Organizations around the world produce clinical practice guidelines at an astonishing pace, with great effort and at substantial cost.1 Unfortunately, despite broad dissemination efforts, large gaps remain between guideline recommendations and real-world practice across health systems, practitioner and patient types, and diseases. 2 Conventional approaches to guideline implementation use the guideline as a starting point and manipulate factors external to the guideline (e.g., provider knowledge and practice workflow) to optimize its uptake.1 However, it is becoming increasingly clear that certain features of the guideline itself may also influence its uptake. We explore how the language and format used in a guideline may affect how likely it is to be followed in real-world practice. We offer practical tips to optimize these features in an effort to increase a guideline’s uptake.

Why don’t clinicians use guidelines?

Clinicians complain that guidelines are too lengthy, ambiguous and complex3–5 and that they are presented in too rigid a fashion for practical application in individual cases.6–9 In a review of 41 qualitative studies, incomprehensible structure, poor usability and poor local applicability of guidelines were identified as the key barriers to their implementation.10 In particular, primary care physicians perceive barriers and facilitators to guideline uptake almost exclusively according to their format, language and usability.11 Accordingly, the style in which a guideline is written (e.g., providing suggested actions rather than prohibitive rules) influences how it is received and whether it will be followed.12 In an observational study involving general practitioners in the Netherlands, vague and imprecisely defined recommendations were followed in 36% of clinical decisions, whereas clear recommendations were followed in 67% of decisions.13

The influence of these “intrinsic” guideline characteristics14 on clinicians’ intention to practise and their actual practise of recommended behaviours has been recognized for more than a decade.13,15–17 Recently, an extensive review of these characteristics18 has enabled the development and validation of a set of key principles to optimize the implementability of guidelines — the Guideline Implementability for Decision Excellence Model (GUIDE-M) (Appendix 1, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.151102/-/DC1). These principles include (a) credible and representative developers of guideline content, (b) high-quality synthesis and contextualization of evidence for creating guideline content and (c) optimal use of language and format to convey recommendations.19

Why are the language and format of guidelines so important?

A growing body of literature suggests that the language of recommendations has to be simple, clear and persuasive to reduce cognitive load, increase understanding and retention, and render convincing and salient arguments.18 The level of complexity is inversely proportional to overall guideline adoption20,21 and adherence to recommendations.22,23

At the same time, a number of formatting aspects of guidelines can help to promote their use in practice.12,24 These include presentation aspects such as a user-friendly layout (e.g., considering document length and the placement of visual elements), structure (e.g., bundling information and matching the order and flow of recommendations to that of real-world practice) and how information is best visualized (e.g., conveying complex recommendations through tables, graphs and flowcharts). Some of these common design principles for scientific communication have an empirical foundation, whereas many others are derived from best practices and user preferences. However, because most formatting principles are based on cognitive processes, they are likely to be generalizable across disciplines and contexts.18

Studies have shown that efforts to improve language and format according to best evidence can improve the uptake of recommendations. In a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of guideline writing styles, a more specific and actionable recommendation increased appropriate ordering of tests and decreased inappropriate ordering.25 Furthermore, compared with no guideline at all, the nonspecific guideline led to a decrease in appropriate ordering,25 which suggests that a poorly written guideline may be harmful. In another RCT, evidence-based improvements to language style and specificity of recommendations in a guideline led to users having stronger intentions to implement the recommendations, greater perceived control over their ability to implement guideline-recommended behaviours and more positive attitudes toward the guideline, compared with the original version.17

Examples from recent guidelines

To illustrate some of these concepts, we have chosen examples from the latest guidelines for three of the most common chronic conditions in Canada: diabetes, asthma and ischemic heart disease.26 In each example, we display a recommendation from a published guideline and highlight problem areas related to the corresponding language or format “construct” (where relevant, we also highlight issues related to the creation of content). We then present a suggested revision of the recommendation that attempts to address these problems. (More detailed descriptions of the constructs are presented in Appendix 2, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.151102/-/DC1.) A member of each original guideline committee was asked to comment on these issues and to provide content expertise in crafting the revised recommendations (A.Y.Y.C. for diabetes, K.A.C. for ischemic heart disease, and L.P.B. for asthma). Although format is no less important than language, each example raised multiple language-related issues, but only a few format-related ones; therefore, most of the highlighted issues relate to language.

