Abstract

In plants, the chloroplast is the organelle that conducts photosynthesis. It has been known that chloroplast is involved in virus infection of plants for approximate 70 years. Recently, the subject of chloroplast-virus interplay is getting more and more attention. In this article we discuss the different aspects of chloroplast-virus interaction into three sections: the effect of virus infection on the structure and function of chloroplast, the role of chloroplast in virus infection cycle, and the function of chloroplast in host defense against viruses. In particular, we focus on the characterization of chloroplast protein-viral protein interactions that underlie the interplay between chloroplast and virus. It can be summarized that chloroplast is a common target of plant viruses for viral pathogenesis or propagation; and conversely, chloroplast and its components also can play active roles in plant defense against viruses. Chloroplast photosynthesis-related genes/proteins (CPRGs/CPRPs) are suggested to play a central role during the complex chloroplast-virus interaction.

Keywords: chloroplast, plant virus, protein interaction, virus infection, plant defense

Introduction

Plant viruses, as obligate biotrophic pathogens, attack a broad range of plant species utilizing host plants' cellular apparatuses for protein synthesis, genome replication and intercellular and systemic movement in order to support their propagation and proliferation. Virus infection usually causes symptoms resulting in morphological and physiological alterations of the infected plant hosts, which always incurs inferior performance such as the decreased host biomass and crop yield loss.

The most common viral symptom is leaf chlorosis, reflecting altered pigmentation and structural change of chloroplasts. Viral influence on chloroplast structures and functions usually leads to depleted photosynthetic activity. Since the first half of the twentieth century, an increasing number of reports on a broad range of plant-virus combinations have revealed that virus infection inhibits host photosynthesis, which is usually associated with viral symptoms (Kupeevicz, 1947; Owen, 1957a,b, 1958; Hall and Loomis, 1972; Mandahar and Garg, 1972; Reinero and Beachy, 1989; Balachandran et al., 1994b; Herbers et al., 2000; Rahoutei et al., 2000; Guo et al., 2005; Christov et al., 2007; Kyseláková et al., 2011). It is suggested that modification of photosynthesis is a common and conserved strategy for virus pathogenesis to facilitate infection and to establish an optimal niche (Gunasinghe and Berger, 1991). The disturbance of chloroplast components and functions may be responsible for the production of chlorosis symptoms that are associated with virus infection (Manfre et al., 2011).

A series of typical changes followed by chlorotic symptoms imply the occurrence of chloroplast-virus interactions. These changes include (1) fluctuation of chlorophyll fluorescence and reduced chlorophyll pigmentation (Balachandran et al., 1994a), (2) inhibited photosystem efficiency (Lehto et al., 2003), (3) imbalanced accumulation of photoassimilates (Lucas et al., 1993; Olesinski et al., 1995, 1996; Almon et al., 1997), (4) changes in chloroplast structures and functions (Bhat et al., 2013; Otulak et al., 2015), and (5) repressed expression of nuclear-encoded chloroplast and photosynthesis-related genes (CPRGs) (Dardick, 2007; Mochizuki et al., 2014a), (6) direct binding of viral components with chloroplast factors (Shi et al., 2007; Bhat et al., 2013; Zhao et al., 2013).

In fact, the chloroplast itself is a chimera of components of various origins coming from its bacterial ancestors, viruses and host plants. For example, chloroplast contains the nuclear-encoded phage T3/T7-like RNA polymerase (Hedtke et al., 1997; Kobayashi et al., 2001; Filée and Forterre, 2005). It is not surprising that chloroplast has an important role in plant-virus interactions. Indeed, more and more chloroplast factors have been identified to interact with viral components (Table 1). These factors are involved in virus replication, movement, symptoms or plant defense, suggesting that viruses have evolved to interact with chloroplast.

Table 1.

Chloroplast factors interacting with virus nucleic acids or proteins.

| Plant Virus* | Virus components | Chloroplast factors | Subcellular localization | Biological process | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ssRNA POSITIVE-STRAND VIRUSES | |||||

| Potexvirus/Alphaflexiviridae | |||||

| Alternanthera mosaic virus (AltMV) | TGB3 | Chloroplast membrane | Chloroplast | Cell-to-cell movement, long-distance movement, symptom | Lim et al., 2010 |

| PsbO | Surrounding chloroplast | Symptom | Jang et al., 2013 | ||

| Bamboo mosaic virus (BaMV) | RNA 3′ UTR | cPGK | Chloroplast Cytoplasm, | Replication | Cheng et al., 2013 |

| Potato virus X (PVX) | CP | Plastocyanin | Chloroplast | Symptom | Qiao et al., 2009 |

| Alfamovirus/Bromoviridae | |||||

| Alfalfa mosaic virus (AMV) | CP | PsbP | Cytoplasm | Replication | Balasubramaniam et al., 2014 |

| Cucumovirus/Bromoviridae | |||||

| Cucumber mosaic virus (CMV) | 1a, 2a | Tsip1 | Cytoplasm | Replication | Huh et al., 2011 |

| Cucumber mosaic virus Y strain satellite RNA (CMV-Y-sat) | 22-nt vsiRNA** | ChlI mRNA | Cytoplasm | Symptom | Shimura et al., 2011; Smith et al., 2011 |

| Potyvirus/Potyviridae | |||||

| Potato virus Y (PVY) | CP | RbCL | – | Symptom | Feki et al., 2005 |

| HC-Pro | MinD | Cytoplasm | Symptom | Jin et al., 2007 | |

| CF1β | Chloroplast | Symptom | |||

| Onion yellow dwarf virus (OYDV) | P3 | RbCL, RbCS | – | – | Lin et al., 2011 |

| Plum pox virus (PPV) | CI | PsaK | – | Host defense | Jimenez et al., 2006 |

| Sugarcane mosaic virus (SCMV) | HC-Pro | Fd V | Cytoplasm | Symptom | Cheng et al., 2008 |

| Soybean mosaic virus (SMV) | P1 | Rieske Fe/S | – | Symptom | Shi et al., 2007 |

| P3 | RbCL, RbCS | – | – | Lin et al., 2011 | |

| Shallot yellow stripe virus (SYSV) | P3 | RbCL, RbCS | – | – | Lin et al., 2011 |

| Turnip mosaic virus (TuMV) | CP | 37-kD protein | – | – | McClintock et al., 1998 |

| P3 | RbCL, RbCS | – | – | Lin et al., 2011 | |

| Tobacco vein-mottling virus (TVMV) | CI | PsaK | – | Host defense | Jimenez et al., 2006 |

| Dianthovirus/Tombusviridae | |||||

| Red clover necrotic mosaic virus (RCNMV) | MP | GAPDH-A | Chloroplast, Endoplasmic reticulum | Cell-to-cell movement | Kaido et al., 2014 |

| Pomovirus/Virgaviridae | |||||

| Potato mop-top virus (PMTV) | TGB2 | Chloroplast lipid | Chloroplast | Replication | Cowan et al., 2012 |

| Tobamovirus/Virgaviridae | |||||

| Tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) | 126 K replicase | PsbO | – | Host defense | Abbink et al., 2002 |

| NRIP | Cytoplasm, Nucleus | Host defense | Caplan et al., 2008 | ||

| 126 K/183 K replicase | AtpC | VRCs | Host defense | Bhat et al., 2013 | |

| RCA | VRCs | Host defense | |||

| MP | RbCS | Cytoplasm | Cell-to-cell movement | Zhao et al., 2013 | |

| Tomato mosaic virus (ToMV) | CP | Fd I | Cytoplasm | Symptom | Sun et al., 2013; Ma et al., 2008 |

| IP-L | Thylakoid membrane | Long distance movement | Li et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2008 | ||

| MP | RbCS | Cytoplasm | Cell-to-cell movement | Zhao et al., 2013 | |

| ssRNA NEGATIVE SENSE VIRUSES | |||||

| Tenuivirus/Unassigned | |||||

| Rice stripe virus (RSV) | SP | PsbP | Cytoplasm | Symptom | Kong et al., 2014 |

| ssDNA VIRUSES | |||||

| Begomovirus/Geminiviridae | |||||

| Abutilon mosaic virus (AbMV) | MP | cpHSC70-1 | Cell periphery, Chloroplast | Cell-to-cell movement | Krenz et al., 2010, 2012 |

| dsDNA VIRUSES | |||||

| Caulimovirus/Caulimoviridae | |||||

| Cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) | P6 | CHUP1 | VRCs | Cell-to-cell movement | Angel et al., 2013 |

Virus taxonomy is in format of Genus/Family.

Virus-derived small interfering RNA.

– Not addressed. ssRNA, single-stranded RNA; ssDNA, single-stranded DNA.

In this review, we focus on the topic of how chloroplast factors and viral components interact with each other and how these interactions contribute to viral pathogenesis and symptom development, especially in virus-susceptible hosts.

Chloroplast is involved in viral symptom production

Although the development of viral symptoms can be traced back to different causes, the disruption of normal chloroplast function has been suggested to cause typical photosynthesis-related symptoms, such as chlorosis and mosaic (Rahoutei et al., 2000). Chloroplast has been implicated as a common target of plant viruses for a long time. For instance, the severe chlorosis on systemic leaves infected by CMV in Nicotiana tabacum cv. Xanthi nc is associated with size-reduced chloroplasts containing fewer grana (Roberts and Wood, 1982). A second example shows that the leaf mosaic pattern caused by virus infection can be due to the layout of clustered mesophyll cells in which chloroplasts were damaged to various degrees (Almási et al., 2001). A third example shows that symptom caused by PVY infection is often associated with decrease in the number and size of host plant chloroplasts as well as inhibited photosynthesis (Pompe-Novak et al., 2001). Based on the current studies, the ultrastructural alteration of chloroplast and the reduced abundance of proteins involved in photosynthesis are the two main causes of virus induced chloroplast symptomatology (see below).

