Abstract

While the use of computer-based communication, video recordings, and other “electronic” records is commonplace in clinical service settings and research, management of digital records can become a great burden from both practical and regulatory perspectives. Three types of challenges commonly present themselves: regulatory requirements; storage, transmission, and access; and analysis for clinical and research decision-making. Unfortunately, few practitioners and organizations are well enough informed to set necessary policies and procedures in an effective, comprehensive manner. The three challenges are addressed using a demonstrative example of policies and procedural guidelines from an applied perspective, maintaining the unique emphasis behavior analysts place upon quantitative analysis. Specifically, we provide a brief review of federal requirements relevant to the use of video and electronic records in the USA; non-jargon pragmatic solutions to managing and storing video and electronic records; and last, specific methodologies to facilitate extraction of quantitative information in a cost-effective manner.

Keywords: Technology, Electronic records, HIPAA, Video, Systems management

The hallmark of applied behavior analysis is the systematic collection and analysis of objective behavior data. Unfortunately, the greatest challenge faced by practitioners and human service agencies is the systematic collection, storage, and ongoing management of such data. The challenges faced are both ethical and practical. The Behavior Analyst Certification Board (BACB)’s Guidelines for Responsible Conduct of Behavior Analysts (July 2010) outlines several practitioner responsibilities in the creation, storage, access, transfer, and disposal of client/research participant records (see Guidelines 2.08 maintaining records and 2.12 records and data). Behavior analysts are tasked with developing an effective system that both meets these requirements and provides an efficient means to access and analyze client information to inform treatment. Such efforts are further bound by US federal, state, and institutional regulations.1 Not surprisingly, many behavior analysts use technology in their daily service activities. Significant conflict, however, can exist between the use of technology and safeguarding sensitive records, both with respect to professional guidelines and applicable regulation.

Access to technology has increased exponentially over the last several decades. The USA has seen a 67 % increase in household computer use between 1984 and 2011, and more than half of the US population owned a smartphone in 2013 (File 2013; Rogowsky 2013). This personalization of technology has permitted behavior analysts to move toward less burdensome data collection methods, including real-time video and observational recording on laptops, tablets, and cell phones. Mobile devices have also changed the portability of video in ways that go far beyond the days of camcorders and other portable recording devices. Video can now be sent via email or text message and also uploaded to sharing services such as YouTube™ with the click of a button, after being recorded or as a streaming file (i.e., during recording). Whiting and Dixon (2012) show just this level of versatility in their recent manuscript detailing the creation of an iPhone app for data collection with an “Email Data” button clearly displayed in their programming figures. Many commercially available apps have similar or more advanced sharing capabilities that go far beyond data collection and simple export. Clearly, these conveniences, quite literally at our fingertips, present great potentiality for promoting service access and streamlining service delivery. Expanded professional consultation opportunities are also now available since providers are not limited by physical proximity to resources. Further, the enormous storage capacities of even highly portable laptops, tablets, and smartphones allow for storing extensive records of various types on large numbers of clients. However, such conveniences also come with substantial risk. It is important to emphasize that compliance with federal and state regulations applies to individual behavior analysts as well as large agencies. The standards for compliance are the same whether one is self-employed or employed in an organization. And as is always the case in issues of ethical conduct and legal/regulatory compliance, individual behavior analysts cannot simply defer to their employer, supervisor, or larger organization on such matters, but must be able to confirm proper procedures are in place.

US Regulatory Parameters

HIPAA

One area of concern involves maintaining the security and confidentiality of client records and video recordings for applied purposes, as well as protection of research participants who have the dual status of a ‘protected’ group or ‘vulnerable’ population. The most pertinent federal regulations come from the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA). Examples of health care providers required to comply with HIPAA include individual providers (e.g., physicians, psychologists, dentists, etc.), agencies or clinics, and pharmacies. Added to the list are behavior analysts within the first two categories of health care providers, if serving as practitioners or administering programs that provide services and accept third party payment that then results in transmission of protected health information (PHI). Insurance reform efforts, including the enactment of the Affordable Care Act, will further broaden access to behavioral health services. As insurance reimbursement becomes the norm rather than the exception, behavior analysts are more likely to be classified as health care providers, and their clients as health care consumers, under HIPAA. Even if the current activities of an individual or agency do not fall under HIPAA regulation, it is strongly recommended that the same standards are adhered to as it is the generally accepted standard of protection.

HIPAA’s Privacy Rule (45 CFR Part 160 and Subparts A and E of Part 164) requires health care providers (broadly defined) to ensure the privacy of protected health information (PHI) and provides guidance as to what can be used and disclosed to various parties, including the patient’s right to their records. Readers are referred to Table 1 for a listing of PHI under HIPAA.

Table 1.

Comparison of HIPAA and FERPA information release parameters

| HIPAA | FERPA | |

|---|---|---|

| Information type | PHI | Protected record |

| Name | X | Xa |

| Address | Xb | Xa |

| Dates (except year) | Xc | Xa |

| Telephone/fax | X | Xa |

| X | ||

| Social security numbers | X | |

| Medical record numbers | X | |

| Health plan beneficiary numbers | X | |

| Account numbers | X | |

| Certificate and license numbers | X | |

| Vehicle identifiers and serial numbers | Xd | |

| Device identifiers and serial numbers | X | |

| URL and IP addresses | X | |

| Biometric identifiers | Xe | |

| Full photographic images/comparable images | X | |

| Other identifying information | Xf | X |

| Honors and awards | Xa | |

| Coursework/comments/discussions/grades | X |

Note. PHI stands for protected health information as defined by HIPAA that cannot be released without the permission. URL stands for uniform resource locator and is also known as a web address. IP address stands for Internet protocol address and is a numerical label assigned to a device, such as a computer or printer, using a network

a“Directory information” permitted for release, but a parent or a student aging 18 or older must be informed in sufficient time to refuse. The student’s educational record is otherwise protected against release without consent except in the instances of audit, school official inquiry, financial aid, transition of student to a new school, accreditation, or in relation to legal and health/safety orders

bAll geographic subdivisions smaller than a state, including street address, city, county, precinct, zip code, and their equivalent geocodes, except for the initial three digits of a zip code

cFor dates directly related to an individual, including birth date, admission or service date, discharge date, date of death; and all ages over 89 and all elements of dates (including year) indicative of such age, except that such ages and elements may be aggregated into a single category of age 90 or older

dIncludes license plate numbers

eSuch as fingerprints or voiceprints

fAny other unique identifying number, characteristic, or code, except as permitted by an assigned code or other means of record identification to allow information de-identified under this section to be reidentified by the covered entity that is not derived from some means of prohibited identifying information

HIPAA’s Security Rule (45 CFR Part 160 and Subparts A and C of Part 164) applies only to “information in electronic form” and specifies that providers must apply “reasonable and appropriate administrative, technical, and physical safeguards” in storage and sharing of electronic information. Exact parameters are not specified in order to allow providers to set safeguards that are appropriate for their agency size, function, and needs. Although most behavior analysts would prefer to have detailed instructions and guidelines to ensure compliance, the application of HIPAA regulations is broad. Some level of flexibility is needed for various institutions to develop necessary security parameters while still facilitating communication to ensure a high quality of care (i.e., procedures that work for an individual practitioner would not be appropriate for a national service organization). Thus, a detailed task analysis with respect to compliance is neither possible nor even permitted by HIPAA regulation as it requires a process of compliance, not simply a series of steps, procedures, and documents.

