Abstract

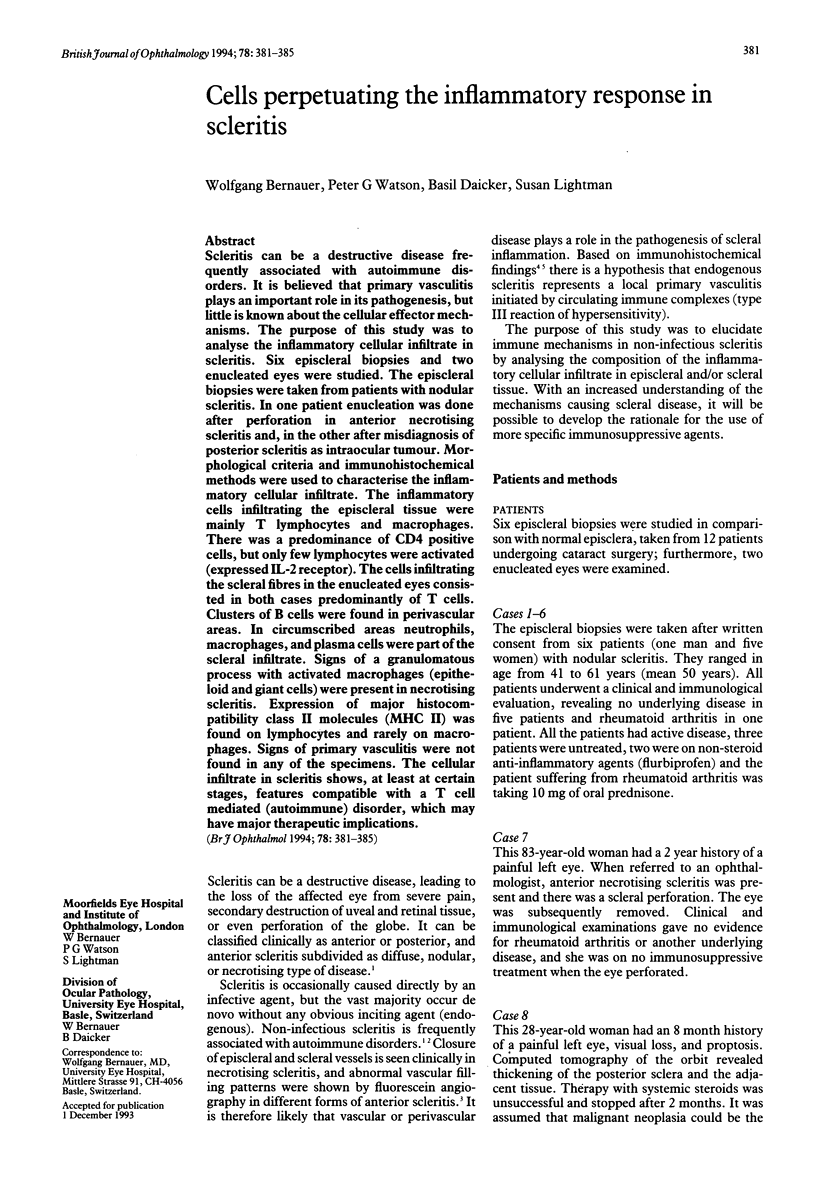

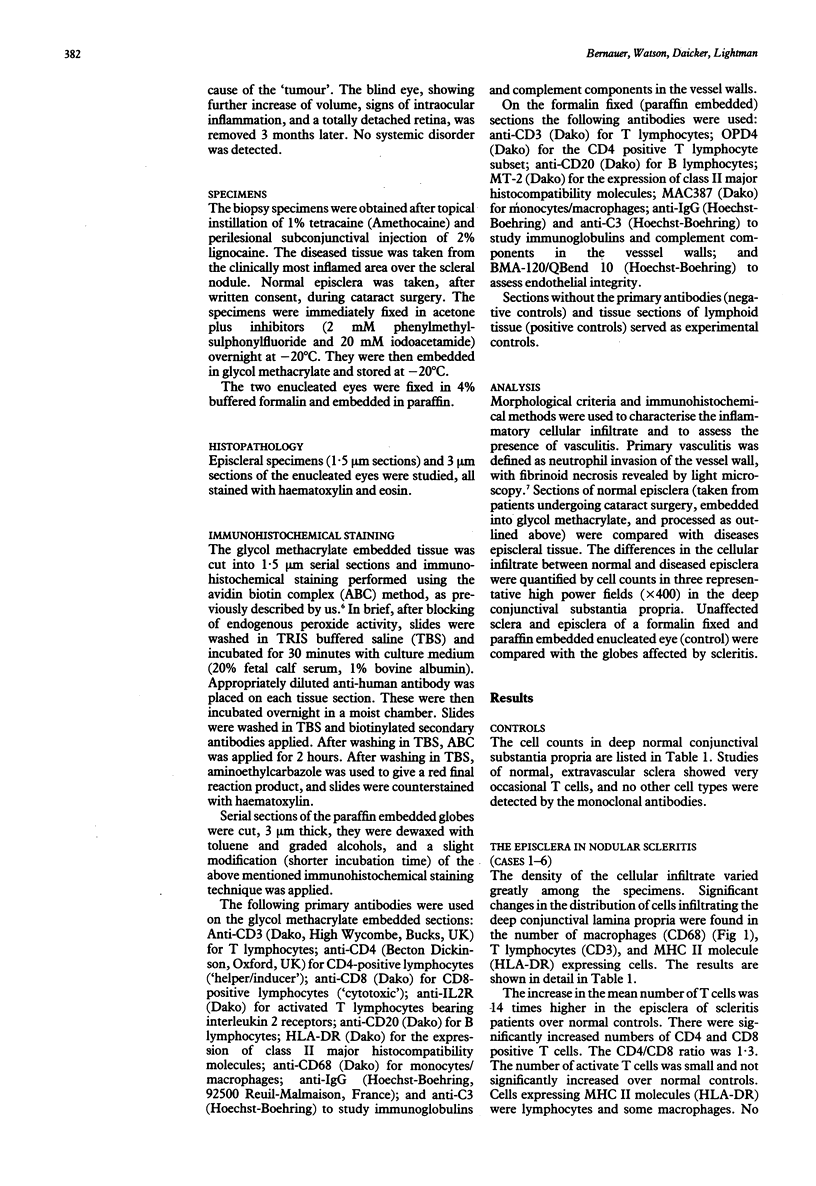

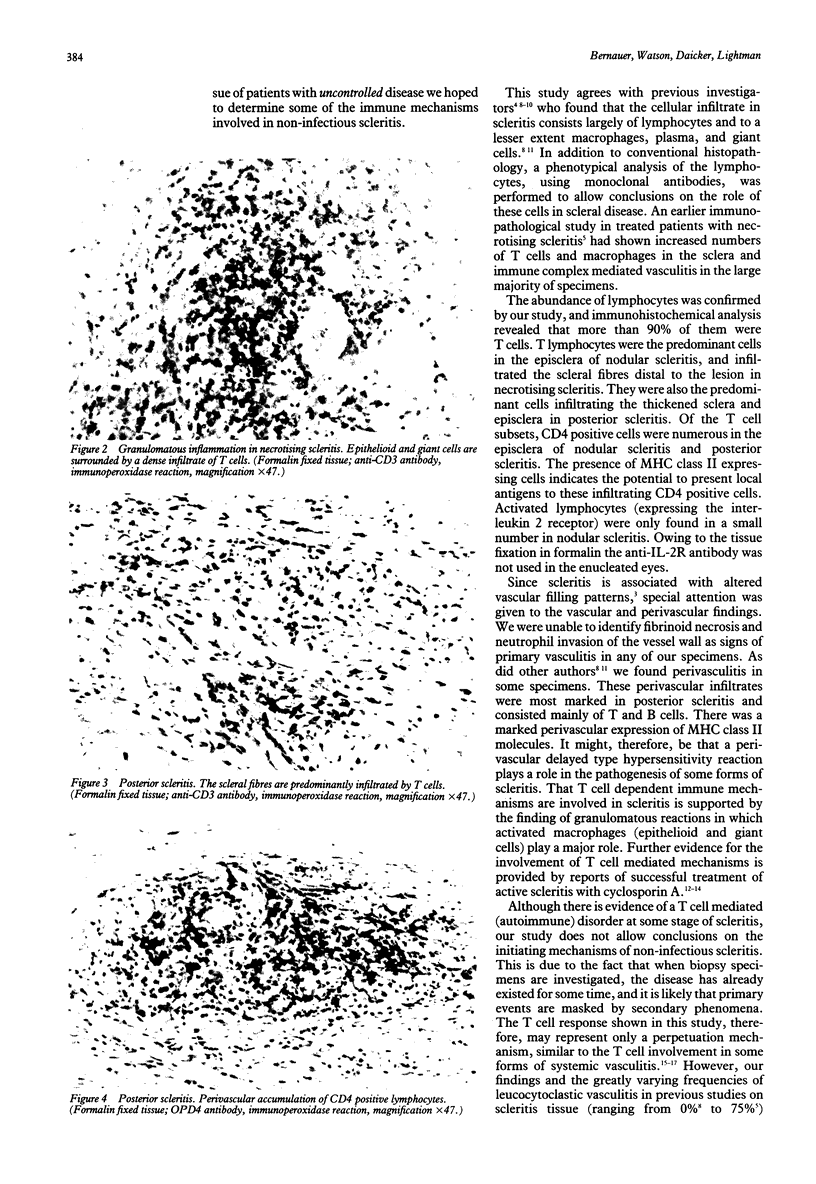

Scleritis can be a destructive disease frequently associated with autoimmune disorders. It is believed that primary vasculitis plays an important role in its pathogenesis, but little is known about the cellular effector mechanisms. The purpose of this study was to analyse the inflammatory cellular infiltrate in scleritis. Six episcleral biopsies and two enucleated eyes were studied. The episcleral biopsies were taken from patients with nodular scleritis. In one patient enucleation was done after perforation in anterior necrotising scleritis and, in the other after misdiagnosis of posterior scleritis as intraocular tumour. Morphological criteria and immunohistochemical methods were used to characterise the inflammatory cellular infiltrate. The inflammatory cells infiltrating the episcleral tissue were mainly T lymphocytes and macrophages. There was a predominance of CD4 positive cells, but only few lymphocytes were activated (expressed IL-2 receptor). The cells infiltrating the scleral fibres in the enucleated eyes consisted in both cases predominantly of T cells. Clusters of B cells were found in perivascular areas. In circumscribed areas neutrophils, macrophages, and plasma cells were part of the scleral infiltrate. Signs of a granulomatous process with activated macrophages (epithelioid and giant cells) were present in necrotising scleritis. Expression of major histocompatibility class II molecules (MHC II) was found on lymphocytes and rarely on macrophages. Signs of primary vasculitis were not found in any of the specimens. The cellular infiltrate in scleritis shows, at least at certain stages, features compatible with a T cell mediated (autoimmune) disorder, which may have major therapeutic implications.