Effect of virus infection on chloroplast structure

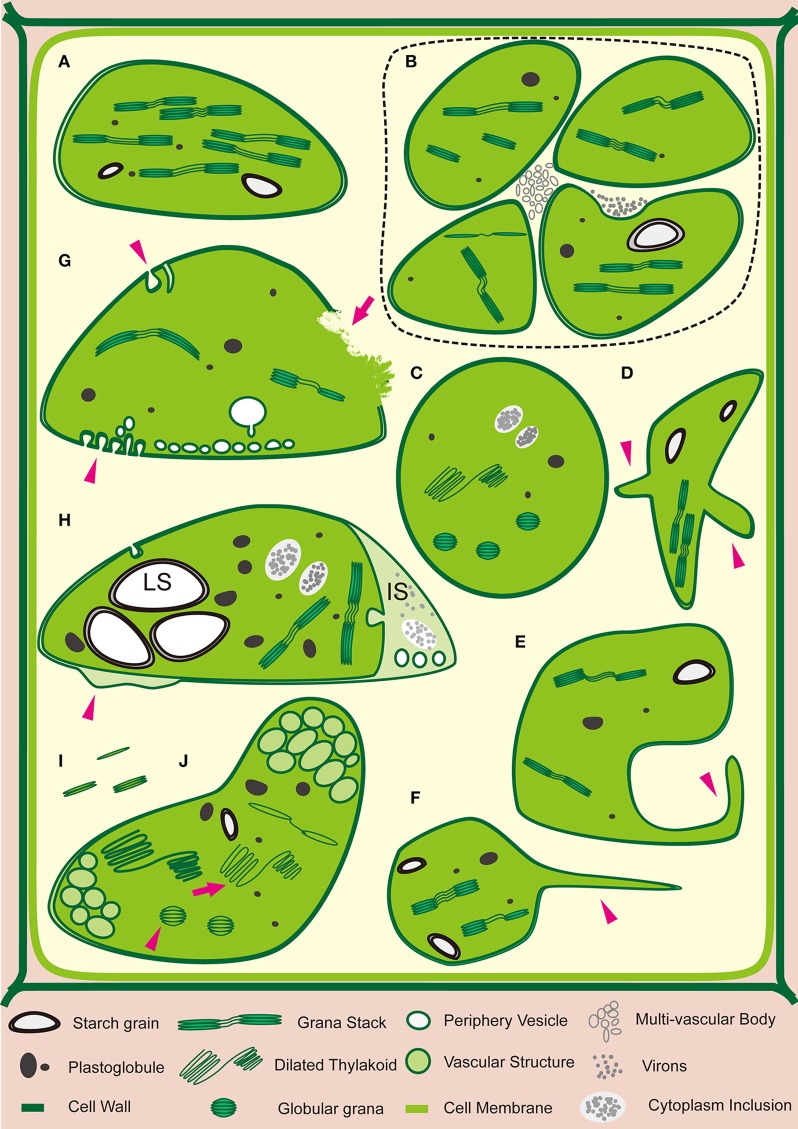

Successions of analysis on the ultrastructural organization of plant cells infected with viruses have been performed with electron microscopy since the 1940s. There is a stunning convergence among different host-virus systems where significant alteration or rearrangement of the chloroplast ultrastructure is correlated with the symptom development (Bald, 1948; Arnott et al., 1969; Ushiyama and Matthews, 1970; Allen, 1972; Liu and Boyle, 1972; Mohamed, 1973; Moline, 1973; Appiano et al., 1978; Tomlinson and Webb, 1978; Schuchalter-Eicke and Jeske, 1983; Bassi et al., 1985; Choi, 1996; Mahgoub et al., 1997; Xu and Feng, 1998; Musetti et al., 2002; Zechmann et al., 2003; Guo et al., 2004; El Fattah et al., 2005; Schnablová et al., 2005; Li et al., 2006; Yan et al., 2008; Laliberté and Sanfaçon, 2010; Montasser and Al-Ajmy, 2015; Zarzyńska-Nowak et al., 2015; Zhao et al., 2016). The chloroplast malformations include (1) overall decrease of chloroplast numbers and chloroplast clustering; (2) atypical appearance of chloroplast, such as swollen or globule chloroplast, chloroplast with membrane-bound extrusions or amoeboid-shaped chloroplast, generation of stromule (a type of dynamic tubular extensions from chloroplast); (3) irregular out-membrane structures such as peripheral vesicle, cytoplasmic invagination, membrane proliferations and broken envelope; (4) changes of content inside the chloroplast such as small vesicles or vacuoles in stroma, large inter-membranous sac, numerous, and/or enlarged starch grains, increase in the number and size of electron-dense granules/plastoglobules/bodies; (5) unusual photosynthetic structures such as disappearance of grana stacks, distorted, loosen, or dilated thylakoid and the disappearance of stroma; and (6) completely destroyed chloroplasts and disorganized grana scattering into the cytoplasm. In these studies, the viruses are from 12 families and have either sense ssRNA, antisense ssRNA or ssDNA genomes, covering the majority of genera and including those responsible for devastating disease. This implies that chloroplast abnormality is a common event across diverse plant-virus interactions. The types of chloroplast abnormalities caused by virus infection are summarized in Table 2 and schemed in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Structural changes of chloroplasts induced by virus infection.

| Plant Virus* | Chloroplast Abnormality | Plant Host | Virus Factor | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ssRNA POSITIVE-STRAND VIRUSES | ||||

| Potexvirus/Alphaflexiviridae | ||||

| Potato virus X (PVX) | Invaginations of cytoplasm into chloroplast | Datura stramonium, Solanum tuberosum | Virus particle, Virus inclusion | Kozar and Sheludko, 1969 |

| Dilated granal lamella, enlarged stromal areas, thylakoid vesicles | Nicotiana benthamiana | CP | Qiao et al., 2009 | |

| Alternanthera mosaic virus (AltMV) | Vesicular invaginations | Nicotiana benthamiana | Viral RNA, TGB3 | Lim et al., 2010 |

| Carlavirus/Betaflexiviridae | ||||

| Potato virus S (PVS) | Cytoplasm invagination | Chenopodium quinoa | Virion | Garg and Hegde, 2000 |

| Cucumovirus/Bromoviridae | ||||

| Cucumber mosaic virus isolate 16 (CMV-16) | Reduction in chloroplast number and size, completely destroyed chloroplasts and disorganized grana scattering into the cytoplasm | Lycopersicon esculentum | – | Montasser and Al-Ajmy, 2015 |

| CMV P6 strain (CMV-P6) | Tiny chloroplast with fewer grana, myelin-like chloroplast-related structures | Nicotiana tabacum | – | Roberts and Wood, 1982 |

| CMV Malaysian isolate | Disorganized thylakoid system, crystallization of phytoferritin macro molecules and, large starch grains | Catharanthus roseus | – | Mazidah et al., 2012 |

| CMV pepo strain with CP129 substitutions | Few thylakoid membranes, no granum stacks, abnormal-shaped and hyper-accumulated starch grains | Nicotiana tabacum | – | Mochizuki and Ohki, 2011 |

| CMV pepo strain VSR deficient mutant with CP129 substitutions | Fewer thylakoid membranes and granum stacks | Nicotiana tabacum | – | Mochizuki et al., 2014b |

| Polerovirus/Luteoviridae | ||||

| Beet western yellows virus (BWYV) | Disappearance of grana stacks, stroma lamellae, large starch grains, osmiophilic granules | Lactuca sativa, Claytonia perfoliata | – | Tomlinson and Webb, 1978 |

| Sugarcane Yellow Leaf Virus (ScYLV) | Swollen chloroplast, rectangular grana stacks, more plastoglobules | Saccharum spec. | – | Yan et al., 2008 |

| Potyvirus/Potyviridae | ||||

| Bean yellow mosaic virus (BYMV) | Increased stromal area, swollen chloroplast, loss of envelopes, dilated thylakoids, decreased chloroplast number | Vicia faba | – | Radwan et al., 2008 |

| Maize dwarf mosaic virus strain A (MDMV-A) | Small vesicles, deformation of membranes, reduction in grana stack height, disappearance of osmiophilic globules, degeneration of structures | Sorghum bicolor | – | Choi, 1996 |

| MDMV Shandong isolate (MDMV-SD) | Thylakoid swelling, envelope broking | Zea mays | – | Guo et al., 2004 |

| Plum pox virus (PPV) | Dilated thylakoid, increase in the number and size of plastoglobuli, decreased amount of starch in chloroplasts from palisade parenchyma | Prunus persica L. | – | Hernández et al., 2006 |

| Dilated thylakoids, increased number of plastoglobuli, peculiar membrane configurations | Pisum sativum | – | Díaz-Vivancos et al., 2008 | |

| Lower amount of starch granules, disorganized grana structure | Prunus persica L. | – | Clemente-Moreno et al., 2013 | |

| Potato virus Y (PVY) | Reduced chloroplast number, smaller chloroplasts with exvaginations | Solarium tuberosum | – | Pompe-Novak et al., 2001 |

| Decrease of volume density of starch, increase of volume density of plastoglobuli | Nicotiana tabacum | – | Schnablová et al., 2005 | |

| Sugarcane mosaic virus (SCMV) | Swollen chloroplast, increased number of plastoglobuli | Sorghum bicolor | – | El Fattah et al., 2005 |

| Turnip mosaic Virus (TuMV) | Chloroplast aggregation, irregular shaped chloroplast, large osmiophilic granules, poorly developed lamellar system, few or no starch grains, | Chenopodium quinoa | Virus particle | Kitajima and Costa, 1973 |

| Zucchini yellow mosaic virus (ZYMV) | Decrease of chloroplasts amount, decreased thylakoids, increased plasto-globule and starch grain in chloroplast | Cucurbita pepo | – | Zechmann et al., 2003 |

| Fijivirus/Reoviridae | ||||

| Maize rough dwarf virus (MRDV) | Membrane disappearance, swollen grana discs, periphery vesicles | Zea mays | Virus particle | Gerola and Bassi, 1966 |

| Distorted grana and paired membranes. | Chenopodium quinoa | Virus particle | Martelli and Russo, 1973 | |

| Fabavirus/Secoviridae | ||||

| Broad bean wilt virus 2 (BBWV-2) isolate B935 | Inhibited lamellar development, membrane vesiculation | Vicia faba | – | Li et al., 2006 |

| BBWV-2 isolate PV131 | Chloroplast with swollen or disintegrated membrane | Vicia faba | – | |

| Tombusvirus/Tombusviridae | ||||

| Artichoke mottled crinkle virus (AMCV) | Distorted grana and paired membranes. | Chenopodium quinoa | Virus particle | Martelli and Russo, 1973 |

| Tomato bushy stunt virus (TBSV) | Large plastidial vacuole, disorganized lamellar system, multivesicular bodies originate from chloroplasts, chloroplasts clustered around a group of multivesicular bodies | Gomphrena globosa | Virus particle | Appiano et al., 1978 |