Understanding the interaction of HIPAA’s Privacy and Security Rules for the use of technology is critical for behavior analysts. The Privacy Rule protects PHI in “any form or media, whether electronic, paper, or oral” (US Department of HHS 2003). This means that remote supervision during a “live” or video recorded service session using videoconferencing software is subject to the Privacy Rule, as is the case for typical face-to-face discussion or a paper transcription of the session. For example, a provider would not use a client’s full name or date of birth during discussions with other practitioners in a public waiting area; thus, a provider cannot use a client’s full name during a video conference. Video or digital sessions, graphs/data in Excel™, etc., are no different and should be considered as “public” as a practitioner’s waiting area or a local restaurant. Therefore, avoiding the use of client names during the digital session can serve as one level of protection against a breach of the Privacy Rule. The best guiding principle for auditing one’s own behavior and practice is to remember that all electronically transmitted information that uses some form of Internet connection is by definition within the public domain. Even the use of certain “privacy” or “security” settings within a device will not necessarily protect the information from accessibility within the public domain.

The Security Rule, with its specific guidelines for electronic media, requires consideration of several components that are used to facilitate electronic transmission. To continue the example used above, the supervising behavior analyst and supervisee would need to confirm that the network hosting the videoconferencing software and any recording of the information (i.e., video file or PDFs) are encrypted and/or password protected. Even if a software application provides assurance of HIPAA compliance within their terms of use, an insecure or public network obviates any protection the software can provide. So, even if the supervisee and supervisor are using password-protected videoconferencing software and the supervisor is on a secure, encrypted agency Internet connection, a HIPAA violation could still occur if the supervisee uses the client’s home Wi-Fi (not encrypted) instead of logging in to a secure agency network through a password-protected account portal or website. This does not mean that using an “open” or nonsecure network automatically violates HIPAA; it merely means that one has to consider the type of information being transmitted and whether there is risk for breach. It is important to reiterate that the HIPAA Privacy and Security Rules outline different requirements of protecting client information. The Privacy Rule specifies the type of information that must be protected. The Security Rule describes the parameters for secure transmission of information in a particular form—electronic media. This does not imply that practitioners should not consider security measures for information related to client care that is in hard copy, oral, or other forms. In fact, extension of parameters specified in HIPAA for all client data will increase the likelihood of attaining high standards of care related to client privacy and confidentiality. Therefore, safeguards for access, transmission, and storage of client information are necessary.

Additional considerations are required for use of a mobile device with regard to electronic PHI (EPHI). Due to the increased use of mobile devices and their greater vulnerability to violations of the HIPAA Privacy and Security Rules, the US Department of Health and Human Services has issued several suggested risk management strategies and safeguard recommendations specific to EPHI, including password protecting all devices, applying automatic sign-off settings for specified periods of idle time on user accounts, or prohibiting off-site recording or transmission of information. Readers are referred to the US Department of Health and Human Services (2006) HIPAA Security Guidance website for additional information (http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/hipaa/administrative/securityrule/remoteuse.pdf). Also, enactment of the HIPAA Final Rule, based on provisions of the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act, further strengthens these protections and expands responsibility to business associates that receive PHI, including contractors and subcontractors (Modifications to the HIPAA Privacy, Security, Enforcement, and Breach Notification Rules under the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act and the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act 2013). Therefore, the billing agencies a service provider contracts with to manage insurance reimbursement, or other business associates involved in the ongoing transmission of PHI related to service provision, are held to the same standards of HIPAA compliance. An important revision to the definition of electronic media is contained in the final rule that specifies “…the physical movement of electronic media from place to place is not limited to magnetic tape, disk, or compact disk, so as to allow for future technological innovation…(and) transmission of information not in electronic form immediately before the transmission (e.g., paper or voice) is not covered by this definition” (pp. 11–12). Videos are clearly within the bounds of this clarification since the data exist in electronic form immediately upon recording. Any transmittal of the data is then governed by the expanded clarification of electronic media and physical movement. In this context, simply ‘playing’ a video file containing PHI is a form of transmission. It is important to note the Final Rule also sets penalties for violation to include fines starting at $50,000 per violation, with an annual maximum of $1,500,000. Importantly, a violation is referenced to an individual. Thus, if an agency had a violation wherein information about five clients was breached then that can be interpreted as five violations.

FERPA

Providers who work in educational settings may also be bound by the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act of 1974 (FERPA; 20 U.S.C. § 1232g; 34 CFR Part 99), also known as the Buckley Amendment. This federal law protects student records from release to unauthorized parties and permits students 18 years of age and older or their parents (until age 18) to access their student record if written permission is obtained. Release of information that would be considered PHI under HIPAA is permitted under FERPA, including a student’s name, address, telephone number, date and place of birth, honors and awards, and dates of attendance. However, schools are required to notify parents and students of their plan to disclose such “directory information” to allow adequate time for refusal (Family Policy Compliance Office n.d.).

FERPA does allow schools to disclose student records, without consent, to “school officials with legitimate educational interest, other schools to which a student is transferring, specified officials for audit or evaluation purposes, appropriate parties in connection with financial aid to a student, organizations conducting certain studies for or on behalf of the school, accrediting organizations, appropriate officials in the case of health and safety emergencies, and state and local authorities (within a juvenile justice system) pursuant to specific State Law.” Schools can also release student records to “comply with a judicial order or lawfully issued subpoena” (Refer to FERPA; 20 U.S.C. § 1232g; 34 CFR § 99.31).

