Abstract

This paper proposes a new plant-inspired optimization algorithm for multilevel threshold image segmentation, namely, hybrid artificial root foraging optimizer (HARFO), which essentially mimics the iterative root foraging behaviors. In this algorithm the new growth operators of branching, regrowing, and shrinkage are initially designed to optimize continuous space search by combining root-to-root communication and coevolution mechanism. With the auxin-regulated scheme, various root growth operators are guided systematically. With root-to-root communication, individuals exchange information in different efficient topologies, which essentially improve the exploration ability. With coevolution mechanism, the hierarchical spatial population driven by evolutionary pressure of multiple subpopulations is structured, which ensure that the diversity of root population is well maintained. The comparative results on a suit of benchmarks show the superiority of the proposed algorithm. Finally, the proposed HARFO algorithm is applied to handle the complex image segmentation problem based on multilevel threshold. Computational results of this approach on a set of tested images show the outperformance of the proposed algorithm in terms of optimization accuracy computation efficiency.

1. Introduction

Image segmentation is an important image preprocessing technique with primitive operations for image recognition [1, 2]. The goal of image segmentation is to partition an original image into a suit of disjoint sections or regions by gray values and texture structures [3]. Generally, there is a strong correlation between the objects of these disjoint regions in the image. Bithreshold or multilevel threshold based segmentation methods have been deeply developed and employed in various practical applications. The key issue to this segmentation method is the computational determination of the involved threshold. A broad variety of threshold based segmentation methods have been proposed, including conventional approaches [4] and intelligent approaches [5, 6]. Among them, the classical Otsu criterion shows significant merits of simplicity and high efficiency, which determines the appropriate thresholds according to intrinsic profile characteristic of histogram [7]. As a matter of fact, the Otsu transforms the multilevel threshold segmentation into an optimization problem, which tends to maximize intercluster variance of subpartition. However, due to the exhaustive property of this approach, the computational complexity will rise exponentially with the increasing of the threshold number [8, 9].

Recently, due to their excellent abilities of tackling complex NP-hard problems, metaheuristics such as artificial bee colony [10, 11], particle swarm optimization [12], artificial ant colony [13], differential evolution [14], firefly algorithm [15], wind driven optimization [16], and bacterial foraging algorithm [17] have been adopted widely in threshold image segmentation. It is worth noting that those metaheuristics are generally inspired form intelligent behaviors of animals that have foraging strategies. The survival wisdom of plants, as another typical species of foraging organisms, has received little attention due to their specific lifestyle [18]. However, terrestrial plants have prominent adaptability and sensing ability to use environmental information as a basis for governing their growth orientation and root system development [19]. Logically, such adaptive growth processes can provide novel insights into new computing paradigm for global optimization [20–22]. References [23, 24] have proposed and developed the novel and effective EA variants by using a hybridization of life-cycle and optimal search strategies and obtain significant performance improvement, which shows a novel and effective computation framework for related scientists. How to deliberately design novel evolutionary computation model and algorithm is increasingly becoming an area of active research; taking a promising example, a representative ARFO algorithm is proposed by Ma et al. in [22] and has received a surge of attention [23, 24]. Essentially, the ARFO provides an open and extensible biocomputation framework and model for scientists in the field of optimization theory to exploit new bioinspired algorithms.

Thus, this paper develops a novel hybrid artificial root foraging optimizer (HARFO) which synergizes the idea of coevolution and root-to-root communication strategy. In the proposed model, all roots can be generally divided into the main roots and lateral roots according to the auxin concentration. The main root as the strongest individuals can branch and regrow under effect of hydrotropism. The lateral root involves many branches derived from the main root, and its growth direction orients from corresponding main root [25, 26]. Furthermore, in the root-to-root communication, through different effective topology, individual roots share more information from the elite roots in the early exploration stage of the algorithm. With multipopulation coevolution mechanism, the hierarchical population of roots can be structured with enhanced interactions of individual behaviors from different subpopulations. By incorporating a set of hybrid strategies, the proposed HARFO can be claimed very effective and efficient because the exploitation and exploration can be elaborately balanced, which guarantees finding the optimal thresholds at a more reasonable time.

This paper is structured as follows: In Section 2, a brief overview of the proposed hybrid artificial root foraging optimizer model and algorithm is presented. Section 3 experimentally compares HARFO with other well-known algorithms on a set of benchmark functions. In Section 4 the implementation of HARFO for multilevel threshold for image segmentation is conducted. In Section 5 final conclusion is outlined.

2. Hybrid Artificial Root Foraging Optimizer

2.1. Artificial Root Foraging Optimization (ARFO) Model

This section briefly describes the classical ARFO proposed in [22], which simulates the intelligent foraging behaviors of plant roots. As depicted in [22], in order to idealize biological plant root growth behaviors, some criteria are presented as follows.

Auxin Concentration

-

The root's adaptive growth is conducted by auxin concentration, which significantly influences the information exchange among root tips. The auxin concentration regulates the roots' spatial structure, after new roots germinate and grow, and it is dynamically reallocated instead of static.

Growth Strategies

-

Regrowing: one root apex elongates forward (or sideways) in the substrate.

-

Branching: one root apex produces daughter root apices.

Root Classification

-

The whole root system generally consists of three categories sorted by the auxin concentration from high to low: the main roots, the lateral roots, and the dead roots

Root Tropisms

-

The growth trajectory of plant roots is influenced by hydrotropism, which makes the growing direction of the root tips towards the optimal individual position.

Generally, each root implements different growth strategies and operators according to the above criteria. Each main root regrows (i.e., elongates itself) while branching new individuals once some conditions are met. After each growth cycle, some deteriorated roots are selected as the dead roots to be eliminated from current population.

2.1.1. Auxin Regulation

Supposing that A i as the auxin concentration is used to exhibit the nutrient distribution in artificial soil environment, then it can be stated mathematically as below:

| (1) |

Then

| (2) |

where fitnessi is the functional fitness value, f i is the normalization fitness value of the root i, f min and f max are the maximum and minimum of the current population, respectively, and S is the size of current population. In each cycle of root growth process, all root taps are sorted by auxin concentration values defined above. In our model, half of the sorted population are selected as main roots while the rest of roots are identified as lateral roots.

2.1.2. Main Roots' Growth: Regrowing and Branching

According to the growth strategy of main root in criterion for the plant root growth behaviors, a main root with high A i value has strong growth ability of implementing both regrowing operator and branching operator.

(i) Regrowing Operator. In this regrowing process, the strong main root can sense environmental stimuli (i.e., nutrient distribution) and use this information to govern its growth orientation. Then, the formulation of this operator is given as below:

| (3) |

where x i t and x i t−1 are defined as the position of root i at time step t and t − 1, respectively, l is a local learning inertia, rand is a random coefficient varying within [0,1], and x lbest is the local best individual in current population.

(ii) Branching Operator. The main roots with higher auxin concentration values have higher probability to branch more individuals. In this operator, for each main root, if its auxin concentration value is more than a branching threshold T_Branch, it will start generating a certain number of new individuals as follows:

| (4) |

In principle, the main root in nutrient-rich environment will forage for energy to obtain higher auxin concentration and then produces more branches. Thus, the branch number w i can be calculated as

| (5) |

where R 1 is a random coefficient within the range [0,1], A i is the auxin concentration of root i, and S max and S min are the maximal number and minimal number of the new branching individuals, respectively, which are usually preset to 4 and 1, respectively.

The position of a newly branching root is initialized from the parent main root with Gauss distribution N(x i t, σ 2), where σ can be defined as

| (6) |

where i is the current iteration index, i max is the maximum of iterations, the initial standard deviation σ ini is determined by the range of searching, and σ fin donates the final standard deviation.

2.1.3. Lateral Roots Growth: Random Walking

At the tth iteration, each lateral root tip generates a random head angle and a random elongation length, given as follows: all lateral roots will conduct random searches at each feeding process; random search strategy is considered to be the most effective foraging strategy in nutrient distributed environment [27, 28]. Each lateral root generates a random growth angle and random elongated length, which is given by

| (7) |

where l max is the maximum elongate length unit (i.e., objective function boundary range), rand is a random number with uniform distribution in [0,1], and φ is a growth angle computed by a random vector δ i.

2.1.4. Dead Roots' Growth: Shrinkage

In the case that the root does not get enough nutrients from soil, its corresponding auxin concentration is intended to be weak. Once auxin concentration is lower than a certain threshold, the sustained growth probability will be stagnated. This enables the corresponding root to be simply removed from the current population. The branching criterion and dead roots eliminating criterion are listed as follows:

| (8) |

where N i is the current population size, T_Branch is the branching threshold, w i is the branching number defined by (5), and T_Nmority is the death threshold.

2.2. Root-to-Root Communication

The intrinsic property of the “population” in swarm intelligence is collective intelligence emerging by a number of connected individuals exchanging information in some specific topologies [27–30]. This means that the spatial topological structure plays an important role in enhancing dynamic interaction between individuals and optimizing information propagation path across the structured population.