| Large inter-membranous sac, rearrangement of the thylakoids | Datura stramonium | – | Bassi et al., 1985 | |

| Unassigned/Tombusviridae | ||||

| Maize necrotic streak virus (MNeSV) | Chloroplast swollen, out membrane invagination | Zea mays | – | De Stradis et al., 2005 |

| Tymovirus/Tymoviridae | ||||

| Melon rugose mosaic virus (MRMV) | Peripheral vesicles, tendency to aggregate | Cucumis melo | – | Mahgoub et al., 1997 |

| Turnip yellow mosaic virus (TYMV) | Peripheral vesicles, reduction of grana number, chlorophyll content; increases in amounts of phytoferritin and numbers of osmiophilic globules | Brassica rapa | Viron, Viral RNA | Ushiyama and Matthews, 1970; Hatta and Matthews, 1974 |

| Belladonna mottle virus physalis mottle strain (BeMV-PMV) | Vesicles develop in chloroplasts, vesiculations of the outer membranes | Datura stramonium | Viron | Moline, 1973 |

| Wild cucumber mosaic virus (WCMV) | Double membrane vesicles in chloroplasts, single membrane vesicles surrounding chloroplasts | Marah oreganus | Virus particle | Allen, 1972 |

| Hordeivirus/Virgaviridae | ||||

| Barley stripe mosaic virus (BSMV) | Surrounded chloroplasts, cytoplasmic invaginations into chloroplasts, aggregated chloroplasts, rearrangement of the thylakoids, electron transparent vacuoles in stroma | Hordeum vulgare | Viron | Carroll, 1970; Zarzyńska-Nowak et al., 2015 |

| Peripheral vesicles; Type1: elongated grana or anastomosed lamellae, composed of pellucid stroma, twisted or convoluted membranes forming tubular networks; Type2: swollen and contained disarranged internal membranes; Type3: electron dense stroma, cytoplasmic invaginations. | Datura stramonium | Genomic ssRNA | McMullen et al., 1978 | |

| Rounded and clustered chloroplasts, cytoplasmic invaginations and inclusions at the periphery | Nicotiana benthamiana | TGB2, CP, γb, virus-like particle | Torrance et al., 2006 | |

| Pomovirus/Virgaviridae | ||||

| Potato mop-top virus (PMTV) | Large starch grains, large cytoplasmic inclusion, terminal extension, | Nicotianabenthamiana | Genomic RNA, CP, TGB2 | Cowan et al., 2012 |

| Tobamovirus/Virgaviridae | ||||

| Ribgrass mosaic virus (RMV) | Disappearance of stroma, decrease in grana lamella, Large starch grains, osmiophilic granules | Nicotiana tabacum | – | Xu and Feng, 1998 |

| Tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) | Aggregates and vecuoles in chloroplast | Lycopersicon esculentum | Shalla, 1964 | |

| Enlarged plastids, supergranal thylakoids, large accumulations of osmiophilic bodies | Lycopersicon esculentum | – | Arnott et al., 1969 | |

| Disappearance of stroma, decrease in grana lamella, large starch grains, osmiophilic granules | Nicotiana tabacum | CP | Xu and Feng, 1998 | |

| Swelling, more osmophilic plastoglobuli, loosened thylakoid structure | Capsicuum anuum | – | Mel'nichuk et al., 2002 | |

| TMV U5 strain | Peripheral vesicles | Nicotiana tabacum | Virus particle | Betto et al., 1972 |

| TMV yellow strain | Filled with osmiophilic globules, rearranged, swollen or eliminated lamellar system, extensive chloroplast degradation | Solanum tuberosum | – | Liu and Boyle, 1972 |

| TMV flavum strain (TMV-Flavum) | Swollen or globular chloroplast, distorted thylakoid membranes, grana depletion, unidentified granular matter | Nicotiana tabacum | MP, CP | Lehto et al., 2003 |

| Tomato mosaic Virus (ToMV) | Slightly swollen and distorted cholroplast, large starch grains | Nicotiana tabacum | Virus particle | Ohnishi et al., 2009 |

| ToMV L11Y strain (ToMV-L11Y) | Flaccid chloroplast, reduced thylakoid stacks and enlarged spaces between the stacks, cytoplasm penetrates into chloroplast, tubular complexes | Nicotiana tabacum | – | Ohnishi et al., 2009 |

| ssRNA NEGATIVE STRAND VIRUSES | ||||

| Tospovirus/Bunyaviridae | ||||

| Tomato spotted wilt virus (TSWV) | Peripheral vesicles | Nicotiana tabacum | – | Mohamed, 1973 |

| Tenuivirus/Unassigned | ||||

| Rice stripe virus (RSV) | Reduced sheets of grana stacks, increased amount and size of starch granules | Oryza Sativa | Virus particle | Zhao et al., 2016 |

| Membrane proliferations | Nicotiana benthamiana | NSvc4 | ||

| ssDNA VIRUSES | ||||

| Begomovirus/Geminiviridae | ||||

| Abutilon Mosaic Virus (AbMV) | Disorganization of thylakoid system, grana-stroma elimination | Abutilon spec | – | Schuchalter-Eicke and Jeske, 1983 |

| Degenerated thylakoids, more plastoglobuli, less starch, and accumulation of amorphous electron-dense material | Abutilon selovianum | Genomic DNA | Gröning et al., 1987 | |

| Generation of stromules | Nicotiana benthamiana | MP | Krenz et al., 2012 | |

Virus taxonomy is in format of Genus/Family.

– Not addressed. ssRNA, single-stranded RNA; ssDNA, single-stranded DNA.

Figure 1.

Changes in the Ultrastructure of Chloroplasts Induced by Virus Infection. (A) Normal chloroplast. (B) Aggregated chloroplasts (surrounded with dotted line). (C) Swollen chloroplast. (D) Chloroplast with membrane-bound extrusions. Arrow heads indicate membrane extrusions. (E) Amoeboid-shaped chloroplast, arrow head indicates chloroplast membrane extrusions. (F) Chloroplast with stromule, arrow head indicates the stromule. (G) Chloroplast with irregular out-membrane structures such as peripheral vesicle, cytoplasmic invagination, membrane proliferations and broken envelope. Arrow heads indicates cytoplasmic invaginations, arrow indicates broken envelope of chloroplast. (H) Chloroplast with abnormal content changes such as small vesicles, membrane proliferations (arrow head) and inter-membranous sac (IS), large starch grain (LS) and exaggeration of plastoglobules. (I) Disorganized grana scattering into the cytoplasm. (J) Chloroplast with unusual photosynthetic structures such as dilated thylakoid (arrow) and globular grana (arrow head) and vascular structures.

Viral effectors are related to the chloroplast structural changes

Recent reports have revealed that viral factors, especially coat proteins (CPs), affect chloroplast ultrastructure and symptom development (see below).

Viral coat proteins (CPs) have been demonstrated as determinants of symptom phenotypes for a much long period (Heaton et al., 1991; Neeleman et al., 1991). The earlier research showed that virion-like particles or virus inclusion in chloroplast are positively related to the development of mosaic symptom caused by TMV (Bald, 1948; Shalla, 1964). The more virion-like particles accumulated in chloroplast, the more severe morphological defects of chloroplast structure occurred (Matsushita, 1965; Shalla, 1968; Granett and Shalla, 1970; Betto et al., 1972). Later researches indicate that virion-like particles in chloroplast are pseudovirions, in which chloroplast transcripts are encapsidated by TMV CPs (Shalla et al., 1975; Rochon and Siegel, 1984; Atreya and Siegel, 1989), highlighting the involvement of CPs in the alteration of chloroplast ultrastructure. TMV CP does not possess a classical chloroplast transit peptide (TP) but can be imported into chloroplast effectively in a ATP-independent mode (Banerjee and Zaitlin, 1992). The majority of TMV CPs in chloroplasts are associated with the thylakoid membranes in systemically invaded N. tabacum leaves (Reinero and Beachy, 1986; Hodgson et al., 1989). Various natural TMV mutants, whose CPs excessively accumulate in chloroplast, always induce more severe symptoms and aggravated inhibition of the PS II activity (Regenmortel and Fraenkel-Conrat, 1986; Reinero and Beachy, 1986, 1989; Banerjee et al., 1995; Lehto et al., 2003), suggesting that chloroplast-targeted CPs act as the inducer of chloroplast ultrastructure rearrangements (Figure 1, Table 2). Tobamovirus CP can bind tobacco chloroplast Ferredoxin I (Fd I) (Sun et al., 2013, Table 1), while TMV infection reduces the protein level of Fd I in tobacco leaves (Ma et al., 2008). Silencing of Fd1 in tobacco plants leads to symptomatic chlorosis phenotype and enhances CP accumulation in chloroplast as well as virus multiplication, suggesting that the CP-Fd I interaction may contribute to the development of chlorosis and mosaic symptoms.

PVX CP and viral particles can also be detected in chloroplast of the infected plants, causing structural alteration of chloroplast membranes and grana stacks (Kozar and Sheludko, 1969; Qiao et al., 2009). PVX CP interacts with the chloroplast TP of plastocyanin (Table 1), and silencing of plastocyanin in N. benthamiana reduces viral symptom severity. In plastocyanin silenced plants, the accumulation of CP in chloroplasts was also reduced although total CP amount in infected cells did not change (Qiao et al., 2009), suggesting that the CP-plastocyanin interaction positively contributes to viral symptom-associated chloroplast abnormality (Figure 1, Table 2).

PVY CP is preferentially associated with the thylakoid membranes (Gunasinghe and Berger, 1991). PVY CP interacts with the large subunits of RuBisCO (RbCL) (Table 1) and this interaction may be involved in the production of mosaic and chlorosis symptoms (Feki et al., 2005). Further research indicates that chloroplast-targeted, but not cytosol-localized CP induces virus-like symptom (Naderi and Berger, 1997a,b). These observations suggest an intimate relationship between chloroplasts and PVY CP during the process of inhibiting PS II in viral pathogenesis.