Example 1

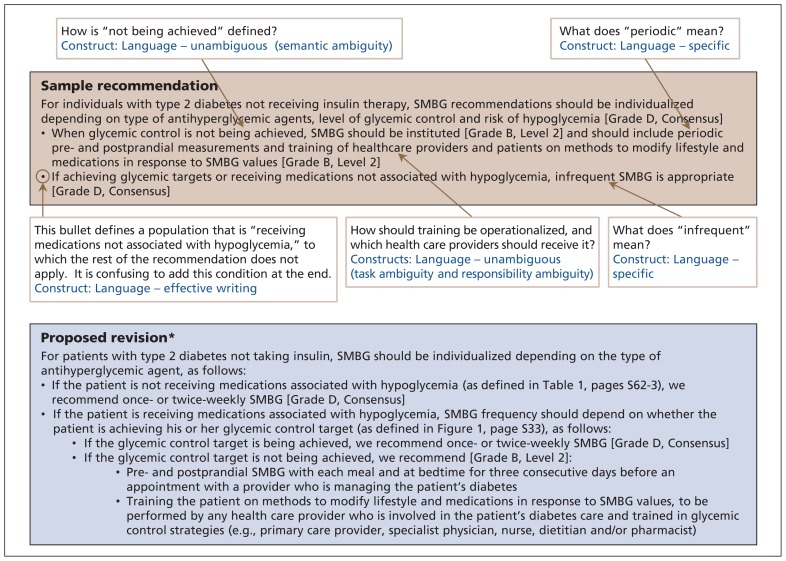

Figure 1 features several examples of ambiguous language in a recommendation from the Canadian Diabetes Association 2013 clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and management of diabetes in Canada.27 Ambiguity arises when guidelines do not clearly and consistently specify recommended actions and parameters on which decisions should be based.23,28 This can lead to vague recommendations that are unlikely to guide practice in a meaningful way.29 The first bullet point in the recommendation in Figure 1 is conditional on a situation in which “glycemic control is not being achieved.” Failure to provide a definition of suboptimal glycemic control introduces semantic ambiguity, whereby different users of the guideline may reasonably interpret this condition in different ways. The same bullet point recommends “training of healthcare providers and patients.” However, both the nature of this training and how this task should be operationalized are unclear23 (e.g., should health care providers receive the training first and then train their patients, or should both health care providers and patients undergo the same training simultaneously?), which introduces task ambiguity.

Figure 1:

Recommendation for monitoring glycemic control in patients with diabetes, taken from the 2013 clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and management of diabetes in Canada (page S37).27 Beige box: original recommendation with identified problems and corresponding constructs. Blue box: proposed revision. *The proposed revision is for explanatory purposes only and should not be interpreted as an actual guideline recommendation. SMBG = self-monitoring of blood glucose. (See Appendix 2 for definitions of the constructs, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.151102/-/DC1.)

The recommendation in Figure 1 also fails to identify which of the several possible health care providers typically involved in diabetes care should undergo the training or assume responsibility for subsequent patient training (e.g., primary care physicians might think that the recommendation is aimed exclusively at specialists, and vice versa). This introduces responsibility ambiguity.23

Ambiguity can be overcome by using propositional and semantic analysis techniques (which systematically identify ambiguous areas in the text that lead to misunderstandings)30 and subsequent disambiguation (establishment of a single semantic interpretation for a recommended statement).28 Ultimately, each recommendation should specify what action is required, by whom and when (under what specific conditions).16,31

Similarly, recommendations for “periodic pre-and postprandial measurements” (first bullet point in Figure 1) and “infrequent [self-monitoring of blood glucose]” (second bullet point) represent a failure to use specific language. Use of “periodic” and “infrequent” leaves the recommendation open to broad interpretation. In turn, this can lead to reduced adherence or increased practice variation, or both.32 When guideline developers intend to establish “ceilings and floors” around specific actions, use of concrete statements to clarify frequencies and quantities increases the extent to which information is understood and remembered.16