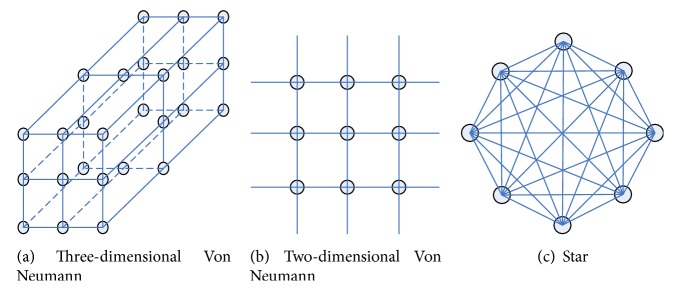

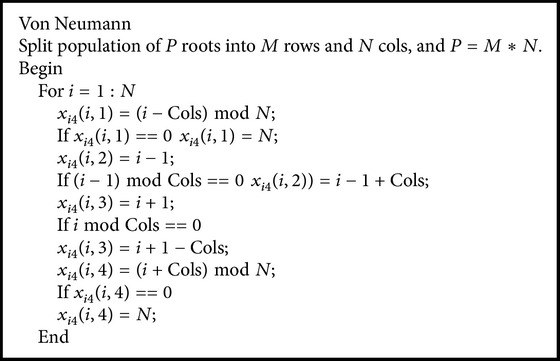

Accordingly, the population topology technique has been strongly recommended for potential improvement of swarm intelligence or evolutionary algorithms [30–33]. Particularly, by lucubrating on the relationship between population topologies structure and algorithmic performances in [29], Kennedy and Mendes conclude that the Von Neumann exhibits better convergence speed on a variety of test functions, as shown Figures 1(a) and 1(b).

Figure 1.

Population topology.

In ARFO, (3) shows that an individual's candidate neighborhood termed x lbest is selected from the entire population, which indicates one central node influences, and is influenced by all other members of the population [26]. In other words, this population topological structure of ARFO essentially falls into the star topology, which is a fully connected neighborhood relation, as shown in Figure 1(c). From [29], it is claimed that the Von Neumann has a lower connectivity while covers a larger search space than the star type, which tends to maintain better diversity of population and reduces the chances of falling into local optima. The procedures of representing Von Neumann structure are listed in Algorithm 1.

Algorithm 1.

The pseudocode of Von Neumann.

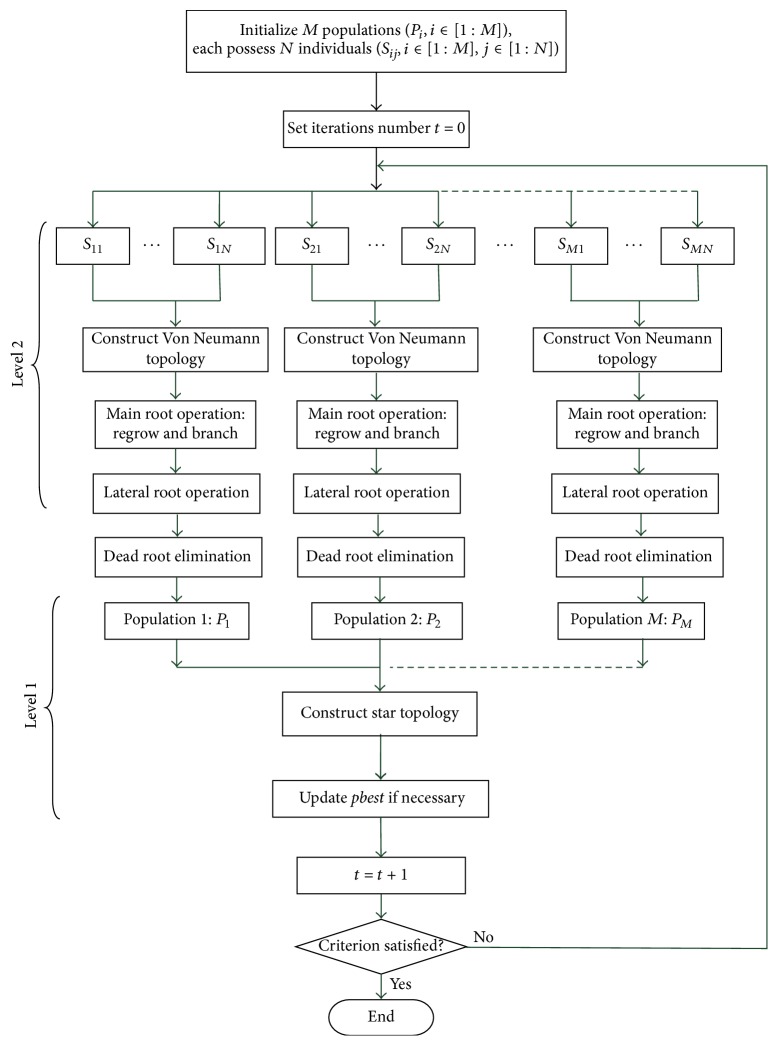

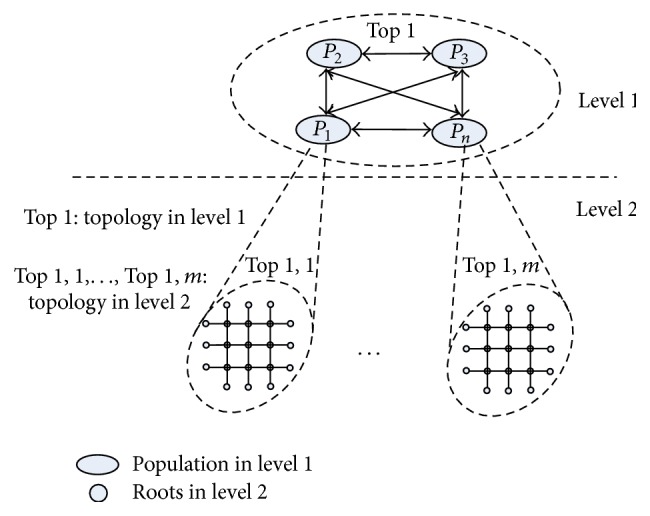

2.3. Coevolution Mechanism

Hierarchy is a common phenomenon in the development of plant root system [25, 26]. With the severity of environmental stress, homogeneous main roots continuously self-grow-branch and evolve while being a part of heterogeneous roots of different plant types and that plant is in turn a part of a specific ecosystem niche [27]. As a result, this hierarchical coevolution approach is incorporated to improve algorithm efficiency via decomposing large-scale problems into simple tasks optimized in parallel. As depicted in Figure 2, the flat ARFO is structured into two levels with different topologies as follows.

Figure 2.

Multispecies coevolution mechanism.

Hypothesize that population P = {S 1, S 2,…, S M}, and each swarm S k = {x 1, x 2,…, x N}. In each growth phase, the new individual or agent in level 2 is defined as

| (9) |

where x ibest t−1 is the best individual within current population which denotes cooperation in level 2 and x pbest t−1 is the global best individual among all populations which exchanges information across populations in level 1. l 1 and l 2 are the random coefficients. rand1 and rand2 are random numbers with uniform distribution in [0,1], respectively.

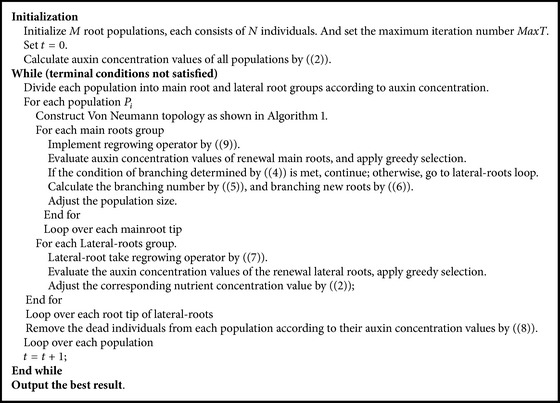

2.4. The Proposed Algorithm

By hybridizing ARFO with these complex degrees of strategies, namely, root-to-root communication and coevolution mechanism, the hybrid artificial root growth optimizer (HARFO) can regulate the trajectory of each root through the specific topology. Moreover, the evolution of population is guided by historical experience in level 2 and global best information in level 1, which can imply diversity of population. The main procedures of the proposed HARFO are listed in Algorithm 2. The flowchart of HARFO is presented in Figure 3.

Algorithm 2.

The pseudocode of HARFO.

Figure 3.

The flowchart of HARFO algorithm.

3. Benchmark Test

3.1. Test Functions

For the purpose of performance comparison, the HARFO, together with other state-of-the-art metaheuristic algorithms, is evaluated on a set of test functions from basic benchmarks and CEC 2005 test beds. The definition and mathematical representation of them are available in Table 1 where f 1~f 5 are basic benchmark functions and f 6~f 10 are taken from CEC 2005 test suit, which is complex rotation and shift problem based on the basic test functions.