CMV infection causes symptoms associated with chloroplast ultrastructure changes (Roberts and Wood, 1982; Shintaku et al., 1992; Mazidah et al., 2012). CMV CP can be transported into intact chloroplast promptly in a ATP-independent mode and the amount of CP into chloroplast correlated with the severity of mosaic symptoms (Liang et al., 1998). The single amino acid substitution at residue 129 in CP of CMV pepo strain is found to induce chloroplast abnormalities (Figure 1, Table 2) associated with the alteration of chlorosis severity (Shintaku et al., 1992; Suzuki et al., 1995; Mochizuki and Ohki, 2011; Mochizuki et al., 2014b), suggesting that CMV CP alone possess the virulence to induce chlorosis and chloroplast abnormalities in CMV-infected tobacco plants (Mochizuki and Ohki, 2011; Mochizuki et al., 2014b).

Viral CPs could also impose virulent effects from outside of the chloroplasts. A series of CP deletion mutants of TMV (Lindbeck et al., 1991) and ToMV spontaneous mutant ToMV-L11Y (Ohnishi et al., 2009) causes severe chlorosis associated with severe deformation and disruption of chloroplasts and the mutant CPs are shown to contribute to this severe chlorosis (Lindbeck et al., 1991; Ohnishi et al., 2009). Because the mutant CPs aggregate outside of chloroplasts, they may subvert the chloroplast development and cause the degradation of chloroplasts by interfering with the synthesis and transport of CPRPs (Lindbeck et al., 1991, 1992; Ohnishi et al., 2009).

Besides CPs, other viral components are also able to cause chloroplast malformation and contribute to symptom. For example, transgenic expression of CaMV transactivator/viroplasmin (Tav) protein in tobacco plants results in a virus-like chlorosis symptom associated with the abnormal thylakoid stacks (Figure 1, Table 2) and reduces expression of CPRGs (Waliullah et al., 2014). The potexvirus AltMV TGB3, different from its counterpart PVX TGB3, has a chloroplast-targeting signal and preferentially accumulates around the chloroplast membrane (Lim et al., 2010). Overexpression of AltMV TGB3 causes vesiculation at the chloroplast membrane (Figure 1, Table 2) and veinal necrosis symptom (Lim et al., 2010; Jang et al., 2013). AltMV TGB3 strongly interacts with PS II oxygen-evolving complex protein PsbO and this interaction is believed to have a crucial role in viral symptom development and chloroplast disruption (Jang et al., 2013). In PVY-infected cells, viral multifunctional protein HC-Pro may contribute to the change in the number and size of chloroplast by interfering with the normal activity of the chloroplast division-related factor MinD through direct protein interaction (Jin et al., 2007, Table 1). The tenuivirus RSV NSvc4 protein functions as an intercellular movement protein and is localized to PD as well as chloroplast in infected cells. Over-expression of NSvc4 exacerbated malformations of chloroplast (Figure 1, Table 2) and disease symptoms. Interestingly, the chloroplast localization of NSvc4 is dispensable for the symptom determination while the NSvc4 transmembrane domain probably affects the chloroplast from outside (Xu and Zhou, 2012).

Effect of virus infection on expression of chloroplast-targeted proteins

Studies on the effect of virus infection on expression of chloroplast proteins at the transcriptomic and proteomic levels provide insights into the molecular events during symptom expression. In the susceptible plant response to virus infection, the majority of significantly changed proteins are identified to be located in chloroplasts or associated with chloroplast membranes. Most of them are down-regulated and correlate with the severity of chlorosis (Dardick, 2007; Shimizu et al., 2007; Lu et al., 2012; Rodríguez et al., 2012; Kundu et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2013; Mochizuki et al., 2014a). During virus infection, CPRPs represent the most common viral targets. Among them, the light harvesting antenna complex (Naidu et al., 1984a,b, 1986; Liu et al., 2014) and the oxygen evolving complex (OEC) (Takahashi et al., 1991; Takahashi and Ehara, 1992; Pérez-Bueno et al., 2004; Sui et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2015) of PS II are in thylakoid, while RbCS and RubisCO activase (RCA, an AAA-ATPase family protein) are in chloroplast stroma (Díaz-Vivancos et al., 2008; Pineda et al., 2010; Moshe et al., 2012; Kundu et al., 2013).

As the biosynthesis of CPRPs is a complicated process with a series of steps (Seidler, 1996), plant virus can affect CPRPs at varied levels including transcription, post-transcription, translation, transportation into the chloroplast, assembly and degradation in chloroplast, to contribute to symptom development (Lehto et al., 2003; Pérez-Bueno et al., 2004).

Several plant viruses perturb CPRPs expression at transcription level either in chloroplast or via retrograde signaling into nucleus. Infection of TMV flavum strain leads to a total depletion of PS II core complex and OEC, including chloroplast-encoded CPRP PsbA and nuclear-encoded CPRPs LhcB1, LhcB2 (light-harvesting chlorophyll a/b-binding protein B1, B2) and PsbO. However, the PsbA mRNA accumulated to a higher level in the infected leaves (Lehto et al., 2003). Thus, TMV flavum may block PsbA translation via reducing the level of chloroplast ribosomal RNA (Fraser, 1969) and inhibit the transcription of nuclear-encoded CPRGs through feed-back signaling (Lehto et al., 2003). Similarly, in the case of CMV pepo strain and its CP129 mutant isolates, the down-regulation patterns of transcription levels of different CPRGs correlated with the amino acid substitution in the CP protein of the relative isolates, where CMV CP probably repress the transcription of CPRGs via the retrograde signaling from chloroplast into nucleus (Mochizuki et al., 2014a).

It is interesting that plant virus can also exploit host RNA silencing machinery to manipulate CPRGs at post-transcription level. The enlightening evidence is illustrated by CMV-Y satellite (CMV-Y-sat) RNA which can disturb chloroplast function and induce disease symptoms (Shimura et al., 2011; Smith et al., 2011). A 22-nt siRNA derived from CMV-Y-sat RNA targets the magnesium protoporphyrin chelatase subunit I (ChlI) gene transcripts and down-regulates its expression by RNA silencing (Table 1), which leads to a more sever symptom characterized as bright yellow mosaic (Takanami, 1981; Shimura et al., 2011; Smith et al., 2011). In addition, infection by viroids (small non-protein-coding RNAs) results in the production of viroid-derived small RNAs (vd-sRNAs) (Papaefthimiou et al., 2001; Martínez de Alba et al., 2002). Peach latent mosaic viroid (PLMVd) belongs to family Avsunviroidae whose members replicate in chloroplast, and may elicit an albino-variegated phenotype (peach calico, PC) with blocked chloroplast development and depletion of chloroplast-encoded proteins (Rodio et al., 2007). The PLMVd variants associated with PC contain an insertion of 12–14 nt that folds into a hairpin with a U-rich tetraloop, the sequence of which is critical for inciting the albino phenotype. Actually, vd-sRNAs from the hairpin insertion induce cleavage of the mRNA encoding the CPRP chloroplastic heat-shock protein 90 (cHSP90) as predicted by RNA silencing, eventually resulting in PC symptoms (Navarro et al., 2012).

In addition to the virus-derived small RNAs, plant viruses may also modify host microRNA (miRNA) pathway for targeting CPRGs transcripts. The tenuivirus RSV, causing a devastating disease in East Asia countries, hijacks CPRP during infection and perturbs photosynthesis (Satoh et al., 2010; Shi et al., 2016). The perturbation of photosynthesis by RSV is probably caused by up-regulating a special miRNA that targets key genes in chloroplast zeaxanthin cycle, which impairs chloroplast structure and function (Yang et al., 2016).

Viral factors may reduce the level of CPRPs by direct association with target proteins. Tobamoviruses CPs particularly associate with the PS II complex and reduce the levels of PsbP and PsbQ (Hodgson et al., 1989; Pérez-Bueno et al., 2004; Sui et al., 2006). PVY HC-Pro can reduce the amount of ATP synthase complex by interaction with the NtCF1β-subunit in both the PVY-infected (Table 1) and the HC-Pro transgenic tobacco plants, leading to a decreased photosynthetic rate (Tu et al., 2015). Potyviruses TuMV, SMV, SYSV, and OYDV may hijack RbCS and/or RbCL via the interaction with P3 or P3N-PIPO during infection to perturb photosynthetic activity (Lin et al., 2011). Potyvirus SCMV infection significantly down-regulates mRNA level of photosynthetic Fd V rather than that of the other isoproteins (Fd I and Fd II) in maize, while SCMV HC-Pro specifically interacts with the chloroplast precursor of Fd V via TP in cytoplasm outside the chloroplasts (Table 1), suggesting that SCMV HC-Pro perturbs the importing of Fd V into chloroplasts and leads to structure and function disturbance of chloroplast (Cheng et al., 2008). Potyvirus SMV P1 (a serine protease) strongly interacts with host plant-derived, but only weakly with non-host Arabidopsis-derived, Rieske Fe/S protein of cytochrome b6/f complex, an indispensable component of the photosynthetic electron transport chain in chloroplasts (Table 1), suggesting that SMV P1-Rieske Fe/S protein interaction is involved in symptom development (Shi et al., 2007). RSV disease specific protein (SP) is a symptom determinant protein and its overexpression enhances RSV symptom (Kong et al., 2014). During RSV infection, accumulation of SP is associated with alteration in structure and function of chloroplast. SP interacts with 23-kD OEC PsbP, and relocates PsbP from chloroplast into cytoplasm (Table 1), while silencing of PsbP enhances disease symptom severity and virus accumulation (Kong et al., 2014).

Chloroplast is involved in the process of the plant virus life cycle

Increasing studies have unraveled that chloroplast constituents participate in different stages during virus infection. For example, chloroplast is reported to be associated with viral uncoating, an important step of replication (Xiang et al., 2006). Tombusvirus CNV CP harbors an arm region of 38 amino acids that functions as a chloroplast TP to direct CP import to the chloroplast stroma, which is critical for viral disassembly. CNV CP mutant deficient in exposure of the arm region is inefficient to establish infection, highlighting the crucial role of chloroplast targeting in CNV uncoating (Xiang et al., 2006).