An often overlooked aspect of FERPA is the situation in which a student, for example, an undergraduate, was participating in a course or volunteer activity and was videotaped in a university classroom setting as part of role-playing activities or as part of supervision activities in a practicum setting. In this instance, the video would be part of an educational record and FERPA rules apply. HIPAA rules would also apply in the latter case if the supervision activities involve client information. The specifics of the situation, nature of relationships, identifying information, and parties given access to the recordings all determine the nature and content of what consent documents must be obtained.

Regulatory Overlap

In November 2008, The US Department of Health and Human Services and the US Department of Education issued a joint publication to provide guidance on the integration of HIPAA and FERPA. Although the purpose of their publication was to clarify handling of student health records, this guidance document is a helpful guide for issues that arise in any setting that must adhere to both federal laws. For example, student records at health clinics run by postsecondary institutions are either “education records or treatment records under FERPA, both of which are excluded from coverage under the HIPAA Privacy Rule, even if the school is a HIPAA covered entity.” Further guidance is also provided for “hybrid entities” in which health records of nonstudents in postsecondary health clinics fall under HIPAA if the health care unit is established as a “health care component.” Any PHI maintained by other components of the university would be subject to FERPA only. Although an elaboration of case examples that fall under this overlap would be ideal, the complexity of such an analysis to cover all potential interactions is beyond the scope of the present manuscript. Agencies and providers who are governed by both HIPAA and FERPA are encouraged to assess their status and conduct a self-audit under the guidance of experienced compliance officers from both regulatory bodies. Readers are also referred to helpful resources available through the US Department of Health and Human Services website (http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/hipaa/administrative/securityrule/securityruleguidance.html) and the US Department of Education website (http://www2.ed.gov/policy/gen/guid/fpco/ferpa/index.html) to assess overlap in regulations that is beyond the scope of the present manuscript.

It is also desirable to appoint a compliance officer (CO) to be responsible for the processes, documentation and risk management practices, incident response plan, and current compliance requirements of the practice or organization. This individual serves a similar role for compliance as that recommended by Brodhead and Higbee (2012) regarding an ethics coordinator, who “functions as the resident expert of ethics by overseeing and monitoring individual and group supervision of ethical behavior” (pp. 84). Broadly, a CO is responsible for understanding the administrative, technical, physical, and organizational controls for each regulation. Administrative controls involve policies, procedures, standards, and guidelines that are typically set forth in organizational documents, while organizational controls focus on contracts and audit tools. Technical controls relate to the components of hardware, software, firmware, and related configurations, and physical controls are tied to locks, monitoring, and facility management (Bridgefront 2014).

Other Regulations

Although state and institutional regulations are also critically important in determining the best system or method for use, these regulations vary significantly across sites and state lines. Given this, a review of regulations at this level is beyond the scope of this manuscript. The authors will present an illustrative example that reflects some aspects of New York state regulations later in this manuscript; however, readers are directed to their own state governing body for information regarding specific regulations that affect their practice.

Video in Clinical Service Settings

The use of video for the purposes of treatment and supervision is not new to behavior analysts. Video has been used to teach clients to acquire specific skills and as a means to permit post hoc interobserver agreement ratings. Video is also commonly used for the purposes of supervision, particularly in situations in which live observation of trainees or staff is not feasible. In fact, the BACB recommends the use of web cameras, videotape, and videoconferencing in circumstances in which the supervisor cannot be physically present in the supervisory setting (BACB 2014). As the use of video in practice is multifaceted, the difficulties faced by organizations and practitioners are also multidimensional. It is not the case that statements such as “The client/guardian agreed to let me use their videos for …” are sufficient compliance measures. Further, reliance on popular commercial products (e.g., Citrix Online GoToMeeting®, Skype™, FaceTime®, DropBox, and various Google products (Google Hangouts, Google Drive) does not imply compliance with HIPAA, FERPA, or other standards for secure transmission of information. It is important to emphasize that “being HIPAA compliant” involves the entire process, not simply the hardware or software tool being used. The onus is on the user to appropriately understand the bounds and limitations in using such technology and the type of information and restrictions on the information being transmitted in order to be HIPAA compliant and also meet the aims of the project, client, or organization. While this can seem overwhelming, each agency or provider should assess the terms of use, security settings, and password protection options for each type of software under consideration for use. Further, all networks that are being considered for transmission of electronic PHI should be set up as secure, encrypted networks, combined with use of a firewall and virus-protection software. More discussion will be offered on this point later in the manuscript.

There is no “one size fits all” answer for the use, access, storage, and transfer of electronic files. The size and needs of the practice, agency, or institution are a central variable in setting effective policies and procedures to meet requirements and service needs. As noted earlier in this manuscript, HIPAA’s flexible parameters reflect this need. Although it is almost second nature for behavior analysts to seek operational definitions, clearly defined objectives, and task analyses to follow, regulatory bodies do not provide this level of detail in their laws and specifications and for good reason. In fact, many behavior analysts are likely quite aware of the impact of constraining laws given the limitations to the scope of practice that have occurred in some states with regard to licensure laws for behavior analysts. To demonstrate our point, imagine a law written such that all agencies were required to define and treat head-banging behavior in the same way. Clearly, most behavior analysts would see this as ridiculous since individualization is critical to the definition and treatment of individuals who exhibit challenging behavior. The implications of this become clearer if insurance reimbursement were only provided for services rendered to those who match the provided definitions or practitioners could be cited for not adhering explicitly to those requirements—starting with fines of $50,000. Federal, state, and institutional regulations regarding privacy and confidentiality are designed to avoid such a problem. The aim is to provide reasonable parameters and guidelines to allow sufficient individualization while providing some standard of practice with which to ensure client health information safety. If practitioners are unsure whether they are interpreting regulations correctly or if they have questions about whether their plans and equipment are sufficient to meet the reasonable and appropriate safeguards requirement, it is strongly recommended that they consult with other professionals. Consultation is always an appropriate step whether one is resolving a clinical or regulatory/legal issue. Professionals specifically in the legal and information technology (IT) fields can be invaluable in assisting practitioners with ensuring compliance and answering questions about potential data breach risks and implications of breach. Similarly, peers in the various helping professions can provide perspective and experience with respect to content and process issues.

Thus, it would be a disservice to provide a checklist or set of definitions as it would imply a consistency across situations and practitioners and would be antithetical to HIPAA guidelines in particular. Indeed, following a set ‘script’ of compliance procedures would itself be viewed as a negative in a compliance evaluation, as HIPAA is clear that an individualized process is required. The HIPAA Privacy Rule and the Security Rule provide standards of practice and describe principles rather than procedures. For example, the HIPAA Security Rule explicitly states:

HHS recognizes that covered entities range from the smallest provider to the largest, multistate health plan. Therefore, the Security Rule is flexible and scalable to allow covered entities to analyze their own needs and implement solutions appropriate for their specific environments. What is appropriate for a particular covered entity will depend on the nature of the covered entity’s business, as well as the covered entity’s size and resources.