Example 2

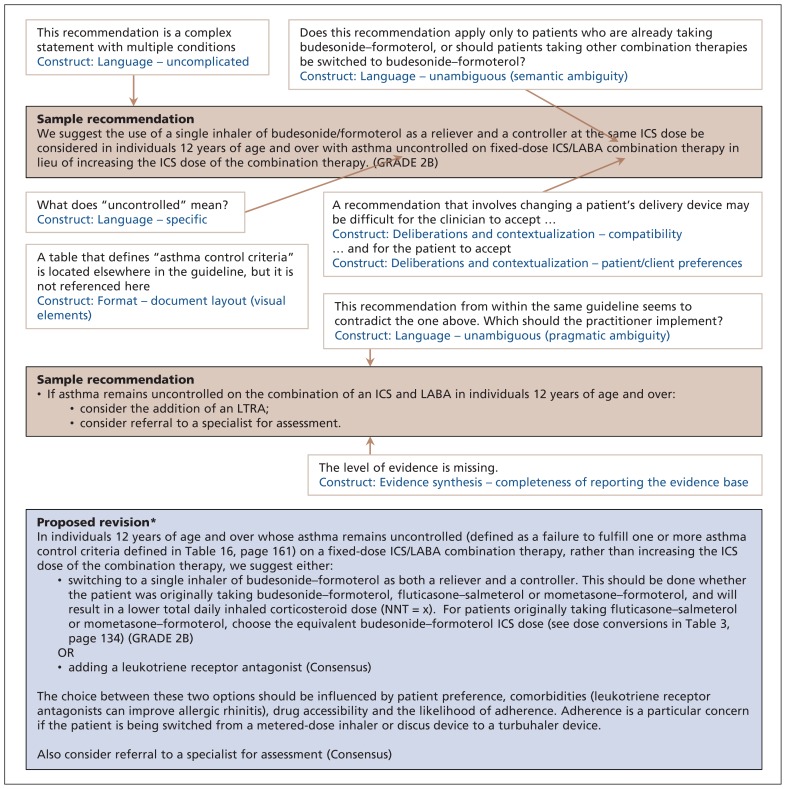

Figure 2 has several examples of implementability problems related to how guideline content was created. The sample recommendations are from the Canadian Thoracic Society 2012 guideline on the diagnosis and management of asthma.33 The recommendation for clinicians to change their patient’s inhaler device challenges compatibility with existing prescribing habits. Because many clinicians may have a preferred product in each class of inhalers that they are most familiar with, implementation could be limited by both resistance to this change34 and the cognitive load associated with adopting this change.35 Also, this represents a new norm, and changes in practice that are incompatible with existing norms are less likely to be adopted.13,36–38 In situations where such recommendations are unavoidable, implementability can be improved by clearly laying out exactly what changes are required39 and how the innovation will improve the provider’s performance.40

Figure 2:

Recommendations for the management of patients with asthma uncontrolled on fixed-dose combination ICS/LABA therapy, taken from the Canadian Thoracic Society 2012 guideline on the diagnosis and management of asthma (p. 144 and 158).33 Beige boxes: original recommendations with identified problems and corresponding constructs. Blue box: proposed revision. *The proposed revision is for explanatory purposes only and should not be interpreted as an actual guideline recommendation. ICS = inhaled corticosteroid, LABA = long-acting β2-agonist, LTRA = leukotriene receptor agonist.

