Abstract

Summary

Persistence with osteoporosis therapy remains low and identification of factors associated with better persistence is essential in preventing osteoporosis and fractures. In this study, patient understanding of dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) results and beliefs in effects of treatment were associated with treatment initiation and persistence.

Introduction

The purpose of this study is to examine patient understanding of their DXA results and evaluate factors associated with initiation of and persistence with prescribed medication in first-time users of anti-osteoporotic agents. Self-reported DXA results reflect patient understanding of diagnosis and may influence acceptance of osteoporosis therapy. To improve patient understanding of DXA results, we provided written information to patients and their referring general practitioner (GP), and evaluated factors associated with osteoporosis treatment initiation and 1-year persistence.

Methods

Information on diagnosis was mailed to 1,000 consecutive patients and their GPs after DXA testing. One year after, a questionnaire was mailed to all patients to evaluate self-report of DXA results, drug initiation and 1-year persistence. Quadratic weighted kappa was used to estimate agreement between self-report and actual DXA results. Multivariable logistic regression was used to evaluate predictors of understanding of diagnosis, and correlates of treatment initiation and persistence.

Results

A total of 717 patients responded (72%). Overall, only 4% were unaware of DXA results. Agreement between self-reported and actual DXA results was very good (κ=0.83); younger age and glucocorticoid use were associated with better understanding. Correctly reported DXA results was associated with treatment initiation (OR 4.3, 95% CI 1.2–15.1, p=0.02), and greater beliefs in drug treatment benefits were associated with treatment initiation (OR 1.4, 95%CI 1.1–1.9, p=0.006) and persistence with therapy (OR 1.8, 95% CI 1.2–2.7, p=0.006).

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that written information provides over 80% of patients with a basic understanding of their DXA results. Communicating results in writing may improve patient understanding thereby also improve osteoporosis management and prevention.

Keywords: Bone density, Communication, DXA scanning, Osteoporosis, Self-report

Introduction

Therapeutic interventions to prevent osteoporosis-related fractures require long-term therapy. Unfortunately, adherence with osteoporosis pharmacotherapy is a continuing challenge [1–4], and failure to adhere to treatment recommendations increases the risk of fragility fracture [5]. The extent of non-persistence varies, but in a meta-analysis of studies, assessing database-derived persistence rates in users of bishosphonates, as few as 46% (95% CI 38–55) persisted with treatment beyond 12 months [6]. Reasons for low persistence are multifactorial and include out-of-pocket costs of medication, difficulties with treatment regimen, side effects, and the asymptomatic nature of osteoporosis [7, 8]. The relative importance of these factors may vary across countries and healthcare programs.