Therefore, when a covered entity is deciding which security measures to use, the Rule does not dictate those measures but requires the covered entity to consider:

Its size, complexity, and capabilities;

Its technical, hardware, and software infrastructure;

The costs of security measures; and

The likelihood and possible impact of potential risks to EPHI.

Covered entities must review and modify their security measures to continue protecting EPHI in a changing environment.

(http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/hipaa/understanding/srsummary.html)

Demonstrative Example

To illustrate possible paths to secure the efficient use of digital records, we describe some of our work at the Institute for Child Development (ICD), located on the Binghamton University, State University of New York (SUNY) campus, which involves service delivery, teaching, and research. These programs and services are provided by a team of over 50 professional staff members as well as Binghamton University graduate and undergraduate students. Given the need to utilize resources efficiently in an environment with relatively few staff in proportion to the number, intensity, and diversity of programs, technology is frequently employed for clinical, research, supervision, and training purposes. Not surprisingly, data management across all programs and staff can be quite challenging, especially when considering the layers of regulatory requirements that are applied to various facets of the Institute.

Regulatory

To illustrate the potential complexity that can vary state-by-state, we offer the following analysis of the regulatory requirements that we had to address in the process of developing our organization’s policies and procedures. It is important to note that while the specific state regulatory requirements vary, the principles are highly similar and the aspect we wish to emphasize is the process, rather than the details, of addressing specific requirements.

While we are presenting one example of adherence to multiple regulations in the context of digital record security, we understand that not all practitioners and facilities will have access to the advanced technology highlighted in our examples. Therefore, we also provide several suggestions below to assist practitioners with developing procedures to meet compliance. Regardless of the suggestions provided below, each practitioner or agency is strongly encouraged to conduct a self-audit to assess level of compliance with all relevant regulations that govern their practice.

In addition to HIPAA and FERPA adherence, our programs are subject to policies and procedures of the New York State Education Department (NYSED), New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH), Binghamton University (SUNY), and the Research Foundation for SUNY. Each set of regulations specifies parameters for retention and disposition of records, as well as requirements for secure management and transmission. To avoid a lengthy review of all regulations, as well as reiteration of federal regulations already discussed, we instead provide systems specifications put forth by the New York State Division of Homeland Security and Emergency Services, Office of Cyber Security (soon to be subsumed under the Office of Information Technology Services) that align closely with HIPAA requirements and provide support for adhering to FERPA (New York State Office of Cyber Security 2010). The specifications to establish minimum levels of information security are summarized, in general, below:

Identify personnel to be responsible for the security of information.

Specify guidelines for accountability and confidentiality/integrity/availability including physical environment, equipment, and network security and encryption both on site and remotely.

Set security standards by classification of information and control access by those classifications (including personal, private, or sensitive information—PPSI—which should be classified as high confidentiality).

Set access control policies for physical and network access by level of employment, including privileged and administrator accounts.

Provide employee training and include security in job responsibilities.

Develop a plan for security incidents or malfunctions in the management process.

These minimum standards set an appropriate frame of reference to meet HIPAA and FERPA requirements for electronic record keeping privacy and security; however, the methods an agency or individual chooses to pursue to meet these standards will vary. Below, we provide our methods for meeting these standards and federal regulations for the purposes of video and electronic record keeping, storage, transition, and access. We encourage readers to use the above list as a starting point to outline the needs of the practice and determine strengths and weaknesses in each domain.

Personnel Controls

Access to this information, both physically and electronically, must be controlled in a manner that is easily maintainable and ensures adherence to policies. Information is classified both by its inherent level of privacy (i.e., public to highly sensitive information) and by the relevant program at ICD. Access to the physical facilities requires a valid keycard, issued only when an individual has completed the required training, signed the appropriate usage and confidentiality agreements, and has been cleared through the New York State Central Register Clearance System. Staff members are also required to complete an assessment of their knowledge for these security parameters as a condition of their employment. The same standard applies to undergraduate and graduate students participating in our programs and activities. While a valid keycard permits access to the physical facilities, only the most basic of information is accessible in common areas. Confidential materials are located in discrete zones by program(s), each with layers of increasingly limited keycard access. Equipment and networks to access video recordings, PHI, and similarly sensitive information are placed within specific restricted zones. Requests for authorization to access restricted areas are submitted through key supervisory personnel within each program, subject to final approval by program directors.

We recognize that not all physical facilities or storage locations used by other agencies or by individual practitioners will have the option to restrict access by keycard; however, any room, filing cabinet, or container that stores identifying client information does need to be locked for limited access. Locking file folders in a car trunk is not sufficient—a locked storage unit that is relatively impenetrable is required. Keys to these storage “units” should be provided only to staff that require access to complete service provision or reimbursement activities. For extra precautionary measures, a locked cabinet or container within a locked room is best. We strongly recommend that staff members in agencies be required to complete an assessment of their knowledge for security parameters as a condition of their employment. Further, agencies should identify an employee, and individual practitioners should identify themselves as a regulation compliance officer. The compliance officer is responsible for ensuring adherence to all regulations governing practice and should assess compliance knowledge and adherence at least annually for all employees.

Access

Electronic access to information resources at ICD, such as recorded training videos and organizational calendars, uses a similar hierarchy of control as that specified in the personnel controls section. Computer access accounts are created for personnel once they have undergone initial training and signed the appropriate usage and confidentiality agreements detailed above. These accounts initially have access to some training resources, but convey no access to private program resources like calendars, documents, or clinical videos. Much like the increasingly secure zones within the building, each electronic resource is associated with a program and level of privacy. For example, a newly hired special education teacher would have access to training videos and database software for the purposes of initial training, but would not have access to student records. In contrast, a newly hired senior clinical psychologist involved in evaluation and placement decisions would have access to training items plus student records and diagnostic reports and videos. Requests for access authorization are submitted to supervisory personnel for each designated program, subject to final approval by the program directors.