Chloroplast and its factors participate in virus replication

Chloroplast affords compartment and membrane contents for the replication of plant viruses and probably helps them to evade the RNA-mediated defense response (Ahlquist et al., 2003; Dreher, 2004; Torrance et al., 2006). Plant viruses propagate via RNA-protein complex named viral replication complexes (VRCs), which are the factory for producing progeny viruses (Más and Beachy, 1998, 2000; Asurmendi et al., 2004). During replication of RNA viruses, double-strand RNA (dsRNA) is generated as an intermediate product. As a response against virus infection, the dsRNA replication intermediates can be detected by the host RNA silencing machinery (Angell and Baulcombe, 1997; Baulcombe, 1999). Correspondingly, plant viruses have evolved some mechanisms by encoding viral suppressor of RNA silencing or by associating replication with host membranes (Ahlquist, 2002; Ahlquist et al., 2003). For a large group of viruses, VRCs are associated with the chloroplast envelope, particularly the peripheral vesicles and cytoplasmic invaginations in chloroplast (Figure 1, Table 2), including alfamovirus AMV (de Graaff et al., 1993), hordeivirus BSMV (Carroll, 1970; Torrance et al., 2006), potyviruses MDMV (Mayhew and Ford, 1974), PPV (Martin et al., 1995), TEV (Gadh and Hari, 1986), TuMV (Kitajima and Costa, 1973), and tymovirus TYMV (Lafleche et al., 1972; Bové and Bové, 1985; Garnier et al., 1986; Lesemann, 1991; Dreher, 2004). The chloroplast membrane associated organization probably helps to shield viral RNAs from recognition by host RNA silencing machinery (Dreher, 2004).

Viral factors, either viral genomic RNAs or proteins, can mediate the chloroplast targeting of VRCs for replication and subsequent virion assembly (Prod'homme et al., 2003; Jakubiec et al., 2004; Torrance et al., 2006). BSMV replicative dsRNA intermediates exist in the chloroplast peripheral vesicles during infection (McMullen et al., 1978; Lin and Langenberg, 1984, 1985; Torrance et al., 2006); in the presence of the viral genome RNA, both TGB2 and γb can be recruited to chloroplasts for virus replication (Torrance et al., 2006). The low pH condition of chloroplast vesicles where TYMV RNA is synthesized is required for the interaction between viral RNA and CP to process virion assembly (Rohozinski and Hancock, 1996). The TYMV VRC-associated membrane vesicles localize at the chloroplast envelope (Prod'homme et al., 2001). TYMV N-terminal replication protein (140 K) is a key organizer of TYMV VRCs assembly and a major determinant for chloroplast localization of TYMV for replication. The 140 K protein can localize to the chloroplast envelope autonomously and interacts with the C-terminal replication protein (66 K) to mediate the targeting of 66 K to the chloroplast envelope (Prod'homme et al., 2003; Jakubiec et al., 2004). TuMV 6 K protein (6 K or 6 K2) can autonomously allocate to chloroplast membrane and promote the adhesion of the adjacent chloroplasts via actomyosin motility system in infected host cells. During the infection, TuMV 6 K induces the formation of 6 K-containing membranous vesicles at endoplasmic reticulum exit sites and sequentially traffic to chloroplast, while the chloroplast-bounded 6 K-vesicles are recruited to VRCs containing viral dsRNA (Wei et al., 2010), supporting the idea that the chloroplast-bound 6 K vesicles are the cellular compartment for TuMV replication. Blocking the fusion of virus-induced vesicles with chloroplasts by the inhibition of SNARE protein Syp71 significantly reduced the viral infection (Wei et al., 2013).

Special chloroplast components are involved in the targeting of VRCs to chloroplast. The lipid in chloroplast membrane can associate with pomovirus PMTV TGB2 (Table 1) and facilitate the viral RNA to localize to chloroplast membranes for replication (Cowan et al., 2012). Furthermore, chloroplast factors also participate in the formation of VRCs. Proteomic analysis suggests that sobemovirus RYMV recruits CPRPs such as Ferredoxin-NADP reductase (FNR), RbCS, RCA, and chaperonin 60 to its VRCs during all the infectious stages including replication, long-distance trafficking and symptoms development (Brizard et al., 2006). The 43 kD CPRP chloroplast phosphoglycerate kinase (cPGK) specifically interacts with 3′-UTR of the potexvirus BaMV genomic RNA (Lin et al., 2007, Table 1). Silencing of Nb-cPGK or mislocalization of cPGK protein reduced BaMV accumulation, suggesting that cPGK may mediate BaMV RNA targeting to chloroplast for replication (Cheng et al., 2013). Interestingly, in Arabidopsis genotype Cvi-0 the natural recessive resistance gene rwm1 against potyvirus WMV encodes a mutated version of cPGK (Ouibrahim et al., 2014), illuminating that the conserved CPRP cPGK may be required for successful replication and infection of a range of plant viruses (Lin et al., 2007; Ouibrahim et al., 2014).

Chloroplast factors participate in viral movement

The intercellular trafficking and systemic spreading of plant virus need movement proteins (MPs) to fulfill the transport via symplastic routes within plant hosts (Wolf et al., 1989; Ding et al., 1992; Imlau et al., 1999; Lazarowitz and Beachy, 1999). To facilitate virus movement, varied MPs possess common features such as nucleic acid binding activity (Citovsky et al., 1990), specific plasmodesmata (PD) localization (Ding et al., 1992; Fujiwara et al., 1993) and the ability to increase the size exclusion limit of PD (Wolf et al., 1989).

Chloroplast and its factors also participate in virus movement. AltMV TGB3 has a chloroplast-targeted signal and accumulates preferentially in mesophyll cells, which is essential for virus movement. Mutation of the chloroplast-targeted signal in AltMV TGB3 impairs virus movement from epidermal into the mesophyll cells as well as viral long-distance traffic (Lim et al., 2010). Geminivirus AbMV MP interacts with chloroplast-targeted 70-kD heat shock protein (cpHSC70-1) and co-localized to chloroplasts (Table 1). Silencing of cpHSC70-1 affects chloroplast stability and causes a substantial reduction of AbMV movement but has no effect on viral DNA accumulation (Krenz et al., 2010, 2012). AbMV can replicate in chloroplast (Gröning et al., 1987, 1990) and induce the biogenesis of stromule network (Figure 1, Table 2). AbMV may use cpHSC70-1 for trafficking along chloroplast stromules into a neighboring cell or from plastids into the nucleus (Krenz et al., 2012).

Viral factors can interact with and hijack chloroplast factors from their normal function and to help viral movement. The CaMV multifunctional P6 protein is the most abundant present in VRCs (Hohn et al., 1997) and associates with PD (Rodriguez et al., 2014). Interestingly, CaMV P6 also interacts with the chloroplast unusual positioning protein1 (CHUP1) (Table 1) that is a thylakoid membrane-associated protein for mediating the routine movement of chloroplast on microfilaments in response to light intensity (Oikawa et al., 2003, 2008). Silencing of CHUP1 slows the formation rate of CaMV local lesion (Angel et al., 2013). Thus, the CaMV P6 protein may mediate the intracellular movement of VRCs to the PD by binding to CHUP1 (Angel et al., 2013). Tobamoviruses ToMV and TMV MPs bind RbCS (Table 1) and the interaction occurs at PD (Zhao et al., 2013). Silencing of RbCS reduced intercellular movement and systemic trafficking of TMV and ToMV (Zhao et al., 2013). Thus, it may be a common strategy for tobamoviruses to hijack RbCS for efficient movement. In addition to MPs, tobamoviruses need their CPs for efficient long distance movement (Wisniewski et al., 1990; Reimann-Philipp and Beachy, 1993; Ryabov et al., 1999). ToMV CP-interacting protein-L (IP-L) is a chloroplast protein (Table 1) and is positively induced by ToMV infection (Zhang et al., 2008). Depletion of IP-L delayed ToMV systemic movement and symptoms (Li et al., 2005). Dianthovirus RCNMV MP interacts with chloroplast protein glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase subunit A (GAPDH-A) (Table 1), while silencing of GAPDH-A inhibits viral MP localization to the cortical VRCs and reduces RCNMV multiplication in the inoculated leaves (Kaido et al., 2014). Therefore, GAPDH-A is relocated from chloroplast to cortical VRCs to facilitate viral cell-to-cell movement during RCNMV infection.

Based on the current studies, it is clear that plant viruses have evolved to utilize abundant chloroplast proteins to regulate their movement.