Table 1.

Parameters of basic benchmarks and CEC 2005 benchmarks (x ∗ is the optimal solution, f(x ∗) is the best values of function).

| f | Functions | Dimensions | Initial range | x ∗ | f(x ∗) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| f 1 | Sphere function | 20 | [−100,100]D | [0,0,…, 0] | 0 |

| f 2 | Rosenbrock function | 20 | [−30,30]D | [1,1,…, 1] | 0 |

| f 3 | Rastrigrin function | 20 | [−5.12,5.12]D | [0,0,…, 0] | 0 |

| f 4 | Schwefel function | 20 | [−500, 500]D | [420.9867,…, 420.9867] | 0 |

| f 5 | Griewank function | 20 | [−600,600]D | [0,0,…, 0] | 0 |

| f 6 | Shifted Sphere Function | 20 | [−100, 100]D | [0,0,…, 0] | −450 |

| f 7 | Shifted Rosenbrock's Function | 20 | [−100, 100]D | [0,0,…, 0] | 390 |

| f 8 | Shifted Schwefel's Problem | 20 | [−100, 100]D | [0,0,…, 0] | −450 |

| f 9 | Shifted Rotated Griewank's Function without Bounds | 20 | No bounds | [0,0,…, 0] | −180 |

| f 10 | Shifted Rastrigin's Function | 20 | [−5,5]D | [0,0,…, 0] | −330 |

Furthermore, in order to comprehensively evaluate the performance of the proposed algorithm, a suit of scalable shifted and rotated benchmarks from CEC 2014 test bed is employed in the test [34–36]. The dimensions, initialization ranges, and global optimum of each function (f 11~f 20) are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Parameters of CEC 2014 test functions (x ∗ is the optimal solution; f(x ∗) is the best values of function; and O i is the shifted global optimum defined in “shift_data_x.txt,” which is randomly distributed in [−80,80]D).

| f | Functions | Dimensions | Initial range | x ∗ | f(x ∗) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| f 11 | Rotated High Conditioned Elliptic Function | 30 | [−100,100]D | O 1 | 100 |

| f 12 | Rotated Bent Cigar Function | 30 | [−100,100]D | O 2 | 200 |

| f 13 | Rotated Discus Function | 30 | [−100,100]D | O 3 | 300 |

| f 14 | Shifted and Rotated Rosenbrock's Function | 30 | [−100,100]D | O 4 | 400 |

| f 15 | Shifted and Rotated Ackley's Function | 30 | [−100,100]D | O 5 | 500 |

| f 16 | Shifted and Rotated Weierstrass Function | 30 | [−100,100]D | O 6 | 600 |

| f 17 | Shifted and Rotated Griewank's Function | 30 | [−100,100]D | O 7 | 700 |

| f 18 | Shifted Rastrigin's Function | 30 | [−100,100]D | O 8 | 800 |

| f 19 | Shifted and Rotated Rastrigin's Function | 30 | [−100,100]D | O 9 | 900 |

| f 20 | Shifted Schwefel's Function | 30 | [−100,100]D | O 10 | 1000 |

3.2. Experimental Configuration

For the purpose of performance comparison, the HARFO is compared with several classical evolutionary algorithms including particle swarm optimization (PSO) [37, 38], cooperative coevolution genetic algorithm (CCGA) [39], pure artificial root foraging optimization algorithm (ARFO) [22], and artificial bee colony algorithm (ABC) [20] on ten test benchmarks given above. Specifically, CCGA is a parallelized GA variant derived from the dimension-distributed coevolution mode, which divides a high-dimensional problem into several lower-dimensional subproblems and then assigns them to corresponding subswarms to coevolve [39]. On each function, the algorithm is independently run 20 times and terminated when the number of function evaluations reaches 100,000 for each run. The common population size associated with ARFO, PSO, and ABC is set to 20.

For PSO, the global version with inertia weight is adopted, and its parameters directly follow the default setting of [37, 38]: the acceleration factors c 1 = c 2 = 2.0 and the decaying inertia weight ω starting at 0.9 and ending at 0.4. For ABC, the limit is set to SN × D, where D is the dimension of the problem and SN is half of population size [20]. For CCGA, the subswarm number is set to 10, and other parameters are the same as its original literature [39]. The parameter setting of HARFO and ARFO can be empirically summarized in Table 3. For the proposed HARFO, the population number N, the branching, and dead thresholds should be tuned firstly in next section.

Table 3.

Parameters of HARFO and ARFO for optimization.

| HARFO | |

|---|---|

| The number of initial population | 20 |

| The maximum number of population | 100 |

| T_Branch | 10 |

| T_Nmority | 5 |

| S max | 4 |

| S min | 1 |

| Population number | 8 |

| The number of initial population | 4 |

| The maximum number of single population | 50 |

| BranchG | 10 |

| Nmority | 5 |

| S max | 4 |

| S min | 1 |

3.3. Parameters Sensitivity

(i) Sensitivity in relation to Population Number M in Level 1. To scientifically assess the effect of parameter M, the following experiment is designed. First, T_Branch and T_Nmority are assigned empirically with initial values 10 and 5, respectively. Then M is varied from 2 to 17 with a step size 3. For each value of M, HARFO is implemented for 20 times on six selected 30-dimensional f 11, f 12, f 13, f 14, and f 15. And computation results in terms of mean and standard deviation are given in Table 4. It can be visibly observed from Table 4 that algorithm with M equal to 2 and 8 can perform superior to that with other M values. Compared with M = 2, the result of algorithm with M = 8 is relatively better on three of five test benchmarks. Therefore, the optimal setting of the parameter M can be M = 8 as general usage of the algorithm.

Table 4.

Results obtained by HARFO with different population number.

| M | 2 | 5 | 8 | 11 | 14 | 17 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| f 11 | Mean | 1.9663E + 01 | 3.0644E + 01 | 2.0535E + 01 | 3.4134E + 01 | 3.7901E + 01 | 3.4393E + 01 |

| Std | 6.5353E − 01 | 7.3232E − 01 | 4.9023E − 01 | 8.1423E − 01 | 9.0482E − 01 | 8.2108E − 01 | |

|

| |||||||

| f 12 | Mean | 6.5523E + 01 | 7.3533E + 01 | 4.9234E + 01 | 8.1788E + 01 | 9.0872E + 01 | 8.2462E + 01 |

| Std | 1.1212E + 02 | 1.2511E + 02 | 8.4181E + 01 | 1.3922E + 02 | 1.5537E + 02 | 1.4099E + 02 | |

|

| |||||||

| f 13 | Mean | 3.1865E + 01 | 3.5876E + 01 | 3.7405E + 01 | 6.2144E + 01 | 6.9037E + 01 | 6.2648E + 01 |

| Std | 1.0089E + 01 | 1.9254E + 01 | 1.2886E + 01 | 2.1429E + 01 | 2.3784E + 01 | 2.1583E + 01 | |

|

| |||||||

| f 14 | Mean | 3.7411E + 01 | 4.1955E + 01 | 2.8088E + 01 | 4.6603E + 01 | 5.1842E + 01 | 4.7044E + 01 |

| Std | 9.6699E − 01 | 1.0881E + 00 | 7.2544E − 01 | 1.2127E + 00 | 1.3389E + 00 | 1.2150E + 00 | |

|

| |||||||

| f 15 | Mean | 7.9732E + 01 | 8.9323E + 01 | 5.9839E + 01 | 9.9226E + 01 | 1.1045E + 02 | 1.0022E + 02 |

| Std | 3.3109E + 01 | 3.7102E + 01 | 2.4897E + 01 | 4.1900E + 01 | 4.5952E + 01 | 4.1699E + 01 | |

(ii) Sensitivity in relation to T_Branch and T_Nmority in Level 2. T_Branch and T_Nmority play vital roles in the population varying process, and there are critical correlations between them; thus, these two parameters are analyzed together. In this experiment, population number M is fixed to 8, and the values of T_Branch are varied as 5, 10, and 15 while the relevant T_Nmority is selected to be 0 or 5. From Table 5, it is clearly visible that the HARFO obtains best computation results on most test functions including f 11, f 13, f 14, and f 15 when T_Branch/T_Nmority are set as 10/5. Therefore, the optimal configuration of T_Branch/T_Nmority is 10/5 as general usage of the algorithm.

Table 5.