For other agencies and practitioners, all devices, both mobile and nonmobile, should be password protected and set to log out of the user account after a specified period of “idle” time. Any storage methods (e.g., CDs, external hard drives, flash drives) or devices stored within the storage units should also be password protected. The username and password for devices and accounts should be different than those set for storage methods. However, it is also necessary that all staff be trained to maintain their usernames and passwords and that they are responsible for any activity performed under their account; therefore, sharing of usernames and passwords is inappropriate and can be grounds for termination of employment due to the risk to clients. Further, password changes should be required at a specified interval, at least on a quarterly basis, and staff should be trained not to store their usernames and passwords in a visible location by their work area. These safeguards ensure that there are multiple levels of access that must be passed to obtain client information. Staff should also be discouraged from using their personal devices for professional purposes in order to reduce the likelihood that lines will blur between personal and professional access to information.

Storage

Failure to plan for digital and physical storage can result in efficiency losses when trying to find the right file or reintegrate multiple copies of separately edited files. Data losses are also a concern when storage capacity is unexpectedly reached. More importantly, disordered storage impairs the ability to maintain accountability and integrity for information classifications and can result in unauthorized materials being placed into locations without the appropriate security. Each program at ICD has its own secure file location on a server (a specialized computer with software that communicates with and provides data to other designated computers), with increasingly restricted clearly labeled sub-folders. Each program has a single supervisory contact person responsible for reviewing the content to ensure it is stored appropriately.

As mentioned in the introduction, storing voluminous records is easily achievable using low-cost devices, many of which are portable. A $25 USB flash drive can store 90 diagnostic reports and many hours of video, while a typical laptop computer could store thousands of reports and a hundred hours of video. The problem with these increased storage options is that it easily permits individuals to keep confidential records on mobile devices, resulting in very high and unacceptable risks. Policy dictates all information recorded to mobile devices be transferred by the end of the day to the appropriate server location then immediately purged from the recording device.

In terms of storage for other agencies or individual practitioners, best practice would entail the requirement that all staff transfer digital files and information from any individually assigned devices to a centralized storage system that is encrypted and behind firewall protections. Password-protected mobile devices can be used to store video or digital information until the provider has returned to the practice site, at which point the data and files can be uploaded via USB or some other wired connection. Readers are strongly encouraged to require all transfer of digital information to a secure storage system by the end of each business day, with subsequent deletion of that information from the mobile or personally assigned nonmobile device. When files are stored, a specified indexing strategy should be used so that files are organized and easy to locate, with no identifiable information included in the indexing filename. Data should also be backed up regularly to avoid corruption and delays in recovering information needed to sustain client care.

Transmission

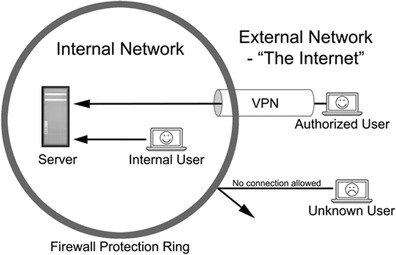

It is not commonly understood that when information is sent between two computers over the Internet, that information is actually routed through many different electronic devices, which are virtually impossible for the typical user to fully identify and trust. This might include passage through unknown networks or intermediary sites. Internally, ICD operates an internal switched network—a ‘locked’ system. This means that information transferred between two computers or a computer and our server never leaves the building and therefore never passes through a piece of equipment we do not own. This network is also protected by a security feature, known as a “firewall,” which prevents access by unauthorized external computers. This can be described as a protective “ring” that is often composed of hardware and software components. Computers and devices are also highly restricted with respect to Internet access. Individual users who require external access must provide a justification and receive approval. Such access is controlled via a central software system that is part of our internal network.

Approved staff who wish to access the closed network offsite must take the extra step of connecting to a virtual private network (VPN), which is an industry standard method of securing all communication between a user computer and a server through encryption. This is necessary because the information will pass through untrusted networks (as mentioned previously) as it travels between the trusted user and server. For example, a practitioner or researcher conducting an observation in a community setting might need to access an electronic client or participant record to enter notes or record data. To accomplish this with appropriate safeguards, a specialized URL (uniform resource locator) link can be provided that prompts the user to use a login name and password to allow entrance to an approved VPN. The user can then access and transmit information through a secure, protected link from the external location. See Fig. 1 for a diagram of VPN access.

Fig. 1.

User communication with an internal server across internal and external networks with the use of a virtual private network (VPN)

While protecting information from unauthorized external access is important, it only solves part of the problem. In the VPN example above, it is important to note that only the information sent from the external user to the internal server is protected. The VPN will not protect information stored in a “cloud” service, such as Apple’s iCloud. Also critical is reducing leakage of information by authorized users. Unauthorized information sharing can be a result of improper, albeit not always intentional, access of websites that risk the security of the server or by external agents seeking to siphon information from users.

The first layer of protection against such information leakage consists of restrictions. This typically involves software running on servers, the network, and individual user’s computers that prevent one or more types of dangerous activity. For example, Microsoft Windows Group Policy and Apple’s Profile Manager specify a variety of settings for computers limiting everything from access to specific websites to the ability to connect USB drives to a computer. Information technology or network administrators can usually assist with enabling these tools, which will operate without requiring any action by the protected user.

The second layer of protection involves training users how to practice safe computing habits, like how to identify fake ‘phishing’ email messages. External efforts to trick authorized users into accidently revealing information, such as passwords or important account information, often take automated protections used as a first line of defense into account. Therefore, staff training regarding safe computing and identification of potential security risks and breaches, as well as subsequent reporting to the appropriate administrators selected for security monitoring, is as important as software, hardware, and network security.

Finally, a practice of routine monitoring must take place to identify the ongoing effectiveness of the “automated” tools and staff training. During this process, the implementation of the tools and the content of the training may be updated to address new threats (i.e., Heartbleed bug, ILOVEYOU, or Klez viruses) or review detected lapses in policy.

For other agencies and individual practitioners, perhaps the easiest recommendation for secure transmission is to prohibit recording or communication of client information from any off-site location. While easiest, this is hardly conducive to the broadening service delivery needs of behavior analysis consumers. If transmission of data must occur while a provider is off-site, it is strongly recommended that a secure network be established that requires a user to log in to the system with a username and password. The secure network will need to be encrypted, not just password protected, so it is critical that practitioners consult with information technology specialists to ensure the system is set up correctly if they are unable to complete this assessment on their own. Once on the secure network, files can be delivered to a centralized, secure location and then immediately deleted from the mobile device. In the event of live streaming, the encrypted network can serve as protection for the incoming data. If practitioners cannot set up or access a secure network, data should not be transferred wirelessly or via the Internet.

Application and Process

Our guidelines and procedures apply to all forms of electronic information, be it email, documents, shared calendars, or any other of a growing list of ways we store and disseminate information at ICD. The specific example we use to demonstrate is video recording, but the practices applied are not limited to that example.