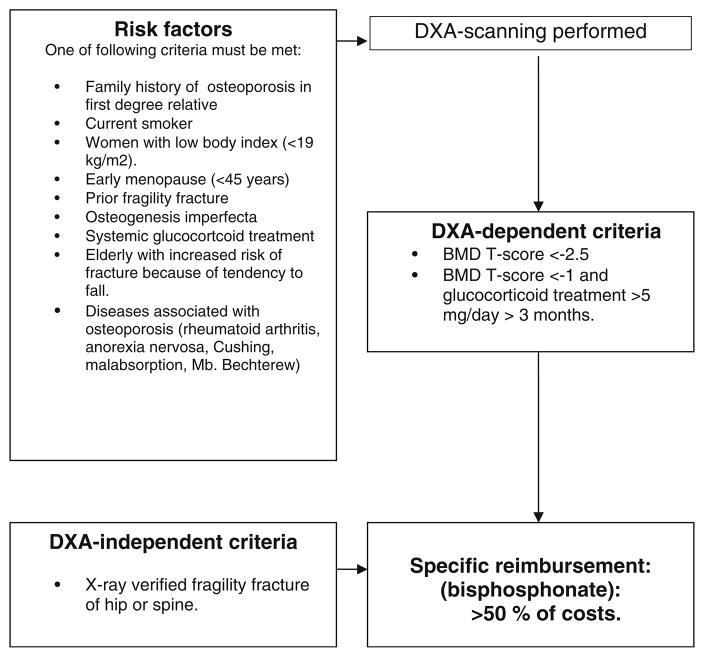

Denmark has national health (Danish National Board of Health) and pharmacy (Danish Medical Agency) benefit programs [9]. These programs include access to primary care medical services free of charge and partial coverage for prescription drugs listed in the National formulary. Dual x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) is also covered upon physician referral according to National reimbursement guidelines (Fig. 1). Therapeutic options for treating osteoporosis in Denmark include bisphosphonates, raloxifene, strontium ranelate, and parathyroid hormone (PTH) agents. However, specific criteria are required to receive reimbursement by The Danish Medicines Agency: (1) prior fragility fracture, (2) bone mineral density (BMD) T-score ≤2.5, or (3) T-score ≤1 and long-term glucocorticoid treatment. Those meeting these criteria pay less than half of their prescription costs and reimbursement is automatically calculated at the pharmacy regardless of personal income. The citizens do not pay any special contributions to this scheme as it is financed through taxes. Since access to DXA examination is free and osteoporosis medication is affordable, these parameters cannot be considered modifiable barriers to diagnostics and treatment. Therefore, within the context of care in Denmark, the most important barriers to successful treatment of those identified with osteoporosis and recommended pharmacotherapy, are problems with adherence (compliance and persistence).

Fig. 1.

Guiding criteria for DXA-examination and rules of specific reimbursement according to the Danish National Board of Health and the Danish Medicines Agency

In spite of universal healthcare, osteoporosis is markedly underdiagnosed and undertreated in Denmark [10]. Other countries with similar healthcare systems, such as Canada [11] and Germany [12] report similar problems. Although a number of studies have identified patient persistence with pharmacotherapy as a major problem in osteoporosis management [6], few studies have aimed at identifying predictors of non-persistence or causes of treatment cessation [13], particularly in considering possible modifiable factors such as patient beliefs about osteoporosis treatment benefits and understanding of results of DXA results.

Self-report of DXA results reflect the patients’ understanding of information provided to them from the clinic and any modifying influence provided by their subsequent consultation with their general practitioner (family doctor, GP). Regrettably, prior studies have showed at best only moderate agreement between self-reported and actual DXA results [14, 15]. This is unfortunate for two reasons. First, failure to successfully convey an abnormal test result could lead the patient to failing to initiate and/or adhere to treatment and therefore place the patient at increased risk of fracture. Second, failure to successfully convey a normal test result can lead to false impression of illness and potentially impact on quality of life. However, clear strategies aimed at improving accurate knowledge transfer of DXA results between practitioner and patient remains to be defined [16].

We therefore set out to improve patient understanding of DXA results by providing standardized written information about diagnosis and treatment recommendations to patients and referring GPs. We then compared DXA results at baseline to self-report of results 1 year after (questionnaire), and also examined factors associated with treatment initiation and 1-year persistence. We hypothesized that patient self-report of DXA results would be good, and as previously identified [17] would correlate with treatment initiation. We also hypothesized that higher perceived benefits of osteoporosis pharmacotherapy would be associated with treatment initiation and persistence with therapy.

Methods

Patients

We identified 1,000 consecutive patients (men and women) referred for osteoporosis screening to a newly established publicly funded Danish osteoporosis clinic in the period 1 January 2005 to 28 March 2006. Patients had been referred for DXA scanning by their GP according to local guidelines [18]. All referrals were reviewed by an endocrinologist to assure the necessity of DXA examination, and all patients met the defined referral criteria. No patients were excluded from the initial identification process. Information on risk factors, medical history, alcohol consumption, and smoking history were obtained from the patient by the technologist in the form of a self-administered questionnaire at the time of DXA exam. Scanning was performed using the same dual energy X-ray absorptiometry machine (Hologic Discovery A). An osteoporosis specialist (endocrinologists: BA, PE) reviewed the DXA results and risk factor profile, entered these data into a database (approved by the data protection agency) and diagnosed patients based on lowest T-score of the femoral neck and the anterior posterior lumbar spine, and presence of low-energy fractures as: (1) osteoporosis [19] (T-score ≤2.5 and/or one or more low-energy fractures regardless of T-score), (2) osteopenia (T-scores between −2.5 and −1 SD), or (3) normal (T-score values above −1 SD).

Information letters

Standardized information letters (see Appendix) were mailed to patients and identical information was communicated electronically to referring GP shortly after DXA examination. Patients did not receive any verbal information or treatment advice. The letters included diagnosis based on DXA results, as well as individual treatment and lifestyle recommendations. The personalized information related to their reported risk factor profile. For example, information about the importance of smoking cessation was given to smokers only, and information on avoiding lifting heavy burdens only to patients with osteoporosis. All patients were encouraged to discuss the results with their GP, and those with osteoporosis were specifically encouraged to talk with their GP in order to initiate recommended treatment. The process did not involve any personal contact between the patient and the osteoporosis specialist.