Results obtained by HARFO with different T_Branch and T_Nmority.

| T_Branch/T_Nmority | 5/0 | 10/0 | 15/0 | 5/5 | 10/5 | 15/5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| f 11 | Mean | 2.9494E + 01 | 2.9835E − 01 | 1.7934E + 01 | 2.0332E + 01 | 1.6815E + 01 | 3.0914E + 02 |

| Std | 6.0931E − 01 | 3.9945 | 6.1453E − 01 | 5.0094E − 01 | 4.0143E − 01 | 9.0093 | |

|

| |||||||

| f 12 | Mean | 4.5534E + 02 | 2.4346E + 03 | 8.6729E − 01 | 2.4621E + 02 | 4.0316E + 01 | 3.4344E + 01 |

| Std | 2.3424E + 02 | 1.5529E + 02 | 3.4031E + 01 | 1.6436E + 02 | 6.8932E + 01 | 5.6987 | |

|

| |||||||

| f 13 | Mean | 3.0352E + 01 | 6.3321E + 01 | 3.6239E + 01 | 3.1234E + 02 | 3.0629E + 01 | 1.0342E + 02 |

| Std | 4.0945E + 01 | 8.0345E + 01 | 2.9023E + 01 | 9.0945E + 01 | 1.0552E + 01 | 9.0934E + 01 | |

|

| |||||||

| f 14 | Mean | 4.0333E + 01 | 1.4452E + 02 | 4.8845E + 02 | 2.0340E + 02 | 2.3000E + 01 | 2.4136E + 00 |

| Std | 7.9834 | 6.8554 | 5.2231E + 01 | 2.4442E + 01 | 5.9403E − 01 | 5.9453E − 01 | |

|

| |||||||

| f 15 | Mean | 1.0934E + 02 | 5.5423E + 01 | 4.9000E + 01 | 2.2454E + 02 | 4.9000E + 01 | 1.0043E + 02 |

| Std | 4.2213E + 02 | 4.7775E + 01 | 6.0003E + 01 | 8.8896E + 01 | 2.0387E + 01 | 3.2009E + 01 | |

As the summary of this section, all suggested values of the control parameters can be listed as follows: M = 8, T_Branch = 10, and T_Nmority = 5. These values are determined by experiments where the correlative T_Branch and T_Nmority in level 2 are taken into consideration together, and the third one in level 1 is varied over an interval with a step size.

3.4. Computational Results

(i) Comparative Results on 30-Dimensional Case. HARFO is compared with ABC, PSO, and CCGA on ten 30-dimensional benchmarks f 1–f 10. On each benchmark, these algorithms are independently implemented 20 times and terminated when the number of function evaluations reaches 100,000 for each run. The statistical results in terms of mean and standard deviation of each benchmark over 20 runs are calculated and shown in Table 6. As revealed from experimental results in Table 6, HARFO generally shows relative outperformance for solving most test benchmarks, compared to CCGA and ABC, which obtain the second and third best rankings, respectively.

Table 6.

Comparison of results with 30 dimensions obtained by each algorithm (f(x) − f(x ∗)).

| Func. | HARFO | ABC | ARFO | PSO | CCGA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| f 1 | Mean | 4.2817E − 13 | 1.3230E − 20 | 8.4537E − 03 | 6.4050E − 01 | 1.2942E − 20 |

| Std | 5.8831E − 13 | 4.3300E − 20 | 6.6176E − 03 | 2.2735E − 01 | 4.2357E − 20 | |

|

| ||||||

| f 2 | Mean | 7.2733E − 01 | 3.9681E + 00 | 6.9380E + 01 | 2.6402E + 02 | 3.8817E + 00 |

| Std | 1.5903E + 00 | 3.7709E + 00 | 1.3271E + 00 | 1.4057E + 02 | 3.6888 | |

|

| ||||||

| f 3 | Mean | 2.1575E − 13 | 4.9539E + 01 | 7.5788E + 01 | 1.3201E + 02 | 4.8976E + 01 |

| Std | 1.2233E − 12 | 1.3063E + 01 | 1.1519E + 00 | 3.7770E + 02 | 1.2903E + 01 | |

|

| ||||||

| f 4 | Mean | 7.6514E − 04 | 2.8590E − 04 | 4.4610E + 03 | 2.9702E + 02 | 2.8094E − 04 |

| Std | 6.3836E − 04 | 2.7604E − 04 | 2.2428E + 02 | 2.1757E + 02 | 1.5404E − 04 | |

|

| ||||||

| f 5 | Mean | 5.0157E − 03 | 8.3921E − 02 | 9.2917E − 01 | 3.9481E + 00 | 8.2891E − 02 |

| Std | 4.9156E − 03 | 7.3446E − 02 | 2.8713E − 01 | 2.6640E − 03 | 7.2544E − 02 | |

|

| ||||||

| f 6 | Mean | 4.0543E − 14 | 7.5624E − 14 | 6.3095E + 02 | 9.4363E + 01 | 7.4696E − 14 |

| Std | 3.4998E − 14 | 3.0806E − 14 | 7.8376E + 02 | 3.9237E + 01 | 6.6428E − 14 | |

|

| ||||||

| f 7 | Mean | 8.4784E + 00 | 2.4324E + 01 | 1.4680E + 00 | 7.0365E + 06 | 2.4025E + 01 |

| Std | 1.2762E + 00 | 7.1995E + 01 | 2.0352E + 00 | 2.3168E + 07 | 7.1111E + 01 | |

|

| ||||||

| f 8 | Mean | 1.9573E + 02 | 9.0699E + 02 | 1.9471E + 02 | 2.0902E + 04 | 8.9575E + 02 |

| Std | 4.6811E + 02 | 5.8412E + 02 | 1.5947E + 01 | 4.8404E + 03 | 5.7698E + 02 | |

|

| ||||||

| f 9 | Mean | 1.6015E + 03 | 2.0949E + 03 | 5.2497E + 03 | 2.5180E + 03 | 2.0664E + 03 |

| Std | 6.9952E − 01 | 7.4802E − 13 | 5.2374E + 02 | 3.8381E + 02 | 7.6612E − 13 | |

|

| ||||||

| f 10 | Mean | 6.8062E + 00 | 5.9028E + 01 | 3.4875E + 02 | 6.6128E + 01 | 5.8311E + 01 |

| Std | 6.4614E − 01 | 1.7745E − 01 | 6.5806E + 01 | 5.7449E + 00 | 1.7554E − 01 | |

On f 1, HARFO, CCGA, and ABC perform close to each other, relatively better than other algorithms. Specifically, CCGA does better than ABC, followed by CCGA. On f 2, ARFO remarkably outperforms others as well as CCGA and ABC obtain close results, significantly better than other algorithms. For complex multimodal variable-separable f 3, variable-separable f 4, and nonseparable f 5, HARFO performs slightly better than CCGA and ABC, furthermore significantly better than other algorithms. Particularly, on f 3 and f 5, the search performance order can be shown apparently as HARFO > CCGA > ABC > ARFO > PSO. On f 6–f 10, which are more complex shifted and rotated benchmarks, HARFO can obtain best performance in terms of mean, maximum, and minimum on most of five benchmarks including f 6, f 8, f 9, and f 10 and ARFO also outperforms other algorithms on f 7. Apparently, HARFO shows significant improvement over other algorithms, especially ARFO.

(ii) Comparative Results on 100-Dimensional Case. In order to assess the scalability of our proposed algorithm, which is crucial for its applicability to real-world high-dimensional problems, the test benchmarks are extended to 100-dimensional problems as high-dimensional cases. The experimental results are given in Table 7. From Table 7, it is observed that HARFO significantly outperforms other algorithms almost all test functions except for f 2 and f 7. Particularly, compared to other algorithms, the solution accuracy of HARFO on shifted and rotated f 5, f 9, and f 10 is increased by one order of magnitude. From the distinct difference between dimension = 20 and 100 results, it is clearly observed that with dimensionality increasing, the proposed algorithm exhibits its persistence and performs better.

Table 7.

Comparison of results with 100 dimensions obtained by each algorithm (f(x) − f(x ∗)).

| Func. | HARFO | ABC | ARFO | PSO | CCGA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| f 1 | Mean | 1.2867E − 03 | 2.5048E − 03 | 4.3104E − 02 | 4.5449E + 02 | 1.2558E − 02 |

| Std | 6.2167E − 03 | 5.0736E − 03 | 7.8429E − 03 | 1.1368E + 02 | 5.7436E − 03 | |

|

| ||||||

| f 2 | Mean | 2.3158E + 02 | 6.2667E + 02 | 6.0868E + 02 | 1.0874E + 04 | 9.8880E + 01 |

| Std | 2.9080E + 01 | 6.8733E + 02 | 3.3206E + 01 | 6.7649E + 04 | 3.2121E + 01 | |

|

| ||||||

| f 3 | Mean | 6.7884E + 02 | 1.4622E + 02 | 9.1064E + 02 | 5.6672E + 03 | 8.8089E + 02 |

| Std | 1.3927E + 02 | 1.8944E + 01 | 6.6473E + 01 | 7.2860E + 02 | 6.7302E + 01 | |

|

| ||||||

| f 4 | Mean | 1.7000E + 01 | 5.1011E + 02 | 1.7000E + 01 | 1.7000E + 01 | 1.8874E + 01 |

| Std | 4.0850E + 00 | 1.2089E + 02 | 2.3858E + 00 | 7.2467E + 00 | 2.6488E + 00 | |