As previously mentioned, video media can be used for a variety of purposes, sometimes with overlap between purposes. This presents challenges of storage, transmission, and access, each with their own security and privacy concerns. Storage encompasses not only the need to protect data “at rest” but also the need to organize information to facilitate retrieval and enforce clear access control. Transmission of information must ensure that privacy and security are protected during transit. Finally, access addresses the need to enforce strong access control while permitting availability to authorized users without undue effort. All too often, due to not fully understanding the scope and specifics of the relevant issues, “solutions” are imposed on staff that render systems almost unusable and inadvertently encourage staff to find ways to bypass security measures. In our case, the administrative, clinical, research, and information technology staff worked as a single team, learning each other’s language so to speak, in order to prevent developing a system that would be too cumbersome to effectively use.

In order to address these many different categories of concerns, we very carefully chose core software components to form a secure system. We chose the database software FileMaker™ because of its strong security and ability to manage many levels of access as well as its facility for application across handheld devices, smartphones, laptop/desktops, and web-based access.2 Video is often recorded using an Apple iPad™ preset to require the use of a passcode for basic access control and encrypts stored files when a passcode is set. Video can also be recorded using a designated laptop or video camera. Videos are then transferred, as described later, bringing it within the full system of access control in FileMaker™ and the full protection of our network. This database software utilizes password-protected user accounts to implement access control. Additionally, it facilitates creation and maintenance of organized file storage that is encrypted to prevent access by unauthorized users. In other words, when users access the FileMaker™ server, the information between the user computer and the server is encrypted to prevent “eavesdropping.” By policy, once a video file is safely stored within the FileMaker™ server, it is removed from all other locations not only to ensure privacy and security but also to limit redundancy. The served file is then securely accessible by authorized users.

Within our solution using FileMaker™, files are automatically time coded and indexed under multiple methods of categorization to aid in retrieval. By default, the most current version of a file is accessed when sought, but its historical versions are maintained. The files stored on the server are protected by Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) encryption, an industry standard method of protecting files from being readable without authorization.

The initial transfer from a recording device to server is done via a simple ‘sync’ cable at a dedicated, password-protected workstation. This ensures that the transmission to the server is done securely and that the information about the file is entered immediately upon storage to allow proper organization and access control to be applied. As mentioned previously, most information accessed from FileMaker™ is automatically protected with encryption for transmission. Nevertheless, we take the additional step of utilizing a virtual private network (VPN), which ensures all communications are protected by an additional layer of encryption. We chose to use the VPN function built in to Apple OS X server as well as Apple desktop and laptop computers, for the simplicity of implementation, ease of use, and cost.

Once categorized into the database, files can be made available based on their individual privacy and security requirements. In some cases, users access the videos from the server using a secure website on the internal network, which cannot be viewed outside the building. This format allows staff and students to have access to necessary training videos and other video media on demand while inside the building. External access using the VPN from off-site is not permitted for video media with identifiable images of children enrolled; however, recorded didactic training videos with slides can be provided on- and off-site with ease.

The purpose of our outline above is to describe the rationale for choosing the hardware and software platforms that we presently use. We acknowledge that there are a variety of Windows and Mac products available to consumers, and it is in the agency’s or individual’s best interests to pursue those technology solutions that best meet their current needs. As stated earlier in this manuscript, we strongly recommend consultation with legal and information technology (IT) professionals to establish a system that best aligns with the individualized needs of each practice.

Indexing

Once all privacy and security parameters have been addressed, consistent file naming has critical implications for searching and accessing video files, as well as maintaining management of those files. The rationale for using a consistent naming convention is centered on the principle of organization. For example, one might organize paper-based client files in a specified manner, say by client name or by a specific identification code. Video files that are stored electronically require the same careful consideration in order to facilitate more effective use, storage, and access to this important data history.

A good standard for indexing that has served our program needs well is to designate each file by relevant person or audience, event, and date. This method provides for consistent, accessible search terms that can be written into procedural guidelines. Below are several examples of what this might look like, taking into consideration protection of PHI with regard to clinical files:

- Clinical files

- JDil_PreschoolEval_09-25-13

- JBie_FunctionalAnalysis_10-15-13

- Training files

- Inservice_IncidentalTeaching_01-01-13

- UndergraduatePrep_ABAIntro_09-01-13

While this type of initial organization is useful, it is only functional if new versions of the same form are saved with the date of modification so that all parties are working from the most recent draft. It is recommended that the use of words such as “current” or “draft” or “final” in the file name not be used as they can be misleading and often detrimental to collaborative work efforts. Such names have meaning to the user at the moment, but are not useful within a shared access model. As is the case with effective science, maintaining simplicity and precision in wording will improve understanding, communication, and use.

Analysis

Video recordings are produced for clinical, research, supervision, and training needs at ICD. Once videos are recorded, stored, and indexed accordingly, the next step is analysis of the video recordings. The type of analysis varies given the initial purpose of the video recording. As an example, videos produced for a research study on functional analysis are analyzed in a secure room with access only allowed by individuals approved by the Human Subjects IRB for that study (e.g., research assistants). The videos are stored on a research server that is password protected and has the same level of limited access (i.e., for those listed on the approved study protocol). These video recordings are often uploaded to behavioral scoring software programs or apps, which exist on the computers in the secured research area. It is imperative that these apps and software programs do not “store” the videos on a server elsewhere (e.g., the “cloud”). Equally important is that the data obtained from the behavioral observation software/app is exported to the secured desktop and are not saved in such a way that would allow access by others not approved for the research study. When performing data analyses, it is of equal importance to have the file names (e.g., Excel™, SPSS™, etc.) indexed appropriately and that these files are stored appropriately as well.

Videos contain a wealth of behavioral data that can serve multiple purposes, and at times, the videos recorded are not intended to “stand alone.” That is, certain video files can interact with other technology (e.g., apps or software programs). One such example is in the domain of supervision. Ongoing staff and student (undergraduate or graduate) supervision is key to maintaining procedural integrity, accurate data collection, and professional behavior (Reid and Parsons 2006). To assist with supervision, an “in-house app” was developed and is used daily by multiple supervisors. On average, 50 supervision sessions are conducted on a weekly basis. The supervision app allows supervisors to easily record staff/student behavior, enter written comments, and when needed, collect a video sample. While the video sample might have been collected for the purpose of supervision, because of its integration into a database system, a variety of other uses are possible (with proper permission process), for example, to identify a repeated data collection error or to capture the antecedents and consequences of problem behavior that may need to be the focus of a functional analysis. These ad hoc video samples can then be viewed in a broader context by designated clinical staff to make better and more informed clinical decisions. Similarly, exemplary supervision videos might be used for developing training videos.