Questionnaire

One thousand patients surviving to 1 year past their DXA exam were mailed a questionnaire and a self-addressed return envelope. Patients who were examined for the first time (88.4%) as well as patients who had more than one DXA (11.5%) were included. The questionnaire included multiple-choice questions about DXA test results (osteoporosis, osteopenia, or normal), health status, follow-up with referring physicians, current and past osteoporosis treatment, and among those reporting to have stopped pharmacotherapy, reasons for discontinuation. The questionnaire also included a Danish translation of a multi-item scale designed to measure patient perception regarding osteoporosis pharmacotherapy [20]. Replies were accepted only in writing and reminders were not used.

Outcome

We defined anti-osteoporotic drug initiation in this study as the reported use of one or more doses of any oral anti-osteoporotic drugs including bisphosphonates (alendronate, etidronate, ibandronate, risedronate), raloxifene, strontium ranelate, or PTH agents by a patient who had been recommended treatment initiation by the osteoporosis specialist. Persistence was defined by patients reporting to be taking their medication at the time of follow-up irrespective of interruptions in treatment.

Covariates

Patient demographics (age, gender) and risk factors (current smoking, current glucocorticoid treatment, family history in first-degree relative, and prior fragility fracture) were determined by self-report at the time of DXA examination. Information on correctly reported DXA results by self-report, and beliefs about osteoporosis treatment and self-reported health status were obtained by follow-up questionnaire 1 year after DXA examination. Confirmatory factor analysis supported the five-item osteoporosis drug treatment benefits scale structure as previously published [20] when completed among the full sample of respondents. However, when restricted to the subgroup with osteoporosis, confirmatory factor analysis suggested that splitting the five-item treatment benefits domain into one three-item scale measuring perceptions about drug benefits, and two individual items that examine whether a patient would consider treatment was a better fit. We therefore examined patient perceptions about drug benefits as a three-item scale, quantified as Z-scores. The three items that comprise the scale, translated from Danish into English were: (1) medications can build strong bones, (2) I would feel good about taking medications against osteoporosis, and (3) medical treatments can reduce the risk of broken bones. As confirmed by scale structure in our analysis, we also included two individual items that examine potential barriers to pharmacotherapy. These were measured based on agreement (agree or strongly agree) with the individual items.

Statistical analysis

Relationships between categorical variables and respondents/non-respondents were assessed using chi-squared or t test statistics. Descriptive statistics were used to compare risk factor prevalence. We used quadratic-weighted kappa statistics (values below 0.61 indicate from no to fair agreement, between 0.61 and 0.80 indicate good agreement, between 0.81 and 0.92 indicate very good agreement, and between 0.93 and 1.00 indicate excellent agreement) [21] to assess the agreement between self-reports of diagnosis and actual DXA results, each categorized as osteoporosis, osteopenia, or normal. Correlates of correct self-report of DXA results, osteoporosis treatment initiation, and persistence were evaluated by multivariable logistic regression. Given small sample sizes when studying correlates of treatment initiation and persistence, we restricted adjusted analyses of these outcomes to include covariates with p value <0.2 in unadjusted logistic results.

Results

Characteristics of the total study sample

Of 1,000 patients who had DXA scans performed and survived to 1 year, 717 responded to the questionnaire (Table 1). Respondents were similar to non-respondents in age, sex, and diagnosis. However, non-respondents were more likely to be smokers (32.8% vs. 24.4%, p= 0.007) and less likely to have a family history of osteoporosis (31.1% vs. 40.7%, p=0.005). Also, more non-respondents received glucocorticoid treatment though this difference was not statistically significant (12.3% vs. 16.6%, p=0.07).

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of the total study sample

| Total n=1,000 | Respondents n=717 | Non-respondents n=283 | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age | 63.5 (SD=10.3) | 62.6 (SD=10.8) | 0.9 |

| Female | 652 (91.0%) | 257 (91.0%) | 1.0 |

| DXA results | |||

| Osteoporosis | 217 (30.3%) | 71 (25.1%) | 0.18 |

| Osteopenia | 298 (41.6%) | 134 (47.4%) | |

| Normal | 202 (28.2%) | 78 (27.6%) | |

| Early menopause (age <45) | 95 (13.2%) | 36 (12.7%) | 0.82 |

| Smoking (current) | 175 (24.4%) | 93 (32.8%) | 0.007 |

| Glucocorticoid treatment (current) | 88 (12.3%) | 47 (16.6%) | 0.07 |

| Family history in first degree relative | 292 (40.7%) | 88 (31.1%) | 0.005 |

| Prior fragility fracture | 219 (30.5%) | 72 (25.4%) | 0.11 |

Self-report of DXA results

Results of self-report compared to actual DXA-result are tabulated in Table 2.

Table 2.