|

| ||||||

| f 5 | Mean | 1.7451E − 01 | 5.4011E + 01 | 1.6357E + 01 | 1.5808E + 03 | 1.7160E − 01 |

| Std | 2.1547E − 01 | 2.7978E + 01 | 4.4982E + 00 | 3.2400E + 02 | 1.9940E − 01 | |

|

| ||||||

| f 6 | Mean | 6.4416E + 03 | 7.2900E + 04 | 9.8642E + 03 | 2.3474E + 05 | 9.5026E + 03 |

| Std | 1.1540E + 03 | 2.5311E + 03 | 1.0969E + 03 | 4.0396E + 04 | 1.1567E + 03 | |

|

| ||||||

| f 7 | Mean | 3.3781E + 10 | 2.8028E + 10 | 1.1095E + 09 | 6.8711E + 09 | 1.1688E + 09 |

| Std | 1.1606E + 10 | 8.0320E + 09 | 4.6126E + 08 | 1.9879E + 08 | 4.4435E + 08 | |

|

| ||||||

| f 8 | Mean | 1.2057E + 05 | 3.5396E + 05 | 1.2118E + 05 | 4.5362E + 05 | 1.3464E + 05 |

| Std | 1.7588E + 04 | 9.1560E + 04 | 4.1061E + 03 | 3.1074E + 04 | 4.5623E + 03 | |

|

| ||||||

| f 9 | Mean | 1.5149E + 03 | 1.8168E + 04 | 3.5279E + 04 | 2.8477E + 04 | 3.9199E + 04 |

| Std | 1.0312E + 02 | 2.7420E + 03 | 1.3535E + 03 | 8.9127E + 02 | 1.5039E + 03 | |

|

| ||||||

| f 10 | Mean | 2.2175E + 02 | 6.5384E + 03 | 1.1434E + 03 | 1.8442E + 03 | 1.2704E + 03 |

| Std | 3.7382E + 00 | 3.6678E + 00 | 1.2423E + 02 | 2.2994E + 02 | 1.3803E + 02 | |

Finally, the performance improvement obtained by our proposed algorithm can be generally explained: when other algorithms are trapped in the local optima, the HARFO can utilize the root-to-root communication mechanism to escape. By employing the hierarchical multipopulation coevolution, the complex task is decomposed into smaller-scale subproblems.

(iii) Comparative Results on 30-Dimensional CEC 2014 Case. Computation results in terms of means and stand deviations of the 20 runs obtained by six algorithms on ten 30-dimensional CEC 2014 benchmarks are given in Table 8, within which the best results among those algorithms are highlighted. From Table 8, the proposed HARFO performs significantly superior to its counterparts including CCGA and ABC on most of test benchmarks. Specifically, HARFO can do better than CCGA on f 11, f 12, f 14, f 16, f 17, f 19, and f 20, followed by ABC and ARFO, PSO cannot obtain competitive results. On f 13 and f 15, ABC and CCGA perform significantly better than ARFO and slightly better than HARFO. PSO also obtains best result on f 18. Furthermore, we can observe that although the shifted and rotated CEC 2014 benchmarks become more difficult to be handled compared with their classical counterparts and the computation results are not as satisfactory as those in the classical benchmarks, HARFO still performs more powerful than other algorithms on most test cases. This essentially indicates that HARFO has greater potential to cope with more complex problems.

Table 8.

Comparison of results with 30 dimensions obtained by each algorithm (f(x) − f(x ∗)).

| Func. | HARFO | ABC | ARFO | PSO | CCGA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| f 11 | Mean | 1.6815E + 01 | 1.9799E + 07 | 1.2573E + 07 | 2.9358E + 08 | 1.9563E + 02 |

| Std | 3.9994E − 01 | 6.7129E + 06 | 1.0473E + 07 | 2.1609E + 08 | 6.6330E + 02 | |

|

| ||||||

| f 12 | Mean | 3.1528E + 01 | 7.5904E + 02 | 1.0104E + 08 | 7.0153E + 08 | 7.5001E + 02 |

| Std | 2.4023E + 01 | 7.5572E + 02 | 2.3503E + 08 | 2.8266E + 08 | 7.4673E + 02 | |

|

| ||||||

| f 13 | Mean | 2.8969E + 01 | 1.3000E + 01 | 1.5265E + 02 | 4.5742E + 02 | 1.3000E + 01 |

| Std | 1.5290E + 00 | 2.5348E + 01 | 5.0791E + 01 | 1.5825E + 02 | 2.8136E + 01 | |

|

| ||||||

| f 14 | Mean | 2.2457E + 01 | 2.4494E + 01 | 2.4296E + 01 | 2.5464E + 01 | 2.7188E + 01 |

| Std | 4.8265E − 01 | 4.8600E − 02 | 1.2623E − 02 | 7.6957E − 02 | 5.3946E − 02 | |

|

| ||||||

| f 15 | Mean | 4.2697E + 01 | 1.9000E + 01 | 3.6291E + 01 | 5.0531E + 01 | 1.9000E + 01 |

| Std | 8.1373E + 00 | 1.7665E + 00 | 3.1039E + 00 | 2.2499E + 00 | 1.0608E + 00 | |

|

| ||||||

| f 16 | Mean | 3.1060E − 03 | 1.3200E − 03 | 5.6546E + 00 | 1.2402E + 02 | 1.4652E − 03 |

| Std | 1.5530E − 03 | 3.8400E − 03 | 7.0040E + 00 | 3.0668E + 01 | 4.4330E − 03 | |

|

| ||||||

| f 17 | Mean | 6.1585E − 06 | 5.1208E + 02 | 1.5884E + 02 | 3.1284E + 02 | 5.9117E + 02 |

| Std | 3.3153E − 05 | 1.1126E + 02 | 3.0743E + 01 | 4.1798E + 01 | 1.2844E + 02 | |

|

| ||||||

| f 18 | Mean | 2.1913E + 03 | 6.1602E + 06 | 3.5613E + 05 | 2.0148E + 03 | 7.1116E + 06 |

| Std | 4.7034E + 02 | 3.4051E + 06 | 7.1417E + 05 | 3.4323E + 02 | 3.9310E + 06 | |

|

| ||||||

| f 19 | Mean | 4.7272E + 02 | 1.6622E + 04 | 8.5742E + 02 | 7.3078E + 06 | 1.5327E + 04 |

| Std | 2.2216E + 02 | 1.4328E + 03 | 1.2094E + 02 | 5.5582E + 06 | 1.3212E + 03 | |

|

| ||||||

| f 20 | Mean | 2.4618E + 02 | 2.7362E + 02 | 2.9471E + 02 | 4.7931E + 02 | 2.5231E + 02 |

| Std | 1.2685E + 01 | 1.6578E + 02 | 9.1791E + 02 | 2.9374E + 01 | 1.5287E + 02 | |

4. Real-World Application for Image Segmentation

4.1. Otsu Criterion

The well-known Otsu criterion has been widely adopted to determine the optimal thresholds with desired characteristics through computing between-class variance [7, 8]. The original procedures of Otsu can be listed as below: at the beginning, a given image consisting of N pixels of gray levels falling into the range [0, L − 1] is taken into consideration. h(i) donates the pixel number of gray-level i and P(i) represents the probability of gray-level i.

Then, we have

| (10) |

Hypothesize that M − 1 thresholds, namely, {t 1, t 2, …, t M−1}, are required to segment the given image into M classes: C 1 for [0,…, 1], C 2 for [t 1 + 1,…, 1],…, C M for [t M−1,…, L], the optimal thresholds {t 1 ∗, t 2 ∗, …, t M−1 ∗} selected by Otsu are described as

| (11) |

where

| (12) |

Generally, (11) is employed as the fitness function for heuristic methods based procedure to be optimized. A close look into this equation will show that it is very similar to the expression for uniformity measure [40–43].

