010- 1695-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudley P, Bassett D, John D, Crouter S. Validity of a Multi-Sensor Armband for Estimating Energy Expenditure during Eighteen Different Activities. Journal of Obesity and Weight Loss Therapy. 2012;2(146):1–7. doi: 10.4172/2165-7904.1000146. doi: 10.4172/2165-7904.1000146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdogan A, Cetin C, Karatosun H, Baydar ML. Accuracy of the Polar S810iTM Heart Rate Monitor and the Sensewear Pro ArmbandTM to Estimate Energy Expenditure of Indoor Rowing Exercise in Overweight and Obese Individuals. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport. 2010;9:508–516. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fruin ML, Rankin JW. Validity of a multi-sensor armband in estimating rest and exercise energy expenditure. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2004;36(6):1063–1069. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000128144.91337.38. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000128144.91337.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaesser GA, Brooks GA. Metabolic bases of excess post-exercise oxygen consumption: A review. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 1984;16(1):29–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins WG. Spreadsheets for analysis of validity and reliability. Sportscience. 2015;19:36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Jakicic JM, Clark K, Coleman E, Donnelly JE, Foreyt J, Melanson E, Volpe SL. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Appropriate intervention strategies for weight loss and prevention of weight regain for adults. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2001;33(12):2145–2156. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200112000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King GA, Torres N, Potter C, Brooks TJ, Coleman KJ. Comparison of activity monitors to estimate energy cost of treadmill exercise. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2004;36(7):1244–1251. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000132379.09364.f8. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000132379.09364.F8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J-M, Kim Y, Bai Y, Gaesser GA, Welk GJ. Validation of the SenseWear Mini Armband in Children during Semi-Structure Activity Settings. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2014.10.004. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2014.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papazoglou D, Augello G, Tagliaferri M, Savia G, Marzullo P, Maltezos E, Liuzzi A. Evaluation of a multisensor armband in estimating energy expenditure in obese individuals. Obesity. 2006;14(12):2217–2223. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.260. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plasqui G, Joosen AMCP, Kester AD, Goris AHC, Westerterp KR. Measuring free-living energy expenditure and physical activity with triaxial accelerometry. Obesity Research. 2005;13(8):1363–1369. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal KR, Gutin B. Thermic effects of food and exercise in lean and obese women. Metabolism: Clinical & Experimental. 1983;32(6):581–589. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(83)90028-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal KR, Gutin B, Nyman AM, Pi-Sunyer FX. Thermic effect of food at rest, during exercise, and after exercise in lean and obese men of similar body weight. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1985;76(3):1107–1112. doi: 10.1172/JCI112065. doi: 10.1172/jci112065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KM, Lanningham-Foster LM, Welk GJ, Campbell CG. Validity of the SenseWear® Armband to Predict Energy Expenditure in Pregnant Women. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2012;44(10):2001–2008. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31825ce76f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Hoye K, Boen F, Lefevre J. Validation of the SenseWear Armband in different ambient temperatures. Journal of Sports Sciences. 2014:1–12. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2014.981846. (ahead-of-print) doi:10.1080/02640414.2014.981846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Remoortel H, Giavedoni S, Raste Y, Burtin C, Louvaris Z, Gimeno-Santos E, Damijen E. Validity of activity monitors in health and chronic disease: a systematic review. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2012;9 doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-9-84. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-9-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warburton DE, Nicol CW, Bredin SS. Health benefits of physical activity: the evidence. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2006;174(6):801–809. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.051351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welk GJ. Principles of design and analyses for the calibration of accelerometry-based activity monitors. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2005;37(11):S501. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000185660.38335.de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welk GJ, McClain JJ, Eisenmann JC, Wickel EE. Field validation of the MTI Actigraph and BodyMedia armband monitor using the IDEEA monitor. Obesity. 2007;15(4):918–928. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.624. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wing RR, Phelan S. Long-term weight loss maintenance. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2005;82(1):222S–225S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/82.1.222S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]