Additional Recommendations

Unfortunately, we cannot provide an exhaustive guide for practitioners to become regulation compliant because compliance is a process, not simply a checklist. Nevertheless, there are some specific steps that are important to the process. According to HIPAA.com (HIPAA, LLC 2014), there are five specific steps that practitioners should follow to assess their level of compliance. While these steps are specific to HIPAA, readers will see the steps are clearly generalizable to other regulations. In order to better explain these steps, some comment (in italics) is offered on how practitioners might achieve each step.

- Conduct a complete risk assessment

- Outline the specific requirements of each regulation, assess the existing practice for complete compliance with each aspect of the regulation, and assess areas of weakness and obsolete systems to be repaired or removed.

- Prepare for disaster before it happens

- Be proactive and identify the steps and personnel that will be involved if a breach occurs at any level of security.

- Assess and update safeguards in place as often as feasible for your practice, but at least annually, even if no breaches have yet occurred.

- Maintain an ongoing employee training program

- Provide employees with written manuals outlining compliance procedures, provide didactic instruction and knowledge assessment on implementation of those procedures, and perform regular compliance checks during regular work activities.

- Buy products and services with compliance and regulation compatibility in mind.

- Conduct research on the reviews and security assessment of products you wish to use in your practice; just because something is new and promises secure settings does not mean it is regulation compliant. Look for keywords citing actual regulations relevant to your practice in product information or request documentation of such from the vendor.

- If this level of assessment is beyond your ability or the products cannot provide that level of protection, consult with an information technology specialist or agency to provide you with support.

- Collaborate with other affected providers, practices, or business associates.

- Your colleagues and service providers in related fields who have already undergone compliance processes and audits will be the best resources for developing effective policies and procedures for compliance implementation and ongoing review in your practice.

- Step outside of your field and reach out to other professionals in the health community who can advise you on the successes and pitfalls they have encountered.

Positive Impact as a Function of Having a Compliance Focus

One of the clear implications of having well-organized digital records, with accompanying procedural and policy structures in place, is that questions can be asked that are not possible with traditional research and clinical ‘files.’ While not at the level of so called ‘Big Data’ concepts, which would apply to efforts aggregating the type of data described here over, for instance, all autism service providers who utilize ABA methodology, the possibility of aggregating diverse information within an organization or group is nevertheless desirable.

While some procedures we implement greatly enhance staff efficiency, we must guard against regulatory compliance procedures that reduce staff efficiency by carefully evaluating the procedures we impose and comparing alternatives. It is critical that such procedures are not burdensome to staff such that it could decrease their likelihood of compliance due to the “extra work” involved. Thus, procedures and devices must be easy to use, and systems such as encryption and VPN connection must be ‘transparent’ to the user so that no effort or specialized skill is required.

Summary

It is simply a myth that appropriate solutions are very expensive and difficult to maintain. It is true that while there are indeed approaches that are expensive and difficult, they do not necessarily provide better compliance. All costs incurred to assess and implement compliance procedures must be considered in parallel with the needs of the individual or organization from a systems efficiency, information security, and clinical impact standpoint. Although an initial analysis of procedures, equipment, and security needs is time consuming, ensuring the correct resources are in place will allow for a long-term reduction in resources allocated to management and recovery from security breach and data loss. Violations of HIPAA, FERPA, and other regulations at state and institutional levels occur most often from failure to plan effectively to protect against data breach, not just the data breach itself. Proactive investigation to set parameters to support secure use, storage, transmission, access, and analysis of digital records can be an invaluable tool for behavior analysts. When soliciting specifications for solutions particular to one’s own needs, the behavior analyst’s expertise in formulating operational definitions should be brought to bear along with a basic understanding of the processes we have described.

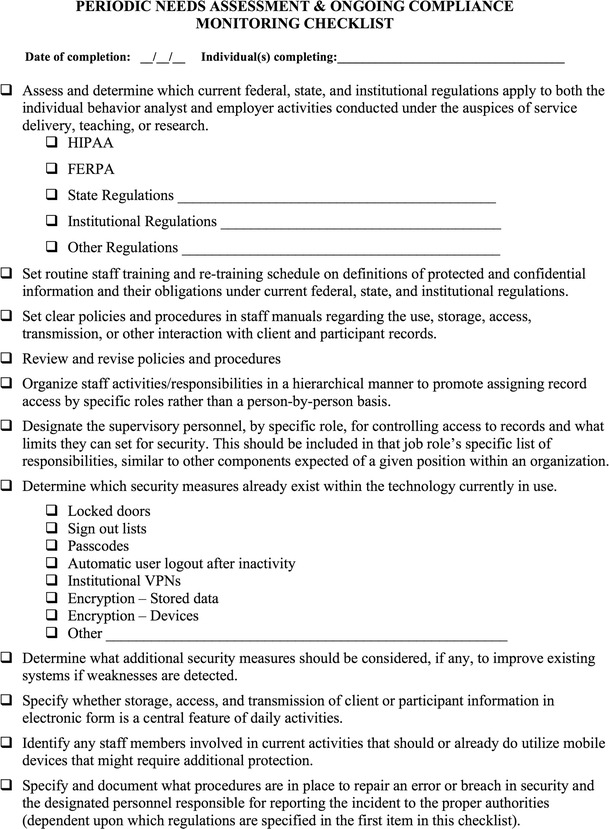

In summary, behavior analysts in all settings must consider multiple issues as a starting point during needs assessments for the use of technology in the storage, access, transmission, and analysis of client information. Readers are referred to Fig. 2 for a basic checklist we have compiled to illustrate and assist with decision-making for assessing and monitoring security and compliance. However, there cannot be a ‘definitive’ checklist or process, as HIPAA requires that organizations use an idiographic approach of ‘self-study’ on a repeating basis, rather than follow a specific, explicit set of rules. The use of this and similar checklists and other compliance and monitoring procedures must be part of an ongoing process, with specified review dates written into individual provider or organizational policies and procedures.

Fig. 2.

Periodic needs assessment and ongoing compliance monitoring checklist

As insurance reimbursement and third party management systems and software become more integrated with standards of care and continued evolution of standards for storage, access, and collection of information about research participants occurs, the need for adherence to federal, state, and institutional regulations will become the norm. Therefore, the ability of behavior analysts to readily meet the necessary specifications for secure and ethical use of electronic media and data becomes central to research, teaching, and practice, and the integrity of the field.