The recommendation also raises concerns about patient preferences. Patients may be reluctant to change their inhaler device because of personal preference and concerns about adverse effects.41,42 The guideline developers themselves acknowledged that a switch to budesonide– formoterol has been associated with a twofold increase in discontinuation due to adverse effects. 33,43 Pressure on physicians to accommodate patient preference plays an important role in guideline adherence.44 Accordingly, avoiding blanket recommendations in favour of a menu of options allowing clinicians to consider potentially divergent patient choices and values would be expected to improve adherence.31,45,46 This not only reflects users’ clinical reality, but it also presents an opportunity for shared decision-making. 47 Understanding of the breadth of patient preferences can be improved further through direct patient input during guideline development. 48,49 Guideline developers can also include metrics such as the number needed to treat or harm, which clinicians can use to empower patients to apply their personal values in the shared decision-making process.50

We also noted that a different section of the same guideline represented in Figure 2 offered a contradictory recommendation (initiation of a leukotriene receptor antagonist) for the same clinical scenario (patients whose asthma is not controlled with the combination of an inhaled corticosteroid and long-acting β-agonist). This contradiction represents a case of pragmatic ambiguity, leaving readers confused as to which of the two recommendations should be applied.51 The guideline developers could instead have presented both possible courses of action with use of the boolean operator “or”20 and a list of conditions indicating when one option should be favoured over the other. The contradictory recommendation was also presented without any level of evidence, thereby failing to meet criteria for completeness of reporting the evidence base. The omission leaves readers unsure about both the quality of underlying evidence and the strength of the corresponding recommendation and lessens the likelihood they will follow the recommendation.31,52

Example 3

Appendix 3 (available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.151102/-/DC1) contains several examples of both language and format concerns. The sample recommendations are from the 2014 Canadian Cardiovascular Society guidelines for the diagnosis and management of stable ischemic heart disease.53 In terms of language, one recommendation suggests the addition of a nitrate when treatment with a β-blocker and/or a long-acting calcium-channel blocker “is not tolerated or contraindicated.” Failure to provide a definition or example of intolerance or contraindication constitutes exception ambiguity, whereby the circumstances in which clinicians should make an “exception” to this recommendation (because the risk of the medication outweighs its benefits) are not clearly defined.54

In another example, a negative recommendation (describing what treatments not to use for angina management) is interspersed with positive recommendations. The word “not” in front of a recommendation is considered a “killer” term, because it is both easy and dangerous to overlook.55 At best, this creates confusion, slows down the reader56 and reduces guideline acceptance57,58 and compliance.59 At worst, it leads to an erroneous interpretation of the recommendations. Accordingly, effective writing requires negative recommendations to be clearly separated from positive ones.55

In another recommendation regarding implementation and optimization of medical therapy, the timelines, patient population and assessment criteria to determine adequacy of therapy are all described in a single sentence (Appendix 3). This recommendation includes multiple steps37,57 in a complex decision tree13,36,60 as well as different conditional factors that should influence the clinician’s approach.13,61 This type of complexity hinders understanding and persuasiveness and may render recommendations more difficult to accept22,62 and thus less likely to be implemented.37,63 Managing this complexity to produce uncomplicated recommendations requires “atomization” — the process of extracting and presenting individual concepts from the complex recommendation.64

The same recommendation refers to “high-risk features.” Although not referenced specifically, a table located elsewhere in the guideline clearly defines such features. This is a format issue, whereby visual elements (e.g., a table) that is required to understand a recommendation should be easily and quickly accessible to readers.65,66 This promotes simplicity and ease of use,12,24,67 both of which influence real-world guideline uptake.68,69

Finally, the individual recommendations presented in Appendix 3 are a complex set of inter-related conditional statements and options that must be considered together in order to manage an individual patient’s angina. This amount and complexity of information can easily result in “information overload,” whereby users become so saturated that important information is lost and the person’s interest in the information is diminished.70 Best information display practices attempt to shift cognitive load to the human perceptual system by presenting information in a visual form that facilitates exploration and understanding and leads to better, faster and more confident decisions.71 In this case, a flowchart of the clinical decision pathway, such as the one we have created (Appendix 4, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.151102/-/DC1), would enable an understanding of how individual recommendations relate to one another.72 It could be structured in a sequence that mimics a real patient encounter, enabling users to follow a more natural mapping process and to assimilate information better.73 When the decision logic is complex and the temporal sequence of activities is unclear,31 use of such strategies can improve guideline utilization.74

Where do guideline developers go from here?