4.2. Experiment Setup

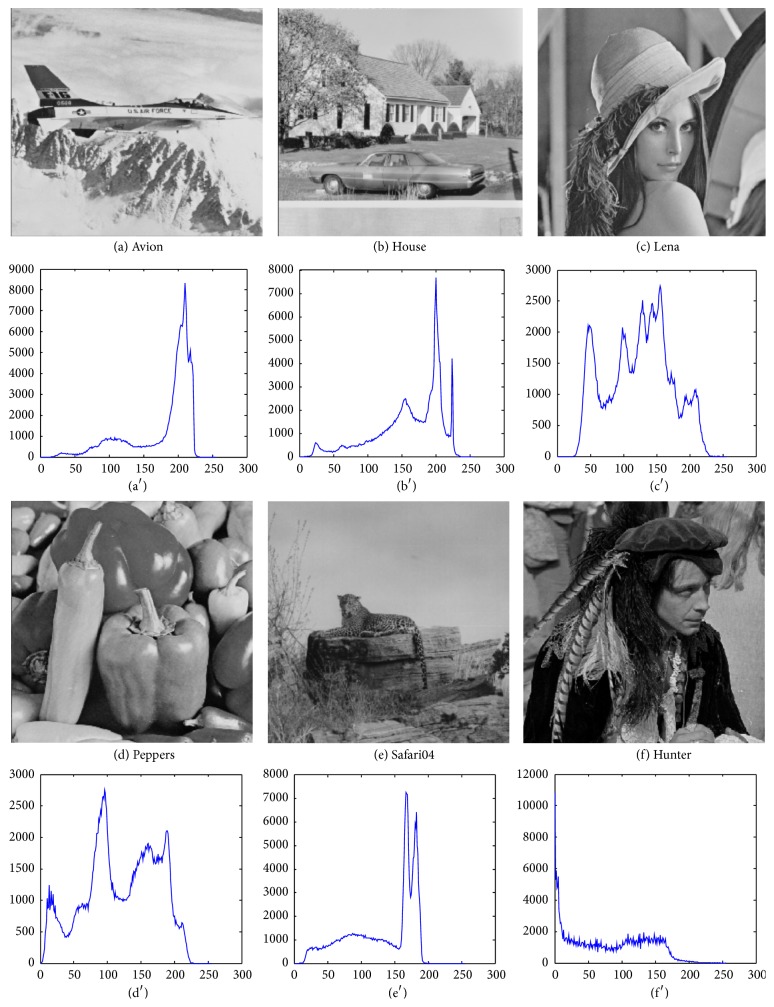

The image segmentation experiments by HARFO are conducted on a set of image datasets. These datasets consist of a variety of standard tested images widely employed in previous studies [42–47], including avion.ppm, house.ppm, lena.ppm, peppers.ppm, safari04.ppm, and hunter.pgm with pixels size of 512∗512 (available at http://decsai.ugr.es/cvg/dbimagenes/). Several state-of-the-art EA algorithms are selected for comprehensive comparison, namely, HARFO, ABC [20], ARFO [22], CCGA [39], and IDPSO [12]. Particularly, the IDPSO is an existing enhanced PSO variant with intermediate disturbance searching strategy recently proposed in [12] for image segmentation, which has gained satisfactory image segmentation r results. We will directly compare HARFO with existing computation results (i.e., for lena, peppers, and hunter) of IDPSO which have been reported in [12]. The parameters of HARFO, ABC, ARFO, PSO, and CCGA follow the optimal settings in Section 3.2. And the parameters of IDPSO are set the same as its original literature [12]. In this test, the proposed algorithm is to maximize the objective fitness within less computation time. The thresholds numbers M − 1 are set to 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, and 9. And Figure 4 presents test images and their histograms.

Figure 4.

Test images and their histograms.

4.3. Experimental Results and Analysis

Case 1 (segmentation results with M − 1 = 2,3, 4). —

Table 9 lists the objective values and mean computational time found by pure Otsu, which are partly reported in [12]. In practical real-time application, we hope that algorithms can keep a suitable balance of running time and high accuracy [48]. As shown in Table 9, due to the exhaustive search feature, Otsu needs to consume too long CPU time while achieving a satisfactory optimal thresholding. It can be seen from Table 10 that the proposed HARFO provides generally close results in terms of objective values and standard deviation compared with ABC and ARFO on some test cases, such as avion and lena. On lena, IDPSO and CCGA perform similarly, still a little worse than HARFO. At the same time considering the relevant results form Table 9, the proposed HARFO algorithm consumes less CPU time than its counterparts, which means that HARFO shows better efficiency. Compared with other algorithms, the HARFO has coevolution mechanism to perform better global search in higher-dimensional space.

Table 9.

Objective values and thresholds by the Otsu method.

| Image | M − 1 = 2 | M − 1 = 3 | M − 1 = 4 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Objective values | Optimal thresholds | Objective values | Optimal thresholds | Objective values | Optimal thresholds | |

| Avion | 3.493E + 3 | 113, 173 | 3.13E + 4 | 93, 145, 191 | 3.45E + 4 | 84, 129, 172, 203 |

| House | 2.24E + 3 | 107, 173 | 2.42E + 4 | 84, 137, 181 | 2.86E + 4 | 71, 118, 153, 186 |

| Lena | 9.34E + 3 | 134, 165, | 1.13E + 4 | 121, 151, 176 | 1.26E + 4 | 111, 140, 158, 180 |

| Peppers | 9.35E + 3 | 134, 176 | 1.13E + 4 | 113, 158, 184 | 1.25E + 4 | 103, 140, 167, 189 |

| Safari04 | 2.53E + 3 | 82, 141 | 2.33E + 4 | 65, 107, 151 | 2.43E + 4 | 55, 88, 120, 156 |

| Hunter | 5.45E + 3 | 102, 146 | 5.45E + 3 | 86, 129, 155 | 9.75E + 3 | 69, 112, 137, 158 |

| Mean CPU time | 2.1472 | 175.776 | 7945.325 | |||

Table 10.

Objective values and standard deviation by heuristic methods on Otsu algorithm.

| Image | M − 1 | Objective values (standard deviation) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HARFO | ABC | ARFO | CCGA | IDPSO | ||

| Avion | 2 | 4.3909E + 04 | 3.8752E + 04 | 3.8870E + 04 | 3.902E + 04 | 3.948E + 04 |

| 3.8166E − 01 | 8.7275E − 12 | 1.8550E − 02 | 8.642E − 02 | 1.594E − 01 | ||

| 3 | 4.4003E + 04 | 3.8839E + 04 | 3.8948E + 04 | 4.034E + 04 | 4.013E + 04 | |

| 2.0072E − 01 | 2.1530E − 01 | 1.2917E − 01 | 4.442E − 01 | 5.238E − 01 | ||

| 4 | 4.4031E + 04 | 3.8889E + 04 | 4.4001E + 04 | 4.441E + 04 | 4.111E + 04 | |

| 5.9884E − 01 | 5.3222E − 01 | 9.4322E − 01 | 1.542E − 01 | 2.442E − 01 | ||

|

| ||||||

| House | 2 | 3.6206E + 04 | 3.1941E + 04 | 3.2069E + 04 | 3.423E + 04 | 3.551E + 04 |

| 3.7387E − 02 | 0.0000E + 00 | 7.0560E − 02 | 2.194E − 01 | 5.422E − 04 | ||

| 3 | 3.6371E + 04 | 3.2082E + 04 | 3.2209E + 04 | 3.441E + 04 | 3.532E + 04 | |

| 3.5218E − 02 | 4.2787E − 02 | 2.2613E − 01 | 5.213E − 01 | 7.522E − 03 | ||

| 4 | 3.6430E + 04 | 3.2137E + 04 | 3.2332E + 04 | 3.424E + 04 | 3.575E + 04 | |

| 1.0542E + 00 | 5.4974E − 01 | 7.3052E − 01 | 2.113E + 00 | 5.094E − 02 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Lena | 2 | 2.2663E + 04 | 1.3928E + 04 | 1.0034E + 04 | 2.132E + 03 | 9.3449E3 |

| 1.0934E − 02 | 5.0944E − 12 | 5.4093E − 02 | 2.422E − 01 | 5.46E − 12 | ||

| 3 | 2.4983E + 04 | 2.0233E + 04 | 2.1033E + 04 | 2.142E + 04 | 1.1334E4 | |

| 8.0934E − 03 | 7.42343E − 02 | 4.4421E − 01 | 2.499E − 02 | 9.095E − 12 | ||

| 4 | 2.2742E + 04 | 2.0003E + 04 | 1.9999E + 04 | 2.042E + 04 | 1.2558E4 | |

| 2.6544E − 01 | 6.42245E − 01 | 5.4226 | 5.453 | 4.336E − 1 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Peppers | 2 | 1.0340E + 04 | 1.9533E + 04 | 2.0344E + 04 | 9.924E + 03 | 9.3515E3 |

| 4.5333E − 12 | 5.34337E − 12 | 7.5652E − 02 | 5.424E − 01 | 1.27E − 11 | ||

| 3 | 1.1322E + 04 | 1.0125E + 04 | 1.1333E + 04 | 1.153E + 04 | 1.1269E4 | |

| 1.4422E + 00 | 2.5566E − 02 | 2.4223E − 01 | 5.5301 | 5.46E − 12 | ||

| 4 | 1.9834E + 04 | 1.9593E + 04 | 1.9818E + 04 | 1.993E + 04 | 1.2525E4 | |

| 9.0452E − 11 | 9.7863E − 02 | 1.9887 | 4.522E − 01 | 5.45E − 12 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Safari04 | 2 | 2.5866E + 04 | 2.2766E + 04 | 2.2984E + 04 | 2.414E + 04 | 2.363E + 04 |