Self-report compared against registered DXA results, N=686

| DXA documenteda

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-report | Osteoporosis n=209 |

Osteopenia n=285 |

Normal BMD n=192 |

| Osteoporosis N=199 |

168 (80%) | 28 (10%) | 3 (2%) |

| Osteopenia N=292 |

40 (19%) | 228 (80%) | 24 (12%) |

| Normal BMD N=195 |

1 (1%) | 29 (10%) | 165 (86%) |

Excluding patients who did not know their DXA results (n=31)

According to WHO-criteria: ≤2.5 SD osteoporosis; −2.5 to −1 SD osteopenia; ≥1 SD normal BMD [15]

Of all patients, 4% (n=31) were completely unaware of their DXA results and excluded from the analysis. Agreement between self-reported and actual DXA results was very good (κ=0.83). Of patients with osteoporosis and osteopenia, 80% correctly reported their diagnosis. Patients with a normal BMD reported correct diagnosis in 86% of all cases. Thus, differences in results of self-report were not related to severity of diagnosis (p=0.4).

Correlates of correct understanding of DXA results included younger age (OR=0.97, 95% CI=0.95–0.99) and glucocorticoid treatment (OR=2.18, 95% CI=1.13–4.21; Table 3).

Table 3.

Correlates of correct understanding of DXA results (n=717)

| Unadjusted analysis (n=717)

|

Adjusted analysis (n=717)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p value | OR | 95% CI | p Value | |

| Age | 0.97 | 0.96–0.99 | 0.003 | 0.97 | 0.95–0.99 | 0.005 |

| Sex (female) | 0.80 | 0.42–1.54 | 0.50 | 0.74 | 0.38–1.44 | 0.38 |

| Current smoking | 1.15 | 0.75–1.75 | 0.52 | 1.16 | 0.75–1.79 | 0.49 |

| Current glucocorticoid treatment | 1.70 | 0.92–3.15 | 0.09 | 2.18 | 1.13–4.21 | 0.02 |

| Family history of osteoporosis in first degree relative | 1.21 | 0.84–1.74 | 0.31 | 1.23 | 0.83–1.83 | 0.30 |

| Prior fragility fracture | 0.82 | 0.56–1.19 | 0.25 | 1.07 | 0.70–1.62 | 0.77 |

| DXA results | ||||||

| Osteoporosis | 0.93 | 0.64–1.37 | 0.73 | 0.96 | 0.57–1.61 | 0.85 |

| Osteopenia | 0.84 | 0.59–1.20 | 0.34 | 0.80 | 0.51–1.27 | 0.35 |

| Normal BMD | 1.34 | 0.89–2.02 | 0.16 | 1.25 | 0.79–1.97 | 0.35 |

All variables in the table are included in the adjusted analysis

Proportion of patient-recommended treatment

Initiation and persistence with therapy

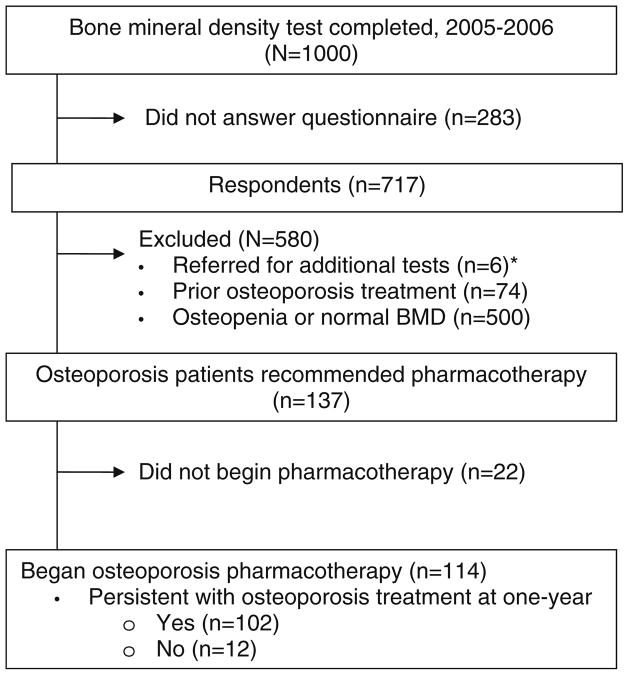

Of the 1,000 patients tested, 288 patients were identified as osteoporotic (T-score ≤2.5 of either hip or spine), and 137 patients were treatment naïve and not called in for further assessment; making them eligible, Fig. 2. Of the 137 eligible respondents recommended treatment, 121 (83%) initiated treatment: 91% with a bisphosphonate, 8% with strontium ranelate and <1% with teriparatide. One patient did not report type of osteoporosis pharmacotherapy. Of 121 patients beginning oral osteoporosis treatment after DXA, seven patients did not disclose whether they were still on treatment and thus were excluded from the analyses. Of the remaining 114 patients, 12 (11%) reported discontinuation of therapy and nine patients (75%) had stopped due to side effects.