Acknowledgments

In memoriam: Nathan Kruser (July 1976–October 2014)—ICD Information Systems Coordinator, colleague, and friend

Glossary

- Cloud (“cloud computing”)

Computer network connected to a computer or group of linked computers (server) that allows the hardware and software demands to be removed from the local machine and handled by the cloud computer network; most email accounts are set up using cloud computing

- Database

An organized collection of data, often supported by a specific type of software (i.e., Excel™, FileMaker™)

- Data loss

An error condition in which stored digital information is destroyed by failures or neglect in storage, transmission, or processing. Backup and disaster recovery equipment can prevent data loss

- Data transmission

Any transfer of data in either physical or digital form, including transmission of keystrokes on a keyboard to a computer screen, a phone call, or a video signal

- Digital storage

Hard drives and other storage devices that hold and/or process digital information for storage and retrieval; these devices may be stationary, such as on a computer desktop, or portable/mobile

- Encryption

The process of encoding messages or information in such a way that only authorized parties can read it; it does not prevent a message from being intercepted, but it will prevent the content from being read (Advanced Encryption Standard or AES is a specification for the encryption of electronic data established by the US National Institute of Standards and Technology—NIST—in 2001)

- FileMaker™

A software application to develop databases that is a subsidiary of Apple

- Firewall

A software or hardware-based network security system that controls the incoming and outgoing network traffic. Firewalls establish a barrier between a trusted, secure internal network and another network that is assumed to be insecure or untrusted

- Heartbleed bug

A security bug that attacked secure webservers that allows information to be stolen using the encryption typically used to secure the Internet and allows anyone on the Internet to read the memory of the systems protected by the vulnerable versions of the OpenSSL software

- ILOVEYOU virus

An email-driven virus with “I LOVE YOU” in the subject line that contains an attachment that, when opened, sends the message to everyone in the recipient’s Microsoft Outlook address book and wipes every JPEG, MP3, and certain other files from the recipient’s computer

- Intermediary network devices

Devices that provide connectivity and work behind the scenes to ensure that data flows across the network, including routers, switches, hubs, wireless access points, servers and modems, and security devices

- Klez virus

A virus transmitted through email that replicates itself and sends to all those in the victim’s address book; it often contains other harmful programs that can disable virus-scanning software or the full computer’s functionality

- Mobile device

Any computer, tablet, cell phone, video camera, DVD or tape recorder, or other portable devices capable of storing electronic or digital media for any length of time

- Network

A telecommunications system that allows computers to exchange data. Networks can be internal (private network within an organization) or external (public); internal networks do not guarantee the safe transmission of digital information without appropriate safeguards

- “Phishing”

The attempt, usually by an unknown or unfamiliar entity, to acquire sensitive information such as usernames, passwords, and other account information by pretending to be a trustworthy source; email communications used for phishing typically have weblinks, which can be infected with viruses or malware (malicious software)

- Restricted folder/subfolder

File storage location on a computer or mobile device in which a username and password or other access restriction is applied so that contents are “locked” unless special authorization is given

- Server

A specialized computer or group of computers with software that communicates with and provides data to other designated computers

- Uniform resource locator (URL)

A web address

- Virtual private network (VPN)

A VPN extends a private, internal network across a public network and enables a computer to send and receive data public networks as if it is directly connected to the private network (i.e., secure)

Footnotes

Applicable regulation and law vary from nation to nation, and a review of such variation is beyond the scope of this paper. Thus the US is used in the context of an example to illustrate the complexity of interacting elements. The process we illustrate of compliance is thus applicable to all jurisdictions.

For more information about our comprehensive use of this database development software see http://www.filemaker.com/solutions/customers/stories/155.html

References

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board (2010). Guidelines for responsible conduct for behavior analysts. Retrieved from http://www.bacb.com/Downloadfiles/BACBguidelines/BACB_Conduct_Guidelines.pdf

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board (2014) Behavior analyst certification board: experience standards. Retrieved from http://www.bacb.com/Downloadfiles/ExamApplications/bcba/experience%20standards.pdf

- Bridgefront (2014). What is a compliance officer? Retrieved from http://www.hipaabusinessassociates.com/compliance_officer.php

- Brodhead MT, Higbee TS. Teaching and maintaining ethical behavior in a professional organization. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2012;5(2):82–88. doi: 10.1007/BF03391827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act, Pub. L. 93–380, 34 CFR Part 99, codified at 20 U.S.C. § 1232g

- Family Policy Compliance Office (FPCO). (n.d.) Family educational rights and privacy act (FERPA). Retrieved from http://www.ed.gov/policy/gen/guid/fpco/ferpa/index.html

- File, T. (2013). Computer and internet use in the United States: population characteristics. U. S. Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration; U. S. Census Bureau.

- Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act, Pub. L. 112–164, 123 Stat. 115, codified as amended at 42 U.S.C. § 201.

- Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, Pub. L. 104–191, 100 Stat. 2548, codified as amended at 42 U.S.C. § 201.

- HIPAA, LLC. (2014). Five steps to HIPAA security compliance. Retrieved from: http://www.hipaa.com/2013/10/five-steps-to-hipaa-security-compliance/.

- Modifications to the HIPAA Privacy, Security, Enforcement, and Breach Notification Rules under the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act and the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act; HHS Office of the Secretary, 78 Fed. Reg. (January 25, 2013) (to be codified at 45 C. F. R. pts. 160 & 164). [PubMed]

- New York State Office of Cyber Security (2010). Cyber security policy P03-002: information security policy. Retrieved from http://www.dhses.ny.gov/ocs/resources/documents/Cyber-Security-Policy-P03-002-V3.4.pdf

- Reid DH, Parsons MB. Motivating human service staff: supervisory strategies for maximizing work effort and work enjoyment. (Vol. 3) Morganton: Habilitative Management Consultants, Inc.; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rogowsky, M. (2013). More than half of us have smartphones, giving Apple and Google much to smile about. Forbes – retrieved 1/10/14 from http://www.forbes.com/sites/markrogowsky/2013/06/06/more-than-half-of-us-have-smartphones-giving-apple-and-google-much-to-smile-about/

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2006). HIPAA security guidance. Retrieved from http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/hipaa/administrative/securityrule/remoteuse.pdf

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office for Civil Rights (2003). OCR privacy brief: summary of the HIPAA privacy rule. Retrieved from http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/hipaa/understanding/summary/privacysummary.pdf

- Whiting SW, Dixon MR. Creating an iPhone application for collecting continuous ABC data. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2012;45(3):643–656. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2012.45-643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]