| 5.6183E − 01 | 0.0000E + 00 | 4.7684E − 02 | 5.252E − 01 | 5.414E − 02 | ||

| 3 | 2.5954E + 04 | 2.2865E + 04 | 2.3015E + 04 | 2.422E + 04 | 2.309E + 04 | |

| 9.5100E − 01 | 3.5163E − 02 | 2.0405E − 01 | 7.532E − 01 | 5.522E − 01 | ||

| 4 | 2.6005E + 04 | 2.2903E + 04 | 2.3122E + 04 | 2.443E + 04 | 2.442E + 04 | |

| 7.0754E − 01 | 1.0771E + 00 | 1.8869E − 01 | 2.0934 | 5.720E − 02 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Hunter | 2 | 2.2311E + 04 | 1.0378E + 04 | 1.0389E + 04 | 5.042E + 02 | 5.4491E3 |

| 0 | 0 | 2.0462E − 01 | 5.642E − 01 | 0 | ||

| 3 | 6.5233E + 03 | 3.0422E + 03 | 6.5222E + 03 | 6.043E + 03 | 6.4260E3 | |

| 2.4122 | 8.4544 | 5.4223E − 01 | 5.3252 | 1.774E − 1 | ||

| 4 | 6.4522E + 04 | 1.1444E + 04 | 6.8632E + 03 | 1.214E + 04 | 6.9721E3 | |

| 1.0222 | 5.7733 | 5.0530 | 3.534 | 1.4463 | ||

Case 2 (segmentation results with M − 1 = 5,7, 9). —

Table 11 gives computational results with M − 1 = 5, 7, and 9 in terms of average fitness and standard deviation of each algorithm. From Table 11, it is clearly observed that there are statistically significant differences between Cases 1 and 2 based on these segmentation algorithms, in aspects of both efficiency and stability. Due to the hybrid optimal strategies, HARFO exhibits obviously promising performance on this higher-dimensional segmentation case with M − 1 = 5, 7, and 9. Among these methods except HARFO, the ABC method also possesses relative powerful exploration ability due to usage of the scout bees operation. However, as shown in Table 11, as the number of segmentation thresholds increases, the results in terms of fitness values found by HARFO are significantly better than that of other methods, including the ABC algorithm. Generally, it can be concluded that HARFO performs better than other algorithms in this higher-dimensional scenario.

Table 11.

Objective value and standard deviation by the compared population based methods on Otsu algorithm.

| Image | M − 1 | Objective values (standard deviation) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HARFO | ABC | ARFO | CCGA | IDPSO | ||

| Avion | 5 | 4.2940E + 04 | 4.0947E + 04 | 4.2721E + 04 | 4.266E + 04 | 4.165E + 04 |

| 6.6839E − 02 | 1.5094E + 00 | 1.2493E + 00 | 3.133E − 02 | 4.9845E − 02 | ||

| 7 | 4.2852E + 04 | 4.0972E + 04 | 4.2735E + 04 | 4.266E + 04 | 4.243E + 04 | |

| 3.0811E − 02 | 3.8286E + 00 | 1.6504E + 00 | 4.531E − 01 | 5.325E − 01 | ||

| 9 | 4.2857E + 04 | 4.0986E + 04 | 4.2639E + 04 | 4.275E + 04 | 4.293E + 04 | |

| 1.3309E − 01 | 2.6222E + 00 | 5.4868E − 01 | 2.853E − 01 | 5.535E − 01 | ||

|

| ||||||

| House | 5 | 3.5543E + 04 | 3.3854E + 04 | 3.5364E + 04 | 3.443E + 04 | 3.468E + 04 |

| 5.3886E − 01 | 1.8866E + 00 | 5.8096E − 01 | 2.284E − 01 | 8.653E − 02 | ||

| 7 | 3.5558E + 04 | 3.3895E + 04 | 3.5360E + 04 | 3.512E + 04 | 3.574E + 04 | |

| 1.0541E − 01 | 5.4665E + 00 | 1.7216E + 00 | 5.543E − 01 | 5.524E − 01 | ||

| 9 | 3.5610E + 04 | 3.3919E + 04 | 3.5263E + 04 | 3.521E + 04 | 3.341E + 04 | |

| 1.4416E − 01 | 3.8422E + 00 | 1.4566E + 00 | 2.842 | 6.751E − 01 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Lena | 5 | 1.2141E + 04 | 1.1077E + 04 | 1.1890E + 04 | 1.340E + 04 | 1.3399E4 |

| 1.1142E − 02 | 2.3456E + 00 | 6.9755E − 01 | 2.434E − 01 | 2.01E − 2 | ||

| 7 | 1.2232E + 04 | 1.1144E + 04 | 1.1942E + 04 | 1.135E + 04 | 1.4418E4 | |

| 1.2534E − 01 | 5.0432E + 00 | 8.9221E − 01 | 2.743 | 4.2087 | ||

| 9 | 1.2154E + 04 | 1.1424E + 04 | 1.2012E + 04 | 1.133E + 04 | 1.4984E4 | |

| 1.7543E − 01 | 3.8324E + 00 | 1.7423E + 00 | 3.326 | 6.457 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Peppers | 5 | 2.1900E + 04 | 2.0668E + 04 | 2.1587E + 04 | 2.202E + 04 | 1.3366E4 |

| 5.0443E − 02 | 1.7541E + 00 | 2.0475E + 00 | 2.1408E − 01 | 5.019E − 1 | ||

| 7 | 2.1717E + 04 | 2.0710E + 04 | 2.1531E + 04 | 1.522E + 04 | 1.4293E4 | |

| 1.3917E − 01 | 2.8835E + 00 | 2.6158E + 00 | 2.244 | 1.1924E + 1 | ||

| 9 | 2.1743E + 04 | 2.0725E + 04 | 2.1645E + 04 | 1.662E + 04 | 1.4792E4 | |

| 2.3165E − 01 | 2.8313 | 2.3470 | 6.354 | 9.3027 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Safari04 | 5 | 2.5363E + 04 | 2.4130E + 04 | 2.5172E + 04 | 2.319E + 04 | 2.516E + 04 |

| 1.1934E − 01 | 6.1834E + 00 | 1.6155E + 00 | 1.542E − 01 | 2.526E + 00 | ||

| 7 | 2.5449E + 04 | 2.4154E + 04 | 2.5225E + 04 | 2.524E + 04 | 2.413E + 04 | |

| 1.3396E − 01 | 4.8186E + 00 | 1.2653E + 00 | 4.563E − 01 | 6.224E − 01 | ||

| 9 | 2.5472E + 04 | 2.4165E + 04 | 2.5062E + 04 | 2.401E + 04 | 2.446E + 04 | |

| 1.0982E − 01 | 1.9172E + 00 | 5.8804E − 01 | 2.536 | 5.514E − 01 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Hunter | 5 | 1.1723E + 04 | 1.1205E + 04 | 1.1614E + 04 | 1.113E + 04 | 7.350E3 |

| 9.4823E − 02 | 4.7343E + 00 | 1.6177E + 00 | 4.562E − 01 | 5.1693 | ||

| 7 | 1.1774E + 04 | 1.1242E + 04 | 1.1668E + 04 | 1.102E + 04 | 7.752E3 | |

| 2.0734E − 01 | 4.3856E + 00 | 1.8600E + 00 | 2.326 | 9.7143 | ||

| 9 | 1.1805E + 04 | 1.1260E + 04 | 1.1695E + 04 | 1.101E + 04 | 7.974E3 | |

| 1.5995E − 01 | 3.6223E + 00 | 4.0659E + 00 | 2.563 | 1.620E + 1 | ||

5. Conclusions

This paper proposes and develops a novel bionic optimization algorithm inspired by plant root growth mechanism to solve multilevel threshold image segmentation, namely, hybrid artificial root foraging optimizer (HARFO). Based on original single-colony ARFO, the potential of HARFO to improve the global search performance and keep diversity of population relies on the combination of the root-to-root communication and multipopulation cooperative mechanism. With root-to-root communication, information exchanging between individuals can be enhanced through different efficient topologies. With coevolution mechanism, the hierarchical spatial population driven by multipopulations is constructed to ensure that diversity of population is well kept.