Fig. 2.

Study chart: initiation and 1-year completion of osteoporosis pharmacotherapy in respondents recommended osteoporosis treatment; *e.g., vitamin D deficiency, hypogonadism, and suppressed TSH

In adjusted analysis, only correctly responding diagnosis as osteoporosis (OR 4.3, 95% CI 1.4–15.1) and higher perceived drug benefits scores (OR 1.5, 95% CI 1.1–1.9) were significantly associated with treatment initiation, Table 4. Higher perceived treatment benefits were also significantly associated with persistence with therapy (OR 1.8, 95% CI 1.2–2.7).

Table 4.

Correlates of treatment initiation and persistence with therapy (among those recommended treatment)

| Initiated osteoporosis treatment

|

Persisted with osteoporosis treatment

|

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted N=137

|

Adjusteda

N=114

|

Unadjusted N=114

|

Adjusteda

N=97

|

|||||||||||||

| OR | 95% CI | p Value | OR | 95% CI | p Value | OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | (95% CI) | p Value | |||||

| Age, mean (SD) | 0.99 | 0.94 | 1.05 | 0.77 | 0.96 | 0.90 | 1.03 | 0.24 | ||||||||

| Male | 1.57 | 0.19 | 13.22 | 0.68 | >999.999 | <0.001 | >999.999 | 0.97 | ||||||||

| Smoking (current) | 1.75 | 0.60 | 5.08 | 0.31 | 1.64 | 0.42 | 6.43 | 0.48 | ||||||||

| Glucocorticoid treatment (current) | 0.67 | 0.17 | 2.63 | 0.57 | 1.07 | 0.12 | 9.22 | 0.96 | ||||||||

| Family history in first degree relative | 2.40 | 0.76 | 7.58 | 0.14 | 2.33 | 0.55 | 9.91 | 0.25 | 0.50 | 0.15 | 1.67 | 0.26 | ||||

| Prior fragility fracture | 1.50 | 0.58 | 3.84 | 0.40 | 0.59 | 0.18 | 1.97 | 0.39 | ||||||||

| Early menopause | 0.89 | 0.27 | 2.93 | 0.85 | 1.00 | 0.20 | 4.98 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| Correctly report DXA test found osteoporosis | 3.29 | 1.24 | 8.74 | 0.02 | 4.33 | 1.24 | 15.09 | 0.02 | 0.93 | 0.19 | 4.63 | 0.93 | ||||

| Health status is good to excellentb | 1.06 | 0.43 | 2.65 | 0.90 | 3.00 | 0.77 | 11.72 | 0.11 | 4.98 | 0.51 | 48.92 | 0.169 | ||||

| Perceptions about benefitsc, Z-score | 1.52 | 1.18 | 1.96 | 0.001 | 1.45 | 1.11 | 1.90 | 0.006 | 1.86 | 1.27 | 2.73 | 0.001 | 1.80 | 1.19 | 2.73 | 0.006 |

| Drug treatment barriers (agreement) | ||||||||||||||||

| I am taking too many medications | 0.29 | 0.09 | 0.97 | 0.04 | 0.41 | 0.07 | 2.25 | 0.30 | 0.37 | 0.07 | 2.02 | 0.25 | ||||

| I have stomach problems that limit to the types of medicine I can tolerate | 1.07 | 0.39 | 2.98 | 0.89 | 0.15 | 0.04 | 0.56 | 0.004 | 0.32 | 0.06 | 1.68 | 0.178 | ||||

Adjusted for variables included in the table (p<0.2 in unadjusted analysis)

Self-report health status is excellent, very good, or good (compared to fair or poor)

Based on responses to three items on a five-point scale from strongly agree to strongly disagree: “Medical treatment can reduce the risk of broken bones”, “I would feel good about taking medications for osteoporosis”, “Medication can build strong bones”. Higher scores indicate stronger beliefs in the benefits of osteoporosis pharmacotherapy

Sensitivity analysis

Twenty-five percent (n=71, Table 1) of patients did not respond to our questionnaire, leading to a relative overrepresentation of patients with a family history of osteoporosis. Records showed that 44 non-respondents had been recommended treatment. In a sensitivity analysis, assuming that none of these patients initiated treatment would change our observed results of 83% initiating treatment to 64% (121/190). Similarly, the worst-case scenario in terms of persistence whereby all 44 non-respondents began and prematurely stopped pharmacotherapy would lead to an overall persistence of 64% (102/159).