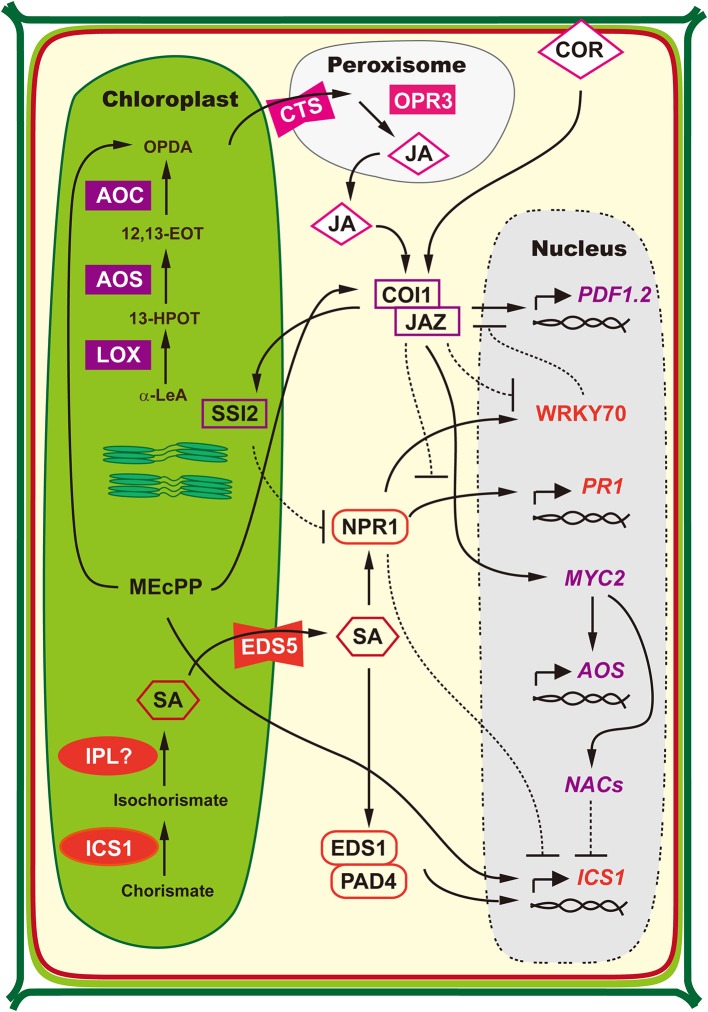

Chloroplasts affect plant defense against viruses

Several hormones regulate plant defense to viruses (Alazem and Lin, 2015). Two of them are salicylic acid (SA) and jasmonic acid (JA). Chloroplast is the crucial site for the biosynthesis of SA (Boatwright and Pajerowska-Mukhtar, 2013; Seyfferth and Tsuda, 2014) and JA (Wasternack, 2007; Schaller and Stintzi, 2009; Wasternack and Hause, 2013). Moreover, chloroplast factors are also involved in the regulation of antagonistic interactions of SA-JA synthesis and signaling (Kunkel and Brooks, 2002; Xiao et al., 2012; Zheng et al., 2012; Lemos et al., 2016). The chloroplast-related regulation of SA and JA biosynthesis is schemed in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Regulation of SA and JA Biosynthesis is Associated with Chloroplast. SA biosynthesis is predominantly accomplished by nucleus-encoded chloroplast-located isochorismate synthase (ICS1). In chloroplasts, ICS catalyzes the conversion of chorismate into isochorismate, which is further converted to SA by undetermined isochorismate pyruvate lyase (IPL). The MATE-transporter ENHANCED DISEASE SUSCEPTIBILITY 5 (EDS5) is responsible for SA transportation from chloroplast into cytosol. Defense-elicited ENHANCED DISEASE SUSCEPTIBILITY 1 (EDS1) and PHYTOALEXIN DEFICIENT 4 (PAD4) complex works in a positive feedback loop to control SA synthesis, which is regulated by SA. While in a negative feedback loop, accumulation of ICS1-produced SA results in the deoligomerization of NON-EXPRESSOR OF PATHOGENESIS-RELATED GENES 1 (NPR1), which is then translocated into nucleus where it suppresses the ICS1 expression (modified from Boatwright and Pajerowska-Mukhtar, 2013; Seyfferth and Tsuda, 2014). JA biosynthesis originates from polyunsaturated fatty acids released from chloroplast membranes. Firstly, α-linolenic acid (18:3) (α-LeA) is catalyzed by lipoxygenase (LOX) to yield the 13-hydroperoxy derivative 13(S)-hydroperoxy-octadecatrienoic acid (13-HPOT). The dehydration of 13-HPOT by allene oxide synthase (AOS) results in the formation of unstable 12, 13(S)-epoxy-octadecatrienoic acid (12,13-EOT), which is the committed step of JA biosynthesis. Then the 12,13-EOT is converted to 12-oxophytodienoic acid (OPDA) by allene oxide cyclase (AOC) through cyclization and concludes the chloroplast-localized part of JA biosynthesis. Subsequently, OPDA is released from chloroplasts and taken up into peroxisomes by transporter COMATOSE (CTS3). The remaining steps are located in peroxisomes and JA is generated through reduction of the cyclopentenone by OPDA reductase 3 (OPR3) and subsequent three cycles of β-oxidation for side-chain shortening. The JA co-receptor complex of CORONATINE INSENSITIVE1 (COI1) and the negative regulator JAZMONATE ZIM DOMAIN (JAZ) proteins regulates the positive feedback loop of JA biosynthesis. Formation of JA subjects JAZ to proteasomal degradation, which allows MYC2 to activate the JA biosynthesis genes such as AOS, AOC, and LOX (modified from Wasternack, 2007; Schaller and Stintzi, 2009; Wasternack and Hause, 2013). NPR1 is the central transcriptional regulator of SA-mediated defense responses and directly regulates PATHOGENESIS-RELATED 1 (PR1) expression (Wang et al., 2006). By wounding or JA treatment, COI1–JAZ co-receptor promotes the degradation of JAZ and release the positively acting transcription factors that binds to JA-responsive promoters to initiate the transcription of JA-responsive genes, such as PLANT DEFENSIN1.2 (PDF1.2) (Chini et al., 2007; Thines et al., 2007; Yan et al., 2009). During the antagonistic interplay between SA and JA, NPR1 suppresses COI1-JAZ mediated induction of JA-responsive genes via WRKY transcription factors, while JA also represses WRKY in COI1-dependent pathway (Li et al., 2004; Gao et al., 2011). On the other hand, the JA signaling proteins, such as chloroplast factor SUPPRESSOR OF SA INSENSITIVITY 2 (SSI2), negatively regulate SA-mediated NPR1-dependent defense responses (Kunkel and Brooks, 2002). Further, the phytotoxin coronatine (COR), a molecular mimic of JA, activates NAC transcription factors via COI1-JAZ and MYC2, which eventually inhibits SA accumulation through repressing ICS1 expression (Zheng et al., 2012). In addition, the stress-induced methylerythritol cyclodiphosphate (MEcPP) acts as a plastid-to-nucleus retrograde signal to increase the transcription level of ICS1 (Xiao et al., 2012). Meanwhile, MEcPP increase the level of JA precursor OPDA and induce JA-responsive genes via a COI1-dependent manner in the presence of high SA (Lemos et al., 2016). Solid lines with arrow head represent activation or promotion, dotted lines with bar head to represent deactivation or inhibition.

SA is a small phenolic compound that plays central roles in plant defense against biotrophic pathogens and is essential for the establishment of local and systemic acquired resistance. The majority of pathogen-induced SA is synthesized via the isochorismate pathway in chloroplasts (Boatwright and Pajerowska-Mukhtar, 2013; Seyfferth and Tsuda, 2014). As a key activator of plant defense response, SA biosynthesis and signaling are activated during incompatible plant-virus interaction (Wildermuth et al., 2001; Garcion et al., 2008). Disruption of SA pathway compromises plant resistance against viruses (Alazem and Lin, 2015). In contrast, the application of SA or its analogs often delays the onset of viral infection and disease establishment by improving plant basal immunity (Radwan et al., 2006, 2007, 2008; Falcioni et al., 2014). A chloroplast-localized protein, named calcium-sensing receptor, is found to act upstream of SA accumulation to link chloroplasts to cytoplasmic-nuclear immune responses (Nomura et al., 2012).

JA is an oxylipin, or oxygenated fatty acid and is synthesized from linolenic acid by the octadecanoid pathway, whose biosynthesis starts with the conversion of linolenic acid to 12-oxo-phytodienoic acid (OPDA) in the chloroplast membranes (Turner et al., 2002). JA is thought to play a positive defense role in compatible plant-virus interactions (Alazem and Lin, 2015). For example, silencing of Coronatine insensitive 1 (COI1), a gene involved in the JA signaling pathway, accelerates the development of symptoms caused by co-infection of PVX and PVY, and accumulation of viral titers at early stages of infection (García-Marcos et al., 2013).

The chloroplasts are major sites of the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and the photosynthetic electron transport chain is responsible for ROS generation (Asada, 2006; Muhlenbock et al., 2008). Superoxide anion () is the primary reduced product of O2 photoreduction and its disproportionation produces H2O2 in chloroplast thylakoids (Asada, 2006; Muhlenbock et al., 2008). The burst of intracellular ROS can be detected during virus infection in both incompatible and compatible interactions (Allan et al., 2001; Hakmaoui et al., 2012). Chloroplast-sourced ROS are essential for hypersensitive response (HR) induced by incompatible defensive response (Torres et al., 2006; Zurbriggen et al., 2010).

The stromules could function to facilitate the magnification and transport of defensive signals into the nucleus. Interestingly, the stromules can be induced during N-mediated TMV resistance response. Further, a number of stromules surround nuclei during plant defense response, which is correlated with the accumulation of chloroplast-localized defense protein NRIP1 and H2O2 in the nucleus. In the absence of virus infection, suppression of chloroplast CHUP1 induces stromules and enhances programmed cell death constitutively (Caplan et al., 2015; Gu and Dong, 2015). In addition, the ultrastructural changes in chloroplast can also be a part of resistant response. For examples, during the hypersensitive reaction of N-mediated TMV resistance, the chloroplasts swelled and the membrane burst before tonoplast ruptured (da Graça and Martin, 1975). During the course of lesion development caused by the nepovirus TRSV, the changes in chloroplast ultrastructure (rounding of chloroplasts) enlighten that chloroplast disturbance could reflect plant-virus incompatible responses (White and Sehgal, 1993). The ultrastructure aberrations of chloroplast represent the intensity of apoptotic processes in PVYNTN infection (Pompe-Novak et al., 2001). Thus, the malformation of chloroplast may also indicate a defense response in compatible host-virus interaction.

Removal of the lower epidermis from cowpea and tobacco leaves inoculated with TMV or TNV resulted in reduction of local lesion numbers, indicating that the chloroplast-free epidermal cells possess an active role in virus infection (Wieringabrants, 1981). Further, chloroplast may also have a role in host defense against virus during the compatible plant-virus interaction. Previous studies found that light could influence host susceptibility to virus infection. Despite there is a report that a short burst of light after dark treatment enhances plant susceptibility to TMV infection (Helms and McIntyre, 1967), in most cases, low light and dark treatment is beneficial for viruses to establish infection and increase host's susceptibility compared to light treatment (Bawden and Roberts, 1947; Matthews, 1953; Wiltshire, 1956; Helms, 1965; Helms and McIntyre, 1967; Cheo, 1971; Manfre et al., 2011). The negative correlation between light and infectivity suggest that the robust photosynthesis and chloroplast function play a positive role in defense response during plant-virus interactions.

In compatible plant-virus interactions, some chloroplast factors are sequestrated by virus to block antiviral defense and fuel virus infection. For examples, AMV CP is essential for virus replication and encapsidation, and interacts with the chloroplast protein PsbP in the cytosol (Table 1), while mutations that prevent the dimerization of CP abolish this interaction (Balasubramaniam et al., 2014). Interestingly, overexpression of PsbP markedly reduced AMV replication in infected leaves, suggesting that there is a potential PsbP-mediated antiviral mechanism which was sequestered by CP-PsbP interaction (Balasubramaniam et al., 2014).

TMV 126-kD replicase associates with several CPRPs (Table 1) such as PsbO (Abbink et al., 2002), RCA and ATP-synthase γ-subunit (AtpC) (Bhat et al., 2013). Silencing of PsbO results in leaf chlorosis and elevated replication of several viruses including TMV, AMV, and PVX (Abbink et al., 2002). Similarly, suppression of AtpC and RCA enhances the accumulation of TMV and TVCV (Bhat et al., 2013). In addition, TMV infection specifically decreased the expression levels of AtpC, RCA, and PsbO (Abbink et al., 2002; Bhat et al., 2013). Further, silencing of RbCS enhances host susceptibility to ToMV and TMV, which is be accompanied by the reduced expression of pathogen related gene PR-1a (Zhao et al., 2013). These findings suggest that these CPRPs (RbCS, AtpC, RCA, and PsbO) play roles in plant defense against TMV, and TMV has evolved a strategy to suppress the defense of host plants for optimizing their own propagation.