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Benson W. E. Posterior scleritis. Surv Ophthalmol. 1988 Mar-Apr;32(5):297–316. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(88)90093-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernauer W., Wright P., Dart J. K., Leonard J. N., Lightman S. The conjunctiva in acute and chronic mucous membrane pemphigoid. An immunohistochemical analysis. Ophthalmology. 1993 Mar;100(3):339–346. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(93)31644-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong L. P., Sainz de la Maza M., Rice B. A., Kupferman A. E., Foster C. S. Immunopathology of scleritis. Ophthalmology. 1991 Apr;98(4):472–479. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(91)32280-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakin K. N., Ham J., Lightman S. L. Use of cyclosporin in the management of steroid dependent non-necrotising scleritis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1991 Jun;75(6):340–341. doi: 10.1136/bjo.75.6.340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennette J. C., Wilkman A. S., Falk R. J. Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody-associated glomerulonephritis and vasculitis. Am J Pathol. 1989 Nov;135(5):921–930. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathieson P. W., Cobbold S. P., Hale G., Clark M. R., Oliveira D. B., Lockwood C. M., Waldmann H. Monoclonal-antibody therapy in systemic vasculitis. N Engl J Med. 1990 Jul 26;323(4):250–254. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199007263230407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy J. M., Dubord P. J., Chalmers A., Kassen B. O., Rangno K. K. Cyclosporine A for the treatment of necrotizing scleritis and corneal melting in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1992 Sep;19(9):1358–1361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao N. A., Marak G. E., Hidayat A. A. Necrotizing scleritis. A clinico-pathologic study of 41 cases. Ophthalmology. 1985 Nov;92(11):1542–1549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sainz de la Maza M., Foster C. S. Necrotizing scleritis after ocular surgery. A clinicopathologic study. Ophthalmology. 1991 Nov;98(11):1720–1726. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(91)32062-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevel D. Necrogranulomatous scleritis. Clinical and histologic features. Am J Ophthalmol. 1967 Dec;64(6):1125–1134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakefield D., McCluskey P. Cyclosporin therapy for severe scleritis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1989 Sep;73(9):743–746. doi: 10.1136/bjo.73.9.743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson P. G., Bovey E. Anterior segment fluorescein angiography in the diagnosis of scleral inflammation. Ophthalmology. 1985 Jan;92(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(85)34074-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson P. G., Hayreh S. S. Scleritis and episcleritis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1976 Mar;60(3):163–191. doi: 10.1136/bjo.60.3.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young R. D., Watson P. G. Microscopical studies of necrotising scleritis. I. Cellular aspects. Br J Ophthalmol. 1984 Nov;68(11):770–780. doi: 10.1136/bjo.68.11.770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]