Discussion

Better patient understanding of diagnosis following DXA examination has previously been linked to higher treatment rates and better adherence with the recommended treatment [15, 22, 23]. This is an important concern as poor refill compliance is associated with significantly higher risk of fractures [24]. We contacted 1,000 consecutive patients who had been examined by DXA in a publicly funded Danish osteoporosis clinic 1 year after the assessment. According to a new clinical strategy, patient and patients’ referring physician had received only mailed standardized information on diagnosis and treatment recommendations following DXA exam, a process without any verbal communication between the patient and the osteoporosis specialist. Patients also received personalized advice in writing (smoking cessation, avoid heavy lifting, etc.) tailored to their diagnosis and risk factor profile.

Our study revealed very good agreement between self-report and actual diagnosis, contrasting with prior investigations showing at best moderate agreement [14]. In our study, only one patient with osteoporosis had perceived results as normal, but uncertainty did exist on the subject of osteopenia. Predictors of correct understanding included younger age and current glucocorticoid use. We were encouraged to find that of all respondents, only 4% were not aware of DXA results, fewer than reported by other investigators assessing self-report after bone densitometry, where results were not communicated in writing to the patient and GP [14–16, 25].

Communication between healthcare system, patient and family physicians is essential to the delivery of health care and correlated to patient knowledge of the diagnosis and compliance with subsequent treatment [14]. Conveying the diagnosis and treatment recommendations in writing may serve the additional purpose of providing the family physicians with additional background knowledge on osteoporosis management, which is commonly perceived to be difficult [26–28]. This is supported by prior research indicating that direct disclosure of BMD results to the patients and GP lead to increased knowledge of BMD status [29]. Also, clinical reporting of results of bone densitometry to primary care physicians has been shown to increase use and understanding of bone densitometry and affect management of osteoporosis [30]. To our knowledge, no previous controlled studies have been conducted in Denmark in the field of osteoporosis treatment, written information letters and adherence. Multidisciplinary patient education in groups increased knowledge on osteoporosis in a previous Danish study but effects on adherence to treatment was not evaluated in this work [31]. In a Danish study on adherence to asthma medication use in patients with asthma, also a chronic condition, beliefs in effects of treatment was also found to be important for adherence. This is further supported by Horne et al. [32] who found patient perception of the balance between the necessity for the medication and concerns over its use to be a powerful predictor of adherence with treatment.

In the follow-up of 137 treatment-naïve osteoporosis patients, we found that drug initiation was significantly linked to perceived treatment benefits and patient understanding of DXA results. We further document that higher perceived benefits of osteoporosis pharmacotherapy was associated with persistence with therapy. Unadjusted results identified that agreement with the statement “I have stomach problems that limit the types of medicines I can tolerate” was negatively associated with persistence (OR=0.15, 95%CI 0.04–0.56, p=0.004). Although this association lost statistical significance after adjusting for other factors, the dominating reason for discontinuing treatment in this study was side effects, and our results are limited by lack of statistical power as we studied a small sample of patients and few reported to have stopped osteoporosis treatment. We therefore believe that side effects, and in particular, gastrointestinal tolerability may be an important contributing factor related to treatment persistence [33–36].

Our study is limited by including only a single DXA testing facility in a well-educated area of Denmark. We also excluded patients with osteopenia treated with glucocorticoids from our analysis that examined predictors of treatment initiation and persistence with therapy, yet these patients are recommended osteoporosis treatment. We are also limited by lack of control group, and by a small sample size of patients who discontinued treatment. Nonetheless, our study supports prior investigations of the critical importance of patient understanding of DXA results, a possibly modifiable factor in improving subsequent adherence to treatment [15]. Further analysis of perception of osteoporosis treatment is needed, as there may be other possible benefits and barriers to treatment that we did not include.

Persistence with osteoporosis treatment declines rapidly during the first 2 years of therapy [4, 37]. Strategies to improve adherence with therapy may reduce the burden of osteoporosis. We document that a modifiable factor, higher patient perceptions about the benefits of osteoporosis pharmacotherapy, is associated with treatment initiation and adherence to therapy. The benefits of written communication should be further evaluated in a randomized controlled trial and supplementary work is needed to confirm our findings. Interventions to improve patient perceptions about the benefits of pharmacotherapy may translate into better osteoporosis management.