The cylindrical inclusion (CI) protein of potyviruses is required for virus replication and cell-to-cell movement. CI protein from PPV and TVMV interacts with photosystem I PSI-K protein (Table 1), the product of the gene psaK in yeast (Jimenez et al., 2006). Overexpression of PPV CI reduces protein level of PSI-K while silencing or knockout of psaK enhances PPV accumulation in N. benthamiana and Arabidopsis, suggesting that chloroplast-localized PSI-K protein could have an antiviral role (Jimenez et al., 2006).

AltMV TGB1 can bind several chloroplast factors (Table 1), such as light harvesting chlorophyll-protein complex I subunit A4 (LhcA4), chlorophyll a/b binding protein 1 (LHB1B2), chloroplast-localized IscA-like protein (CPISCA) and chloroplast β-ATPase (CF1β) (Seo et al., 2014). Among those chloroplast proteins, CF1β selectively binds the wild type TGB1L88 with high RNAi suppressor activity (Table 1) but not the natural variant TGB1P88 with reduced silencing suppressor activity (Seo et al., 2014). During infection with wild type AltMV, silencing of CF1β specifically causes severe necrosis without a significant change of viral RNAs, suggesting a direct role of CF1β responding to TGB1L88 to induce defense responses (Seo et al., 2014). Taken together, the above reports indicate that the chloroplast plays an important defense role during virus invasion.

During incompatible plant-virus interactions, some chloroplast factors also participate in plant defense against viruses. For examples, in TMV resistance gene N containing tobacco, N receptor interacting protein 1 (NRIP1), a rhodanese sulfurtransferase which is destined to chloroplast under normal conditions, associates with both the tobacco N receptor and 126 K replicase during TMV infection; its relocation from chloroplast to cytoplasm and nucleus is required for N-mediated resistance to TMV (Caplan et al., 2008). Moreover, depletion of RbCS compromises Tm-22 mediated extreme resistance against ToMV and TMV (Zhao et al., 2013). In addition, chloroplast-localized calcium-sensing receptor is found to be involved in stromal Ca2+ transients and responsible for both basal resistance and R gene-mediated defense (Nomura et al., 2012). These observations are consistent with the idea that chloroplasts have a critical role in plant immunity as a major site for the production for ROS, SA, and JA, important mediators of plant immunity.

Taken together, chloroplast factors participate in both basal defense and R gene mediated immunity against viruses.

Conclusions and future perspectives

The disturbance of chloroplast structure or components is often involved in symptom development and some chloroplast proteins help viruses to fulfill their infection cycle in plants. On the other hand, chloroplast factors seem to play active roles in plant defense against viruses. This is consistent with the idea that ROS, SA, and JA are produced in chloroplast (Heiber et al., 2014).

So far, some chloroplast factors involved in virus symptomology, infection cycle or antiviral defense have been identified, and their roles in virus infection have been characterized. Some findings can explain phenomena observed in early reports. However, our understanding about chloroplast-virus interaction is still quite poor. In the future, we need to identify more chloroplast factors that take part in virus infection and plant defense against viruses, to unravel their precise role and functional mechanism during plant-virus interactions, to investigate how viruses modulate expression of CPRGs and chloroplast-derived signaling to affect plant response to viruses, and how viral factors or defense signals traffic between chloroplast and other cellular compartments. Further progress in understanding of chloroplast-virus interactions will open new possibilities in controlling virus infection by regulating host factor's expression level.

Author contributions

JZ wrote most part of this manuscript. XZ helped to write this manuscript. YL, YH supervised, revised and complemented the writing.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31530059, 31470254, 31300134, 31270182, and 31370180), the National Basic Research Program of China (2014CB138400), the Special Fund for Agro-scientific Research in the Public Interest of China (201303028), and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2014M550049), the Initial Funding of Zhejiang Academy of Agricultural Sciences, and the Cultural Funding for Youth Talent of Zhejiang Academy of Agricultural Sciences (2015R21R08E03).

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr. Oliver Terrett at Cambridge University for help in correcting the English of the manuscript.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AbMV

Abutilon mosaic virus

- AltMV

Alternanthera mosaic virus

- AMV

Alfalfa mosaic virus

- BaMV

Bamboo mosaic virus

- BSMV

Barley stripe mosaic virus

- CaMV

Cauliflower mosaic virus

- CI protein

Cylindrical inclusion protein

- CMV

Cucumber mosaic virus

- CNV

Cucumber necrosis virus

- CP

Coat protein, Capsid protein

- CPRG/CPRP

chloroplast photosynthesis-related gene/protein

- HC-Pro

Helper component protein proteinase

- JA

Jasmonic acid

- MDMV

Maize dwarf mosaic virus

- MP

Movement protein

- OEC

Oxygen evolving complex

- OYDV

Onion yellow dwarf virus

- PD

plasmodesmata

- PMTV

Potato mop-top virus

- PPV

Plum pox virus

- PS II

photosystem II

- PVX

Potato virus X

- PVY

Potato virus Y

- RCNMV

Red clover necrotic mosaic virus

- RdRP

RNA-dependent RNA polymerase

- R gene

Resistance gene

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- RSV

Rice stripe virus

- RuBisCO

Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase

- RYMV

Rice yellow mottle virus

- SA

Salicylic acid

- SCMV

Sugarcane mosaic virus

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- SMV

Soybean mosaic virus

- SNARE

soluble NSF attachment protein receptor

- SYSV

Shallot yellow stripe virus

- TBSV

Tomato bushy stunt virus

- TEV

Tobacco etch virus

- TGB proteins

Triple gene block proteins

- TMV

Tobacco mosaic virus

- TNV

Tobacco necrosis virus

- ToMV

Tomato mosaic virus

- TRSV

Tobacco ringspot virus

- TuMV

Turnip mosaic virus

- TVMV

Tobacco vein-mottling virus

- TYMV

Turnip yellow mosaic virus

- VRC

Viral replication complex

- WMV

Watermelon mosaic virus.

References

- Abbink T. E., Peart J. R., Mos T. N., Baulcombe D. C., Bol J. F., Linthorst H. J. (2002). Silencing of a gene encoding a protein component of the oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II enhances virus replication in plants. Virology 295, 307–319. 10.1006/viro.2002.1332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahlquist P. (2002). RNA-dependent RNA polymerases, viruses, and RNA silencing. Science 296, 1270–1273. 10.1126/science.1069132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahlquist P., Noueiry A. O., Lee W.-M., Kushner D. B., Dye B. T. (2003). Host factors in positive-strand RNA virus genome replication. J. Virol. 77, 8181–8186. 10.1128/JVI.77.15.8181-8186.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alazem M., Lin N.-S. (2015). Roles of plant hormones in the regulation of host–virus interactions. Mol. Plant Pathol. 16, 529–540. 10.1111/mpp.12204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan A. C., Lapidot M., Culver J. N., Fluhr R. (2001). An early tobacco mosaic virus-induced oxidative burst in tobacco indicates extracellular perception of the virus coat protein. Plant Physiol. 126, 97–108. 10.1104/pp.126.1.97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen T. C. (1972). Subcellular responses of mesophyll cells to wild cucumber mosaic virus. Virology 47, 467–474. 10.1016/0042-6822(72)90282-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almási A., Harsányi A., Gáborjányi R. (2001). Photosynthetic alterations of virus infected plants. Acta Phytopathol. Entomol. Hung 36, 15–29. 10.1556/APhyt.36.2001.1-2.3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Almon E., Horowitz M., Wang H. L., Lucas W. J., Zamski E., Wolf S. (1997). Phloem-specific expression of the tobacco mosaic virus movement protein alters carbon metabolism and partitioning in transgenic potato plants. Plant Physiol. 115, 1599–1607. 10.1104/pp.115.4.1599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angel C. A., Lutz L., Yang X., Rodriguez A., Adair A., Zhang Y., et al. (2013). The P6 protein of cauliflower mosaic virus interacts with CHUP1, a plant protein which moves chloroplasts on actin microfilaments. Virology 443, 363–374. 10.1016/j.virol.2013.05.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angell S. M., Baulcombe D. C. (1997). Consistent gene silencing in transgenic plants expressing a replicating potato virus X RNA. EMBO J. 16, 3675–3684. 10.1093/emboj/16.12.3675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appiano A., Pennazio S., Redolfi P. (1978). Cytological alterations in tissues of Gomphrena globosa plants systemically infected with tomato bushy stunt virus. J. Gen. Virol. 40, 277–286. 10.1099/0022-1317-40-2-277 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arnott H. J., Rosso S. W., Smith K. M. (1969). Modification of plastid ultrastructure in tomato leaf cells infected with tobacco mosaic virus. J. Ultrastruct. Res. 27, 149–167. 10.1016/S0022-5320(69)90025-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asada K. (2006). Production and scavenging of reactive oxygen species in chloroplasts and their functions. Plant Physiol. 141, 391–396. 10.1104/pp.106.082040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asurmendi S., Berg R. H., Koo J. C., Beachy R. N. (2004). Coat protein regulates formation of replication complexes during tobacco mosaic virus infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 1415–1420. 10.1073/pnas.0307778101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atreya C. D., Siegel A. (1989). Localization of multiple TMV encapsidation initiation sites on rbcL gene transcripts. Virology 168, 388–392. 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90280-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balachandran S., Osmond C. B., Daley P. F. (1994a). Diagnosis of the earliest strain-specific interactions between tobacco mosaic virus and chloroplasts of tobacco leaves in vivo by means of chlorophyll fluorescence imaging. Plant Physiol. 104, 1059–1065. 10.1104/pp.104.3.1059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balachandran S., Osmond C. B., Makino A. (1994b). Effects of two strains of tobacco mosaic virus on photosynthetic characteristics and nitrogen partitioning in leaves of Nicotiana tabacum cv Xanthi during photoacclimation under two nitrogen nutrition regimes. Plant Physiol. 104, 1043–1050. 10.1104/pp.104.3.1043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramaniam M., Kim B.-S., Hutchens-Williams H. M., Loesch-Fries L. S. (2014). The photosystem II oxygen-evolving complex protein PsbP interacts with the coat protein of alfalfa mosaic virus and inhibits virus replication. Mol. Plant. Microbe Interact 27, 1107–1118. 10.1094/MPMI-02-14-0035-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bald J. G. (1948). The development of amoeboid inclusion bodies of tobacco mosaic virus. Aust. J. Bot. Sci. 1, 458–463. 10.1071/BI9480458 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee N., Wang J.-Y., Zaitlin M. (1995). A single nucleotide change in the coat protein gene of tobacco mosaic virus is involved in the induction of severe chlorosis. Virology 207, 234–239. 10.1006/viro.1995.1070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee N., Zaitlin M. (1992). Import of tobacco mosaic virus coat protein into intact chloroplasts in vitro. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact 5, 466–471. 10.1094/MPMI-5-466 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bassi M., Appiano A., Barbieri N., D'Agostino G. (1985). Chloroplast alterations induced by tomato bushy stunt virus inDatura leaves. Protoplasma 126, 233–235. 10.1007/bf01281799 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baulcombe D. C. (1999). Fast forward genetics based on virus-induced gene silencing. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2, 109–113. 10.1016/S1369-5266(99)80022-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bawden F. C., Roberts F. M. (1947). The influence of light intensity on the susceptibility of plants to certain viruses. An. Appl. Biol. 34, 286–296. 10.1111/j.1744-7348.1947.tb06364.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betto E., Bassi M., Favali M. A., Conti G. G. (1972). An electron microscopic and autoradiographic study of tobacco leaves infected with the U5 strain of tobacco mosaic virus. J. Phytopathol. 75, 193–201. 10.1111/j.1439-0434.1972.tb02616.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat S., Folimonova S. Y., Cole A. B., Ballard K. D., Lei Z., Watson B. S., et al. (2013). Influence of host chloroplast proteins on Tobacco mosaic virus accumulation and intercellular movement. Plant Physiol. 161, 134–147. 10.1104/pp.112.207860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boatwright J. L., Pajerowska-Mukhtar K. (2013). Salicylic acid: an old hormone up to new tricks. Mol. Plant Pathol. 14, 623–634. 10.1111/mpp.12035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bové J., Bové C. (1985). Turnip yellow mosaic virus RNA replication on the chloroplast envelope. Physiol. Vég. 23, 741–748. [Google Scholar]