Improving the intrinsic characteristics of guidelines will require effort by professional societies that produce guidelines, guideline writers themselves and guideline scientists. The first steps are to create awareness among guideline societies and to convince guideline writers of the importance of these issues. Practically, these stakeholders will need to allocate additional time and resources for application of language and format principles in the guideline process. Ideally, end-users of a guideline should also be involved in this process. Recent work suggests that primary care physicians can be successfully engaged in objectively assessing language and format attributes of recommendations and improving these according to their preferences11 (a worksheet from this process is included in Appendix 5, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.151102/-/DC1). Efforts could be initiated by individual guideline committees. Alternatively, medical societies that produce multiple guidelines may choose to build a team consisting of intended users (e.g., primary care providers), graphic designers and professional writers tasked with assessing and optimizing draft recommendations for multiple guidelines.13 As a final validation step, optimized recommendations could be pilot tested by real-world users given clinical vignettes to gauge their understanding of the recommendations, 75 with a mechanism for structured feedback for further improvements.

Conclusion

Poor uptake of guidelines continues to be a major challenge across health systems, greatly limiting our ability to deliver the benefits of advancing research to patients. We believe that approaches that focus on factors external to the guideline as well as those that consider intrinsic guideline characteristics will be needed to tackle this challenge. However, given that conventional external implementation strategies of varying cost and complexity have had only modest impacts on care, addressing how guidelines are written may be the simpler and more cost-effective intervention to augment their uptake. Furthermore, a basic set of such principles is likely to be applicable across content areas and thus easier to implement widely than conventional implementation approaches, which are context dependent. Guideline scientists and guideline developers need to collaborate to establish and refine methods to operationalize these concepts easily, and to measure the impact objectively on both guideline uptake and patient-relevant outcomes.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Drs. Marie Faughnan and Sharon Straus for their helpful comments.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: Monika Kastner is an associate editor for CMAJ and was not involved in the editorial decision-making process for this article.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Samir Gupta conceived of the analysis. Samir Gupta, Navjot Rai and Monika Kastner reviewed the literature, identified guideline examples, analyzed recommendations and drafted the manuscript. Alice Cheng, Kim Connelly and Louis-Phillipe Boulet helped to craft revised recommendations. Onil Bhattacharyya, Alan Kaplan and Melissa Brouwers helped to interpret all of the data. All of the authors revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, approved the final version to be published and agreed to act as guarantors of the work.

Competing interests: Samir Gupta is vice-chair of the Canadian Thoracic Society’s Canadian Respiratory Guidelines Committee; Alice Cheng has received speaker fees from, and is a paid member of advisory boards for, AstraZeneca, Abbott Diabetes, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi and Valeant; she has also received speaker fees from Becton Dickinson and is a paid member of an advisory board for Servier. No other competing interests were declared. Louis-Philippe Boulet has received nonprofit research grants provided to his institution from Altair, Amgen, Asmacure, AstraZeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Boston Scientific, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Ono Pharma, Schering and Wyeth; support for investigator-generated studies from Takeda, Merck and Boehringer-Ingelheim; consulting fees and advisory board honoraria from Astra Zeneca and Novartis; royalties as coauthor for UpToDate card on occupational asthma; nonprofit grants to produce educational materials from AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck Frosst, Boehringer-Ingelheim and Novartis; speaker fees from AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck and Novartis; and travel support to attend meetings from Novartis and Takeda. In addition, Louis-Philippe Boulet is a member of the Canadian Thoracic Society’s Canadian Respiratory Guidelines Committee; chair of the Global Initiative for Asthma’s Guidelines Dissemination and Implementation Committee; and Laval University Chair on Knowledge Transfer, Prevention and Education in Respiratory and Cardiovascular Health. No other competing interests were declared.

Funding: This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR; application no. 236225, competition no. 201010KPC). Samir Gupta is supported by the Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute of St. Michael’s Hospital and the University of Toronto. Navjot Rai was supported by the Comprehensive Research Experience for Medical Students Program, Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto. Onil Bhattacharrya holds the Frigon Blau Chair in Family Medicine Research at Women’s College Hospital. Kim Connelly is supported by a CIHR New Investigator Award. Monika Kastner is supported by an Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care Health System Research Fund Capacity Award.