In conclusion, our results confirm the critical importance of patient understanding of DXA results and improved communicative strategies, first for patients to understand that they need treatment, and also to convey the message about the critical importance of continued treatment. Engaging the general practitioner in communicating benefits of treatment may influence positively on the much needed improvements in adherence with pharmacotherapy and thus fracture prevention.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Cadarette holds a New Investigator Award in the Area of Aging and Osteoporosis from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Appendix

Example of personalized letter sent to patients and physicians regarding DXA test results. The original letters were written in Danish, and thus this is an example only based on a translation into English

Ms XX

Examination Date 12-05-2010

Your DXA bone density examination shows the following

The scan shows osteoporosis. (Other diseases such as lack of vitamin D can give rise to a similar result).

According to the information given to us, your risk factors for osteoporosis were the following

Smoking.

Comments to you from the doctor

The bone density is reduced to a degree corresponding to osteoporosis (bone fragility). Your risk of suffering a bone fracture within the next 10 years was estimated to about 10%, based on your DXA result, age, and sex. The risk of fractures can be reduced through medical treatment for osteoporosis. I recommend that you consult your GP for advice on this. In addition, smoking reduces bone mass and increases your risk of a fracture. In my opinion, the DXA scan should be repeated in 2 years.

Osteoporosis (bone fragility) is a loss of bone tissue and bone mineral, which leads to increased risk of broken bones after minor loads or falls. It is important to show due consideration and avoid lifting heavy burdens or bending the back while lifting. Preventing falls is important, particularly in the elderly. If you are working, you should seek advice from your doctor regarding how much lifting could be considered safe and whether some forms of work should not be undertaken. Medical treatment is possible in every case.

Detailed information about the DXA examination

You can find the detailed results below. The numbers are particularly important when you seek advice from health professionals, e.g., your GP.

T – score, hip −2.0 T – score, spine −3.0

T-score is a measure of whether one has osteoporosis. A more negative number indicates a lower bone density. Scores below −2.5 define osteoporosis.

Z – score, hip −1.2 Z – score, spine −2.1

Z-score is a measure of bone density compared with that of others of the same sex and age.

A positive number indicates that your bone density is above average—a negative number that it is below average. Most people have a Z-score between −2 and +2.

Yours sincerely,

Dr. Nn.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest None.

Contributor Information

D. Brask-Lindemann, Department of Endocrinology, Copenhagen University Hospital, Køge, Denmark

S. M. Cadarette, Leslie Dan Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada

P. Eskildsen, Department of Endocrinology, Copenhagen University Hospital, Køge, Denmark

B. Abrahamsen, Department of Endocrinology, Copenhagen University Hospital Gentofte, Hellerup, Denmark

References

- 1.Cooper A. Compliance with treatment for osteoporosis. Lancet. 2006;368:1648. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69691-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cramer JA, Silverman S. Persistence with bisphosphonate treatment for osteoporosis: finding the root of the problem. Am J Med. 2006;119:S12–S17. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Payer J, Killinger Z, Ivana S, Celec P. Therapeutic adherence to bisphosphonates. Biomed Pharmacother. 2007;61:191–193. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rabenda V, Mertens R, Fabri V, et al. Adherence to bisphosphonates therapy and hip fracture risk in osteoporotic women. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19(6):811–818. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0506-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siris ES, Selby PL, Saag KG, Borgstrom F, Herings RM, Silverman SL. Impact of osteoporosis treatment adherence on fracture rates in North America and Europe. Am J Med. 2009;122:S3–S13. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kothawala P, Badamgarav E, Ryu S, Miller RM, Halbert RJ. Systematic review and meta-analysis of real-world adherence to drug therapy for osteoporosis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82:1493–1501. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)61093-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cramer JA, Gold DT, Silverman SL, Lewiecki EM. A systematic review of persistence and compliance with bisphosphonates for osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18:1023–1031. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0322-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gold DT, Alexander IM, Ettinger MP. How can osteoporosis patients benefit more from their therapy? Adherence issues with bisphosphonate therapy. Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40:1143–1150. doi: 10.1345/aph.1G534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moller PK. Pricing and reimbursement of drugs in Denmark. Eur J Health Econ. 2003;4:60–65. doi: 10.1007/s10198-003-0165-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vestergaard P, Rejnmark L, Mosekilde L. Osteoporosis is markedly underdiagnosed: a nationwide study from Denmark. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16:134–141. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1680-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jaglal SB, Cameron C, Hawker GA, et al. Development of an integrated-care delivery model for post-fracture care in Ontario, Canada. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17:1337–1345. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0076-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haussler B, Gothe H, Gol D, Glaeske G, Pientka L, Felsenberg D. Epidemiology, treatment and costs of osteoporosis in Germany—the BoneEVA Study. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18:77–84. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0206-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lekkerkerker F, Kanis JA, Alsayed N, et al. Adherence to treatment of osteoporosis: a need for study. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18:1311–1317. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0410-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cadarette SM, Beaton DE, Gignac MA, Jaglal SB, Dickson L, Hawker GA. Minimal error in self-report of having had DXA, but self-report of its results was poor. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:1306–1311. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pickney CS, Arnason JA. Correlation between patient recall of bone densitometry results and subsequent treatment adherence. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16:1156–1160. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1818-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fitt NS, Mitchell SL, Cranney A, Gulenchyn K, Huang M, Tugwell P. Influence of bone densitometry results on the treatment of osteoporosis. CMAJ. 2001;164:777–781. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cadarette SM, Gignac MA, Jaglal SB, Beaton DE, Hawker GA. Access to osteoporosis treatment is critically linked to access to dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry testing. Med Care. 2007;45:896–901. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318054689f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lægemiddelstyrelsen. Kriterier for enkelttilskud til Ebixa, kolinesterasehæmmere, osteoporosemidler, Plavix og Persantin. Ugeskr Læger. 2003:2845. [Google Scholar]