- Brizard J. P., Carapito C., Delalande F., Van Dorsselaer A., Brugidou C. (2006). Proteome analysis of plant-virus interactome: comprehensive data for virus multiplication inside their hosts. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 5, 2279–2297. 10.1074/mcp.M600173-MCP200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan J. L., Kumar A. S., Park E., Padmanabhan M. S., Hoban K., Modla S., et al. (2015). Chloroplast stromules function during innate immunity. Dev. Cell 34, 45–57. 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.05.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan J. L., Mamillapalli P., Burch-Smith T. M., Czymmek K., Dinesh-Kumar S. P. (2008). Chloroplastic protein NRIP1 mediates innate immune receptor recognition of a viral effector. Cell 132, 449–462. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll T. W. (1970). Relation of barley stripe mosaic virus to plastids. Virology 42, 1015–1022. 10.1016/0042-6822(70)90350-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng S.-F., Huang Y.-P., Chen L.-H., Hsu Y.-H., Tsai C.-H. (2013). Chloroplast phosphoglycerate kinase is involved in the targeting of bamboo mosaic virus to chloroplasts in Nicotiana benthamiana plants. Plant Physiol. 163, 1598–1608. 10.1104/pp.113.229666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y.-Q., Liu Z.-M., Xu J., Zhou T., Wang M., Chen Y.-T., et al. (2008). HC-Pro protein of sugar cane mosaic virus interacts specifically with maize ferredoxin-5 in vitro and in planta. J. Gen. Virol. 89, 2046–2054. 10.1099/vir.0.2008/001271-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheo P. C. (1971). Effect in different plant species of continuous light and dark treatment on tobacco mosaic virus replicating capacity. Virology 46, 256–265. 10.1016/0042-6822(71)90028-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chini A., Fonseca S., Fernández G., Adie B., Chico J. M., Lorenzo O., et al. (2007). The JAZ family of repressors is the missing link in jasmonate signalling. Nature 448, 666–671. 10.1038/nature06006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi C. W. (1996). Cytological modification of sorghum leaf tissues showing the early acute response to maize dwarf mosaic virus. J Plant Biol 39, 215–221. [Google Scholar]

- Christov I., Stefanov D., Velinov T., Goltsev V., Georgieva K., Abracheva P., et al. (2007). The symptomless leaf infection with grapevine leafroll associated virus 3 in grown in vitro plants as a simple model system for investigation of viral effects on photosynthesis. J. Plant Physiol. 164, 1124–1133. 10.1016/j.jplph.2005.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citovsky V., Knorr D., Schuster G., Zambryski P. (1990). The P30 movement protein of tobacco mosaic virus is a single-strand nucleic acid binding protein. Cell 60, 637–647. 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90667-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemente-Moreno M. J., Díaz-Vivancos P., Rubio M., Fernández-García N., Hernández J. A. (2013). Chloroplast protection in plum pox virus-infected peach plants by L-2-oxo-4-thiazolidine-carboxylic acid treatments: effect in the proteome. Plant Cell Environ. 36, 640–654. 10.1111/pce.12003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan G. H., Roberts A. G., Chapman S. N., Ziegler A., Savenkov E. I., Torrance L. (2012). The potato mop-top virus TGB2 protein and viral RNA associate with chloroplasts and viral infection induces inclusions in the plastids. Front. Plant Sci. 3:290. 10.3389/fpls.2012.00290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Graça J. V., Martin M. M. (1975). Ultrastructural changes in tobacco mosaic virus-induced local lesions in Nicotiana tabacum L. cv. “Samsun NN”. Physiol. Plant Pathol. 7, 287–291. 10.1016/0048-4059(75)90033-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dardick C. (2007). Comparative expression profiling of Nicotiana benthamiana leaves systemically infected with three fruit tree viruses. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact 20, 1004–1017. 10.1094/mpmi-20-8-1004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Graaff M., Coscoy L., Jaspars E. M. J. (1993). Localization and biochemical characterization of Alfalfa mosaic virus replication complexes. Virology 194, 878–881. 10.1006/viro.1993.1335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Stradis A., Redinbaugh M., Abt J., Martelli G. (2005). Ultrastructure of maize necrotic streak virus infections. J. Plant Pathol. 87, 213–221. 10.4454/jpp.v87i3.920 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Vivancos P., Clemente-Moreno M. J., Rubio M., Olmos E., García J. A., Martínez-Gómez P., et al. (2008). Alteration in the chloroplastic metabolism leads to ROS accumulation in pea plants in response to plum pox virus. J. Exp. Bot. 59, 2147–2160. 10.1093/jxb/ern082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding B., Haudenshield J. S., Hull R. J., Wolf S., Beachy R. N., Lucas W. J. (1992). Secondary plasmodesmata are specific sites of localization of the tobacco mosaic virus movement protein in transgenic tobacco plants. Plant Cell 4, 915–928. 10.1105/tpc.4.8.915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreher T. W. (2004). Turnip yellow mosaic virus: transfer RNA mimicry, chloroplasts and a C-rich genome. Mol. Plant Pathol. 5, 367–375. 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2004.00236.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Fattah A. A., El-Din H. A. N., Abodoah A., Sadik A. (2005). Occurrence of two sugarcane mosaic potyvirus strains in sugarcane. Pak. J. Biotechnol. 2, 1–12. Available online at: http://www.pjbt.org/publications.php?year=2005myModal_1 [Google Scholar]

- Falcioni T., Ferrio J. P., del Cueto A. I., Giné J., Achón M. Á., Medina V. (2014). Effect of salicylic acid treatment on tomato plant physiology and tolerance to potato virus X infection. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 138, 331–345. 10.1007/s10658-013-0333-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feki S., Loukili M. J., Triki-Marrakchi R., Karimova G., Old I., Ounouna H., et al. (2005). Interaction between tobacco ribulose-1,5-biphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase large subunit (RubisCO-LSU) and the PVY coat protein (PVY-CP). Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 112, 221–234. 10.1007/s10658-004-6807-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Filée J., Forterre P. (2005). Viral proteins functioning in organelles: a cryptic origin? Trends Microbiol. 13, 510–513. 10.1016/j.tim.2005.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser R. S. S. (1969). Effects of two TMV strains on the synthesis and stability of chloroplast ribosomal RNA in tobacco leaves. Mol. Gen. Genet. 106, 73–79. 10.1007/BF00332822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara T., Giesman-Cookmeyer D., Ding B., Lommel S. A., Lucas W. J. (1993). Cell-to-cell trafficking of macromolecules through plasmodesmata potentiated by the red clover necrotic mosaic virus movement protein. Plant Cell 5, 1783–1794. 10.1105/tpc.5.12.1783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadh I. P. S., Hari V. (1986). Association of tobacco etch virus related RNA with chloroplasts in extracts of infected plants. Virology 150, 304–307. 10.1016/0042-6822(86)90292-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Q.-M., Venugopal S., Navarre D., Kachroo A. (2011). Low oleic acid-derived repression of jasmonic acid-inducible defense responses requires the WRKY50 and WRKY51 proteins. Plant Physiol. 155, 464–476. 10.1104/pp.110.166876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Marcos A., Pacheco R., Manzano A., Aguilar E., Tenllado F. (2013). Oxylipin biosynthesis genes positively regulate programmed cell death during compatible infections with the synergistic pair potato virus X-potato virus Y and tomato spotted wilt virus. J. Virol. 87, 5769–5783. 10.1128/jvi.03573-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcion C., Lohmann A., Lamodière E., Catinot J., Buchala A., Doermann P., et al. (2008). Characterization and biological function of the ISOCHORISMATE SYNTHASE2 gene of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 147, 1279–1287. 10.1104/pp.108.119420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg I., Hegde V. (2000). Biological characterization, preservation and ultrastructural studies of Andean strain of potato virus S. Indian Phytopathol. 53, 256–260. Available online at: http://epubs.icar.org.in/ejournal/index.php/IPPJ/article/view/19306 [Google Scholar]

- Garnier M., Candresse T., Bove J. M. (1986). Immunocytochemical localization of TYMV-coded structural and nonstructural proteins by the protein A-gold technique. Virology 151, 100–109. 10.1016/0042-6822(86)90107-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]