The comparative experiments of HARFO in comparison with several classical population based algorithms are conducted on a set of 20-dimensional and 100-dimensional benchmarks. The experimental results validate the superiority of the proposed algorithm. Finally, the HARFO is employed to handle the image segmentation problems with multilevel threshold. Computational results achieved by this method on a suit of images dataset show that the proposed algorithm has significant potential to be a novel effective and efficient image processing approach. In our future work, we will focus on perfecting this novel optimization framework from the perspective of relevance theory.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grants nos. 61503373 and 61502318 and the Natural Science Foundation of Liaoning Province under Grants nos. 2015020002 and 2015020046.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Lim Y. K., Lee S. U. On the color image segmentation algorithm based on the thresholding and the fuzzy c-means techniques. Pattern Recognition. 1990;23(9):935–952. doi: 10.1016/0031-3203(90)90103-r. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kittler J., Illingworth J. Minimum error thresholding. Pattern Recognition. 1986;19(1):41–47. doi: 10.1016/0031-3203(86)90030-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pun T. Entropy threshold: a new approach. Computer Graphics and Image Processing. 1981;16(3):210–239. doi: 10.1016/0146-664x(81)90038-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pal N. R., Pal S. K. A review on image segmentation techniques. Pattern Recognition. 1993;26(9):1277–1294. doi: 10.1016/0031-3203(93)90135-j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Panda R., Agrawal S., Bhuyan S. Edge magnitude based multilevel thresholding using Cuckoo search technique. Expert Systems with Applications. 2013;40(18):7617–7628. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2013.07.060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Romero A., Cazorla M. Topological visual mapping in robotics. Cognitive Processing. 2012;13(supplement 1):S305–S308. doi: 10.1007/s10339-012-0502-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Otsu N. A threshold selection method from gray-level histograms. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics. 1979;9(1):62–66. doi: 10.1109/tsmc.1979.4310076. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kapur J. N., Sahoo P. K., Wong A. K. C. A new method for gray-level picture threshold using the entropy of the histogram. Computer Vision, Graphics, and Image Processing. 1985;29(3):273–285. doi: 10.1016/0734-189x(85)90125-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsai D.-M. A fast thresholding selection procedure for multimodal and unimodal histograms. Pattern Recognition Letters. 1995;16(6):653–666. doi: 10.1016/0167-8655(95)80011-H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhandari A. K., Kumar A., Singh G. K. Modified artificial bee colony based computationally efficient multilevel thresholding for satellite image segmentation using Kapur's, Otsu and Tsallis functions. Expert Systems with Applications. 2015;42(3):1573–1601. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2014.09.049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bouaziz A., Draa A., Chikhi S. Artificial bees for multilevel thresholding of iris images. Swarm and Evolutionary Computation. 2015;21:32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.swevo.2014.12.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gao H., Kwong S., Yang J., Cao J. Particle swarm optimization based on intermediate disturbance strategy algorithm and its application in multi-threshold image segmentation. Information Sciences. 2013;250:82–112. doi: 10.1016/j.ins.2013.07.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang P., Cao H., Luo S. An artificial ant colonies approach to medical image segmentation. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine. 2008;92(3):267–273. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2008.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ayala H. V. H., Santos F. M. D., Mariani V. C., Coelho L. D. S. Image thresholding segmentation based on a novel beta differential evolution approach. Expert Systems with Applications. 2015;42(4):2136–2142. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2014.09.043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sezgin M., Sankur B. Survey over image thresholding techniques and quantitative performance evaluation. Journal of Electronic Imaging. 2004;13(1):146–168. doi: 10.1117/1.1631315. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhandari A. K., Singh V. K., Kumar A., Singh G. K. Cuckoo search algorithm and wind driven optimization based study of satellite image segmentation for multilevel thresholding using Kapur's entropy. Expert Systems with Applications. 2014;41(7):3538–3560. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2013.10.059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sathya P. D., Kayalvizhi R. Modified bacterial foraging algorithm based multilevel thresholding for image segmentation. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence. 2011;24(4):595–615. doi: 10.1016/j.engappai.2010.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coello Coello C. A., Pulido G. T., Lechuga M. S. Handling multiple objectives with particle swarm optimization. IEEE Transactions on Evolutionary Computation. 2004;8(3):256–279. doi: 10.1109/tevc.2004.826067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bishopp A., Help H., El-Showk S., et al. A mutually inhibitory interaction between auxin and cytokinin specifies vascular pattern in roots. Current Biology. 2011;21(11):917–926. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karaboga D., Basturk B. On the performance of artificial bee colony (ABC) algorithm. Applied Soft Computing. 2008;8(1):687–697. doi: 10.1016/j.asoc.2007.05.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McNickle G. G., St Clair C. C., Cahill J. F., Jr. Focusing the metaphor: plant root foraging behaviour. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 2009;24(8):419–426. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ma L., Zhu Y., Liu Y., Tian L., Chen H. A novel bionic algorithm inspired by plant root foraging behaviors. Applied Soft Computing Journal. 2015;37:95–113. doi: 10.1016/j.asoc.2015.08.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ma L., Hu K., Zhu Y., Chen H. A hybrid artificial bee colony optimizer by combining with life-cycle, Powell's search and crossover. Applied Mathematics and Computation. 2015;252:133–154. doi: 10.1016/j.amc.2014.11.104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ma L., Hu K., Zhu Y., Chen H. Cooperative artificial bee colony algorithm for multi-objective RFID network planning. Journal of Network and Computer Applications. 2014;42:143–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jnca.2014.02.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang H., Inukai Y., Yamauchi A. Root development and nutrient uptake. Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences. 2006;25(3):279–301. doi: 10.1080/07352680600709917. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang Z., van Kleunen M., During H. J., Werger M. J. A. Root foraging increases performance of the clonal plant Potentilla reptans in heterogeneous nutrient environments. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058602.e58602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dannowski M., Block A. Fractal geometry and root system structures of heterogeneous plant communities. Plant and Soil. 2005;272(1-2):61–76. doi: 10.1007/s11104-004-3981-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kembel S. W., De Kroon H., Cahill J. F., Jr., Mommer L. Improving the scale and precision of hypotheses to explain root foraging ability. Annals of Botany. 2008;101(9):1295–1301. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcn044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kennedy J., Mendes R. Population structure and particle swarm performance. Proceedings of the Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC '02); May 2002; IEEE; pp. 1671–1676. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gleeson S. K., Fry J. E. Root proliferation and marginal patch value. Oikos. 1997;79(2):387–393. doi: 10.2307/3546023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kelly C. K. Resource choice in Cuscuta europaea. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1992;89(24):12194–12197. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.24.12194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Kroon H., Huber H., Stuefer J. F., van Groenendael J. M. A modular concept of phenotypic plasticity in plants. New Phytologist. 2005;166(1):73–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holland J. H. Adaptation in Natural and Artificial Systems: An Introductory Analysis with Applications to B, Control, and Artificial Intelligence. Ann Arbor, Mich, USA: University of Michigan Press; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ma L., Hu K., Zhu Y., Niu B., Chen H., He M. Discrete and continuous optimization based on hierarchical artificial bee colony optimizer. Journal of Applied Mathematics. 2014;2014:20. doi: 10.1155/2014/402616.402616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liang J., Qu B., Suganthan P. Zhengzhou University; 2013. Problem definitions and evaluation criteria for the CEC 2014 special session and competition on single objective real-parameter numerical optimization. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liang J. J., Qin A. K., Suganthan P. N., Baskar S. Comprehensive learning particle swarm optimizer for global optimization of multimodal functions. IEEE Transactions on Evolutionary Computation. 2006;10(3):281–295. doi: 10.1109/TEVC.2005.857610. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eberhart R. C., Kennedy J. New optimizer using particle swarm theory. Proceedings of the 1995 6th International Symposium on Micro Machine and Human Science; October 1995; Nagoya, Japan. pp. 39–43. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Corne D., Dorigo M., Glover F. New Ideas in Optimization. New York, NY, USA: McGraw-Hill; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Potter M. A., De Jong K. A. Cooperative coevolution: an architecture for evolving coadapted subcomponents. Evolutionary computation. 2000;8(1):1–29. doi: 10.1162/106365600568086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang H., Ni Q. A new method of moving asymptotes for large-scale unconstrained optimization. Applied Mathematics and Computation. 2008;203(1):62–71. doi: 10.1016/j.amc.2008.03.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tao W. B., Jin H., Liu L. M. Object segmentation using ant colony optimization algorithm and fuzzy entropy. Pattern Recognition Letters. 2007;28(7):788–796. doi: 10.1016/j.patrec.2006.11.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yin P.-Y. Multilevel minimum cross entropy threshold selection based on particle swarm optimization. Applied Mathematics and Computation. 2007;184(2):503–513. doi: 10.1016/j.amc.2006.06.057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cao L., Bao P., Shi Z. K. The strongest schema learning GA and its application to multilevel thresholding. Image and Vision Computing. 2008;26(5):716–724. doi: 10.1016/j.imavis.2007.08.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li X., Zhao Z., Cheng H. D. Fuzzy entropy threshold approach to breast cancer detection. Information Sciences-applications. 1995;4(1):49–56. doi: 10.1016/1069-0115(94)00019-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Horng M.-H., Liou R.-J. Multilevel minimum cross entropy threshold selection based on the firefly algorithm. Expert Systems with Applications. 2011;38(12):14805–14811. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2011.05.069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ma L., Staunton R. C. A modified fuzzy C-means image segmentation algorithm for use with uneven illumination patterns. Pattern Recognition. 2007;40(11):3005–3011. doi: 10.1016/j.patcog.2007.02.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liao P.-S., Chen T.-S., Chung P.-C. A fast algorithm for multilevel thresholding. Journal of Information Science & Engineering. 2001;17(5):713–727. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ma L., Zhu Y., Zhang D., Niu B. A hybrid approach to artificial bee colony algorithm. Neural Computing & Applications. 2016;27(2):387–409. doi: 10.1007/s00521-015-1851-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]