- 19.WHO Study Group. Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis. Report of a WHO Study Group. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 1994;843:1–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cadarette SM, Gignac MA, Jaglal SB, Beaton DE, Hawker GA. Measuring patient perceptions about osteoporosis pharmacotherapy. BMC Res Notes. 2009;2:133. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-2-133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Byrt T. How good is that agreement? Epidemiology. 1996;7:561. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199609000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pressman A, Forsyth B, Ettinger B, Tosteson AN. Initiation of osteoporosis treatment after bone mineral density testing. Osteoporos Int. 2001;12:337–342. doi: 10.1007/s001980170099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tosteson AN, Grove MR, Hammond CS, et al. Early discontinuation of treatment for osteoporosis. Am J Med. 2003;115:209–216. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(03)00362-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Siris ES, Harris ST, Rosen CJ, et al. Adherence to bisphosphonate therapy and fracture rates in osteoporotic women: relationship to vertebral and nonvertebral fractures from 2 US claims databases. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81:1013–1022. doi: 10.4065/81.8.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kilding R, Eastell R, Peel N. Do patients receive appropriate information and treatment following bone mineral density measurements? Rheumatol (Oxf) 2002;41:1073–1074. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/41.9.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weiss TW, Siris ES, Barrett-Connor E, Miller PD, McHorney CA. Osteoporosis practice patterns in 2006 among primary care physicians participating in the NORA study. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18(11):1473–1480. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0408-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chenot R, Scheidt-Nave C, Gabler S, Kochen MM, Himmel W. German primary care doctors’ awareness of osteoporosis and knowledge of national guidelines. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2007;115:584–589. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-981454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jaglal SB, Carroll J, Hawker G, et al. How are family physicians managing osteoporosis? Qualitative study of their experiences and educational needs. Can Fam Physician. 2003;49:462–468. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Campbell MK, Torgerson DJ, Thomas RE, McClure JD, Reid DM. Direct disclosure of bone density results to patients: effect on knowledge of osteoporosis risk and anxiety level. Osteoporos Int. 1998;8:584–590. doi: 10.1007/s001980050103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stock JL, Waud CE, Coderre JA, et al. Clinical reporting to primary care physicians leads to increased use and understanding of bone densitometry and affects the management of osteoporosis. A randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:996–999. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-128-12_part_1-199806150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nielsen D, Ryg J, Nielsen W, Knold B, Nissen N, Brixen K. Patient education in groups increases knowledge of osteoporosis and adherence to treatment: a two-year randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.03.010. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Horne R, Weinman J. Patients’ beliefs about prescribed medicines and their role in adherence to treatment in chronic physical illness. J Psychosom Res. 1999;47:555–567. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(99)00057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lau E, Papaioannou A, Dolovich L, et al. Patients’ adherence to osteoporosis therapy: exploring the perceptions of postmenopausal women. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54:394–402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Switzer JA, Jaglal S, Bogoch ER. Overcoming barriers to osteoporosis care in vulnerable elderly patients with hip fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2009;23:454–459. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e31815e92d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tosteson AN, Do TP, Wade SW, Anthony MS, Downs RW. Persistence and switching patterns among women with varied osteoporosis medication histories: 12-month results from POSSIBLE US. Osteoporos Int. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s00198-009-1133-5. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Warriner AH, Curtis JR. Adherence to osteoporosis treatments: room for improvement. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2009;21:356–362. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e32832c6aa4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huybrechts KF, Ishak KJ, Caro JJ. Assessment of compliance with osteoporosis treatment and its consequences in a managed care population. Bone. 2006;38:922–928. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]