References

- 1.Grimshaw JM, Thomas RE, MacLennan G, et al. Effectiveness and efficiency of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies. Health Technol Assess 2004;8:iii–iv, 1–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, et al. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. N Engl J Med 2003; 348:2635–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mazza D, Russell SJ. Are GPs using clinical practice guidelines? Aust Fam Physician 2001;30:817–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lugtenberg M, Zegers-van Schaick JM, Westert GP, et al. Why don’t physicians adhere to guideline recommendations in practice? An analysis of barriers among Dutch general practitioners. Implement Sci 2009;4:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Francke AL, Smit MC, de Veer AJ, et al. Factors influencing the implementation of clinical guidelines for health care professionals: a systematic meta-review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2008;8:38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farquhar CM, Kofa EW, Slutsky JR. Clinicians’ attitudes to clinical practice guidelines: a systematic review. Med J Aust 2002; 177: 502–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith L, Walker A, Gilhooly K. Clinical guidelines of depression: a qualitative study of GPs’ views. J Fam Pract 2004;53:556–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Veldhuijzen W, Ram PM, van der Weijden T, et al. Characteristics of communication guidelines that facilitate or impede guideline use: a focus group study. BMC Fam Pract 2007;8:31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lugtenberg M, Burgers JS, Besters CF, et al. Perceived barriers to guideline adherence: a survey among general practitioners. BMC Fam Pract 2011;12:98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cochrane LJ, Olson CA, Murray S, et al. Gaps between knowing and doing: understanding and assessing the barriers to optimal health care. J Contin Educ Health Prof 2007;27:94–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kastner M, Estey E, Hayden L, et al. The development of a guideline implementability tool (GUIDE-IT): a qualitative study of family physician perspectives. BMC Fam Pract 2014;15:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carlsen B, Glenton C, Pope C. Thou shalt versus thou shalt not: a meta-synthesis of GPs’ attitudes to clinical practice guidelines. Br J Gen Pract 2007;57:971–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grol R, Dalhuijsen J, Thomas S, et al. Attributes of clinical guidelines that influence use of guidelines in general practice: observational study. BMJ 1998;317:858–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gagliardi AR, Brouwers MC, Bhattacharyya OK. The Guideline Implementability Research and Application Network (GIRAnet): an international collaborative to support knowledge exchange: study protocol. Implement Sci 2012;7:26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shiffman RN, Dixon J, Brandt C, et al. The GuideLine Implementability Appraisal (GLIA): development of an instrument to identify obstacles to guideline implementation. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2005;5:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Michie S, Johnston M. Changing clinical behaviour by making guidelines specific. BMJ 2004;328:343–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Michie S, Lester K. Words matter: increasing the implementation of clinical guidelines. Qual Saf Health Care 2005;14:367–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kastner M, Bhattacharyya O, Hayden L, et al. Guideline uptake is influenced by six implementability domains for creating and communicating guidelines: a realist review. J Clin Epidemiol 2015; 68:498–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brouwers MC, Makarski J, Kastner M, et al. ; GUIDE-M Research Team. The Guideline Implementability Decision Excellence Model (GUIDE-M): a mixed methods approach to create an international resource to advance the practice guideline field. Implement Sci 2015;10:36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scott SD, Plotnikoff RC, Karunamuni N, et al. Factors influencing the adoption of an innovation: an examination of the uptake of the Canadian Heart Health Kit (HHK). Implement Sci 2008;3:41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tornatzky LG, Klein KJ. Innovation characteristics and innovation adoption-implementation: a meta-analysis of findings. IEEE Trans Eng Manage 1982;29:28–43. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rashidian A, Eccles MP, Russell I. Falling on stony ground? A qualitative study of implementation of clinical guidelines’ prescribing recommendations in primary care. Health Policy 2008; 85:148–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gurses AP, Marsteller JA, Ozok AA, et al. Using an interdisciplinary approach to identify factors that affect clinicians’ compliance with evidence-based guidelines. Crit Care Med 2010;38(Suppl): S282–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gagliardi AR, Brouwers MC, Palda VA, et al. How can we improve guideline use? A conceptual framework of implementability. Implement Sci 2011;6:26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shekelle PG, Kravitz RL, Beart J, et al. Are nonspecific practice guidelines potentially harmful? A randomized comparison of the effect of nonspecific versus specific guidelines on physician decision making. Health Serv Res 2000;34:1429–48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chronic disease facts and figures. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada; 2015. Available: www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/cd-mc/facts_figures-faits_chiffres-eng.php (accessed 2015 Aug. 29). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Canadian Diabetes Association Clinical Practice Guidelines Expert Committee. Canadian Diabetes Association 2013 clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and management of diabetes in Canada. Can J Diabetes 2013;37(Suppl 1):S1–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shiffman RN, Michel G, Essaihi A, et al. Bridging the guideline implementation gap: a systematic, document-centered approach to guideline implementation. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2004;11: 418–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Flanders SA, Halm EA. Guidelines for community-acquired pneumonia: Are they reflected in practice? Treat Respir Med 2004; 3:67–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patel VL, Arocha JF, Diermeier M, et al. Methods of cognitive analysis to support the design and evaluation of biomedical systems: the case of clinical practice guidelines. J Biomed Inform 2001;34:52–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosenfeld RM, Shiffman RN. Clinical practice guideline development manual: a quality-driven approach for translating evidence into action. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2009;140 (Suppl 1):S1–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Codish S, Shiffman RN. A model of ambiguity and vagueness in clinical practice guideline recommendations. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2005:146–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lougheed MD, Lemiere C, Ducharme FM, et al. ; Canadian Thoracic Society Asthma Clinical Assembly. Canadian Thoracic Society 2012 guideline update: diagnosis and management of asthma in preschoolers, children and adults. Can Respir J 2012;19:127–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Redelmeier DA, Ferris LE, Tu JV, et al. Problems for clinical judgement: introducting cognitive psychology as one more basic science. CMAJ 2001;164:358–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Farrington J. From the research: myths worth dispelling seven plus or minus two. Performance Improvement Quarterly 2011; 23:113–6. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burgers JS, Grol RP, Zaat JO, et al. Characteristics of effective clinical guidelines for general practice. Br J Gen Pract 2003; 53:15–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Foy R, MacLennan G, Grimshaw J, et al. Attributes of clinical recommendations that influence change in practice following audit and feedback. J Clin Epidemiol 2002;55:717–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lugtenberg M, Burgers JS, Zegers-van Schaick JM, et al. Guidelines on uncomplicated urinary tract infections are difficult to follow: perceived barriers and suggested interventions. BMC Fam Pract 2010;11:51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McAlister FA, van Diepen S, Padwal RS, et al. How evidence-based are the recommendations in evidence-based guidelines? PLoS Med 2007;4:e250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thompson RL, Higgins CA, Howell JM. Personal computing: toward a conceptual model of utilization. Manage Inf Syst Q 1991; 15:125–43. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rau JL. Determinants of patient adherence to an aerosol regimen. Respir Care 2005;50:1346–56, discussion 57–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Björnsdóttir US, Gizurarson S, Sabale U. Potential negative consequences of non-consented switch of inhaled medications and devices in asthma patients. Int J Clin Pract 2013;67:904–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cates CJ, Lasserson TJ. Combination formoterol and budesonide as maintenance and reliever therapy versus inhaled steroid maintenance for chronic asthma in adults and children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;(2):CD007313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tan KB. Clinical practice guidelines: a critical review. Int J Health Care Qual Assur Inc Leadersh Health Serv 2006;19:195–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shaneyfelt TM, Mayo-Smith MF, Rothwangl J. Are guidelines following guidelines? The methodological quality of clinical practice guidelines in the peer-reviewed medical literature. JAMA 1999;281:1900–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tudiver F, Guibert R, Haggerty J, et al. What influences family physicians’ cancer screening decisions when practice guidelines are unclear or conflicting? J Fam Pract 2002;51:760. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shapiro DW, Lasker RD, Bindman AB, et al. Containing costs while improving quality of care: the role of profiling and practice guidelines. Annu Rev Public Health 1993;14:219–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Verkerk K, Van Veenendaal H, Severens JL, et al. Considered judgement in evidence-based guideline development. Int J Qual Health Care 2006;18:365–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.SIGN 50: a guideline developer’s handbook. Edinburgh: Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network; 2015. Available: www.sign.ac.uk/pdf/sign50.pdf (accessed 2015 Dec. 3). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hahn DL. Importance of evidence grading for guideline implementation: the example of asthma. Ann Fam Med 2009;7:364–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Goud R, van Engen-Verheul M, de Keizer NF, et al. The effect of computerized decision support on barriers to guideline implementation: a qualitative study in outpatient cardiac rehabilitation. Int J Med Inform 2010;79:430–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ 2010;182:E839–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mancini GB, Gosselin G, Chow B, et al. ; Canadian Cardiovascular Society. Canadian Cardiovascular Society guidelines for the diagnosis and management of stable ischemic heart disease. Can J Cardiol 2014;30:837–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gurses AP, Seidl KL, Vaidya V, et al. Systems ambiguity and guideline compliance: a qualitative study of how intensive care units follow evidence-based guidelines to reduce healthcare-associated infections. Qual Saf Health Care 2008;17:351–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gawande A. The checklist manifesto: how to get things right. New York: Metropolitan Books; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gaetner-Johnston L. Best practices for bullet points. Seattle: Syntax Training; 2005. Available: www.businesswritingblog.com/business_writing/2005/12/the_best_of_bul.html (accessed 2016 Jan. 27). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Milner KK, Valenstein M. A comparison of guidelines for the treatment of schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv 2002;53:888–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Watine J, Friedberg B, Nagy E, et al. Conflict between guideline methodologic quality and recommendation validity: a potential problem for practitioners. Clin Chem 2006;52:65–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gagliardi AR, Brouwers MC, Palda VA, et al. An exploration of how guideline developer capacity and guideline implementability influence implementation and adoption: study protocol. Implement Sci 2009;4:36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.van der Weijden T, Grol RP, Knottnerus JA. Feasibility of a national cholesterol guideline in daily practice. A randomized controlled trial in 20 general practices. Int J Qual Health Care 1999; 11:131–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Garfield FB, Garfield JM. Clinical judgment and clinical practice guidelines. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2000;16:1050–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ball K. Surgical smoke evacuation guidelines: compliance among perioperative nurses. AORN J 2010;92:e1–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Parry G, Cape J, Pilling S. Clinical practice guidelines in clinical psychology and psychotherapy. Clin Psychol Psychother 2003; 10:337–51. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shiffman RN, Michel G, Essaihi A, et al. Using a guideline-centered approach for the design of a clinical decision support system to promote smoking cessation. Stud Health Technol Inform 2004;101:152–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Conroy M, Shannon W. Clinical guidelines: their implementation in general practice. Br J Gen Pract 1995;45:371–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Silayoi P, Speece M. The importance of packaging attributes: a conjoint analysis approach. Eur J Mark 2007;41:1495–517. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stone TT, Schweikhart SB, Mantese A, et al. Guideline attribute and implementation preferences among physicians in multiple health systems. Qual Manag Health Care 2005;14:177–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tong A. Clinical guidelines: Can they be effective? Nurs Times 2001;97:III–IV. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Grimshaw JM, Russell IT. Effect of clinical guidelines on medical practice: a systematic review of rigorous evaluations. Lancet 1993; 342:1317–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lehtonen J. The Information Society and the new competence. Am Behav Sci 1988;32:104–11. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lurie NH. Visual representation: implications for decision making. J Mark 2007;71:160–77. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tu SW, Campbell J, Musen MA. The structure of guideline recommendations: a synthesis. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2003:679–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kushniruk AW, Patel VL. Cognitive and usability engineering methods for the evaluation of clinical information systems. J Biomed Inform 2004;37:56–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Turner T, Misso M, Harris C, et al. Development of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (CPGs): comparing approaches. Implement Sci 2008;3:45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chatterjee A, Bhattacharyya O, Persaud N. How can Canadian guideline recommendations be tested? CMAJ 2013;185:465–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]